4. A Son of Safi

I will tell you the story of the Khalqis. It’s interesting. When the Khalqi coup d’état occurred, [I was with] a guy by the name of Habib who worked with me at the journal Erfan. He was a Khalqi of the first degree, but he didn’t know what was happening. A person would think that they had just captured some thief or something. There were some gunshots coming from in front of the presidential palace [arg-i jumhuri], but not a lot. It didn’t seem important. We were close by, so we went to see what the firing was all about. Then we realized that it must be a coup d’état or some other matter.

We went from there, and finally we discovered that it was a coup d’état. While the coup d’état was going on, everyone left work, and I climbed up the shoulder of Asmai Mountain and saw that the presidential palace was under bombardment. It all really happened while I was sitting there. The airplanes weren’t using explosive bombs. They were engaged in tactical maneuvers over the palace, not destructive bombing. It was late afternoon, Thursday.

I was happy about this, that the airplanes were maneuvering over the palace and attacking. I was happy. I don’t know if it was conscious or unconscious, but I was happy. I went from there to the house. When I came in the house, I was still happy, and I told my wife, “Something very good has happened.” I told her how I had seen the bombardment of the palace with my own eyes. I wasn’t able to see the people who would flee, the oppression that would come upon them, and everything else. I didn’t see all of this when I was looking at the palace, but when I saw all of [the airplanes] overhead, I became happy. I was happy.

The radio went, “Dong, dong, dong, dong.” It’s the late afternoon, and all of a sudden, for the first time, [Aslam] Watanjar is speaking. I didn’t recognize his voice. There’s a shop nearby, and occasionally, in the late afternoon, Watanjar and I would sit and chat, but I knew him only as “Jaghlan Saheb,” not as Watanjar. He would sit and wrap a turban on his head. He would rarely come dressed in his military clothes. It was a shop on the biggest street in Kabul. It was a pharmacy. The owner of the shop, who was named Wali, was martyred later on in the uprising in Chandawal. He was a very manly person. I would never have foreseen that. He fought well and was martyred.

This man, his voice came on, but I didn’t recognize it. Right after that came the voice of Hafizullah Amin. Since I had known him from long ago, I was acquainted with his voice, and earlier I had heard that they [the Khalq party leadership] had been arrested and were in prison. Therefore, I realized that since it was he, this coup d’état must be a Marxist coup d’état.

I had a cigarette in my hand. I threw the cigarette in the ashtray like this. I let out a sigh and stretched back in the chair.

My wife said to me, “Up until now, you’ve been happy. What’s wrong?”

I told my wife, “Until today, I was the father to my children, and you were their mother. After today, from this minute, you are both their father and their mother.”

“Why?”

I said, “The Russians have taken our homeland. The Marxists have come to power.”

My wife said to me—she was trying to understand what I meant—“It’s Hafizullah Amin’s voice?”

I said, “Yes.”

She said, “He’s your professor and also the friend of your father and your personal friend. So why?”

I said, “This isn’t a personal matter or a question of friendship. He’s the servant of Russia, and as far as our friendship is concerned, how was I to know he’d take power? Our relationship was personal, but no one would approve of his taking power into his own hands. By whatever name they call themselves, the people of Afghanistan don’t want foreigners, and these are the servants of Russia.”[1]

The success of the Marxist coup on April 27, 1978, initiated a struggle in Afghanistan that continues to this day. For Samiullah Safi, the struggle was not simply about ideology and political control. It was also intimately tied up with his personal and family histories. Like other educated Afghans of his age and status, Samiullah, who is known to all as “Wakil” (representative) for his years spent as a parliamentary deputy, [2] was acquainted with many of the principals in Afghanistan’s political struggle, from the former king, Zahir Shah, to leaders of dissident political parties, including the Marxist Khalq party, which succeeded in taking power in the Saur Revolution of April 1978. The single figure whose story was most intimately bound up with Wakil’s own, however, was probably President Muhammad Daud himself, who was engaged in an ultimately futile gunfight with rebel officers in the inner chambers of the presidential palace at the very moment that Wakil was watching the aerial maneuvers of rebel air force officers from the heights of Asmai Mountain. Daud’s involvement with the family had begun thirty years earlier, when the Safi tribe had risen up against the government and then General Muhammad Daud had been dispatched to end the hostilities. When Wakil saw the palace of Daud under siege, he had reason to rejoice since this same man had been responsible for exiling his entire family far from their home in the Pech Valley in eastern Kunar Province to the western part of Afghanistan.

Wakil himself was a child of four or five when these events occurred, but he remembered some of them well. They were the formative events of his youth, and so when he talked of his initial happiness while watching the bombing of the presidential palace, he was speaking indirectly of this enmity and his family’s troubles, and his happiness was directly connected to the grief then being inflicted on his family’s old adversary. But Wakil’s euphoria was short-lived. He had only to hear the voice of Hafizullah Amin, the chief planner of the coup d’état and number two man in the Khalq party, announcing the destruction of Daud’s government over the radio to know that he could not remain inactive.

As Wakil’s wife indicates, Amin was a close acquaintance of Wakil’s. Amin had been his teacher in secondary school and then the principal of the teachers’ college he attended as a young man. They had stayed in touch over the years, and Wakil certainly knew about Amin’s involvement in Marxist politics. In Afghanistan, however, the only politics that mattered much in the half century prior to the Marxist coup were the politics internal to the royal family and the retinue of ministers and retainers that surrounded that family. But all of this had begun to change in 1973, when Daud had overthrown the king and dismissed the parliament. The Khalqis, along with their bitter Islamic rivals, had gone underground, and their activities had become more secretive and ambitious. The openly incendiary politics of parliamentary debate had been replaced by a covert politics of recruitment, organization, and plotting. Behind the scenes, as Afghans were well aware, was the specter of the Soviet Union, waiting its opportunity to place its own puppet rulers in power and make Afghanistan an extension of its own domain.

That was the common perception, and Wakil’s reported response to the radio announcement reflects this perception. But Wakil’s dramatic pronouncement to his wife that henceforth she must be both mother and father to their children has a deeper resonance as well that relates specifically to Wakil’s family history, part of which I recounted in Heroes of the Age. In that book, I transcribed verbatim a story told to me by Wakil concerning his father’s coming of age. Wakil’s father, Sultan Muhammad Khan, was a well-known tribal chieftain (khan) from the Safi tribe of Pech Valley, and part of his renown stems from this story—which begins with the murder of Sultan Muhammad’s father by political rivals whose lands adjoined his own. At the time of the murder, Sultan Muhammad was a young boy and had few paternal kinsmen to support him in the conflict, which was driven by the family’s considerable wealth but relative lack of male kinsmen who could help in defending the family’s lands and properties. In this situation, Sultan Muhammad was forced to leave his home and take refuge with a local potentate, the Nawab of Dir in present-day Pakistan, in whose court he became a respected scribe. But Sultan Muhammad knew that a day of reckoning would have to come. To accept the diminished status of a court scribe meant also turning his back on his tribal inheritance. So he returned and bided his time, waiting for his rivals to strike at him but knowing that he would have to strike first. The opportunity came when his rivals had become so brazen and sure of their own power that they accepted an invitation to meet in his guesthouse to discuss the terms by which Sultan Muhammad would turn over a portion of his family’s disputed lands to them. Sultan Muhammad, in league with a handful of kinsmen and tenant farmers, ambushed his rivals while they sat in his guesthouse, killing all seven of the brothers who had been responsible for his father’s death.

