1

Controlling Bureaucracies

We live in a democracy. That fact, taught in school and persistently reinforced by political oratory, is a source of pride and satisfaction to most of us. Although we often disagree about what a democracy entails, most people would probably accept the idea that the heart of a democratic political system is control of the government by the governed. In modern, complex democracies complete control is, of course, impossible, but at minimum we expect the popular election of public officials.[1] Americans are particularly fond of using elections to keep public officials accountable. While the turnout for American elections is smaller than in many democracies, the number of officials we elect is large.

We also live in an increasingly bureaucratized society. Large organizations—corporations, unions, merchandising chains—play a growing role in our lives. So, too, do large government agencies. Almost one-fifth of working people in this country are government employees, and in spite of our propensity for elections, only a tiny fraction

[1] Robert A. Dahl, Dilemmas of Pluralist Democracy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982).

of these are elected officials.[2] The public official a citizen is most likely to encounter is not a legislator, mayor, governor, or president, but a bureaucrat—an IRS agent, an administrator in the motor vehicles bureau, a welfare worker, or an agricultural extension agent.

As almost anyone can testify, these bureaucrats do much more than the proverbial paper pushing. They routinely make decisions that significantly affect the way government serves or regulates its citizens. Congress may pass the tax code, but an IRS agent decides whether a specific individual's expenses qualify as deductions. A state legislature may enact a program designed to improve the basic skills of students, but state administrators decide which particular programs and which particular schools are eligible for funds. A city council may pass a rent control ordinance, but local bureaucrats decide whether the improvements an individual landlord has made mean that rents for individual tenants may be raised. Although the impact of each of these decisions may be small, collectively they determine the texture of the relationship between citizens and government.[3]

Bureaucrats have not usurped this power from elected officials; they have been given it deliberately. Congress would be crippled if it had to decide on each citizen's taxes, as would city councils if they had to assess all rents. State legislators rarely have the expertise to evaluate individual educational programs. Elected officials have neither

[2] U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States 1982–3 (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1982), p. 394.

[3] Michael Lipsky argues that "there are many contexts in which the latitude of those charged with carrying out policy is so substantial that studies of implementation should be turned on their heads. In these cases policy is effectively 'made' by the people who implement it." (Lipsky, "Standing the Study of Public Policy Implementation on Its Head," in Walter Dean Burnham and Martha Wagner Weinberg, eds., American Politics and Public Policy [Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1978], p. 397).

the time nor the specialized competence to make such decisions. These officials choose to delegate power to bureaucrats both for reasons of efficiency and to take advantage of the professional competence many bureaucrats possess.

Yet the result of such delegation is that the people making the myriad decisions about who benefits and who is regulated are not voted in and out of office by the citizens they are benefiting and regulating. They are generally people hired on the basis of competitive examinations, promoted on the basis of the judgments of other bureaucrats, and fired only under extreme provocation. How then is their work to be controlled by ordinary people? How can we reconcile the growth of decision making in powerful government bureaucracies with our ideas of democracy and popular control?

Current political debate testifies to the seriousness with which some view the problem. A central question in many political campaigns has been which candidate can best grapple with the bureaucracy. Over a decade ago an unsuccessful presidential aspirant mobilized his supporters by decrying bureaucrats in Washington who carried nothing more in their attaché cases than their lunches. More recently, presidential candidates have waged successful campaigns running as Washington outsiders unbeholden to entrenched bureaucratic interests and therefore allegedly better able to control them. Once in office most successful candidates have discovered that the problem is more formidable than they thought. Merely announcing a change in marching orders is rarely enough to shift markedly the direction of the tens of thousands of bureaucrats who control the day-to-day operation of government agencies and who possess both the information and the expertise necessary to make those agencies work.

The need to control bureaucracies is a problem that

crosses many political boundaries. Officials trying to cut back the scope of government activity can find themselves frustrated by bureaucratic inertia, as happened to the Nixon administration in its efforts to reduce public welfare expenditures. High-level officials found themselves unable to stem burgeoning spending because bureaucrats in the then Department of Health, Education, and Welfare were unwilling to monitor and limit the activities of the state and county officials whose programs were fueling the budgetary fires through federal matching provisions.[4] Leaders who seek to expand or change the scope of government action can find themselves equally frustrated. For example, when the New York City Board of Education sought to increase integration through policies such as open enrollment and comprehensive high schools, it was hindered by the refusal of bureaucrats to disseminate information about the options to parents and to design new curricula.[5]

Neither is the problem of governing bureaucracies limited to the United States. Ezra Suleiman describes the French bureaucracy as "accused of technocratic power and arrogance, of bureaucratic highhandedness and inefficiency … and of constituting a closed and a ruling class."[6] In Great Britain Michael Gordon finds civil servants whose influence "is hardly confined to an administrative exercise" and who "may even determine the ultimate success of the party's program."[7] Throughout the Western world elected officials find themselves dependent

[4] Richard P. Nathan, The Plot That Failed (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1975),p. 84.

