PART I—

AN ARCHITECTURAL FOOTPRINT ON THE NORTHERN FRONTIER

To understand the churches of New Mexico, one must consider more than the architectural ideas that shaped the form of these structures or the building methods used to construct them. The limits imposed by the physical environment, the patterns of exploration and settlement by the Spanish, and the politics practiced by them as they settled among the Pueblo Indians all contributed to the development of New Mexico's colonial architecture.

Although the churches of New Mexico are rooted in European religious tradition, they are neither completely alien to native soil nor merely provincial variations of European or Mexican church structures because they differ so substantially from their architectural precedents. Rather, the New Mexican church represents the mutual influence or conflation of indigenous American building practices with those of the Iberian Peninsula. The single-naved church with its thick adobe walls, crude structural beams, and transverse clerestory benefited as much from the building traditions of the Pueblo Indians as from the ideas of the Spanish missionaries, military engineers, and civilian builders. Churches in the far northern frontiers differed from high-style churches in Spain and Mexico in part because Franciscan visions and aspirations were constrained by a severe physical environment and limited building technology. In the tension between aspiration and reality resided (and still resides) the source of both the power and beauty of these buildings.

The Setting

Only with the advance of climatic management has architecture been provided the means to distance itself from its immediate environment. For centuries prior to our own, building reflected the impact of the elements on its form, engaging in an exchange between the forces of nature and those of artifice. The needs of individuals and societies also tempered the contour of architecture as habitation acquired concrete form. In time, an architecture balancing these imperatives resulted; in New Mexico the process was no different.

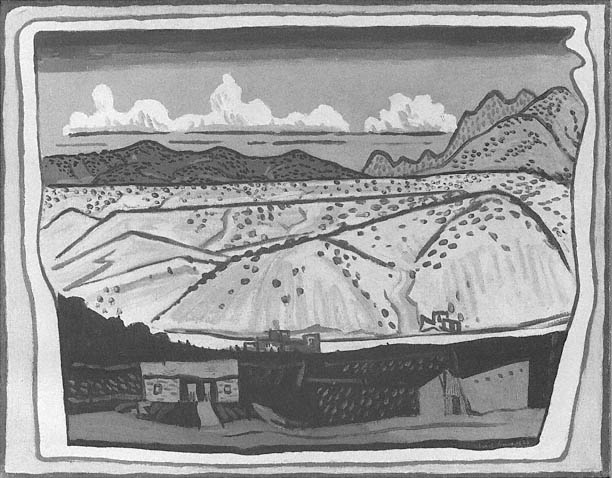

The landscape of New Mexico can stagger with its endlessness [Plate 1]. The land cannot be described as lush in any but a few isolated valleys, and at times desolate is a more appropriate adjective. But even amid the aridity and sparse vegetation there is always the promise of beauty to come: for example, when the cottonwoods are in autumn color or the desert flowers in spring bloom. But the land and the vegetation are only the raw ingredients of New Mexico's landscape. To them must be added

1–1

New Mexican Landscape

Stuart Davis

1923

[Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas]

the desert light. "The high desert plain is a land where distance is lost, and the eye is a liar, a land of ineffable lights and sudden shadows; of polytheism and superstition, where the rattlesnake is a demigod," as Charles Lummis waxed poetically.[1] The chroma of grays, browns, reds, and even blacks of the earth and stone constantly change as the hot, unrelenting light of noon passes into the oblique shadows of approaching sunset. From spring to fall, the sky can be a piercingly clear blue unhampered by reflective dust or refractive moisture. The thunderstorms of summer create fluid skies that layer cloud on cloud, gray on gray continually dissolving like ink on water. Only in winter, when storm clouds obscure the sun, is the bowl of the sky lowered onto the land.

In Sky Determines , Ross Calvin proposed that the aridity of the land endowed the state with its particular character. From the sun, from the desert, came the vegetation and, later, the architecture. Although Calvin's thesis may be too rigidly deterministic, its basic premise is plausible. Nevertheless, the availability of water was only one of the major factors that affected settlement; other environmental conditions also influenced the form that human presence took on the land.

New Mexico occupies a plateau high in elevation, with Santa Fe, the capital, located in the state's northeastern quadrant [Plate 2]. Its ecology is classified as High Sonoran Desert: low in humidity despite the altitude. Elevations above six thousand feet enjoy an annual precipitation of about fourteen inches, a radical contrast to the three inches or less that water the deserts below. The plateau falls sharply just north of the small town of La Bajada (about twenty-five miles south of Santa Fe), and at the foot of this drop lies the pueblo of Cochiti, set against the clearly visible strata of black volcanic rock. Further south, the plain descends an additional several hundred feet as it slopes gradually to Albuquerque and beyond to Las Cruces on the Mexican border.

Cutting across New Mexico from roughly north to south are great ranges of mountains bracketing the fertile river valleys that have sustained both indigenous and colonial settlements. A somewhat milder extension of the Rocky Mountains, the Sangre de Cristo (Blood of Christ) Mountains lie to the east of Santa Fe, isolating the eastern plains from the Rio Grande drainage and peaking at roughly thirteen thousand feet above sea level. The two major gaps in these mountains—the Raton and Glorieta passes—have been strategically important throughout history.

To the northwest of Santa Fe lie the Jemez Mountains, geologic survivors of a massive prehistoric volcanic explosion. The meadows and farms within its caldera contrast sharply with the colors of the desert that surrounds it four thousand feet below. Steep and pine-forested, the source of streams and rivers that eventually drain into the Rio Grande, these mountains form the backdrop to the pueblos of Jemez, Zia, and Santa Ana. The mountains are home to the piñon pine (source of pine nuts) and the scrubby juniper, which rarely grows higher than fifteen feet or so and whose twisted configuration yields little usable wood for major construction. The mountains also provide the tall and straight ponderosa pine used for roof beams, and thus to the mountains the builders went, no matter the distance or the difficulty in transporting the huge logs once they were cut.

Albuquerque is dominated by the hulking backdrop of the Sandia Crest, whose round contour terminates the view of the city when it is approached from the west. Further south the Manzano Mountains turn slightly to the southeast, demarcating the Salinas district, whose dried lakes provided the precious commodity of salt for domestic use and trade. The Salinas district was the site of the missions of Abo, Quarai, and Gran Quivira, known in combination with several smaller settlements—more poetically than accurately—as the "Cities That Died of Fear."[2] The Jicarilla Range beyond marks the southernmost boundary of colonial church building from the beginning of the Spanish settlement to the end of the seventeenth century.

The longest and the largest river in New Mexico, the Rio Grande del Norte is the aorta of the New Mexican landscape [Plate 3]. When the Spanish came upon this river as they moved east from Zuñi, they were aware neither of its source in the mountains of southern Colorado nor of its extent. Broad, yet shallow in its southern parts, the river's majesty increases in the north, culminating in the great Rio Grande gorge south of Taos. Here the deep cut and swiftness of the current suggest the sleeping giant capable of eroding banks and destroying villages. (The river swept away the Santo Domingo church in 1886.) Although always a river of intermittent flow—full and swift during the spring thaw, slow and gentle in late summer—its dimensions today are no longer what they were in the past. Modern water-management systems have significantly modified the Rio Grande: the dam above Cochiti, for example, has reduced the river to a stream during certain times of the year, affecting life along its length. A number of major tributaries feed the river, and

1–2

Landforms

[Adapted from Beck and Haase, Historical Atlas of New Mexico ]

these, too, have fostered settlement. To the north the Chama River provides water to the villages around Abiquiu. Rivers flowing from the Truchas Peak and other nearby mountains sustain the fertile valleys that support the villages of Las Trampas, Chimayo, Cordova, and Santa Cruz. Further south the Jemez drainage serves the pueblos of Jemez, Zia, and Santa Ana before its rivers and streams empty into the Rio Grande.

Roughly paralleling the Rio Grande is the Pecos River drainage, the second major valley system to the east. Here the mountains join the plains, and the sedentary Pueblo Indians were forced to confront the nomadic Plains Indians tribes that included, in time, the Comanche and the Apache. To the west of Albuquerque stretch hundreds of miles of deserts and mesas, a dry landscape of flat-topped landforms that provide the background for the pueblos of Laguna, the Sky City of Acoma, and the Zuñi pueblos near the Arizona state line.

Topography and climate were not the sole determinants of architectural form in New Mexico. They were but two, albeit important ones, of a constellation of factors that included defense, available building materials and technology, and social practices.

The Native Culture

New Mexico's Pueblo story begins in prehistory and centers in two major areas: Mesa Verde in the Four Corners area of what is today Colorado and Chaco Canyon in western New Mexico. These two areas served as home to the Anasazi, the ancestors of the Pueblo peoples. The climate about a thousand years ago is believed to have been more hospitable than it is today; moisture was in greater abundance, and winters were considerably milder. Although a detailed investigation of early Indian settlement and culture is beyond the scope of this book, three points bear directly on the development of the colonial New Mexican church: what the native people built, where they built, and how they built. All had a significant impact on the refinement of Pueblo construction methods during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and these in turn eventually influenced the construction of the Spanish colonial churches.