The story of Sultan Muhammad’s revenge told in its entirety is complex and primordial, and it was an important part of Wakil’s legacy. Even more than Taraki, he was a “child of history,” the son of a legendary figure whose life was dedicated to the unrelenting pursuit of honor. Sultan Muhammad’s life story demonstrates that the pursuit of honor, once embarked on, can never be abandoned; nor can the goal ever be achieved. Wakil inherited not only his father’s legacy, which would serve throughout his life as a goad and rebuke, but also the recognition that the pursuit of honor entailed costs and consequences for the individual and those around him. Wakil also grew up in a more complicated world than his father’s, a world where honor’s value was not so self-evident. Sultan Muhammad faced the choice between remaining in the relatively secure but socially debased position of a servant in the court of Dir or returning to the insecure, but more highly esteemed, role of a Safi tribesman—the son of a Safi father and the father of Safi sons. Wakil’s choices, as this chapter illustrates, were more varied. He could be many things, earn other laurels, and live in a variety of places inside Afghanistan and abroad. But always there was the specter of his father and his father’s commitment to honor and the recognition that in the land of his birth a man’s first obligation was to live up to the obligations that being a son of a renowned father entailed.

Wakil’s reported response to his wife on hearing the voice of Amin over the radio—whether it accurately reflects what happened or not—shows us the way that the past casts its shadow on the present and how some people at least gauged their response to the Marxist revolution in relation to traditional cultural understandings and modes of conduct. But also striking here is the extent to which traditional cultural understandings and modes of conduct didn’t apply. Afghans had never before faced a situation like this one, and their society was a good deal more heterogeneous than the one in which Sultan Muhammad and other remembered ancestors had made their fateful choices. The most straightforward of the changes impinging on Wakil’s life had to do with the division of the world into realms of tribe and state. In the past, tribes and states had interacted with and relied in various ways on one another, but the domains of tribe and state were governed by different moral understandings, and these differences were sustained by the continued existence of spatial separation and political autonomy. By the time Wakil came of age, however, such practical distinctions had blurred, as had many of the cultural underpinnings that someone like Sultan Muhammad could take for granted; the choices Wakil had to make were far more ambiguous in significance than any that had confronted his father. In the pages that follow, I chart the course of Wakil’s life history as revealed in his own words and stories and focus on what I take to be the pivotal moments when the moral logic of honor clashed with the exigencies of living in an increasingly modern and hybridized society.

In my discussion of Sultan Muhammad in Heroes of the Age, I was concerned with the distant past, and the vehicle by which I sought access to this realm was a family’s legends of an ancestor’s youthful deeds. In this discussion of Wakil’s life, I move into a more proximate realm of history and rely on another resource—the personal memory of the person whose life is thus narratively shaped and fashioned. The stories that he told me, while they aspire to consistency and completeness, are still fragmentary in places, inconsistent in others. The voice I listened to was by turns vainglorious and uncertain, abject and self-serving. As history goes, Wakil’s account is probably badly flawed, and I don’t doubt that if it were shown to others who were present at the events recounted, his version might be challenged at various points. All this is to be expected and goes with the territory of oral history. But Wakil’s tale has a complicating element beyond that of most oral histories because of the looming presence in the background of the heroic father, Sultan Muhammad Khan.

A great man casts a long shadow, and we can see in the stories that follow Wakil’s attempts to come to terms with his father’s legacy—in particular, to make his own deeds live up to his father’s, even though the opportunities that life afforded him were not congruent with those his father encountered and despite his having values that diverged in important respects from those of his father. Wakil spent most of his life outside the insular world of the tribe and the valley; he lived in various provinces far from the frontier and in the capital of Kabul, and he attended secondary school and university. His horizons were thus a good deal broader than his father. But still there was that shadow, and the glories, the travails, and the ironies of Wakil’s life history are all finally bound up in the difficulties of finding a place for honor in the modern world.

First Memories of War and Exile

I think the Safi War [safi jang] was in 1945. It continued for a year and stopped in the winter of 1946. The government secretly planted some paid spies among the people. Approximately five hundred families were exiled after the war. I remember. They brought lorries. I was still small, and I was very happy that I would see a new world. The adult men and some of the women were crying. This exile suddenly came upon our family. I was just small, and I heard that my father had come. He had been in prison along with my uncle. Just one of my uncles was at home. One of my brothers was at the military high school. People arrived—all of a sudden. We heard. One or two people said, “Look!” They were all wearing normal country clothes—not uniforms. I thought that people were coming, and it was announced that my father had been released from prison. My father would be back home with us the next day. I was happy. [It was as though] the Jeshen (Independence Day) celebrations had begun. I was very happy. They were all armed, and as soon as they had come, they suddenly captured my family. Two or three hundred people, all dressed in civilian clothes, all are with the government, they captured us and said, “In the morning, you will be leaving.” [3]

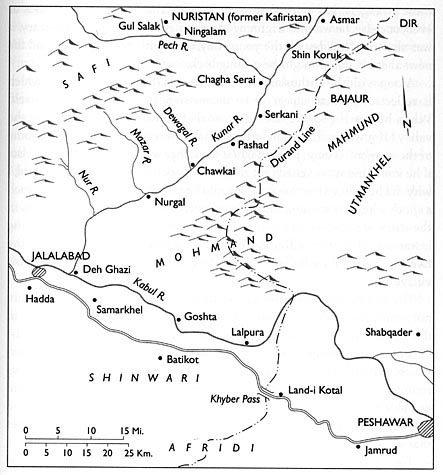

This is one of only two stories (fragments is perhaps a better term) that Wakil told me about his life in Kunar as a young boy, stories that are from his own memory (see Map 1). There are probably others, but not ones that he considered appropriate or significant enough to share. The impression I received when I talked with him, an impression that has been reinforced by hours of listening to the recordings of our interviews, is that Wakil’s remembered life begins on the day the troops came to take away his family. Stories told about earlier episodes, including those involving the Safi War itself, were all impersonal. They are not part of his story. They belong to others, and it was clear even when he did not say so that these were events he had heard about and did not witness himself. All of this changes, however, from this point on. From the time the troops arrive at his family’s home through ten more hours of interview, it is Wakil’s story that is being told, and that story often has a harrowing quality.

Map 1. Eastern Afganistan

In telling the story of the coming of troops to his village, Wakil’s voice became that of the small boy who witnessed the events described, and the story manages to convey the sense of enthusiasm that he must have experienced at the time as he watched the strangers arrive in his village. Were theirs the first motorized vehicles he had ever seen? There were many of these strangers, but since they were wearing the same sort of clothes as everyone else, he was not frightened by their appearance. To the contrary, it was all a great holiday for the young boy, what with all the activity and the news that his father might be coming back.

Along with the enthusiasm, one also senses the boy’s confusion, which is reflected in what appear to be inconsistencies in the narrative itself. When he saw the lorries, did he know that he would soon be leaving the valley? If it was such a happy occasion, why were “the adult men and some of the women” crying, particularly if his father would soon be home? Also, if he knew and was excited that they would soon be seeing “a new world,” why did he believe that his father would be returning, and why was it such a shock when the soldiers suddenly arrested his family? These elements in the story are unclear and cannot be easily resolved, but, instead of being instances of bad storytelling, perhaps they signify the bewilderment of the five-year-old child who has never before seen so many strangers in his village.

The story’s inconsistencies cannot be reduced to this however. They are not simply the product of childish distraction, for there are also indications in this shred of memory of deeper confusions in a society that was in the midst of conflict and change. The relatively cohesive and integrated world within which Sultan Muhammad came of age was not the world that Wakil was coming to experience. The pole star of honor by which Sultan Muhammad was able to chart his life choices would not shine so brightly for the son, and this first memory gives preliminary signs of the atmospheric disturbances that will cloud the boy’s course.

