Tragicomedies

As Corinth's three closest friends embarked on their individual pictorial explorations, Corinth himself experienced a minor crisis that made him unusually receptive to their experiments. Still dissatisfied with his handling of anatomy in Diogenes and the Pietà , he felt he needed further practice in drawing from the live model. Eckmann, whom Corinth fondly remembered as his "spiritus rector," who supported and steadied him whenever he was in danger of losing his footing,[57] suggested that he try making some prints; Corinth began a series of studies that eventually resulted in his first graphic cycle, Tragicomedies , nine etchings completed in 1893 and 1894. Working "daily, for months on end, . . . with individual figures and groups of several models," he was so taken with this project that he, too, was tempted to give up painting for good.[58] Corinth had in mind for the cycle motifs of "eccentric originality," as he put it, with which he hoped to astonish and impress his colleagues.[59] His professed intention explains both the odd emblematic details in some of the compositions and the farcical tone that turns each episode into a true tragicomedy, no matter how serious the subject. The cycle has no thematic unity. Instead, the illustrations follow in random succession.

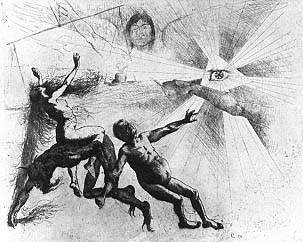

The first etching in the series, Walpurgis Night (Fig. 42), is based on Goethe's description of the witches' nocturnal ride to the Brocken, their annual meeting place in the Harz Mountains. Faintly visible in the background, old Dame Baubo on her sow and several other shadowy figures on brooms hurry through the sky as four youthful witches, accompanied by a flock of ravens, encircle a skull suspended in midair. A shooting star streaks through the sky at the upper right. Surviving drawings for the cycle indicate that Corinth prepared the etchings with considerable care. He began with quick preliminary sketches and then drew the individual figures from the model, subsequently incorporating these studies into a more finished composition drawing for transfer to the copper plate. In Walpurgis Night the postures of the floating witches can still be recognized as positions assumed by the models in the studio, standing, sitting, or lying down. There is special emphasis on the contours, and strong contrasts of light and shade render the major figures fully tangible. The composition itself, however, is simplified and derives its effect from the silhouette formed by the interlocking figures. This stylistic ambivalence recalls Stuck's Guardian of Paradise , and in the second etching of the cycle, Paradise Lost (Fig. 43), the angel's arm from Stuck's painting reappears with only minor modifications. As in the preceding print, the fully modeled figures form a striking pattern against the white paper ground.

Figure 42

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies: Walpurgis Night , 1893.

Etching, 34.2 × 41.7 cm, Schw. 5 II.

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna (1910/406/5).

Figure 43

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies: Paradise Lost , 1893.

Etching, 35.0 × 41.8 cm, Schw. 5 III.

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna (1910/406/4).

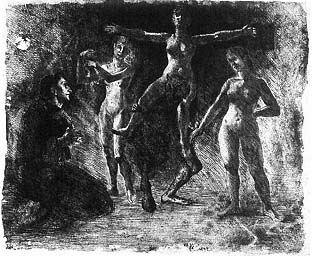

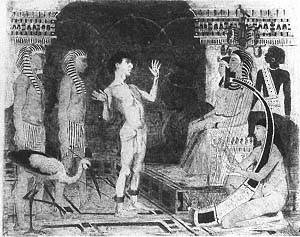

Figure 44

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies: The Temptation of

Saint Anthony , 1894. Etching, 34.3 × 42.2 cm., Schw. 5 IV.

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna (1910/406/8).

Figure 45

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies: The Women of

Weinsberg , 1894. Etching, 35.0 × 42.5 cm, Schw. 5 VII.

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna (1910/406/6).

Here, however, the stylistic ambiguity of the composition is intensified by the emblematic imagery: a large eye in the center of a triangle, symbolizing the Holy Trinity, radiates beams of light; the powerful arm of an otherwise unseen angel brandishes a flaming sword; and the figure of Saint Michael holds aloft the scales that weigh the moral frailty of the human heart.

