Two

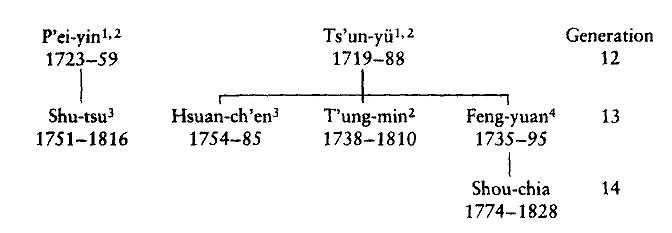

The Chuang and Liu Lineages in Ch'ang-chou

Chuang Ts'un-yü's founding of the New Text school in Ch'ang-chou in the eighteenth century and the predominance of his grandson Liu Feng-lu as his chief nineteenth-century disciple suggest that the Ch'ang-chou school depended on the political and economic strength (as well as the cultural resources) of the Chuang and Liu lineages. By turning now to these prominent lineages in the Yangtze Delta, I hope first to show how they navigated the late Ming social, political, and economic changes we have discussed above.

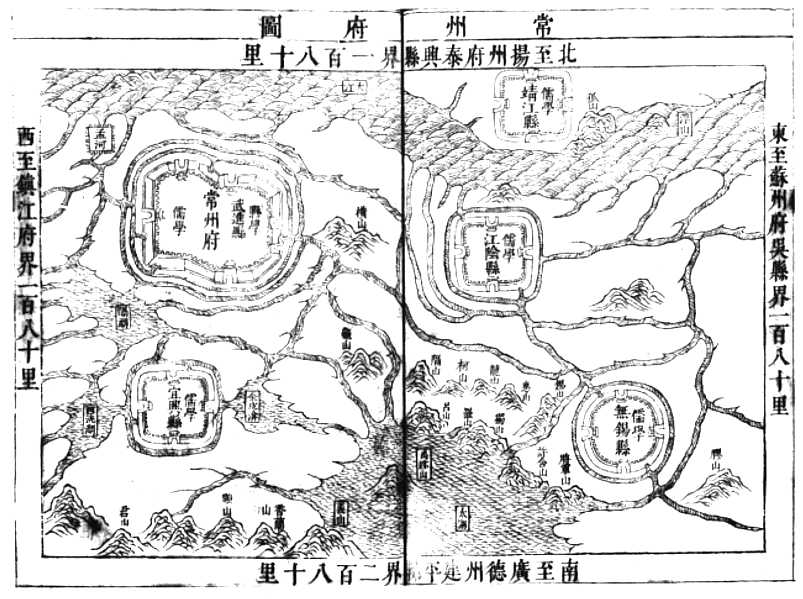

An investigation of Ch'ang-chou elite society during the late Ming will also reveal that after Ch'ing rule brought peace and stability to the Yangtze Delta the local gentry managed not only to survive the Manchu conquest but also to prosper as never before. Our inquiry documents how ideological transformations can be embodied in particular people caught up in specific social and historical contexts. The prominence of the Chuang and Liu lineages in Ch'ang-chou society (map 4) and their ties to the rise of the Ch'ang-chou school in the late eighteenth century enables us to glimpse the social icebergs that lurked beneath intellectual life in late imperial China.

The Beginnings of the Chuangs

The Chuang lineage, particularly the second branch (erh-fen ) to which Chuang Ts'un-yü's family belonged, first came to prominence in Ch'ang-chou in the late fifteenth century. Like many other lineages

south of the Yangtze River, the Chuangs traced their line back to families that migrated from north China during the great social and economic dislocations that preceded the eventual fall of the north to the Jurchen. The Chuangs had already established a beachhead in Chiang-su Province in the eleventh century. They settled in Chen-chiang, on the southern bank of the Yangtze, from where the Grand Canal continued south toward Ch'ang-chou, Su-chou, and Hang-chou.

Robert Hartwell notes that the chief indicator of the profound social changes in China from 750 to 1550 was the major demographic shifts from north to south China. In the six centuries that preceded the establishment of Ming rule in 1368, successive waves of migration had filled in the frontiers of various southern macroregions. These dynamic inter-regional settlements were accompanied by rapid population growth and a "filling up" of the rice-producing areas in the Yangtze Delta.[1]

As participants in these important demographic shifts, some of the Chuangs left Chen-chiang (ca. 1086-92?) and settled in Chin-t'an County, further inland and south of the Yangtze River. Such moves to hinterland counties in search of fortune were a typical migration pattern for segmented branches of core lineages. Chuang I-ssu, in the fifth generation of the Chuangs who resided in Chin-t'an, achieved distinction as prefect of Ch'ang-chou Prefecture from 1102 until 1106. Later he was appointed to the Hanlin Academy. Thereafter, segments of the Chuang lineage continued to scatter throughout the Lower Yangtze.

Initially a lesser segment that had become allied to another family in the hinterlands, the Chuangs in Ch'ang-chou were a lineage to be reckoned with by the late fifteenth century. In the eighth generation of the Chin-t'an descent group, Chuang Hsiu-chiu married into a Ch'ang-chou family, surnamed Chiang, which had no male heir. Accordingly, he took the place of a son (chui ) for this family and moved to Ch'ang-chou. Uxorilocal marriage was a common strategy among important lineages in the Lower Yangtze since at least Sung times. The son of a family with higher social status could establish a new segment of the lineage by moving to another community and marrying the daughter of a family with no heir. But rather than carrying on the family line for the heirless family (the usual procedure in uxorilocai marriages), the son continued to use his own surname in a new community. By moving to Ch'ang-chou, Chuang Hsiu-chiu could take advantage of an entrenched

[1] Hartwell, "Demographic Transformations of China," esp. pp. 391ff.

Map 4

Gazetteer Map of Ch'ang-chou Prefecture and Counties

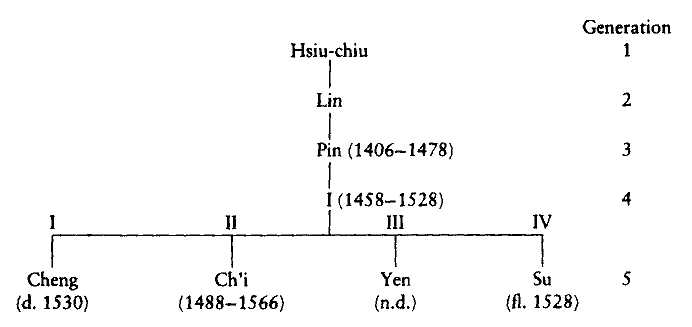

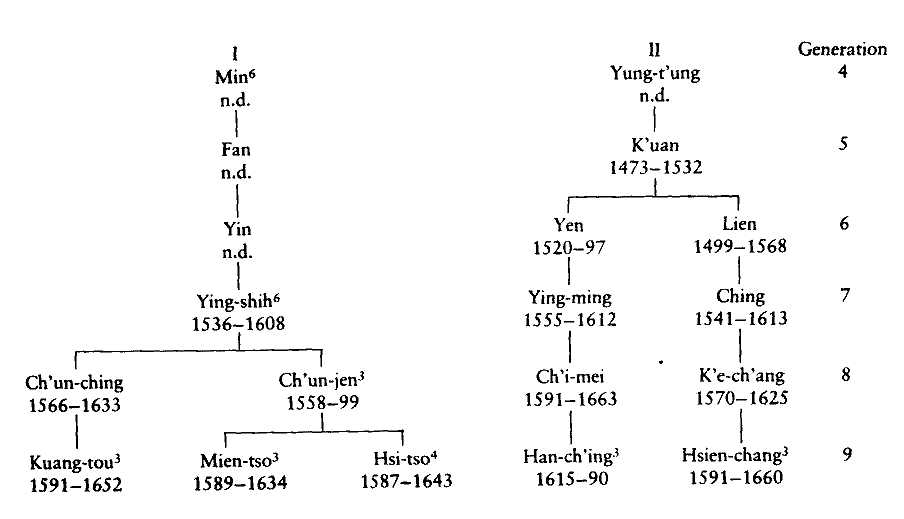

Fig. 4.

Major Segments of the Chuang Lineage in Ch'ang-chou during the Ming Dynasty

family that had become fused with the Chin-t'an Chuangs. Thus, by the fifteenth century another segment of the Chuangs bad come into existence, dating themselves back to Chuang Hsiu-chiu's move to Ch'ang-chou.[2]

The rise of the Ch'ang-chou Chuangs to high social standing began in the fourth generation (in Chuang Hsiu-chiu's line), when Chuang I took the chin-shih degree in 1496. Chuang I's academic success, and the high political office that such success brings, provided the financial resources from which four major branches in the Ch'ang-chou lineage developed (fig. 4). The second branch of the Ch'ang-chou Chuangs, who descended from Cbuang I, rose to particular eminence during the Ming and Ch'ing dynasties. They were able to produce in nearly every generation a highly placed government official who owed his success to high achievement on the imperial examinations. Through marriage politics, this second branch of the Chuang lineage had established relations with other important lineages in Ch'ang-chou—a sign of the emerging status of the Chuang lineage vis-à-vis other more established lineages in the area. The

[2] Ibid., pp. 405-20. On the Chuangs see Chu-chi Cbuang-shih tsung-p'u , partially unpaginated manuscript dated 1796, 2.1a-8a, 3.1a-2b. See also P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u , (1935), 12A.36a, and Wu-chin Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (ca. 1840), 16.25b. Uxorilocal marriage could create allies out of other powerful and wealthy families lacking a male heir. See James L. Watson, "Anthropological Overview," pp. 284-85, and Dennerline, "Marriage, Adoption, and Charity," pp. 173-74 (both articles appear in Kinship Organization in Late Imperial China , ed. Ebrey and Watson). Cf. Pas-ternak, "Uxorilocal Marriage in China," and Zurndorfer, "Local Lineages and Local Development," p. 33.

Chuangs could now define themselves within a community of prestigious affines built around strategic marriages.