Thus, for example, we see soldiers wearing civilian clothes, and we hear of tribesmen (Wakil’s older brother among them) who are not present because they have already been sent off to boarding schools where, the government must have assumed, their interests would come into alignment with those of the state. The old divisions were breaking down. The worlds of the tribe and of the state had always been linked by the binary logic of their contrastive moral codes (tribes defining themselves by what they were not—the state—and vice versa). However, in this slight, but revealing vignette, the lines of distinction seem to have blurred. People were not who they appeared to be, and one sort of thing was easily mistaken for another, as when the young boy compares his (soon-to-be disabused) happiness at the excitement around him to the happiness he had previously felt during celebrations of Independence Day.

The event that led to Wakil’s exile from Pech, the so-called Safi Jang, followed almost two decades of relatively calm relations between the Pakhtun tribes and the Afghan state, the last major conflagration having been in 1929, when the Shinwari tribe of Ningrahar Province and various of the tribes of Paktia Province had spearheaded the insurrection that toppled the regime of King Amanullah. The single most significant factor in inciting the Safi tribe to battle was a government plan to change the rules by which it conscripted tribesmen into the army. [4] For many years prior to the uprising, the accepted procedure for enlisting military recruits—referred to by the tribe as the qaumi, or “tribal,” method—had been for individual tribes to supply a certain number of men of their own choosing; these men would always serve together and generally in locations that were not far removed from their homes. [5] For several years prior to the uprising, however, the government had insisted on employing a system referred to as nufus, or “population,” in which the army conscripted its recruits directly from the population without consultation with any tribal body. The previous system of conscription was clearly beneficial to the tribe—especially the tribal elders, who decided who would serve. Under this system, the government recognized the tribes as part of the institutional apparatus of governance, and it also implicitly allowed the tribes to share in the exercise of force in the kingdom.

Underlying this arrangement was the practical reality of tribal power, dramatically demonstrated in the overthrow of Amanullah, who had switched to the nufus system; his successor, Nadir Shah, reverted to the traditional qaumi procedures. By the late 1940s, however, the government apparently felt itself to be in a stronger position in relation to the tribes and able to consolidate its position by eliminating the intermediate role of tribal elders in the recruitment process. A group of Safi leaders in the Mazar Valley resisted this initiative, however, and precipitated hostilities by capturing a detachment of troops that had been sent to collect conscripts. Following this incident, fighting quickly spread to the neighboring Waigal and Pech valleys, and before long all four of the Safi valleys (Pech, Mazar, Nur, Waigal) were involved in the insurrection, which continued for the better part of a year.

Wakil’s father, probably in his late fifties or early sixties when the Safi uprising broke out, was prosperous by local standards. According to Wakil, few people had as much land as Sultan Muhammad or such a big family: he had nine wives (although never more than four at a time, as allowed under Islamic law), along with eleven sons and thirteen daughters. However, as fortunate as his life had turned out to be, Sultan Muhammad’s prosperity could not be considered an unmitigated blessing. The more a man has, the more he has to lose, and never more so than in a time of strife such as the Safi War. Younger men could fight their battles, then flee to the mountains until it was safe to come down. For the man of property though—a “heavy man” (drund salai) in Pakhtun parlance—fighting the good fight was not as easy or straightforward, and consequently Sultan Muhammad, according to Wakil, demurred initially when others asked him to lend his support to the cause: “Listen Brother, you’re alone. You have a cart. You can put a bed in it. Your wife is stronger than our men. She can travel easily in the mountains. She can endure hunger. My wives are like invalids. Where could I take them? Even if we tried very hard, it would be impossible for us to move all our property. I can’t do these things. I can’t, but you can.” [6]

Sultan Muhammad resisted the commencement of hostilities and offered little encouragement to those among his tribe who first took up arms, but by the end of the rebellion he was considered one of the insurrection’s leaders. The primary event responsible for propelling Sultan Muhammad into the ranks of the rebels appears to have been an encounter with General Daud following the looting of the government treasury at the provincial capital of Chaga Serai. Until this meeting, Sultan Muhammad’s had been a voice of moderation in the tribe, but the confrontation with Daud changed all that, pushing him openly into the dissident camp and creating an enmity between the two men that continued until Sultan Muhammad’s death twenty years later.

The story that Safi told me of the confrontation between his father and Daud pivoted around an act of arrogance (kibr) on the part of the general. At one point during the meeting in the capital, he told the tribal elders, “If I give the order to my brave and courageous soldiers, you of the Safi tribe will surrender your rifles as though they were canes; you will turn them over like wooden walking sticks.” In response to Daud’s insult and threat to disarm them, Sultan Muhammad stood up and challenged the general, telling him, “These soldiers whom you call brave and courageous are the brothers and children that we have given you to protect the soil, the homeland, honor, Islam, and they must be used for this. You should not set brother against brother. How is it that my brother, who happens to be a soldier, is courageous but I am not? You should regret all that you have said and not say it again.” [7]

Sultan Muhammad was inspired to challenge Daud because of the nature of his threat. As Daud understood, taking away a tribesman’s rifle was morally equivalent to raping the women of his family. [8] A man’s rifle was categorized along with his land and his wife as his namus, which can be translated as both the substance of a man’s honor and that which is subject to violation and must be defended. The threat to have soldiers take away rifles as though they were the canes of old men was an attack on the elders as individuals and tantamount to a declaration that they and their tribe were impotent and incapable of protecting themselves against the basest sort of assault. In defending himself and his tribe against Daud’s insult, Sultan Muhammad took the moral ground away from Daud and humiliated him in front of the elders. According to Wakil, Daud never forgave Sultan Muhammad for the rebuke and used the pretext of the Safi uprising to sentence him to death, along with the rebel leaders more directly responsible for the insurrection.

Honor and Revenge

Following the defeat of the Safis, Wakil’s family, along with hundreds of others from their tribe, were exiled to the western city of Herat. During the first part of their exile, Sultan Muhammad was awaiting execution until Zahir Shah granted him a reprieve on the day of his scheduled hanging. Thereafter, he remained in prison, first in Herat, then in Mazar-i Sharif and other northern provinces until he was finally released during the period of democratic liberalization in the late 1960s. Sultan Muhammad’s family was free during his imprisonment, but they remained nearby, providing food and other resources.

In many ways, the most vivid of Wakil’s stories are those that date from his first years in Herat. This period of exile was not a time of isolation for the boy. A number of other Safi families accompanied them to Herat, and his own family included not only the several wives and numerous offspring of Sultan Muhammad but also various uncles and their families. The first story Safi told me of his time in Herat comes from the first days after their arrival, when the older members of his family believed that Sultan Muhammad would soon be executed by the government. For the family, this period was clearly a time of anguish and uncertainty, for not only was the family patriarch languishing in prison awaiting his death, but most of the other senior males of the family were also locked up in the Herat prison, where they were serving shorter sentences for their part in the recent hostilities. The first story that Wakil told of this period of exile has a feeling similar to that of his story of the soldiers coming to take his family from Pech. It is the quality of a fragmentary childhood memory, sharply focused in some places, but blurred in others:

One time—this happened when we were in Herat—my uncle told me to stay out. I was small, but the adults—my older brothers and uncles and cousins—met together in a room in the compound. One of my uncles was in prison. It was the other [uncle], but he had undoubtedly been in touch with [his brothers] in prison. They had gotten [his father’s and other brother’s] consent, and they were talking it over here.

