Out of Eden:

On Alberto Giacometti

Sailing to New York in 1965 for the opening of the big retrospective show of his work at the Museum of Modern Art, Giacometti wrote a preface to the collection of drawings later published as Giacometti: A Sketchbook of Interpretive Drawings . For many years he had made copies of images originated by others—a Rubens at the Borghese Gallery, a Pinturicchio at the Vatican, a Matisse or Egyptian sculptures in Paris, a Japanese print at his family home in Stampa. During his transatlantic voyage, in his mind's eye he suddenly saw those images as an interfused but not undifferentiated community of forms: "How can one describe all that? The entire art of the past, of all periods, of all civilizations rises before my mind, becomes a simultaneous vision, as if time had become space." To his consciousness, any interval of time could be transformed into a concentrate of space; that continuous transformation was the purpose of his daily work as an artist. His painting and sculpture do not represent or dramatize time's passing and the changes it exacts. They translate the feeling of time—of present, past, and what his friend Sartre called the "project" of the future—into spatial relations, the most crucial being the changeful pressure of an empty immensity on the figures that inhabit it. The forms for which Giacometti is best known, the skinny bronzes that seem unconquerably alert to the unhoused distances on which they fix their gaze, are leached of anecdote. Though many of the figures are in some gesture of motion or stand in an attitude out of which motion might ensue, they have been exiled from narrative time. This could be said about most figurative sculpture. But in Giacometti's things time is converted into the turbulence of matter laboring against the flaying, laying purgatorial force of space. It is the torment of contingency. Giacometti wanted to cast or fix the action of the pressure ("as if time had become space") that he described in his preface. But in the course of his life's work he achieved something else of profound importance for the life of forms in our lives. In the dizzying, cavernous oil portraits and the fibrous bronze stalks of men and women standing,

walking, pointing, Giacometti made manifest the heroism of the encounter between the visible world and the testimonial eye, an encounter unavoidably inaccurate but driven by a fanatical self-revision and endlessly readjusted decisiveness. That was the empowering torment of his career, the products of which remain, in their startling resoluteness, magisterially unfinished.

As an undergraduate in the mid-1960s I used to frequent a small gallery in Philadelphia that once had on sale a small Giacometti pen-and-ink drawing of three figures. I remember it now as a skeletal revision of one of Cézanne's cardplayer groups. (Giacometti in fact made copies of The Card Players in the Metropolitan and also the one in the Barnes Foundation.) It called attention to itself not only because a master was being candidly answered by an obviously fervent admirer but because the answer was rendered in the feverish idiosyncratic exploratory style of a great successor. Like so much of Giacometti's work, even that unambitious sketch manifested the very process that brought it into being; the racing loops and slashes conjured figures that argued themselves into existence from the creamy void of the surround. As a "copy" it was a portrait of emergence. Probably dashed off like most of his drawings—he threw away bins full of those preserved from the hundreds more he drew, incessantly, on newspapers, napkins, magazines, tablecloths—it was as complete, as finished, as anything else he did. Which is to say that it was a completely realized failure to reproduce what his eye actually saw. Cézanne was in this, as in so many things, an exemplar. "Cézanne never really finished anything," Giacometti once remarked. "He went as far as he could, then abandoned the job. That's the terrible thing: the more one works on a picture, the more impossible it becomes to finish it."

An artist's confident feel for his materials can induce a chastening persuasion of failure, because a feel for materials intensifies one's vision of the perfectibility of the work. Giacomo Leopardi, one of the most diligent students of the failure of aspiration, wrote in his daybooks in 1821: "The more you understand the materials of your work, the more you see them and feel them in your own hands, the easier it becomes to push beyond, farther and farther, and to perfect even that which seems already perfect." This is also a

