Chapter One—

Surviving the Reformation

By his own reckoning, the most important accomplishment in Samuel Clemens's life was his successful courtship of Olivia Langdon. In many ways he seems to have regarded it as his most surprising accomplishment as well. More than a year before he met her, and more than two years before it occurred to him to fall in love with her, he wrote his old Hannibal friend Will Bowen about his persistent bachelorhood. "Marry be d———d," he said. "I am too old to marry. I am nearly 31. I have got gray hairs in my head. Women appear to like me, but d———m them, they don't love me" (25 August 1866). He had definite ideas on the subject, however, ideas that in a general way reflected the Victorianism of his time and the latent Calvinism of his upbringing, ideas that were often at odds with the vagabond adventurer's life he had chosen. Marriage was a static, settled condition; it was also expensive, hallowed, and at virtually every turn informed by a bewildering degree of earnestness.[1]

By contrast, Clemens had spent about half of his thirty-one years unfettered and in motion, having left home at seventeen to see the world and take his chances in it. From the West, where he spent five of those vagabond years, he wrote his mother and sister, "I always intend to be so situated (unless I marry,) that I can 'pull up stakes' and clear out whenever I feel like it" (25 October 1861). A few months later he shared with his sister-in-law his notions regarding the contrast between his behavior as a bachelor and his expectations as a husband. "I never will marry," he told her, "until I can afford to have servants enough to leave my wife in the position

for which I designed her, viz:—as a companion . I don't want to sleep with a three-fold Being who is cook, chambermaid and washer-woman all in one. I don't mind sleeping with female servants as long as I am a bachelor—by no means—but after I marry, that sort of thing will be 'played out,' you know" (29–31 January 1862). Such a view contributed powerfully to the likelihood that under almost any circumstances courtship and marriage would require major changes in Clemens's outlook, habits, deportment, and, he was quite sure, in his character. By ultimately pinning his hopes on Olivia Langdon, a woman whom he took few pains to distinguish from the angels, he raised the ante on change considerably, at least in his own mind, and in so doing sentenced himself to nothing short of thorough, relentless reformation.

"If I were settled I would quit all nonsense & swindle some girl into marrying me," Clemens wrote Mary Mason Fairbanks. "But I wouldn't expect to be 'worthy ' of her. I wouldn't have a girl that I was worthy of. She wouldn't do. She wouldn't be respectable enough." The letter was written on 12 December 1867, just fifteen days before he met Olivia Langdon, the woman he would in fact marry a little more than two years later. During those two years, at first with Mary Fairbanks's finger wagging at him in their correspondence, and then with his idealization of Olivia to encourage him, Clemens gamely undertook a personal reconstruction that was intended to make him a conventionally "better" individual—more religious, more regular in his habits, more refined, more comprehensively civilized. But if Sam Clemens grew up, got religion, and became respectable, what would become of Mark Twain? How does a man who believes and hopes that he has sown the last of his wild oats preserve the vitality of a character who has risen to national prominence in large part by portraying himself as a heedless and irreverent vagabond?

Clemens was as a matter of fact determined to "improve," to become more conventionally respectable, before he met Olivia Langdon in December 1867. During the Quaker City voyage that began in June of that year, perhaps at the urging of Mary Fairbanks and others, he resolved that the time had come to purge both his life and his writing of their coarseness. This is not to say, as he himself sometimes implied, that he was at the time merely an ignorant vulgarian, but rather that he became increasingly self-conscious

Mary Mason Fairbanks. (Courtesy Mark Twain

Papers, The Bancroft Library)

about what he considered his own limitations and those of the prevailing western humorists as he grew more successful. Because of that self-consciousness, he was perhaps ready, even eager, to come under the jurisdiction of a good-hearted and domineering matron—a more formidable Widow Douglas—by the time the Quaker City set sail.[2] With Mary Fairbanks just as eagerly playing the part of "Mother," what might be called the comic phase of Clemens's reformation had begun.

Both mother and "cub" were able to regard their roles in this

comedy humorously and even ironically. There was room in the relationship for teasing and posturing, strategies which kept the reforming process alive and made it fun for the players. The mother, at thirty-nine, was neither as venerable nor as officiously censorious as she sometimes pretended to be; the cub, at thirty-one, was not as young, or as uncomprehending, or as hopeless as he let on. But the game, like almost all games in Clemens's life and work, had a serious dimension, and he was determined that the comedy would continue happily, with the elevation of its hero to a higher station in life. His very first letter to Mother Fairbanks, written on 2 December 1867, two weeks after the Quaker City voyage had come to an end, illustrates the mix of playful exaggeration and sincerity that characterized his attitude toward the improvement she promoted in him:

I was the worst swearer, & the most reckless, that sailed out of New York in the Quaker City.... I shamed the very fo' castle watches, I think. But I am as perfectly & as permanently cured of the habit as I am of chewing tobacco. Your doubts, Madam, cannot shake my faith in this reformation.... And while I remember you, my good, kind mother, (whom God preserve!) never believe that tongue or spirit shall forget this priceless lesson that you have taught them.