Now I recall a letter that was written in green ink. I was watching from the doorway and listening to hear what they were saying. I was small, and they wouldn’t let me [be present]. They decided that since my father was under a sentence of death, they had to do something. “Since there is no way we can enable the women and children to escape, we will have to leave all of them in the house and then set it on fire. After that, the rest of us will escape. We will escape and go to the border. If we have the power, we will avenge our father. If we don’t, then we will move from place to place like madmen, like Majnun we will wander in the mountains. But, for us it would be very shameful if they killed our father while we remained in prison or continued living here.” [9]

As the narrator remembered the scene, he was a boy standing outside a room, straining to hear what was going on behind the closed door. Too young to be among the adults, he was old enough to sense the importance of the meeting. The memory was fuzzy, but a distinct image came to mind of a letter written in green ink. The adult Wakil could piece together what undoubtedly eluded him as a child: that the letter was probably written by the uncle who was then incarcerated in the Herat prison. That uncle would probably have been Abdul Qudus, Sultan Muhammad’s brother and the senior member of the family after Sultan Muhammad. The fact that the letter was etched in the adult’s memory indicates that the boy somehow knew it to be significant, but at the time Wakil did not fully realize that the letter was effectively a writ of execution for the boy and much of his family.

The voice coming from behind the closed door was unidentified, but the passage seems too well composed and complete to have been overheard and remembered almost forty years later. One senses that the boy must have later on pieced together snippets of overheard speech into a single coherent speech. Or maybe he did hear all these words, and maybe he was just old enough to understand what they meant, and this understanding permanently seared the words in his memory. We cannot know and perhaps cannot even guess unless we have been afflicted ourselves with such memories. For the men talking among themselves behind closed doors, it was a question of honor. The sons and kinsmen of Sultan Muhammad could not remain inactive while the great man himself was executed by the government. Revenge had to be taken; if it was not, then they had to relinquish any pretense to being men of honor. The usual routines could not go on under such conditions. Just as Sultan Muhammad had once had to leave his child behind to avenge his father, so his sons and kinsmen had to abandon the pleasures of domesticity until their relative’s death could be avenged. Since the enemy responsible for Sultan Muhammad’s death was not other tribesmen but the government itself, vengeance would not be easy to obtain. How, after all, was a group of (presumably) weaponless tribesmen hundreds of miles from their homeland to wreak vengeance on their enemies, and just who was it they should target as the responsible party?

The logic of honor does not translate easily to the more impersonal realm of tribe/state relations, so it is not surprising that the kinsmen of Sultan Muhammad were forced to imagine the unimaginable: the physical annihilation of the dependent members of their family and their own assignment to the liminal realm of the dispossessed, where they would wander until their deaths in the wilder regions of place and mind. The kinsmen of Sultan Muhammad thus envisioned themselves as incarnations of Majnun, the classic figure of romantic tragedy in Afghan folklore, whose love for the beautiful Leila was forestalled when her father married her to another. Before his death from grief, Majnun (whose name has come to be synonymous with madness) wandered in the desert, heedless of who he was or where he was going. Majnun’s love was so deep that, with the loss of the beloved, life itself became a trackless void. In similar fashion, the kinsmen of Sultan Muhammad recognized the impossibility of living a normal life in the absence of honor.

Majnun may be cited as the model for this sort of single-minded obsession, but we know that Sultan Muhammad himself was the model his kinsmen were emulating. Having such a man as the family patriarch imposed a special burden on his kinsmen, and the family elders responded in what must have seemed to them an appropriate manner to the prospect of Sultan Muhammad’s execution. It was one thing, though, for the men of the family to choose their path of vengeance, but one wonders what effect this plan must have had on the boy who overheard it and who was among those condemned to die. He and the other dependents in the house were to be the lambs on this sacrificial altar. If the plan succeeded, they were destined to become—quite literally—burnt offerings to honor, with no hope of some ultimate vindication or even of a future spent in heroic renunciation.

Since Wakil never informed me of his response to hearing the news of his impending death, I can only speculate what it might have been. Much later, he would have understood the cultural terms of his predicament, but, as a small child, he would have been old enough to understand only the words that were being said and their immediate import—not their larger significance or what was at stake for his family. The boy could not have made sense of or cared about these matters, and consequently I wonder in what ways this scene left its scars on him as he grew up. In particular, I wonder to what extent the adult Wakil’s more self-conscious and ambivalent attitude toward the ethos of honor wasn’t determined in part by his having witnessed this peculiar primal scene. Was Wakil’s later ability to self-consciously deconstruct the imperatives of honor in any way connected to such early experiences?

Wakil was a man who, when I met him, had never spent any significant periods of time outside Afghanistan, yet he had an uncanny capacity for reflecting analytically and dispassionately on the cultural logic of past and present events. Unlike the vast majority of tribal men whom I have interviewed and gotten to know—including many who have been abroad—Wakil had a keen ability to analyze his own society and anticipate how I, as an outsider, would respond as I learned more and more about its idiosyncrasies. This ability to see and interpret his own culture from the outside indicated to me that he also understood on some level that his society’s truths were constructed, not absolute, and I have wondered whether this sense wasn’t first instilled when he overheard his own sentence of death. Be that as it may, the plan was never carried out since word arrived after this meeting that the king had commuted Sultan Muhammad’s sentence of death.

Imprisonment and Relocation

I’ll tell you of an incident that happened when I was a boy. This story happened in Mazar-i Sharif. . . . Since I was small, I would take some books and pens and papers and go to the prison, where I would study with my uncle. Every day in the morning, I would study with my uncle or my brother, who was also in prison, and then in the late afternoon I would return home with my cousin.

There is a room on the upper story of the prison. One day we were sitting there studying when we heard it announced that Muhammad Aref Khan, the minister of defense had arrived. All the soldiers there came to attention since the minister of defense was in the prison. Many members of the Safi tribe who were in prison had decided not to accept any land in Mazar-i Sharif: “Our land—whether it is good or bad—is in Kunar, and one stone, one seed on that land is adequate for us. It is our homeland. We grew up there. Even if we decide to move here, it will be under our own authority. We will not take this land that you are imposing on us. We will not give up this [land in Kunar] to take that [land in Mazar-i Sharif]. This would separate us from our tribe. We won’t do this.” They decided this.

I am witnessing this from above. I am watching to see what happens. The tribe is standing all around. The soldiers are also standing. Muhammad Aref Khan is still living. He was next to a very large canal that flowed through the courtyard of the prison in Mazar. Alongside of this, flowerbeds had been planted. [Muhammad Aref] was sitting there in a chair. My father—only my father—was sitting in a chair across from him. They were talking, and he told my father, “You must accept this land. It’s so valuable, and this and that. However much land you want. I will give as much land as you want to whomever you want.”

My father replied to him, “You have your authority, and I have mine. If we are talking about the authority of the government, the situation is clear. You have taken my land, and I am in prison. If you wanted to, you could kill my children. My hands and feet are tied. You can kill all of us if you want. You can do whatever you desire. It’s up to you—what can I do? It is up to you. What is within my authority? I can refuse to give you one stone of Kunar for all of Mazar. If you were to give me the whole province of Mazar, I would not give you one stone from Morchel in Pech Valley. That is my right.” He said this with great force.

They argued on and on about this, but nothing came of it until finally [Muhammad Aref] told him that “the government has the power to force you.”

My father said to him, “Yes, that is your way. Standing behind you is the army, the armed forces, soldiers. It is your custom to capture someone, push them around, and beat them. This is all through the force of soldiers and arms. But if I were to take this uniform of yours off your body, and I went in among the people, and you were also to go, you wouldn’t find anyone who would flatter or pay any attention to you. Your power is the power of the government, but if the power of the government—these soldiers, the army—if these were not there and the political power was not in your hands, then you wouldn’t even qualify as my servant!”