condition of self-nurturing despair: so long as everything is in process of the realization of perfection, perfection is impossible. For Giacometti, perfection was the accurate representation in plastic forms of his retinal vision of reality. His vision, he insisted time and again, was not penetrative, not a seeing into the essence of things. Nor was it illustrative of a view of the human condition. (On my visits to that Philadelphia gallery I sometimes carried with me William Barrett's Irrational Man, the cover of which bore a reproduction of one of the tall walking figures that had had the unfortunate effect of ordaining Giacometti existentialism's resident iconographer.) Giacometti's task was not expressionistic. He wanted merely to re-present the look of the object as he viewed it in its space. His vision of things, in his plain and direct terms, was his own kind of idealization. The oldest description of this desire and frustration is probably Vasari's remark about Leonardo, who "through his comprehension of art, began many things and never finished one of them, since it seemed to him that the hand was not able to attain to the perfection of art in carrying out the things which he imagined." The persuasion of the unfinishable is not therefore an exclusively romantic or modernist trait. It is the quality of a particular kind of artistic intelligence, one that treats all its products as projects; its intentions are always in process of redefinition or of merely provisional resolution. Giacometti's art is heroic because the struggle with impossibility is emergent and fully articulated in the actual work of his hands, undeflected by ironic elusiveness or righteous declamation. His way of looking at things was so intense that his conception of a possibly perfected representation of a dog or cat, a human head (the dome, he called it), an arm, leg, nose, wheel, "base" or place, was impossible to realize. He was fated by the plasticity of his materials never to succeed at anything. "Everything fails," he said. The only difference is of degree. He complained, perhaps a little impishly, that if only he could find an artisan with the technical virtuosity to represent what his own eye actually saw, then he might be able to satisfy himself.

The crisis of representation was complicated by his working methods. In a sense, his methods were the motor that drove the machinery of failure. More than earlier artists like Leonardo, Gia-

cometti was caught up in the changeful life of his materials. The process of plastic emergence—the kneading, the paring, the hacking and gouging with knife and spatula—was an enactment of the stress of distance between his eye and its object of vision. Every figure he made in his later period acknowledges and measures that stress. Many kinds of representationalism follow, in their effects, the program of Browning's protorealist, Fra Lippo Lippi: "We're made so that we love / First when we see them painted, things we have passed / Perhaps a hundred times nor cared to see; / And so they are better, painted—better to us." Art, under this prescription, restores to us the timeliness of visible reality, which is morally improved in its representations. It is art as visual and moral enhancement that stuns us momentarily out of the dulled wits of habit. Though we know from his youthful drawings and paintings that Giacometti from the beginning possessed prodigious skills as a realist, he was concerned not so much with imaginative enhancement as with the process by which new images are forged. If realists of Lippi's (and Browning's) persuasion are most concerned with resolution of image and moral effect, Giacometti is instead committed to impassioned, inconclusive deliberation. For him, the measure of the image-making process is the squeeze or exhalation of space around the figure, and the continued snags and ravelings of stress within the material itself. From roughly the mid-1940s until his death in 1966, his chief work was to make manifest the strain of pure becoming. Because his paintings and statues record for us the quickened movements of his imagination—interrogatory, abrasive, reclamatory, nurturing, corrective—we become second witness to the way the imagination may be lived in and through. When he traveled to Stampa to visit his family, and on the few occasions when he was hospitalized, Giacometti always took along in shoeboxes (or matchboxes) clay figurines wrapped in damp rags, which he would work on whenever possible. He was always working. And it was not a mere busyness or neurotic activity, for "work" was the constant formative exercise of skills on material that might eventually, miraculously, coin the perfect representation of what he ordinarily saw. I do not know of any other artist of our time who,

crowded by the exempla of the enormous simultaneous past, so matter-of-factly conducted his art at the margins of what is possible.

The more than two hundred paintings, drawings, and sculptures that have been on view at the Gianadda Foundation in Martigny, Switzerland,[*] show the entire crisis-laden stream of Giacometti's career, from the crayon sketches done in his teens, through the tough uncertainties of the surrealist period, to the wise and solemn busts of Elie Lotar in 1965. The problem of the fated failure of his materials emerged in 1921, when he was trying unsuccessfully to finish a simple female bust. He later described his feeling of doomed ineffectuality as an expulsion from paradise: "Before that, I believed I saw things very clearly, I had a sort of intimacy with the whole, with the universe. Then suddenly it became alien. You are yourself; and the universe is beyond, which is altogether incomprehensible." He felt himself cast out of the familiar community of representational forms. The loss of clear vision meant the loss of the primordial home where there was an immediacy of relation, almost a simultaneity, between the thing seen and its imitation in paint or clay. Once expelled, he had to bear the curse of work, and his major chore would be the recovery of that now lost oneness. By 1925 Giacometti was already in exile from the figural in his sculpture, though not in his painting, where he managed to sustain sculptural feeling in his way of working the paint. In a self-portrait of 1921, the artist's three-quarter profile twists back toward us over his shoulder, his gaze defiant, void of wishfulness. The quilted coloring, both here and in a larger, more frontal self-portrait of 1923, is strongly suggestive of Cézanne's, but the action of the paint is muscular, the textures so dense that you feel the image has been modeled out of paint.