The eldest daughter of Chuang Ch'i (1488-1566), for example, was married to Tang Shun-chih (1507-60), one of the most celebrated scholar-officials of the Ming period. In addition, Chuang Ch'i's grandson, Chuang I-lin, a major patriarch in the second branch of the Chuangs, married a woman from the T'ang lineage and was intimate with Tang Shun-chih, whose distinguished family belonged to one of the most important Ch'ang-chou lineages during the Ming dynasty. T'ang and Hsueh Ying-ch'i (1500-73) were influential in all aspects of Ch'ang-chou's cultural life and were mentors to many of the subsequent leaders of the Tung-lin movement in Wu-hsi County.[3]

T'ang Shun-chin was a leading Confucian whose interests ranged from literary pursuits to statecraft issues. He championed the role of the charitable estate in lineage organizations by appealing to the classical ideal of broadly based kinship solidarity.

The ancients relied on kin [tsu, lit., "patriline"] to establish kinship groups for them. Those kinsmen who had surplus wealth then returned it to the kindred, and those who could not provide sufficiently for themselves partook of the kindred's wealth. These kinsmen treated one another as parts of a single body, like bone and sinew, hand and foot. Their resources covered ali like digestive juices, overflowing into interstices, filling up only the empty places, and there was no depressed or swollen places, no excesses or deficiency. Thus, in the whole kin group there were no wealthy and no poor families. Moreover, no kin group under heaven was without a kindred, and in this way there were no wealthy or poor families in the empire. Isn't this what was meant by saying that when everyone treats relatives as relatives the empire is tranquil?[4]

As an ancient ideal, kinship solidarity had begun to fade when private interests, according to T'ang, had increasingly penetrated Chinese society:

Only after the demise of the well-fields [ching-t'ien ] were there means for ranking property in the village. Only after the demise of kinship regulations [tsung-fa ] were there means for ranking by property within the kin group. At

[3] Chu-chi Chuang-shih tsung-p'u (1796), 3.lb. See also P'i-ling T'ang-shih chia-p'u (1948 ed.), vol. 9, pp. 1a-1b (Wu-fen shih-piao ), and T'ang Shun-chih, Ching-chuan hsien-sheng wen-chi, 15.27a-31b, for bis epitaph for his wife from the Chuang lineage, who died in 1548. Cf. P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), 13.4a-5b, and Goodrich et al., eds., Dictionary of Ming Biography , pp. 619-22, 1252-56.

[4] T'ang Shun-chih, Ching-ch'uan hsien-sheng wen-chi , 12.24b. Cf. the translation in Dennerline, "New Hua Charitable Estate," pp. 45-47, and Wu-hsi Chin-k'uei hsien-chih (1881), 37.2a-3b.

the extreme there are cases where slave boys tire of meat and gravy while kinsmen grab for the ladle. The benevolent gentleman sympathizes and thereupon makes use of his position to create charity land to succor his kin. Thus, even though there is something that the great kindred bequeaths to them, yet as charity lands are established the term "great kindred" [ta-tsu ] is further obscured.

Ideals of ancient society, symbolized best by the well-field system canonized by Mencius, had declined to the point that T'ang Shun-chih admitted that kinship relations were by his time a pale shadow of the public-minded (kung ) values they once stood for. T'ang understood how the forces of commercialization and market specialization had affected idealized traditional values and transformed the context within which kinship values were expressed:

In essence, it is the case with charity land that it exists because there is a man of means, while under the kinship regulations [in antiquity] even the most valuable properties were shared, in the case of charity land, it is only the benevolent person as a part of the kin group who treats others in a public-minded manner [hsiang-kung ], while under [ancient] kinship regulations, even where the inheritance was small and niggardly, no one could treat others sparingly. Therefore, as a model, charity land leads to narrowness and one-sidedness, whereas the kinship regulations [of antiquity] lead to equity and universality.[5]

Nevertheless, T'ang continued to advocate an emphasis on distant agnates in order to reaffirm the primacy of kinship models from antiquity. Broadly based kinship relations were at least a means to overcome the contemporary suspicion of selfishness (ssu), when stress was placed on household and family line and not lineage group:

Still, since the understanding of the benevolent gentleman is already sufficient to attain this level, can the fact that no one shares his means with others really be owing to the differences between ancient and contemporary times? Might it not also be that charity land emanates from the ability of such a person to take responsibility upon himself, while [ancient] kinship regulations could only be imposed from above and never be established by joint responsibility.

Admitting the devolution of local power into the hands of gentry families and lineages, T'ang Shun-chih made the best of an irreversible process. If the communal ideals of the ancients could not be revived in contemporary sixteenth-century rural society, then well-intended

[5] T'ang Shun-chih, Ching-ch'uan hsien-sheng wen-chi , 12.24b-25a. See also Ku Yen-wu, Jih-chih-lu , pp. 649-55.

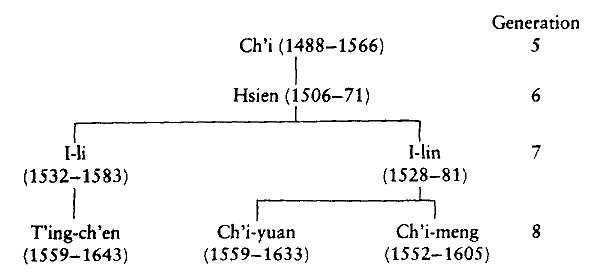

Fig. 5.

Major Segments of the Second Branch of the Chuang Lineage during the Ming Dynasty

kinship groups could at least approximate the classical ideal of equitable distribution of wealth through the creation of charitable land for their kin and descendents. T'ang was not speaking as a disinterested bystander. A key figure in the T'ang lineage in Ch'ang-chou with strong affinal ties to the Chuang lineage there, T'ang's views reflected the moral high ground on which late Ming lineages in the Yangtze Delta were taking a stand..[6]

The Chuangs' Rise to Prominence

The Chuangs' social climbing accelerated by the late Ming. The Chuang lineage, particularly its second branch, outstripped the T'ang name in prestige and influence in Ch'ang-chou (fig. 5). An analysis of the social milieu (in which the Chuangs first married their women into more elite gentry families and then received women from other less elite lineages such as the Lius [see below] as brides for their increasingly well-placed sons) reveals how the local standing of the Chuangs increased. Such social climbing also brought with it increased educational opportunities for Chuang women, which we shall discuss below. By the eighteenth century the marriage strategies of the Ch'ang-chou Chuangs were well entrenched, as families in the lineage successfully arranged prestigious links for both its sons and daughters.

In 1580 Chuang I-lin, one of the major scions of the second branch, saw to it that a genealogy was compiled for the Chuang lineage. This

[6] T'ang Shun-chih, 12.25a. See also Ebrey, "Early Stages," p. 40n.

event shows that the descent group had reached a major point in its development as a higher-order lineage. The Chuangs traced their line back to Chuang Hsiu-chiu, claiming shared estate property that had accrued through Chuang I-lin. Ancestral halls, sacrificial fields (the income from such lands financed the sacrificial rituals of ancestor worship), and updated genealogies were important elements in the development of lineage solidarity..[7]

Subsequent editions of the Chuang genealogy were compiled regularly—1611, 1651, 1699, 1761, 1801, 1838, 1883, and 1935. In addition, the Chuangs became a lineage whose most prestigious branches were urban-based, taking advantage of the city's economic and cultural advantages. The Chuangs' prestigious second branch, for example, was so urbanized that its two chief wings in Ch'ang-chou City were known as the "Eastern and Western Chuangs." Localized in Ch'ang-chou, the Chuangs could also include in their genealogy dispersed segments in nearby Lower Yangtze locales, as well as in Fu-chien and Kuang-tung..[8]

It would be inaccurate to see the emergence of the Chuangs in Ch'ang-chou simply as part of the segmentation within the kinship system, however. This perspective would overlook the historical conditions that underlay late Ming lineage formation. We need to be cognizant of the social situation within which lineages such as the Chuangs emerged. The Chuang lineage developed as part of the response of elite segments to the changing regional economy and the political turmoil surrounding the fall of the Ming dynasty. The Chuangs' successful response to these external nonkinship factors brought them increased prestige and prominence as a higher-order lineage. Just as the favorable economic climate of the late Ming encouraged lineage formation, the powerful organization the Chuangs had forged by the

[7] P’i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), 18B.36a-39a. The Chuangs developed a pattern of intermarriage with the Liu lineage in Ch'ang-chou, which we will discuss in more detail. See also, Ebrey, "Early Stages," pp. 55-56.

[8] Chu-chi Chuang-shih tsung-p'u , 1883 printed ed. pp. 8.29a-36a. See P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), pp. 1a-5b (1934 "Hsu" [Preface]), for mention of the various editions of the Chuang genealogy. See also ibid., 12A.40a, for discussion of the "Eastern and Western Chuangs." I have located and used the 1801 (through a 1796 manuscript version), 1838 (printed ca. 1840), 1883, and 1935 editions. For the urban-and rural-based Chuang lines, see Wu-chin Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (ca. 1840), 7.1a-2b, 8.49a-53b, 9.21a-26b, 13.1a-2b, 13.41a-43b. See in particular Chuang Ch'i-yuan's "Hsu" (Preface) to his Ch'i-yuan chih-yen, p. 10b. Other Chuang segments resided in Su-chou, Hang-chou, and Chia-hsing. See the ca. 1840 edition, 8.25a-41b. For Chuang segments in Fu-chien and Kuang-tung, see Chuang Yu-kung's 1761 "Hsu" (Preface) in P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), pp. 2a-2b.

seventeenth century helped them to compete for land, wealth, and power in Ch'ang-chou during the Ch'ing dynasty.

