An Introduction to Meaning

In this chapter, because of the interrelated complexities of the Devi cycle, we will interrupt its description from time to time for essays or remarks on its meaning as introduced or most clearly demonstrated by particular aspects of the cycle. We may start with some comments on these accounts of the introduction of the Nine Durgas into Bhaktapur.

These stories or legends relate the Nine Durgas to a particular period of time and to specific events in the history of Bhaktapur and to particular places in Bhaktapur's space. This quasi-historicity contrasts with the locally and historically transcendent Puranic[*] mythlike stories of Devi as Mahisasuramardini, which, while also contributing secondarily to the troupe's meaning, are central to Mohani. The themes in the legend are repeated and modulated throughout the Devi cycle. We may well begin with the now familiar distinction of outside and inside. This is in its major emphasis a distinction between outside and inside the city itself with the ritual boundaries of the city being understood as the significant border—thus the Nine Durgas are captured outside of the city and brought into it. But once inside they are still "outside" the city in a sense, for they are in the Acaju's or Brahman's inner secret room, and still separated from the public space of the city. That inner room is in

this sense outside of the house (where wife and family are), as the house itself (with its own secrets guarded from its surrounding neighborhood) is outside of the public space of the city itself. The Nine Durgas move from forest to secret room to the house and then, finally, to the public urban space of Bhaktapur. Both the outside of the city beyond its ritual boundaries and the nested, successively more private realms inside a household or inside a corporate group, are in different ways "outside" the city as a public realm.

The Nine Durgas live outside the city in a forest. They have many of the characteristics of predatory beasts which are reflected in the iconic details of their masks. Like such beasts, they are dangerous in that they kill and eat people. it is essential to note that they kill people not because of their "sins" or violations of the dharma , but simply because of accidental encounters. Sunanda Acaju simply chanced upon them. The Nine Durgas are threats to the bodies of those who happen to encounter them. They are not related to people's souls , to their moral behavior, and the manipulation of karma as are the ordinary gods of the inside of the city. In fact, as we have noted in our discussion of sacrifice, the death of the body in such encounters because it represents a sacrifice to a deity results—as does an animal sacrifice for that animal—in a great reward to the soul, phrased sometimes as mukti or moksa[*] , that is, salvation. The Nine Durgas, like all dangerous deities, are brought under control not through ordinary moral action nor the kind of devotion that influences ordinary deities but by an act of power, the Tantric mantra of a particularly skillful practitioner. Ordinary people, as we will see, can control them only through blood sacrifice.

In the legends, the Tantric control of the wild divinities of the outside is first used for the private and secret enjoyment of the Tantrikas. The action is still outside the city in the sense that it is hidden from the public realm and of no consequence to it. This private pleasure is disrupted through the prying of a wife who is pejoratively characterized as curious and small-minded and who in one version is even punished by death. Her violation of her husband's authority, of his injunction "do not look in this room," caused the escape of the dangerous forces and her immediate punishment. Through the wife's meddling an essential transformation takes place, however—the powerful amoral gods move from the private personal realm of the Tantric Brahman to the public space of the city for the use and good of the city as a whole.[4] This legendary transformation reflects the way that Bhaktapur has turned Tantra into a Brahmanically controlled or at least supervised civic reli-

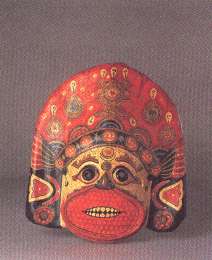

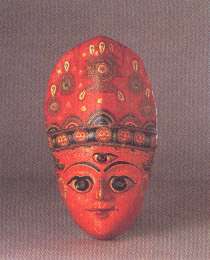

Mahakali H. 46 cm., W. 38 cm.

Bhairava H. 46 cm., W. 38 cm.

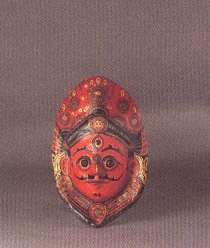

Kumari H. 42 cm., W. 24 cm.

Sero Bhairava H. 22 cm.,W. 27 cm.

Siva H. 33 cm., W. 22 cm.

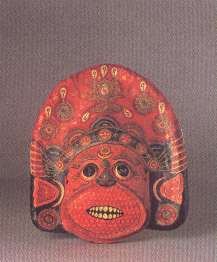

Sima H. 40 cm., W. 34 cm.

Duma H. 40 cm., W. 34 cm.

Varahi H.40 cm.,W. 34 cm.

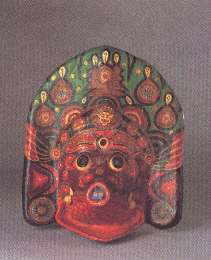

Ganesa[*] H. 43 cm., W. 36 cm.

Mahesvari H. 42 cm., W. 24 cm.

Indrani[*] H. 42 cm., W.24 cm.

Vaisnavi[*] H. 42 cm., W. 24 cm.

Brahmani H. 42 cm., W.24 cm.

gion, although a religion that continues to represent the exterior forces which surround, threaten, and sustain the interior moral and civic life of the city.

There is another story told to explain why the Nine Durgas ate the pig. This second story illuminates an important aspect of meaning of the Tantric gods in general and the Nine Durgas in particular—that is that the Tantric and dangerous deities represent a power that transcends purity and impurity. This power can absorb and neutralize problematic quantities and placements of impurity and thus help to maintain and restore that segment of social order that is differentiated by purity and which is the concern of the ordinary gods who partake of the ordering dependent on purity.

The story goes that in a past age the people of the earth had been polluting the earth with urination and defecation. Everywhere the world was dirty and everywhere there were bad smells. The gods consulted with Visnu[*] and asked him, as he had so often done, to come to the help of the world. The gods did not want to do anything to get rid of the feces themselves for fear of contaminating themselves. Finally Visnu[*] agreed to incarnate himself as a pig and to eat the feces. "But," he said to the gods, "if I do this I will become polluted, and it will be difficult for me to again escape from the world." The Nine Durgas said to him that they would agree to take and eat the pig as a sacrifice, and thus through the sacrifice of that pig make it possible for it (and the incarnate Visnu[*] ) to gain salvation.