[5] David Rogers, 110 Livingston Street (New York: Random House, Vintage Books, 1968), chap. 8.

[6] Ezra N. Suleiman, Politics, Power and Bureaucracy in France (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974), pp. 30–31.

[7] Michael R. Gordon, "Civil Servants, Politicians, and Parties," Comparative Politics 4 (1971): 41–42.

upon appointed ones to achieve their political ends. The challenge for these officials is to find sensitive and nuanced ways to control bureaucrats without losing the benefits that bureaucratic action brings.

Control of large bureaucratic organizations is not a problem unique to democratic political systems. Leaders of large corporations and heads of nondemocratic nations also find themselves confronting bureaucrats who are not always pliable. Corporate leaders, for example, may find their efforts to computerize company finances thwarted by the persistence of an accounting department in conducting its business by hand. Military governors trying to change the regional distribution of public services may be no more able to alter established bureaucratic patterns than their democratically elected counterparts.

Controlling bureaucracies, however, takes on special urgency in democracies because unaccountable power flies in the face of the central norms of such political systems. When the legitimacy of a government derives from the consent of the governed, the problem becomes not merely an inability to get the governmental apparatus to act in ways the leaders or citizens wish but also a challenge to the fundamental nature of that government.

Early analysts of administration did not see the reconciliation of democracy and bureaucracy as a problem. They accepted, at least in principle, the Weberian description of the impersonal bureaucrat working with equal diligence for a succession of masters.[8] Writers such as Frank Goodnow and Woodrow Wilson believed that the administrative realm of the bureaucrat could be separated from the political or policy-making functions of legislators and

[8] H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills, From Max Weber (New York: Oxford University Press, 1946), pp. 228–29.

elected executives.[9] Democratic control of appointed administrators was assured through their subservience to elected officials.

Of course, such a neat compartmentalization of government functions is illusory. A dichotomy between policy and administration may be a comfort to those fearful of bureaucracy's undemocratic features, but it is not an accurate description of reality. In the course of making their decisions about how a program will actually work, bureaucrats give that program shape and form. They are guided by the decisions of legislatures, but those decisions often do little more than establish a broad domain within which bureaucrats must act. Carl Friedrich summarized this less tidy view by asserting, "Public policy, to put it flatly, is a continuous process, the formulation of which is inseparable from its execution."[10]

More recently, scholars have explicitly compared bureaucrats and politicians in terms of their political beliefs and their contributions to the policy process. They have found that though the process may be continuous, these two sets of political actors do play different roles.[11] The resurrected distinction between bureaucrats and politicians is not, however, one in which the former passively serve the latter. Rather it is one in which politicians and bureaucrats bring distinctive perspectives and competencies to policy making.

[9] Frank J. Goodnow, Politics and Administration (New York: Macmillan, 1900), and Woodrow Wilson, "The Study of Administration," Political Science Quarterly 56 (1941): 481–506.

[10] Carl J. Friedrich, "Public Policy and the Nature of Administrative Responsibility," in C. J. Friedrich and Edward Mason, Public Policy 1940 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1940), p. 6.

[11] Joel D. Aberbach, Robert D. Putnam, and Bert A. Rockman, Bureaucrats and Politicians in Western Democracies (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1981).

The problem of control thus remains, and the question recurs, What methods can be used to govern policy makers in public bureaucracies democratically? The early architects of our political system, although greatly concerned with avoiding tyranny, gave little thought to the problem. As Peter Blau explains, "Our democratic institutions originated at a time when bureaucracies were in a rudimentary stage and hence are not designed to cope with their control. To extend these institutions by developing democratic methods for governing bureaucracies is, perhaps, the crucial problem of our age."[12] Unfortunately, it is a problem for which there is no single solution.

Perhaps because our political institutions were not designed at a time when large, powerful bureaucracies were prevalent, efforts to control them have been varied, but not systematic. The Constitution makes little mention of the bureaucracy; its only requirement is that the president appoint the heads of the executive departments with the advice and consent of the Senate. Our federal system of government has allowed the individual states to experiment with their own modes of controlling bureaucracy. Political executives, legislative oversight, administrative courts, advisory boards, review boards, ombudsmen, ethics legislation, community control, "sunshine" laws, and many other tactics have been touted and tried as means of control. But the choice of a specific control mechanism often seems to depend more on political fads than on careful assessment of the relative merits of various possibilities. Debate over methods, in both the political and the scholarly arena, generally has an ad hoc quality, with the focus on the effectiveness of specific procedures, not

[12] Peter M. Blau, The Dynamics of Bureaucracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963), p. 265.

on how diverse control mechanisms affect the overall problem of reconciling bureaucracy and democracy.

The language used to discuss democratic control complicates efforts at more general appraisal because that language is capable of many interpretations. Everyone, for example, wants a "responsive" school bureaucracy, but what they want may vary considerably. For parents it may mean administrators who consult them on curricular issues, for teachers it may mean a system that applies due process criteria to all personnel decisions, and for the mayor it may mean a superintendent who coordinates school policies with those of other city agencies.