In much the same spirit Clemens wrote to Emily Severance two years after the voyage, thanking her for assisting Mary Fairbanks in his Quaker City tutelage: "I shall always remember both of you gratefully for the training you gave me—you in your mild, pervasive way, & she in her efficient tyrannical, overbearing fashion" (27 October 1869). Typically, he closed his 12 December 1867 letter to Mother Fairbanks with a pledge and a plea: "I am improving all the time.... Give me another Sermon."

Clemens spent most of this year-long comic phase on the road. In New York, probably on 27 December 1867, he met Olivia Langdon, whose brother, Charles, had been among his Quaker City shipmates, and passed a few days there with her and her family. While he may have been attracted to her at the time, he hardly seems to have been smitten, and he was not even to see her again until August of 1868, when the comic phase dramatically ended with his profession of love for her. Olivia may have been vaguely on his mind during this interim, but there is no evidence to show

that he was consciously or deliberately "improving" for her sake.[3] Instead, he was hustling up and down the East Coast, returning to San Francisco and the Nevada lecture circuit, giving speeches, writing for newspapers and magazines, trying to complete the manuscript of The Innocents Abroad , and periodically sending off dispatches to Mother Fairbanks regarding her cub's progress. "I am going to settle down some day," he assured her, "even if I have to do it in a cemetery" (17 June 1868).

Clemens's letters during this period are communiqués from an exhilaratingly un settled writer, one whose ethical-esthetic reformation is much less pressing than the day-to-day demands of editors and lecture sponsors. They indicate, however, that he was mindful of his pledge to improve at a time when he was involved in revising the travel letters he had published in the San Francisco Alta California and writing new material for The Innocents Abroad , whose manuscript he virtually completed in June.

An examination of these revisions demonstrates that Clemens consistently pruned indelicacies, slang, and vulgarisms as he transformed his Quaker City correspondence into the text for the book.[4] Given his ambitions at the time, he was apparently as pleased to make these changes as Mother Fairbanks, for one, was to witness them. Improving as he was, Clemens seems also to have been determined to soften his attack on European culture in the course of the Innocents Abroad revisions. A letter to Emeline Beach emphasizes the parallel he saw at the time between the literary and the personal reformations he was trying to accomplish: "I have joked about the old masters a good deal in my [Alta California ] letters," he said, "but nearly all of that will have to come out. I cannot afford to expose my want of cultivation too much. Neither can I afford to remain so uncultivated—& shall not, if I am capable of rising above it" (10 February 1868). While in the West in the early summer of 1868, Clemens submitted a draft of the manuscript to Bret Harte, who, he later claimed, "told me what passages, paragraphs & chapters to leave out." Harte, a more experienced and sophisticated editor than Mary Fairbanks, contributed dramatically to the clipping and polishing not only of The Innocents Abroad but also of Mark Twain. He "trimmed & trained & schooled me patiently," Clemens said, "until he changed me from an awkward utterer of coarse grotesquenesses to a writer of paragraphs & chapters that

have found a certain favor in the eyes of some of the very decentest people in the land."[5] Like a kind of palimpsest, the evolving manuscript itself bore a record of the writer's reformation.

Clemens's attitude toward the revision of both his book and his character reflected the mixture of play and seriousness that typified the comic phase of his reformation. He was able to regard himself, his work, and his persona with a bemused detachment that allowed him to maintain his balance as he anticipated and adjusted to his rising fortunes. The restraints under which he operated, most of them self-imposed, were mild, and his response to them ironic and tolerant. He seems at the time to have been neither threatened nor impaired by his ambition to become conventionally "better" because he himself was aware of its comic dimension and so remained in control of it. This ambition required no violent disjunction between his present and past selves, no repudiation of his earlier life or work for the sake of radical reform. There was no need to cut Samuel Clemens free of Mark Twain; the two could continue to stumble along together. Clemens was candid about his faults and shortcomings, but he was largely self-accepting during the comic phase. "I am not as lazy as I was," he teased Mother Fairbanks, "but I am lazy enough yet, for two people" (12 December 1867). His stance was that of a meliorist and, at that, a meliorist whose attention to reform was easily distracted.