The first substantial archaeological evidence of construction at Mesa Verde records structures termed pit dwellings that date from about the sixth century. Their basic living space consisted of a shallow pit excavated two to three feet below ground level, above which a wooden superstructure was fashioned, covered first with twigs, and then fin-

1–3

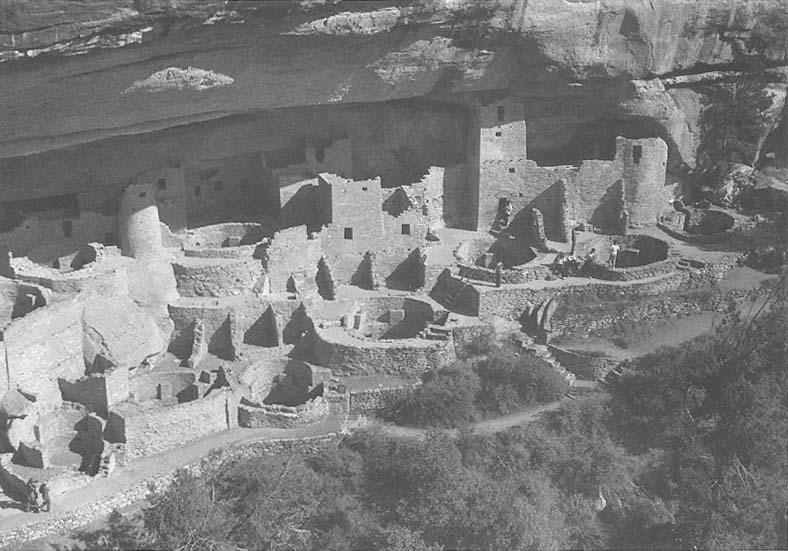

Cliff Palace

Mesa Verde, Colorado

11 – 13th centuries

The conglomeration of cellular units is fitted to the superstructure of the cave.

[1986]

ished in mud. Even though archaeological findings situate some of these dwellings at the base of cliffs, most of them seem to have been built on mesa tops near cultivated plots. The ease of obtaining building ground, defense, and proximity to fields, rather than any geometric organizing principle, governed the arrangement of Anasazi villages.

During the subsequent Development Pueblo period (750–1100), several major changes in construction methods were adopted. Pit construction was abandoned as a house form and was retained only in the underground ceremonial structures called kivas . For domestic use numerous cells constructed of fieldstone were joined in a loose, linear manner to form terraces and defensive structures and to express village identity. It was during this period that clustered building units were first constructed and a sense of collective architectural form emerged.[3]

Sometime during the eleventh century, unascertained forces occasioned a transfer of dwelling sites from the mesa tops to the caves formed by water seepage and wind erosion in the sides of the cliffs. Defense is usually given as the most plausible reason for this shift. Whatever the impetus, it must have been considerable to instigate such a drastic change in living conditions. The cave dwellings were carefully constructed of stone, and because working practices did not allow for refined dressing of the stone, the material was used as it was found. In spite of these limitations, the quality of the craft is impressive even by today's standards. All the walls were laid up dry, or set in adobe mortar, with smaller stone fragments inserted between the larger pieces to ensure stability. The entirety was finished with a layer of mud plaster on both the interior and exterior surfaces. To support the roof, wooden beams spanned the walls to create a structure subsequently covered by wooden crosspieces and a thick layer of mud. The village developed incrementally, with each new room fitted to the existing construction and the superstructure of the cave. The beauty of Mesa Verde architecture derives from the perfect harmony of materials throughout and the soft contrast among the natural contours of the cave, the rectangular forms of the apartments, and the roofs of the round kivas.

In response to a different environmental setting, the Chaco Canyon culture in western New Mexico developed an architecture of a more apparent formal order. Unlike Mesa Verde, there were no large caves for habitation or defense in the Chaco River valley, although the villagers probably had to restrict access to exist. In place of the physical super-

1–4

Pueblo Bonito

Chaco Canyon

12 – 13th centuries

Over a century's time the individual residential and storage units

completed the form of a loose "D ."

[1983]

1–5

Pueblo and Spanish Settlements

[Source: Meinig, Southwest ]

structure provided by the cave to which all construction was secondary, a coherent form emerged from several building phases that required a century to refine. In the case of the multistory Pueblo Bonito, a sweeping D-shaped plan positioned the dwellings and storerooms in a great semicircle that opened toward the river. Like construction at Mesa Verde, the walls of the dwellings were finished with a covering of plaster so that little or none of the exquisite artisanry remained visible. Regardless of whether or not plastering was intended primarily to achieve a sense of architectonic unity, the additional insulation protected the dwellings from wind infiltration and immediate deterioration. In their strength and simplicity the Chaco Canyon structures are impressive. When the refinement of this architectural achievement is set against the barrenness of the surrounding desert and the scarce resources, the stature of the accomplishment increases substantially.

In both these Anasazi culture areas one finds that cellular construction was realized in stone and wood. By piling and agglomeration, whether in response to the cave's aperture or to the surface of the canyon at the lower elevations, the construction method was logical and straightforward. Only trees of limited size were available for construction. A log was cut to estimated length, and if found too long, it was allowed to extend beyond the wall surface even if exposed to rot. Variations of these basic techniques are found in almost all the native groups throughout the Southwest, building practices that not only formed the basis of construction for the succeeding Rio Grande pueblos but also neatly paralleled the methods brought by the Spanish to construct their houses and churches as well.

From 1276 to 1299 Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon suffered a severe drought, which may have prompted the desertion of the mesa about that time. During the ensuing decades a segment of the population emigrated, presumably toward the Rio Grande. Moving eastward, they are believed to have settled with groups of the Chaco peoples in the region around the Pajarito plateau near today's Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, and Frijoles Canyon, now Bandelier National Monument. Although arable land was limited and the proportions of the canyon severely restricted the amount of sunlight that reached the fields, the indigenous settlers were able to utilize the natural caves and the soft volcanic tufa of the hillsides for their homesteads. To increase the volume of their living spaces, they excavated the caves and constructed stone dwellings against the bases of the cliff. Despite the threat of floods and

attack by the Plains Indians, villages were established along the banks of the Rio Grande and other rivers where water flowed year-round, redepositing alluvial soils rich in minerals and fertilizers. When the Spanish arrived in the sixteenth century, they found the pueblos concentrated along the river and its tributaries, although other communities were found to the southeast in the Salinas area and further west at Acoma, Zuñi, and Hopi (located in what is today Arizona).

Exploration

For Spain, the centuries preceding New Mexican settlement in 1598 were charged with the spirit of conquest. After enduring centuries of foreign occupation in Andalusia, the Castillians were able to drive the Moors back to North Africa during the thirteenth century and reestablish Catholicism as the predominant religion throughout the Iberian Peninsula. Quests for the riches of the Orient— spices, silk, and precious minerals—enjoyed some success, as evidenced by Christopher Columbus's 1492 voyage and Europe's "discovery" of the New World. The search for instant wealth, whose perceived reality was heightened by rumor, continued throughout the century and into the next. The risks were great, the stakes were high, the losses were many, and the monetary returns, at times, were incredible.

The uniting of the independent realms of Spain and Portugal in 1581 bolstered the economic resources of the kingdom and made further exploration possible. Throughout the following century, however, fiscal pressures on Spain's treasury continued to mount.[4] A ready source of economic relief could be found in the conquest of the New World. According to popular myth, the vast riches of Indian monarchs lay in Mexico and Peru waiting only to be located, plundered, and finally returned to Spain— to the king, of course—but not without great personal, social, and economic reward for the conqueror. At this time "home, foreign and economic problems were completely intermingled."[5]

Earlier in the fifteenth century, the Catholic nations of Spain and Portugal had announced their intentions to settle and evangelize in the newly explored lands. To reduce potential territorial conflicts, Alexander VI issued a papal bull in 1493 dividing the world more or less into halves, with Spain receiving the majority of the Western Hemisphere. Of equal importance, however, was the pope's grant to the monarch of the right to select the clergy in these lands. As a result, the Spanish aristocracy became thoroughly enmeshed in the ecclesiastical governance of the new colonies. Power was endowed in a series of appointed delegates who ultimately answered to the king. This system did little to eliminate or ameliorate inevitable conflicts of interest between church and civil authorities, problems that continued to plague the government throughout its centuries of administration.

Within three decades after Columbus's landing, Hernán Cortés had conquered most of Mexico and Central America, claiming for Spain the great native populations there as subject peoples. The Spanish turned to the tasks at hand. They extracted the wealth of the land to fill royal coffers denuded by war and recession, established colonies to stabilize control of the lands and ensure a continued flow of revenue to the Iberian state, and attempted to Christianize the native peoples and bring them within the influence of the Catholic church.

The Spanish friars were also compelled by other pressures. The religious fervor of the missionaries was at a peak. The Muslim Reconquest was still fresh in the spirit of the time; one foe of the church had been vanquished and Spain was united again. The second enemy, the Protestant Reformation, would require a struggle extending, at least in architecture and the arts, for almost a century. In painting and sculpture, and not least of all in architecture, the resurgence of religious fervor would propel the rise of an aesthetic that manifested the power of the church.

Shortly after Cortés's conquest, a group of Friars Minor of the Observance, later known as The Twelve, arrived in Mexico to bolster the limited missionary activity.[6] The philosophy that guided the evangelical programs of the mendicant orders operating in Mexico (the Augustinians, the Dominicans, and particularly the Franciscans) was often characterized by an idealism little less than utopian. Bishop Vasco de Quiroga of Michoacán became auditor of New Spain in 1530. Influenced by the humanism of Sir Thomas More's Utopia , Quiroga tried to implement a philosophy that regarded the indigenous people of Mexico as the potential "equals" of the Europeans.[7] In his view, although these natives existed in a lesser stage of development, they were capable of "improvement" and, in time through tutelage, Christianization. With continued exposure to European civilization, they, too, would be capable of leading what he deemed to be full and worthy lives as good Catholics and royal subjects. These questionable intentions were not always fully reflected in the actions of the Spanish clergy and administrators, however.

