2—

Saving Babies for France

15—

Royal Brevet: "Sent by the King":

Versailles, 19 October 1759

France is still in the midst of the devastating series of battles eventually to be known as the Seven Years War, and the government is obsessed, as always in a military crisis, with how badly it needs soldiers. But this time the problem is felt acutely. Whereas the War of the Austrian Succession had ended in something of a stalemate with England in 1748, now France is losing its possessions and influence throughout the world. The king's troops are dying in Canada, India, Minorca, Hanover, Westphalia, Senegal, the Mississippi basin, the Caribbean. Mutilated, crippled veterans, the pathetic survivors who return, are an increasingly common sight. The war, an utter rout, is pushing up both debt and taxes, pushing down morale. It is a catastrophe.

Since the Regency, the nation has been alarmed about what it perceives as a rapidly plummeting population. Montesquieu's Persian Letters in 1721 had dealt at some length with this matter. Many reasons have been suggested for the decline: the celibacy of Catholic priests, the "fanaticism" that forced Protestants to flee after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, slavery in the colonies, the waste of lives in war, the debauches of luxury, the fact that most domestics in the cities do not marry, the neglect of agriculture, the impossibility of divorce and re-pairing.[1] But high on the list is infant mortality, the flagrant waste of human life at its very start. This, it is agreed, must be stopped. Women's bodies have as a result gradually come to be thought of as a kind of national property, somehow coming under the stewardship and use rights of the state, counted on to ensure the regular fecundity of society. Married women are considered morally obliged, patriotically bound to perform the public function of producing citizens. The fertility patterns and reproductive capacity of the country poor in particular are under close surveillance. Children are now discussed almost as commodities, building blocks of the state's prosperity, their safekeeping a central economic concern. Raulin's De la conservation des enfants is one of several best-sellers on the subject. The death of babies is viewed more and more as a public crime, a form of lèse-majesté.[2]

Today, in this connection, the king officially launches the midwife's nationwide teaching mission. He issues his Brevet en faveur de la Demoiselle Boursier du Coudray sage-femme , a special reward for her fine practice of midwifery, her machine, the great success of her work in Auvergne, all of which make her richly deserving of His Majesty's protection. But he has much more than mere thanks in mind. He now desires that her zeal, her talent, her knowledge, be "liberally distributed" throughout France, under royal patronage and protection. She is to travel freely wherever she judges appropriate, "without encountering, for any reason, trouble from any person or under any pretext whatsoever." Intendants, commissaires départis , officers, justiciers and all other administrators must see to the execution of this brevet. The king signs, to show this is his will and it must be obeyed.[3]

For nearly a decade the royal ministers have heard reports of the midwife's uncommon gifts, and since the outbreak of hostilities with England in 1756 they and Frère Côme and the intendant of Auvergne seem almost to have been readying her for this national task. Le Boursier du Coudray has cooperated fully. Her work teaching huge numbers of midwives in the Clermont region, already legendary, fits right into this pronatalist program. The king knows of her dedication, loyalty, and special talents. And he makes what turns out to be a smart bet on her ambition and herculean energy. Is it any wonder that he would select her to enlighten all of France and press her into service for the crown?

The royal brevet is both less and more than the midwife expected. Although she has hoped for years to be promised some ongoing monetary pension, the king still does not give her that regular salary. But the brevet is a veritable consecration of her work, turning her skill into a national institution. It recognizes officially the moral and political value of what she is doing, safeguarding her and her students, at least in principle, against the kinds of problems they have just encountered in Plauzat. Not that one can legislate emotions. But the spirit of the brevet is to clear the way for this mission and to signal and warn anyone who would openly, flagrantly, thwart it. A grand destiny has just been sanctioned for the midwife "demoiselle" by the monarch himself. And she will not let anyone forget it.

It is worth pausing on this, because the men with whom the

midwife deals, unaccustomed to receiving directives from a woman, will naturally have mixed feelings about her. They admit her skills, some graciously, some grudgingly, but all want to be sure that she doesn't somehow escape from their control, that she remain linked to them or beholden to them in some permanent way. An autonomous woman is unthinkable in this period, a massive threat to the corporate structure, and their willingness to accept and cooperate with her at all comes from their confidence that they can rein her in when necessary, can maintain mastery. This preoccupation is seen at every turn. Even Frère Côme needs to boast that it is he who superintends and manages her travels.

Examples of attempts to circumscribe her abound. The Abrégé itself was held up until a former teacher of hers, Verdier, could attach to it his thirty-five-page "Observations sur des cas singuliers." The first censor of the original manuscript, Morand, had been supportive but with qualifications, saying of the book only, "I think it very useful to midwives of the countryside incapable of more extensive instruction."[4] With the additions by Verdier—the "Observations" refer to seventeen famous obstetrical authorities and cite many books, scholarly journals, and proceedings of learned academies—the second censor, Süe, a master surgeon and accoucheur himself, can say not only that the work is useful to provincial and city midwives, but that it has been raised to a loftier plane.[5] In fact, between the time of Süe's approval and the actual pressing, the male editor had decided to bind the "Observations" in the front of the volume. The midwife has been encouraged by men to write her book, but they want to have the last (or in this case, first) word.

Other men, similarly, do not want the midwife to get away from them, to slip beyond their grasp. On the ministerial level Silhouette, the controller general, and two other ministers of state, Bertin and Ormesson, have repeatedly explained that because of military expenses no regular yearly payment to the midwife from the Royal Treasury is possible. "The problem is that the time and circumstances are not propitious for obtaining new favors at cost to the state."[6] But this is only part of the reason for the denial. She might start to take her position for granted. Ormesson in particular feels this way. "It would be appropriate to vary this bonus each year according to greater or lesser service this woman gives to the province . . . so that [the payments] are always regarded as graces

which, however small they may be, must nevertheless continually be earned."[7] Ormesson is going to make her sing for her supper, now and later.

The king's first surgeon, La Martinière, has the same desire to simultaneously approve and check her, and to reaffirm his superiority. If she is not sufficiently diffident to surgeons, he warns, she will be perceived by the profession as a menace, and ruined. "Her machine has its merits for speaking grossly to the eyes of women from the countryside who would not be able to obtain more solid instruction. But in the opinion of the masters of the art, it lies always far below the knowledge furnished by good theory."[8] The intendant of Auvergne, the marquis de Ballainvilliers, who understands the midwife quite well and knows how good she is, has quipped to Versailles that surgeons are clearly threatened by her or they would not seek to disparage her. But even he believes she must be reminded of her place. He is genuinely supportive of her and extremely proud to initiate in his province this pilot program. As one of the first architects of her planned road show, however, he introduces a decisive twist that will have lasting impact. From the beginning he stipulates that the midwife must teach not only village women but regional surgeons as well. The king's brevet mentions nothing about the training of men, but Ballainvilliers has decided men would be safer depositories for the machine, better able to perpetuate her method. Otherwise a vast, controlling corps of exclusively female teachers would be created. Male surgeons learn faster than women, he asserts, and so should be guardians of the obstetrical models, which they will use when they in turn become demonstrators after the midwife's departure.