That posture changed drastically in late August 1868, when Clemens paid a long-postponed visit to Elmira and fell thoroughly in love with Olivia Langdon. By the time he departed from the Langdon household in early September he left behind a letter to his would-be sweetheart that reflected the changes in tone and attitude he had begun to undergo. "It is better to have loved & lost you," he wrote Olivia, who had of course turned aside his first advances, "than that my life should have remained forever the blank it was before. For once, at least, in the idle years that have drifted over me, I have seen the world all beautiful, & known what it was to hope. For once I have known what it was to feel my sluggish pulses stir with a living ambition" (7 September 1868). We look in vain for the wink or "snapper" that typically accompanies such a piece of florid writing from Mark Twain. But no wink is forthcoming; the letter continues in the same earnest, superheated fashion and then concludes with a revealing instance of revision: "Write me

something ," Clemens pleads. "If it be a suggestion, I will entertain it; if it be an injunction, I will honor it; if it be a command I will obey it or break my royal neck exhaust my energies trying." The flippant "break my royal neck" has no place here and is virtually obliterated in the manuscript of the letter by a close-looped cross-out.[6] The phrase is appropriate to Mark Twain, of course, as well as to the cub Sam Clemens, but it is clearly inappropriate in the discourse of a man who hopes to establish himself as a suitor worthy of Olivia Langdon. The gap had dramatically widened between what the writer of this letter had been and what he wished to become.

Clemens wanted to be taken seriously by Olivia and her parents—that is, to be taken as a serious man —and in the process he seems to have come to believe that he ought to take himself seriously as well. Thus began a phase of his reformation that might be termed melodramatic, a phase during which he sought more fervently than ever before to embrace conventional values and to prove himself according to conventional standards. It would be reductive and unfair to hold Olivia, the Langdons, or the East accountable for these accommodations on Clemens's part; his preconceived notions of respectability had more to do than they with the transformation of the ironist to the zealot.[7] His courtship of Olivia, however, lent urgency to his reformist intentions and encouraged him to believe that his change for the better could and should be radical rather than ameliorative. He seems, in fact, to have caught himself in a snare he set for her. The more emphatically he pledged himself to improve, the more feverishly he came to believe in the necessity and desirability of a sweeping reformation.

In his early letters he petitioned Olivia—as he had Mary Fairbanks, whose name he freely invoked by way of precedent—to help him mend his heedless ways by assuming the "sisterly" role of ministering angel. "Give me a little room in that great heart of yours," he wrote, "& if I fail to deserve it may I remain forever the homeless vagabond I am! If you & mother Fairbanks will only scold me & upbraid me now & then, I shall fight my way through the world, never fear" (7 September 1868). In a letter of 18 October 1868, he again linked Olivia to Mother Fairbanks, maintaining that "between you you have made me turn some of my thoughts into

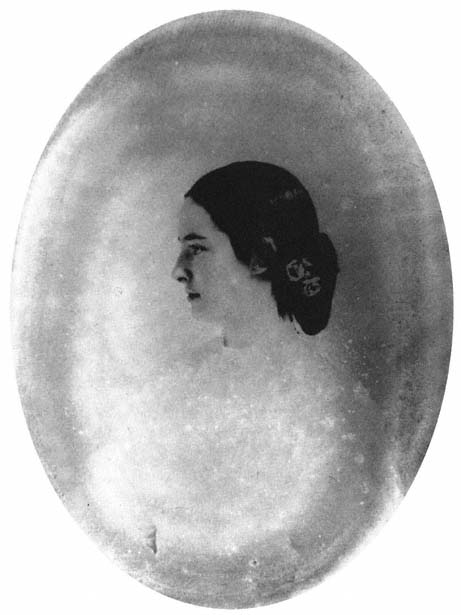

Olivia Langdon, c. 1869. (Courtesy Mark Twain Memorial, Hartford, Conn.)

worthier channels than they were wont to pursue, & benefits like that, the worst of us cannot forget." While Olivia was no doubt susceptible to these appeals, it was Clemens himself who ultimately took their message most to heart.[8] What was needed, he came to believe, was a thorough overhaul of his character and at least a tacit repudiation of his earlier, unregenerate self.

That conclusion, however resolute, was not reached without a good deal of wrenching and ambivalence on his part. During the fall of 1868, while trying to convince Olivia, the Langdons, and himself that he would be settled, serious, and responsible, he seems instinctively to have sought release from the very respectability he was rushing to embrace. While visiting the Fairbankses' Cleveland home during the fall lecture tour, he wrote a piece entitled "A Mystery," which appeared in Abel Fairbanks's Cleveland Herald on 16 November.[9] In "A Mystery" Mark Twain complains that "one of those enigmas which we call a Double" has been marauding around the country, using his name "to borrow money, get rum for nothing, and procure credit at hotels." The double abuses whatever privileges it can wring from the unwary, gives but a single lecture ("in Satan's Delight, Idaho"), and then lapses into full-scale dissipation: "It advertised Itself to lecture and didn't; It got supernaturally drunk at other people's expense; It continued Its relentless war upon helpless and unoffending boarding-houses, and," complains the long-suffering writer, "It was leaving Its bills unsettled, and thereby ruining Its own good name and mine too." The double is last seen riding a stolen horse north from Cleveland, itself a mysterious undertaking.