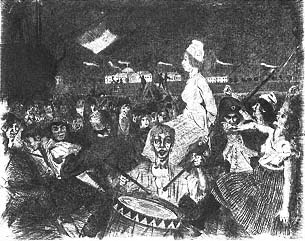

Three of the five remaining narrative episodes of the cycle have greater stylistic unity. In each of these the naturalistic portrayal of the figures is matched by an appropriately atmospheric setting. The Temptation of Saint Anthony (Fig. 44) was clearly inspired by Félicien Rops's woodcut of the same subject. The elongated faces and caps of the men in The Women of Weinsberg (Fig. 45) recall similar features in paintings by Dirk Bouts. This print depicts the amusing story told about the siege of the Bavarian town of Weinsberg in 1140, when the Hohenstaufen enemy Conrad III accepted the surrender of the town on the understanding that only the women would be spared; they were allowed to leave the town with whatever they could carry. The resourceful women met the conditions of the agreement by marching forth with their husbands on their backs. In the more familiar subject Marie Antoinette on Her Way to the Guillotine (Fig. 46) the unfortunate queen sits stiffly upright in a cart surrounded by a jeering mob. This print would seem to presuppose knowledge of the famous sketch, now in the Louvre, in which Jacques Louis David recorded Marie Antoinette's last journey.

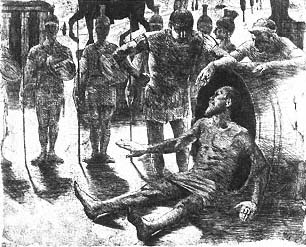

The tension between naturalistic modeling and flat decorative elements is again evident in Joseph Interprets the Pharaoh's Dreams (Fig. 47) and Alexander and Diogenes (Fig. 48). Amid the splendor of the king's palace Joseph strikes a lively pose as he interprets the dreams of the seven lean years of corn following the seven abundant years. The idea of illustrating the dreams in the diaphanous roundels visible in the archway may have been inspired by Peter von Cornelius's painting of the same subject in the fresco cycle for the Casa Bartholdy in Rome, transferred to the National Gallery in Berlin around 1886. The story of Alexander's encounter with Diogenes is told by Plutarch and Diogenes Laërtius, both of whom describe how Alexander once invited the philosopher to ask any favor. Diogenes, who despised all worldly possessions to the extent of making his home in a tub, requested that Alexander step aside, since the king was shading him from the sun. The rigid figures of Alexander's soldiers form an ornamental screen behind the two men—an amusing contrast with their own relaxed postures. Analogous contrasts in the other prints produce the same effect. For example, against the noble emblem of the all-seeing eye of God the fat figures being carried off by Lucifer appear doubly grotesque; the repose of Pharaoh and his queen intensifies the lively gestures

Figure 46

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies: Marie Antoinette on Her

Way to the Guillotine , 1894. Etching, 35.0 × 42.3 cm, Schw.

5 VIII. Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna (1910/406/7).

Figure 47

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies: Joseph Interprets the

Pharaoh's Dreams , 1894. Etching, 34.4 × 42.3 cm, Schw.

5 V. Landesmuseum Mainz, Graphische Sammlung.

Figure 48

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies: Alexander and Diogenes ,

1894. Etching, 34.8 × 42.3 cm, Schw. 5 VI.

Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich.

of the jabbering Joseph; and there is no doubt that the hefty women of Weinsberg are fully up to the task of rescuing their skinny husbands, while Marie Antoinette seeks to preserve an air of dignity amid the throng.