Ballainvilliers has certainly finessed this. Female students will now learn to practice, but never to instruct. The true professors, the ultimate possessors of the spoils, will thus always be men. A copy of the mannequin must be kept untouched in the Hôtel de Ville of each town where a surgeon disciple plans to give his courses. This will serve as an enduring reference, for the demonstration models suffer wear and tear and will need to be repaired and rebuilt according to the pristine original. To the suggestion from a doctor in Brioude that this system might fail, that women might hesitate to take lessons from a "garçon," Ballainvilliers replies impatiently: "Those who know and truly love the good will not sacrifice it to a displaced modesty and will go in search of it wherever it is."[9]

He is wrong. The courses set up by surgeons for midwives in nearby Ambert, Arlanc, Aurillac, Brioude, Mauriac, St. Flour, and Thiers attract mostly male students, and not very many of them either. Within a few years these classes will die out completely.[10]

What is the effect on Le Boursier du Coudray of all this engineering of her mission by men? She seems not to be bothered in the least. If she wants to call attention to gender imperatives in her personal or professional development, this would be the time. She could parlay her prominence into something more, defend midwifery from encroachments by men, engage in the period's major debates on education and women's intellectual capacity. Still a "demoiselle" according to the brevet, she could celebrate economic independence and alternatives to marriage. But doing so would destroy her chances for success. Why frighten precisely those people who give her this unique opportunity? Far from flaunting her spinsterhood, she pretends to be married, renaming herself "Madame" to conform to a familiar image and set men at ease. To preserve this unprecedented place for herself in public life, she can easily accept a few conditions. She is, of course, the ultimate beneficiary of this strategy, and she knows it. Compliance will earn her the freedom to do something singular. The royal brevet authorizes her, as no other woman has ever been, to represent Louis XV's will throughout the kingdom. It gives her carte blanche to travel freely "wherever she judges appropriate." From now on she sees herself as a man of action. She is not at odds with male domination in medicine and politics—as long as some very special room is made for her, as it now seems to be. She will make history.

Over the last decade, then, a profound metamorphosis has been taking place. The midwife seemed restless in Paris, but during these Clermont years she has honed old skills and discovered new ones, developed a courageous vision and a strong sense of calling. Her evolution has led from private practice to public service, from monotonous routine in Paris to mobility and adventure in the countryside, from personal mentoring of an occasional apprentice to group teaching of hundreds by means of an innovative pedagogy, from relative obscurity to celebrity as the trusted agent of His Majesty. Once a neighborhood healer, she is about to become a national star.

Ascendant now, she need no longer address the king's men as "Monseigneur" the way she did Ballainvilliers in the Abrégé 's dedication, but simply as "Monsieur." She and they are patriots, doing

the monarch's bidding together. Hence her unquestioned assumption, that we have already seen in her earliest known letter announcing her mission in 1760 to all the intendants of France, that she is unassailably their equal.

16—

Traveling for His Majesty:

Moulins, November 1761

Mme du Coudray—she has now shed her former name—has just finished her first invited teaching visit in her new capacity as the king's official emissary, one hundred kilometers north of Clermont in Moulins. This Bourbonnais region feels harmonious in late autumn, with its low-roofed farm houses and narrow snaking valleys. Over the centuries Moulins's imposing chateau has attracted numerous kings of France, perched high as it is above the rich town. A grandiose stone bridge, one of the greatest engineering feats of Trudaine's administration, attaches the city to its faubourgs .[1]

The midwife has been here since the beginning of the year, at the enthusiastic invitation of the intendant Le Nain, who learned a lot about the childbirth courses and about du Coudray herself in an exchange of letters with Ballainvilliers.[2] (Such intense lateral correspondence between intendants is noteworthy in this supposedly centralized administration, and in the case of the midwife will become a common practice during the next twenty-five years as they jockey for positions on her itinerary.) Le Nain appreciates her enormously. Enthralled by her talent and person both, he feels lucky and proud to be among the first to secure her services, for every intendant has by now received the letter in which she presented herself to the world. He has had the perspicacity to snatch her up before she gets too far afield, has even housed her as his guest in his own official residence,[3] and has printed a Mémoire sur les cours publics d'accouchements . Together they are sending this brochure around to all his colleagues, as a model for how her teaching in each new region should be organized. It is the first endorsement in her portfolio, and she will continue to use it to introduce her method of instruction for many years to come.

Le Nain's Mémoire is a detailed advertisement for du Coudray's work in the "conservation of citizens."[4] It first describes the unnec-

essary loss of productive subjects caused by ignorant midwives, the death of mothers and babies, the huge number of maimed children and women so mangled in their first delivery that they are incapable of bearing children again. "It was very easy to feel the extent of this evil, but very difficult to find a remedy," for most highly trained midwives who might have been helpful refuse to live in the "miserable countryside." But du Coudray, as "inventress" of a teaching machine, came to the rescue. Here in Moulins, Le Nain writes, "the infinite good she has brought has far surpassed our hopes." He offers himself as a consultant for anyone who wishes to learn more about du Coudray's services and his successful formula for the running of the course. The midwife's stay, including rest periods before and after classes, lasts about three months. The king pays only for the establishment of the course itself. Communities must provide for their own students; lords, parish priests, subdelegates, and magistrates in charge of each town should all actively recruit suitable candidates to come profit from the "bountifulness of the king."

All this is not, however, as easy as it sounds. Here Le Nain betrays the typical intendant's condescension for his rural charges. "We know only too well the indolence of the provinces even for the most obvious good, if it requires the slightest expense." One must insist, never give up, write letter upon letter, until the money is finally raised. Such repeated efforts on Le Nain's part brought eighty subsidized students to du Coudray's first course in Moulins; the second, with seventy, was slightly smaller because the timing conflicted with harvesting and many women were not free to leave their farms. Thirty-six or forty livres amply support such simple women during the course and even pay for their certificates at the end. Some students show no aptitude and are sent home; a few truly stand out. The majority learn just the basics, but this suffices to make them extremely useful in their villages. The teacher works them hard, yet she has realistic expectations and does not intimidate. Classes take place six days a week all morning and all afternoon and last two months, so that every student has plenty of time to listen to the lectures and then practice each maneuver repeatedly on the machine. There is even some training in live births as well; indigent women of the town, attracted by the midwife's enterprise, volunteer to be delivered by the best in the class while the teacher

comments and the others look on. The midwife will, of course, not allow any woman to graduate whom she finds inadequate to the task.

"The gentleness and patience of Madame du Coudray, the singular talent she possesses to make herself loved, is what contributes the most to spreading the fruits of her lessons." Le Nain is struck by how these young women are drawn to her, how she can attract and spellbind. He adds a further incentive: prizes for the three best students. Graduates leave the course armed with a special license to practice as midwives, approved by the Moulins surgeons for a tiny fraction of their customary charge. Le Nain is especially grateful to these men for cooperating, not a thing to take for granted; the tender vanity of surgeons will be an ongoing problem.

Du Coudray herself has been paid 300 livres for each month of her teaching, and Le Nain suggests an additional 600 as a bonus at the end. Each machine costs 300 livres to construct, which some towns pay to the midwife not in silver but in the form of a gift worth a still higher price. Le Nain says that "these presents please her much more than money, because she regards them as emblems and as testimonies of her successes." He suggests that provinces with an easier tax burden, the pays d'états , should be even more generous to du Coudray when her travels take her there. Her motive, "not interest, but . . . an ardent zeal for humanity," should be encouraged. All must work together "to conquer the indifference of people for anything without instant results. . . . It is true that M. Le Nain made it a capital point to support this establishment, that he neglected nothing to encourage the Mistress and her Disciples, that he barely let a day go by without appearing at the course; this method succeeded for him, and he thinks it essential to follow."

The Mémoire is a disingenuous maneuver on Le Nain's part. It does indeed promote the midwife's work, but it accomplishes two other significant things as well. First, it unabashedly flaunts, to authorities at Versailles and elsewhere, this intendant's good behavior. He has been totally attentive to the fledgling mission, rallying loyally to the king's wishes. Second, it states baldly that women are entirely to blame for the population crisis, conjuring up the specter of filthy peasant crones and superstitious mutterings. Du Coudray's Abrégé had been somewhat more evenhanded, implicating foolhardy surgeons as well as matrons in the carnage. But she has not been forceful on the issue of protecting women, having acqui-

esced with no sign of struggle to Ballainvilliers's idea of making male surgeons the exclusive depositories of her machine. Now, once again without apparent objection from her, Le Nain has placed her in an adversarial role against other women, has worded things in such a way that du Coudray seems co-opted into the patriarchal camp.