Such ambiguity hides substantially different analyses of the problem of bureaucratic control. As James Q. Wilson has noted, "There is not one bureaucracy problem, there are several, and the solution to each is in some degree incompatible with the solution to every other."[13] For the parents in the example above, the bureaucracy problem lies in the procedures school administrators use to reach decisions. For the teachers, the problem lies in the capriciousness of the results of decision making. And for the mayor, the problem lies in the fragmentation of bureaucratic decision making. Each actor sees controlling bureaucracies as a way of achieving a different political value, and each actor would go about pursuing control in a somewhat different fashion.

Access, fairness, coordination, and many other goals are all desirable for a democratically controlled bureaucracy, but they are by no means the same, nor always compatible. Reforms aimed at realizing one value may impair our ability to realize others. An agency that treats all citizens identically is not likely to be one that responds flexibly to variations in citizen needs. Communities that introduce

[13] James Q. Wilson, "The Bureaucracy Problem," Public Interest 6 (1967): 4.

procedures that create a permanent record every time a police officer's radar gun clocks a speeding vehicle do so in order to prevent the unfairness that is created when police ignore violations by prominent officials or by people who offer them bribes. These same procedures, however, make it impossible for the police to overlook someone speeding a sick friend to the hospital.[14] Similarly, the centralized control needed to increase coordination may directly conflict with the decentralization dictated by the aim of reducing bureaucratic insulation. Creating regional offices of federal agencies may effectively improve contact between bureaucrats and the citizens they are serving, but it may make it more difficult for agencies to ensure that their various activities work in harmony.[15]

Debate about democratic control of administration is further clouded by disagreement about what democracy means, and hence about what it means to control a bureaucracy democratically. Perhaps because the claim is so desirable, advocates use the adjective democratic to describe a host of institutional arrangements.[16] Some of these arrangements are designed to secure the liberties

[14] Jerry L. Mashaw explicitly discusses the consistency/flexibility trade-off in terms of disability decision making in his Bureaucratic Justice (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), pp. 86–87. Eugene Bardach and Robert A. Kagan discuss it in terms of the problem of regulatory unreasonableness in their Going by the Book (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1982).

[15] A. H. Birch, writing not about bureaucracy but about the more general issue of "responsible" government, detects similar confusions and conflicts of meaning. He uncovers three meanings for the concept "responsible": responsiveness, consistency, and accountability. "Responsiveness and consistency are desirable ends that are wholly compatible only in rare combinations of circumstances. Accountability is not an end in itself so much as a means whereby one or (to some extent) both of the other ends may be secured (Birch, Representative and Responsible Government [London: George Allen and Unwin, 1964], p. 131).

[16] C. L. Stevenson discusses words like "democracy" that "have both a vague conceptual meaning and a rich emotive meaning. The conceptual meaning of them all is subject to constant redefinition. The words are prizes which each man seeks to bestow on the qualities of his own choice" (Charles Leslie Stevenson, "Persuasive Definitions," Mind 47 [1938]: 333).

of the citizenry, some to ensure that government achieves the wishes of the citizenry. Some arrangements emphasize the role of groups in government, others the role of individuals. Proponents of each arrangement allege that it furthers the goal of democracy, but the characteristics of that goal are quite diverse.

When the element of control is added to the concept of democracy, the waters become still murkier. Some bureaucratic reforms have been proposed in the interests of democracy that in fact have little to do with control. The suggestion that public agencies should be staffed by individuals representative of the general population is an example.[17] To the extent that such staffing policies provide a weak form of control by the groups the administrators are representatives of, they indeed are an example of democratic control. However, arguments for such staffing patterns are often made in the interests of fairness or of making people feel closer to their rulers. Such goals may be important for a democracy, but they are not the same as democratic control. Similarly, some have seen democratizing the internal workings of an agency as an important component of a reconciliation of democracy and bureaucracy.[18] Internal democracy is not, however, a means of democratic control and in fact may provide a serious impediment to the exercise of such control by substituting self-rule for popular rule.[19]

[17] This position typifies what has been called the representative bureaucracy approach to public administration. See, for example, J. Donald Kingsley, Representative Bureaucracy (Yellow Springs OH: Antioch Press, 1944), and Samuel Krislov, Representative Bureaucracy (Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1974). Frederick C. Mosher takes a similar position when he argues that the educational channels to administrative jobs should be open to all segments of society (Democracy and the Public Service [New York: Oxford University Press, 1968], chap. 2 and pp. 215–19).

[18] See, for example, Warren G. Bennis and Philip E. Slater, The Temporary Society (New York: Harper Colophon, 1969).

[19] On this issue, see, for example, Blau, Dynamics of Bureaucracy , pp. 264–65; M. R. Godine, The Labor Problem in the Public Service (Cambridge MA: Harvard

University Press, 1951), pp. 45–51; or Peter M. Blau and W. Richard Scott, Formal Organizations (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1963), p. 55.