Before the fall of the Ming dynasty, lineages such as the Chuangs in Wu-chin had come to grips with the need for tax reform. Affinal relations with the prestigious T'ang lineage in Wu-chin via T'ang Ho-cheng (son of T'ang Shun-chih and his Chuang wife), who was one of the Tung-lin advocates of tax reform, implies that some Ch'ang-chou lineages were predisposed to accept tax reforms that had been championed during the Ming but not enacted until the Ch'ing. The alarming extent of special tax exemptions granted in Wu-chin County had been noted in the 1605 county gazetteer compiled under T'ang Ho-cheng's direction..[9]

Beginning in the fifteenth century tax exemptions were discussed within the context of long-term changes in Wu-chin land policy. Ch'ang-chou genealogies point to the interaction of several lineage groups and suggest that some lineage members supported late Ming calls for social and tax reform. The continuity of dominant lineage groups in local society from the Ming debacle to the Manchu triumph means that some gentry had successfully identified their interests in line with local reformist programs,.[10]

We see in chapter 1 that the Ming tax system was weakened by its granting of exemption to those who lived on official salaries. The burden of labor services was left squarely on the shoulders of commoners, who in addition to the land tax had to provide labor services to local officials. Tung-lin supporters in Ch'ang-chou Prefecture were acutely aware of this unfair situation. But in the sixteenth century T'ang Shun-chih, in addition to his concerns for kinship solidarity, had already prefigured the reform proposals of the Tung-lin partisans. In a letter directed to the Su-chou prefect, Wang Pei-ya, T'ang pointed to the link between secret trusteeship of land (kuei-chi ) and tax exemptions granted to gentry:

The practice of secret trusteeship by influential households is due to excessive exemptions granted to official households. These two ills are actually one. For example, an official who is entitled to exemptions on 1000 mou of land in a household but owns 10,000 mou, or who has no land but receives 10,000 mou under custody, will divide the 10,000 mou of land into ten

[9] Kawakatsu, Chugoku[*] hoken[*] kokka no shihai kozo[*] , pp. 209, 235-36, 336, 440-45. Nan-ching (Nan-chih-li) had also tried tax reform in the 1570s. For T'ang Ho-cheng's remarks see Wu-chin hsien-chih , preface.

[10] Beattie, Land and Lineage .

households. Therefore, with each 1000 mou receiving exemption in a household, the whole 10,000 mou are exempted from the labor service obligation,.[11]

T'ang Shun-chih's landsman and colleague Hsueh Ying-ch'i, also influential in Wu-chin County among the Tung-lin leaders, described the hardships faced by families. According to Hsueh, the labor services tax forced many of Ch'ang-chou's promising local talents to forgo their Confucian studies in order to fulfill the tax obligations incurred by their families. Many lower-level gentry-literati such as Liu Ta-chung in Wu-hsi County, among others, only made it as far as a licentiate (sheng-yuan, that is, license to participate in the local-level imperial examination) before the labor services tax compelled them to give up their studies. Liu Ta-chung had grown up with Hsueh Ying-ch'i and T'ang Shun-chih. But his father's early death meant that Liu was now shouldered with the sole responsibility for his mother and for performing the labor service his household owed. In his epitaph for Liu, Hsueh Ying-ch'i noted that such commitments had prevented his friend from matching the local and national acclaim garnered by friends Hsueh and T'ang..[12]

Late-sixteenth-century reform efforts in Ch'ang-chou Prefecture pivoted around the swelling inequities in local society. Labor tax obligations fell on households that could least afford them. Ch'ang-chou local leaders in the 1590s increasingly called for enaction of a system of land and labor equalization (chün-t'ien chün-i ), a successor to piecemeal reforms in the 1570s aimed at equalizing labor service obligations of taxable households. In the face of commoner opposition to the abuse of tax exemptions gentry-officials had granted their own households, Ou-yang Tung-feng (fl. ca. 1604), prefect in Ch'ang-chou, and Hao Ching, magistrate in Chiang-yin County, unsuccessfully called on gentry to help make up for deficiencies in the labor service rolls (t'ieh-i ). Hao Ching had been demoted to assistant magistrate in I-hsing County in Ch'ang-chou in 1599 after denouncing greedy imperial tax collectors. From 1600 to 1603 he served in Chiang-yin. We shall encounter Hao, a critic of Old Text Classics, later on. Ou-yang Tung-feng had close ties to the Tung-lin partisans in Wu-hsi and had helped protect the Lung-

[11] See Wiens, "Fiscal and Rural Control Systems," pp. 61-65. See also T'ang Shun-chih, Tang Ching-ch'uan hsien-sheng wen-chi , in Ch'ang-chou hsien-che i-shu, 10. 13b-14a.

[12] Hamashima, Mindai Konan[*] noson[*] shakai no kenkyu[*] , pp. 525-26. See also Hsueh Ying-ch'i, Fang-shan Hsueh hsien-sheng ch'üan-chi , 30.1a-3a.

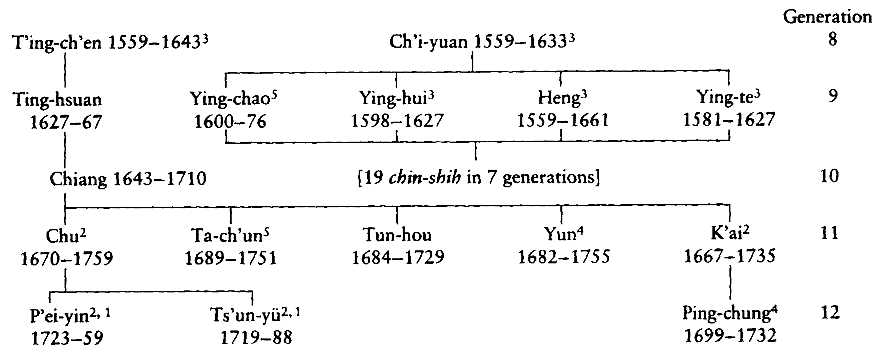

Key: 1 Grand secretary

2 Hanlin academician

3 Chin-shih

4 Chü-jen

5 Fu-pang : supplemental Chü-jen

Fig. 6.

The Second Branch of the Chuangs in Ch'ang-chou during the Late Ming and Early Ch'ing

ch'eng Academy in Wu-chin from repressive government policies against private academies.

Peasant and bond servant rebellions in the Yangtze Delta, and the resulting pressure to reform, continued, however. Beginning around 1611, provincial leaders simultaneously instituted tax relief in Su-chou, Sung-chiang, and Ch'ang-chou. These were the "big three" (Su-Sung-Ch'ang) prefectures in the Lower Yangtze, where agricultural commercialization and market specialization were most advanced. These reform efforts continued into the 1630s, which indicates that there was substantial entrenched gentry opposition to any curtailment of their privileged tax status.

Provincial and county pressure to institute a system of "equal labor for equal fields" was more successful in Ch'ang-chou Prefecture than in neighboring Su-chou and Sung-chiang. Hamashima Atsutoshi attributes Ch'ang-chou's relative success to the influence of Tung-lin supporters in Wu-hsi and Wu-chin counties. The gentry landlords there, such as Ku Hsien-ch'eng and Kao P'an-lung, maintained more enlightened views than their peers elsewhere in the Yangtze Delta-Lake T'ai area. We should also recall that the leaders in the Tang, and by implication the Chuang, lineage responded to the exploitive behavior of late Ming gentry by discouraging excesses among their kin and by putting their weight behind tax reform..[13]

Within this context, it is interesting that Chuang Ts'un-yü's great-great-great-grandfather Chuang T'ing-ch'en (fig. 6), who rose to a high position in the Ministry of Rites, had opposed proposals to establish shrines throughout China honoring Wei Chung-hsien, the eunuch-confidant of the T'ien-ch'i Emperor and archenemy of the Tung-lin school. When asked to lend his calligraphic hand to composing script for the engraved monuments of such shrines, Chuang T'ing-ch'en refused. Moreover, in his last years, just before the fall of Peking to the Manchus in 1644, T'ing-ch'en had been involved in the activities of the Lung-ch'eng Academy in Wu-chin County and the Su-chou-based Fu She movement, which had tried to keep the reformist policies and statecraft goals of the Tung-lin partisans alive.

Members of closely related lines in the Chuang lineage joined Ting-ch'en in participating in the emerging political societies of the late Ming. Although no evidence points to the direct participation of any

[13] Hamashima, Mindai Konan[*] , pp. 434-35, 486-89, 499-501. See also Goodrich et al., eds., Dictionary of Ming Biography , p. 503, and Beanie, "Alternative to Resistance," p. 249. Cf. Mori, "The Gentry," pp. 49-51.

members of the Chuang lineage in the meetings of the Tung-lin partisans in Wu-hsi and elsewhere in Ch'ang-chou Prefecture (Wu-chin, 1609; I-hsing, 1610), it is clear that Chuang T'ing-ch'en and others in the lineage knew that by opposing Wei Chung-hsien and his tax extortion they were siding with the Tung-lin party in its dangerous battle with the eunuch's faction at court. Moreover, T'ing-ch'en's son and grandson (Ting-hsuan and Chiang, respectively) refused to serve the Manchu Ch'ing dynasty out of loyalty to the Ming dynasty. It was not until Chuang Chu—T'ing-ch'en's great-grandson and Chuang Ts'unyü's father—that this segment of the second branch of the Chuang lineage reentered mainstream Confucian politics. Chuang T'ing-ch'en's opposition to Wei Chung-hsien and his participation in the Fu She become clearer when understood in the larger social milieu of Ch'ang-chou lineage relations and affinal ties..[14]

The Chuangs and the Ming-Ch'Ing Transition

The fall of the Ming dynasty to Manchu barbarians was a bitter experience for Lower Yangtze gentry, although the Manchu triumph, if anything, only enhanced what we are calling "gentry society." Once the winds of dynastic change had blown through, the demise of organizations centering on the Tung-lin and Fu She movements left lineage organizations intact as the major social mechanisms of local control. Local elites in T'ung-ch'eng, An-hui, for example, easily reestablished themselves during the Ch'ing dynasty. In fact, the dislocations wrought by the change of dynasties probably strengthened lineage organization and structure there.