Why has the midwife agreed to this? In order to generate support she must distinguish herself from the feminist midwives of her day, whose polemics have reached fever pitch lately. Just last year the Englishwoman Elizabeth Nihell, who trained in the early 1730s under Mme Pour at the Hôtel Dieu in Paris, published her Treatise on the Art of Midwifery: Setting Forth Various Abuses Therein, Especially as to the Practice with Instruments . An impassioned attack on male obstetricians, this book is creating a huge stir in London and now, ever since its review in the Journal encyclopédique , is much talked about in France as well.[5] Nihell is deeply convinced that men have no place in the birthing business, that they are in it only for greed and gain. She is particularly hostile to their use of forceps and other instruments, their rash, rough, rushed approach. She witnessed two thousand births during her training at the Hôtel Dieu, all but four safely concluded without the help of any man.[6]Accoucheurs are, she claims, a "band of mercenaries who palm themselves off upon pregnant women under cover of their crochets, knives, scissors, spoons, pinchers, fillets, speculum matrices, all of which and especially their forceps. . . . are totally useless."[7] Nihell makes venomous personal attacks against some very distinguished surgeons of the day. Far more deaths, she argues, are attributable to the presumption, interference, and clumsiness of men than to the ignorance of women.[8] Midwives must reclaim their "ancient and legitimate profession." They should never even teach men their art because these men will turn and betray them; male hearts are as "false as they are ungrateful."[9] The English author speaks of a powerful female bonding, "a certain shrewd vivacity, a grace of ease, a hardiness of performance, and especially a kind of unction of the heart, . . . that supremely tender sensibility with which women in general are so strongly impressed toward one another in the case of lying-in." Male practitioners—"cold," "awkward," "stiff," "unaffectionate, perfunctory"—work like technicians on women, whereas midwives work with women—this is what the word literally means—guiding, caring, boosting morale.[10]

Nihell's sarcasm and anger contrast markedly with the silence of

du Coudray, whose instincts have told her from the beginning not to defend a separate professional space for women. It is of course true that by training women she enables them to move from marginal means of subsistence to greater financial security and social esteem, but du Coudray never says so. Such fighting words would only alarm. Instead she pledges to train any and every person willing to join the government's drive against infant mortality. This is the language to which administrators of the monarchy will listen and rally. Her avoidance of explicit female advocacy, her apparent denial of such identification, certainly seem to compromise her feminist credentials. But that she might be seeking similar goals by other means has to be considered. Remember that long before her celebrity she freely chose a profession that brought her intimately close to other women. They are never very far from her mind, and the bonds are there, articulated or not. By using skill, not gender, as the key to her image as a practitioner, by stressing competence and control as criteria that elevate her students above the rest, she is suggesting that obstetrical ability can be cultivated in any person. The leveling implications of this message are powerful, and may serve "her women" better in the long run than Nihell's belligerence.

Du Coudray, then, allows Le Nain to shape and reinforce her role. Invigorated by this first experience performing for such large numbers of students, 150 in all, she presses on now, entirely committed to the nationwide tour. Le Nain's is the kind of enlightened local support she realizes she will need but will not always find. Meanwhile this intendant, truly smitten, never stops praising her—always mindful, of course, that by supporting her the king's administrators can help not only the country but also themselves. Even years later when taking the waters at a thermal spa where he meets a colleague, he will rave about her mission, inspiring the other man to invite her to his region immediately upon returning home.[11]

17—

Boasts, Rebuffs, and Boutin:

Chalon-sur-Saône, 19 March 1763

Monsieur,

Monsieur the Controller General, attentive to all that contributes to the good of the state, especially to conserving its subjects, orders me to have the honor to write to you about

the establishment of educated midwives for the security of villages. I am sending you the Mémoire of M. Le Nain, which is as interesting as it is instructive and which will spare me having to tell you all the details of this establishment. I have completed all the engagements I had with M. de Villeneuve, whose happy successes have brought him as much admiration as gratitude from the citizens. I am free, Monsieur, and I urge you to give me an answer as promptly as possible. I know the secretary of state desires that I bring the good that I do particularly to your province. I must give him an accounting of the time I spend fulfilling his wishes. He does not permit me to waste any. He would even want me to be everywhere if that were possible. You see, Monsieur, that your delay in replying would make me lose time that is too dear to the good of humanity, and I would worry that the minister of state who honors me with his benevolence and with his confidence will suspect my zeal of a slackening of which I am not capable.

I have the honor to be, with respect, Monsieur, your very humble and very obedient servant

du Coudray[1]

It is spring. The midwife, writing today to the intendant of Bordeaux, has spent the last year and a half traveling and teaching in Burgundy, the region administered by J. F. Dufour de Villeneuve. Courses have gone well in Autun, with its Roman gates and theater; in Bourg-en-Bresse, with its unique timber-built farmsteads and "saracen" chimneys; and now at Chalon-sur-Saône.[2] This city, where Peter Abelard famously died—the locals talk of it still—has been an important market town since the Middle Ages; each year before Mardi Gras the fair attracts trappers from all over to trade in pelts. Extraordinary wines, cultivated for centuries by Cluniac and Cistercian monks, enhance this region's fame.[3]

Du Coudray is very pleased with herself, indeed elated. During the six invited courses taught in this region she has trained more than four hundred students.[4] Some, just recently examined by the surgeons of Dijon, passed their tests with flying colors.[5] She sees already what a difference her teaching makes, how highly she is regarded. Increasingly privy to information and directives from Versailles, she is not always as tactful as she might be in handling these confidences. It is thought, for example, that the Bordeaux region is

unusually backward in its practice of midwifery. Upon learning this, the midwife decides she should hasten there next, even though it is far away. In this overzealous letter du Coudray therefore foists herself rather boldly on Boutin, the intendant of Bordeaux, crowding him, rushing him to answer, insinuating that he requires her services more than do others, brandishing Le Nain's Mémoire so that she need not bother to explain herself, anticipating how much Boutin's hesitation will inconvenience her, blaming him in advance for slowing down her mission of salvation, almost threatening to report him. Carried away by her increasing importance, heady from the authority vested in her, she makes her first diplomatic blunder.

Deeply affronted, the administration of Bordeaux reacts badly to this woman's imperious tone, her brazen self-promotion. Is it because a female presumes to speak for the government? Is it her insulting suggestion that Bordeaux is in worse shape than other areas of the country? Boutin does not feel it is for her to judge, and finds her display the height of insolence. The intendant's secretary responds that they will not be needing her services, thank you. "We can very well do without Mme du Coudray at Bordeaux."[6]

It is not as simple as that, however. What Boutin fails to realize is that one does not refuse the services of the king's midwife and get away with it. Just last month the Treaty of Paris put an end—albeit a humiliating one—to the Seven Years War; ministers can therefore pay more attention to domestic issues now. France, licking her wounds, her international prestige severely damaged, is determined to put at least internal affairs in order. The controller general Bertin immediately defends du Coudray and presses Boutin to explain his reasons for snubbing her. What has caused his embarrassing stance against the royal midwife? Has some ill-informed party prejudiced him against this worthy woman?[7] Reprimanding him and urging him to see the situation clearly, the minister suggests Boutin try straightway to undo the damage of his rebuff.

And the damage is great. Du Coudray is coming to see her work and the good of the nation as one and the same. She experiences Boutin's slight as both a personal rejection and evidence of the man's political obtuseness. He is trying to obstruct the bien de l'humanité , a phrase she first uses in this letter but which is to become her rallying call, a synonym for her mission. As she does not suffer fools gladly, she will hold a grudge against Boutin for years. It will

give her enormous satisfaction to humble him as an object lesson for others who might neglect to pay her the proper respect.