For the upwardly aspiring Spaniards of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the New World was a place to increase their position or lead a new life. For commoners, it was a road from servitude or debt, although a considerable portion of their remaining years might be required to accomplish any material advancement. Many of the settlers were lured not only by the uncertain promise of wealth but also by the certain attainment of social status; they were to be granted the title of hijosdalgo , "illustrious men of known ancestry."[8] To impoverished nobles, residence in the colonies might help resurrect a family name with glory primed by coin. Settlement was viewed as an investment: extract a reward from the land quickly and leave. This social group constituted a continual nuisance to religious and civil authorities alike because its members usually considered manual labor beneath their station. For all these groups, settlement in Mexico and later in New Mexico was regarded not only as a social experiment but also as a purposeful transplanting of an old culture for both economic and religious gain.[9]

Moving North

By the opening of the sixteenth century, pressures for expansion and the desire for new wealth had lured explorers and missionaries out of central Mexico northward to the barren lands of New Mexico. Myths fueled their quest. The blind pursuit of El Dorado (the tribal chieftain of the Americas who was first covered with vegetal pitch and then dipped in gold dust to create a golden man) and the source of his gold had taken the Spanish throughout South America. He was never found. Further north, it was said, lay the legendary Seven Cities of Cíbola and the land of Quivira—kingdoms of gold, precious stones, and wealth unimaginable.[10]

In due course a preliminary expedition left Mexico in 1539 under the supervision of Fray Marcos de Niza. He was accompanied by a number of Mexican Indians and a Moor named Esteban, who acted as a sort of master guide.[11] The Niza group set out with Esteban preceding the main party as part of an advance patrol, and as they crossed into what is now New Mexico, reports of a settlement reached the main group. The Moor headed toward the villages, convinced of his own invulnerability prompted by his successful escapes from life-threatening situations during his prior journey of survival. The Indians, knowing nothing of his supposed invincibility, proved hostile and dispatched him summarily. His patrol fled, countering its original report of a golden city with news of the skirmish and Esteban's death.

Marcos de Niza approached the village with trepidation and maintained his distance from the settlement. His report to the Spanish authorities confirmed the existence and richness of the Seven Cities of Gold, although he did not specifically write that he had seen them up close. "It appears to be a very beautiful city, the houses are . . . all of stone, with their stories and terraces, and it seemed to me from a hill whence I could view it."[12] The Franciscan's report has prompted much subsequent discussion, particularly because it was instrumental in encouraging the exploration and eventual settlement of New Mexico. Had the friar lied? Had he seen buildings of mud and stone—now generally ascertained to have been part of Zuñi pueblo—at sunset and, so wishing to be convinced of their richness, misconstrued mud for gold? Had the desire for a successful outcome biased his judgment, or had he just been mistaken? The friar had been chosen for his education, reputed powers of observation, and trustworthiness, traits rare among soldiers and colonists. In spite of these precautions, the authorities were misinformed.

Quite possibly, the government had anticipated the content of Fray Marcos de Niza's report, and the image of the cities of Cíbola—now actually seen—fueled the fire of exploration. As a result, a full-fledged expedition set forth during 1540– 1542 under the leadership of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, whose group is credited with the first European sightings of many major features of the American Southwest. Fray Marcos accompanied him. The expedition approximated Niza's prior route in moving north, reaching today's United States–Mexico border near the New Mexico–Arizona state line. Forcing entry into Cíbola, the Spanish found, much to their dismay, nothing to confirm their expectations. In place of gold they found mud; in place of riches, a small agricultural community sustaining its existence with a limited supply of water. The Indians tired quickly of their intrusive guests and enticed the Spanish to move on by telling them of other sightings of the cities of gold, a tactic they would repeatedly use.

The expedition moved past Acoma eastward toward the Rio Grande, where it headed north along the river after stopping in the Galisteo basin on the edge of the Salinas district. Near Sandia pueblo the party established camp, evicting the rightful inhabitants, commandeering their supplies and foodstuffs, and making fitful attempts at religious conversions. With better weather the Spanish headed north once again—always in search of Quivira, the other legendary city of gold—and finally east, entering the

plains of what is now southwestern Kansas. Each time the explorers wore out their welcome, and each time they listened to tales of gold further on, just out of sight, just out of grasp. But Coronado's men had reached their limit. Their lot was miserable; their material gains, nonexistent. Beaten by hardship, the barrenness of the desert, and the extent of the Plains, they retraced their steps, rejoined a splinter group that had explored as far as the Grand Canyon, and headed back to Mexico.

Given the dismal outcome of Coronado's expedition, only a few subsequent attempts were mounted in the following years. In 1581 the joint civil-religious Chamuscado-Rodríguez expedition set out; it added to knowledge of New Mexico but made no major economic or social discoveries. The following year an expedition led by Antonio de Espejo achieved similar results and found slain the two friars left behind by Coronado to proselytize among the Indians. Not until the expedition of Don Juan de Oñate several decades later were serious plans for the settlement of New Mexico entertained.

Colonization

Only in the 1580s was interest in the colonization of New Mexico revived as profitable silver mining in northern Mexico suggested that long-term efforts, rather than quick gains, in New Mexico might prove financially rewarding. In addition was the prospect of thousands of Indians waiting for conversion: people whose existence had been confirmed. As a result, a royal decree of 1583 delegated the viceroy of New Spain to organize the settlement of New Mexico. Considered a politically attractive and potentially lucrative post, the governorship of the new province was actively solicited. The appointment was finally awarded to Don Juan de Oñate of Zacatecas, who provided most of the financial support for the expedition himself and spent three years assembling the necessary supplies, settlers, stock, and permissions.

Even though the lands of the New World were the property of the king, in matters of their administration he was advised by the Council of the Indies, a group composed of humanists, politicians, and religious figures. Articles, later formalized as the Royal Ordinances on Colonization and commonly referred to as the Laws of the Indies, specified in great detail who could and should found colonies, where towns should be sited, where certain buildings should be placed, and so forth. The native peoples were seen as a resource to be protected and educated until ready to enter European culture. In principle the articles, for their time, treated the natives remarkably fairly, proscribing their exploitation or genocide. Article 5, for example, exhorted colonists to "look carefully at the places and ports where it might be possible to build Spanish settlements without damage to the Indian population."[13] Although the articles were imbued with the humanism of the times, they were overly optimistic in their conception of human nature, and their actual implementation often fell short of the spirit that created them.

Royal approval for Oñate's expedition was finally issued in 1598, and he set out accompanied by five Franciscans who had been granted the religious jurisdiction of the new province. New Mexico had been deemed a nullius , a land without the benefit of a bishop or regular clergy, and had been assigned to Franciscan jurisdiction. Oñate more than met the requirements of Article 89 of the revised Laws of the Indies, which governed the requisite numbers of settlers, livestock, and clergy to accompany an expedition. Burdened with thousands of head of cattle and sheep; 400 men, of whom 130 had families;[14] 200 soldiers; and 5 priests in eighty-three wagons, the expedition moved slowly.

Military protection was a necessity not only for the journey but also for the founding of missions. Two to six soldiers were assigned to maintain the religious enterprise, although the friars were often more fearful of the poor example the soldiers might set than of danger from the Indians. Centuries later the problem remained unchanged. Fray Romualdo Vartagena, guardian of the College of Santa Cruz de Querétaro, wrote in a manuscript dated 1772:

What gives these missions their permanency is the aid which they receive from the Catholic arms. Without them pueblos are frequently abandoned, and ministers are murdered by the barbarians. It is seen everyday that in missions where there are not soldiers there is no success, for the Indians, being children of fear, are more strongly appealed to by the glistening of the sword than by the voice of five missionaries. Soldiers are necessary to defend the Indians from the enemy, and to keep an eye on the mission Indians, now to encourage, now to carry news to the nearest presidio [fort] in case of trouble.[15]

That both the presidios and missions were financed from the same source, the War Fund, suggests the basically hostile nature of colonization.

Oñate's expedition followed the most logical highway, the Rio Grande, and entered New Mexico through El Paso del Norte (The Pass to the North, or El Paso, now part of Texas). This route was more direct than the one taken by earlier expeditions;

without the benefit of real roads, travel followed the river valleys, which provided the benefit of a defined path and an assured source of water. From central Mexico northward there were two primary routes separated by hundreds of miles of desert: the Rio Grande drainage in New Mexico and the Gila River drainage in Arizona. Mission systems were founded along both rivers, but contact between these geographic areas was negligible until the arrival of the railroad in the nineteenth century. Like the lands between the two river systems, the Indians who dwelled in them were groups apart.[16] Acoma occupied a fringe of the Rio Grande missions, and pueblos like Zuñi and Hopi were difficult to administer because they lay too far from either jurisdiction. Zuñi, as a result, suffered its lapses of missionary presence, and Hopi was never convincingly brought within the Catholic circle.