Many of the large corporate lineages in eighteenth-century Kuang-tung Province came into existence only after the dislocations of the mid-seventeenth century. Ruble S. Watson has traced the elaborate "High Ch'ing" lineage organization to the era of prosperity that followed on the heels of the social turmoil of the seventeenth century. The enhanced local power of the Ch'ing elite, organized through higher-order

[14] P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), 12A.2a-4b. See also Wang Hsi-hsun's biography for Chuang Shu-tsu in Ch'ieh-chu-an wen-chi, p. 221, which links T'ing-ch'en's opposition to Wei Chung-hsien to Chuang Ts'un-yü's opposition to Ho-shen. Wang also notes that for two generations after T'ing-ch'en, his descendents did not serve the Ch'ing dynasty. On Wei and the shrines see Ulrich Mammitzsch, "Wei Chung-hsien," p. 250.

lineages, dates from, or was substantially expanded in, the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries..[15]

The Chuang lineage as a whole showed relatively little effect from the wars and economic dislocation brought on by the fall of the south in the 1640s, when invading Manchu armies, whose ranks were swollen with Chinese mercenaries, ended the Ming dynasty. As we have seen, some Chuangs retired to private life out of loyalty to the fallen Ming house. Despite this, the Chuangs (particularly Chuang Ch'i-yuan's line [see fig. 6]) went on in the new dynasty much as they had in the old. How could the Chuangs in Ch'ang-chou have survived relatively intact during the Ming-Ch'ing transition? As in T'ung-ch'eng, An-hui, the mid-seventeenth-century tax rebellions that threatened the elite's financial privileges in Ch'ang-chou forced lineage leaders to make important strategic decisions. To ensure local order and to reestablish their local preeminence, the elite had to accede to the new central power.

Tax reform programs associated with the Single-Whip policy (discussed in chapter 1 as part of the legacy of late Ming reformism) became state policy during the early Ch'ing. Although most of the elite opposed these reform programs during the late Ming, Ch'ang-chou Prefecture, particularly Wu-chin County, had conducted some of the most progressive experiments with tax reforms. As we have seen, the power of the Tung-lin partisans in their home counties meant that in Ch'ang-chou there was a more broadly based recognition among elites that tax reform was necessary.

It is ironic that reform policies advocated in the late Ming by the Tung-lin partisans, among others, were enacted in local society by the Ch'ing dynasty. According to Kawakatsu Mamoru, the Manchus needed to stabilize grain transport to the north, increase tax resources, and come to terms with local gentry influence in order to consolidate conquered territories. The new dynasty therefore undertook various measures, including efforts to equalize land and labor taxes. In addition, in 1657 the regulations for tax exemption were changed abruptly in an effort to curb the excessive tax privileges of the gentry. This change was given political teeth in the well-publicized legal arraignments of selected Yangtze Delta gentry in 1661-62 for back taxes owed

[15] For discussion of the fall of the south, see Dennerline, Chia-ting Loyalists . On the fall of Chiang-yin see Wakeman, "Localism and Loyalism." See also Struve, Southern Ming , pp. 1-14, 167-95; Ruble S. Watson, Inequality , pp. 6, 14, 22-24, 34-35, 174; and Beattie, Land and Lineage, pp. 44-48, 129, 267. Cf. Ray Huang, Taxation , pp. 147, 149; and Twitchett, "Fan Clan's Charitable Estate," pp. 128-29.

the state. The tax cases centered on the three prefectures of Su-chou, Sung-chiang, and Ch'ang-chou.

According to Frederic E. Wakeman, Jr., a compromise was reached between the Chinese landowning elite and the Manchu throne whereby gentry tax exemptions were restricted and Manchu military prerogatives were limited in favor of civilian rule. Reforms that a native Chinese dynasty could not push through because of local opposition were enacted by a conquering foreign dynasty. Problems pertaining to rural society were ameliorated through the force of arms..[16]

In its efforts to carry out tax reform, the Ch'ing state placed reform-minded lineages in a better position vis-à-vis their more conservative competitors to maneuver for local power and position. Lineages, for example, continued to play an important role in tax collection under Manchu rule, and the court relied on local gentry in many cases to effect the "equal service for equal fields" reforms below the county level. In return for such local support, the K'ang-hsi Emperor (r. 1661-1722) reaffirmed imperial support for lineage organizations and for the special tax status for charitable corporate estates.

It was no accident, then, that in Ch'ang-chou Prefecture the Chuang and Liu lineages became increasingly prominent in both local society and national affairs under the new dynasty. They represented local higher-order lineages that quickly renounced Ming loyalism in favor of recognizing and thereby exploiting the new social and political realities in place by the 1660s. Of course, an officially patronized elite family gained prestige within a kinship group over lower levels in its own network. In the process, kinship solidarity mitigated the taxing power of the state and helped keep landholding profitable. At the same time, traditional gentry prerogatives in local society were maintained in modified form..[17]

After the Ming debacle lineage members had to track down the lineage's scattered members and to recompile genealogies. Land left vacant had to be recovered and placed under new, more reliable management. By 1651 the Chuangs had completed the revision of their genealogy, and thereafter the most successful segments of the lineage continued their remarkable rise to local and national preeminence. The

[16] Mori, "The Gentry," pp. 52-53; Kessler, K'ang-hsi , pp. 33-39; and Wakeman, "Seventeenth-Century Crisis," p. 16. See also Kawakatsu, Chugoku[*] hoken[*] kokka , pp. 576-77; Beattie, "Alternative to Resistance," p. 263; and Meng, Ming-Ch'ing-shih lun-chu chi-k'an , pp. 434-52.

[17] Hsieh, Ming-mo Ch'ing-ch'u te hsueh-feng , pp. 79-80, discusses the modus vivendi reached between Manchu conquerors and Chinese landowners.

Chuangs soon became an elite lineage that fully accepted and thrived under the alien central government in Peking.

Two lines within the second branch, which emanated from Chuang T'ing-ch'en and Chuang Ch'i-yuan respectively (both became chin-shih in 1610) became so prominent during Ch'ing times that they can only be described as a literati factory for producing chin-shih degree-holders (see fig. 6). Chuang Ch'i-yuan's line produced nineteen chin-shih in seven generations, including three of his four sons. Nearly as productive was Chuang T'ing-ch'en's line, which produced Chuang Ts'un-yü in its eighth generation (counting from Chuang Hsiu-chiu)..[18]

Charitable estates remained in a privileged tax position after the tax cases of 1661-62. Lineage trusts helped keep scattered properties under unified control and protected those who shared in the trust from the inequities of the tax system. Such arrangements lasted into the middle of the eighteenth century, when abuse of lineage tax privileges again became a cause for concern. In 1756, for example, Chuang Yu-kung— then governor of Chiang-su Province in Su-chou—memorialized the throne concerning the sale of charitable estates by unscrupulous descendents. What disturbed Chuang Yu-kung was that the ideal of charitable land, which the state wholly supported, was being compromised. Chuang urged the Ch'ien-lung Emperor to harshly punish those who would manipulate lineage trusts for their private profit..[19]

Chuang Yu-kung, although not in the direct lines of descent of the four branches of the Ch'ang-chou Chuang lineage, represented a Chuang constituency in Kuang-chou that developed clan (that is, artificial kinship ties) relations with their Ch'ang-chou namesakes in the early seventeenth century. The Kuang-chou group traced its roots from southeast China (Fu-chien and Kuang-tung) back to Ch'ang-chou. By the 1750s Chuang Yu-kung and Chuang Ts'un-yü, representing their respective lineages, had reached the highest echelons of political power in the state. While Yu-kung served in Su-chou as governor (his jurisdiction included Ch'ang-chou Prefecture), Ts'un-yü in 1756 was academician of the Grand Secretariat (nei-ko hsueh-shih ) in the inner court. The Chuangs' Ch'ang-chou genealogy was then undergoing revision for its third edition, and Chuang Ts'un-yü prevailed upon Chuang Yu-kung as a Kuang-chou namesake to contribute a preface for it.

[18] Chu-chi Chuang-shih tsung-p'u (1883), 8.9b-10b, 8.14b-16a, 8.20b-21a.

[19] Chuang Yu-kung's memorial appears in Huang-Ch'ing ming-ch'en tsou-i, 50.18a-21a.

Published in 1761, Yu-kung's preface appealed to kinship solidarity as the basis for social order. When seen in the context of the sale of corporate land by profit-seeking opportunists, Yu-kung's preface underscores the importance of kinship ideals to the Chuangs, as public officials and lineage members. The betrayal of such ideals, said Yu-kung, warranted harsh punishment..[20]

The emperor eventually responded to the growing exploitation of kinship privileges. In a 1764 edict, for example, he decreed that only those lineage properties with legitimate ritual and relief functions could be incorporated as trusts and receive special tax status. Efforts to close the tax loophole did not challenge the belief that charitable estates, when properly organized for the sake of kin, provided legitimate protection from the tax system. The emperor noted:

In order to give importance to kinship groups and to cultivate affectionate feelings among their members, people established ancestral halls to perform annual sacrificial rites. If indeed these halls are located in native villages or cities inhabited by kinsmen, all of whom are blood relatives of the same lineages, [these halls] are not only permitted by law but are encouraged as constituting a good custom..[21]

The steady rise to prominence of the Chuang lineage in Ch'ang-chou provides a window on the long-term social and economic changes we have presented. Through farsighted lineage strategies, gentry interests dealt successfully both with the crises in late Ming rural society in the Yangtze Delta and with the Manchu triumph in south China in the mid-seventeenth century. The success of the Chuang lineage in surviving the Ming-Ch'ing transition and in increasing its prominence both in Ch'ang-chou and in Peking's elite bureaucratic circles during the Ch'ing dynasty suggests that kinship strategies during the seventeenth century played a significant role in defending elite interests in local society.

The Chuangs as a Professional Elite

During the Ch'ing dynasty the Chuang lineage became the most important intellectual force (if success is measured by achievement in the ira-

[20] P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), pp. 2a-2b (table of contents). See also Ch'ing-tai chih-kuan nien-piao , vol. 2, pp. 975, 1414.