Clemens has fun on several levels in "A Mystery" and may be revealing a mix of personal feelings as well. Most obviously there is the fun of Mark Twain's trying to pass himself off as a teetotaling pillar of virtue, protesting that his reputation will be devastated by the outrages of the double: "It gets intoxicated—I do not. It steals horses—I do not. It imposes on theatre managers—I never do. It lies—I never do. It swindles landtords—I never get a chance." The reader chuckles along even before he gets to the snapper about swindling landlords because of what he knows of Mark Twain's self-confessed and well-established history as a drinker and liar of western proportions. So the snapper serves more importantly to direct the reader's attention back through the long paragraph which

it concludes, a paragraph of Mark Twain's deadpan assertions about the unsuitability of this particular double:

Now to my mind there is something exceedingly strange about this Double of mine. No double was ever like it before, that I have heard of. Doubles usually have the same instincts, and act the same way as their originals—but this one don't. This one has struck out on an entirely new plan. It does according to its own notions entirely, without stopping to consider whether they are likely to be consistent with mine or not. It is an independent Double. It is a careless, free-and-easy Double. It is a Double which don't care whether school keeps or not, if I may use such an expression. If it would only do as I do. But it don't, and there is the mystery of it.

Superficially the paragraph extends (and even belabors) Mark Twain's lament that the double misrepresents him, the joke again arising from the reader's recognition that the traits the writer regards as "new" and "inconsistent" in the double are among those which (the reader has long since come to believe) typify the original. That is, he knows him to be "independent ..., careless, free-and-easy," just as he knows him to be a tippler and a truth stretcher. The language of the paragraph reinforces the joke by reminding the reader of Mark Twain's rough edges even as he proclaims his respectability.

But on another level the contrast between double and original, between carelessness and responsibility, could not have been entirely a laughing matter for Clemens in November of 1868. His courtship of Olivia, which reinforced and in part depended upon his determination to reform, was driving him more and more sincerely to espouse the very respectability that Mark Twain fraudulently assumes in "A Mystery." Ten days after the piece appeared in the Cleveland Herald , he and Olivia became provisionally engaged, a circumstance which bears witness to his own and the Langdons' faith in his potential to develop settled and responsible habits. However eager he may have been to enter into such a commitment, "A Mystery" imaginatively suggests his ambivalences about the prospect, ambivalances that he was very likely unable to express in any other way. The double, most notably, is "careless" not only of Mark Twain's supposed good example, but also of social proprieties generally. He is "independent" and "free-and-

easy" in ways that respectable people are not. Through this early and rather rudimentary use of the other self, which was to figure so importantly in his work, Clemens betrayed confusion about the relationship between respectability and unregeneracy in his own makeup. Because the humor of the piece depends upon the implication that, despite his complaints, Mark Twain shares many of the double's lamentable habits, "A Mystery" serves ultimately to reaffirm his bad-boy reputation. Moreover, it does so virtually on the eve of Clemens's engagement, at a time when he was consciously doing all he could to put such a reputation behind him. Unless Mark Twain, too, were to undergo a reformation, it seems that the distinction between him and his creator, a distinction which had become increasingly blurred since Clemens introduced the pseudonym in 1863, would inevitably sharpen and the distance between them dramatically widen.

This process of dissociation may have been at the back of Clemens's mind as he wrote "A Mystery." The piece closes with Mark Twain's discovery that his double is no double after all, but "only a very ordinary flesh and blood young man, given to idleness, dissipation and villainy, and entirely unknown to me or any of my friends." One can almost hear erstwhile suitor Clemens, at this moment wishing that his own character were so genuinely undivided, enthusiastically disowning his earlier, unregenerate self and hoping that "his friends" the Langdons would be willing to overlook the resemblances between the two. The disfranchised doppelgänger, who in his penchant for idleness, dissipation, and villainy bears a likeness to the other, or disreputable, Clemens/Twain, is roundly denounced as "a rascal by nature, instinct, and education, and a very poor sort of rascal at that." But at the last moment, his righteous indignation spent, the writer admits a grudging sympathy for the impostor: "I ought to hate him, and yet the fact that he has been able to borrow money and get board on credit by representing himself to be me, is so comfortably flattering that I own to a sort of sneaking fondness for the outcast for demonstrating that such a thing was possible." The joke, serviceable in its own right, allows Mark Twain to soften his denunciation of the heedless young charlatan just as "A Mystery" ends, adding a final wrinkle of complexity to a piece already noteworthy for its overlapping layers of conscious and semiconscious irony. As we work through

these layers, we find writer, persona, and double caught in tangles of imperfectly understood feelings, sometimes attracting, sometimes repelling or rejecting, one another. Whatever else it may suggest, "A Mystery" demonstrates that just ten days before his provisional engagement, and probably while he was a guest in Mother Fairbanks's home, Clemens traded upon Mark Twain's reputation as a rough-and-tumble man of the world even as he insinuated a mild protest against the respectability to which he had pledged himself.