As the Oñate group traveled north, it nominally pacified the Pueblo Indians with whom it came in contact and extorted an oath of allegiance to guarantee future obedience. The natives were to acknowledge that there was one God and one king, the former residing in heaven, the latter in Spain. After nearly half a year, the expedition reached what became its destination: the town of Ohke, rechristened San Juan de los Caballeros by the settlers, near the present-day town of Española. Because winter was rapidly approaching and insufficient time remained to build shelter, the Spanish commandeered a segment of the pueblo in which to live. As time and weather permitted, they set about constructing their own dwellings and a crude chapel to serve the entire colony and undertook rudimentary farming. The first church was dedicated in September 1598, although the structure was still incomplete. The Indian residents of San Juan were apparently calm—probably more out of fear than generosity—in tolerating the Spanish incursion.

In late fall 1598, Oñate dispatched a survey expedition of soldiers to explore certain lands to the west, including Acoma. The Spanish were brutally attacked and decimated by the Acoma warriors. In retaliation, Oñate ordered a party headed by Vicente de Zaldívar to avenge these deaths. Zaldívar's men fought their way to the top of the mesa and eventually took the battle, but the bloodshed did not end there. Oñate decreed that all "men over 25 were to have one foot cut off and spend 20 years in personal servitude; young men between the ages of twelve and 25, 20 years of personal servitude; women over twelve, 20 years of personal servitude; 60 young girls to be sent to Mexico City for service in convents, never to see their homeland again."[17] Today this chronicle, although probably exaggerated, still seems particularly severe despite the fact that its perpetrators were desperate to establish a precedent for obedience and control of the native peoples.

Having secured military control of the territory, the Spanish turned to its administration. The encomienda was a central aspect of settlement policy in both Mexico and New Mexico and served as the basis for religious and economic administration when the northern province was colonized.[18] Under the encomienda system, all land was ultimately held by the king, but tracts could be granted in his name to individuals by the royal representative. Together with the land, settlers, friars, or churches could also be assigned as "trustees" (encomenderos ) for one or more Indians. A trustee was "strictly charged by the sovereign, as a condition of his grant, to provide for the protection, the conversion, and the civilization of the natives. In return, he was empowered to exploit their labor, sharing profits with the king."[19] The Spanish thereby encouraged the education of native peoples to the ways of European religion, civilization, and technology but in turn taxed them for the privilege. The encomienda served a military purpose as well. Because the governor was responsible for the protection of the colony, it was to the common good to create a civil militia to augment the scant complement of regular troops. No funds were earmarked for this purpose, but the encomendero could be paid in tribute goods by the Indians he protected. The law specified that goods, not labor, be used as currency, but this was often not the case. In New Mexico "heads of Indian households were required to pay a yearly tribute in corn and blankets to the Spaniards. That put affairs on an orderly basis, since the Pueblo peoples now knew exactly what their obligation was, but it made the burden no more palatable."[20]

The Franciscan, as religious leader, oversaw the spiritual welfare of his charges through the catechism, baptism, and mass. Policy dictated that after conversion individuals could not depart from the church or, once settled in a village, had to remain in residence until the period of encomienda was terminated or the mission was secularized. In some parts of the Spanish New World the encomienda could be hereditary through at least two generations.[21] In others ten years was assumed to be sufficient for the completion of the missionary's work and elevation of the native. But oftentimes ten years was not "sufficient," and the terms were usually extended. His charge seemed not to learn as fast as he should, a colonist might report—not surpris-

1–6

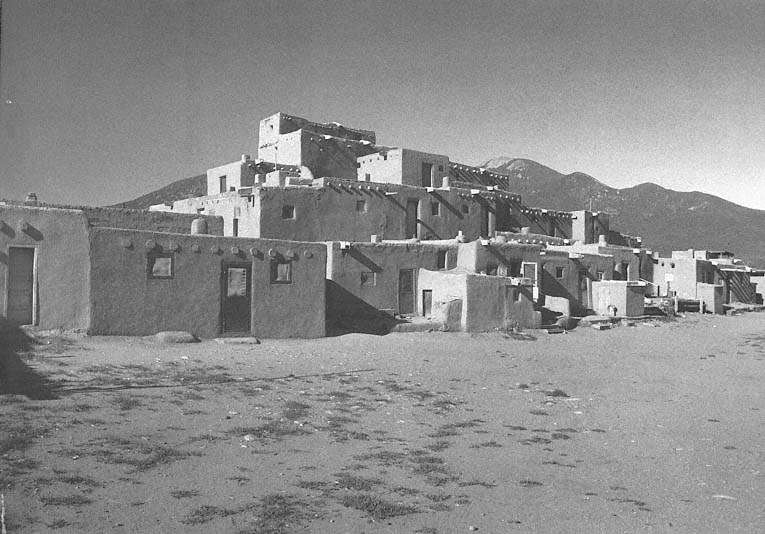

Taos Pueblo

The northern residential block.

[1986]

ing given that Hispanic settlers often exploited the Pueblo peoples mercilessly and treated them as little more than slaves. The imposition of unreasonable burdens left the natives little time to work their own fields, and when the yield was meager, there was hardly enough for the taxes, much less to live on. Attempts to repeal the system in 1542 provoked such a strong reaction by the colonists that modifications were enforced only minimally.

Friction intensified as differences among the various Spanish factions and Governor Oñate solidified. Soldiers and colonists alike were dissatisfied by the limits of Indian productivity and the stringent conditions under which Spanish settlers were forced to live:

They accused the governor of all kinds of crimes and malfeasance. They charged cruelty in sacking Pueblo villages without reason; that he had prevented the raising of corn necessary for the garrison and people and thereby brought on a famine and caused the people to subsist on wild seeds; and insisted that the colony could not possibly succeed unless Oñate was removed. On his part, the governor wrote to the viceroy and the king, charging the friars with various delinquencies and general inefficiency.[22]

To bolster his sagging prestige, Oñate set out in 1604 on an expedition lasting six months; his goal, to find precious metals. In his absence, Oñate's enemies in Mexico increased their advantage. News of the punishment he had meted out, reports of desertion, and the general condition of the colony reflected unfavorably on Oñate in spite of his military accomplishments. His efforts to secure riches for Spain were fruitless. He was ultimately suspended from office in 1607 and subsequently stood trial for indiscretions committed during his tenure.[23]

Conversion Efforts

Eight additional friars arrived in New Mexico in 1600, but within a year two-thirds of them had departed disheartened by the poverty of the land, leaving only a handful of Franciscans to tend the province. The mission effort was tottering in 1608, but at the eleventh hour a report reached Mexico that there were now seven thousand converts, not four hundred, as had been previously reported. The missionary project would continue, and additional Franciscans were dispatched north. Eight years later the churches numbered eleven, with fourteen thousand Indian converts.[24] Although a quota of sixty-six priests had been established for the efforts in New Mexico, it was rarely filled because negative factors usually outweighed religious zeal.

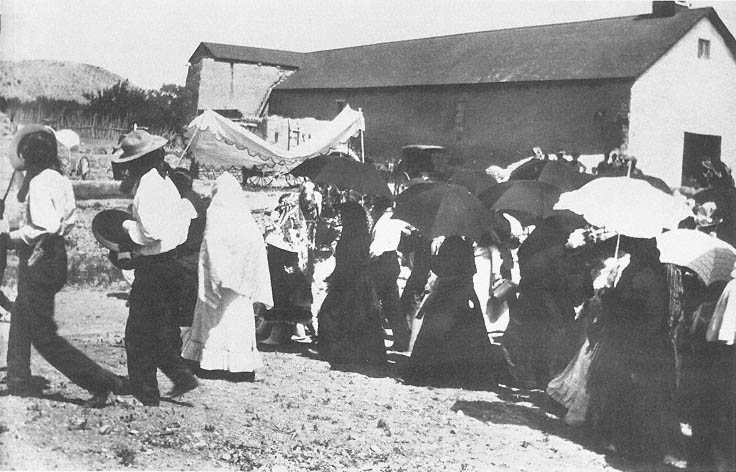

In 1617 Fray Estevan de Perea was chosen as the first custos of the Conversion of Saint Paul;[25] as such, he headed the missionary program in New Mexico. The province was divided into a series of governances, each of which might include several pueblos, and was placed in the custody of friars. They were charged to bring the word of the Catholic God to the heathen, to build a fitting church, and to civilize and improve the material lot of the Indians. Their concerns mixed religious and humanitarian intentions, seen as coincident in Franciscan doctrine.