[21] Ta-Ch'ing hui-tien shih-li , 399.3b. On the Ch'ien-lung Emperor's reaction to lineage excesses, see Hsiao, Rural China , pp. 348-57, where portions of the 1764 edict are translated.

perial civil service examinations) in the prefectural capital of Ch'ang-chou. For the Ch'ing period alone, the Chuang lineage had a total of ninety-seven degree holders, compared with a total of seven during the Ming dynasty. The lineage was accorded the further honor of twenty-nine chin-shih, compared with only six during the Ming, earning eleven places on the Hanlin Academy. Five of the latter came from Chuang Ts'un-yü's immediate family. From 1644 until 1795 a total of thirty-four Hanlin academicians came from Wu-chin County. Nine of these (26 percent) were from the Chuang lineage, and four (12 percent) from Ts'un-yü's line.[22]

In three generations, from his father to his sons, Ts'un-yü's family produced eight chin-shih and four chü-jen. In six generations, beginning in the late Ming, the line had nine chin-shih. Using Ping-ti Ho's figures for the total number of chin-shih in Ch'ang-chou Prefecture during Ch'ing times (618), we find that the Chuangs received 4.7 percent of that total. If the combined figures for Wu-chin and Yang-hu counties (the latter was separated from Wu-chin in 1724) are used (265), then the Chuang lineage accounted for more than 11 percent of the total number of chin-shih there during the Ch'ing dynasty.[23]

An inordinate number of this line in successive generations were appointed to the Hanlin Academy, the highest academic honor that could be conferred on successful chin-shih examination candidates and the ticket to high office (fig. 7). Chuang Ts'un-yü's father, Chuang Chu, and uncle Chuang K'ai were so appointed, as were Ts'un-yü and his younger brother P'ei-yin—the latter optimus (chuang-yuan ) on the 1754 palace examination. Ts'un-yü had had the distinction of achieving secundus (pang-yen ) on the 1745 palace examination. This remarkable run continued when Ts'un-yü's son, T'ung-min, finished near the head of the palace examination of 1772 and was also appointed to the Hanlin Academy. Another son, Hsuan-ch'en, finished high on the 1778 palace examination. Chuang P'ei-yin's son, Shu-tsu, passed the palace examination in 1780, and Ts'un-yü's great-great-great-nephew Shouch'i was also appointed to the Hanlin Academy in 1840.[24]

[22] See P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), 9.1a-8a, especially 9.19b-20a, for a list of all members of the Chuang lineage who were successful on the examination system. A list of Hanlin academicians from the lineage is also included. Cf. Lui, Hanlin Academy, pp. 132-33. Figures include those for Yang-hu County, which was separated from Wu-chin County in 1724.

[23] Ping-ti Ho, Ladder of Success , pp. 247, 254.

[24] On the Hanlin Academy, see Lui, Hanlin Academy .

Key:

1 Grand secretary

2 Hanlin academician

3 Chin-shih

4 Chü-Jen

5 Fu-pang : supplemental Chü-jen

Fig. 7.

Major Segments of the Second Branch of the Chuang

Lineage in Ch'ang-chou during the Ch'ing Dynasty

Success in the Imperial Bureaucracy

Interestingly, the Chuang's success at the Hanlin Academy became a crucial feature of their rise to national prominence. After placement in the Hanlin Academy, a member of the academy could normally expect an appointment in the Ministry of Rites as the logical next step in his career. Although the name "Ministry of Rites" sounds peripheral, in imperial China its ministers and functionaries were on center stage. The Bureau of Ceremonies, for example, was charged, as its name suggests, with all ceremonial affairs, which included administration of the National university (Kuo-tzu chien ) system, as well as supervision of the nationwide civil service examination system from the county, prefecture, and provincial levels to the national level in Peking. Hence the Ministry of Rites controlled the imperial education system. In addition, the Bureau of Receptions (Chu-k'e ch'ing-li-ssu ) was charged with the management of foreign relations under the traditional tributary system in effect since the Han dynasties.

In other words, the Ministry of Rites had as its portfolio two major functions of government: education and foreign affairs. Confucian classical training, inculcated through the rigorous examination system, was applied in the arena of foreign affairs. Hanlin academicians had priority in appointments dealing with these aspects of government.

By taking care of both imperial sacrifices in the Bureau of Sacrifices (Tz'u ch'ing-li-ssu ) and imperial family matters in the Imperial Clan Court (Tsung-jen fu ) under the Bureau of Ceremonies, the Ministry of

Rites had the further distinction of being the only ministry that was a member of the inner court of the emperor while remaining a full-fledged member of the outer court bureaucracy. It thus had access to the inner sanctum of imperial power and could effect its policies through the education bureaucracy down to all county levels outside Peking.[25]

Important members of the inner court during the Ch'ing dynasties came from the Hanlin Academy, the Grand Secretariat (Nei-ko ), and the Grand Council (Chün-chi-ch'u ). After the first Ming emperor Chu Yuan-chang had reduced the power of the state bureaucracy by doing away with all key leadership posts in the bureaucracy, personal secretaries to the emperor, known as "grand secretaries" (Ta-hsueh-shih ) increasingly took on the job of coordinating and supervising the six ministries. Because it straddled the middle ground between inner and outer echelons of power, the Ministry of Rites became more and more important.

When later Ming emperors, particularly during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, delegated much of their authority to members of the inner court, the links between grand secretaries and the Ministry of Rites became more intimate, and produced career patterns of major political and institutional consequences, not only for the Ming but also for the Ch'ing bureaucratic system. The doyen of the Ch'ang-chou New Text school of Confucianism, Chuang Ts'un-yü, exemplified this trend in the eighteenth century. This is to say that the Ministry of Rites provided more grand secretaries than any other ministry. Close links between the Ministry of Rites and Grand Secretariat had another distinctive feature: most grand secretaries had also been members of the Hanlin Academy early in their official careers. Out of a total of 165 grand secretaries during the Ming, 124 (75 percent) had been members of the Hanlin Academy.[26]

Moreover, 109 out of these 165 grand secretaries (66 percent) had also served in the Ministry of Rites, and 93 of the latter (56 percent of 165) went directly from the Ministry of Rites to the Grand Secretariat. What we see emerging in Ming political life is the remarkable convergence of the Hanlin Academy, Ministry of Rites, and Grand Secretariat. In a typical Ming-Ch'ing bureaucratic career, then, a successful graduate (normally with high honors) of the capital examination (chin-shih )

[25] Yun-yi Ho, Ministry of Rites, pp. 60-75.

[26] Von der Sprenkel, "High Officials of the Ming," pp. 98-99. See also Ho, Ministry of Rites , p. 16, and Ku, "Career Mobility Patterns."

was first appointed to the Hanlin Academy, where he served the court as a compiler or editor, or as a personal secretary to the emperor. From there he went on to serve in a variety of possible positions but eventually became a fixture in the Ministry of Rites, often as a capital or provincial examination official supervising the examination system.

The Ministry of Rites, then, served as a springboard for promotion to the Grand Secretariat, which until the emergence of the Grand Council remained the highest advisory body in the state apparatus. Those who spoke for the state in the name of the emperor were, for the most part, the top-ranking graduates of the highest-level examinations. The latter had served initially as apprentices in the proximity of the emperor through placement in the Hanlin Academy and Ministry of Rites.[27]

Cultural Resources and Political Prestige

Such highly placed members within the lineage meant that Ts'un-yü's family assumed a leadership role in the lineage from the late Ming until the late Ch'ing—a period of three centuries. Because only the wealthy and classically literate segments were responsible for lineage ritual and worship, ordinary members would not be directly involved in managing ancestral halls, organizing rituals, or allocating funds derived from charitable estates. The eminence of Ts'un-yü's family line thus overrode considerations of seniority. Within its own segment, Ts'un-yü's line brought its national and local prestige and influence to bear on its position as gentry spokesmen for the Chuangs in the Ch'ang-chou social and cultural world. In effect, the Chuangs became a "professional elite" of office-holding families, specializing in government service for generations.[28]

Of the four branches of Ch'ang-chou Chuangs, the second had superior prestige vis-à-vis the other three, but not seniority. The two lines emanating from Chuang T'ing-ch'en and Chuang Ch'i-yuan were clearly dominant within the second branch. When, for example, Chuang Ts'un-yü served concurrently in the Hanlin Academy, Ministry of Rites, and Grand Secretariat in the Peking imperial establishment, he became a local figure of immense prestige in his place of birth—prestige that accrued to his family, branch, and lineage in Ch'ang-chou.[29]

[27] Ho, Ministry of Rites , pp. 16-19. See also Lui, Hanlin Academy , pp. 29-44.

[28] Hartwell, "Demographic Transformations of China," pp. 405-25.

[29] Freedman, Lineage Organization , pp. 67, 69; Rubie S. Watson, Inequality , p. 27; and James L. Watson, "Chinese Kinship Reconsidered," pp. 608-12.

The unparalleled academic success of the Chuang lineage in the imperial examination system can be directly tied to its private lineage school, known as the Tung-p'o Academy. The school was named after the great Sung dynasty Confucian and man of letters Su Shih, who had visited Ch'ang-chou during his travels through south China. Su purchased property in Ch'ang-chou and had hoped to retire there. In fact, he died in Ch'ang-chou after being recalled from exile on Hainan Island.

Success on the examination system required a classical education. A rich and prestigious lineage could nearly assure such success by pooling its resources, establishing a school, and hiring qualified teachers. Coming from a family in a lineage with a strong tradition of scholarship, coupled with sufficient financial resources to pay for the protracted education in the Confucian Classics, Chuang Ts'un-yü and his family were blessed with rare advantages.

Among elite lineages in the Lower Yangtze, however, private lineage schools were common enough. The phenomenal success of the Chuang lineage on the examinations most likely points to the quality of its private preparation course and curriculum; the Chuang lineage school was probably more rigorous and demanding than similar schools in Ch'ang-chou and elsewhere. In addition, the Chuangs had become so well placed in local and national affairs as a result of earlier examination success and affinal relations that success, tinged with favoritism, fed on success.[30]

Not only males but also females, who stood outside the patrilineal system of descent, benefited from the educational facilities provided by wealthy lineages in traditional Chinese society. Lacking freedom of movement and barred from the official examinations and any possibility of holding political office, women in scholarly families were nonetheless often well-versed in literature and the arts. The Chuang lineage in Ch'ang-chou, by way of example, was famous for its female poets.