18—

Turgot:

Tulle, 29 December 1763

Rather than put up with the indignity of trying to go where she is not wanted, du Coudray has accepted an eager invitation from Turgot, the energetic thirty-six-year-old intendant of the Limousin, and traveled to the capital city of Limoges in late spring. This land is a mosaic of greens with its meadows, grass, dense forests, and fern fronds, yet it is a poor, backward area for agriculture; most live on a coarse bread made from buckwheat, rye, or barley oats. The only plentiful crops are chestnuts and coleseed.[1] Turgot is pressing hard to introduce a new food, the potato, but so far it is not catching on.

In this intendant du Coudray has found someone whose zeal surpasses even her own. Already now, more than a decade before he will become controller general of France, Turgot is undertaking numerous reforms in the area over which he presides, initiating new farming methods and improving roads, bridges, and mail transport, but especially making such taxes as the taille and the corvée less burdensome for the poor. He has brought du Coudray here to his region with great fanfare, first to Limoges, an old city of mudwall houses whose roofs jut out so far that one can barely see the noonday sun. The locals, however, are not known for politeness or openness to new ideas. A contemporary guidebook even comments that the intendant, who has his main residence in this town, will, alas, not be much enriched by his contact with the Limousins.[2]

And at times his task is thankless, but Turgot is not one to give up. In August he had bristled at the small turnout for du Coudray's first course, castigating his underlings for not advertising her coming or organizing things properly, berating the "deplorable nonchalance" of subdelegates, priests, and parishioners who had failed to find enough students to take advantage of this stellar opportunity. He shared his impatience with officials in Paris. "I will not hide from you that I am afflicted that they did not profit from the important service I wished to render. I want, however, to make it available again so they may make up for their negligence."[3]

Realizing then that a favorable welcome for the midwife could not be taken for granted, Turgot has ever since been relentlessly shaming both secular and religious leaders of surrounding towns into raising enough money—he estimates a mere 28 livres can support a student in town for two months—to send women from as many parishes as possible to the courses. When du Coudray moved from Limoges to Tulle to begin teaching a new group of students on 15 November, the intendant had been careful to anticipate and compensate for the notorious stinginess of this town.[4] Tulle residents have a reputation as quibbling, peevish, and disobedient.[5] Turgot has decided to entice students by promising them exemption from taxation on all extra earnings from their future profession as midwives.[6] This time he is determined that the course succeed, and he will brook no argument. It is not, however, the midwife's feelings that are paramount in his mind. As he phrases it in his letter, her courses are an "important service I wished to render." If they go badly, in other words, it is a reflection upon him. That is his prime motivation.

Meanwhile, Boutin in Bordeaux, who had initially wanted nothing to do with du Coudray and her courses, is paying dearly for his "shortsightedness" and is obliged now to gather information about her and attempt to bring her to his region after all. It is winter, and Turgot is on his rounds touring the area near Angoulême when he receives a letter of inquiry about the midwife from the once-reluctant, now repentant, Boutin. Turgot answers with this assessment:

I believe her work extremely useful and her manner of teaching the only one accessible to country women. You will perhaps find her person rather ridiculous with the high estimation she has of herself, but this will probably seem to you, as it does to me, quite unimportant. The essential thing is that she gives useful lessons, and hers are very useful. Her sojourn in the province is a bit expensive, because I give her 300 livres of stipend each month, not including the cost of her voyage and the transport of her trunks. I also have the cities provide her with lodging, wood, candles, and household utensils. Add to this the purchase of some of her machines in order to establish perpetual courses that I will entrust to some surgeons. I figure all of this will cost the province about 8000 livres, but I consider them well spent.[7]

Why, despite his recognition of her exceptional work, does Turgot depict du Coudray as a ludicrous character? Is this merely a misogy-

nistic reaction to a self-confident woman? Or is the midwife behaving in an exaggeratedly boastful manner at the moment? Probably both. Turgot shares, almost surely, the deeply assimilated prevailing assumption that a strong, capable woman proclaiming her own worth somehow transgresses the bounds of normalcy. But the fact is that du Coudray is also tooting her own horn excessively right now. Gravely wounded by Boutin's rejection of her services, she has recently been hit by yet another worry: the war may be over, but the Treasury is overwhelmed with debts, and there has been a major shake-up at Versailles. Will the new ministers in power, whoever they are, regard her mission favorably and continue to facilitate things for her? Her protector Bertin is being replaced. Will her cause be forgotten with his departure? She has been corresponding with him lately about her fears and preoccupations in this regard.

Today, as the new year is about to begin, she unburdens herself to her original supporter, Ballainvilliers in Auvergne. Writing at Bertin's suggestion, she is in a state of agitation. Misspellings are rampant, and the hand is shaky:

Receive please the remembrance of all the best wishes I feel for you. You could never doubt their sincerity, since so many sentiments come together to form them and lead me to assure you of them. . . . You will, Monsieur, contribute to the decision of my fate by please providing me with a certificate for the good works that my students did in Auvergne. The circumstance is most essential, according to what M. Bertin tells me. His retirement at first frightened me, but he was good enough to inform me that I must send him as soon as possible certificates from all the provinces where I set up this establishment and that then my future would be secure. If, Monsieur, the new Controller General is known to you, I hope you will be kind enough to speak to him in my favor. I always count on your goodness.[8]

Suddenly du Coudray senses her vulnerability in the shifting political winds. In some ways she believes she holds the upper hand. The intendants, though at the top of the provincial hierarchy, seem in no way superior to her. They are removable, and she knows they can be reassigned or dismissed, and often are, when they fail to do their job properly. If she reports administrative obstacles thrown in her path or relays an unfavorable impression of her stay in a particular region, it could be very damaging for these men. The public embarrassment of Boutin is a case in point. But now everything seems much more tenuous and complicated. Bertin has advised her

of new measures she must take to guarantee the security of her position. She will have to solicit testimonials of her accomplishments and successes from these very intendants. She, in other words, is now as dependent on them as they are on her. She needs enthusiastic endorsements from each province she services, valorizations of her efforts that will henceforth constitute a written dossier assuring her of future teaching engagements. Bertin believes such a portfolio of praises is necessary and will protect her.

What this means, of course, is that her work as a teacher, however outstanding, is not enough. She must impress during her time off as well. The pressure on her to promote herself, especially after Boutin's rejection and Bertin's disgrace, is enormous. What if other intendants get it into their heads to turn her down also? She must persuade them of her merits, must advertise her superb record thus far. The parading and strutting that Turgot balks at is thus something rather new, a function of her uncertainty about continued sponsorship and of her dawning awareness that despite the King's brevet, she will need ceaselessly to muster support for herself. Because in her patriotic zeal she believes her job so consequential, it seems beneath her to have to ask for help or indulgence. Yet she is now beholden to these men for their accolades. However impatient she might be with some of their prevarications or obtuseness, she must be solicitous and humor them.

This, then, is the delicate balance of power to be negotiated between the midwife and the intendants. It will be a complex dynamic, resulting often in mutual adjustment and cooperation.

Though not always.

