Chapter Five

Emotional Health and Cancer Survival

No one can ignore the possibility that emotional factors may affect survival among the ill. Philosophers and theologians through the ages have counseled against distinguishing too sharply between mind and body. The question of whether emotions affect cancer survival lies outside the usual concerns of modern biology and medicine. But the realization that neither technical breakthroughs nor preventive measures will soon eliminate cancer as a major cause of mortality underscores the importance of new alternatives. The remainder of this book will concentrate on factors that involve thinking, behavior, and conditions of life. Despite the achievements of biomedical science in cancer, these factors may, for many individuals in the century to come, make the real difference between life and death.

Scientists encounter major difficulties when they attempt to assess the impacts of emotions, behavior, and social and economic conditions on cancer survival. Psychologists, sociologists, and economists work with information that is considerably "softer" than that of the more traditional sciences. Engineers have developed instruments capable of very accurately assessing clinical facts such as the concentration of blood gases and enzymes. But social scientists must usually ask people questions in order to obtain data on their personal habits, states of mind, family incomes, and cultural beliefs. The uniqueness of each human being makes it hazardous to compare one person's response with that of another. Individual human beings interpret questions differently and, in their answers, may express the same thought in different words. Unlike a

laboratory autoanalyzer, moreover, a human subject responding to a questionnaire may at any time elect to lie.

Health professionals and social commentators with interests in the relationship between emotions and cancer have labored against these difficulties. Many have bypassed the cautious methods upon which scientists have traditionally insisted. Collections of anecdotes have been widely used in attempts to demonstrate connections between cancer survival and personality, outlook, and mood. Otherwise, proponents of the emotional theory have looked to the traditional sciences, citing principles and studies that appear to support their belief in a link between emotions and survival. Some scientific studies have focused directly on the relationships of emotional factors to cancer survival. But only a few have been carried out under rules of observation, measurement, and analysis comparable in rigor to those of clinical trials. People who believe in a relationship between psychological factors and cancer survival have never based their position primarily on such studies.

The Seattle Longitudinal Assessment of Cancer Survival (SLACS) serves as an important resource in improving understanding of the role that emotions—as well as other aspects of thinking, behavior, and conditions of life—may actually play in determining who survives cancer. As detailed in Appendix A, the SLACS is a long-term study of survival of people diagnosed with one of four common cancers: malignancies of the lung, pancreas, prostate, and uterine cervix. The SLACS followed 536 people, a large number in comparison with most studies of psychosocial aspects of cancer. The study obtained vast amounts of data on the lives, resources, and problems of these individuals, most elicited through extensively validated, quantitative scales, designed to minimize subjectivity. The SLACS included a battery of detailed questions to detect psychological distress. The resulting accumulation of information has provided an opportunity to study the relationship of psychosocial factors—particularly the emotional states of patients—to cancer survival more comprehensively and rigorously than ever before.

Documentation of a strong relationship between emotional factors and cancer survival would have important implications for treatment. Just as some believe that preventive efforts should replace the current emphasis on finding a cancer cure, others contend that spiritual and psychological interventions may be more effective than traditional medicine at curing cancer. In view of their powerful implications, emotional theories of cancer survival require objective assessment.

Two types of inquiry provide a basis for assessing the strength of the

theory linking emotions and cancer survival. The first is a review of the cultural underpinnings of the theory. Rather than science, deep-seated beliefs among American and some European thinkers have given rise to this popular approach to explaining cancer mortality. The second is a close examination of actual scientific studies of emotional factors and survival, with special attention to the studies that most closely approximate the rigor of traditional clinical trials.

The Emotional Theory of Survival

Many popular writers today tell their audiences that psychological factors predispose people to contracting cancer and that improved emotional health enables cancer patients to recover. The field of behavioral medicine, which looks to psychological techniques for solutions to organic health problems, is in the forefront of this thinking. Michael A. Lerner, a leading exponent of this perspective, makes a firm connection between the cancer patient's emotions and his or her chances for recovery. Discussing the benefits of group therapy sessions for cancer patients, he writes: "You become different from the person who developed the cancer. Becoming different personally may change the environment the cancer grew in; it may become so inhospitable that the cancer shrinks."[1]

Quoted in D. Goldman, "The Mind over the Body," New York Times Magazine, September 27, 1987, p. 39.

This kind of thinking finds considerable sympathy in the American public. Every family, in fact, seems to have its own anecdote. A grandfather, mother, sibling was diagnosed with cancer. Doctors called the condition hopeless and sadly informed the family that the patient had less than a year to live. But the relative outlived the doctors' predictions, by six months, a whole year, several years. The survivor had an extraordinary "will to live," the family often explains. The doctors could not appreciate this "fighting spirit." A kind of mystical gift helped the individual triumph over dread disease. Indeed, the family might add, this spirit, outlook, or gift appeared in many aspects of the person's life and relations with others. The relative's ability to "beat" cancer was just one more manifestation of his or her basic personal capabilities, talents, and blessings.

Professional and popular support for a psychological explanation of cancer survival reflects the strong tradition of individualism in America. Generally, Americans seek the causes of individual success and misfortune

within the individual. The tradition of individualism extends to the worlds of academic achievement, work, family stability—and, increasingly, to health. The millions of joggers, dieters, and voluntary psychiatric clients in America today attest to this tradition's persistence. The appeal of prevention as an approach to cancer owes at least part of its strength to this individualism. Like fitness and self-care, prevention offers people a means of avoiding the disease by taking action on their own behalf.

Few if any would dispute the importance of individual attitudes toward disease, feelings about oneself, or willingess to take steps to ameliorate or overcome personal misfortune. Few, moreover, would exclude from the realm of legitimate medicine techniques designed to reduce the cancer patient's level of anxiety or depression. A good family physician should pay sufficient attention to both the observable lesion and the patient's perceived comfort. But those seeking to understand the factors that increase or reduce cancer survival must question psychologically based theories, despite their appeal to basic American values. It is essential to examine the cultural heritage on which this approach is based, and the scientific studies to which its proponents have looked for support.