Including women who married into the lineage, Hsu K'o has counted twenty-two female poets of note from the Chuang lineage during the Ch'ing dynasty. Among these were Chuang Ts'un-yü's second daughter and Chuang P'an-chu, who was perhaps the best-known female poet from the area in the eighteenth century. The important function of poetry and the arts in gentry cultural life allowed both men and

[30] On lineage schools see Rawski, Education and Popular Literacy , pp. 28-32, 85-88. On Su Shih see Hatch's biography in Sung Biographies , vol. 2, pp. 954, 966-67.

women from prestigious lineages to spend their leisure moments in aesthetic pursuits.[31]

It was in the interest of a lineage and its long-term mobility strategies to provide facilities for the education of its talented members. Thus, the Chuangs, like most powerful lineages, guarded their scholarly traditions very carefully. Success of lineages often hinged on success in the examination system more than anything else. Philanthropic and charitable aspects of higher-order lineages, however, frequently meant that such private strategies for education were also complemented by more public-minded concerns, which derived from the public rhetoric used by kinship groups to legitimate their local activities.

For instance, outsiders such as the Han Learning scholar Hung Liang-chi were occasionally permitted, as young men, to study briefly with the Chuangs. With the death of his father, Hung, then only six years old, and his mother (née Chiang) were left very poor in Ch'ang-chou. One of his teachers at his mother's lineage school came from the Chuang lineage. In addition, Hung's mother had a sister who had married into the Chuang lineage. These links enabled Hung to study with several Chuang children his own age. So, in 1762 Hung was busy reading both the Kung-yang and Ku-liang commentaries to the Spring and Autumn Annals in the Chuang lineage school. Hung Liang-chi's eldest son later married a woman from the Chuang lineage, the daughter of Chuang Yun, a descendent in Chuang Ch'i-yuan's prestigious line..[32]

Another Ch'ang-chou native who benefited from Chuang lineage largesse was the k'ao-cheng historian Chao I. In his biography for Chuang Ch'ien written after Chao had gone on to fame and fortune in the Hanlin Academy after passing the chin-shih examination of 1761, Chao wrote of the help he had received from the Chuangs to further his studies. Chao I's granddaughter later married into the Chuang lineage.

Similarly, Liu Feng-lu, whose family and lineage had long been affinally tied to the Chuangs (see below), also received help in his early studies from the Chuang lineage. Because his mother, Chuang T'aikung, was a typically well educated Chuang woman, daughter of Chuang Ts'un-yü, Liu was permitted to study with the Chuangs. At an early age, he impressed his grandfather with his abilities in classical

[31] Hsu, Ch'ing-pai lei-ch'ao , 70/162. See also Ruble S. Watson, Inequality , p. 134; Chang, "Ch'ing-tai Ch'ang-chou tz'u-p'ai yü tz'u-jen," p. 134.

[32] Hung, Hung Pei-chiang ch'üan-chi , pp. 2b, 5a-5b. See also Hung's epitaph for his aunt in P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), 13.13b-14a, in which he notes that his aunt frequently took him to the Chuang lineage school. Cf. the 1935 genealogy, ibid., 18B.38b, and 19.26, and Chu-chi Chuang-shih tsung-p'u (1883), 7A.17b.

studies. In this manner, the Chuang lineage could demonstrate that it was fulfilling its public obligations to the larger community while at the same time benefiting kin.[33]

Lineage schools, particularly high-powered ones, were therefore schools in both the institutional and scholarly sense. The Chuang "school" represented a tradition of learning passed down within the lineage itself by its distinguished members and examination graduates. The special theories or techniques of a master, passed down through generations of disciples by personal teaching (which usually demarcated a "school"), could take place in a conducive social and institutional setting provided by a dominant agnatic descent group. The Ch'ang-chou New Text "school" was actually an eighteenth-century version of the Chuang tradition in classical learning, a tradition that drew on the distinguished place held by the Chuang lineage in Ch'ang-chou society since the seventeenth century.

Affinal Relations: The Lius and the Chuangs

As formidable as the Chuang lineage had become by the eighteenth century, its strength and influence was not based on kinship solidarity alone. Marriage strategies and descent were both used by elite households to serve their larger social and political ends. Alliance with other powerful families and lineages complemented kinship solidarity. The Chuangs thus developed close external affinal ties with the Liu lineage in Ch'ang-chou. Although prominent scholar-officials often preferred to build social networks based on more than local kinship, lineage organization, particularly through affinal ties, nevertheless remained a prominent feature in elite life. In the cases of the Chuangs and Lius, we can see how broader national level networks overlapped with local level lineage organizations and their interrelation in national and local politics.[34]

Unlike the Chuangs—whose migration to the Yangtze Delta can be

[33] See P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), 18B.39a, and Chu-chi Chuang-shih tsung-p'u (1883), ts'e 10, pp. 25a-26b. Liu Feng-lu's mother wrote a collection of poetry and took charge of her son's early literary training. See Wu-chin Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1929), 8.14a.

[34] James L. Watson, "Chinese Kinship Reconsidered," pp. 616-17. See also Ebrey, "Early Stages," p. 40n, and Hymes, "Marriage in Sung and Yuan Fu-chou," pp. 95-96 (both articles are published in Ebrey and Watson, eds., Kinship Organization ). Hymes cautions against overly contrasting strategies of alliance and descent. Cf. Dennerline, Chia-ting Loyalists , pp. 104-11, 113, for different views.

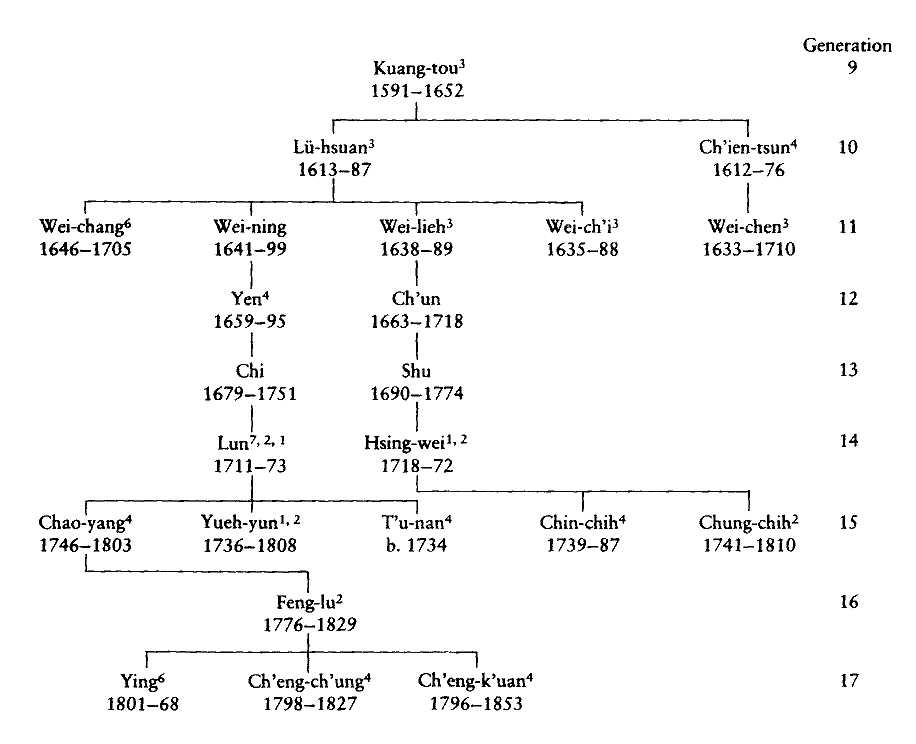

Fig. 8.

Major Segments of the Liu Lineage in Ch'ang-chou during the Ming Dynasty

traced to the twelfth-century advances of the Jurchen forces in north China—the Lius traced their origins in Ch'ang-chou to the mid-fourteenth century and the social and political convulsions that overtook the Lower Yangtze when rebel forces rose against Mongol rule. Contending armies struggled against Mongol forces and among themselves for control of the lucrative resources of the Mongol empire's richest region. One of these armies, led by Chu Yuan-chang, succeeded in establishing the Ming dynasty in Nan-ching in 1368.

Liu Chen, a native of the northern town of Feng-yang in He-nan Province, arrived in Ch'ang-chou Prefecture in 1356 in the service of one of the armies allied with Chu Yuan-chang. After aiding in the pacification of Ch'ang-chou, Liu stayed on for a decade, marrying and raising a son, Liu Ching. In 1366-67, Liu Chen left Ch'ang-chou to participate in military campaigns in Shan-hsi, leaving behind his son, who remained in Ch'ang-chou and transmitted the Liu family line in local society there. Although a military epochal ancestor for the Lius, Liu Chen never returned to Ch'ang-chou. Later investigations by the Lius in Ch'ang-chou revealed that Liu Chen had established yet another Liu family in Ta-t'ung, Shan-hsi, after he left Ch'ang-chou (fig. 8).[35]

Liu Ching passed the provincial chü-jen examination in 1400 and served as a county magistrate during the early fifteenth century, bringing the Lius to prominence in Ch'ang-chou society. His son, Liu Chün in turn became the chief ancestor for the three major branches of the Liu lineage in Ch'ang-chou, and the lineage became increasingly important in the late Ming. By comparison to the T'ang and Chuang lineages,

[35] Wu-chin Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1929), 1.13a, 3.la, and Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1792), 2.1a-b.

however, the Lius were relative newcomers in Ch'ang-chou. They did not become prominent in elite local circles until, in the eighth and ninth generations, the first and second branches produced a distinguished crop of scholar-officials.