In his sculpture, however, Giacometti at that time was feeling more and more estranged from the human figure. Familiar definitions began to melt away. The features on the series of heads that he did of his father in 1927—in marble, granite, and bronze—are

* May 16–November 2, 1986.

nearly reabsorbed into the blank of the material. All suggestion of skeletal and carnal expressiveness is being planed away. The figure retreats more and more furtively into the anonymity of stone slugs. It's astonishing that, feeling himself expelled from his Eden, Giacometti did not collapse into chaos or despair. Instead, he struck his own temporary bargain with vision by resorting to a thesis: Sculptural representation is not emergence, it is arrangement, of concave and convex surfaces presented as idealized abstractions of natural forms. As a consequence, many of the pieces he produced in the late 1920s and early 1930s are spookily clean—polished and purged of all traces of the artist's exertions. They are a kind of willed (or trumped up) deliverance. The Gianadda show displays two versions of Tête qui regarde executed between 1927 and 1929. (The English title, Head, doesn't suggest the activity of looking which Giacometti intended; several of his early works are entitled simply Tête. ) These are rectangular broadside slabs of glassy marble or bronze, druidic, anonymous, recondite. On the left side of the slab is an upright lozenge-shaped depression, on the right a concave ovoid. The effort behind these works is, I think, primarily to smother or conceal figural inflections. Their energy is all invested in a tremendous holding back of the will to externalize, to manifest. These are not negligible works, nor are they formal dead ends. Thirty years later, in the busts of his brother Diego and his wife Annette, that slab, ridged and roughened by the swarming return of human features, will turn to face us, like the jagged blade of a ruined ax head. Convinced as he was in the 1920s and 1930s of the failure of his vision ("Before that, I believed I saw things very dearly") Giacometti coded into those near-blank forms, into the Tête qui regarde, the disappearance or unfindableness of the human gaze.

The concave impression became a more important, and less mystifying, physiological sign in Giacometti's female figures. In a hermetic monumental bronze like Woman (plaster, 1927–28; cast in bronze, 1970), the round scoop of the feminine occupies nearly half the statue's surface. It's an abstract work insofar as it is abstracted from, not representative of, the image in nature, and like much of Giacometti's work from this period it is guarded and

affectless—it might be a signpost, menhir, or club. The best known and most statuesque in this family of forms is the large bronze Spoon Woman of 1926. Her entire torso is a concavity, a cobra hood spread atop a narrow pedestal. The Spoon Woman has a strange talismanic effect. You sense sexual force momentarily in check, but with possibly tremendous engulfing power. Formally, it is assertive, exercising the traditional sculptural sovereignty of matter dominating and restructuring its surrounding space. But its stolid forms take the edge off sexual menace. The torso catches available light in its shallow bowl, but there is nothing reactive in that encounter. The avoidance or difficulty of giving more immediate expression to sexual force led Giacometti finally to the operatic expression of sex fear in Woman with Her Throat Cut (1932), probably the most notorious of his works and the one that draws more shocked, titillated attention than any other single work he produced.

