Three—

The Inquisition's Repression of Curanderos

Noemí Quezada

As an ethnologist, I have focused my interest on the curanderos, or folk healers, of colonial Mexico in order to explain both their persistence and their continuity in medical practice. I also wish to define the role of the curanderos and to examine their importance within this evolutionary social process, for the curanderos' knowledge and skills contributed to the health of the oppressed and led to the formation of a traditional mestizo medicine that syncretized Indian, black, and Spanish folk medicines. These categories of analysis confirm the important social function of traditional medicine and its practitioners who offered a solution to the health problems of the majority of the population of colonial Mexico.

The necessary existence and function of the curanderos in New Spain can be attributed to the scarcity of doctors.[1] The authorities allowed for their presence and practice with a degree of tolerance that came to characterize the prevailing social relations in the American colonies, allowing not only for the continuity of traditionalist medicine but also for the beliefs and practices of the ancient pre-Hispanic religions as a means of resistance.[2]

The Crown was politically conscientious in establishing a legal medical system for Spaniards, thus protecting the health of the group in power. The Indians, and eventually the blacks and mixed castes, were assigned the practices of the curandero. Yet this division along class lines went ignored; Spaniards frequented the curandero as much as the other groups. Given its social dynamics, traditional medicine permeated the entire New Spanish society.[3]

If the curanderos were necessary, then why were they pursued, tried,

and punished by the Holy Office of the Inquisition? The contradiction presents itself in ideological terms: on the one hand, their services were required as experts on the human body, as able surgeons, and as superior herbalists; on the other hand, they were harshly repressed for the magical part of their treatment, which frequently contained hallucinogens and which the authorities, according to the Western world view of the time, viewed as superstitious.[4] The authorities intended to prove that medical expertise derived solely from Spanish medical knowledge; they would thus invalidate the entire medical practice of all other practitioners and justify their condemnation.

The Curanderos and the Holy Office[5]

From the very beginning of the conquest of New Spain, the Spanish Crown attempted to impose a Catholic world view upon which to base a system of normative practices that would organize the entire society within the framework of religion. The problems presented by the social and ideological heterogeneity of New Spain were extremely difficult to solve. The colony's reorganization was carried out along administrative, economic, and political lines, but resulted in a different dynamic on religious and cultural levels. The goal was to unify the entire society under the Catholic faith, which in actual practice was interpreted and molded according to each social group's conception. Despite the Church's efforts to disseminate its official doctrine through regular and secular clergy with the support of the civil authorities, the various social groups—mixed castes, Indians, and marginalized Spaniards—perceived Catholicism as an ideal impossible to live up to on a daily basis. Thus, the religious beliefs of New Spain reveal a process of syncretism reflecting popular religion and culture.

At times even unconsciously, civil and religious authorities strove to achieve their assigned goal of social integration; unity, however, was at best superficial in a society where diverse ideologies coexisted and interrelated, ultimately resulting in a less strict and orthodox situation than in Spain.[6] The unification of Spanish society under the reign of the Catholic monarchs, as well as the Church's gradual loss of political power as it increasingly came under monarchical control, had repercussions in the American colonies, where the lack of jurisdictional limits over control and conservation of the faith led to frequent confrontations between civil and religious authorities. To maintain order and to ensure the system's equilibrium, constant vigilance was needed via the institution created in Europe in the thirteenth century and adopted by the Catholic

kings at the end of the fifteenth century:[7] the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, which functioned as a disciplinary apparatus, "an organism of internal security,"[8] controlling dissidents within the religious, moral, and social order.

The first missionary friars were invested with the powers of the secular clergy where there was no priest or bishop, and they were responsible, among their other duties, for the detection and punishment of all violations of the faith.[9] No case of curanderismo appears registered under the first commissioners of the Holy Office.

Fray Juan de Zumárraga, the first bishop of New Spain, received inquisitorial powers in 1535, and he established the episcopal inquisition with a tribunal and inquisitorial functionaries in 1536. Under his supervision, which lasted until 1543, twenty-three cases of witchcraft and superstition were tried, probably including some cases of traditional medical practices.[10]

Petitions first circulating in the middle of the fifteenth century explained the need to establish a Tribunal of the Holy Office which, like that in Spain, would have total disciplinary control, thus avoiding the frequent abuses and jurisdictional equivocations of the civil authorities. Philip II authorized the tribunal in 1569 with royal letters-patent, and it was established in New Spain in November, 1571. As in Spain, the New Spanish inquisitors were, above all else, men of law who scrupulously carried out their duties in order to maintain social control.[11]

After Zumárraga had condemned the cacique of Texcoco to the stake for idolatry in 1539, causing him to be removed as inquisitor, the question arose as to whether the Indians should suffer inquisitorial penalties since the Crown was legally responsible for their guardianship and protection.[12] Fully aware of the abuses committed by the provincial commissioners supervised by the bishops during the episcopal inquisition, Philip II decided to leave the Indians outside the control of the Holy Office and placed them under the ordinary jurisdiction of the bishops.