In the eighth generation, Liu Ch'un-jen, of the main branch (ta-fen ), became the first of the lineage to pass the national chin-shih examination, finishing eighteenth in the competition of 1592. Liu Ch'un-jen's sons, along with those of his younger brother Ch'un-ching (direct ancestor of Liu Feng-lu), counted among their ranks two chin-shih, one chü-jen, and two tribute students (kung-sheng; nominees of local schools for advanced study and subsequent admission to the civil service). The ninth generation was conspicuous for producing three imperial censors (yü-shih ) during the late Ming: Liu Kuang-tou (son of Liu Ch'un-ching); Liu Hsi-tso (son of Liu Ch'un-jen); and Liu Hsien-chang (son of Liu K'e-ch'ang), a member of the second branch of the lineage (fig. 9).[36]

Liu Hsien-chang, for example, had taken his chin-shih degree in 1637 and was politically active in the late Ming, participating in the meetings of the Fu She activists. Liu Hsi-tso, in addition to his government service, had begun a pattern of marriage alliances with the Chuangs in Ch'ang-chou by marrying his daughter to Chuang Yin (1638-78), son of Chuang Ying-chao in the prominent ninth generation of the second branch of the Chuangs (see list). Hsi-tso's younger brother, Liu Yung-tso, was among those who participated in the Tunglin movement. The intermarriages continued as follows (generation number is in brackets):

Liu | Chuang |

Hsi-tso's [9] daughter | m. Yin [10] |

I-k'uei [10] | m. daughter of Yu-yun [10] |

Lü-hsuan's [10] daughter | m. Tou-wei [12] |

Yü-i's [11] mother | née Chuang |

Wei-ning's [11] daughter | m. Pien [11] |

Hsueh-sun [13] | m. daughter of Ch'u-pao [13] |

Hsing-wei's [14] daughter | m. Fu-tan [15] |

[36] Wu-chin Yang-hu hsien ho-chih (1886), 17.44a. See also Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1876), 8.18a, 8.33a.

Lun's [14] son | m. daughter of Ts'un-yü [12] |

Lun's [14] granddaughter | m. Ch'eng-sui [14] |

Chung-chih's [15] granddaughter | m. Ch'ien [16] |

Chao-yang's [15] daughter | m. Ch'eng [15] |

Another important member of the pivotal ninth generation of the Lius (in the second branch) was Liu Han-ch'ing, who took his chü-jen degree in 1642 and became a chin-shih in 1649. Before his death, Liu Han-ch'ing compiled the first genealogical record of the Liu lineage, which was completed in 1689. Six subsequent revisions were made in 1693, 1750, 1792, 1855, 1876, and 1929. Han-ch'ing's son, Liu I-k'uei, married the eldest daughter of Chuang Yu-yun, who was Chuang Ying-chao's eldest son. We should add that Han-ch'ing's great-uncle Liu Ying-ch'ao earlier had arranged for a marriage between his eldest daughter and Chuang Heng, Chuang Ying-chao's elder brother. Thus, by the early Ch'ing dynasty, the seventh and eighth generations of the Lius and the ninth and tenth generations of the Chuangs had developed close marriage ties.[37]

Liu Kuang-tou, in the main branch of the lineage, passed the chü-jen examination in 1624 (fig. 10). The following year he took the chin-shih degree in Peking. Involved in the up and down, factional nature of late Ming politics during the Tung-lin party's efforts to gain control of the imperial bureaucracy, Liu was appointed imperial censor, subsequently dismissed, and then reappointed as censor during a period of extreme bureaucratic corruption. Kuang-tou's examination success and high office—as important as they were in promoting his official career and the fortunes of the Liu lineage during the late Ming—were overshadowed by his remarkable behavior when Manchu armies, filled with Chinese mercenaries, launched their invasion of Ch'ang-chou in 1645.[38]

As a Ming dynasty censor, Liu Kuang-tou was bound by traditions of loyalty to the dynasty he served. The generation of 1644, which witnessed the demise of a native Chinese dynasty, had an established

[37] Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1792), 2.1a-13a, 4.1a-2a, 4.14a-14b; (1876), 1.36b, 2.1a-2b, 4.1a-2a; Chu-chi Chuang-shih tsung-p'u (1883), 5.34b, 5.43a-44b, 5.46b-47a; and Wu-chin Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1840), 3.20b. See also Chuang Chu, P'i-ling k'e-ti k'ao , 1.17b, 8.33a. Cf. Chin Jih-sheng, Sung-t'ien lu-pi, ts'e 1, p. 14a; Wu-chin Yang-hu hsien ho-chih (1886), 24.48b-49a; and Crawford, "Juan Ta-ch'eng."

[38] Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1792), 2.13a-14a. See also Crawford, "Juan Tach'eng," p. 42.

Key: l Grand secretary

2 Hanlin academician

3 Chin-shih

4 Chü--jen

5 Fu-pang: supplemental Chü-jen

6 Tribute student

Fig. 9.

Major Segments of the First and Second Branches of the Lius during the Ming Dynasty

Key: 1 Grand secretary

2 Hanlin academician

3 Chin-shih

4 Chü-jen

5 Fu-pang: supplemental Chü-jen

6 Tribute student

7 Grand counselor

Fig. 10.

Major Segment of the Main Branch of the Liu Lineage during the Ch'ing Dynasty

ideology of "not being a servant of two dynasties" (pu erh-ch'en ). This ideology forbade an official—even a subject—in one dynasty to serve in another. Ming loyalists, who remained influential for the remainder of the seventeenth century, expressed their dissent through the Confucian imperative of loyalty..[39]

In contrast to celebrated Yangtze Delta Ming loyalists such as Ku Yen-wu and Huang Tsung-hsi, however, Liu Kuang-tou was among the first Confucian officials in the Lower Yangtze to urge submission to the conquering Manchus. Unlike the grandson (Liu Ch'ao-chien) of his cousin Liu Hsi-tso, who went into seclusion after the Ming collapse in south China, Liu Kuang-tou urged the surrender of the Chiang-yin county seat in Ch'ang-chou Prefecture, which became, along with Yang-chou and Chia-ting, a symbol of Ming resistance to the invading armies. Chiang-yin loyalists chose instead to hold out. Thousands perished when mercenary armies brutally subdued and sacked the city.

Victimized by late Ming factionalism, Kuang-tou seems to have had few qualms about deserting the Ming banner. Moreover, because Ming loyalist forces labeled him a traitor after the fall of Chiang-yin, Liu was quickly appointed county magistrate in Chiang-yin by Manchu authorities in the Yangtze Delta. Later he served the new Ch'ing dynasty as pacification commissioner (an-fu shih ) in his home area of Ch'ang-chou Prefecture. It is intriguing that Liu Kuang-tou became associated under Manchu rule with the reform policy of "equal service for equal fields" in Ch'ang-chou, a policy that late Ming reformers had been unable to implement..[40]

Whatever the ethical implications of Kuang-tou's behavior, the Liu lineage in Ch'ang-chou benefited for the duration of the Ch'ing dynasty. Liu Kuang-tou's line in the main branch of the lineage assumed central importance in lineage affairs, and in almost every succeeding generation, the Lius produced a scholar-official of national and local prominence.

Kuang-tou's son, Liu Lü-hsuan, for instance, took his provincial degree in 1642 and passed the capital examination of 1649, surviving the dynastic change barely missing a rung in the bureaucratic ladder of

[39] Mote, "Confucian Eremitism."

[40] See Wakeman's poignant account of Chiang-yin's fall entitled "Localism and Loyalism," pp. 43-85, esp. p. 54, for a discussion of Liu Kuang-tou. Hamashima, "Mim-matsu Nanchoku no So-So -Jo[*] sanfu ni okeru kinden kin'eki ho[*] ," pp. 106-108, discusses tax reform efforts during the Ming-Ch'ing transition. See also Wu-chin Yang-hu hsien ho-chih (1886), 28B.7b, and Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1876), 2.27a. Cf. Li T'ien-yu, Ming-mo Chiang-yin Chia-ting jen-min te k'ang-Ch'ing tou-cheng , pp. 16-34.

success. Similarly, Liu Han-ch'ing took his chü-jen degree in 1642 under Ming dynasty auspices; he had few hesitations in competing, successfully, for chin-shih status in 1649 under Manchu jurisdiction. Liu Kuang-tou's reputation as a turncoat and his sons' examination success under two dynasties did not ruin the status of the Lius in local society either. Lü-hsuan gave the hand of his eldest daughter to Chuang Tou-wei, a member of the twelfth generation of the prominent second branch of the Chuangs and grandson of Chuang Ch'i-yuan. Although some Chuangs were Ming loyalists, such matters were of secondary importance in the advancement strategies of the Lius and Chuangs..[41]

Both the Chuangs and Lius had come through the Ming-Ch'ing transition remarkably intact and relatively unaffected by ideological commitments to the fallen Ming dynasty. Only slightly less successful than the Chuangs in the examination system, Liu Kuang-tou's line could count ten chin-shih from the ninth through sixteenth generations. There were an additional nine chü-jen graduates in generations nine through eighteen. Among these nineteen officials, the Lius could point to five Hanlin academicians, three grand secretaries, and one grand counselor (see fig. 10).

The intermarriage between the two lineages, as we have seen, was already important during the Ming-Ch'ing transition. Arranged marriages were common during the Ch'ing dynasty, no doubt in part to solidify the local position of the Chuangs and Lius as gentry who had switched rather than fought. The high incidence of such intermarriages, from the ninth to fifteenth generations of the Lius and from the tenth to the sixteenth generations of the Chuangs, signals an intimate relation of affines that carried over from Ch'ang-chou local society to the inner sanctum of imperial power in Peking..[42]

In the tenth generation, the main branch of the Liu lineage began to place sons in the upper levels of the imperial bureaucracy. Beginning with the eleventh and twelfth generations, the Lius were honored with Hanlin Academy graduates. By the fourteenth generation, the Lius had "arrived," placing sons of that generation in the Grand Council and Grand Secretariat. They reached the pinnacle of national and local prominence by the middle of the eighteenth century, coinciding almost

[41] Chuang, P'i-ling k'e-ti k'ao , 8.7a, and Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1792), 2.13b-14a; (1876), 4.14a-14b. See also Wu-chin Yang-hu hsien ho-chih (1886), 24.84a-84b, Chu-chi Chuang-shih tsung-p'u (1883), 7.22b, and P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), 1.23b, 3.25.

