The British Film Boom

You spent a lot of time going back and forth to London during the height of the British film boom.

After Strangelove, I started working pretty quickly on an adaptation of [the novel by John Fowles] The Collector [Boston: Little, Brown, 1963].

Did you stay in England for that?

Yeah, although I quit before the shooting began. The two American producers [Stanley Mann and John Kohn] insisted on finding a way to save the girl [at the end of the story]. At the end of John Fowles' novel, the heroine dies of pneumonia after trying to escape in a rainstorm. Changing that didn't even seem like a possibility. It sounded like a stupid idea. I was not comfortable changing the ending, because of my admiration for Fowles' novel. I even wrote a letter to the London Times protesting this change, and it had some effect on the producers, which gave me a bit of satisfaction. Then they said, "We've been thinking about it. Maybe the real message is that art can triumph over an asshole like the collector." After showing his complete nerd-jerk-nowhere-man creepiness, I contrived to have her escape by outwitting the collector through her art [the girl is an art school student] and ultimately to prevail. So I wrote a couple of scenes where Samantha Eggar was working with a papier mâché sculpture in her cell. I set up a pattern whereby Terence Stamp would open the door of this room and look in very cautiously to make sure she wasn't trying to escape, because a couple of times when he opened the door, she tried to dart out. He would say, "I want you to stand where I can see you from the other side of the room." She created this papier mâché likeness in such detail that it deceived him. He would open the door and look across the room and see "her," when she was, in fact, just behind the door. Because the sculpture was so artfully done, he fell for it. The scene was like Hitchcock. Then she locked the door behind her and [locked] him in her former cell. Years later, she would be seen having a picnic on a lovely day. "It's so lovely here in this pastoral sylvan setting; I can understand why you like to come here," her companion would comment. The camera would then pull away to reveal they are having a picnic just a few feet away from the cellar door. By this stage, they had gone too far back toward the original premise for them to use the new ending that I proposed.g

The making of Casino Royale was a fairly acrimonious affair with all the directors from John Huston and Robert Parrish to Joseph McGrath. You spent a fair amount of time as an uncredited writer on the film[*]

* Joseph McGrath, the Scottish director, who worked with Richard Lester on The Running Jumping and Standing Still Film, then directed for television, most notably the BBC series, with Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, Not Only . . . but Also. Casino Royale was to have been McGrath's feature film debut, but the producer Charles Feldman hired, fired, and then rehired him along with four other directors—Robert Parrish, Val Guest, John Huston, and Ken Hughes—and the results were edited together. Other writers, credited and uncredited, included Wolf Mankowitz, Michael Sayers, Joseph Heller, Ben Hecht, and Billy Wilder. McGrath's other film credits include Thirty is a Dangerous Age, Cynthia, and The Bliss of Miss Blossom, and, or course, the adaptation of The Magic Christian. Southern and McGrath later worked on an unproduced film version of William Burroughs' Last Days of Dutch Schultz and a spoof about the Cannes Film Festival.

I received a call from Gareth Wigan, a famous British agent, who was representing me at the time. He had this call from Peter Sellers saying Peter wanted me to write some dialogue for him on this movie. Wigan said, "I think you can ask whatever you want, because the producer, Charles Feldman, wants to make it a blockbuster." There was a lot of heavyweight on that movie because of Orson Welles and Woody Allen. However, Woody Allen and Peter were such enemies on that film that I didn't really associate with anyone but Peter. An extraordinary thing happened. Because Woody Allen was having such a bad time on the picture, his agent came over to the Dorchester Hotel to speak to him one day. When he came into the lobby, he was dead sure he spotted his client Woody Allen at the newsstand reading a paper. The agent came over and said, "Hey, Woody, we're gonna fix that fucking Sellers, and he'll be off this picture." But it was actually Peter Sellers he was talking to. Sellers immediately realized that it was a case of mistaken identity and of course went right along with it, apparently giving a masterful impersonation of Woody Allen. He used to repeat this imitation with the grimace and glasses. The agent kept ranting for three or four minutes how Sellers should be fired and some specific things like "I've seen his contract, and I know how much he's getting, blah, blah, blah," and then he split. Peter was so irate—later he was amused—that he walked straight out the door and flew home to Geneva and announced he was taking a few days holiday. So this multimillion-dollar movie came to an abrupt halt. It was an incredible situation costing thousands a day. They tried to shoot around Peter in his big confrontation scene with Orson Welles in the casino. Welles was furious. They didn't even have all the actors in the master shot, just some stand-ins, and each day, they would shoot around whichever star didn't show up.