This was a form of insult [paighur]. If something was in my father’s mind, it was also on his tongue. Truly, that’s the kind of man my father was. He was not afraid of this kind of talk. He was only satisfied when he spoke his mind and let whatever was going to happen just happen.

Then this Muhammad Aref threw a punch at my father. He hit him with a punch, and my father grabbed him by the belt. It was the kind of belt that had a buckle attached to it. When he grabbed the belt in his hand, it came apart, and then Muhammad Aref Khan jumped over the canal and shouted behind him, “Soldiers, soldiers, soldiers, soldiers!” My father was left on this side, and he jumped to the other side. Then the soldiers picked my father up by his two hands and two feet. They picked him up and beat him severely. In the course of the beating, his hand was broken, and the bone came out through the skin. It was just hanging down, and [he] was holding onto it.

My father raised his head, and Muhammad Aref said, “Enough!” He was thinking that certainly he had been convinced and would take the land. But my father said to him, “You are infidels [kufr]! You’re not Muslims!” What he meant was that they didn’t have compassion [rahm]. “Tell your men that they have injured my arm! The bone is broken!”

A strip of flesh was hanging down from his arm. Eight men lifted him up, and two men hit him with a stick from this side and two from the other. “At least take my hand.” Then they held his arm [off to the side] and hit him some more. His clothes were white, but it looked as though they had hung them on a piece of meat and then beaten it with a club. It was all cut up and bloody.

I saw this situation from behind; [I saw how they] had picked him up and beaten him. My older brother . . . was also in prison with my father. The soldiers grabbed him, and he started yelling at them and picked up a brick to throw at them. The other prisoners in that prison were all from our tribe, they also picked up bricks. It was like a rain of bricks, but the soldiers—it was really a small army—they were on the other side, and some of them took [my father] in one direction, and others went toward the other prisoners, throwing four or five in each cell and locking them up.

All this was still going on when I left the prison and ran home. I was afraid. When I arrived at the house, I didn’t say a word because—before I had left the prison—one of my brothers had said to me, “Be careful that you don’t say anything when you get home. Be sure no one at home hears about this, that you don’t tell the kids and the women and people we know.”

I went and quietly sat down—silent and stunned. I thought that my father had surely died from this beating. Then I saw the brother who had spoken to me and who had been in the prison come in. He was free. He wasn’t in prison. He had a little box in his hand when he came in. He went into his room. I realized that he had brought something. Maybe it was my father’s clothes. I was looking through a crack, and saw that my brother—he was a young man at the time, about eighteen or nineteen years old—he had taken my father’s clothes like this, and he was holding them over his eyes and crying. He had latched the door so that no one could come in. He was sitting in his own room with the clothes pressed against his face like this.

I saw this scene. I saw this scene and suddenly burst into tears, sobbing. Then my brother came out, aimed a stone at me, and I fled. He was angry because he didn’t want anyone to find out. [10]

Sultan Muhammad and the other Safis had been in prison in Herat for about a year when the order arrived from Kabul that they were to be transferred to a prison in Mazar-i Sharif and that the exiled Safi families would also be given land in the north. Since the reign of Abdur Rahman, the government had used the northern plains of the country as a site for relocating dissident Pakhtun tribes. One such mass resettlement occurred after the Ghilzai Uprising in 1886–1888, and many other small outbreaks had ended with the perpetrators relocating in the north. Resettlement accomplished the double goal of removing troublemakers from the heartland of the kingdom and seeding the ethnically distinct northern areas, where Turkic and Tajik populations predominated, with Pakhtuns. As Abdur Rahman had guessed, Pakhtuns who created difficulties for the government in their home areas tended to become loyalists of the Pakhtun-dominated Kabul government once they were placed in areas where they were in the minority, especially when surrounded by Uzbeks, who had long been their enemies. [11]

In the case of the Safis, the government decided to provide generous tracts of land to the families while the prisoners continued to serve their sentences. The government’s intention was to encourage the Safis to stay on in the north even after their prison terms had expired, and eventually that is what tended to happen: many families decided to settle in the north rather than return to their relatively impoverished native valleys in Kunar. In the short run, however, the government plan ran into considerable opposition as many Safi leaders recognized the government’s intention to split off the dissident leaders from the rest of the tribe. Sultan Muhammad was one of those most steadfastly opposed to taking the land, and this refusal estranged him from some of his fellow Safis, as well as earning him the animosity of the officials who were trying to co-opt tribal support. [12]

In the story of Sultan Muhammad’s beating, several narrative elements stand out. First one gets a sense of the illicit nature of the events depicted because of the observer’s having witnessed these scenes from a place of hiding. It is the same sense that one gets from the tale of Wakil eavesdropping on his elder kinsmen in Herat. In that story, the boy was listening from outside a door to a conversation being carried on inside. Here, the boy was watching, unnoticed, from a balcony of the prison as his father was beaten, and then later we see him again looking through a crack at his brother weeping over the bloodstained clothing of their father. In each of these scenes, the boy has unintentionally become a witness to adult concerns that are beyond his ken. He has intruded into a realm of violence from which children are normally excluded, and this presence makes the actions described all the more startling.

A second feature of this story that is found in the others as well is the sense of helplessness it conveys. In every story that Wakil recounted from his childhood, he is seen as powerless to affect the outcome of events, and this quality is made all the more dramatic for being demonstrated in relation to the larger-than-life figure of Sultan Muhammad. The son was not the father however. He seems, in many respects, a more interesting and empathetic character because he is more human and introspective than his father appears to have been and because he seems capable in a way that his father never was of revealing parts of himself. The father kept his emotions tightly leashed. Wakil does not. He tells of his fear, and in his personal history he allows himself to be pitiable in a way that the father probably would not have. At the same time, however, Wakil is still the son of a great man, and the prevailing tension in his life—a tension that is first hinted at in these early memories—is how he will live up to his father’s example.

A final element of the story is the brutality itself and the boy’s response to it. In Afghan prisons during the time Sultan Muhammad was incarcerated, the wealthier and more influential prisoners received better treatment than the poorer men. Thus, if you had the money to buy food or other commodities, you could purchase them through the guards or have your family bring them to you on a regular basis. Those who had nothing had to work for other prisoners or do other services to receive anything beyond bread and gruel. This feature of the prison system meant that Wakil was frequently enlisted to carry supplies to his imprisoned relatives and consequently saw firsthand the degradation that went on behind the prison walls. On many occasions, he witnessed the poverty and debasement of the prison’s lower classes and the brutality of the guards; these experiences left their mark on him and made him sympathetic to leftist calls for social and economic reform. Even as he rejected the way radical leaders wanted to transform the country and how they went about taking power, he still understood the need for social change. [13]

In the years to come, the government moved Sultan Muhammad to various prisons, sending him finally to Shebargan (in northwest Juzjan Province), which was about as far from Kunar as the government could send him and a place—to quote Wakil—“where people don’t even understand Persian, much less Pakhtu.” To increase the family’s isolation, the government split it up so that only the wives and dependent children of Sultan Muhammad were allowed to accompany him while his brothers and grown sons remained in prison in Balkh. As a result, Wakil grew up far from his own society, in a family environment dominated by women and in an alien social milieu where the language and customs were unfamiliar to him. His was thus a hybrid upbringing, surrounded beyond the compound walls by Turkmen, Uzbeks, and Tajiks, but overshadowed within by the powerful but absent father.