The sprung ribcage lies in shattered repose, but it is also a sex trap, the sharpened staves triggered to snap shut. The woman's legs, splayed wide as if hooked in delivery-room stirrups, push her pelvis up in a hideously ambiguous attitude of torment and availability. The impossibly long chain of neck vertebrae arcs forcefully upward like the legs and the inverted ladle of her belly. It's as if the studiously determined concavities of Giacometti's spoon women had been angrily pulled inside out. The almost hysterically expressed sexual dread in this image might be less outrageous if it were not also so programmatic. The horrific sentiment is worked out in contrived, semiabstract terms, the skeletal contortions, gruesomely pictorial, played off against the featureless abstraction of the upper torso and head. There's a vaguely spiteful glee in the tone—a woman murdered in what seems a moment of self-offering—which is the Surrealist's glee in overdetermined shock effects meant to outrage the norms of bourgeois pictorialism. Woman with Her Throat Cut is not a frivolous or wicked piece of work. Giacometti was temperamentally incapable of frivolity and uninterested in moral effects. But this and other things usually listed in the roster of his surrealist works (The Palace at 4 A.M., No More Play, Hand Caught by a Finger [Main prise], Disagreeable Object ) seem to

me productions of an artist so stricken by his fall from the Eden of innocent representations that he elects a program of contrived images as a stay against inactivity and as a willed continuance while he tries to find his way back. In any event, Giacometti lacked the snickering bad-boy wit and antic buoyancy of the surrealist intelligence. His troubles in the late 1920s and through the 1930s are evident in the impoverished plasticity of his materials. We do not see the clay and plaster toiling in the finished work. This is most conspicuous in the stacked angular catwalks of Reclining Woman Who Dreams (1929) and in the crossbarred penitentiary grid of Man (Apollo ) (1929), the two most industrial and architectural of his works in bronze, where his subject is not being reimagined in and through the material. Giacometti's exile from the garden is truly an Adamic drama in that he lost faith in his ability to model nature in clay. His chore thereafter, and his curse, was to win back that enabling faith. And that in turn required a journey of self-restoration toward a new Eden where he would never, could never, arrive.

He once told his biographer James Lord that all during the surrealist phase he knew he would sooner or later be obliged to go back to nature: "And that was terrifying, because at the same time I knew that it was impossible." There are signs of that return as early as 1932–35, the years of the tall tubular Nude and Invisible Object (Hands Holding the Void), with its owlish, contrite female visage. Though the spookiness of the surrealist mood is still on him, and although he even experiments with cubist volumes in The Cube and Cubist Head (both executed in 1934), Giacometti is being more attentive to the model. His return was contested at every point, however. The more he looked at the model, "the more the screen between his reality and mine grew thicker. One starts by seeing the person who poses, but little by little all the possible sculptures of him intervene. . . . There were too many sculptures between my model and me." His relation to the natural figure was hopelessly complicated by all the mediating serial possibilities of representation. That kind of plenitude freezes progress. In the searing magnificence of his later work we can actually read or imagine, in the heft and texture of the final "abandoned" product, the inter-

vening forms that mediated its progress. In light of the crisis he had to work through in the 1930s, it's remarkable that Giacometti did not seek shelter in self-glorifying parody or the preciosities of an "art of exhaustion." Instead, he absorbed the very threat of dissolution, or dissipation, into his newly developing form language as a kind of apotropaic act, to make his despair breathe deep within the formal life of the work. Around 1937 he tried to model a complete figure in plaster, a standing woman about eighteen inches tall. The figure grew smaller and smaller beneath the exertions of his knife until the needle of chalk crumbled. That was no self-canceling gesture. It was the as yet unredeemable consequence of an artist's desire to answer to his vision by interrogating his materials. It was form pulverized by the desire for form. In this respect, too, Giacometti is Cézanne's great successor, for both of them made the action of their materials—their work —supremely and devastatingly answerable to what their eye saw.

The emergence of the famous late style required a purging of vision. It required revelation. In 1942–43 Giacometti produces the first Woman with a Chariot . (The "chariot" is a nurse's cart he had seen in a hospital.) The figure already suggests the new sculptural form he is working toward: the woman stands upright, legs closed, hands locked to her sides, with little definition of feature except for the rather innocently exposed bulge of sex. In 1945 he produces two figurines, each mounted on an oversized square pedestal; both are about four inches high, including base. The figures are mere slivers, fantastically reduced versions of the human offered up like sacrificial victims on altars, or chopping blocks. In 1946 came the revelation. Watching a newsreel in a movie house, Giacometti suddenly realized that the screen image was just a montage of dots on a flat surface, whereas the reality around him, which until that moment he had always viewed photographically—as if the world were a composite of colored figures and swatches of light on flat surfaces—was something altogether different. He experienced what he called "a complete transformation of reality, marvelous, totally strange." Space thickened around bodies, pinching and abrading them. The body's topography roughened into sinewy, craterous exposures. The head seemed at once islanded and enraptured by its