There were a lot of writers involved on that project. Can you remember which scenes you wrote?

Just the Peter Sellers stuff. I rewrote all his dialogue in the scenes he was in. I just rewrote with an eye to giving him the best dialogue, so that he would come out [of the film looking] better than the others. I earned an enormous amount for work which I essentially did overnight.

Where would you stay in England when working on a film?

I was staying at the Dorchester during Casino Royale. I stayed at a number of hotels. Writing on a contract for a major studio, you get the very best. I

would go back and forth on these over-the-Pole flights, where you would go from LA to London. I wrote a lot during those flights.

You spent a fair amount of time socializing with the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and others in the scene associated with Robert Fraser's London art gallery.

I knew about Robert Fraser's gallery because friends of mine like [artists] Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, Larry Rivers, and others would show there. Robert Fraser was an extraordinary guy. Kenneth Tynan lived on Mount Street near the gallery. He used to take me to a lot of places like that. Fraser's gallery became very common knowledge in the industry. One day, Tynan said I had to meet this friend of his, Colin Self, who had done this extraordinary piece of sculpture which was like the Strangelove plane. They wanted me to pose with it at Fraser's gallery. That was my first actual trip there. While I was there, Michael Cooper,[*] the photographer who took some pictures, said, "You must come over [to my place] for drinks. Mick and Keith are going to be there." Robert used to have this very active salon at his flat. So I went over and got to know them in a very short time. Christopher Gibbs, the antique dealer and production designer for Performance [1970], was part of the crowd at Robert Fraser's. Then there was Tara Browne, who was killed in the car crash John Lennon wrote about in "A Day in the Life." Sandy Lieberson, who was an agent who optioned Flash and Filigree and produced Performance, was there a fair bit. He was involved with the American film industry in London. I wasn't around during the actual shooting of Performance, but I heard a lot of talk about it from James Fox and his father, [the film and theatrical agent] Robin Fox.

Wasn't your old Paris buddy [the novelist] Mordecai Richler still living in London then?

He was in fact living there and so was [the director] Ted Kotcheff. We had these great poker games.

Did you meet the Beatles around the same time?

I met the Beatles at exactly the same time, because Michael Cooper was doing several of their album covers. He had that market sewed up.

Do you remember how they decided to choose your face for the cover of Sgt. Pepper?[**]

* Michael Cooper died in 1973, but his photographs of the period can be found in two wonderful books, The Early Stones; 1962–1973 (New York: Hyperion, 1992) with text by Terry Southern, and Blinds and Shutters (London: Genesis/Headley, 1990), both edited by his former assistant, Perry Richardson.

** In the upper left-hand corner of the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover, Terry Southern wears big dark glasses, with Tony Curtis on his right, Francis Bacon just off to the left, and Lenny Bruce, Anthony Burgess, and W. C. Fields just above.

I was probably one of the few people they knew who wasn't an icon of a sort. Most of the other faces on the cover were historical choices. [Of all the Beatles] I am closest to Ringo. Ringo was a very good friend of Harry Nilsson. Through Ringo, I met Harry, who I became grand good friends with and later worked [with] on scripts like The Telephone for Hawkeye, a company that we formed.

Candy (1968)

Before Candy was directed by Christian Marquand, you were involved in the adaptation as a coproducer as well as writer.

Yes, the first plan for Candy was for David Picker, who was the head of United Artists at the time, to produce and Frank Perry to direct. Perry had just come off David and Lisa, [1963], so he was big. We were going to get Hayley Mills to play Candy. She was perfect. [However,] John Mills, her father, wouldn't let her do it. We were still in the process of trying to persuade him to let her do it when David Picker lost his position. Then, my good friend Christian Marquand, the French actor who was trying to break into directing

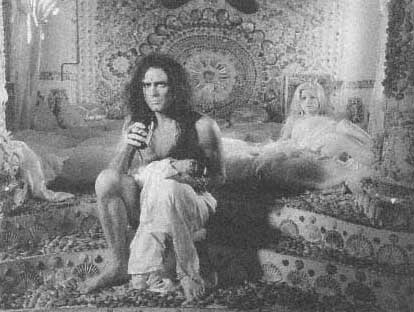

Marlon Brando and Ewa Aulin in the film Candy , based on Terry Southern's novel.