If we are to be selective about where the laurels of democratic control are bestowed and clearer about the kinds of choices we make when we choose a means of control, we must consider all control mechanisms together. Looked at singly, the details of a given plan stand out. Looked at together, the contours of the problem stand in relief. To see these contours we need a map showing the various possible routes to the goal of a democratically controlled bureaucracy.

Bureaucratic Democracy

Bureaucracies pose a problem for democracy when they make governmental decisions—that is, public policy—and thereby short-circuit electoral channels of public control. Electoral controls themselves may not always be effective, but short circuits in them further increase the potential for significant governmental actions to be taken in the name of the public without being influenced by the public. This problem is lessened, or avoided, if the range of acceptable bureaucratic behavior is in some way limited or constrained so that the public exerts control over decision making. Hence, the idea of constraint is the essential component of all mechanisms to be included in my map.[2O]

Defining the problem as one of constraint allows us to cast a wide net, a net that catches most of the ways the issue has typically been discussed. Accountability, responsibility, and responsiveness all imply setting some limits on bureaucratic behavior.[21] What varies is which aspects

[20] Herbert J. Spiro, writing about bureaucratic accountability, similarly argues that the goal of restraint is common to all views of accountability (Spiro, Responsibility in Government [New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1969], p. 98).

[21] A. H. Birch distinguishes three ways for popular control to be exercised: through advance instruction, via post accountability, or by means of

competition of elites. All of these applied to the bureaucratic arena involve a degree of constraint, if only that indirectly imposed by an elected official who is eventually held responsible for the action of bureaucrats in his or her administration (Birch, Representation [London: Pall Mall Press, 1971], pp. 112–14).

of bureaucratic behavior are constrained, and how tightly. Is the constraint the relatively loose requirement that administrators "respond" to the needs of the people, or the tighter one inherent in precise legislative formulas for the distribution of funds? Does the constraint center on prohibiting corruption or favoritism, or does it entail specifying the goals or policies the bureaucrats must pursue?

All behavior is in some way constrained, of course, whether by the values of an individual actor, by the resources that actor has available, or by formal limits on what may be done. What transforms constraint into democratic control is its imposition by a democratic political actor—either the citizens or their elected representatives. This may be done by citizens acting alone or in groups, by elected legislators or executives. It may be done directly through command or indirectly through an intermediary such as a politically appointed executive. It may be done negatively through sanctions against certain forms of action or positively through incentives to behave in specified ways. All that is essential for my purposes is that a mechanism impose constraint on bureaucratic behavior, that it be legal, and that the constraint be directly traceable to the citizenry.

The last condition is crucial. Mere congruence of bureaucratic action with citizen wants does not constitute control. If by happy coincidence bureaucrats act the way citizens want them to, bureaucracy may seem to be less of a problem, but it is not under democratic control.[22] As

[22] For a discussion of the problematic relationship between the actions of democratic political institutions and the achievement of citizen wants, see Douglas W. Rae, "Political Democracy as a Property of Political Institutions," American Political Science Review 65 (1971), pp. 111–19.

Robert Dahl explains, control is "a relation among actors such that the preferences, desires, or intentions of one or more actors bring about conforming actions, or predispositions to act, of one or more other actors. Control is thus a causal relationship: the actions of one actor are interpreted as having been brought about, or caused by, the preferences of other actors."[23] Without the hand of the citizen, democratic control of bureaucracy does not take place.

Control may occur through a process of anticipated reactions. If bureaucrats accurately anticipate what the hand of the citizen would do, and then feel constrained to act on the basis of that anticipation, a form of democratic control has occurred.[24] If the bureaucrats are wrong in their anticipation and act in ways the citizenry or legislature does not approve of, however, it cannot be said that their actions have been controlled by the citizenry.

Idealized Perspectives

Two basic aspects of bureaucratic behavior may be subject to constraint: the procedures used to make decisions and the substance of the decisions actually made. Procedurally, an administrator may be required to hold hearings, to consult certain groups before taking action, or to hire personnel in a prescribed fashion. Substantively, the administrator may be limited, for example, to making decisions

[24] As Dahl explains, "control need not be intentional; it may also be unintentional. Although Beta's action x must be brought about by Alpha's preferences, desires, or intentions, Alpha need not specifically desire or intend that Beta do x . What is crucial is that Alpha wants x to occur (or wants the results of x ), and that, as a result, Beta does x " (Dahl, Dilemmas , p. 17).

that serve to increase the amount of rice produced in the country or that provide low-cost housing for the elderly.[25]

The distinction is not absolute. "Procedure" and "substance" are in part determined contextually. The holding of public hearings may at one and the same time be the process by which decisions are made and the substantive result of an earlier decision about how to proceed. Procedure may also be a determinant of substance. The way a decision is made can significantly influence it. Nonetheless, the distinction is both heuristically useful and practically applicable. Every decision has both a procedural aspect and a substantive component. Either or both may be constrained through specific control mechanisms.