That pledge assumed the weight of a holy vow when he and Olivia became conditionally engaged on Thanksgiving 1868. The conditions, he wrote to Mother Fairbanks, had principally to do with his convincing all involved that his reformation was genuine and consequential. "She must have time to prove her heart & make sure that her love is permanent," he said of Olivia. "And I must have time to settle , & create a new & better character, & prove myself in it & I desire these things, too" (26–27 November 1868). Earlier in the letter, in somber and stately language, he spoke of his intentions:

I touch no more spiritous liquors after this day (though I have made no promises)—I shall do no act which you or Livy might be pained to hear of—I shall seek the society of the good—I shall be a Christian . I shall climb—climb—climb—toward this bright sun that is shining in the heaven of my happiness until all that is gross & unworthy is hidden in the mists & the darkness of that lower earth whence you first lifted my aspiring feet.

There is no intentional humor here, none of the irony of "A Mystery," nor any of the teasing that characterized the cub's earlier correspondence with his mother. Clemens writes as the Rake Reformed, his grandiloquence and almost palpable earnestness emphasizing his melodramatic self-regard. In his fiction he had ridiculed and would continue to ridicule the self-proclaimed bornagain sinner, but for a while, at least, in the fall of 1868, he seems with all sincerity to have wanted to play the part. His anxiety to improve, first substantially stirred by his own ambition and the proddings of Mary Fairbanks, threatened now to alienate him from his past and in so doing to open a chasm between writer and persona that not even Clemens's invention could bridge.

Olivia's mother, Olivia Lewis Langdon. (Courtesy Mark Twain Papers,

The Bancroft Library)

No doubt with the best intentions, the Langdons initially promoted the widening of this chasm by accepting with gratitude the notion that their would-be son-in-law had undergone a radical transformation. On 1 December 1868 Olivia's mother wrote Mary Fairbanks, "I have learned from ... your conversation, or writing or both,—that a great change had taken place in Mr Clemens, that he seemed to have entered upon a new manner of life, with higher & better purposes actuating his conduct."[10] When Clemens learned that Fairbanks had responded to Mrs. Langdon with what he called a "cordial, whole-hearted endorsement," he gratefully declared, "When I prove unworthy of the service you have done me in this matter, & the generous trust you have placed in me, even in the slightest degree, I shall be glad to know that that day is the last appointed me to live" (24–25 December 1868). Reform had become a serious matter, and the past a source of embarrassment and chagrin. But Clemens was determined that his better self would prevail. "Though conditions & obstructions were piled as high as Chimborazo," he wrote Olivia, "I would climb over them all!" (4 December 1868). By way of promoting a good example of tolerance for her family to follow, Clemens ingenuously quoted his new Hartford friend, Reverend Joseph Twichell, who had written him, "I don't know anything about your past.... I don't care very much about your past, but I do care very much about your future" (4 December 1868). Over the next two months Clemens wrote frequently in this vein as his probation continued, even going so far as to admit to Jervis Langdon, "I think that much of my conduct on the Pacific Coast was not of a character to recommend me to the respectful regard of a high eastern civilization" (29 December 1868). He argued, however, that he was a changed man and that Olivia was both the occasion and the instrument of his redemption. On 19 January 1869 he wrote her—appropriately, from the Fairbankses' Cleveland home—"You will break up all my irregularities when we are married, & civilize me, & make me a model husband & an ornament to society—won't you, you dear matchless little woman?" Five days later he summarized his case to her: "I have been, in times past, that which would be hateful in your eyes.... I say that what I have been I am not now; that I am striving & shall still strive to reach the highest altitude of worth, the highest Christian excellence." The best testimony of the Langdons'

faith in this renunciation of a misspent youth is their approval of the couple's formal engagement on 4 February 1869. In order to gain that faith, and for the sake of a newly defined self-esteem, Clemens believed that he had to ransom his past to his future. What was he now to do with Mark Twain?

His circumstances at the time dictated at least a partial answer to the question. During the fall and winter of 1868–69, Clemens was under obligation to two contracts which would further Mark Twain's national reputation and keep him in the public eye through the following year. The first was his commitment to his publisher, Elisha Bliss, to see The Innocents Abroad through the final stages of editing and revision, a process which lasted well into the summer of 1869. The second was his agreement to lecture during the 1868–69 season. One effect of these obligations was to make it impossible for Clemens entirely to set his persona aside during his courtship of Olivia, even had he wanted to. In fact, almost all the letters which make up the early, idealizing phase of their relationship, when his intention to reform was most fervid, were written while he was on the lecture circuit, taking Mark Twain and "The American Vandal Abroad" before the public several nights a week.