Although the royal decision was respected, inquisitorial commissioners did receive accusations against the Indians. For some of these commissioners the separation of jurisdictions was quite clear;[13] for others, confusion, jealousy, or the belief that the crime merited inquisitorial punishment incited them to apprehend, reprimand, and threaten the Indian curanderos.[14] Once the denunciation was issued, it was important to determine whether it concerned "pure Indians" or mestizos; to remove all doubts, the Holy Office thus required that the commissioners formalize the proceedings with documents such as testimonies.[15]

Of the thirteen cases concerning Indians found among the proceed-

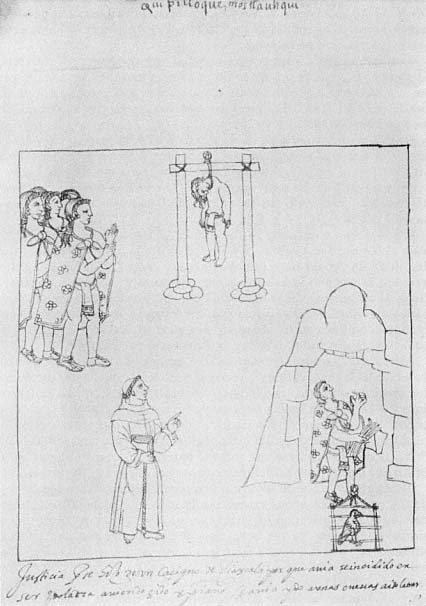

Fig. 5.

"Punishment of a cacique of Tlaxcala for falling into idolatry after becoming a Christian."

ings I have examined, that of Roque de los Santos, who was accused as a mestizo, appears to be illegal. During the course of the trial, it was discovered that he was an Indian; nonetheless, he was sentenced, and it remains unclear whether sentencing occurred because he was part of the same trial as Manuela Rivera, "La Lucera," or because the inquisitors decided that the punishment was appropriate for a mestizo. Proof of this racial status was furnished in a document not included in the proceedings. He was sentenced to be paraded in a cart preceded by a town crier who announced his crimes, to receive two hundred lashes, and to labor eight years in a mining hacienda.[16]

The Curanderos Punished by the Holy Office

Of the seventy-one delations and denunciations which the Holy Office received against curanderos, fourteen warranted attestations and were dismissed after being considered inappropriate. Twenty-two cases were tried which called for testimony; in fourteen cases the inquisitors decided in favor of public or private reprimand, two suffered public humiliation, only one had a public auto de fe in the Church of Santo Domingo, and one was exiled. These were the maximum punishments suffered by the curanderos.

The first cases specifically recorded in the registers of the Inquisition as offenses of curanderos were those of Francisco Moreno, a thirty-year-old Spaniard accused of healing by incantation in 1613, and the mulatta Magdalena, for having taken peyote as a divinatory aid.[17]

From this time until the beginning of the nineteenth century, the accusations against the superstitious curanderos give descriptions of the therapies that identified specializations and the use of herbs and hallucinogens in the curative ceremonies. Most importantly, they attempted to understand the practitioners of traditional medicine and their patients, disclosing the latter's reactions and fears regarding the unknown, the mysterious ways of those who dealt with their health, and patients' belief in their powerful supernatural faculties.[18]

It was also a common belief that bewitchment and all incurable illnesses resulted from hatred or unrequited love. Between these two poles revolved the relationships of New Spanish men and women; seeking good health, they appealed to the curanderos, yet when undergoing treatment, sometimes positive and other times negative, they often fell into the contradictory position of thinking they had violated the norms imposed by the Holy Office. This reaction, quite natural for the times, accounted for the detailed records of the inquisitors which have fur-

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

nished us with all the cultural data needed to confirm the continuity of curanderismo within medical practice, to determine its changes, and to specify the concepts and judgment of that medical practice, formed, on one side, by the curanderos defending their practices and, on the other side, by the inquisitorial authorities who wished to repress them.[19]

The Accusations

Self-accusations were unusual, perhaps because the curanderos did not consider their practice a crime. Only Francisco Moreno and Mariana Adad denounced themselves. The former found out in an Edict of Faith that the occupation of spell-caster (ensalmador ), which he had practiced for many years in various cities in New Spain, was prohibited; presenting himself before the inquisitorial commissioner of Oaxaca, he sought clemency through his open declaration of ignorance. In her report, Mariana minutely describes her case, from predestination since infancy through her initiation and practice; she was confident that the inquisitors would assess her healings as a gift from God.[20]