[42] Cf. Dennerline, "Marriage, Adoption, and Charity," p. 182.

exactly with the prominence of the Chuangs. Moreover, the key players in the Lius' and Chuangs' dual rise to power had affinal ties of great strategic importance, both for career advancement and as a guarantee for future success of the lineages..[43] The role of the two families from 1740 to 1780 may be summarized as follows (generation number is in brackets):

Chuangs | Lius |

Ts'un-y.ü [12] | Yü-i [11] |

Hanlin | Grand Secretariat |

Grand Secretariat | |

P'ei-yin [12] | Lun [14] |

Hanlin | Hanlin |

Grand Council | Grand Secretariat |

Grand Council | |

Yu-kung (from Kuang-chou) | Hsing-wei [14] |

Grand Secretariat | Hanlin |

Governor-general (Chiang-su) | Grand Secretariat |

Liu Yü-i, a chin-shih of 1712, was the first Liu from Ch'ang-chou to reach the Grand Secretariat. An eleventh-generation member of the second branch (erh-fen ) of the Lius, Yü-i served in the Hanlin Academy, where he worked on the Neo-Confucian compendium entitled Hsing-li ta-ch'üan (Complete collection on nature and principle) before holding the position of assistant grand secretary from 1744 until 1748. His mother came from the Chuang lineage. Liu Lun and Liu Hsing-wei, cousins in the main branch of the lineage that traced its prominence back to Liu Kuang-tou, took their chin-shih degrees in 1736 and 1748 respectively..[44]

Liu Hsing-wei, whose great-grandfather Wei-lieh and great uncles Wei-ch'i and Wei-chen had all been eleventh-generation chin-shih, served first in the Hanlin Academy. In 1765 he served as grand secretary in the Imperial Cabinet, along with Chuang Ts'un-yü who had been a grand secretary (in his second term) since 1762. Liu Hsing-wei's daughter was married into the Chuang lineage when she became the wife of Chuang Fu-tan, who was granted chü-jen status on the special

[43] Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1876), 2.80a-87b.

[44] Ch'ing-tai chih-kuan nien-piao , vol. 1, pp. 49-51, and Wu-chin Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1929), 4.16b.

examination of 1784 administered during the Ch'ien-lung Emperor's last southern tour. In addition, Hsing-wei's son, Liu Chung-chih, was admitted to the Hanlin Academy after passing the chin-shih examinations with honors in 1766. Chung-chih's granddaughter married Chuang Ch'ien, another in the prestigious second branch of the Chuang lineage, further cementing affinal ties between the Lius and Chuangs..[45]

Liu Lun's rise to prominence began when he finished first among more than 180 candidates on the special 1736 po-hsueh bung-tz'u examination ("broad scholarship and extensive words"; that is, qualifications of distinguished scholars to serve the dynasty) to commemorate the inauguration of the Ch'ien-lung Emperor's reign. Liu was subsequently appointed to the Hanlin Academy where he worked on a successive series of prestigious literary and historical projects, including compilation of the Veritable Records (Shih-lu ) of the preceding K'ang-hsi Emperor.

After serving as Hanlin compiler, Liu Lun's duties shifted from scholarship to politics. He rose to the presidency of a number of ministries after his appointment to the Grand Secretariat from 1746 to 1749. Liu Yü-i was concurrently an assistant grand secretary. In 1750 Lun was promoted to the Grand Council, where he served for much of the remainder of his career. As a grand counselor, Liu Lun was involved with initial efforts in the 1750s to put down the Chin-ch'uan Rebellion..[46]

As a senior colleague of Chuang Ts'un-y.ü, who served as a grand secretary more or less continuously from 1755 until 1773, Liu Lun presented the Chuangs with an ideal opportunity to strengthen the marriage links between the two lineages. Thus, when Chuang Ts'un-yü's second daughter, née Chuang T'ai-kung, married Liu Lun's youngest son, Liu Chao-yang, it represented a unification of the two most important lines within two extremely powerful higher-order lineages in Ch'ang-chou. Their combined influence extended into the upper echelons of the imperial bureaucracy. For all intents and purposes, the Chuangs and the Lius, via Chuang Ts'un-yü and Liu Lun, had engineered a marriage alliance of remarkable social, political, and intellectual proportions. Liu Lun's second son, Liu Yueh-yun, himself a Hanlin

[45] Ch'ing-tai chih-kuan nien-piao , vol. 2, p. 981. See also Chu-chi Cbuang-shih tsung-p'u (1883), 7.36a-37b, and P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), 18b.38a.

[46] See the Chuan-kao of Liu Lun, no. 5741. See also Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1792), 2.38a-40a; (1876), 2.81a-83b. Cf. Ch'ing-tai chih-kuan nien-piao , vol. 1, pp. 138-41, 609-14; vol. 2, pp. 965-68.

academician and grand secretary, would later compose a preface for the 1801 Chuang genealogy..[47]

Counting the Chuangs' twelfth generation and Lius' fourteenth generation as a single one within an affinal framework, we discover, more or less contemporaneously, five Hanlin academicians, four grand secretaries (including assistants), and one grand counselor within this inter-lineage social formation. Chuang Ts'un-y.ü and his younger brother, Chuang P'ei-yin, as secundus (1745) and optimus (1754) respectively on the palace examinations, both served as personal secretaries to the Ch'ien-lung Emperor early in their careers. In overlapping periods, Chuang Ts'un-yü, Liu Lun, and Liu Hsing-wei served in the Grand Council and Grand Secretariat. All three were affinally related.

When we include the clan relations that brought Chuang Yu-kung (see above), a Cantonese and optimus on the 1739 palace examination, into kinship ties with the Chuangs in Ch'ang-chou through the efforts of Chuang Ts'un-yü, the picture of powerful Ch'ang-chou lineages well-positioned in mid-eighteenth-century Peking politics is even more compelling. Chuang Yu-kung had served as assistant grand secretary (1746-47), education commissioner for the Lower Yangtze region (Chiang-nan hsueh-cheng, 1748, 1750-51), and governor of Chiang-su (1751-56, 1758, 1762-65) and Che-chiang (1759-62) provinces.

We have noted above that Yu-kung's appointment in Su-chou as governor of Chiang-su placed Ch'ang-chou (and the Chuangs) under Chuang Yu-kung's jurisdiction. Lineage interests, cemented through clan association with Yu-kung, could be expected to further, legitimately, the Chuang's position in their home province and prefecture while Yu-kung served there. It was hardly any accident, then, that Chuang Ts'un-yü urged Yu-kung to prepare a preface (dated 1761) for the Chuang genealogy, then being revised. The 1760s and 1770s marked the height of Liu and Chuang political power in the Ch'ien-lung era. The Ho-shen era of the 1780s would force them into careful retreat..[48]

The above account situates the reemergence of New Text Confucianism in Ch'ang-chou during the late eighteenth century within the lineage structures and affinal relations we have described. Liu Chao-yang, who

[47] See Freedman, Chinese Lineage, pp. 97-104. See also earlier citations from P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), and Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1792 and 1876).

[48] Ch'ing-tai chih-kuan nien-piao , vol. 1, pp. 138-41,609-14, 624-32; vol. 2, pp. 974-89.

married T'ai-kung (née Chuang), finished first on the special 1784 chü-jen examination administered by the Ch'ien-lung Emperor on the last of his six Grand Canal tours to the Yangtze Delta. The emperor was overjoyed that the son of one of his trusted advisors had done so well. Chuang Fu-tan (see above)—who had married the daughter of Liu Hsing-wei (Chao-yang's immediate uncle)—also passed that examination.

But Liu Chao-yang declined high office and contented himself with the life of a schoolmaster. Compared with his two more distinguished elder brothers—Liu T'u-nan, a 1768 chü-jen, and Liu Yueh-yun, a 1766 chin-shih, Hanlin academician, and grand secretary—Liu Chao-yang led a scholarly life in the company of his talented wife devoted to poetry, the Classics, mathematics, and medicine. As we shall see in chapter 4, Liu's "contentment" may have been enforced. His brothers' careers in the bureaucracy were cemented before the 1780s, which witnessed the rise of Ho-shen and his corrupt followers to prominence. In 1784, therefore, Liu Chao-yang faced an uncertain political career. His influential father-in-law, Chuang Ts'un-yü, was opposed to Ho-shen but was helpless to break Ho-shen's hold over the aging emperor. His powerful father, Liu Lun, had died in 1773. The Lius and Chuangs now had to tread very carefully in the precincts of imperial power. One wrong move and the cumulative efforts of generations of Lius and Chuangs to further the interests of their kin could be undone by an unscrupulous imperial favorite.

Liu Chao-yang's son, Liu Feng-lu, first studied poetry and the Classics under his mother's direction, before continuing his classical education in the Chuang lineage school. Women had considerable influence with their sons, husbands, and fathers, and were therefore important participants in affinal relations between lineages. Liu Feng-lu's mother, for instance, brought her son to her father, Chuang Ts'un-yü, for instruction at an early age.

Under Ts'un-yü's direction, Liu studied the Classics and other ancient texts before turning to Tung Chung-shu's Ch'un-ch'iu fan-lu (The Spring and Autumn Annals' radiant dew) and the Kung-yang Commentary based on Ho Hsiu's annotations. From his maternal grandfather, he absorbed the "esoteric words and great principles" (wei-yen ta-i ) that Chuang Ts'un-yü had stressed in his writings and teachings. Ts'unyü was so pleased with the progress of his precocious grandson that when Liu was still only eleven, Chuang remarked: "this maternal grandson will be the one able to transmit my teachings." The old man,

politically defeated in his last years, had toward the end turned to the New Text Classics to salvage a hope of victory over a corrupt age. His grandson would transmit the message to a post-Ho-shen age..[49]

As Chuang Ts'un-yü's major disciple, Liu Feng-lu, represented the culmination of the development of the Ch'ang-chou school. After Feng-lu, New Text Confucianism transcended its geographical origins to become a strong ideological undercurrent through the writings of Kung Tzu-chen and Wei Yuan. Both of the latter studied in Peking in the 1820s under Liu Feng-lu's direction when Liu was serving in the Ministry of Rites..[50]

In the next chapters, we shall begin to analyze the New Text ideas transmitted by Chuang Ts'un-y.ü and Liu Feng-lu to the Confucian academic world in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Here, we will conclude by observing that both Ts'un-yü and Feng-lu drew on their links to the cultural resources of their lineage organizations and interlineage connections in Ch'ang-chou to learn and transmit the set of classical ideas that later would be labeled as the "Ch'ang-chou New Text school." Liu Feng-lu, accordingly, was a product of Chuang lineage traditions that crossed over to the Liu lineage through the affinal relations that had been built up since the Ming-Ch'ing transition.