and was certainly competent enough to direct at the time, begged me to let him have the option for two weeks for nothing, so he could put a deal together. So I did, and sure enough, Marquand immediately put Brando in the cast because Brando was his best friend. They were lifelong friends to the extent that Brando named his first son after Marquand. So on the basis of getting Brando, he was able to add Richard Burton and having gotten those two, he was able to get everyone else. Then, he disappointed me by casting a Swedish girl [Ewa Aulin] for the lead role, which was uniquely American and midwestern. He thought this would make Candy's appeal more universal. That's when I withdrew from the film. The film version of Candy is proof positive of everything rotten you ever heard about major studio production. They are absolutely compelled to botch everything original to the extent that it is no longer even vaguely recognizable.

Buck Henry wrote the final screen adaptation. Did you know him at all?

I didn't know him at all at the time. I wasn't even aware that he had written a script of Catch-22. I just thought he was the creator of Get Smart.

Did you look down on TV writers at the time?

Well, how would you feel? I mean, situation comedy! What could possibly be creatively lower than that? It has nothing to do with TV versus film. It's just that situation comedy is mass produced and not something that has much to do with writing.

Barbarella (1968) and Easy Rider (1969)

In the fall of 1968, you went to Rome to work on Barbarella.

Yes, I stayed there during the shoot at Cinecitta. I was living at the top of the Spanish Steps in a good hotel there. It was a good experience working with Roger Vadim and Jane Fonda. The strain was with Dino De Laurentiis, who produced the picture. He was just this flamboyant businessman. His idea of good cinema was to give money back on the cost of the picture before even going into production. He doesn't even make any pretense about the quality or the aesthetic.

Vadim wasn't particularly interested in the script, but he was a lot of fun, with a discerning eye for the erotic, grotesque, and the absurd. And Jane Fonda was super in all regards. The movie has developed a curious cult following, and I am constantly getting requests to appear at screenings at some very obscure weirdo place like Wenk, Texas, or a suburb of Staten Island. Around 1990, I got a call from De Laurentiis. He was looking for a way to do a sequel. "On the cheap" was how he expressed it, "but with plenty action and plenty sex! " Then, he went on with these immortal words: "Of course, Janie is too old now to be sexy but maybe her daughter." But nothing, perhaps fortunately, came of it.

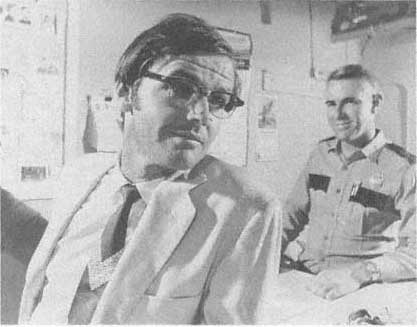

Jack Nicholson in the jail scene in Easy Rider , directed by Dennis Hopper.

Wasn't it during the making of Barbarella that you first began working on Easy Rider?

Yes. Very early on it was called "Mardi Gras" to identify it. The first notion was that it would entail barnstorming cars, stunt-driver cars, which do flips and things—a troupe who play a few dates and places, and eventually get fed up with that, so they make this score—but that just seemed too unnecessarily complicated. So we just settled for the straight score of dope, selling it, and leaving the rat race. We forgot about the commonplace thing of daredevil drivers. Finally, we forewent any pretense of them doing anything else other than buying cocaine. We didn't specify that it was cocaine, but that's what it was. They go to New Orleans to sell it. Then, once they got their money, they ride to coastal Florida or some place like Key West where they could buy a boat cheap—not in New Orleans, because it would be too expensive. That was basically the story, which I then started to flesh out after our initial script meetings.

Did they actually do some kind of formal writing, or was it mainly in the form of tossing around ideas at story conferences?

Story conferences, mainly.

So, when you worked with Hopper and Fonda at your office and during the New Orleans shoot, you would just talk the story out and then go off and physically write the pages?

I did all the writing on it. They just had the idea in the beginning of the two guys making a score and using the money to buy their freedom from the rat race of America. Their pilgrimage on the road. That was all they had. No dialogue.

So you were the only one doing the actual, physical writing on it?