19—

"Her Unendurable Arrogance":

Angoulême, 30 July 1764

Du Coudray has been teaching within the ramparts of this hilltop city for many months. The surrounding countryside is luminous and misty now in summer. She came from Tulle over the soft rolling heather-covered hills and marshlands in a stagecoach drawn by four horses. The official in charge of her stay here has been watching her closely. They do not get along; she suspects him of having been the one who turned Boutin against her in the first place. He is both fascinated and disturbed by this powerful, complicated woman. The

tardily penitent Boutin is now desperately trying to make amends and create a strategy for wooing the midwife to Bordeaux, and she enjoys watching him grovel. Having contemplated Turgot's response to his inquiry, he has next asked the subdelegate of Angoulême to fill him in on du Coudray's work and on her present frame of mind. Today the man obligingly writes his answer, with attempted fairness and objectivity, "as a good citizen and without any prejudice." She has angered him—"I have reason to be personally very unhappy with the conduct of this woman"—but he gives credit where it is due and grants, reluctantly, that she has great "experience, devotion. . . . to her profession, and natural gifts."[1]

The journey, he explains to Boutin, was expensive, as each of the four horses cost 6 livres a day and their return trip must be paid too. The midwife requires two months for the course itself, fifteen days to prepare before it begins and another fifteen to rest after it is over, so the town pays 900 livres in bonuses for the three months, and another 600 for lodging. Four machines cost 1,200 livres, and a copy of her book is "indispensable" for each student. She sells the book directly for 40 sous a copy, but he proposes that an "economy" printing of two thousand could be done—he has of course not consulted her on this—so that each one would only cost 5 sous. Thus a little over 3,000 livres, he estimates, will pay for du Coudray to train eighty women and twenty surgeons. On the subject of her "very ingenious" obstetrical model he somehow feels more inclined to respect her proprietary claims than in the case of her book. He explains about the model: "being of her own invention and composition, she seems to have an exclusive right to make it and distribute it." Imitations are inferior anyway, and "it would be a kind of larceny against her to deny her the considerable profit she makes on the sale of her machines." There is no substitute for du Coudray herself either; the "honest truth" is that only she really knows how to go about this teaching properly.

So much for the work. Now the person herself. "The difficulty will be to find out if, still today, the vanity of Mme du Coudray, humiliated by your refusal to receive her in your generality when she counted on going there, won't lead her to the stupidity of rejecting the invitation that you would make. For she has her imagination so full of the superiority of her talents that she often puts to the test the most resolute patience by the explanation she is always ready to make of her merits and by the recitation of her honors. I am

understating, because one must even speak to her of the homage she claims was rendered to her in the cities she passed through, so that whoever does not render her similar homage appears in her mind as a mere automaton, having nothing human but the shape."

It is, the writer continues, du Coudray's firm conviction that Bordeaux, like all other generalities, is contracted to receive her, and that Boutin's refusing her was a breach of faith, a "breaking off" of that solemn engagement. He now recommends strongly that Boutin charge someone else with the negotiations so as not to compromise himself. He even suggests a particular person whom the midwife trusts. She might then give in. "Despite her unendurable arrogance, she knows she needs to teach to live, and I have seen her here reduced to great embarrassment when resources for the voyage . . . were lacking. She maintained that she wanted nothing more than to be able to return to Paris, but at the same time she was writing and having people write for her far and wide to find some region where they would welcome her." If she has something lined up as a result of this feverish correspondence, in other words, "she might play hard to get [faire la difficile ]. But if she has nothing else, she might consider herself lucky to come to you." Boutin should, the letter ends, get someone new to approach and flatter her, to butter her up by explaining that they have finally persuaded him of her indispensability.

Here, then, is how one critic sizes her up. Clearly put off by her pushiness, he finds nothing admirable in her vigorous proselytizing and dislikes her histrionics. Yet he perfectly understands how essential her work is, and even sympathizes to some extent with her desire to protect her financial interests. He paints a poignant picture of her neediness, her temporary loss of will, her confusion. Just a few years into her traveling mission, he believes he has detected some faintness of heart. He knows it would be best for both Boutin and du Coudray if, still saving face, they could come to terms. Hers is the greater vanity, it seems, the noisier bravado, but in this man's estimation it is really a thin and rather fragile facade.

20—

The Thrifty Laverdy:

Fontainebleau, 16 October 1764

Louis XV moves around often between his many palaces in the Paris region—Compiègne, Fontainebleau, Choisy—taking with him

his council of ministers and other advisors. It is outrageously costly to maintain all these royal households, and there are rumblings everywhere about the monarch's extravagance. The ministers in charge of finances can scarcely keep their heads amid the whirl of hunting parties and feasts, but they try to stay focused on the needs of the country, try to tame royal excesses, try to support worthy causes.

The new controller general, Laverdy, has been told all about the midwife, and he is impressed. She must have gathered and forwarded to him, as Bertin suggested, many rousing recommendations written by officials in the towns where she has taught so far. Laverdy is a stern and frugal Jansenist, rather partial to the parlements in their battle against royal spending. But the war is now over, financial constraints have relaxed slightly, and this reform-minded man means to translate his admiration for du Coudray into a more stable financial arrangement for her. Today he sends to all intendants a letter stressing her generosity in traveling so extensively for the cause. Not given to hyperbole, Laverdy nonetheless casts du Coudray's mission in grand terms: she does far more than save subjects for the king; she preserves the whole human race.[1]

Laverdy, a keen accountant and crisp administrator, plans efficiently. He wants the midwife to be guaranteed 8,000 livres a year. He cannot, any more than his predecessors, commit the Royal Treasury to this, so he wants the money raised by the provinces, as it is they that reap the fruits of her labor, the benefits of her instruction. This is an artful argument, of course, because the monarchy is the big winner no matter what Laverdy says. In fact a great struggle is brewing between the crown and the countryside. The controller general, as an agent of the monarch, is pressing for the provinces to shoulder this fiscal responsibility, because the crown, by sending the midwife around, has done its share. Each province need give only 270–280 livres to the common fund, a small price for this invaluable training. A diligent du Coudray should manage to complete what remains of her tour de France in six or seven years, Laverdy figures; she requires three months for each course, so she should be able to "do" four provinces each year.[2]

But wait. Laverdy may be good at arithmetic, yet the midwife is not a ticking mechanical clock. He is dealing with a human being, and an opinionated, demanding one at that, who is willing to work very hard but insists on her rest in between and on everything being set up exactly to her specifications. Hers is a grueling job, and

she goes about it in her fashion, proceeding without undue haste. Being used to major hardships, she expects minor comforts by way of compensation. If anyone were to tell Laverdy that she would still be traveling on her mission two decades from now, that he has grossly underestimated the time it will take, the thrifty man would be horrified. As it is, he will have trouble accepting even the shortest delay or extra expense. He supports her, but finds upsetting any vicissitudes of life that muddy his careful calculations. And the business of birthing is notoriously incalculable.

Also, this amount of 8,000 livres is merely a hope, not a promise. And it is unrealistic. Laverdy is counting, naively, on provincial cooperation to arrive at that substantial sum. Just two months ago, in August, he issued an edict whose purpose was to bring more uniformity to the municipal administrations of the realm, to crush the old city oligarchies and reform their finances. Seemingly oblivious to how unpopular these ideas are, he feels he can press the regions to underwrite du Coudray's mission.[3] Here, too, he has seriously miscalculated.

A major rebellion against royal authority has been taking shape in those provinces with a parlement and an états , or assembly, of their own. Not only does France have privileged groups—the clergy and the nobility—but it has these privileged territories as well, areas that function with considerable autonomy, enjoying special exemptions and rights. These pays d'états , as they are called, are therefore often refractory to progress, innovation, and considerations of general interest. The intendants there are having great trouble trying to implement the will of the king and his ministers, as the experience of Le Bret, intendant of Brittany, demonstrates. He wants to oblige Laverdy and support the monarch's midwife but is clearly intimidated by the local états , who have endorsed instead a male surgeon. Du Coudray, he explains, will need to jump through hoops, will need to come in person and do a dazzling demonstration before the états will even consider her. And there are still no guarantees after this trial; rather, he sees a large chance of rejection. He knows the états will object to the 270 livres Laverdy is requesting. All he can do, despite his supposed influence, is "mediate."[4]

So the plot thickens. The midwife will of course continue to court and cultivate ministers and royal administrators, but she will soon realize that no matter how fervently they support her, a whole new

set of political obstacles will need to be surmounted. And often they can't be. Provincial bodies now actively contest the crown's authority, aggressively seek to destabilize and desacralize the monarchy's effective and symbolic center. Nothing is sure or steady in this job, when being "sent by the king" turns out sometimes to be as much a curse as a blessing. Her own loyalties do not waver, but it is a shocking discovery for her nonetheless that His Majesty is not everywhere revered.