aura of emptiness—the stricken skyward cry of Head of a Man on a Rod (1947) is one answer to that aura. Giacometti's new vision, to which he brought the intensity of gaze that he had been sharpening since childhood, was of a preternatural embodiment of the human form in nature. He was witness to, and forger of, a baffling restoration of appearances. The stress of space determines form, but space as a measure is itself changeful, indeterminate. That indeterminacy is caught in the molten eruptive surfaces of all Giacometti's later works in bronze, and it is momentarily held in check by the tentative housings—the boxes, bird-cage halos, and cloisters—that frame the heads in his oil portraits. The things from the major period seem to have been let go, released, only moments before we bear secondary witness to their becoming. The blistered erosions of the busts seem still to be cooling. The isolated gestures—the head on a rod; the outstretched arm with its bony, panicked hand; the alarmed stillness of a cat; the dirt hunger of a dog—seem each a pause in the stream of pure becoming. If Giacometti's is an art of agony, it is because at its heart is an agon, the contest between space and matter, and the intelligence that seeks to represent it. The slabs and blanks of the earlier work are gone, replaced now by the armature, the stake, where the work of the agon takes place.

With the emergence of the major style in the 1950s comes a more complex and fine-toned presentation of the female form. Each of the five statues from the "Women of Venice" series on exhibit at the Gianadda (Giacometti produced ten of them for the 1956 Biennale) bears a different sexual character. One figure's breasts are splayed, another's bulbous and low-slung, another's melted nearly flat. In each, though, the breasts are sexual eruptions on an otherwise disinterested heraldic stillness. The ambiguous sense in each is of power restrained and a haughty indifference to that power. The measure of sexual availability or offering varies statue to statue. One figure's hands are fused to her thighs, the pelvic area recessive, protected, with no hint of sexual availability. In another, the entire torso is brittlely concave, punched in, the belly reminiscent of the spoon-woman form; her shape bears an unembarrassed sexual welcome, but her face is twisted into a sneer or grimace. The apparently candid invitation is chilled by her sar-

donic, faintly contemptuous reserve. Giacometti's female figures never express the somnolent ecstasies of Brancusi's women, and they don't have the archetypal bombast of many of Henry Moore's queens and mothers. And yet the inflections of sexuality in his work are surprisingly rich. He commands nearly all the registers of the testing or trying out of sexual feeling, sexual mood. And unlike Brancusi's and Moore's representations of women, Giacometti's are not so easily owned by the male eye. Even when a figure seems most welcoming, its feeling tone is never pure; it is inescapably mixed with suspicion, regret, sullen withdrawal, or clenched aggressiveness. All this becomes painfully obvious by comparison with the most disconcerting and vulgar piece in the Gianadda show, the bust of Mlle Télé (1962), where coquettishness is rendered in such conventionally vampish terms—the lifted shoulder, the cocked head, the "fetching" expression—that the figure's sexual charm is trivialized. There is plenty of sexual charm in Giacometti's work, but it is effective (and true) only when blended with the sort of black magic that promises transformations at the edge of a darkness.

Like the free-standing constellation of the "Women of Venice," the Four Women on a Base (1950) is remarkable for the painstaking differentiation of the figures. One pouts, one grins (rather mischievously), another cringes as if fear-struck. The fourth and tallest is clearly the dominant member of the clan. Each sexual gesture is different, measurable by the half-closed hands flaring from the hips. The attitude of the figures, their stance, is a way not of occupying space but of inhabiting it, as if the air were their culture, shaping them while they shape it. Giacometti painted this and many other bronzes—often at the last minute just before an opening. After his breakthrough in the late 1940s, he could never leave his work alone: once back in his sight, "finished" paintings and sculptures were sucked again into the vortex of his desire for the impossible perfect representation. Usually, as in Four Women on a Base, he streaked or daubed the bronze with reddish, creamy, and grayish tints. The first effect is to dramatize the topography of the figure, to provoke a reaction from light's impingements on matter. But the effect is particularly odd with female figures, because it