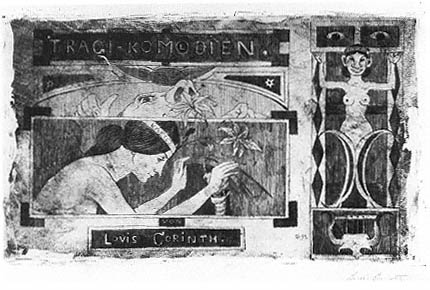

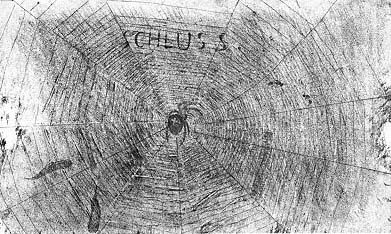

The title page of the cycle (Fig. 49) is the most stylized of the nine etchings and sets the tone for the mocking conception that underlies the individual episodes. Within a frame of predominantly geometric design, Clio, the muse of history, lifts a curtain to reveal a human skeleton. In the surmounting arch an enormous face appears, seen from below in strong foreshortening, its large nose sniffing greedily at a blossom that rises from the panel below. The arbitrary choice of the themes is summed up in the closing vignette (Fig. 50). Here a spider in the center of a web contentedly surveys its catch: the flies trapped in the threads.

Two rapidly sketched pencil drawings now in East Berlin, The Rape of the Sabine Women and The Prodigal Son , belong to the themes from which Corinth assembled Tragicomedies , although the episodes themselves were not included in the cycle. They illustrate the kind of first ideas that preceded the etchings. Of the two, The Prodigal Son (Fig. 51) shows especially well that a humorous conception guided Corinth from the beginning, for here his last painting from Königsberg (see Fig. 35) has been turned into a ludicrous persiflage.

Figure 49

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies : Title Page, 1894. Etching, 21.0 × 34.5 cm,

Schw. 5 I. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich.

It has been suggested that the etchings of Tragicomedies were influenced by Max Klinger's treatise Malerei und Zeichnung (Leipzig, 1891),[60] in which the expressive properties of painting are distinguished from those of the graphic arts. The eccentric character of the cycle indeed suggests that Corinth was familiar with Klinger's idea that whereas painting is bound to the material aspects of things, drawing offers the freedom of poetic license.[61] It is logical to assume that as Corinth learned the technique of etching, he familiarized himself with the thinking of a recognized master in the field. Moreover, since meeting Klinger in Berlin in the winter of 1887–88 he most likely followed his work with interest and knew some of the views Klinger expressed privately, such as the notion that by "placing a carefully modeled object against an undefinable or neutral background," the graphic medium could "depict elements of fantasy that painting can command only under certain conditions."[62] Both Walpurgis Night and Paradise Lost reflect that approach. But even though the cycle conforms to Klinger's contention that "all graphic artists develop in their work a notable tendency toward irony, satire, and caricature,"[63] Corinth clearly did not share Klinger's underlying ethical disposition. Klinger believed that graphic artists "prefer to accentuate weaknesses. . . . from their work rises nearly always one fundamental chord: the world should not be like

Figure 50

Lovis Corinth, Tragicomedies : End Page, 1894. Etching, 21.0 × 34.9 cm,

Schw. 5 IX. Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna (1910/406/9).

Figure 51

Lovis Corinth, The Prodigal Son , 1894. Pencil, 25.6 × 34.4 cm.

Staatliche Museen, Berlin (DDR) (11/6291).

this!"[64] As Corinth himself admitted, Tragicomedies was not meant to be critical but "eccentric," and—as the concluding vignette of the cycle illustrates unequivocally—he never pretended to have selected his motifs out of a deeply felt ethical commitment.

In the final analysis, Tragicomedies marks an important stage in Corinth's development, for in this cycle he first found the irreverent tone that was to set his mature figure compositions apart from his plodding student work. And he soon learned that the "eccentric originality" with which he had intended to astonish and impress his fellow artists in Munich could also gain him the attention of the public at large. When Corinth exhibited the etchings at Eduard Schulte's gallery in Berlin in the winter of 1894–95, one critic went so far as to rank him with Max Klinger as a printmaker. Calling Corinth a "visionary realist," the same critic praised the cycle for its "raw and instinctual naïveté."[65]