21—

Sounding Her Mood:

Bourdeilles, 12 December 1764

As a special favor to the former minister Bertin, du Coudray has gone to teach the women on his estates in this magical town in Dordogne, where the river flows beneath a Gothic bridge and the seigneurial mill juts out defiantly like a boat's prow, the château anchored above to an enormous rock shelf. Even here—or perhaps especially here, among the cliffs and valleys of Périgord—the hapless Boutin is pursuing the midwife, for she is now very close to Bordeaux and he does not want her to elude him.

This chase has become a matter of pride and political survival. Boutin has, through his inquiries, actually come to value the training du Coudray offers, but mostly he is now just obsessed by the need to clear up the mess he has made, to erase all trace of his earlier insubordination, to no longer stand out as the one intendant too dense to recognize her importance. He knows she will refuse to come directly to him no matter how much he tries to ingratiate himself, as he has explained wearily in a summer letter, but perhaps he can begin to win her over by enticing her next to the town of Sarlat a bit further south, and thence to Bordeaux. She is presently planning to go north to Poitiers, and he hopes to intercept her before she slips away. But to ensnare her before her departure, subterfuge will be necessary. She must never know the request comes from him.[1] He asks a friend of his in Bourdeilles to casually suggest Sarlat to her and "take a sounding of whether she is disposed to it." In the meantime Boutin wants to procure her props to use in his region, even if he cannot get her in person. He instructs his contact to buy one of her "ingenious machines" and "the greatest number that you

can of copies of her book, again without her suspecting that this purchase is being made for me. It must be done by an intermediary. I have reasons for this that it would take far too long to explain."[2] This, then, is the plan.

Except it does not work. Du Coudray sees through this scheme immediately. She turns the Sarlat proposal down flat and gives all her energies to teaching the students in Bourdeilles and overcoming the antagonism of the local surgeons. She knows she has the new controller general's endorsement, and today Bertin informs her that he too still stands fully behind her, however diminished his role may be. He is particularly touched that she is giving her precious time to his townspeople, and vows to do all in his power to insulate her from detractors. "It would not be possible, or even fair, that you make war at your own expense. It is sufficient that you give your time and your pain, and we should all be most grateful."[3]

Probably because of this heartening reiteration of support, du Coudray figures she can afford to shun Boutin a little while longer. Delighted to be the unattainable prize in his quest, to leave his increasing need for her unrequited, she is perhaps taking things a bit too far. But keeping such men in check is part of her mission, for she must have their cooperation. She is not frivolous, merely eager to test the extent of her power with the intendants—which is considerable if Boutin's conduct is any indication. Rather than ignore her or give up in exasperation, he persistently keeps track of her movements and moods, involves numerous others in the subtle orchestration of his pursuit, plans continually new ways to obtain her. That she must relent eventually and go to Bordeaux is a foregone conclusion. Even the keenest acrimonies are apt to fade. For now, though, she can hold out at no cost to her. If anything, her recalcitrance increases her prestige. Boutin's predicament is getting to be a famous story.

22—

Delivering "Like a Cobbler Makes Shoes":

Poitiers, February 1765

Du Coudray is no longer alone but is now traveling with an entourage of four. If she was accompanied before, none of the observers reporting on various aspects of her mission has so far mentioned the fact. Now, however, her arrival with her company has

created a sufficient stir and spectacle to be noticed.[1] They have had to climb steeply to reach Poitiers, this awkward, poorly built high platform of a city, and it proves too much of a strain for the full coach. It is easy to watch and count visitors if they empty out of the carriage to lighten its load on the flank of the pitched slope, and walk beside it for the last part of the ascent.

This strange town actually has some workable land within its Roman walls.[2] The intendant, de Blossac, had difficulty initially in rounding up students for the first course despite numerous posters and printed circulars.[3] He had found lodgings for du Coudray in a vacant house that was formerly used for recruits going to the colonial islands. Frightening rumors buzzed at first, fanned by the jealous surgeons, that students attending the midwife's courses there would be trapped, kidnapped, and shipped off to Cayenne! This misconception has been cleared up, however, and eighty have taken the first course, with still more clamoring to attend the second. The intendant is providing funds for those who travel far, though not for others who already reside and cultivate the land in Poitiers. Eighty is about the maximum du Coudray thinks she can teach at a time, for each woman needs a long turn manually operating the machine under her close supervision. At the start of the lesson every student receives a number, and they come up to work with her in that order. During breaks, or at the end of the afternoon, a répétitrice drills them orally on what they've learned.[4] The intendant is struck by how the midwife focuses on the product, the baby; only a few very general lessons are devoted to caring for the mother. The students, he reports, "know how to deliver like a cobbler knows how to make shoes; that's all that's necessary." They are taught to do good by producing goods.

In general the intendant is very pleased. Reflecting and congratulating himself, in a now familiar trope, on the great service he has procured for his province, he advises his friend and colleague Le Bret, the intendant of Brittany, to have du Coudray come there as soon as possible no matter how refractory "your interminable états ." She seems too good to be true, he muses. Wintering now in "horribly cold" Paris, huddled by the fire with fever, feeling sorry for himself because he is missing various festivals and concerned about his children who have measles, de Blossac is wondering if the midwife too might succumb to any weakness. Will she be spoiled by Laverdy's projections of financial security? A slight note of cynicism

creeps in. "I see only one inconvenience about which I'd say that the minister did not think, if it is possible that a minister doesn't think of everything. That is, to be worried whether this woman, seeing her future provided for, won't relax and save herself trouble, unlike when, her well-being and her recompense dependent on our satisfaction with her pains, she spared nothing to satisfy the public." On the chance that the midwife's efforts might soon begin to wane, Le Bret should get her right away before she starts to take it easier and cut corners, "before half-heartedness sets in."[5] But the terrible conflict brewing in Brittany right now between the parlement and the crown has escalated, and Le Bret finds his position far too precarious to push any more for the king's midwife at this juncture. He will store the idea, however, and make sure she comes later when the trouble dies down. He has no way of knowing that that will take more than ten years.

Viewing du Coudray's teaching as mostly mechanical, de Blossac seems to think that she, like her machines, may wear out with overuse. In fact, she shows no signs of winding down at all. On the contrary, the midwife is making a lasting impression here, as the local newspaper, the Affiches de Poitou , still testifies years later. (She is, by the way, becoming a favorite feature story in the provincial press wherever she goes.) In numerous villages women gather to review her book; those who can read do so out loud, the others listen attentively. They study the lessons and "meditate" on them together, taking the new teachings very seriously. Of course there are some negative reactions too. This reporter has no patience with what he calls the backwardness of small-minded peasant women who "can't imagine that anyone could learn anything outside the boundaries of their parish. . . . They prefer always to rely on midwives in their villages who have no other claim to fame than having made many women and children perish."[6] And a local surgeon will try hard to undermine du Coudray's lessons, claiming consensus among his colleagues that "this woman's courses were more dangerous than useful, as they trained demisavants who with no in-depth knowledge believed themselves to be her equals."[7]

The midwife, however, is growing accustomed to such inertias and jealousies and can take them in stride, knowing that her teaching here has made a huge difference, whatever some might say. Women giving birth in this Poitou region, before her arrival, fol-

lowed the local custom of walking around once the baby's head appeared, a terribly dangerous practice resulting in a high incidence of strangulation.[8] She has shown them the folly of this and many other things, so she is confident that her students here, both male and female, are learning well and enduringly. And this faith is to be borne out. One surgeon she trains here will be using her machine and method well into the Revolution.[9]