Pech Valley itself was a distant memory, and while he certainly knew about the culture of honor that flourished there, his must have been a largely abstract familiarity since he did not have around him the society of close tribal kinsmen in relation to whom the principles of honor have traditionally been first assayed. [14] While his familiarity with the life of his people was in many ways deficient, one advantage that Wakil had beyond those of his Safi peers was a wider exposure to different cultures and a substantial education. As a result of his peripatetic upbringing, Wakil became conversant in several languages and fluent in Dari Persian, the Afghan lingua franca, and he also had the opportunity to continue his education through the secondary and then the university levels, opportunities relatively few Safi boys had.

The Failure of Democracy

All told, Sultan Muhammad spent over twenty years in prison and was among the last Safis to be allowed to return to Pech. But, even before receiving permission to return home, the family was able to move to Kabul, which enabled Wakil to continue his education and, in the process, receive his first exposure to the ideological struggles that were beginning to reshape the landscape of Afghan political culture. In 1964, the year of Wakil’s arrival in Kabul and his enrollment at the university, Zahir Shah gave permission for the drafting of the nation’s first truly democratic constitution, which was followed in 1965 by the passage of laws permitting the establishment of newspapers and political parties. The university was the site of the most radical and outspoken political activity in the capital, and while he was involved in the campus debates of the time and witnessed the first mass demonstrations, Wakil reports that he did not participate in or seek to join any of the political parties that were then beginning to actively recruit members among the student population. Wakil was living away from the campus in a small house that his family had rented rather than in a dormitory on campus, and this appears to have insulated him somewhat from the more extreme political movements, which were attracting many students. He also seems to have been put off by ideologues from both sides, and while he took an active interest in the political questions that were then dominating discussion, the influence he cites as critical to the development of his own political thinking was not Karl Marx or Mao Tse-tung, Sayyid Qutb or Maulana Maududi—the theorists who inspired the more radical students—but an unnamed American political scientist then teaching at the university, who “smoked a cigar and gave us the best lectures covering every nation in the world—East and West—and which ones had come closest to putting democracy into action.”

Politics and Prestige

I graduated from the university in 1967. My father was in Kabul for that year. Then he returned to the homeland. There were many people there who greeted him. Prior to my father’s return, some people who had been spies during the time of the Safi War were given our lands. They took these lands by force while we were in exile. The people who had taken our lands included some maleks [chiefs] and other influential people. Other Safis who had been exiled also had their land forcibly confiscated by the government. These people who had previously spied were opposed to our return and were saying, “If they come back to their homeland it is possible that some riot will occur again in Kunar. It isn’t wise to let them come back.” Their objective in this was the land that they had gotten hold of. They wanted to keep this land in their hands.

Before my father went back to Kunar, they were telling the government that if we were to come the people would be unhappy, but when my father returned to Kunar, the people gathered in Bar Kandi, the first village at the beginning of Pech Valley, and, based on tribal customs, they fired their rifles and took care of us. This tribal hospitality [melma palinai] continued for about a year. It wasn’t over for a year, and during that year people would come to our house to greet my father and pay their respects.

It was at that time that I graduated from the university, and I wanted to finish up my period of military training and obligation, and I was accepted into the army for training. After one year of training, the people of Pech Valley told me that the election campaign for the thirteenth session of the lower house of parliament [wolesi jirga] was beginning and that I had to be a candidate. I went to talk to my father. One of my stepmothers, the mother of Matiullah, who is now a commander in the jihad, was sitting there. No one else was present, and I told my father that it was my desire to run as a candidate for parliament and he must give his permission since I was responding to the wish of the people.

My father said to me, “My boy, we have seen many difficulties. We have been thrown in prison, and all of this was solely for the prestige [haysiat] of our family. For the sake of this, I have sacrificed my property, my life, my children. I have sacrificed everything for my reputation [naminek], and you should look at this position the same way that you view the earth.”

I said, “There’s nothing wrong with being a representative.”

He replied, “The governments of the present are not the type of government that represent the people. In this government, not even a hundred people could benefit from your service. It’s all right for your own affairs. For your own interests, a seat in the parliament is very good. In this position, you will lose the reputation that I have among the people of my own tribe. People expect something to be done, and you won’t have the power to do it if you want to continue eating the bread of your position. I refuse to give you my permission.”

This conversation with my father occurred when I was in [military] training. On January 1, 1967, my father died at the age of between eighty and eighty-five. After this, because of the expectations of the people, I prepared myself to become a candidate. For the dignity of our family, I participated in the forty-day ceremony that took place after the burial of my father, and I was exempted for these forty days from military training. During this period, I began my candidacy. [15]

Wakil’s willingness to run for office against his father’s wishes indicates that he had taken the class lessons on democracy to heart, but it reveals other things as well. First, it reminds us that in Afghanistan prestige was still largely an inherited asset. A man could certainly lose the status he gained by descent from a famous father, but—as the example of Nur Muhammad Taraki would later prove—it was not so easy to rise to a position of prominence without the proper background. Thus, Wakil, an army conscript barely out of university and away from his home area for most of his life, was nevertheless in a position to run for parliamentary deputy by virtue of his being Sultan Muhammad’s son. However, as Sultan Muhammad reminds his son, he was also in a position to squander that status and, in the process, squander the reputation of his family.

A second feature of this story involves Wakil’s act of disobedience to his father, an act that mirrors a pivotal moment in Sultan Muhammad’s life as recounted in Heroes of the Age. Sultan Muhammad had rushed to the side of his father, Talabuddin, when he had just been struck by the bullets of his killers. In his desire to assure himself a martyr’s reward, Talabuddin had ordered his son not to seek revenge for his murder. Sultan Muhammad, however, had denied his father’s dying request, telling him that it was his duty as a son and a Safi to avenge his murder. Sultan Muhammad’s last command to his son—that he not run for parliament—was likewise premised on his desire to preserve what was most valuable to him—in his case, his reputation as a man of honor. This story, like its predecessor, occurred against a backdrop of conflict in which rivals are willing to use underhanded means to steal the family’s land and usurp its political position. The tribe as a whole, however, supported the beleaguered family, although in both instances the son had to take a stand that violated his father’s determination of what was in his own and the family’s best interest. For Sultan Muhammad, that stand involved making an oath to avenge his father’s death. For Wakil, the stand involved running for elective office, which he believed would enhance the prestige of the family while also providing him an opportunity to participate in shaping Afghanistan’s future.

For both Sultan Muhammad and his son, the events that ensued after their decisions to disobey their fathers were defining moments in their lives. In Sultan Muhammad’s case, his vow to avenge his father led to his fashioning an elaborate and risky plan for destroying his enemies in a single, fell stroke. To accomplish his plan, he had to enlist the assistance of kinsmen and old family retainers who pledged their help to the boy not for himself but for the sake of the father and the family. A similar scenario played itself out in Wakil’s case as well, as those who supported Wakil’s candidacy conveyed to him the same message that his father had received as he prepared for his defining test:

People were coming at that time for the elections. They were coming. It was in the course of the election, and some of the elders were saying into my ear, “We don’t know you, if you are good or bad, if you will serve the people or not, since your life has been passed in Mazar-i Sharif and Kabul. You shouldn’t think that we are giving our votes to you.” This is what they said. “Don’t think that we’re giving our votes to you. We are giving them to the dead bones of your father.” [16]

In response to this message, Wakil invited the people of his area to a great feast in Ningalam, the administrative center of Pech Valley. The feast was held following prayers on the Friday before the election, and it attracted a great crowd:

We killed some cows, and gathered the whole tribe together. . . . I went onto a stage and told the people, “If you think that once I become your representative, then you’ll be in a flower garden, or that I can bring down the sky for you, this isn’t within my power.” I explained to them that . . . my father had not given me his permission. My father’s point was that these governments are not the kind that will allow you to serve the people—you can’t [help] even one hundred people. But I persuaded the people that I had become a candidate in opposition to the advice of my father and that my only goal in doing so was to take a stand in the election, not to win it. [I told them,] “All of you have the right to be a candidate. It’s only a question of struggle, and in reality it’s a matter of making sure that this democracy that the king of Afghanistan claims to have implemented in the constitutional law must be brought into existence by you the people of Afghanistan. This will bring democracy into existence—not the king or any person. Through these struggles, the election becomes very honorable, not by being pessimistic or that kind of thing. Everyone has the right to be a candidate and everyone has the right to vote for whomever they choose.” [17]

Wakil’s speech sought to transect the divide between the morality of honor and the principles of democracy, and it also made it appear that the distance between them was not all that great. Both honor and democracy, after all, were premised on notions of equality and individual agency, both demanded a degree of independent thought and action for those who constituted the community, and both conspired in their own way against the rise of tyrants. On a practical level, as well, it would seem that democracy was on a sure footing in this milieu given the existence of the tradition of jirga (assembly), in which male elders sit together and reach collective decisions on all manner of problems, from guilt and punishment to water use and taxation, war and peace. Wakil played on the points of similarity between honor and democracy, and it would appear from what he said that democracy as a system of government had found a naturally fertile ground in which to grow.

Such was not the case however. The democratic tradition never took root in Afghanistan, and while many practical reasons could be cited—having to do with how democratic institutions were established—there were also ideological reasons, which can be seen at the grassroots in accounts such as this one. In particular, one can see some of the fundamental, if not immediately self-evident, differences between honor and democracy in Wakil’s story of the opposition that his candidacy inspired. One source of opposition, which continued even after his father’s death, was from within his own family. Wakil was the youngest of eleven sons, and some of his brothers were much older than he—old enough, in fact, to be his father. Unlike Wakil, these older brothers were adults when the family was exiled, and they had been more directly immersed in Pakhtun culture than their younger sibling and were also less educated. Some of Wakil’s older siblings shared their father’s view that Wakil’s running for parliament would place the family’s honor at risk, not because they didn’t want him associating with the government but because they were fearful that he might lose. In the words of one of Wakil’s kinsmen (quoted by Wakil), “If a man becomes a candidate and is unsuccessful, this would be a great defeat for him and would place him under threat from his rival. And if the government doesn’t want him to be elected and succeeds in having him defeated, then this failure would actually be thought of by the people as a humiliating insult.”

This conflation of personal shame and electoral defeat illustrates one of the obstacles that democracy faced in adapting to Afghan soil. In the view of many of his kinsmen, Wakil’s loss would have been interpreted by the society at large as an insult directed at the father and the family, not just as the defeat of the individual himself or a rejection of his ideas. When the unnamed relative said that an electoral defeat would be an insult to the family, he implicitly foreshadowed what would have to happen if such a defeat were to occur. Insults must be avenged. A man who has suffered humiliation at the hands of another must redress that humiliation through action. But who exactly could be held responsible? The voters? The rival candidate? Government officials who might rig the election? In this context, an election was not just about candidates and their ideas. It was also about families and family honor, and those who entered the arena placed themselves in a situation in which they allowed others to determine their destiny—a position in tribal culture that is to be avoided at all costs.

In the election Wakil described, it was understood that if opposition arose, it would come from among those families that came to prominence after Sultan Muhammad and other Safi leaders had been exiled from the area. Any candidate who opposed Wakil would come from their ranks, and that meant that a defeat at the polls would have constituted solid evidence that the influence of Sultan Muhammad’s family had slipped. Everyone would have been able to see that their rivals had gained strength at their expense, and the likelihood of a direct confrontation between them would have thereby increased immeasurably. Indeed, since defeat would have been interpreted as an insult to the family, a violent confrontation was all but assured.

As his relatives feared, such an opposition did materialize from among the rival families who had stayed in Pech, but a confrontation was avoided, first, because Wakil won handily and, second, because the opposition, perhaps recognizing their disadvantage, intentionally chose a second-tier surrogate to run against Wakil and in this way blunted the humiliation they would have suffered by defeat. Further, Wakil’s rivals protected their position by invoking the general honor of the tribe, as well as Wakil’s own defense of democratic principles, as their reason for running a candidate in the first place. As Wakil tells it, this was their response:

If [Wakil] were to go to the parliament without any opposition, it would be as if we had sent a mulla. This isn’t right. When a mulla turns up, he goes to the front and leads the prayers. No one tells him not to lead the prayers. But, this isn’t the work of a mulla. This business involves the rights of the people of Afghanistan. Everyone has the right to be a candidate. This was Wakil’s own challenge. [18]

The declaration is interesting, not least because it shows the lowly position of mullas in tribal society. Mullas were fine for leading prayers or for giving a religious imprimatur to the results of tribal negotiations. However, their power was largely symbolic, and from the tribal perspective any group that sent such a representative to a national assembly would be either admitting its weakness or declaring its disdain. [19] In any event, Wakil’s rival was not able to muster sufficient votes to constitute a real challenge, and one reason for this failure was the relatively humble status of the challenger. Wakil had declared grandiloquently during his campaign that anyone had the right to run for office, “whether he is a shepherd, a peasant, whether he is poor or wealthy, the son of a khan or the son of a poor man.” [20] However, the reality was that a candidate had to have the resources to play his role properly. If the representative to parliament were a mulla, well, that was one thing, and the statement the tribe would be making in sending such a representative was that the whole business was beneath their concern. But if the representative were to come from a prominent family like Wakil’s, then a different set of expectations was invoked.

A man like Wakil could not just show up and give speeches; he had to play the expected part, which meant speaking eloquently, and—perhaps most important of all—feeding the people. That is to say, the parliamentary representative had to conduct himself in the same way that khans had always done. This was the only model available: if the tribe wasn’t going to send a mulla, then it had to send a khan (or the khan’s representative), and this meant among other things that the representative had to be able to offer largesse to those whose assistance he needed. Wakil was able to. Because of his ancestry, his relative wealth, and the many allies he could claim by virtue of his family ties, he was in a position to mobilize the resources needed to feed a great assembly of people, and his prestige within the tribe thereby increased accordingly.

King and Commoners

The secretary to the king telephoned and asked me to come and see the king. The secretary asked me what time would be convenient for me to come, and I told him that I am always ready to speak with the king of Afghanistan. The secretary then told me to come at nine, but I was about five minutes late. When I arrived at the palace, members of the cabinet, along with some generals, were sitting there in the antechamber. I was led past them directly to the king’s salon. As I was shaking hands, I noticed that His Majesty had written my name at the top of a piece of paper.

I sat down, and right off he asked me a question. “Honorable representative [wakil sahib] of Pech Valley, what do you make of the government, which receives the vote of confidence and broadcasts its voice over Radio Afghanistan? What opinion do you have? A person might think that this government didn’t have the confidence of the parliament since all of the representatives rise to speak against it, but when the vote is taken, then the hands go up, and the vast majority, with the exception of one or two or three people, all give their votes to it. What’s the reason for this?

“That’s one question. My second question has to do with these demonstrations that occur in Kabul. Behind the scenes, there are people who have their hands in orchestrating them, but my question isn’t about them. It is about the children who run to participate in these demonstrations, the shopkeepers, and everyone else who innocently runs along and participates in the demonstrations. What’s the reason for this, that little elementary school kids join in and shout “Long Live” and “Death to” without knowing what they are saying or what the demonstration is about? What’s the reason for this?”