Culture and the Psychology of Survival

Speculation about relationships between the mind and cancer predates modern medicine and extends beyond the ranks of American individualists and orthodox medical practitioners. A number of classical medical sages, including Galen, believed that sadness, depression, and "melancholia" led to cancer. Women were thought to be especially susceptible to contracting cancer for emotional reasons. While these sages contributed much to the development of modern medicine, it is also important to remember that they had no knowledge of germ theory or biochemistry and treated their patients with mineral baths and bloodletting.

In modern times, German psychologist Wilhelm Reich did much to publicize the notion that psychological factors cause cancer, linking the disease with sexual repression. Although intermittently popular in the United States, Reich was eventually jailed for fraudulent promotion of a device to enhance sexual capacity. Reich died, discredited and destitute,

in a mental hospital. His influence has periodically resurfaced, however, and his name appears now and then in popular psychology.

Practitioners in better standing than Reich have helped disseminate the notion that mental condition can contribute to the risk of cancer or affect the cancer patient's chances for survival. In the 1970s, a series of works by physicians and psychologists linked cancer incidence and survival with lassitude and isolation during childhood,[2]

C. Thomas, ed., The Precursors Study: A Prospective Study of a Cohort of Medical Students, vol. 5 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983).

self-pity and an inability to retain close relationships,[3]O. C. Simonton, S. Matthews-Simonton, and J. L. Creighton, Getting Well Again (New York: Bantam, 1978).

and apathy, self-contempt, and the feeling that life holds no more hope.[4]L. Le Shan, You Can Fight for Life: Emotional Factors in the Causation of Cancer (New York: M. Evans, 1977).

But the principal source of popular belief in a relationship between state of mind and cancer has almost certainly been culture rather than science. In the late 1970s, critic and essayist Susan Sontag reviewed a broad range of cultural elements that link emotions with physical disease.[5]

S. Sontag, Illness as Metaphor (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1978).

At the most basic level, these elements include the language of everyday discussion in which people describe and conceptualize illness. They also occur in "high culture," as themes running through novels and poetry that associate depression, pessimism, and a negative outlook on life with fatal disease.Sontag's essay focuses primarily on two diseases, tuberculosis and cancer. Culture has tended to transform both diseases, tuberculosis in the nineteenth century and cancer in the twentieth, from objective clinical entities into emotionally charged cultural themes. In their respective eras, science could not adequately explain these diseases and medicine could not cure them. They came to be perceived as insidious, mysterious, and hopeless. These supposed qualities made them attractive to commentators and writers as metaphors for describing people and social phenomena. Persons who contracted these diseases were, in turn, believed to possess the secretive and hopeless qualities that the diseases represented in literature.

Writers of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries associated peculiarly positive qualities with the secretiveness and hopelessness attributed to tuberculosis. The literary genre took tuberculosis to be an expression of frustrated passion. Writers in this tradition most often traced such frustration to unfulfilled love. Keats, for example, attributed his "consumption" to separation from his mistress. Tuberculosis could be caused not only by thwarted love but also—particularly among the creatively inspired—by poverty. Mimi in La Bohème exemplifies this etiology. Both varieties of frustration appeared to involve self-renunciation by the high-minded. In this respect, tuberculosis was perceived as a "noble" form of illness. The nineteenth-century metaphor presented

tuberculosis, a disease identified with the chest and upper body, as an affliction of the soul.

Tuberculosis, according to Sontag, lost its appeal as a literary fantasy with the development of definitive treatment in the twentieth century, and was replaced by cancer as a metaphor in language and literature. Metaphorically, cancer shares the secretiveness, insidiousness, and hopelessness once attributed to tuberculosis. In this metaphor, cancer is also associated with spiritual deprivation. But instead of a noble frustration of acknowledged passion, cancer is viewed as stemming from denial of passion, suppression of anger, stifling of creativity, repression (into the Freudian "unconscious") of desire, and personal defeat. In contemporary discourse, one hears of cancer as an "invasion," people who contract cancer as "victims," efforts to develop cures as "crusades." Political discussion has adopted cancer as a metaphor to describe evil imposed from without. It is a small logical step to explaining the individual's developing or succumbing to cancer as an absence of "life force," an unwillingness or spiritual inability to fight the invader.

Sontag's analysis suggests that the mysteries, fantasies, and personal attributes encompassed by the cancer metaphor make no more sense than the obsolete metaphor surrounding tuberculosis. She writes: "As once TB was thought to come from too much passion, afflicting the reckless and sensual, today many people believe that cancer is a disease of insufficient passion, afflicting those who are sexually repressed, inhibited, unspontaneous, incapable of expressing anger. These seemingly opposite diagnoses are actually not so different versions of the same view (and deserve, in my opinion, the same amount of credence)."[6]

Ibid., p. 21.

Sontag implies that the need for disease metaphors to express our fears about personal insufficiency, social change, and political instability will outlast the serviceability of cancer for that purpose. In the mean-time, she suggests, the belief that personality flaws cause cancer or reduce survival chances amounts to a distasteful exercise in "blaming the victim."

What Sontag views as a mere fantasy destined to be abandoned with the development of improved cancer treatment, however, has achieved perhaps unprecedented popularity through the work of a literary figure of comparable stature. Norman Cousins's recollection of his personal experience with illness became a best-selling critique of medicine in the 1980s.[7]

N. Cousins, Anatomy of an Illness as Perceived by the Patient (New York: Norton, 1979).

Cousins was hospitalized for a progressive, debilitating illness that his physicians were unable to diagnose. He soon became frustrated with his care and surroundings, turned to literature recommending "thefull exercise of the affirmative emotions as a factor in enhancing body chemistry," and accordingly changed his environment and treatment regimen. In a now well-known search for recovery, Cousins left the hospital and moved to a nearby hotel. The move both improved the comfort of his surroundings and reduced the cost of his care. But most important, Cousins claims to have developed a program to trigger "affirmative emotions" through laughter, with the aid of comic literature and Groucho Marx films. Cousins apparently recovered, concluding that "the will to live is not a theoretical abstraction but a physiologic reality with therapeutic characteristics."[8]

Ibid., p. 44.