23—

Surgeons of the King's Navy:

Rochefort-sur-Mer, 30 April 1766

More and more surgeons are impressed with du Coudray as she travels now along the Atlantic coast through a series of port cities—Niort, Les Sables d'Olonnes, La Rochelle, Rochefort. When du Coudray teaches in the marshy inland port of Niort after leaving Poitiers,[1] she wins the undying devotion of a M. Saint Paul, surgeon-major in a regiment of the royal cavalry. He will take her course again and again whenever their paths cross. Years from now, after studying with her in Lorraine in 1774, he will reminisce about the "incomparable," du Coudray, "the most celebrated midwife who ever existed," a "divine woman" who "demonstrates so sublimely."[2]

He had not been so sure about her at first. "I confess to you," he tells a friend, "to my embarrassment, that before having seen for myself the astonishing effects I regarded her exclusive mission as an act of favor accorded by the ministers to an ordinary person. . . . Stuck in this prejudice, my regiment in 1765 was sent to Niort . . . where she had just given her course of instruction. Everyone was exalting the sublime talents of this woman; the enthusiasm was unanimous. I still had the weakness to think that people gave more credit to the novelty than to real merit." His regiment, however, had stayed in that area for three years, and he had the chance to witness many deliveries brilliantly executed by her students. They were all youthful and energetic women with no previous training in the art, and therefore "not numbed by habit and infatuated by their would-be worth like the old ones." Training the young, he recognizes, is just one more innovative feature of du Coudray's program. She wants to teach the uninitiated who can be formed by her from scratch. Another reason for targeting the young is that her students

will still have before them many "long years of precious service," making the teaching investment worthwhile. It is, Saint Paul emphatically agrees, an efficient way to generate a lasting network of expert midwives.

Du Coudray's reputation has been running ahead of her, her visit eagerly anticipated in these coastal towns. They make her welcome despite hard times, for the main commerce of this area had been with Canada, whose loss just recently in the Seven Years War ravaged the local economy.[3] She handles this series of lessons with particular dispatch. The city of Sables actually raises more money for her stay than can be spent, so swiftly does she complete the training there.[4] Then four months in La Rochelle, and she moves on to set up shop here in the port of Rochefort, a navy stronghold with its gunpowder works and cannon foundry, a center of activity for royal sailmakers, armsmakers, shipbuilders, and ropemakers. The king takes special interest in his naval hospital here and in his Hôtel des Cazernes, where three hundred marine guards are coached in all exercises befitting officers who aspire to serve on His Majesty's ships.[5]

But what a curious place for the midwife to be! Why would she teach here, given that these classes are exclusively male?

Passions are running high just now in favor of the monarchy, so du Coudray rides with pleasure on the current enthusiasm. For the king has at last asserted himself, after two years of repeated humiliations inflicted upon royal authority. Uprisings of parlements in the provinces and the capital started in earnest around 1764 and got quickly out of hand, these law courts declaring themselves the united defenders of the fundamental laws of the realm and spokesmen of the nation, remonstrating against all the king's royal edicts, refusing to register them or give them the force of law. Invoking historical precedent, they claimed something like a power of judicial review over royal decrees. Finally provoked, the king just last month, on 3 March 1766, went in person to Paris, solemnly assembled the judges in the Palais de Justice, and gave his séance de la flagellation , or scourging session. In this speech, a forceful statement of absolutism, Louis announced that he would tolerate no more disobedience from these intermediate bodies and reaffirmed that all authority in the realm was vested in him alone.[6] The strength of his declaration took everyone by surprise. His powerful words have been ringing

throughout France ever since. All this is still new enough that the reaction, the backlash, has not yet organized itself. For the moment, anyway, it is a good time to be the king's midwife, and du Coudray means to make the most of it by choosing to teach here in this royal stronghold.

His Majesty's naval surgeons, who invited the midwife, are extremely solicitous. The lessons here differ markedly from those she offers to women. They deal with obstetrical instruments and cesarean sections, tools and techniques female midwives are never to use, procedures they are never to do or even attempt, on pain of death. Since 1755 laws have effectively denied women access to all new technologies such as forceps and hooks. Surgeons, especially in Paris, are trying more concertedly than ever to exclude women from the cutting edge of the field of childbirth. Ironically, though a woman, du Coudray has special dispensation to reveal her knowledge of this forbidden area and to impart it to these members of the very profession trying to monopolize it.[7]

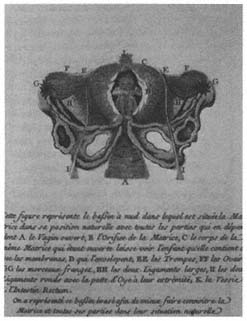

Today eleven of du Coudray's surgeon disciples compose a letter officially certifying how much they have been taught. "We first learned simple and complicated deliveries, then the way to extract children with the help of instruments in malformations of the pelvic bones, as well as to do cesarean operations, and the puncture of children's heads . . . in cases of hydrocephalus. Mme du Coudray accompanied all her operations with liquids, [to show] loss both of blood and of waters. She has skillfully detailed for us the signs leading to knowledge of pregnancies and miscarriages, and showed us all the infirmities of women, including cancer of the womb, all so well depicted [on her machine] that one could not better imitate nature. Which has perfectly convinced us that she rightly deserves the brilliant praises that are won for her everywhere by her great reputation."[8] The liquids mentioned—dispensed from an elaborate set of sponges, some saturated with clear and others with opaque red fluid—which make things so realistic, seem only to be used for the surgeon classes at this point. Soon du Coudray will adopt them more generally, referring to them as a "supplement" to the machine, and sell them for extra money.[9]

This curriculum, then, is much more concerned with death, with pregnancies that end in extremis, where a dead baby must be extracted from a healthy mother, or a live baby from a dying mother.

It is at this point, usually, that surgeons or doctors are called to the scene, after the midwife realizes too late that her client is in serious trouble. If some cutting or some killing needs to be done, if either mother or baby must be sacrificed to preserve the other, it is the men who intervene and decide which one will be saved. Where women are held criminally liable for making such judgments, male practitioners do it routinely, with impunity. It seems a dubious honor, but such is their prerogative.[10]

Du Coudray finds time to make some side trips. Among them is probably an excursion to nearby Saintes, exceptionally rich in Roman monuments and its cathedral built by Charlemagne.[11] Perhaps she befriends a printer there, because a few years from now a new edition of her Abrégé will be published in that town, an unlikely place to pick for book business unless you have some personal connection. The residents of some of the offshore islands, encouraged by her local explorations, have reason to hope she will come their way to teach, however briefly. A surgeon from St. Pierre on the Ile d'Oléron will remember the excitement over her proximity, then the disappointment when she did not visit. Deeply regretful that his isolated area missed out on her tour, he notes that "we received from no one any compensation for this loss."[12] Preachers in surrounding towns thank divine Providence for sending her to their region and know that heaven will grant her lasting prosperity.[13]

The Rochefort surgeons will not be able to sustain the momentum after the midwife leaves, for the local girls refuse to study a matter so private with men.[14] When du Coudray is invited back in 1776 and again in 1781, she resents the fact that her impact here has been so fleeting, through no fault of her own, and attributes the scant success of her activities to the mediocrity of her successors. This is a "a source of annoyance" to du Coudray, and she declines to squander more time where there has been little serious effort at follow-through.[15]

For now, however, she basks in the glow of this hearty fan letter and in the impression, in this case illusory as it turns out, that she has once again left an indelible mark. How wonderful to have the king's royal surgeons gathered around her, hanging on her every word, virtually eating out of her hand. The hostility of surgeons has caused her a good deal of trouble elsewhere. Twenty-one years ago in Paris, when she agitated for instruction and signed the petition,

surgeons had come close to undermining altogether the practice of midwifery in the capital. They continue to stifle her former colleagues back in Paris even now. How far away that must seem! And how different things are for du Coudray, at least for the moment. It is something to savor.