Constraints do not merely exist or not exist; they can be imposed in varying degrees. The more constrained behavior is, the smaller the range of permissible alternatives open to the bureaucrat—that is, the less his or her discretion. A central point of contention among theorists and practitioners concerned with reconciling bureaucracy and democracy has been just how much discretion a bureaucrat should have. It was a major issue in the early colloquy between Carl Friedrich and Herman Finer on the nature of administrative responsibility.[26] It remains

[25] Other analysts have used similar distinctions to characterize a variety of political phenomena. Hanna Fenichel Pitkin describes both formal and substantive approaches to representation. The former are concerned with institutions and rules; the latter focus on purpose, intention, and motive (Pitkin, The Concept of Representation [Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1972], p. 238). Joseph Tussman argues that there are "two great moods of deliberative life," the purposive and the casuistic, or legal (Tussman, Obligation and the Body Politic [New York: Oxford University Press, 1974], p. 86). While realizing that "the interplay of purpose and law … is constant," Tussman nonetheless is able to "imagine a scale or spectrum marked at one end 'rule dominated' and at the other end 'purpose dominated'" and then to locate tribunals on the scale.

[26] Friedrich, "Public Policy," p. 6; Herman Finer, "Administrative Responsibility in Democratic Government," Public Administration Review 1 (1941): 335–50.

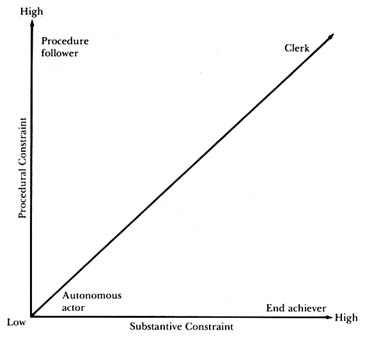

Figure 1. Idealized Perspectives of Bureaucratic Democracy

an essential difference among proposals for bureaucratic control today.

Control mechanisms are located on the map, then, on the basis of two variables: the degree to which the mechanism constrains bureaucratic behavior and whether it is the procedure by which bureaucrats make decisions or the substance of those decisions that is constrained. The borders of the map consist of two axes—procedural constraint and substantive constraint—with each varying from low to high. (See Fig. 1.)

Before going on, two things should be stressed. First, this is a map of mechanisms for democratic control of

bureaucracy, not a map of all the ways bureaucratic behavior may be constrained. Some mechanisms that in fact tightly constrain the behavior of bureaucrats do not appear on the map because the constraint does not derive from the citizens. For example, virtually all bureaucrats are constrained by the abilities of the people working for them and the limited capacity of complex organizations to harness those abilities. These constraints are a form of democratic control only insofar as they are a product of public pressures or decisions.

Second, discussions of more or less constraint should not be interpreted as discussions of more or less democracy. Whenever constraint is exerted by the citizens or their representatives, some degree of democratic control of bureaucracy exists. As I argue in chapter 2, however, whether that control is sufficient depends on one's definition of democracy. Fairly weak forms of control are congruent with some theories of democracy, but barely acceptable to others. Various positions on the map should therefore be interpreted as representing different, but not necessarily more or less, democratic visions of how a bureaucracy should be controlled.

Situated in the corners of the map are four idealized perspectives on how bureaucrats should behave in a democracy. Since they represent extreme cases, these perspectives are rarely, if ever, reflected in specific control mechanisms. Understanding them does, however, help to locate actually occurring proposals on the map and to clarify relationships among them.

In the lower left-hand corner, where both procedure and substance are very loosely constrained, is the bureaucrat as autonomous actor. Such a bureaucrat's actions may be competent, professional, and otherwise satisfactory to the citizenry, but they primarily result from his or her choice and not the choice of the citizens.

Diagonally opposite the autonomous actor is the democratically

controlled bureaucrat as clerk. Here, both procedure and substance are so tightly constrained as to leave the administrator no discretion at all. It is this vision that formed the basis of the old, extreme, and now largely discredited view that policy and administration are separable, and hence that all administrative action flows directly from democratically made legislative decisions. In caricature, the job of the bureaucrat is to determine what situation he or she is faced with and then to administer the "correct" treatment that has been previously determined by elected officials.

The upper left-hand corner of the map represents the situation where procedural constraint is high and substantive constraint is extremely low. This describes the bureaucrat as procedure follower. The orientation reflected here focuses on the importance of due process to the exclusion of other concerns. Bureaucratic decision making is considered consonant with democracy as long as closely specified procedures are followed; the substance of the decisions is left to the discretion of the bureaucrats.

In the lower right-hand corner is the democratic bureaucrat as end achiever. In this case, the substance of decisions is highly constrained, the procedures not at all. The bureaucrat's role is to secure publicly specified goals using whatever procedures he or she thinks best to reach those goals.[27]

Approaches to Democratic Control

These four cases define schematically how bureaucratic behavior may be constrained, and hence democratically

[27] A. D. Lindsay expresses this vision as follows: "Government [is] … given a free hand to deal with means. The purpose of the control exercised by the ordinary voters is to see that those means—the technical skill of the administrative—are used to the right ends" (Lindsay, The Modern Democratic State [London:Oxford University Press, 1969], p. 276).