Cousins himself did not agree with the conclusion that he "laughed" his way out of a crippling disease that doctors thought was irreversible. But his report is widely interpreted in that way. Several "experimental" programs, in fact, have been initiated to apply the principles "established" by Cousins's experience, most often focusing on patients hospitalized with advanced malignancies.

A prolific writer and longtime editor of the Saturday Review of Literature, Cousins had cultural rather than scientific credentials. He based his comments largely on personal experience—reporting, for example, a newfound ability to sleep after viewing a Groucho Marx movie. Although he cited scientific studies, he did not claim to be scientific and did not make specific recommendations for treatment. In the late twentieth century, however, clinicians began to offer emotionally based treatment regimens on the basis of evidence no more substantial than that cited in Cousins's writings.

Psychotherapy for Cancer

Cousins's description of his illness points out serious shortcomings in modern medical care. He had no scientific proof that he actually "cured himself with laughter." But he raised important issues about the priorities of medicine in the late twentieth century. The technical capabilities of medicine in this era often far outran concerns for the patient's comfort and dignity.

Influential writers and practitioners have developed methods of therapy consistent with this thinking. Dr. O. Carl Simonton is the most famous of these practitioners. Simonton states his view of the importance of emotions in cancer as follows:

It is our central premise that an illness is not purely a physical problem but rather a problem of the whole person, that it includes not only body but mind and emotions. We believe that emotional and mental states play a significant role both in susceptibility to disease, including cancer, and in recovery from all disease. We believe that cancer is often an indication of problems elsewhere in an individual's life, problems aggravated or compounded by a series of stresses six to eighteen months prior to the onset of cancer. The cancer patient has typically responded to these problems and stresses with a deep sense of hopelessness, or "giving up." This emotional response, we believe, in turn triggers a set of physiological responses that suppress the body's natural defenses and make it susceptible to producing abnormal cells.[9]

Simonton, Matthews-Simonton, and Creighton, Getting Well Again, p. 10.

Simonton and his colleagues have applied this perspective in a well-known therapeutic program. At their Fort Worth Center, they conduct a program designed to stimulate the psychological processes believed to promote recovery from cancer. The program utilizes several "mental imagery techniques," which aim to strengthen patients' belief in their treatment, their body's natural defenses, and their ability to solve the problems they had before becoming ill. Simonton and his followers believe that creating alternative imaging will improve chances for recovery by increasing immune activity and decreasing abnormal cell production.

Individuals may carry out the six-week Simonton program on their own or through many hospitals. It begins with a prescription for reading books that explain the "interrelatedness of mind, body, and emotions." The program continues with exercises to overcome stress and resentment, promote commitment to recovery, explore feelings about death, and set goals for the future. Explicit imagery is apparently quite important. Among their successful patients, the Simonton team presents individuals who thought of their radiation treatments as volleys of bullets and their white blood corpuscles as sharks eating cancer cells.

Simonton and his colleagues use mostly anecdotal evidence to support the merits of their treatment method. They describe patients with the proper attitudes who experienced complete remissions from cancer or lived "many months beyond" their prognoses. They cite the familiar "placebo effect" as indirect support. They describe, for example, a man who received the experimental drug Krebiozen in the 1950s. The patient, they report, made steady progress until he learned that research studies had proven the drug ineffective. Only positive beliefs, they conclude, could have explained the patient's improvement followed by decline.

Simonton, Cousins, and other popular writers who explain cancer

survival in terms of positive emotions do make reference to "research studies" in their books and speeches. Usually, though, these references are brief and lack detail about the conduct of the research or possible problems in its interpretation. People reading or listening for inspiration or entertainment may find these vague obeisances to the authority of science reassuring. But those who are seriously concerned with identifying who survives cancer and what may be done to increase an individual's chances must go considerably further.

Determining the real value of the emotional theory of cancer—and, just as important, its potential applicability in cancer therapy—requires detailed examination of scientific studies. Like lawyers arguing a case, commentators on health and medical care often select only those studies from the vast scientific literature that support the positions they favor. A practitioner with a particular point of view may convince an unwary reader on the basis of research reports that are fundamentally flawed. People who have a serious need to obtain accurate information on what genuinely works in cancer treatment must assess the strength of research cited to support a particular therapeutic approach, and weigh these studies against those that may support an opposing opinion.

What Do the Studies Really Say?

Proponents of the emotional theory of cancer survival have tended to draw selectively on studies done in the 1960s and 1970s by scientists in many fields. Some of these studies are well designed and executed, but others are scientifically very weak. Some of the investigations have focused directly on human survival; others, on organisms or life forms quite distant from human beings. Of the studies that appear generally acceptable to the scientific community, some seem to support the psychological theory of survival, others contradict the theory, and still others have proven inconclusive.

Laboratory Research

Cousins, Simonton, and others of their persuasion regularly allude to laboratory research to support their assertions. This type of research engenders respect because it sounds like real science. It takes place in a setting presumably equipped with the traditional scientific

trappings—glassware, chemical reagents, electronic measurement devices. Researchers perform experiments that expose tissues to factors thought to produce or inhibit cancer, and perform tests utilizing objective measurements and standard statistical techniques to see whether the stimuli had the expected results.

Laboratory scientists have, of course, performed many experiments to test theories that changes in body chemistry can cause or control cancer. Studies of this kind have concentrated, first, on the immune system. It is believed that a healthy immune system can identify and destroy cancer cells, which, like bacteria or viruses, are foreign bodies. Scientists have also focused their attention on hormones. Distributed through the bloodstream to tissues all over the body, these substances coordinate the actions of a variety of organs and affect cancer cells in important ways. As discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, established treatment methods include hormone manipulation for several cancers, and hormones are suspected as causes of some forms of the disease. Mainstream cancer research has focused strongly on the immune system in the search for new treatments.