My response to the first question was this. “The parliament is composed of 216 representatives and 216 parties. Those who speak out against the government are under the pressure of public opinion from the whole country of Afghanistan since everyone believes that this government doesn’t represent the people. They have to speak against it so that they can get reelected in the future and not become the object of hatred in their own communities. But then when they vote for the government, it is for their personal reasons. They have their own affairs. They have their own businesses. They vote for the government, [and] then in front of the ministers they can say to them, ‘See, I gave you my vote.’ That way they can do their personal business without losing the support of the people.”

The King then asked, “What’s the solution to this?”

I said, “The solution is that this parliament must be a party parliament. The [Political] Parties Law should be passed, and then one representative from each party can speak instead of all 216 deputies. Then the government can represent the people outside the parliament. Until the government is connected to the real representatives of the people, it won’t feel its responsibility toward them. The kinds of government that nowadays are coming are only thinking about protecting their own positions. They think, ‘For the year or two years or three years that I am here, I have to fool these deputies and the people.’ They only pass their time. This situation will be corrected in this way.”

On the other matter that he asked me about, I gave an example that I had seen with my own eyes one time when I was traveling in Pech Valley:

“Several elders and other people were with me. It was in the dark of night. A woman was sitting by the bank of the river. Something black could be seen, and we could hear the sound of water. Something was being washed.

“I said, ‘Who’s that?’

“Someone replied, ‘It’s a woman.’

“I asked, ‘What’s she doing?’

“He replied, ‘She’s washing clothes.’

“I asked, ‘Why doesn’t she wash during the day?’ (This is what actually happened.)

“He replied, ‘She has nothing else to change into. These are her only clothes, and she washes them at night. She’s sitting there naked under that veil. She washes them, dries them, and puts them on in the morning. She doesn’t have a change of clothes.’”

I told this story to His Majesty. I told him, “This is something that I myself saw.”

Then I told him the story of another incident I had seen in the Badel Valley. I was the guest some place and was on my way there when I came upon a man with a load of barley. He was carrying a huge load of barley on his back. His clothes were torn, and his body was half-naked.

I asked him, “What’s this?”

He replied, “Barley.”

“Where did you buy it?” I asked.

He replied, “I bought it at such-and-such a place and I carried it over the mountains.”

I asked him, “Isn’t any barley grown [where you live]?”

He said, “No, I don’t have anything.” At that time, things weren’t so good, and barley wasn’t available that year.

Then he said, “A man gives me a note that [says], ‘I will give so-and-so the money for the barley.’ As the middle man, I carry the barley back to him. One day and night have passed since my children last ate. I carry this and have the barley made into flour at the mill. Then I leave it for them. Then I go after another job in some other place. Then I buy some more barley and come back.”

I told these two stories to His Majesty. I told him that this was the condition and the economic life of the people. “There are also other people who have nothing to do. They don’t work. They have nothing to worry about: everything is prepared for them, and they don’t have any miseries.”

The king of Afghanistan picked up his cigar and lit it. He placed his glasses on the table. He was sitting opposite me, looking very serious, and he said, “Wakil Sahib of Pech Valley”—this is a quote of King Zahir Shah—he said, “I am not a capitalist.” These are the words of the king of Afghanistan. “But I also don’t want socialism. I don’t want socialism that would bring about the kind of situation [that exists] in Czechoslovakia. I don’t want us to become the servants of Russia or China or the servant of any other place. Here is the government. Here is the people. My effort is to work together with this government and the people. These have been my sincere efforts as king of Afghanistan, and I don’t lie to you.” These were the words of Zahir Shah. [21]

In this account of a meeting with Zahir Shah, Samiullah Safi provides a partial explanation for why democracy failed in Afghanistan. There are two features of this analysis, the first having to do with the government in Kabul and the second with the situation in the country as a whole. The approximate date of this meeting is not indicated, but we can assume that it was sometime after December 2, 1969, when the parliament of which Wakil was a new member had ended an extended period of debate over the status of the government of Prime Minister Nur Ahmad Etemadi. Etemadi had come to power in November 1967 during the session of the twelfth parliament, and he had been reappointed by the king after the election of the thirteenth parliament in September 1969. The newly elected parliament, however, had chosen to exercise its legislative might by subjecting the king’s choice to a prolonged and rancorous debate. From November 13 to December 2, the parliament considered whether to grant the prime minister and his cabinet a vote of confidence. In the course of the debate, the proceedings of which were carried live over Radio Afghanistan, 204 of the 216 parliamentary deputies rose to speak, and the great majority used their moment before the microphone to lash out at government corruption, ineptitude, and inaction. In the end, however, only 16 deputies chose to follow through on their criticism by casting votes of no confidence against the king’s choice of prime minister. [22]

Zahir Shah’s first question to Wakil concerned the apparent incongruity between the vociferous rebuke offered by the parliamentary deputies in their speeches and the tail-wagging compliance seen in the final tally itself. The king’s second question concerned another persistent feature of democratic politics during that era: the participation in antigovernment demonstrations of ordinary people who were not otherwise involved in political affairs. Wakil’s answer to the first question focused on one of the most apparent failings of the democratic system instituted by the king—its prohibition of political parties from involvement in the electoral system.

Political parties were not altogether absent. In 1965, the king had allowed the free publication of newspapers, and the vast majority of papers that came into existence following this decision were party-based organs espousing particular, and for the most part extreme, points of view. Parties therefore existed, including the Soviet-allied Khalq and Parcham parties, and at least briefly they were publicly airing their views in print. However, these parties were not allowed to operate openly within the electoral system because of the government’s fear that they would become too popular if they were legitimated and allowed into the chambers of power.

The decision to keep the parties out of the open political arena was fateful for several reasons. First, it forced the parties to operate outside established channels, and energies that might have been devoted to openly contesting elections were instead turned to the recruitment and organization of covert cells, especially within the government, military units, and schools. Second, as Wakil claims to have told Zahir Shah, the absence of parties in the parliament meant that the proceedings of that body were even more chaotic than they might otherwise have been. Without parties, the parliament consisted of “216 parties,” one for each deputy. Agreements on legislative issues were virtually impossible to arrive at in this atmosphere. On such matters as the no-confidence votes against the prime minister, there were no parties to organize sides pro and con, and so every deputy availed himself of the opportunity to speak his mind. However, when it came time to work on more mundane legislative issues, the throng of deputies usually disappeared. Time and again, parliamentary officers were unable to convene a quorum, and enduring coalitions were all but impossible to arrange and keep together without the organizational apparatus and discipline that parties could provide. [23]

The second question posed by the king, regarding the demonstrations, produced a reply from Wakil that seems in many respects irrelevant. Wakil’s stories of the poor woman doing her wash at night because she had only one set of clothes and of the man carrying barley across the mountains to earn enough to feed his family accurately depicted the conditions of a significant percentage of Afghanistan’s rural population. And the insinuation at the heart of these stories—that the government in Kabul was out of touch with the rural population—was also correct. However, the king’s question had more to do with why people in the city were attracted to radical movements. Why did those who were relatively well off and who benefited directly from the king’s peace thoughtlessly lend their voices to the slogans of radical political parties?

The people that Wakil refers to—the rural poor—had rarely been the beneficiaries of government largesse, but, as noted in the discussion of the Khalqi government’s misconceived program of reform, few would have indulged this expectation. Nor would most of them have been attracted to demonstrations or other radical political options. Never having benefited much from government programs, they had little reason to expect help from this source. Because of his exposure at university to the theories behind various governmental systems and his experience in Pech of some of the extremes of rural poverty, Wakil concluded that it was the government’s job to take care of the poor, but the poor themselves did not necessarily share this conviction. Involvement with the government was as likely to create problems as to solve them, a fact that most rural people well knew and that the Marxists who took power nine years later proved beyond any doubt.