First Major Landscapes

Corinth's tendency to subordinate individual forms to a larger whole may have been a consequence of his growing interest in landscape painting. For in outdoor light he faced a wealth of nuances that demanded to be unified within a broad spatial concept. He responded with vibrant tones that translate light and atmosphere into elements of pictorial energy. Corinth's earlier landscapes are informal studies, undertaken largely as exercises. His landscapes from the 1890s, by comparison, result from a serious and sustained commitment to plein air painting.

Corinth's major landscapes begin with the view he painted in the autumn of 1891 from the window of his studio (see Plate 7). With this painting he continued the German Romantic theme of the "open window," though his reinterpretation of the subject is prosaic, like Menzel's window views in Berlin and Winterthur. Across the gardens and fields that at the time gave Schwabing a rural character, the view extends to church towers and smoking chimneys in the distance. White patches of an early snow intermingle with the green of the meadows, and in the humid air the soil and trees take on a reddish tone. The simplified composition evolves from variations of the surface texture, and both the direction of the brushstrokes and the impasto of the swiftly applied patches of color suggest that the motif was constructed right on the canvas.

Most of Corinth's landscapes from this time were painted during the summer months he spent in the picturesque countryside near Munich. They show a considerable debt to the paintings of the Barbizon school, which after the international exhibition in 1869 had helped to redirect Munich landscape painting, encouraging a more intimate conception of nature in contrast to the

Dutch-inspired vistas popular during the first half of the century. The painters of the Leibl circle, in particular, gave the simplest motif—a clearing in the underbrush or a cluster of shrubs and trees by a brook or a pond—careful and sympathetic attention. Corinth's forest interiors from this time show a similarly circumscribed view. One, the splendid picture now in Dachau (Fig. 38), is painted so freely that the canvas is almost a flickering patchwork of brushstrokes. The others are more controlled and elegiac in mood. The technical and expressive range of these landscapes is illustrated by the painting in Dachau and the Large Landscape with Ravens (Fig. 39) of the same year. The forest scene is a spontaneous visual response to the evanescent effect of bright sunlight breaking through foliage; the landscape indicates a more deliberate approach, with its simplified composition and the predominant shades of purple that reinforce the autumnal mood. As in Caspar David Friedrich's well-known picture in the Kunsthalle in Hamburg, Hill and Ploughed Fields near Dresden (c. 1830s), which Corinth's landscape also resembles structurally, the ravens settle on the harvested fields like harbingers of winter and approaching death.

Corinth's melancholy conception was apparently inspired by the moody landscapes of Walter Leistikow (1865–1908), with whom he sometimes painted in the fall of 1893 near Dachau and at the Starnberger See. Earlier in the year Leistikow had been to Paris, where he was deeply moved by a performance of Maurice Maeterlinck's Pelléas et Mélisande at Lugné-Poé's newly opened Théâtre de l'Oeuvre. Summarizing his impressions of the play, he wrote in the July issue of Die Freie Bühne : "I do not know of anyone who can wield the brush better than this poet. His works are spoken painting. And this performance is one of the greatest works of painting the modern period has brought forth."[53] At the time, Leistikow himself was in the process of abandoning his naturalistic approach to landscape painting in favor of a more evocative rendering. Using simplified patterns of muted colors, he gradually evolved a pictorial language that conveys a gentle and somber mood, as in his landscapes of the Grunewald (Fig. 40), in which dark groups of trees stand silently, silhouetted against the sky and reflected in the waters of a quiet lake or pond.

Leistikow's influence is also evident in the haunting Fishermen's Cemetery at Nidden (see Plate 8), painted in the summer of 1894 when Corinth traveled to East Prussia and the Baltic seashore. The melancholy character of the painting derives not only from the motif but also from the pictorial elements. As in the autumnal landscape in Frankfurt, purplish tones dominate the variegated colors of the sandy soil. Most of the crosses are painted in somber shades of blue

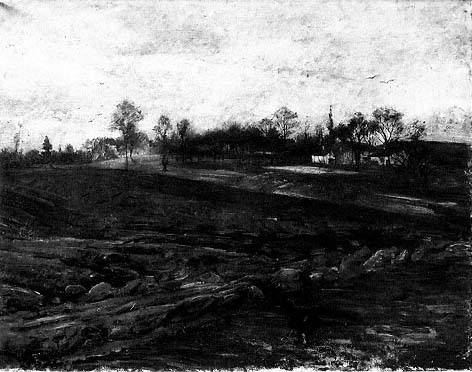

Figure 38

Lovis Corinth, Forest Interior near Dachau , 1893. Oil on canvas, 67 × 86 cm, not in B.-C.

Kunstsammlungen der Stadt Dachau.

Figure 39

Lovis Corinth, Large Landscape with Ravens , 1893. Oil on canvas, 94.5 × 120 cm,

B.-C. 100. Städelsches Kunstinstitut Frankfurt (1912).

Photo: Ursula Edelmann.

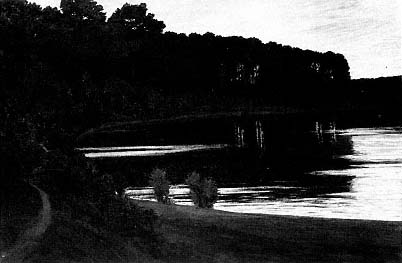

Figure 40

Walter Leistikow, Lake in the Grunewald , c. 1895. Oil on canvas,

167 × 252 cm, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, National-Galerie (DDR).

and brown. Only one grave is still tended; the others lie neglected. Here and there flowers survive among the weeds. There is a strangely anthropomorphic quality to the crosses, which almost seem to gaze out to sea. As in the paintings by Caspar David Friedrich in which human figures, seen from the back, stand transfixed before nature, the viewer's feelings are directed beyond the graves to the open water, where boats glide smoothly along the shore.