Delation was the most frequent reason for detention given in the reports, and it is not surprising to discover that the majority of the delators were the former patients of the accused curanderos. On occasion, knowledge of an edict that had been posted on the doors of the church and had been read by the priests during mass on Sundays or holy days aroused unrest and fright, unleashing in turn a series of accusations made by the informers "in order to relieve the conscience."[21]

When the informer presented him- or herself before the inquisitors at the Holy Office in Mexico City, the provincial commissioner or priest with inquisitorial authority swore to keep the secret. The informer was asked what type of declaration he or she was prepared to make, since the kind of process depended upon whether it was merely a delation or an actual accusation. The prosecutor of the Holy Office made the accusation after hearing the attestations and presenting the case before the qualifying judges.

In spite of the declaratory oath, it is probable that the actual reasons for a delation were hatred or resentment when the cure had negative results, at times worsening the patient's condition, or when the curandero had refused to attend a sick person.[22] In those cases where the remedy had positive results, the patients, having disobeyed the faith by resorting to forbidden practices and specialists, sought to lighten the punishment they believed they deserved by accusing someone else. Neither family nor romantic ties were exempt in these circumstances.

Feelings of impotence in the face of illness, fear of the unknown, envy, competition, and fear inspired by love, all impelled New Spaniards to the Holy Office.[23]

Delations presented through public rumor were received and investigated. Between one and four attestations were sufficient to ensure continuation of a case. In some cases, the curanderos' public reputation became an issue with the priests or civil authorities, as it caused a public disturbance and loss of control over the faithful; the priests then had the responsibility of making the accusation to the Holy Office.[24]

When provincial commissioners or priests with inquisitorial authority were involved, they usually sent the complete delations and reports to the commissioners of the Holy Office beforehand, so that upon receiving a response from the qualifying judges they would know how to proceed with each case.[25] Inquisitors were responsible for the most stringent enforcement of the rules and regulations of the Holy Tribunal. They often expedited the Instructions to ensure the correct methods of inquiry and to obtain greater information in order to standardize judgment by the qualifying judges, thus avoiding, wherever possible, errors that might discredit the prestige and deplete the treasury of the Holy Office.[26] There were few cases where the accused could not be located, either because too much time had transpired between the crime and the accusation, or because he or she had died.[27]

The Trials

Once the delation or report was received and the trial subsequently endorsed, the first step was to call upon the witnesses, dismissing those cases where interrogation revealed that they had been motivated by hatred, desire to defame, or other similar reasons. Witnesses presented by the informer or called by the commissioner were advised of their responsibility and the importance of their testimony, as well as of the punishment incurred if their testimony should prove false or motivated by hatred or enmity. In accord with the rules, witnesses were assured of and sworn to secrecy.[28]

The purpose was to gather as much information as possible in order to continue the trial or to dismiss it. Although the number of witnesses in the cases of curanderos varied depending upon the offense committed, it was usually determined by the conscientiousness of the commissioner. For example, more than twenty witnesses were called in the trial of María Tiburcia, while eleven were called in the trial of Manuela Josefa; in general, the average number was four or five witnesses. In the

case of Petra Narcisa, six testimonies were presented, and since the information was considered insufficient to decide the case, the trial was rescheduled and six other witnesses were called in order to define the charges.[29] Moreover, it was common to request testimony from the curanderos' former patients, relatives, or assistants.[30]

Detentions and Imprisonment

The judges ruled whether or not to proceed with the trial on the basis of the testimonies, with the prosecutor of the Holy Office presenting the formal accusation.[31] Once the decision to proceed had been made, the accused was detained and placed either in the secret jails of the Holy Office, in the curate jail, or in the royal jails; in some cases, women were taken to houses of correction.[32] The goal was to interrogate the accused as many times as necessary.