I did the only writing on it. Peter Fonda was the only working actor in the group. Dennis wasn't really into acting at this time. He was a photographer. He had acted a long time before and had been a child actor. He was in Sons of Katie Elder [1965]. Peter Fonda had been in several of these really low-ball series of biker movies for AIP [American International Pictures]. He had a contract for one more in a three-picture contract. Dennis had this idea they would do instead of doing one of their typical B-picture dumbbell movies: under the guise of doing a biker movie, they could maybe pull off a movie that might be more interesting, [and] Dennis would be able to make his debut as a director in one fell swoop. It seemed possible under these auspices, whereas he couldn't get arrested ordinarily. Under the setup where Peter Fonda owed AIP this picture, it would be possible to get this different approach in under the wire. He persuaded Peter to go along with this, "We'll get Terry to write the script!" I had this good reputation off of Dr. Strangelove and Candy.

How did Easy Rider end up at Columbia?

That was through this guy [the producer] Bert Schneider, who made a deal for the distribution rights. He wasn't involved during the production. He made some kind of deal with Dennis and Peter. Peter was the nominal producer. So that was the situation when they came by my place in New York. They said, "We want you to write this, and we're going to defer any money in exchange for splitting 10 percent three ways." For a variety of complicated business reasons, I wasn't in a position where I could defer; so they said, "You can get $350 a week for ten weeks in lieu of that." So I did it that way. So I never had a piece of the film, which turned out to be very lucrative.

Anyway, they told me the basic notion of two guys who were fed up with the rat race and commercialization of America. So, in order to get out of it, they're going to make this score and then head to Galveston or Key West, and buy a boat and take off. The story would involve a cross-country trip and the various adventures that could befall them. The idea of meeting a kind of a straight guy, which turned out to be the Jack Nicholson role, was totally up to me. I thought of this Faulkner character, Gavin Stevens, who was the lawyer in this small town. He had been a Rhodes scholar at Oxford and studied at Heidelberg, and had come back to this little town to do whatever he could there. So I sort of automatically gave the George Hanson character a sympathetic aura. I wrote the part for Rip Torn, who I thought would be ideal for it. When

shooting began, we went to New Orleans and Rip was going to come, but he couldn't get out of his stage commitment in a Jimmy Baldwin play, Blues for Mr. Charlie. At the time, it seemed like there was a possibility he might. We could shoot his part in a few days, and he would still be able to make this theatrical commitment. It wasn't a big part. [The Baldwin play] was a Greenwich Village production and very little bread for him. He was doing it because he felt committed to it. Because he's very much that kind of guy. So he missed the role of a lifetime. And Jack Nicholson was just on the scene, always around. He was a good choice, because he had that sympathetic quality.

How did you feel after the release of Easy Rider, when in interviews Dennis and Peter kind of downplayed the fact that you had written the screenplay. It seemed almost like an attack of amnesia on their part.

Well, vicious greed is the only explanation. And desperation for some ego identity material, because neither one had much of that. Whereas for me, I was filled with an abundance of praise and things.

You said you wanted to talk more about Easy Rider because of a possible lawsuit regarding your rights to it.

I don't want Dennis to do [Easy Rider II ] without notifying me or anything, because in order to get their names [Hopper's and Fonda's] on Easy Rider I had to call the Writers Guild to say it was okay. For a director and a producer to be named on the writing credits is practically unheard of. Since there has been so much coercion, bribery, and so on by directors in the past, tacking themselves onto the credits, nowadays it's an automatic arbitration. And so, I received this phone call from Peter saying, "Well, we've got this print. I think we've got a nice little picture here. Dennis and I want to get our names on the writing credits, but in order to do that, you'll have to notify the Writers Guild to say that it's all right."

Did you think it was a fair request at the time?

It wasn't fair, but it didn't matter to me at the time because I was ultrasecure. I had Candy and Dr. Strangelove. I said, "Sure, that's fine." I didn't mind. So I spoke to the Writers Guild. They were a little surprised. They said, "Well, those guys aren't even members of the Writers Guild. They're not really writers, are they?" I said, "Yes, that's true, but you don't have to be in the Writers Guild to write something," although you are supposed to be in order to participate [in the profits, residuals, et al.].

A lot of people still seem to think Easy Rider was this completely improvised film, but looking at the shooting script, I was surprised to find even the graveyard hallucination scene was completely scripted out. Why did Peter and Dennis take the lion's share of the credit on that film?

Yeah, neither of them is a writer. It's often the case with directors that they don't like to share credit, which was the case with Stanley. He would prefer just "A Film by Stanley Kubrick," including music and everything. Aside from Kubrick, other directors I worked with rarely did anything on the script.