This has the look of a remarkably lucky coincidence, one of those biographical circumstances that force apparently irreconcilable aspects of a personality into an accommodation. Had such a circumstance not prevailed at the time, it is much more likely that the chasm between Samuel Clemens and Mark Twain would have widened, perhaps irreparably, the latter becoming merely a caricature or mascot of the former. This had, after all, been the fate of most other western humorists, "phunny phellows" who had allowed tricks of dialect and spelling to become their stocks-intrade. That Clemens may have wanted to repudiate Mark Twain as an avatar of his earlier, unregenerate self is suggested from time to time in his love letters, especially when he stresses the distinction between person and persona. On 4 December 1868, for example, he wrote Olivia, "Your father & mother wanted to see whether I was going to prove that I have a private (& improving) character as well as a public one." By the end of the month he was vilifying his earlier work and, by implication, the earlier self responsible for it: "Don't read a word of that Jumping Frog book, Livy—don't . I hate to hear that infamous volume mentioned. I would be glad to

know that every copy of it was burned, & gone forever. I'll never write another like it" (31 December 1868). But the fact of the matter is that between 17 November 1868 and 3 March 1869 Mark Twain was obligated to give more than forty lectures in cities in the Northeast and Midwest and that Clemens had no choice but to come to terms with his persona while he was most deeply in the throes of reformation, writing Olivia almost nightly of his progress.

The result was an accommodation on both sides. Mark Twain saved Sam Clemens from himself, and the lover saw to it that the lecturer revealed a fuller measure than before of his humanity. If the first of these claims has the ring of overstatement about it, it bears the ring of truth as well. The grueling winter lecture season provided an antidote for Clemens's melodramatic self-absorption by keeping him constantly in touch with qualities in his personality upon which Mark Twain thrived—detachment, irony, self-deprecation, testiness, and of course humor. Such an environment tempered the reformer's zeal and helped him recognize the complex interdependence of both halves of the Clemens/Twain identity. At times he bemoaned the consequences of this interconnection, as when he complained to Mrs. Langdon, "I am in some sense a public man, ... but my private character is hacked, & dissected, & mixed up with my public one, & both suffer the more in consequence" (13 February 1869). However, this intermingling of private and public character seems to have served Clemens well during his probationary period, for if the lecturer helped the lover keep his feet on the ground, the lover was particularly determined that the lecturer come across as more than a bumpkin or a buffoon.

Clemens was concerned about his ability to satisfy the demands of eastern audiences even before he fell in love with Olivia and became all the more mindful of what he considered eastern proprieties. On 5 July 1868 he reported to Mary Fairbanks his satisfaction with a San Francisco lecture he had just given but added, "I do not forget that I am right among personal friends, here, & that a lecture which they would pronounce very fine, would be entirely likely to prove a shameful failure before an unbiased audience such as I would find in an eastern city." By the time he began the winter lecture tour on 17 November 1869—in Cleveland, under Mother Fairbanks's watchful eye—he felt considerable pressure, much of it

self-imposed, to demonstrate that Mark Twain was more than a "mere" humorist. So it must have been especially gratifying to him when, in her Herald review of the performance the next day, Mother Fairbanks proclaimed her approval: "We congratulate Mr. Twain," she wrote, "upon having ... conclusively proved that a man may be a humorist without being a clown. He has elevated the profession by his graceful delivery and by recognizing in his audience something higher than merely a desire to laugh."[11] Such a notice, especially at the outset of the tour, could only have helped reassure him that it was unnecessary to cut himself off from his persona in order to secure the regard of the respectable and fashionable people among whom he hoped to further his reputation. He must also have realized that praise of this sort would strike a resonant chord in Olivia. "Poor girl," he later wrote Mary Fairbanks, "anybody who could convince her that I was not a humorist would secure her eternal gratitude! She thinks a humorist is something perfectly awful" (6 January 1869).