Some experiments have addressed the possibility that emotions affect the immune system, and thus the ability of the body to fight cancer. This theory is especially important because some scientists think the body regularly produces a small number of cancer cells. If the immune system spots the abnormal cell and deals with it effectively, no tumor develops. Visible disease occurs only when the immune system breaks down. Advocates of this theory have reasoned that emotional stress causes cancer by interfering with the immune system.

An experiment by two laboratory investigators in the late 1960s illustrates the type of study often cited as evidence that emotions affect the immune system.[10]

W. G. Glenn and R. E. Becker, "Individual v. Group Housing in Mice: Immunological Response to Time-Phased Injections," Physiological Zoology 42 (1969): 411-16.

These investigators injected bovine serum albumin (BSA) into mice bred specifically for experimental purposes. It was known that each mouse's immune system would recognize this substance as foreign and would produce antibodies to destroy it. The experimenters wished to identify factors that affected the mouse immune system's response to the substance. One factor was the housing conditions under which the mice were kept. Some shared their cages with five other mice; others were kept alone.After several weeks, the scientists tested blood samples from the mice for evidence of immune response. They reported that the mice kept in isolation had weaker immune responses than those kept in cages with other mice. They concluded that the psychological consequences of

isolation accounted for the differences. These findings, they commented, "demonstrate for the first time that injection of a foreign protein in mice involves an immunological response that can be affected by the psychophysiological experience accompanying separation from other mice."[11]

Ibid., p. 414.

Hormones constitute the second major subject of laboratory-based research on relationships between emotions and cancer. The theory linking human feelings and behavior with cancer via the intervention of hormones is compelling. Everyone knows that anxiety, fear, and anticipation of certain stimuli cause changes in pulse rate, blood pressure, and glandular secretions. This is the basis for the polygraph lie detector, which records physiological changes in response to stress produced by untruthful testimony. Actual or anticipated misfortune or happiness apparently stimulates nervous reactions, which in turn activate the hypothalamus and pituitary glands. These kingpins in the body's biochemistry cause several other glands to secrete hormones—most notably, steroids by the adrenals. In essence, this is a description of the familiar "fight-or-flight" response that all animals have to threats in their environment.

Furthermore, scientists have demonstrated important connections between hormones and cancer. Some female cancers—such as endometrial and uterine malignancies—can develop only in the presence of stimulation by estrogen, a female sex hormone. Likewise, scientists have linked breast cancer with high concentrations of estrogens. In men, prostate cancers are dependent on the androgens, or male sex hormones. Prostate cancer never develops in their absence. Scientists have identified a wide variety of additional hormones—many of which are secreted in response to emotional stimulation—as growth factors in these and other cancers.[12]

M. E. Lippman, "Psychosocial Factors and the Hormonal Regulation of Tumor Growth," in Behavior and Cancer, ed. S. Levy (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1985), pp. 134-47.

But scientists investigating the relationship between emotions and resistance to disease have not always come to the same conclusions. Some research findings suggest that conditions associated with emotional disturbance may actually increase an animal's resistance to a wide range of illnesses, including cancer. While some researchers report that mice housed alone have a weaker immunological response than mice housed in groups, others find that solitary mice develop greater resistance to certain parasitic diseases than mice housed with other mice.[13]

M. Stein, R. C. Schiavi, and M. Camerino, "Influence of Brain and Behavior on the Immune System," Science 191 (1976): 435-40.

Some studies report that mice who fight with other mice have greater resistance to disease than tranquil members of their species. But other experiments indicate that fighting mice develop decreased resistance to illness. Likewise, basic science research on immune factors and hormoneshas major inconsistencies. The body's immune system fights disease, and an increase in its capabilities protects the individual from cancer—or so it would seem. But the authors of one study remark, "It is now believed that the development and course of only some tumors are restricted by immune activity and that immune factors may actually stimulate tumor growth under certain conditions."[14]

S. J. Schleifer, S. E. Keller, and M. Stein, "Central Nervous System Mechanisms and Immunity: Implications for Tumor Response," in Behavior and Cancer, pp. 120-33, at p. 122.

Increased hormone secretions—particularly those produced by the cortex areas of the adrenal glands—are associated with the growth of cancer. But research also documents beneficial effects from the presence of such hormones. Some of these agents are extensively used in cancer therapy. Patients whose tumor cells have molecular configurations capable of binding to these hormones have increased chances of responding positively to therapy.[15]

M. E. Lippman, "Clinical Implications of Glucocorticoid Receptors in Human Leukemia," Cancer Research 38 (1978): 4251-56.

Clinicians who look to behavioral and emotional factors to help patients survive cancer try to back up their claims with laboratory experiments reported in the scientific journals. In fact, these experiments leave undecided the question of whether—and, perhaps even more important, how—emotions affect cancer. On the biochemical level, the relationships between cancer survival and immune factors and hormones are very complicated. Intense research in these areas continues. Impacts of immune factors and hormones differ from disease to disease. The final answer may never be known. Experiments focusing on emotional stimuli and behavior, moreover, do not give clear messages applicable to humans. How do crowded housing conditions and fighting behavior among mice translate into emotions experienced by people? Do humans fare better emotionally in cramped city apartments or roomy suburban homes? Should we consider isolation stressful, as it may be to shipwrecked sailors, or serenely pacifying, as it seems to religious hermits? Does fighting behavior stated in human terms signify anger and hostility or a healthful release of pent-up feelings?

Laboratory studies cannot answer the question of whether emotional well-being helps people survive cancer. In attempts to add stress to the environments of mice, monkeys, and other small mammals, biomedical experimenters have resorted to a variety of mechanisms, including crowding, food deprivation, and electric shocks. These conditions may change the animals' body chemistries. But to what, if any, human emotions do these animal reactions correspond? The chemical and nervous responses in animals may affect their resistance to bacteria or parasites to which the scientists expose them. But there are immense differences between these simple responses and the highly complex

immunology of cancer. Studies in the laboratory have thus far failed to move the connection between emotional distress and cancer survival beyond anecdotes and theories. Real progress requires that scientists observe people with cancer, assess their emotional states, and monitor their survival.