makes them at once gaudier and more intensely secretive, their sexual character enfolded more cunningly in disguise. For all their diversity, the four figures share their platform, the elevated rail or ledge that anchors them in space and also binds them in a tribal relation. It locates them, naturalizes them, in what we can imagine to have been an unpopulated waste. From the 1940s on, the form that becoming takes in much of Giacometti's work is a risenness; the standing figures seem recently emerged from the ground—they are The First Ones. Before anything else they are expressions of vegetative force. Thus Giacometti gives the title The Forest to a group of seven standing figures and a small shrubby bust arranged on a shallow concave ground; and The Glade to a tribal grouping of nine odd-sized reedy figures. In both ensembles the human stalk rises from a warped, seething earth.

The genesis poetry prevails also in city representations. In Man Crossing a Square (1949) the forward lean of the figure across his public space is retarded by the strangely crystallizing elasticity of the ground. He uses his spatulate hands like paddles to coax his way freer of the earth's pull. The viscous space he moves through drags him back even more. And yet his head and face are gnarled with resolve, beautifully detailed in the knot of muscle at his jaw. Giacometti's walking figures inevitably have a purposefulness which the standing figures lack. If the standing figures suffer the air of contingency, the walking figures lean into it, resisting its sorrows. The movement of Walking Man II (1960) is the quotidian tilt of curiosity tensed toward some destination; it is the will impelling matter away from the mud pool. The squared, big-booted feet of walking and standing figures alike are the gritty, magmatic residue of material creation. The tree that Giacometti designed for a production of Waiting for Godot seems grown out of The Leg, which is seven feet high and looks like a young tree shattered by lightning. The two essential facts after the loss of Eden are that nothing is ever finished and everything in some way fails.

Giacometti's movie-house revelation deepened the sense of estrangement that followed his earlier loss of intimacy with nature, but it also initiated his journey into the mysteries of otherness, to-

ward a recovery of the visible world in the forms of sculpture and painting. In his late work the will to encounter and recover takes the shape of auroral greeting. Not a gesture of hopeful anticipation and not anything as vulgar as optimism, the greeting is a primeval moment in the strenuous task of becoming, in which the figure acknowledges and goes out toward that which is other. The mood of the greeting, especially in the busts Giacometti produced in the mid-fifties, changes from work to work—stoical, impatient, wondering, fear-struck, quizzical, arrogant, bemused—each expressing some sort of pained attentiveness on the long morning after the fall from Eden's golden unities. In Diego in a Jacket (1953), Diego with Sweater (1954), and Head of Diego (1955), all the inchoate force of the Titan's torso rises up and concentrates in the roughened, charred ridges of the narrow head, which inhabits only a slot in space. And yet we cannot see past it. Its gaze stops us. Its acute attention is so aggressively outwarding that it traps our attention in its greeting. The tragic energy of these works is plied into the gashed, restless textures of the bronze.

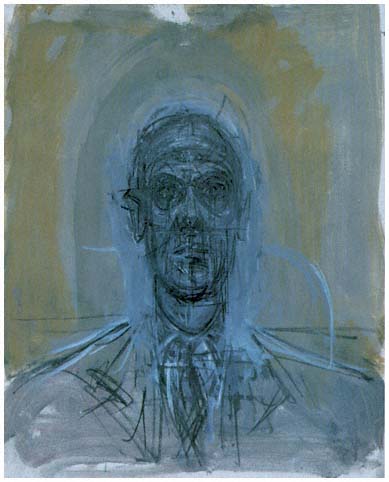

The relation between Giacometti's sculpture and painting is one of the major conversations in modern art. On canvas he could shape and color the action of space around his subject, then translate those relations back into the volume and elasticity of clay. The pressure built up in the sheer bulk of a sculpted torso could not be achieved in the frontal, two-dimensional presentation of portraiture. The auroral greeting in the portraits is therefore fanatically concentrated in the face and eyes. In Diego (1958), Head of a Man (1956; Plate 5), and Portrait of Yanaihara (1959), the head unscrolls from a bituminous murk—the greeting is an arduous attempt to see out of an enveloping darkness. We can feel Giacometti trying, unhappily and with his typical sense of fated failure, to hack resemblance out of the resistant mass of undifferentiated colors. In these and later oil portraits, as you look away from the wiry loops and nodes of the darkened face—the eyes are craters, instruments nearly burnt out by overuse—the paint thins out, the scarifying blacks and blue-grays run a feebler smoky white. Portraiture, like sculpture, was for Giacometti expressive of the agony of its making. Just as he painted his bronzes at the last minute, he could not leave