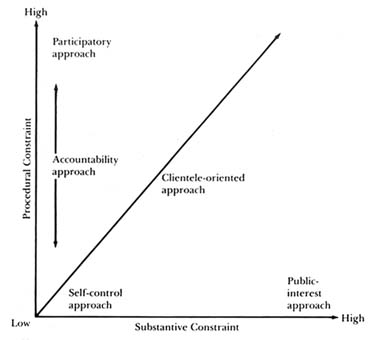

Figure 2. Approaches to Democratic Control

controlled. In the space between them we can locate various specific proposals arising both in social science literature and in popular discourse. I have grouped commonly occurring proposals into five broad approaches to democratic control: (1) control through participation, (2) control through clientele relations, (3) control through pursuit of the public interest, (4) control through accountability, and (5) self-control. Each of these approaches occupies a portion of the map, although the specific features of any given control strategy determine its exact placement. (See Fig. 2.) Each approach implies a

different perspective on why we need to control bureaucracies and on how to go about doing it.[28]

1. Participatory control lies near the top of the map where procedural constraint is high. According to proponents of this approach, the problem with public bureaucracies is that they are isolated from the public, and hence are closed, undemocratic institutions. To counteract isolation, highly constraining procedural changes, such as community participation requirements, are advocated. All such changes center on increasing direct citizen involvement in decision making.[29] Many control mechanisms have participatory elements, but for those that lie in this region of the map participatory decision making is itself the goal. Many advocates of participatory reform assume that these changes will also produce change in the nature of policies, and hence substantive constraint. However, since the essence of participatory reform lies in changing the way decisions are made, substantive constraint is ancillary.[30] Constraining procedures to increase the citizen role does not inherently imply constraining

[28] There are parallels between these approaches and those several other scholars have suggested. Douglas Yates contrasts two models of bureaucracy, an administrative efficiency model and a pluralist model. The former, based on Woodrow Wilson's ideas about neutral competence, is similar to my approach of self-control; the latter is similar to the clientele approach (Yates, Bureaucratic Democracy [Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1982], chap. 2). Jerry Mashaw describes three models for administrative justice: bureaucratic rationality, professional treatment and moral judgment. The first emphasizes the accurate realization of legislative will and is a cousin of the public interest approach discussed below. The second emphasizes the appropriate use of professional expertise and is cousin to self-control. The third emphasizes the fairness of the process through which decisions are arrived at and is cousin to the accountability approach (Mashaw, Bureaucratic Justice , chap. 2).

[29] Authors such as Milton Kotler, Neighborhood Government (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1969), and Marilyn Gittell, Participants and Participation (New York: Praeger, 1967), are typical of this perspective.

[30] This point is made by L. Harmon Zeigler and M. Kent Jennings, Governing American Schools: Political Interaction in Local School Districts (North Scituate MA: Duxbury Press, 1974), pp. 8–9.

substance as well, and certainly not constraining it in a predictable way.

2. Clientele-oriented proposals, in contrast to participatory ones, are more concerned with the substance of decisions made in administrative agencies than with the procedural fact that they are made solely by administrators. Public agencies are seen as being undemocratic because their decisions inadequately serve the needs of citizens.[31] This substantive orientation is, however, linked to a procedural diagnosis of the problem—insufficient communication between bureaucrats and their clients. The clientele-oriented approach thus occupies a position near the center of the map, where both procedure and substance are moderately constrained. Constraint is moderate because advocates of this approach seek input and guidance from clients, not strict specification of action. Procedure is constrained primarily through requirements that administrators consult representatives of the groups most affected by the decisions being made, generally through advisory groups or panels.[32] Such consultation differs from that sought by advocates of participatory control in that the latter value involvement for its own sake, whereas clientele-oriented strategists seek more limited agency-citizen contacts to transmit information about the needs and values of client groups. By the same token, since the consultation is designed precisely

[31] Herbert Kaufman describes this approach (Red Tape [Washington DC: Brookings Institution, 1977], pp. 47–48). Philip Selznick, TVA and the Grass Roots (New York: Harper and Row, 1966), H. George Frederickson, "Toward a New Public Administration," in Frank Marini, ed., Toward a New Public Administration (Scranton PA: Chandler, 1971); Avery Leiserson, Administrative Regulation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1942); and David B. Truman, The Governmental Process (New York: Knopf, 1951), pp. 457–67, are among the authors who fall within this perspective.

[32] Unfortunately, how to determine which groups are affected (or, for that matter, who should participate in the previous approach) is rarely specified clearly.

to produce substantive changes in agency policy, clientele-oriented strategies are more substantively constraining than participatory.