Human Survival Studies

Scientists have in fact done human studies, employing different techniques from the experiments just described. Unlike laboratory animals, people will seldom let experimenters subject them to noxious stimuli. Scientists do not usually expose human subjects to disease, and certainly not to cancer. Instead, studies of human beings almost always focus on patients already diagnosed with cancer. Researchers perform psychological tests on cancer patients and use the test results to predict the patient's survival time. Hospitals and specialized cancer treatment centers serve as research sites. Already having undergone much testing and many medical procedures, these patients often make willing (or at least complaint) study participants. Medical records that are regularly updated tell the investigators how long each patient lives after his or her diagnosis.

These studies almost always employ standardized tests developed by psychologists and psychiatrists to indicate emotional well-being or distress. The tests usually include series of questions asking the subject whether he or she feels hopeless, sad, blue, suspicious, withdrawn, happy, or satisfied. Other types of questions may request subjects to select preferences—"going out to see friends" versus "staying home and watching television," for example. They may ask the individual to describe some aspect of his or her behavior or social surroundings and resources. Responses to the questions are grouped into indices. Each index is designed to reflect a psychological characteristic, such as tension, depression, anger, resignation, or isolation. Psychiatrists have developed indices to measure syndromes such as neuroticism and paranoia. One large-scale test—known as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, or MMPI—has been given to countless college students, military recruits, and job applicants over several generations to assess fitness for special tasks and identify emotional problems.

It is difficult to believe that questions as simple as the ones appearing on these forms can measure complex human attributes. But they have several highly useful qualities. Because they are standardized, they allow

for objective evaluation of individual moods and personalities. Being human themselves, clinicians may allow personal prejudices and "gut feeling" to influence their evaluations of certain patients. The indices themselves are validated by determining whether people with mood disturbance, neuroticism, etc., assessed according to alternative means, receive high scores on these indices.

The 1970s gave rise to a series of widely reported studies linking emotional characteristics with survival among cancer patients. A highly influential study assessed characteristics of women with breast cancer, including anxiety, hostility, depression, guilt, and "psychoticism."[16]

L. R. Derogatis, M. D. Abeloff, and N. Melisartos, "Psychological Coping and Survival Time in Metastatic Breast Cancer," Journal of the American Medical Association 242 (1979): 1504-8.

A standard psychological test, the SCL-90-R, was used. The investigators reported that certain psychological characteristics were associated with long-term survival. But the report contained some major surprises. While Cousins, Simonton, and others in the behavioral medicine movement connected affirmative emotions with cancer survival, this study connected survival with what must be termed negative emotions. The report indicated that the long-term survivors had higher levels of anxiety, hostility, and psychoticism than the short-term survivors. They also had poorer attitudes and more hostility toward their physicians.A study of patients with malignant melanoma, a highly aggressive form of skin cancer, produced similar results.[17]

G. N. Rogentine et al., "Psychological Factors in the Prognosis of Malignant Melanoma: A Prospective Study," Psychosomatic Medicine 41 (1979): 647-55.

This study used a "melanoma adjustment scale" to predict relapse after surgery. On this scale, patients were asked to rate from 1 to 100 the amount of personal adjustment needed to cope with their life-threatening disease. If a great deal of personal adjustment had been required, the subject indicated a high number on the scale. The study found that the higher the score on the melanoma adjustment scale, the less likely the individual would be to experience a relapse. Again, fundamentally negative rather than positive emotions seem to correlate with a better prognosis in cancer. People who feel they are undergoing substantial personal adjustment appear likely to encounter more stress, depression, and disruption of lifestyle than those able to take their disease in stride.The authors of both the breast cancer and the melanoma studies make an effort to interpret their results in a manner consistent with the tenets of behavioral medicine. According to the authors of the breast cancer study, the higher levels of anxiety and hostility really reflect a "fighting spirit," which may explain the tendency to survive. The authors of the melanoma study say that a higher "adjustment rating" may indicate greater willingness to acknowledge and confront the disease. In a rhetorical manipulation of major proportions, anxiety, hostility, and a difficult

process of adjustment are thus transformed into positive emotions capable of increasing the patient's chances for survival. It seems far more likely, however, that these findings actually reflect neither firm nor especially meaningful research results. In both studies, the number of patients followed is extremely small (thirty-five in the breast cancer study and sixty-seven in the melanoma study), raising the possibility that the findings may be entirely accidental. Both studies followed patients for only one year. In all, neither the breast cancer nor the melanoma study collected enough data.

The breast cancer study has several other difficulties. The "long-term" survivors (those who survived for one year) were on the average six years younger than the ones who lived less than a year. Longer-term survival could have been traced simply to the age differences. All things being equal, younger people will always outlive their elders. Younger people, moreover, are more likely to criticize and make demands on their physicians. Finally, people who are healthier, and thus less likely to die soon, appear more likely to have the strength and motivation required to express tension and exhibit hostility—to their doctors or anyone else.

Few other studies remedy these shortcomings. An English researcher and his colleagues followed breast cancer patients for up to ten years.[18]

S. Greer, T. Morris, and K. W. Pettigale, "Psychological Response to Breast Cancer: Effects on Outcome," Lancet 2 (1979): 785-87.

His psychological tests led him to conclude that "optimistic attitudes" predicted survival. In his study, patients who looked upon their breast surgery as inconsequential or merely precautionary tended to survive longer. However, this study followed only fifty-seven patients. In addition, it leaves open the question that underlying disease may affect the patient's responses to the psychological tests. A breast cancer patient with more serious disease is less likely to interpret her illness or treatment as minor, and also is less likely to survive long-term.The pronouncements of several distinguished and widely read authors exemplify a strong popular belief in America today—namely, that positive emotions increase an individual's chances of surviving cancer. Both literary figures and physicians subscribing to this belief often refer to research to support their contentions. The examples presented above typify the research these proponents cite in their writings. But none of the studies examined here provides convincing arguments that emotional well-being improves cancer survival. Laboratory studies almost always focus on tissues extracted from animals or on levels of blood components, such as hormones. Their findings are extremely remote from human beings with or without cancer and are difficult to apply to

human survival. Though more directly applicable, most of the widely cited studies of humans are too small in scope, too short in length, and insufficiently definite in their measurement of psychological factors to provide much truly valuable information on the relationship between emotional health and cancer survival.