The lecture performances of 1868–69 partially solved the problems that Clemens faced at the time in presenting Mark Twain to "proper" eastern audiences without eviscerating him. They were instrumental in allowing him to enlarge and redefine the humorist's prerogatives. Those who attended these performances saw the lecturer shamble across the stage, assume a careless attitude at the lectern, and begin drawling out an anecdote, apparently in the most laconic and indifferent way. Perhaps their worst suspicions about Mark Twain were confirmed: here was an irreverent idler with little to recommend him but his cheek. As he talked, however, a strange upheaval took place, first in isolated spots in the hall, then in waves, then in sweeping explosions of laughter, surprise, and recognition. The uninitiated realized that they had been taken in. The indolence and indifference were part of a pose. Mark Twain proved to be a very funny man, but not simply funny in a broad or oafish way. His humor depended upon drollery, flashes of wit, and bright ironies that challenged an audience and kept it awake. The lecture platform allowed Clemens to show that Mark Twain's unrefinement was superficial, that it juxtaposed and so rendered only more powerful the operation of a complex and penetrating intelligence. At a time when being taken seriously was of crucial importance to Clemens, the 1868–69 lectures provided him the op-

portunity to experiment with the vital tension between humor and seriousness that was to characterize his best work. "Mere" humorists were content simply to make the public laugh; especially when the impulse to reform was strong upon him, he was determined to make it think and feel as well.

However sincere this determination, manifestations of reform in Mark Twain were much more modest, subtle, and ameliorative than those which Clemens himself undertook; Mark Twain remained the conservative partner in the complex equation of identity, while Clemens was, for a time at least, the radical. Both person and persona underwent change that carried them in the direction of increasing moral responsibility, respectability, and even piety, but the persona stayed relatively stable while the person swung through dramatic arcs of regret, resolution, and reformation. Mark Twain's relative stability must have been a source of both comfort and consternation for Clemens as he strove to redefine his own "proper" identity during the year that followed his declarations of love to Olivia in September of 1868. There was a kind of solidity and consistency about Mark Twain—qualities which were reinforced by his audience's expectations—that contrasted sharply with the radical mutability which Clemens and others wished to attribute to his own character at the time. Mark Twain had to remain essentially Mark Twain, notwithstanding the broadening and deepening he was undergoing, but Clemens believed that he himself was to become something quite different from what he had been. Never before had there been such cause for isolating person from persona; never again would the two stand so clearly apart from one another.

It is not surprising, given this tension, that Clemens wrote comparatively little during this year of courtship and contrition. In a letter to his family of 4 June 1869 he acknowledged this drought and offered a partial explanation: "In twelve months (or rather I believe it is fourteen) I have earned just eighty dollars by my pen—two little magazine squibs & one newspaper letter—altogether the idlest, laziest, 14 months I ever spent in my life.... I feel ashamed of my idleness, & yet I have had really no inclination to [do] anything but court Livy. I haven't any other inclination yet ." Although there is some exaggeration of his inactivity here, perhaps because Clemens was late in sending money home to his mother, it is true

that his productivity as a writer fell off sharply between September 1868 and the following August, when he became an editor of the Buffalo Express . And while other circumstances undoubtedly contributed to this falling off—among them the winter lecture tour and the burden of reading proof for The Innocents Abroad in the spring—the primary cause of Clemens's unproductivity during this year of reform was very likely his alienation from the imaginative resources embodied in Mark Twain. Person and persona had to be reconciled before these resources could again be successfully tapped.

That reconciliation came gradually as Clemens grew confident of Olivia's love and the fever of his passion to reform inevitably cooled. Eventually a new personal equilibrium evolved which integrated the Clemens/Twain identity once again and comfortably blurred distinctions between man and writer. Evidence of this evolution emerges intermittently from Clemens's correspondence and from his rare newspaper and magazine pieces of early 1869, among them an article entitled "Personal Habits of the Siamese Twins," which was written on 14 May and appeared in the August issue of Packard's Monthly . Significantly, Clemens treats the famous twins Chang and Eng as two distinct personalities vying for control of a single body. Like "A Mystery," "Personal Habits" is a product of the reformation year with obvious and inviting psychological overtones. Writing about the sketch to Olivia on 14 May, Clemens said, "I put a lot of obscure jokes in it on purpose to tangle my little sweetheart," a teasing reference to her literalmindedness in trying to fathom plays of wit or words. But the more provocative tangle in "Personal Habits" is that involving the identities of Chang and Eng, a tangle which Clemens may have seen as a grotesque and literal embodiment of a "double nature" not unlike his own. "As men," he says in the piece, "the Twins have not always lived in perfect accord; but, still, there has always been a bond between them which made them unwilling to go away from each other and dwell apart."[12] By May of 1869 Clemens may well have felt a similar unwillingness, or recognized a similar inability, in the matter of divorcing himself from his past and from those elements of his character which were most recognizable in Mark Twain.

"Personal Habits" obliquely implies such a recognition while it explores the tension between sharply conflicting impulses trapped

within a single identity. Together with "A Mystery," it demonstrates that Clemens's lifelong fascination with doubleness, twinning, and paired consciousnesses first came into focus as the disintegrative fervor of self-reformation gradually gave way to the reconciliation of apparent polarities in his personality.