3. In contrast, what I call the public-interest approach to democratic control is predicated on the assumption that, far from being inadequate, contact between bureaucrats and individual citizens or group representatives is pervasive. Policies emanating from bureaucracies are seen as fragmented or overly geared to the interests of particular groups. For proponents of the public-interest approach, the hallmark of a democratically controlled bureaucracy is that its decisions serve collective interests. In Sheldon Wolin's words, "'Political' responsibility has meaning only in terms of a general constituency, and no manipulation of fragmentary constituencies will provide a substitute."[33] The public-interest approach is oriented almost entirely toward constraining the substantive aspects of bureaucratic behavior, and therefore lies near the lower right-hand corner of the map. Advocates of this approach presume that elected officials will act to further more general interests (though of course in practice they often do not). Control mechanisms revolve around ways of increasing the reach of these officials into bureaucracies, making bureaucrats more responsive to the expressed policy initiatives of elected officials.[34] A moderate form of this approach is reflected in efforts to increase the number of political executives in administrative agencies

[33] Sheldon Wolin, Politics and Vision (Boston: Little, Brown, 1960), p. 433. Other representatives of this approach include Theodore J. Lowi, The End of Liberalism (New York: Norton, 1969), and Mosher, Democracy and the Public Service , especially pp. 165–75.

[34] Proponents of this perspective have almost always written about bureaucracies on the national level, but a comparable position could be taken from the perspective of states or cities. In that case emphasis would be placed on meeting statewide or citywide needs, and the desired responsiveness would be to governors and state legislators or mayors and city council members.

because these executives serve as conduits for the substantive decisions of elected presidents, governors, and mayors.[35] It is also reflected in line-item budgeting designed to allow elected officials to direct how money should be spent. A stronger manifestation is the advocacy of decreased bureaucratic discretion through increased substantive decision making by Congress and other legislative bodies, including those at the neighborhood level.[36]

4. Procedure, not substance, is the focus of the accountability approach.[37] These proposals lie in a vertical band on the left of the map, where procedural constraint runs from moderate to high and substantive constraint is low. The emphasis on procedure derives from the diagnosis that bureaucracies threaten democracy when they abuse their power by acting corruptly, inefficiently, or unfairly. Procedural safeguards, or limits, are therefore advocated to ensure that such abuses do not take place. These constraints are generally directed only at limited aspects of agency behavior and are therefore usually less constraining than participatory reforms aimed at changing the fundamental processes through which agencies reach their decisions. Accountability mechanisms include codes of ethics, civil service systems, and hearing and notification requirements. They also include reforms aimed at facilitating the review of agency decision making such as freedom of information acts, ombudsmen, and oversight boards. All of these focus on guaranteeing that decisions

[35] Mosher, Democracy and the Public Service .

[36] Lowi, The End of Liberalism . For discussions of neighborhood based "legislatures," see Robert K. Yin and Douglas Yates, Street-Level Governments (Lexington MA: Lexington Books, 1975).

[37] Authors who have written in this tradition include: Finer, "Administrative Responsibility"; Joseph P. Harris, Congressional Control of Administration (Washington DC: Brookings Institution, 1964); and Walter Gellhorn, When Americans Complain (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1966).

are made in an "appropriate" fashion, with only peripheral concern for what the decisions are.[38]

5. Finally, there are those who say democratic control lies primarily with the administrators themselves. This approach of self-control is based on weak, usually indirectly imposed, external controls, and it therefore lies near the lower left-hand corner of the map. A mild form of this perspective is found among those who believe that control emerges from a process in which bureaucrats discern the limits of behavior the public will tolerate and then act within those limits. Proponents of a stronger, and therefore less constraining, form of this perspective assert that bureaucrats must serve the public, but that often they alone are in the best position to determine how to do so. In fact, for these people many more "political" forms of control work against the goal of public control.[39] For them, democracy is achieved by relying on bureaucrats' professionalism,[40] their sense of personal fulfillment,[41] or their background.[42] Many of these mechanisms, however, verge so closely on complete self-control that they scarcely lie within the borders of our map.[43] They may represent ways to achieve goals desirable in a democracy, but that does not make them democratic control.

[38] For a discussion of the argument that accountability need not always imply substantive responsiveness, see Michael A. Baer, "Interest Groups and Accountability: An Incompatible Pair," in Scott Greer, Ronald D. Hedlund, and James L. Gibson, eds., Accountability in Urban Society: Public Agencies Under Fire (Beverly Hills CA: Sage Publications, 1978), pp. 217–23.

[39] This is argument is discussed by Martin Meyerson and Edward C. Banfield, Politics, Planning and the Public Interest (New York: Free Press, 1955), pp. 38–39n.

[40] Friedrich, "Public Policy," pp. 12–14.

[41] Stephen K. Bailey, "Ethics and the Public Service," in Roscoe Martin, ed., Public Administration and Democracy (Syracuse NY: Syracuse University Press, 1965), pp. 283–98.

[42] Kingsley, Representative Bureaucracy , chap. 12.

[43] See, for example, Suleiman, Politics, Power and Bureaucracy in France , p. 158, for a critique of the reliance on "representative" background characteristics as a means of securing a democratic administration.

For even if the administrators in the end act in a way consonant with citizen preferences, if the action is purely at the behest of the administrators and not of the citizens, democratic control has not occurred.