Debunking the Myth: New Research Findings

Despite the weakness of pertinent research, many people still believe that patients who are emotionally distressed are more likely to die from cancer than those who are emotionally healthy. Patients, health professionals, and managers of health care delivery clearly require more definitive studies than most of those reported so far. Only improved studies can give patients accurate expectations, provide health professionals with good indications of the effectiveness of newly proposed treatments, and guide managers of health plans and medical practices in their selection of appropriate benefits for the seriously ill.

The best study of emotional factors in cancer survival would take the form of a clinical trial, akin to experiments that are standard in traditional biomedical research. In such a study, patients would be randomly assigned to different treatments—some, perhaps, to the Simonton method; others, to a traditional mode of treatment or a placebo situation, i.e., one known to be therapeutically neutral. As late as 1990, no such studies had been done.

Because scientists are reluctant to place people in randomized studies of unconventional treatment methods, clinical trials of emotionally based interventions may never take place. But investigations approximating the rigor of a clinical trial may provide better information than those usually cited in support of the emotional theory of survival. Studies of this kind must include several definite methods and procedures absent in the work reported earlier in this chapter.

First, these studies would have to be prospective. In prospective studies, researchers observe in advance the factors they expect to influence recovery or survival time. Such studies contrast with retrospective investigations, in which researchers locate survivors and attempt to assess their emotional well-being, or merely ask the survivors to explain their good fortune. Prospective studies require investigators to follow

large numbers of patients over time. Many can be expected to die during the study. Prospective studies, however, lend themselves best to systematic comparison of survivors and nonsurvivors.

Next, the survivors and nonsurvivors compared in these studies must be similar in all respects other than the factors on which the researcher desires to focus—in this case, psychological health. In the event that an apparent relationship is found between emotional health and survival, the researcher must be able to rule out the possibility that other factors actually explain the result. For example, an apparent relationship between depression and poor survival chances may be explained by the plausible argument that patients with more advanced disease tend to experience more depression.

Third, a rigorous piece of research must use standardized measures of psychological factors. These include the extensive observational or paper-and-pencil tests familiar to most psychologists, such as the MMPI or SCL-90-R. These standard indicators keep investigators from consciously or unconsciously attributing to individual patients characteristics consistent with the favored hypothesis.

Fourth, a study with the required rigor must observe a fairly large number of patients. Studies of fewer than several hundred patients may fail to detect important relationships. Even where a relationship does exist between a measure of psychological well-being and survival, for example, a smaller number of observations may not support statistical significance. It is important to remember that statistical significance means that an observed relationship is unlikely to have occurred by chance.

Finally, a rigorous study must include clear hypotheses that specify the expected relationship between variables of interest. In the present context, these variables would include psychological factors such as stress, depression, inability to express oneself, lack of social adjustment, and other difficulties. These factors would be used to predict an outcome such as recovery from disease or extended survival time. The classical scientific tradition holds that researchers must be able to test hypotheses by systematically observing facts.

A Rigorous Investigation Of Psychology And Survival

Rigorous studies of the relationship between psychological well-being and cancer survival are just beginning to appear in scientific

journals. One such study, nearly unique in its inclusion of the required features, was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1985.[19]

B. R. Cassileth et al., "Psychosocial Correlates of Survival in Advanced Malignant Disease?" New England Journal of Medicine 312 (1985): 1551-55.

Many physicians and scientists consider this journal the world's leading publication in biomedical research and medicine. In this study, University of Pennsylvania professor Barrie R. Cassileth and several of her colleagues observed 204 patients with cancers that were too advanced or rapidly spreading to warrant an attempt at surgery. They tested a series of hypotheses linking psychosocial factors and longevity. These researchers used thirty-two questions to measure various dimensions of psychological well-being or disturbance, including strength of social ties and marital history, job satisfaction, use of psychotropic drugs, general satisfaction with life, subjective view of health, helplessness and lack of hope, and perceived difficulty in adjusting to a diagnosis of life-threatening disease. All questions used were drawn from earlier studies by established researchers, and thus represented standard means of measuring psychological distress.The Cassileth study was prospective. Patients were recruited for study during stays at the University of Pennsylvania hospital and were interviewed shortly after diagnosis of cancer. In many important respects, the patients were quite similar. Eligibility for the study included a strict and narrow set of disease characteristics, precluding the mixture of likely survivors and persons facing near-term mortality. Clinical factors such as site of the cancer, extent of the disease, and treatment received, moreover, were not statistically related to the psychological variables. The absence of such a relationship strongly suggests that patients with "good" versus "bad" psychological test outcomes differed only on the psychological variables themselves. Patients were followed until they died or for up to five years after their diagnoses.

This landmark study found no relationship between emotional well-being and survival. None of the relationships between the psychological variables tested and survival was statistically significant. Only familiar biological variables, such as extent of disease and limitations on physical functioning (probably related to the organic disease process), predicted early death.

Individual studies are never definitive. Cassileth herself recognizes that psychological factors may play a more important role in the survival of persons with more favorable prognoses. Most of the patients in her study were essentially incurable. Critics carped at the measures used by Cassileth, arguing that larger numbers of questions must be used to assess each individual psychological dimension. Noting the limitations

of the measures used in the Cassileth study, one group of critics comments: "In their belief that psychosocial factors can be adequately represented by seven poor measures, the authors ignore the dynamic richness and variety of human experience."[20]

P. P. Vitaliano, P. A. Lipscomb, and J. E. Carr, Letter to the Editor, New England Journal of Medicine 313 (1985): 1355.

The conviction that psychological well-being improves survival chances is difficult to shake. Believers in the theory of course question the Cassileth findings. The research issues are indeed complex and require additional, confirmatory studies with the same rigor as Cassileth's study, using alternative means of psychological measurement. The SLACS provided an opportunity for such an investigation.