his paintings alone so long as they remained in his studio. In three portraits of Diego done in 1964, the image is a history of the passionate self-corrective energy that brought the image into existence. Giacometti made a whole art out of pentimenti . First to finishing stroke, each act of figuration was in some way a pentimento . It was the only way he knew to arrive at a representation of what he called "the simple thing seen."

Around 1964, the emotional tone of the paintings changes. The febrile gaze of the portraits from the 1950s softens to a more aloof self-containment. The greeting is not so electric with the possibility of surprise or revelation. By this time the sculptures have changed, too. The heads thicken, broadening and filling out into more classically spherical forms, no longer so whittled and crimped by space. The two busts of Diego from 1965 included in the Gianadda exhibition show at once tormented exertion and withdrawal, the neck craned forward, face buckled and sour, skull and shoulder cavities emaciated, cadaverous. The greeting is sustained only at great physical cost; the human form seems to be collapsing into itself, such is the effort to preserve its attentiveness. In an oil portrait of Diego from 1964, the subject's head is nearly lost to its black ground; out of the little dome shine splinters of light, like bird bones. The following year, however, Giacometti produced three of his finest works, the busts of Elie Lotar. Lotar was a sad, familiar figure in Giacometti's circle, a failed photographer, destitute and alcoholic. (Giacometti not only used him as a model but also more or less took him in, letting him run errands and do odd jobs around the studio.) The torsos of the Lotar sculptures are more combustive than ever, but out of that turbulence rises a solemn, piercingly handsome, imperial head. The calm, alert eyes, welling out of deep pouches, cast the unsurprisable gaze of a being who greets the world by awaiting its manifestations. Desire, expectation, anticipation, all evaporate in the dispassionate regard of Lotar's gaze. The human figure is not resigned, certainly not self-abandoning, but it is no longer driven or terrified either. The strain of becoming so elaborately inflected in the previous work momentarily resolves into a fearless amor fati, a condition just this side of irrational joy, though the figure expresses no joy at all.

Two of Giacometti's heroes were Giotto and Tintoretto. Early in his career he was overwhelmed by the Scrovegni Chapel frescoes, the figures "dense as basalt, with their precise and accurate gestures, heavy with expression and often infinitely tender." The weighty tenderness of the Lotar busts has its source in that early discovery. Giacometti said that Giotto replaced Tintoretto in his affections, though he had loved the Venetian's work "with an exclusive and fanatic love." And yet I think it is Tintoretto's influence that was most formative, especially for the work of Giacometti's later period. In formal terms, he took over the geometries of passion he found in Tintoretto, the smallish heads yearning from overmuscled, squarish bodies, the human figure—as in Cain and Abel —a bundle of volcanic torsions. And it is Tintoretto, not Giotto, who in his decorations for the Scuola di San Rocco gives us the carnal immediacy of mysterious emergences, transformations, and manifestations—image after image of agonized greeting. Giacometti, the least devout of men, possessed that sense of life as a suffering toward recognitions of reality which I think is the essence of heroic religious feeling. He believed not in redemption or arrival but in the fully experienced continuity of existence, in the need and desire to return to our imagined source, to the lost garden of perfect recognitions and representations.

1. Giovanni Fattori, Rotonda di Palmieri, 1866.

Oil on wood, 12 × 35 cm (4 3/4 × 13 3/4 inches). Galleria

d'Arte Moderna in the Palazzo Pitti, Florence.

2. Silvestro Lega, The Pergola, 1868.

Oil on canvas, 75 × 93.5 cm (29 1/2 × 36 4/5 inches).

Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

3. Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1920.

Oil on canvas, 30 1/2 × 44 1/2 cm (12 × 17 1/2 inches).