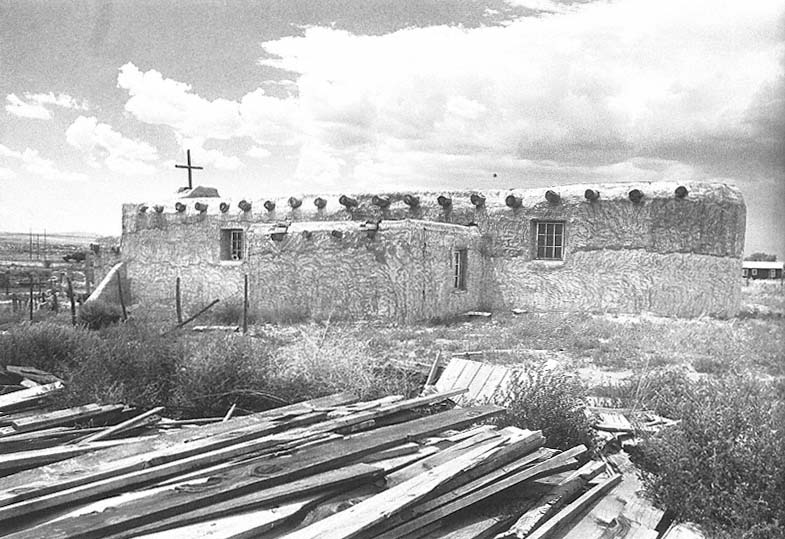

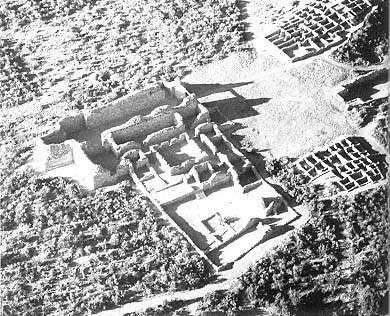

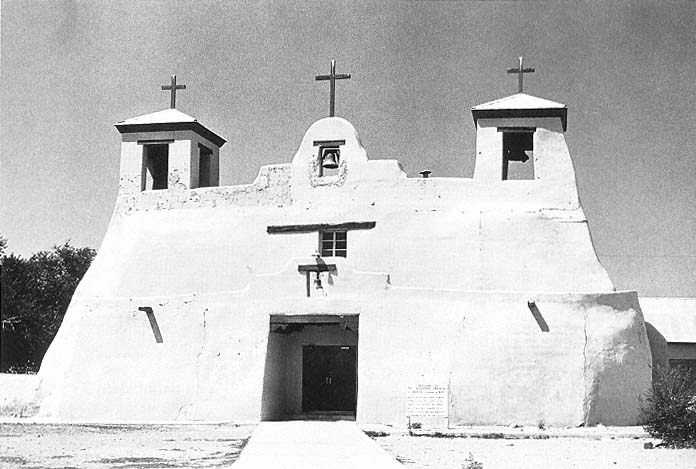

At the close of the 1620s major church structures were being built in the southeastern part of the Salinas district skirting the Manzano Mountains: Abo, Las Humanas (Gran Quivira), and Quarai [Plate 4]. Fray Francisco de Acevedo assumed direction of missionary work in 1629, and the pueblos and their missions were thriving on the edge of the arid plains. Although serving as the first administrative center for this mission group, Pecos proved too distant for effective governance; Salinas was reorganized as its own jurisdiction with Abo as its headquarters.

No less impressive than the structures of the Salinas group was the church of San José de Giusewa in the Jemez Mountains west of Santa Fe, a major stone structure built and abandoned by the 1630s. At Acoma to the west, Fray Jerónimo de Zárate Salmerón assumed his post in 1623; within twenty years a voluminous stone structure had been substantially completed on the most difficult of sites. Along the Rio Grande itself a string of mud-built mission churches of varying sizes and sophistication arose bearing witness to the dedication and determination of the Franciscans. By 1630, according to estimates, twenty-five missions had been sent to ninety pueblos containing sixty thousand Indians.[26]

The friars' efforts were not unqualified successes, however, as they confronted constant resistance to conversion paired with frequent backsliding. Whipping, head shaving, and intimidation by the missionaries undermined their attempts to convert the Indians, and the rotation of the friars precluded any substantive bonds with converts, potential or otherwise.[27] Caught between civilian exploitation of the native peoples and their own religious duties, the Franciscans made no accommodation to the native religion, destroying masks, fetishes, and kivas and forbidding dances. All this in spite of Saint Francis's admonition: "Devotion to an ideal can never be had by repression and reprisal."[28]

From Spain's point of view, the New Mexican enterprise seemed to progress satisfactorily notwith-

standing the difficulties and its distance from central Mexican administration. The standard of living was marginal, but the colony managed to survive. Reports of mass conversions, which often arrived just as the mission program was on the brink of collapse, strengthened flagging interest in this land that offered so little and required so much. When Zárate Salmerón recorded his visit to the province in 1626, he listed all the missions, ranking them as "ordinary," "fair," "good," "very good," "excellent" or "splendid," "handsome," and "most handsome." Acoma was most handsome; Isleta, very fine; and Jemez, splendid.

Four years later, Fray Alonso de Benavides of the Order of Saint Francis, Commissary General of the Indies, provided a description of the mission program that would be a worthy competitor for the claims made by modern advertising:

[The Pueblos] have a notable affection for them [the Franciscans] and for the things of the church which they attend with notable love and devotion. As all the churches and monasteries they have made fully testify. Of all the which it will seem an enchantment to state that sumptuous and beautiful as they are, they were built solely by the women and by the boys and girls of the curacy.[29]

Despite these favorable descriptions of the missions, problems escalated during the 1630s: a governor was murdered although not by Indians, clergy and civil authorities argued over Indian labor, and soldiers at one point occupied Santo Domingo, charging that the pueblo had become a fortress against the governor and the king. The clergy, fearful for their lives, stayed close to the pueblo that served as administrative center for the mission program.

Problems reached crisis proportions. At Jemez Springs the San José de Giusewa mission had to be abandoned around 1630. Pestilence, drought, famine, and attacks by Plains Indians on the eastern pueblos severely undermined their survival. European communicable diseases continually plagued the densely settled pueblos, doubly frightful as an enemy that could neither be seen nor resisted. In 1640 alone, three thousand Indians died of smallpox, 10 percent of the entire population.[30] The Salinas missions, which had been tottering on the edge of disaster since their inception, buckled under various economic and medical pressures and attacks by the Apache and Comanche, who had been granted added mobility by the Spanish importation of the horse. By the end of the 1670s all these missions lay deserted.

Although conditions deteriorated rapidly, the Spanish continued to apply new means to extort production from the Indians. Any fairness that might have been intended under the encomienda system was rarely practiced. The chafing relations between the native peoples and the Europeans increased, as conflicts between the military and the clergy demonstrated to the Pueblo peoples that little unanimity joined the various Spanish factions.

The Pueblo Rebellion

Traditionally, the Pueblo tribes had lived as independent units governed by their own councils. Even among groups that shared the same language, mutual tolerance, rather than political union, was the general practice. But resistance to the Spanish had been building. The colonists' demand for additional fields and pastures at times forced the Indians to relocate, often to land less convenient or less fertile. Late in the 1670s, under the instigation of Popé from San Juan and several other influential leaders from the northern pueblos, the resentment that had been smoldering for a century finally ignited. A native informant recalled:

Popé came down to the pueblo of San Felipe, accompanied by many captains from the pueblos and by other Indians, and ordered the churches burned and holy images broken up and burned. They took possession of everything in the sacristy pertaining to divine worship, and said that they were weary of putting in order, sweeping, heating, and adorning the church; and that they proclaimed both in the said pueblo and in the others that he who should utter the name of Jesus would be killed immediately; and that thereupon they could live contentedly, happy in their freedom, living according to the ancient customs.[31]

On August 10, 1680, the rebellion flared; the Spanish were either killed or forced to flee south to El Paso. Twenty-one Franciscan friars died in or near their churches; four hundred colonists were slaughtered. The Indian victory was swift and complete: the first loss of a Spanish province in the New World.

Life without the Spanish did not prove easy, however, nor was the confederation of pueblos an administrative success. "Scarcely a Pueblo alive in 1680 could remember how affairs had stood before the Spaniards had brought them cattle and sheep, exotic vegetables and grains, iron hardware, and a new religion."[32]

For twelve years the Indians retained control of the country. In 1691 a preliminary expedition attempted to reclaim the province, but this effort proved premature. Finally, however, under the

1–7

Plaza Del Cerro

Chimayo

The best preserved of the fortified plaza town plan.

[Dick Kent, mid-1960s]

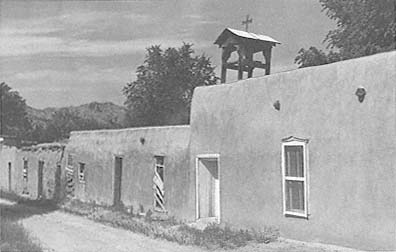

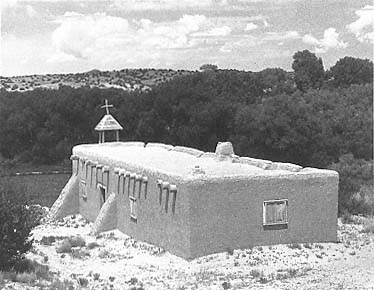

1–8

Ortega Chapel

Plaza del Cerro, Chimayo Only the small wooden belfry identifies this

particular cell as serving a religious function.

[1984]

leadership of Diego de Vargas, New Mexico was retaken during the campaigns of 1692–1693. Given the hostilities of 1680, the Reconquest was swiftly accomplished. Vargas retook the capital in 1693, and Spanish rule was reinstated at the same Palace of the Governors from which the Spanish had fled twelve years before. Relations between the military and the clergy were still strained. In one case, the military purposely provoked the clergy by saying the kachina images (of Pueblo deities) were harmless and allowing the Pueblos to maintain possession of them. This taunting was a familiar practice with a long history. In 1661, for example, one priest recorded "that once when there was a great deal of snow the catazinas (i.e., kachina) Indians went up to the flat roof of the very church and began to perform their superstitious dance very noisily."[33]

During the insurrection, the Indians had in most cases simply torched the roofs of the churches, as if this act alone were enough to deconsecrate these buildings and remove them from the Christian province. Laying adobe walls was time consuming, and if they were still standing, why not use them to good purpose: as a corral, for example? With the Spanish return, the church walls were repaired or rebuilt, and new roofs were constructed. The Pueblo Revolt marked a turning point in the history of virtually every existing church structure in New Mexico, thereby making problematic questions of origins, dating, and formal evolution.