Emotions And Cancer Survival: The Slacs Findings

The SLACS provides an unusually detailed look at cancer patients. Based on a survey of 536 individuals, it encompasses a larger number of cases than most psychosocial investigations. Through extensive face-to-face interviews, the researchers were able to obtain vast amounts of reliable data on the lives, problems, and psychosocial well-being or distress of these patients. The resulting accumulation of data enabled the investigators to perform a study of psychological factors in survival that was more rigorous than perhaps any conducted in the past. Moreover, they were able to follow individual patients for up to eighty months, reinterviewing many on several occasions to monitor important changes in life conditions and outlook. All patients were followed for at least five years.

The SLACS included a long series of questions designed to measure psychological well-being. One particularly useful set of measures was the Profile of Mood States, or POMS. The POMS uses sixty-five individual questions to measure a series of variables similar to those examined by Cassileth: tension, depression, anger, confusion, fatigue, and vigor. Groups of individual questions are combined to generate indices of these variables, a process substantially reducing measurement error. Specialists in measurement of psychological variables have repeatedly examined the POMS for reliability and validity, confirming that persons taking the POMS respond the same way in repeated administrations and that the individual indices—tension, depression, etc.—measure the characteristics their names suggest. The POMS is particularly useful since it has been employed in several studies of cancer patients.

To assess the impacts of psychological well-being versus distress on

survival, the SLACS investigators used each of the POMS scales as independent variables. They focused on two dependent variables reflecting mortality risk. First, they examined five-year survival. For statistical comparison, researchers often consider cancer patients who survive five years after diagnosis to be "cured." Second, they assessed the relative mortality risk of people with differing scores on each of the POMS measures—that is, the ratio of mortality risk (over the entire course of the study) among patients with higher-level POMS scores versus mortality risk among patients with lower-level POMS scores. While less familiar than five-year survival, relative risk is sometimes more important. This variable is more closely related to the length of time patients may be expected to live after diagnosis. Among persons with aggressive forms of cancer, methods of extending life for limited periods of time may be more important than attempts at cure as traditionally defined.

The researchers used statistical procedures that took account of important characteristics, other than emotional states, that may also have affected an individual patient's survival chances. These variables included age, sex, and the key disease features, cancer site and stage. Details of this analysis appear in Appendix B.

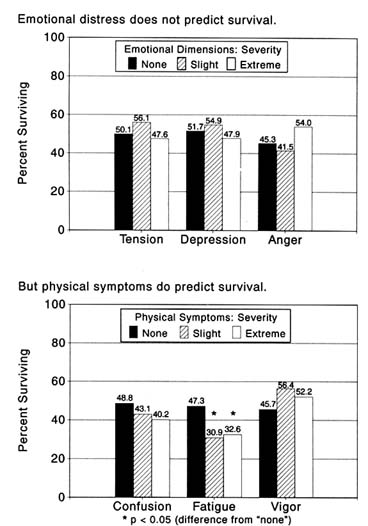

Figure 5 summarizes the results of this analysis, comparing five-year survival among individuals with differing score ranges on individual dimensions of the POMS. Persons with low numerical scores on an individual POMS dimension (e.g., "Tension") are considered free of noticeable symptoms or pathology on that dimension; in Figure 5, their symptom level is designated as "none." The symptoms of persons with middle-range scores are characterized as "slight"; those of persons with high scores are characterized as "extreme." To evaluate the possibility that differences presented in Figure 5 were observed by mere chance, levels of statistical significance were computed. In computing statistical significance, the researchers compared percentages of five-year survivors in the "none" category with percentages of five-year survivors in the "slight" and "extreme" categories.

The percentages appearing in Figure 5 are not direct observations. They are adjusted for differences in survival that may be traced to factors other than scores on the POMS—factors such as the patient's sex, age, and cancer site or stage. Computations for this chapter combine cancers of the lung, pancreas, prostate, and cervix.

Figure 5 presents no evidence that an individual's level of tension, depression, or anger makes a life-or-death difference. None of the relationships of anger, tension, or depression to five-year survival is large

Fig. 5. Emotional distress, physical symptoms, and five-year survival rates.

enough to rule out the likelihood that it was observed by chance. Percentages of five-year survivors in the categories designating "slight" and "extreme" symptoms, moreover, are sometimes higher than in the category labeled "none." The pattern—or, rather, the absence of a pattern—linking these POMS dimensions with relative mortality risk is highly similar.

Figure 5 presents a more consistent set of findings based on the POMS dimensions of confusion, fatigue, and vigor. In comparison with individuals who show no discernible levels of confusion or fatigue, those with slight or extreme levels have poorer chances of five-year survival. Less vigorous people have lower chances of five-year survival. The figures include statistically significant differences on the dimension of fatigue. Statistics computed for relative mortality risk follow a highly similar pattern.

Some may view these findings as support for the position that psychological well-being indeed promotes cancer survival. But a closer look at the measures casts doubt on such a conclusion. Although the six dimensions measured by the POMS are intended to reflect "mood states," only half of them really indicate emotional phenomena. Tension, depression, and anger are clearly emotional dimensions. Strong arguments can be made, however, that confusion, fatigue, and vigor actually reflect physical phenomena. These three terms do not sound truly psychological. Research has demonstrated, moreover, that indices with the latter three titles in the POMS correlate strongly with other disease symptoms and physical dysfunction among the seriously ill.[21]

H. P. Greenwald, "The Specificity of Quality-of-Life Measures among the Seriously Ill," Medical Care 25 (1987): 642-51.

It appears essential to view the POMS Tension, Depression, and Anger indices as measuring perhaps related but different phenomena from the Confusion, Fatigue, and Vigor indicators.When viewed with this distinction in mind, Figure 5 provides no indication that emotional distress affects cancer survival. The relationships that do appear in Figure 5 are easily explained as the consequence of physical disease. Cancer patients who report that they are extraordinarily tired (indicated by "fatigue" and "vigor") are likely to be sicker, and hence more likely to die in the near term, than those who are physically less ill. The confused patient could well be taking pain-killing or mood-altering drugs.