24—

Brevet No. 2: The Royal Treasury:

Compiègne, 18 August 1767

Today, the King being in Compiègne, His Majesty, always occupied with the care of procuring for his people the help they need, principally with everything that can tend to their conservation, and well informed of the science and experience that said Dame du Coudray, midwife, has acquired in the art of delivery; wanting, besides, to repay her for the infinite attention she has taken to carry this so useful and so necessary art to a high degree of perfection, His Majesty has appointed her to teach the Art of Midwifery throughout the whole extent of the Realm. In order to obtain for her the means to transport herself . . . His Majesty wants and ordains that, as long as she gives public courses of instruction anywhere in the realm, she enjoy, each year, the sum of 8,000 livres that he accords her as annual gratification; and when age or infirmities no longer permit her to give said courses, [the sum] of 3,000 livres only, to facilitate her life in her retirement. Which sums will be paid to her . . . in future, each year, for her entire life, by the custodians of the Royal Treasury . . . starting this day.[1]

Finally, the coveted royal pension! No more talk of du Coudray needing to prove herself every year, as Ormesson had insisted. No more pipe dreams of the provinces pooling their respective monies, as Laverdy had originally wished. Now the king, while alighting at yet another of his palaces, has committed himself to a steady payment.

For the midwife it is a sort of epiphany. There was no way to enforce Laverdy's initial plan, to make the different regions contribute, especially in the climate of hostility to royal directives that had prevailed before Louis's scourging. The états of Brittany, where resistance to Versailles was greatest, flatly refused in early 1765 to pay the 270 livres "required" of each province, just as Le Bret had predicted. So did many others.[2] But things have changed since the king reasserted himself. The états and parlements had wanted a reduction

in the number of pensions paid by the Royal Treasury. Defying their wishes, Louis now adds another pension to the list, one supporting his ambassadress of birthing. Her mission is far too important to entrust to the regions, whose position on fiscal matters is historically intractable. From this day forward the central administration will guarantee du Coudray's salary. Laverdy, perhaps to compensate for the failure of his original plan and any anxiety caused thereby, has even arranged for a sum to be paid her in her retirement, a wonderful surprise.

She feels tremendously appreciated, and her expectations soar. Financial security at last! Or so one would think from this proclamation. Around this time she begins to make more grandiose plans. She will soon sit for her magisterial portrait, which, copied as an engraving, will decorate a new edition of her book. She is rejoicing, enjoying a buoyant sense of her new marketability.

But such happy tidings can make a person too prideful for her own good.

25—

The Bien(s) de l'Humanité:

Montargis, 30 September 1767

Orléans, Blois, Chartres, Montargis—the last eight months have been a flurry of activity in a particularly lovely part of the country. The intendant of this region, M. de Cypierre, has been following du Coudray's travels with interest since 1763,[1] but it took a while for him to placate the surgeons and persuade them that their corporate rights would not be undermined by a visit from her.[2] Now she has come with her growing entourage. Ample furnished lodgings have been found for her whole staff and their paraphernalia, "four or five persons and much equipment."[3] She is teaching one hundred women, the biggest group so far. It is a veritable performance, and the midwife relishes the attention. Her much-heralded entrance into the town and the arrival of her barefoot pupils streaming from the surrounding villages is merely the curtain raiser. The all-day lessons and demonstrations are a spectacle in their own right, culminating in the ceremonious granting of the royal certificates. The dismantling and packing up of anatomical posters and mannequins resembles the striking of a set as each engagement ends and she departs with her supporting cast of assistants for the next booking.

Today du Coudray is busily arranging her next trip, to Bourges. Over three weeks ago she committed herself to going there, name-dropping to the intendant, in a curious postscript, a reminder of her connections: "dear Frère Côme asks me to present to you his respects."[4] Evidently she anticipates trouble and believes this extra mention of the famous medical monk's patronage might be required to enhance her prestige there. Now she goes into more detail on her situation and her needs, in particular that whatever teaching space is secured for her be close to her residence.[5] She will require an "apartment nearby, that consists of several rooms furnished with four master's beds and one servant's bed. If it is possible to find in the house where I live a big hall where I could give my lessons, that would be convenient for me, but if all cannot be found together, I will give them at the Hôtel de Ville. The house must contain complete kitchen utensils, table linen, sheets, and the city provides wood. My salary is 300 livres each month. . . . The King has just accorded me an 8,000-livre stipend and 3,000-livre retirement pension [for] when my strength no longer permits me to continue the good of humanity. This last grace, which I had not expected, is a very particular kindness from the Controller General. I am very moved by it. I am not exactly sure when this salary will begin, so I cannot yet promise to go to Bourges at my own expense."

This money, in other words, is to cover her transport only. Stressing again that the city must in any case continue to pay the cost of her lodgings, she had asked for an advance for the travel, which she will reimburse as soon as the Royal Treasury pays her. She has been waiting nearly a month and now wants a go-ahead from the intendant immediately, "in order that I don't lose time so dear to the unfortunate and whose great value you know." She hopes to get to Bourges by 1 November, the holiday of Toussaint, for she needs two weeks to get settled before beginning her "operations and to put in order my machines, which are always disturbed by transport." In closing she pushes more, pressuring for an instant answer. It seems she has finally relented on the Bordeaux matter and might actually consider going there instead, hence the urgency of her tone. "If you cannot find the possibility of setting up this institution this year, if circumstances oppose your charitable desires for your province, I will accept the invitation from the intendant of Bordeaux, whom I asked to wait while I give you preference. The long trip [to Bordeaux] would become very disagreeable for me at

the beginning of winter, especially for my health, which doesn't adjust at all. You will forgive me this indulgence, but I am unfortunately forced."

So du Coudray, fifty-two years old, is now beginning to admit the strain, to economize a bit with her energy, to reveal how much she expends her own strength for her calling. She has never said things like that. Was de Blossac right when he predicted two years ago that she would soon begin to wind down? Of course, it is entirely reasonable that she try to avoid unnecessary detours whenever possible, particularly now that she needs to pay for her own travel. Why swoop down south only to have to come north again so soon? She must carry on with "the good of humanity," a phrase now found in all her letters—but at a price. Her work is "dear," of "great value," she reminds the intendant of Bourges in the same breath that she discusses her salary, conflating as she is increasingly wont to do the moral and monetary worth of the good(s) she disseminates.[6] She is manipulative in other ways as well, playing two invitations off each other and thus creating a sense of lively competition over her services, until she gets the desired result and heads for her chosen destination.

Somehow, however, in her eagerness to flaunt the new brevet with its generous provisions, to broadcast this latest vote of confidence from her monarch, she has boasted overmuch and confused some officials into believing they need provide for her nothing but a classroom. Having bragged too loudly about royal liberality, she now will have to spend much time and effort disabusing various regional administrators of the false impression that she comes entirely for free.

26—

The Students—"Mes Femmes":

Bourges, All Saints' Day 1767

The midwife targeted this holiday of Toussaint for her arrival here, and Bourges with its huge dark cathedral is bustling. Nearby in the Voiselle Marshes "water rats" (market gardeners) get about in flat-bottom boats. Here, and at other local fairs throughout France today, women sell surplus dairy products and sometimes a fattened cow that would do poorly on the sparse fodder (at best some marsh

grass) available in winter. A new cow can be purchased in the spring. Such activities are part of the rhythm of the peasants' year.