In 1696 a second revolt flared but was quickly quelled. For the most part the colony—both Spanish and Indian alike—settled thereafter into maintaining its existence. Bishop Pedro Tamarón y Romeral undertook an inspection in 1760 and was appalled at the state of both clergy and religion in the province. Sixteen years later, Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante made a two-thousand-mile voyage of exploration and investigation. As an official visitor , Domínguez left an excruciatingly detailed description of mission architecture and native ethnography; his inventory of even the smallest object suggests the paucity of the missionary program in general and church holdings in particular. Domínguez's Description of New Mexico provides an invaluable document for examining the state and use of the churches of the province at the end of the eighteenth century.

Almost from the very beginning, the regular church had continually attempted to wrest control of the New Mexican religious project from the Franciscans, who had been granted its jurisdiction. Finally in 1797, under renewed pressure from the bishop of Durango, the towns of Santa Fe, Santa Cruz, and Albuquerque were secularized, which placed the churches under the direction of parish priests rather than Franciscan missionaries.

Spanish Town Planning

At the time of the initial Spanish entrada into New Mexico, the Pueblo Indians already occupied most of the rich river drainage lands, such as the Rio Grande and the basins of the Chama, Pecos, and Galisteo rivers, which were fertile with organic matter eroded by the rivers near their origins and redeposited along their banks. The rivers also guaranteed the steady supply of water necessary to make the land viable. Because the Europeans shared with the Pueblo Indians a need for productive soil, Spanish colonies often overlaid native settlements, forcing the indigenous peoples to shift location by pushing them on or by circumscribing the lands surrounding the pueblos. Although a proscription against this kind of incursion was included in the Royal Ordinances on Colonization (the king declared his concern for the well-being of all his citizens, including those of non-Hispanic origin), disputes arose constantly as the fight over arable land continued without conclusive resolution.

Defense against a mutual enemy, the Plains Indians, encouraged an uneasy alliance between the Spanish and the Pueblo tribes. Unlike the Pueblo peoples, Hispanic settlers displayed a distinct preference for living next to their fields in scattered ranches, even though this left them particularly vulnerable to Apache, Comanche, or Navajo attack. When danger threatened, they were forced to flee or to live within the pueblo until the threat subsided. While uncomfortable with the alien presence, the Pueblo peoples were at least grudgingly grateful for the security offered by European arms. In any event, they were offered very little choice in the matter.

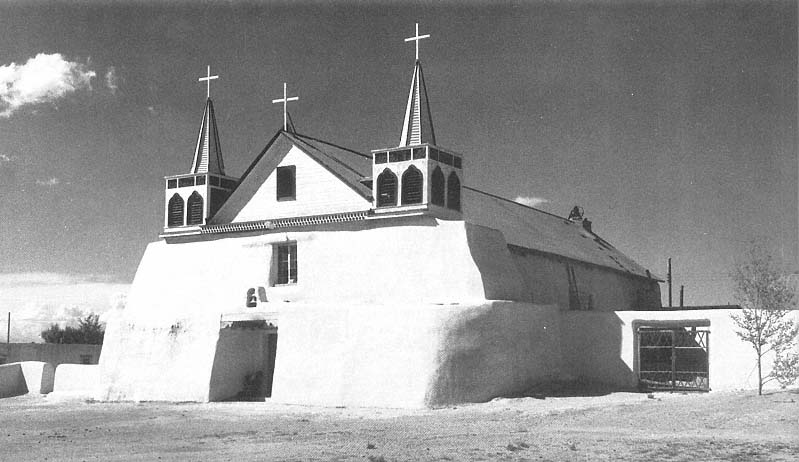

To withstand the hit-and-run tactics of Indian incursions, settlements were developed on the model of the plaza , a word that can be loosely translated in English as "fortified village."[34] Consisting of a continuous perimeter of thick-walled adobe buildings, the plaza presented an almost unbroken exterior surface. At Las Trampas and Ranchos de Taos, vestiges of the plaza remain and suggest that the church was built pragmatically as a part of the circumferential wall to reduce the total volume of construction. The best-preserved example of the type is found at the Plaza del Cerro at Chimayo (founded about 1730, heavily restored in this century) northeast of Española. Here the structures for dwelling

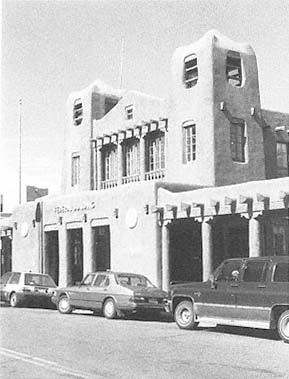

1–9

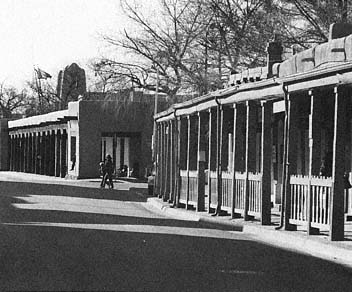

Central Santa Fe

The plaza occupies the area in the center of the photo; the Cathedral

of Saint Francis is above and to the left; the Palace of the Governors

lies to the lower left.

[Paul Logsdon, 1980s]

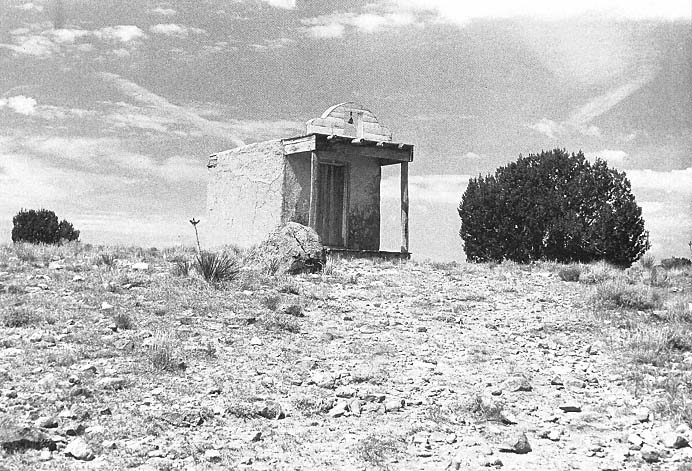

and utility adjoin along the perimeter, and almost all of them, even today, expose few openings to the countryside. The enclosed land offered limited areas for gardening and grazing, a problem aggravated by the limited availability of water to those who sought refuge within the walls of the plaza during times of threat. The plan of the plaza as a whole was more important than any single building, and there was little adjustment of building form for any particular use. (On the west side of the plaza, for example, the small private Ortega chapel of San Buenaventura is distinguished from the houses and utility structures of the plaza only by a cross and a small wooden turret on its roof.) The plaza was a more generic and less formally conceived type of town layout. The only true architecturally planned communities in New Mexico were the villas , or chartered municipalities, the foremost settlements in the territory.

In 1599–1600 the Spanish moved into the town of Yunque (also Yungue or Yunge) on the bank of the Rio Grande and established the first de facto capital of New Mexico at San Gabriel.[35] Lying far to the north, San Gabriel was soon deemed to be an ineffective administrative center because the Rio Grande pueblos extended from Taos in the north to near Socorro in the south, with spurs to the southeastern Salinas district and westward to Acoma and Zuñi. The capital was relocated for expediency in 1610 to what is now Santa Fe. Although not directly on the Rio Grande—which was a distinct disadvantage for agriculture—the site was otherwise well suited for settlement. Its average rainfall far exceeded that of the lower elevations, and the new site was more centrally located in relation to the string of native communities along the river.

As early as 1513 various ordinances governing a wide range of details regarding colonization had been issued; these were formalized by Philip II in 1573 as the Laws of the Indies. Although they were intended to cover virtually every aspect of colonization, the impact of these directives diminished with distance from Mexico City, and in New Mexico their dicta were often only weakly applied. Santa Fe, however, remains one of the few cities in the United States that clearly bear the stamp of these codes even today. The city, as envisioned in the Laws of the Indies, was to be rational in design and yet possess and express symbolic and ceremonial attributes. The conception of urban form embodied in the articles was derived from Renaissance humanism and was a response to the medieval city's dual problems of crowding and civil strife, both the results of uncontrolled and convoluted incremental

growth. To some degree the prescribed city plans were based on cross-axial grids similar to those of the Roman city, with its cardo (north-south) and decumanus (east-west) streets. Each subsequent revision of the planning ordinances after 1513 more closely emulated the rectilinearity, if not the precise layout, of the Roman model.[36] Also, the reintroduction of the grid in Spanish Renaissance thought probably revealed the influence of the architect and theorist Leon Battista Alberti's noted architectural treatise De re aedificatoria (Ten Books on Architecture, 1485 or 1486), which circulated widely in learned circles. Alberti, in turn, had drawn on the Roman Vitruvius, an architect who also influenced sixteenth-century Mexican architecture, as a major source of information and inspiration.[37]

Although Renaissance humanism is usually identified as the motivating force for the use of the grid plan throughout Spanish America, a direct connection with European practice has been lacking, even though the bastides of southern France and siege towns in Spain were both planned on the grid system and resembled settlements built in accord with the Laws of the Indies. George Kubler recently demonstrated, however, that towns constructed in France between Grasse and Nice to repopulate the countryside during the early sixteenth century were just such a connection. Previously abandoned during the plague years of the fourteenth century, new towns such as Valbonne (1509) and Vallauris (1501)—both of which were developed by the Benedictine abbey of Saint Honorat of Lérins—were planned without walls but with contiguous dwellings forming a defined perimeter. Valbonne in particular resembles an enlarged version of a New Mexican fortified village such as Chimayo, subdivided using an orthogonal geometry with the plaza near its center.[38]