When the prisoner was placed in the jail of the Holy Office, a very meticulous physical description was made, along with a description of all articles of clothing, other personal belongings, and bed clothes.[33] In six cases the prisoners' belongings were confiscated, and in only one was it noted that they were "few and poor." The other five cases make no mention of the value, from which we can infer that the total was unimportant. Transfer of prisoners from the interior of New Spain to the jails of the Holy Office in Mexico City was done infrequently, since the expense was covered by the prisoner's own possessions. Where there were no possessions, the tribunal covered the expense, ordering a careful examination of "the quality of the person and the nature of the offense, and the trial to take place only under great consideration."[34]

There were anomalies in the detentions; for example, when Miguel Antonio and his wife presented themselves to denounce Manuel José de Moctezuma, all three were imprisoned. The curandero was set free, but the denouncers were detained for an additional period of three days and received a sharp reprimand for having taken pipiltzintzin , a hallucinogen recommended by Manuel José.[35] Priests who made arrests without the authorization of the Holy Office were also severely reprimanded, and if the civil authorities tried to make arrests, the inquisitors protested the encroachment on their jurisdiction.[36]

The length of time in prison varied with the duration of the trial; in general, it fluctuated between the three and five years it took to complete the trial. Only the prison cells of the Holy Office were safe and adequately guarded; in other locations the prisoners were able to escape. One curandera did so by burning down the door; although she was able

to escape, she was captured because she was very ill. "El Churumbelo" escaped through the rafters of the jail ceiling, but he was captured and returned to prison. María Margarita, with the help of her daughter, escaped in shackles. Among the fugitives was José de Roxas, arrested for teaching forbidden prayers to children; he was the only fugitive who was never captured.[37]

The Confession and Torture

The interrogations of the curanderos proceeded in the usual way. In general, they accepted the charges and confessed correspondingly; only Agustina Rangel denied the eighty charges imputed to her. "La Cirujana," feigning insanity and sickness with hallucinations of snakes, almost managed to deceive the inquisitors and avoid indictment.[38] The interrogations provided proof complementing the accusations against the prisoners. For example, Lorenza, an elderly midwife, never "wished to declare the kinds of herbs" that she used in her healings. In these cases, specialists were sought to identify the medicinal plants in order to determine if they were prohibited.[39]

All of the punitive rules and regulations of the Holy Office were based on physical punishment: not only torture but deprivation of liberty, imprisonment in dark, humid cells, solitary confinement, whipping, and even the public exhibition of the prisoners in specific clothing and the parading of male and female prisoners naked to the waist were all degradations not easily forgotten by the individual or society. That was, after all, the objective: to conserve a vivid memory of the punishment.

In two cases of curanderos, both were tortured in order to obtain confessions: José Quinerio Cisneros, a mulatto whose file contains the decree that torture be applied, because of his reluctance, "one or more times, as much as is necessary,"[40] and Agustina Rangel, aware of the inquisitorial mechanisms, who declared that she thought she was pregnant, since she "finds herself with great pain in the belly and hips." This excuse most probably postponed both trial and torture.[41] Despite the torture, Agustina continued to deny the eighty charges pressed by the prosecutor, repeating before the inquisitors if she had cured people, it was by "the grace of God and of the Holy Virgin and Santa Rosa," who helped and advised her, Santa Rosa entering her body to cure the sick. The qualifying judges were the ones who asked the prosecutor to torture her, to see if she would confess the truth.[42] Convinced of her revelations, she insisted on denying the charges even after torture. When she was sentenced in October 1687, two years after she had

been detained, she again denied the charges. Not until February 1688, when the sentence was carried out, did she admit to them.[43]

The Sentences

The most frequent punishment against the curanderos was a reprimand with a prohibition against their practices. In most cases, the reprimand took place privately before the commissioner, the notary, the prosecutor, and the inquisitorial witnesses, gathered together at the trial's final hearing when it took place in Mexico City. In other places, it was made before the representatives of the Holy Office. Public reprimand was carried out by the same officials with six, eight, or more witnesses.[44]

The reprimand was meant to be a lesson to the accused, and the justification was that in many cases no other punishment was applicable, since "because of their backwardness they cannot be charged with any heretical intention," or because they had committed the offenses "without malice, only in order to avoid working and to swindle innocent people."[45] The reprimand was severe and its threat was important. The tribunal took harsh measure against recidivists. After the reprimand, the prisoners would make an oath promising not to repeat the offense. Juan Luis, a black man, was warned he would receive public reprimand of twenty-five lashes at the church door if he did not honor his oath.[46] "La Cirujana" was a recidivist, who, because of her illness, did not receive any major punishment and was placed in a convent.[47] Moreover, reprimands were issued against ignorant witnesses and denouncers.[48]

Public Punishment

Public punishment functioned as an educational ritual of inquisitorial power. The principal assumption was that exemplary punishment would prevent New Spaniards from committing offenses. Francisco Peña is emphatic about the concept of punishment: "The primary objective of the trial and death sentence is not to save the soul of the accused but rather to procure public welfare and to terrify the populace."[49]

The penitents, carrying candles, gagged, and wearing tunics, coneshaped hats, and nooses, covered with symbols indicating their offenses, were exhibited publicly, their crimes published and repeated by the town crier. The prisoner was thus penalized not only by inquisitorial authority but by the entire society as well, represented by those participating in the ritual. People who attended the ritual liberated themselves

through self-expression in the ceremony, and they learned from the punishments not to commit the same offenses. They saw the penitents' sufferings in these rituals that catalyzed the repressive New Spanish society. The goal of publishing the penalties was to avoid social transgression, disequilibrium, and rupture.