Bureaucratic Attitudes

If the problem of reconciling bureaucracy with democracy ended with making an informed choice among various means of control, it would be complex, but, in the end, fairly tractable. Bureaucracies are not abstract administrative structures, however, but agencies filled with real people with their own interests and with considerable resources to resist control when it does not mesh with those interests. The exercise of control is therefore inevitably affected by those being controlled, the administrators themselves. The beliefs of these administrators, the roles they play, the histories of their agencies, and the resources they command all contribute to the way they will respond to specific efforts at control. As a result, it is crucial to understand the problem of democratic control from the perspective of the bureaucrats as well.

Bureaucrats can respond to control in many ways. Ideally, they will accept it and act the way controllers wish them to. They can, however, effectively hinder control. A governor, for example, may seek through a politically appointed agency head to step up the enforcement of state hazardous waste regulations, but if career administrators oppose the governor's intervention, they may deliberately slow down their investigations or do nothing to speed them up.[44] Under other circumstances bureaucrats may

[44] Donald P. Warwick argues that middle and low level administrators in agency "can protect their interests by tactics ranging from artful sabotage to surface compliance" if they fail to "socialize" the agency head (Warwick, A Theory of Public Bureaucracy [Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1975], p. 172).

accept the goals of a control-related reform, but not consider it a priority, and thus stymie the effort. For example, a school decision-making structure may provide for consultation between administrators and parents, but administrators may fail to bring proposals to the parent group consistently because of other demands on their time.

Democratic systems rely on the willing acceptance of governmental procedures, and in this respect the influence bureaucrats have over control is but one example of a more general problem democracies face. Robert Dahl and Charles Lindblom argue that democratic structures depend on

the consciences, norms and habits of the people in the society, leaders and non-leaders alike. For it is these that define what uses of control are legitimate and what are illegitimate; what behavior is acceptable and what is not. And if these definitions, commands, permissions, and approvals prescribed by the norms, habits and consciences of the people are not appropriate to polyarchy, then no written constitutions, no guarantees, no prescribed codes, no laws will achieve it.[45]

Unfortunately the ubiquity of complaints about recalcitrant bureaucrats suggests that bureaucrats do not always hold attitudes conducive to democratic control.[46] An appreciation of the bureaucratic perspective on control should, however, help us understand when such acceptance will occur and how it may be achieved.

From the perspective of achieving democratic control,

[45] Robert A. Dahl and Charles E. Lindblom, Politics, Economics and Welfare New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1953), pp. 287–88.

[46] Recent cross-national research has found that bureaucrats hold quite different political beliefs than politicians (Aberbach, Putnam, and Rockman, Bureaucrats and Politicians ). These findings suggest a further reason why bureaucratic attitudes may not easily coincide with political efforts at control and thus why willing acceptance may be problematic.

all bureaucrats share the key characteristic of being appointed policy makers. But bureaucrats operate in a great variety of policy arenas, and it would be surprising if the attitudes of all bureaucrats were the same; it would also be surprising if we chose the same means of control for all of them. Citizens are likely to place much less value on flexibility, for example, in the nuclear regulatory arena than in the social services arena. Equally, the attitudes of highly professionalized NASA scientists are likely to be different from those of Social Security administrators. Thus a full understanding of the problem of controlling bureaucracies also requires an examination of the policy context in which control takes place.

I have begun to explore the problem of controlling bureaucracies by creating a common framework for assessing various methods of democratic control, a map in which proposed methods can be arrayed, and hence compared. Chapter 2 expands the framework by considering normative concerns. There I show how the instrumental question of the choice of a control mechanism is embedded in larger issues of democratic theory. In chapter 3 I turn to the question of the costs incurred by various forms of constraint.

Chapters 4, 5, and 6 introduce two complications to the choice among mechanisms to control bureaucracies: the attitudes of the bureaucrats being controlled and differences among the policy areas in which control takes place. In chapter 4 I switch perspectives from that of the democratic controller to that of the bureaucrat to explore how the problem of democratic control looks to them. On the basis of interviews with local administrators working in the fields of education, fire, and housing, I examine how bureaucrats see their own role in the policy-making process and how they reconcile resistance to external control

with acceptance of democratic norms. In chapter 5 I begin the discussion of policy context by looking at how differences among policy areas may affect the values would-be controllers seek from control and affect the likelihood that the costs of control will in fact be incurred. In chapter 6 I extend the analysis of policy context by comparing how administrators working in different policy arenas view other political actors and hence the issue of control. Finally, in chapter 7 I leave the world of the bureaucrat and return to that of would-be controllers and discuss the lessons this research may teach them.

In sum, I seek to illuminate the general problem of how to impose democratic control on public administrators. To do this, I provide a structure for understanding the democratic values implicit in different means of exercising control and for evaluating the costs and benefits of various forms of democratic control. With this in hand, I don the lenses through which the administrators themselves view the problem of control. Together, the structure and the lens should aid us in understanding the choices, problems, and prospects of ensuring that our bureaucratic society remains democratic.