The Laws of the Indies also prescribed the location and site of the town by, for example, specifying on which shore of a river the city should be built for defense or commerce and how to ascertain the quality of the land:

The health of the area which will be known from the abundance of old men or of young men of good complexion, natural fitness and color, and without illness; and in the abundance of healthy animals of sufficient size, and of healthy fruits and fields where no toxic and noxious things are grown, but that it be of good climate, the sky clear and benign, the air pure and soft, without impediment or alterations and of good temperature, without excessive heat or cold, and having to decide, it is better that it be cold.[39]

Colonists were urged to settle "in fertile areas with

1–10

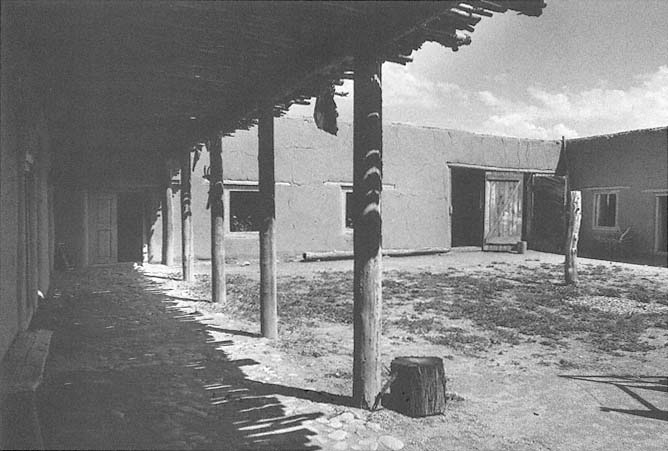

East Palace Street

Santa Fe

The arcades of Sena Plaza and the Palace of the Governors suggest

the character of the capital's streets during the late nineteenth

century.

[1981]

an abundance of fruits and fields, of good land to plant and harvest, of grasslands to grow livestock, of mountains and forests of wood and building materials for homes and edifices, and of good and plentiful water supply for drinking and irrigation."[40]

The ceremonial heart of the town was the plaza mayor , the principal open space. Less a square or a promenade than a campus martius on which the military could train and parade, the main plaza was "to be the starting point for the town. . . . The Plaza should be square or rectangular, in which case it should have at least one and one half times its width for length inasmuch as this shape is best for fiestas in which horses are used and for any other fiesta that should be held."[41] Moreover, "the size of the plaza shall be proportioned to the number of inhabitants. [The plaza] shall be not less than two hundred feet wide and three hundred feet long and five hundred and thirty-two feet wide. A good proportion is six hundred feet long and four hundred wide."[42] Fronting the north side of the plaza was the Palacio Real, or Palace of the Governors, a site the building still occupies in Santa Fe.[43]

Curiously, the principal religious edifice was to be built, not squarely on the main plaza, but to one side—apparently to provide greater prominence. "The temple in inland places shall not be placed on the square but at a distance and shall be separated from any other building or from adjoining buildings; and ought to be seen from all sides so it can be decorated better, thus acquiring more authority."[44] "For temples of the principal church, parish, or monastery, there shall be assigned specific lots. . . . These shall be a complete block so as to avoid having other buildings nearby."[45] The predecessor of today's Cathedral of Saint Francis in Santa Fe, the Parroquia (parish church) occupied a site in accord with this directive. It should be noted, however, that the plaza originally encompassed twice its current area and that the block today bounded by East Palace Avenue, Federal Drive, and East San Francisco Street was originally part of the plaza before it was displaced by commercial construction during the nineteenth century.[46]

The cathedral thus originally occupied a position of only secondary importance on one corner of the plaza. Prominence and centrality were instead granted to the Palace of the Governors, the administrative center and residence of the king's representative in the colony. Although the relative position of church and state on the plaza of Santa Fe might strike us today as curious, the urban form embodied implicit attitudes about their respective positions in the provincial capital. In spite of the tone and intermittent specificity of the planning ordinances, they were ultimately ambiguous and open to interpretation, and their literal application was only very rarely the case in New Mexico.

Extending from the political, social, and commercial heart of the town were streets arranged in a rectangular grid. Article 114 proclaimed that "from the plaza shall begin four principal streets," and Article 115 announced that "around the plaza as well as along the four principal streets which begin there, there shall be arcades, for these are of considerable convenience to the merchants who generally gather there." Indeed, native merchants continue to trade in the arcade of the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe today. The Laws of the Indies also described other characteristics of the ideal city and warned that unhealthy but necessary services, such as fisheries, slaughterhouses, and tanneries, should be positioned so "that the filth can be easily disposed of."[47] The town should have a commons, and sites for houses and shops were to be distributed by lottery, although no lots on the plaza were to be given to "private individuals."[48] Once assigned, the inhabitants were admonished that "each house in particular shall be built that they may keep therein their horses and work animals, and shall have yards and corrals as large as possible for health and cleanliness."[49] In spite of the careful planning of the city and in spite of its status as provincial capital, Santa Fe was characterized in the late eighteenth century by Domínguez as "lack[ing] everything. . . . The Villa of Santa Fe (for the most part) consists of many scattered ranchos at various distances from one another, with no plan to their location."[50]

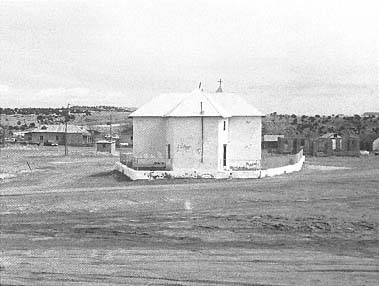

After the Reconquest of 1692–1693, Governor Vargas was forced to find new land to accommodate sixty-six families that had recently emigrated to northern New Mexico. One must assume, however, that the limited tracts of arable land surrounding the capital, rather than any actual dearth of building sites, caused the founding or refounding of the second villa, Santa Cruz. Reduced today to a dusty field of intersecting roads, Santa Cruz retains even less of its original plaza than does Santa Fe. Perhaps buildings never fully enclosed the space, although an 1848 sketch plan suggests a dense, contiguous architectural fabric. The definition of the plaza in an architectonic sense is minimal, and to the great bulk of the church of Santa Cruz falls the task of marking the center of a densely built town that no longer exists.

The third of the charted municipalities, Albuquerque, was founded in 1706 and still possesses a neat plaza whose style, like that of the church of

1–11

Severino Martínez House

Taos, circa 1804

The house as protection from the enemy and the elements, with stout adobe walls, few openings, and internal courtyards.

[1986]

1–12

Farmhouse From Mora

Reerected at Las Golondrinas Folk Museum, La Cienaga

The interior of the house was developed as a linear

arrangement of rooms; the pedimented doorways and

painted wall decoration are characteristic of northern

New Mexico.

[1984]

San Felipe Neri on its north side, was anglicized late in the nineteenth century. The vast expansion of the city in the postwar years and the unfortunate development of Old Town Albuquerque as a tourist attraction during the last decade or two have undermined the calm dignity amid dust that characterized the earlier plazas. Beneath the surface, however, the skeleton of the original plaza and the diluted directives of the Laws of the Indies can still be ascertained.

The Hispanic Dwelling

The idea of a rectangular space enclosed by walls or buildings pervaded Spanish colonial construction from house to church to city. In settlements the idea manifested as the fortified plaza town or the plaza mayor of the city. In the house or on the ranch, the placita , or "courtyard," was the configuration basic to all but the simplest dwellings, and it shared certain affinities with the convento of the church and the church building itself. In their construction and plan the house and the church complex displayed a common sensibility, if a somewhat different form. Thus, an examination of both Spanish and native dwellings provides a foundation for understanding the planning of the more monumental religious architecture of New Mexico.

The Hispanic New Mexican house, as Bainbridge Bunting showed, shared formal similarities with native dwellings, although it sometimes differed in configuration or detail.[51] The house was usually of simple construction: rooms of rectangular mud blocks with a few window openings and a door. Joined in a linear fashion, rooms extended along the longitudinal axis of the house; the width of the house—like the nave of the church—was often determined by the length of the trees available to make the beams. The layout could take landform and use into account, bending where necessary to better accommodate the builder's wishes or the topography. When land was plentiful the house remained a single story; only in the later nineteenth century did the pressures of limited land availability in cities encourage multistory structures. This building pattern of single-story dispersed housing stood in marked contrast to the stacked blocks of Indian pueblos, such as those at Pecos, Zuñi, and Taos, built before contact with the Spanish.[52]

Thick-walled structures address the hot and dry climate of the desert by storing or delaying the transmission of heat (a property known as thermal mass). Heat transfer works this way: the thick walls cool during the night. Throughout the day the

1–13

Severino Martínez House, the West Courtyard

[1986]

1–14

Severino Martínez House, Plan

An example of the double courtyard plan: one for human dwelling and

one for work, storage, and animals.

[Source: Plan by Jerome Milord, 1985]

walls, particularly those facing south and west, receive considerable radiant heat from sunlight, which is absorbed by the adobe. But some time is required for this heat to penetrate through the wall mass. All throughout the cool night the heat in the walls radiates into the room, keeping it warm, until by morning the heat has dissipated and the cycle begins anew, with the room remaining cool throughout the day. The system, of course, never works perfectly, but it explains the performance of thick-walled buildings in a hot and dry climate and the thermal characteristics of the interior spaces of houses, churches, and conventos.