Galleria Comunale d'Arte Moderna

"Giorgio Morandi," Bologna.

4. Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1935.

Oil on canvas, 30 × 60 cm (11 4/5 × 23 3/5 inches).

Private collection, Mestre.

5. Alberto Giacometti, Head of a Man, 1956.

Oil on canvas, 42 × 33 cm (16 1/2 × 13 inches).

Private collection, Switzerland.

6. Henri Matisse, The Rococo Chair, 1946.

Oil on canvas, 92 × 73 cm (36 1/5 × 28 3/4 inches).

Musée Matisse, Nice.

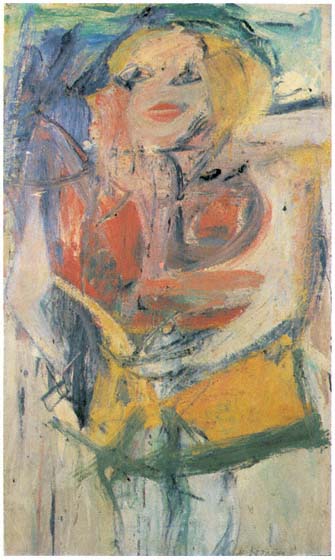

7. Willem de Kooning, Marilyn Monroe, 1954.

Oil on canvas, 50 × 30 inches. Collection of Neuberger

Museum, State University of New York at Purchase, gift

of Roy R. Neuberger (Photo: Steven Sloman).

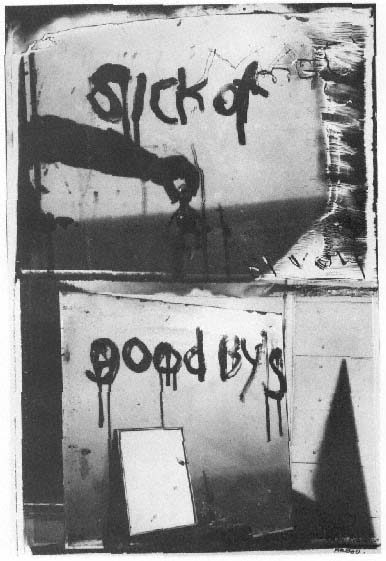

8. Robert Frank, Sick of Goodbys, Mabou 1978.

Copyright 1986: Robert Frank.

Courtesy of Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York.

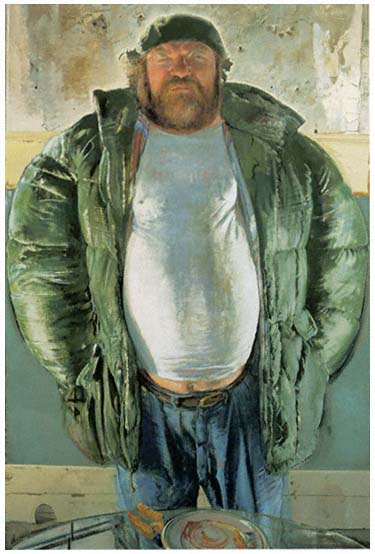

9. Jerome Witkin, Jeff Davies, 1980.

Oil on canvas, 72 × 48 inches. Palmer Museum of Art,

The Pennsylvania State University.

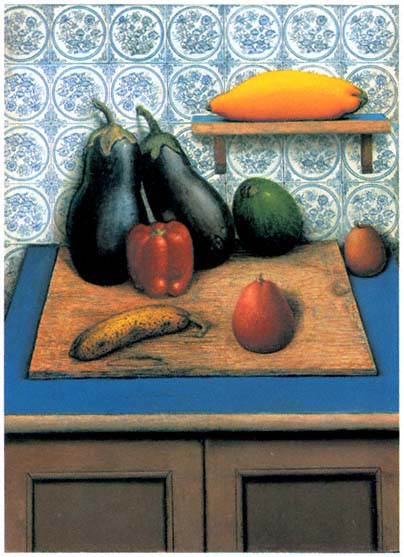

10. Gregory Gillespie, Still Life with Eggplants. 1983.

Mixed media on panel, 41 1/4 × 30 1/8 inches. Private

Collection. Courtesy Forum Gallery, New York.