End of the Road (1970)

The director of End of the Road, Aram Avakian, and you were co-conspirators and friends since meeting in Paris in the late forties?

He had a kind of Renaissance-man quality so he just got interested in films.

He edited Jazz on a Summer's Day [1959 ].[*]Was that his first gig?

Yeah, he started work as an apprentice for Bert Stern, who was the director. Aram was invited to direct a film called Ten North Frederick Street [based on the John O'Hara novel]. Ten North Frederick Street was going to be his big chance. Something went wrong there. Then he met some producer who was powerful enough to get him another directing job. The movie the guy got him was called Lad: A Dog, in which the hero was a dog. You can imagine what a challenge that would be. Avakian did some work on the script. He used to come by and discuss things. It reached the state where at the end of the movie, the dog, Lad, was getting married. The story called for a kind of wedding between the dog, this Lassie-type collie, and some sort of very pampered dog of the same breed. Of course, Aram insisted that it shouldn't happen like that, and instead Lad should run off with a mongrel dog. Aram said if he could get away with that, the film would work. What happened was he got fired because the studio wouldn't go along with that.

End of the Road came about through a mutual friend, Max Raab, who was a very nice guy, whose line of business was women's clothing shops, a certain kind of casual wear. Very expensive, very high fashion. Raab wanted to get into show business, and he was very knowledgeable about movies. He said, "Look, you guys find a property, and I'll get hold of about $300,000."

I had just read this John Barth novel [End of the Road (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1958)]. Aram had read it on my recommendation. We simultaneously agreed that it was a good story, and that it would make a good movie. So we got an option on it, wrote a treatment, and showed it to Max Raab—who hated to be called Max A. Raab, being very Jewish. (Laughs. ) So he agreed. We got the money together and hired Steve Kestern, who had worked with Arthur Penn, as our production manager.

Dennis McGuire has a cowriting credit along with you and Avakian. What was his role?

He was some guy who, unbeknownst to us at the time, had an option on the Barth novel. We couldn't buy him out, so we had to cut him in on the writing fee.

Since he wasn't active in the writing of the shooting script, was crediting him a conciliatory gesture on your part?

* A documentary of the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival.

Yeah. In the late summer of 1968, we scouted locations around East Canaan in Connecticut and Great Barrington, Massachusetts. We found this fantastic old button factory in Great Barrington, which was perfect as a soundstage. That's how End of the Road got started. Oh yes, one of the interesting things was that we needed a good director of photography. We couldn't afford a regular one, so Aram had this idea of scanning commercials and getting a director of commercials who wanted to break into features. We started to look at these reels of guys who made commercials, and we noticed one who was much better than the others. We hired the director, who turned out to be the great Gordon Willis.

You were also fortunate to cast people like James Earl Jones, Stacy Keach, Harris Yulin, and Dorothy Tristan. The film has some very interesting effects and a startling opening montage.

We tried to give the film a full-on sixties flavor—student unrest and so on—which seemed inherent in the book. A very good book, and, I like to believe, a most faithful adaptation, with a little something extra in the form of Doctor D's [played by James Earl Jones] theories.

The Magic Christian (1970)

Your next big project was The Magic Christian. That project had been in gestation for about four or five years before shooting started in February of 1969.

The way it evolved was that Peter Sellers and Joe McGrath had been working together with Richard Lester on his Running Jumping and Standing Still Film [1960], so they got to be good friends. McGrath had been working as an assistant to Richard Lester. McGrath wanted to direct something on his own. He asked Peter what would be a good movie to direct. And that turned out to be The Magic Christian. Peter had bought a hundred copies of my novel to give out on birthdays and Christmas. Joe McGrath thought it was a match made in heaven, so Peter immediately started to develop the property. Peter had a contract with some studio which had produced his last movie. He told them Christian was going to be his next movie and he wanted Joe to direct. Did they want to finance it, or did they want him to look somewhere else? Their first reaction was "Yes, we'll do it!"

Was it your idea to give Guy Grand a son, which, along with switching the location from America to England, was the major departure from the novel?

Well, that came about because the producers wanted to get what they called some extra box-office appeal. Peter had seen me hanging out with Paul [McCartney], I think, and said, "Well, Terry knows the Beatles. Maybe we can get one of them." Ringo had said that he would like to be in the movie. So I said, "How about getting Ringo?" I've forgotten who came up with the specific

On the set of The Magic Christian : Terry Southern and a certain Richard Starkey, O. B. E.,

a pop star of some note.

idea of having one of the Beatles as Guy Grand's son, Youngman Grand, but I was willing to try it.