In time the thermal advantages of thick walls were augmented by the addition of arcades, which shielded the south and west walls from solar heat buildup. The function of the portal , or arcade, in Hispanic architecture thus roughly paralleled the stick frameworks, or ramadas , of Pueblo building: shaded, ventilated areas under which the Indians sat or worked and on which they dried vegetables, fruits, and grains. In fact, the Pueblo tribes lived out of doors much of the time, on the roof terraces of the stacked dwellings or on the ground. Their architecture also revealed an understanding of thermal performance. Dwellings constructed in compact units, with only narrow pathways between adjacent structures, shaded the opposite building, thereby reducing the direct heat gain. Conversely, stepping the pueblo's form toward the south guaranteed greater solar collection during the winter months. Although many of the pueblos illustrated both these general tendencies, certain aspects of this climate management might have been circumstantial, rather than intentional, and in any event were not the sole parameters directing building.[53]

The linear bar, growing by accretion to accommodate the family's needs, was also a common residential configuration. As the dwelling grew, the string of rooms bent around an enclosed placita, thereby limiting the exterior openings to one or a few while increasing the structure's defensibility. The dwelling spaces and perhaps storage or work areas occupied one side of the courtyard, which shared the intimate internal orientation of Muslim domestic architecture. A covered passage, called a zaguán , permitted entry to the interior courtyard, and depending on its size, the zaguán could double as a wagon entrance, a breezeway, or a work area.[54] Larger ranches might also include a chapel, a barn for the animals, and even a torreón (fortified tower), a defensive stronghold and observation point. Built of adobe or stone, the upper floor was used for reconnaissance and shooting, the lower to store water and provisions and house women and children during attack.[55] When necessary, the court itself could serve as a corral.

More complex building groups could be organized on the double courtyard configuration, which separated the inhabitants from the animals by providing one human and one agricultural court. This planning arrangement was also used in building the convento, or friary, that accompanied each mission. As a plan type, the convento was more a farm or ranch abutting a church than a monastic cloister. Its concerns were more functional than ceremonial or spiritual; its form was secular, not sacred, although the nave of the church itself often contributed one side to the square court.

Unlike the later California missions, which were almost always formed in a quadrangle, the New Mexican church complex was more haphazard in its planning and more ad hoc in its adjustment to prevailing conditions. The New Mexican church also frequently served less of an economic role in the community than did the mission among the seminomadic Indians of the West Coast. In New Mexico the religious institution was forced to acknowledge the society and buildings of a sedentary culture and to adapt to the existing structure of the pueblos, rather than to create a new town, as was the case in California.

The ornamental courtyard garden of the California mission never developed in New Mexico: water was too precious for purely ornamental purposes, and most priests had enough difficulty raising their own food, much less time to pursue the decorative. If there were ornamental plants, they were probably grown in ceramic pots.[56] Because the pueblos in New Mexico were scattered and priests were few in number, friars usually lived alone. The pattern of the cloister or monastery was thus inappropriate—although there was always a lingering image of what the Franciscan monastic home in Mexico had been. And a century and a half separated the evangelical campaigns of Franciscan New Mexico and California. By the late eighteenth century the purposes and models of conversion had been significantly altered by the impact of Jesuit thought, instigating a consequent shift in architectural response.[57]

Church Patterns

When the missionaries began evangelical work in Mexico in the early 1500s, they carried with them the architectural prototypes of the churches of Spain. The centuries of Moorish occupation had precipitated there the development of fortified religious

architecture, particularly in those areas of southern Spain in proximity to the lands of the "infidels." Even though the traditions of Spanish Romanesque and Gothic architecture continued in the New World, military uncertainty caused their modification. Walls were thick, penetrated by few openings, and buttressed by masonry piers. According to George Kubler and Martin Soria:

The massing of mid-century [sixteenth] churches suggests military architecture. The bare surfaces of massive walls were a necessary result of untrained labor and of amateur design. Furthermore the friars needed a refuge, both for themselves, as outnumbered strangers surrounded by potentially hostile Indians, and for their villagers, who were exposed, especially on the western and northern frontiers, to the attacks of nomad Chichimec tribes after 1550.[58]

In their simplicity, their single nave, and the relation of the convento to the church, the monastic churches neatly presaged the later religious sanctuaries erected in New Mexico.

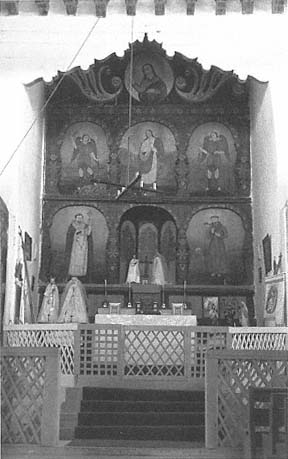

Vestiges of these prior concerns remained in Mexican church architecture into the seventeenth century, but their prominence was undermined by an expenditure of accumulating wealth and the exuberance of the baroque attitude toward form and space that countered the Protestant Reformation. Splendor and light became the foremost vehicles for reasserting the power of the church, and an enthusiasm for architecture paralleled religious ecstasy. The single-naved church, perhaps extended by transepts, served as the basic form in Andalusia and later in the New World; but with the development of a facility in central Mexico for working stone, an elaboration in both size and complexity followed suit.

Early builders restricted areas of ornamentation to the facade, doors, and window surrounds. With the ultrabaroque, however, the ornamental field exploded.[59] Decoration focused the celebrants' attention on the facade and the altar. At the extreme, the building's mass merged with its ornamentation and virtually dissolved in luminous illusion. The physical limits of the space admitted no visual bounds, and the light that flooded through cupolas and lanterns dramatically illuminated the theater of belief. In some New World colonies, this extremity of architectural expression waited for decades, if not centuries, to achieve a near parity with the churches of the homeland. In certain Mexican churches, in contrast, the architectural exuberance at times surpassed that of contemporary Spain. In New Mexico, to the contrary, exuberance never really arrived.

The native building technology of the sixteenth century was limited primarily to stone implements; the vast majority of tools and ironware needed to construct the new churches was imported by Europeans. At first churches were small, particularly the rural missions set in the mountain country or jungles of Mexico.[60]

As late as the close of the sixteenth century, decades after the Conquest of Mexico, these outlying churches remained simple affairs: single rectangular halls with neither the transepts nor side aisles common to the Romanesque or Gothic religious architecture of Spain. Built of stone, mud, or a combination of the two, the churches employed wooden beams, rather than masonry vaults, to support the roof.

Even in the most isolated areas the church grew correspondingly with the size of the community, and for these rural missions the church and the village were nearly synonymous. Building came under the priest's supervision, and he no doubt based his plans on memories of Spanish or central Mexican ecclesiastical prototypes. Military engineers or civilian builders probably contributed critical construction expertise. In one documented instance, Padre Nicolás Durán brought to Lima a scale architectural model of the Casa Professa in Rome to serve as an object lesson for Peruvian religious architecture.[61] Few records of such formalized transmission of architectural ideas as this one remain, however, and by the mid-sixteenth century Mexico was producing noteworthy architecture by resident designers.[62] The sophistication of an architectural idea and its methods of realization varied with the period and the place in which the church was built.

In Peruvian towns, architecture developed from the beamed, single-nave structure of the vaulted form more reminiscent of the Iberian Peninsula. At times the vaults were more ornamental than structural, built of plaster over wooden lath rather than carefully fitted stone. In the hinterland, however, in mountain districts such as those around Lake Titicaca, vestiges of the primitive church remained, the closest parallel forms to those of the religious architecture of early New Mexico. And like the New Mexican churches, these buildings were tempered by necessity in their isolated locations; their fabrics avoided the elaborate formal play of urban religious architecture and more directly addressed the exigencies of their sites and religious programs.

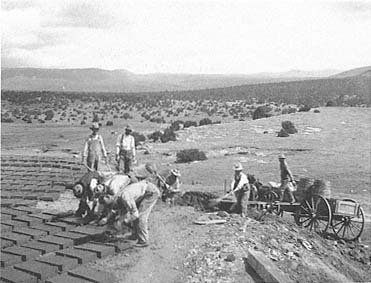

The combination of the reducción and the tremendous number of rapid conversions exerted insistent pressures on both the clergy and the physical fabric of their churches. As a result, hundreds or perhaps even thousands of new or would-be Chris-

1–15

Hypothetical Plan of a New Mexican Church

with Transepts

tians waiting to receive conversion required religious accommodation. Because the diminutive church structures allowed by rural construction methods could not embrace all these converts, a new form of open-air chapel known as the atrio was developed to serve this purpose.

Even though it was common practice to enter the Hispanic church through a walled burial ground called the campo santo , the conversion of this enclosed but unroofed space to ceremonial use was a Mexican contribution. This development was not wholly without precedent, however. Faced with similar programmatic demands, the churches of early Christiandom and many of the great pilgrimage churches of Europe had included an outdoor altar from which mass could be celebrated. But the adaptation of the sanctuary's form to strengthen the prominence of the entry and the slight reorientation of the focus of the church toward the atrio represented a development of historical precedent.

Although permitted to enter the cemetery, Indians were forbidden to enter the church until they had successfully completed catechism. Certain devotions were performed by the priests on the front steps of the church, however, the congregation having gathered within the walled enclosure of the campo santo. In time a rudimentary chapel directed toward the exterior was integrated into the front or side of the church to accommodate these new uses.[63]