Other measures in the SLACS also cast doubt on the psychological theory. Two indices from the widely used Sickness Impact Profile (SIP)[22]

M. Bergner et al., "The Sickness Impact Profile: Conceptual Formulation and Methodological Development of a Health Status Index," International Journal of Health Service 6 (1976): 393-415.

showed no relationship with either five-year survival or relative mortality risk. One index, built from nine separate questions, measured "emotionalbehavior," a composite of such adverse feelings as self-blame and hopelessness. The other index, comprising twenty separate questions, measured impaired social interaction resulting from illness; individual questions touched on loss of humor, withdrawal of affection, self-isolation, and the like. Many health researchers consider marriage a reflection of emotional stability and a cause of positive adjustment and feelings. Married people observed in this study, however, had no survival advantage, beyond what might have been observed by chance, over those who were not married.

Finally, the SLACS detected no evidence that the patient's mood state deteriorates with the approach of death. Patients with the most aggressive forms of cancer (lung and pancreatic) were interviewed every two to three months, and this process was repeated as many times as possible before the patients became too ill or died. Among these patients, average levels of tension, depression, and anger tended to remain constant over the successive interviews. The consistency of these observations has two implications. First, it suggests that a single measure of mood state soon after diagnosis is a good reflection of the patient's general feelings over time. A specialist in measurement might conclude that the POMS reflects not just emotional "state" but long-term "trait." Second, the view over time confirms the impression from Figure 5 that psychological distress does not, in general, foreshadow death.

Implications Of Slacs Findings

For professionals and patients concerned with obtaining an accurate, objective assessment of the relationship between emotions and cancer survival, the Cassileth study and the SLACS represent crucial sources of information. Because these studies observe large numbers of patients and follow each individual prospectively to monitor his or her survival, they differ markedly from the investigations usually cited by supporters of the emotional theory of survival. Perhaps along among studies of emotional factors and cancer survival, these two investigations used objective, quantitative measures of psychological variables. Both studies share the important feature of separating possible effects of disease and personal-background factors from the effects of psychological state. Clearly, the Cassileth study and the SLACS come closer to the rigors of traditional science than most other investigations of the psychosocial aspects of cancer. Neither of these two powerful studies provides evidence that the patient's emotional state affects his or her chances for survival in any way.

Devotees of the emotional theory of cancer survival often cite Hans Selye as the founder of their approach. He was one of the most important of the modern physicians who have studied the relationship between stress and illness, publishing studies in this area as far back as 1936. Authors of influential books on the relation of emotions and behavior to heart disease draw upon Selye's contributions; writers on Type A and Type B behavior, for instance, usually refer to Selye's pioneering work. Simonton, Cousins, and other popular authors look to Selye for evidence on the relation between emotional well-being and cancer survival.

Selye, however, was extremely cautious about explaining cancer on the basis of emotions and behavior. Reviewing a vast quantity of research findings shortly before his own death, Selye pointed out that, while stress produced some hormonal responses that might produce cancer growth, stress could produce responses that inhibited such growth as well. Summarizing the research, he concluded that "a certain predisposition is necessary in all … maladies, and the same is true of cancer, in which the role of stress has been extensively studied, but is still far from clear."[23]

H. Selye, "Stress, Cancer, and the Mind," in Cancer, Stress, and Death, 2nd ed., ed. S. B. Day (New York: Plenum, 1984), pp. 11-19, at p. 12.

Selye was even more cautious about the benefits of psychiatric and behavioral interventions intended to prolong the lives of cancer patients. He wrote:

Considerable literature has accumulated concerning the relationship between cancer and the mind. The interpretation of most of the reports is extremely difficult and subject to doubt. It has even been claimed that, under certain conditions, neoplasms can result from psychosomatic reactions in that certain predisposing personality characteristics and emotional states may play a significant role in the development, site, and course of cancer. On the other hand, regression of malignancies as a consequence of the patient's strong will to survive has also been postulated, but there is little tangible evidence to support such a view. Perhaps the most pressing task in this connection is to develop a code of behavior among patients with incurable malignancies and to train medical personnel in the techniques of making these trying times as tolerable as possible to the patients and to their relatives.[24]

Ibid., pp. 15-16.

Anecdotes cited as evidence for a connection between emotions and cancer survival, moreover, might be very different if the lives of their subjects were followed for any length of time. It would be useful to monitor the lives of patients of Simonton and others in the therapeutic movement he represents. How long do the enthusiastic, positive-sounding patients receiving this form of care actually survive? How typical is the fate of a SLACS patient who died soon after giving this enthusiastic testimony: "I went to the doctor to ask about pain under my ribs. I was

given X rays, waited two days for the results, and then was rushed to emergency surgery. I couldn't breathe. The doctor said it was a malignant tumor. Everyone prayed—and at the surgery, they never found it. The Lord had removed the tumor—there was no trace."

In the late twentieth century, two approaches to the cancer problem outside the realm of orthodox medicine became quite popular. The first asserted that preventive measures could solve most of the cancer problem. The second alleged that favorable emotions and attitudes could reduce cancer mortality. Both approaches appealed to the basic American value that people can attain the most difficult goals by adopting the proper attitudes and taking action on their own behalf. Both could well have reflected frustration with the slow rate of progress medicine seemed to be making in pursuit of a cure for cancer. Both appear to stem from cultural support for individual initiative, exaggeration of fundamentally sound theory and facts, and perhaps wishful thinking.

As late as the 1990s, the few rigorous investigations of the relation between psychological factors and cancer survival indicated no potential benefit from interventions addressing the patient's emotional state. Researchers, practitioners, and policymakers should continue to seek ways outside the strictly technical offerings of medicine to increase cancer survival. A better understanding of the part played by human thinking, behavior, and conditions of life may indeed suggest important new steps to be taken. But the most promising approaches to reducing cancer mortality outside the traditional thinking of biology and medicine appear likely to involve areas other than the individual patient's attitude, personality, or mood.