Even by the beginning of 1869, some of Clemens's zeal to reform was exhausted, and his more characteristic realism had begun to reassert itself. Melodramatic self-recrimination gave way to intervals of candor and whimsy and to more pointed reckonings of his chances to get ahead in Cleveland or Hartford or Buffalo. Evidence of this realistic or restorative phase of his reformation appears in a comparatively early courtship letter, where, in language reminiscent of his correspondence with Mary Fairbanks just a year earlier, he acknowledges his fiancée's imperfections and his own incipient worthiness. "I am grateful to God that you are not perfect," he told Olivia. "God forbid that you should be an angel. I am not fit to mate with an angel—I could not make myself fit. But I can reach your altitude, in time, & I will " (5–7 December 1868). As his confidence in her feelings matured, his declarations of intention grew less shrill. On 20 January 1869 he wrote, "I know that you are satisfied that whatever honest endeavor can do to make my character what it ought to be, I will faithfully do." On 6 March, just a month after they had become formally engaged, he summed up his position: "I know that I am not your ideal of what a husband should be, ... & so your occasional doubts & misgivings are just & natural—but I shall be what you would have me, yet, Livy—never fear. I am improving. I shall do all I possibly can to be worthy of you." Clemens is still the reformer in these representations, but no longer the desperate, sentimental acolyte come to worship at the shrine. Self-condemnation has begun to give way to self-understanding and self-acceptance; the petitioner is still penitent, but no longer abject. By May he could write Olivia, "I think we know each other well enough ... to bear with weaknesses & foolishnesses, & even wickednesses (of mine)" (19–20 May 1869).

With the formal announcement of his engagement to Olivia Langdon on 4 February 1869, Clemens arrived at a psychological watershed. The ordeal of attainment was substantially behind him; the security of his hard-won position allowed him in exultant moments to relax and enjoy his prospects. "I don't sigh, & groan &

howl so much, now, as I used to," he wrote the Twichells; "No, I feel serene, & arrogant, & stuck up—& I feel such pity for the world & every body in it but just us two" (14 February 1869). These spells of complacency were fleeting, and intermixed with them were periods of doubt and chagrin, but case was gradully displacing urgency in Clemens's correspondence, and playfulness now vied with piety in his appeals to Olivia. "To tell the truth," he told her, "I love you so well that I am capable of misbehaving, just for pleasure of hearing you scold" (12 January 1869). Through the spring and summer of 1869 Clemens wondered at his good fortune and learned to trust it. On 4 June he confessed to Mother Fairbanks, "I had a dreadful time making this conquest, but that is all over, you know, & now I have to set up nights trying to think what I'll do next."

By June of 1869 "what I'll do next" came to be a professional as well as a personal question for Clemens. He was in the last stages of proofreading The Innocents Abroad , was obligated to prepare a lecture for the coming season, and had been relatively inactive as a writer of anything but love letters since his declarations to Olivia nearly a year earlier. But the restoration of his equilibrium was readying him to return to work. As Olivia and her family came to accept him, and as he concomitantly came to understand that a radical reformation of his character was unlooked for and unnecessary, he regained access to the sources of his vitality as a writer— his past, his skepticism, even his irreverence. The Langdons themselves stimulated and helped sustain this restoration by remarkably and, it would seem, wholeheartedly accepting their would-be son-in-law in the few months that passed before the engagement was formally announced. Clemens was as proud of this trust as he was grateful for it. In a letter to his sister he described the Langdons' devotion to Olivia and then added, "They think about as much of me as they do of her" (23 June 1869).[13] To their credit, Olivia and her family seem often to have been fairer and more perceptive in appraising her suitor's character than he was himself. While they were no doubt impressed by the sincerity of his pledges to reform, they were also quick to appreciate those qualities in him which required no reformation—honesty, generosity, industry, devotion, good-heartedness—and to give him their confidence. It was of this confiding acceptance that Olivia wrote to her fiancé later in the

year: "I am so happy, so perfectly at rest in you, so proud of the true nobility of your nature—it makes the whole world look so bright to me."[14] Clemens had proved "worthy," after all, and he may have come to understand that in many respects he had been worthy all along.

These acts of trust and reinforcement shortened the psychological distance Clemens had to travel before returning to the equilibrium that allowed him once again to function as a professional writer. By the time he deliberately resumed that function in late August 1869, by becoming an editor of the Buffalo Express , the strenuous and distortive melodramatic phase of his reformation had subsided, and he was in a position to consolidate the gains and losses it had brought: Mark Twain and Samuel Clemens met just about where they had parted, although both had become more consciously serious and a bit more responsive to the conventions of the eastern middle class. The Clemens/Twain identity was returning to the careless integration which rendered its halves only imperfectly differentiable. And, most important, the bridge between Clemens's past and his future could remain intact, bearing the rich cargo of recollection and reminiscence that was to sustain his major work.