Few curanderos received these punishments. Two women suffered public humiliation. Manuela "La Lucera," after a long imprisonment of five years, was paraded in 1734 through the customary streets by a crier who finally gave her twenty-five lashes at the pillory; the second part of her sentence consisted of working in a hospital for six months.[50] "La Salvatierreña," a forty-six-year-old free mulatta, was led through the streets by a crier promulgating her offense and received twenty-five lashes at the pillory; she was sentenced to prison and severely reprimanded, being required for one year thereafter to make her confession at the main altar, and to pray three Salve Reginas and three Apostles' Creeds after mass.[51]

The maximum penalty for the curanderos was the abjuration de levi , a formal oath to avoid this sin in the future. The only one who received it was Agustina Rangel. Before it was carried out, she embraced Christianity and accepted the accusation made against her. The abjuration took place in the church of Santo Domingo on 8 February 1688. At the end of mass, she offered a votive candle to the priest and performed the abjuration in expiation of her sins. The following day, 9 February, she was "taken on a beast of burden, naked to the waist, wearing the aforementioned noose, and cone-shaped hat, and led through the customary streets," with the crier announcing her offenses as he led the way to the pillory where she received two hundred lashes. On 12 February she entered the Hospital of the Conception of Jesus of Nazareth to serve the poor for a period of two years. Her file states that she served the entire sentence, obtaining her liberty in February 1690.[52]

José Antonio Hernández, a Spaniard whose case required ten witnesses and whose trial lasted four years, was kept prisoner by order of the board of royal physicians who charged him with being a curandero and an herbalist. The qualifying judges finally found him to be "a suspect de levi against the Holy Catholic Faith," but there is no definitive sentence.[53]

Finally, José Quinerio Cisneros, accused of being a superstitious curandero, received the following sentence: exile from the towns of Madrid, Mexico, and Salamanca for "a period of ten years, during which the first two are to be spent in the Castillo de San Juan de Ulúa, assigned

to royal tasks, on prebend and without salary." After one month in San Juan, he made his confession, and did so also at Easter. Every Saturday he offered part of the rosary to the Virgin Mary.[54]

Conclusions

The beliefs, practices, and behavior of the curanderos punished by the Holy Tribunal were as follows:

1. The belief that they should not infringe upon established religious norms. They were convinced that they should heal the sick through their therapeutic techniques and with the aid of supernatural beings, whether originating in Catholicism or in other religions.

2. The use of hallucinogens that served not only as medication but also as a means of achieving a magic trance, consciously seeking auditory and visual hallucinations that would allow them to establish contact with supernatural beings.

3. The presence of prayers, images, and sacred and at times consecrated relics in the curative ceremonies.

4. Divination as a means of making both diagnosis and prognosis.

New Spain's classist society, with its heterogeneous culture, included several conceptions and practices of the curanderos. While Spanish curanderos argued that they healed people "through the grace of God," the mestizos, mulattoes, Indians, and blacks followed a traditional method based on their teachings and practices. The supernatural beings invoked in the curative ceremonies correspond to the world view of each group. For the Spaniards they were the Catholic deities: Jesus Christ, the Virgin, the Holy Trinity, the Holy Spirit, various saints, and the Devil. They cured with their dialogues, revelations, and even through bodily possession, but always within the framework of individual healing. The other groups however, while acknowledging and invoking Catholic deities, fundamentally perceived pre-Hispanic deities in the hallucinatory episodes; and while these divinities aided, directed, and prescribed, it was the curandero who healed, involving both the patient and the assistants in a collective healing.

The curanderos appeared as transgressors of established morality, since they were said to have participated in condemned practices such as concubinage, homosexuality, and promiscuity. Yet the vast majority of the curanderos were exempt from punishment, as their herbal medicine did not merit any type of condemnation, and they were eventually

permitted the use of officially sanctioned images and relics. The Holy Office's response confirms that the medical practice of the curanderos was viewed and accepted as a necessity. It was within reach of the general populace; the curanderos were as poor as their patients, since in the confiscation of personal belongings, no curandero with money was ever found. The colonial curandero thus served a specific function by offering a solution to the health problems of most of New Spain through the use of an efficient traditional medicine.