I understand you completed the script with Joseph McGrath, but that he and Sellers and company made changes while you were busy with End of the Road.

When I finally made it to the set of The Magic Christian, I spent a lot of time doing damage control. It was probably due to Seller's insecurity or a manifestation of that. Although he loved the original script and it was the key to getting started, he also had this habit where he would run into someone socially, like John Cleese or Spike Milligan, and they would get to talking, and he would say, "Hey, listen, can you help me on this script?" They would come in and make various changes, sometimes completely out of character from my point of view. I found these scenes, a couple of which had already been shot, to be the antithesis of what Guy Grand would do. They were tasteless scenes. Guy Grand never hurt anyone. He just deflated some monstrous egos and pretensions, but he would never slash a Rembrandt—a scene which they had in the movie. There's a scene at this auction house, where, just to outrage the crowd or the art lover, Guy Grand and his adopted son bribe the auctioneer to deface this great painting. Guy Grand would never do that. It was gratuitous destruction; wanton, irresponsible bullshit which had nothing to do with the character or the statement. It was very annoying. They shot the auction scene and agreed to take it out for a time, but it stayed in the final cut. Peter did come around to seeing it was tasteless.

There was no dissenting opinion on the film.

No, Joe McGrath didn't dissent. He could have dissented at the time they were making these changes, because he was the director. He had a more disciplined sense of comedy than Peter, if not Peter's flaring strokes of genius. McGrath didn't have that much control, and he was so in awe of Peter that he wasn't able to resist him.

Towards the end of production, you shot the final scene with Guy Grand and his son persuading various passersby to wade into a tank full of manure and help themselves to money floating at the top of the mess [—the tank was] at the base of the Statue of Liberty.

Peter insisted we had to shoot that scene under the [real] Statue of Liberty. The producers resisted because of the expense of the trip. They were ready to shoot it there in England. So Peter, in a fit of pique and rage, said, "Well, I'll pay for it!" and then they said, "No, we'll pay for it!" We were going to fly first-class to New York and shoot the scene. Then Gail [Gail Gerber, Southern's companion since the midsixties], of all people, noticed this ad saying the QE2 [Queen Elizabeth II ] was making its maiden voyage. She said, "Wouldn't it be fun to go on the QE2 instead of flying?" Peter thought that was a great idea. He assumed that it wouldn't be any more expensive than flying first class, but it turned out to be much, much more expensive. Flying was like

$2,500 a person; but going in a stateroom on the QE2 was $10,000 a person, because there were all these great staterooms on the QE2. The dining room was beyond first-class. Like, really fantastic. Instead of eating in the ordinary first-class place, [we] had this special dining room. It was called the Empire Room. It was a small dining room with about six tables in it. That was another $2,000 right there. But the producers were committed to it.

Before we left, I'd introduced Peter to this Arabic pusher, who had given Peter some hash oil. Peter put drops of it on tobacco with an eyedropper, and smoked the tobacco; or if he had cannabis, he would drop the oil on that and smoke it. It was just dynamite. Like opium. Peter became absolutely enthralled. He couldn't get enough of it. It was very strong stuff. So we all went on this fantastic five-day crossing. The whole trip was spent in a kind of dream state.

So there was you, Peter, Gail, and Ringo?

Yeah, Ringo, his entourage, his wife, and some of the kids. We never saw the kids. They were usually with the nanny. There was also Dennis O'Dell, the producer, and his wife.

That trip must have cost, as Guy Grand would say, "a pretty penny."

Yeah, I saw the figures on it once. The crossing cost about twice as much as the shot. They didn't use the shot of the Statue of Liberty in the end.

In 1969 and 1970, you had three major films in release with your name attached to them. Was it a good situation to have that kind of momentum, or was that a complicated time because of controversies like End of the Road's X-rating?

Yeah, that [X-rating] didn't seem to help. Easy Rider did get a nomination, like Strangelove. It also won the Writers Guild Award [in its category] for that year. You would think you would have more leverage in a situation like that. I am sure that you are sensitive enough to imagine how not having certain projects get off the ground could feel. If there were anything to be gained from indulging that feeling, I would certainly pursue it. It just seems like a silly thing to think about, because it's self-defeating.