World's Columbian Exposition of 1893, Chicago

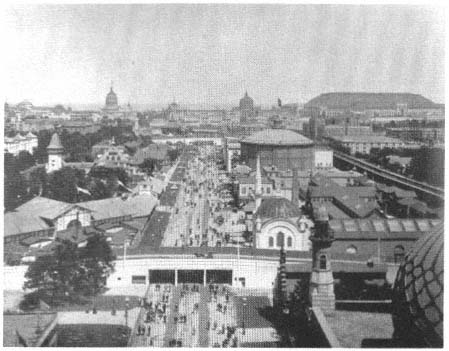

The contrast between the academic planning of the main exhibition and the deliberate haphazardness of the periphery was perhaps nowhere as striking as at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893, held in Chicago (Fig. 42). The World's Fair, as it was commonly called, was a turning point in the history of American architecture. Under the supervision of Daniel Burnham, Jackson Park on the Chicago waterfront was developed into a "dream city," the forerunner of the City Beautiful movement. Burnham had appealed to the par-

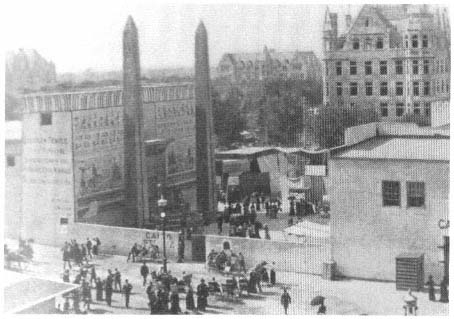

Figure 43.

View of the Midway from the Ferris wheel: (right) the Ottoman quarter, with the

mosque at its entrance, and, next to it, the Egyptian section with obelisks,

Chicago, 1893 (The Dream City, vol. 1).

ticipating architects for uniformity of design—to be achieved by the use of the classical style. Here was a mode in which the leading American architects of the late nineteenth century, most of them trained in the Beaux-Arts system, felt at ease. With the collaboration of the great landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, the "White City" was created, with its lagoons, long axes and vistas, and white classical monuments. The scale was large, and the exhibition was the most complete urban-scale project realized since the planning of Paris and Vienna in the 1860s.

The concern for uniformity in urban design and architecture seemed to disintegrate beyond the main sections on the waterfront. The exotic missions were placed along the Midway Plaisance, an avenue six hundred feet wide that extended for a mile west of the Women's Building (Fig. 43). There was, however, an order in the site plan of the seemingly chaotic national villages.

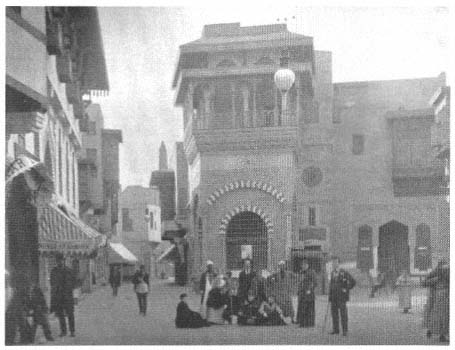

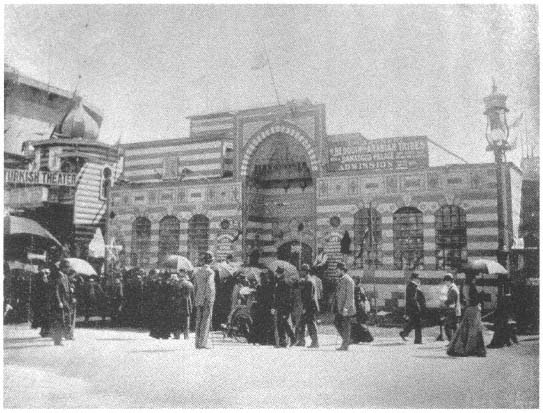

Figure 44.

Entrarce to the Egyptian quarter, Chicago, 1893 (Rossiter, A History of the

World's Columbian Exposition, vol. 2).

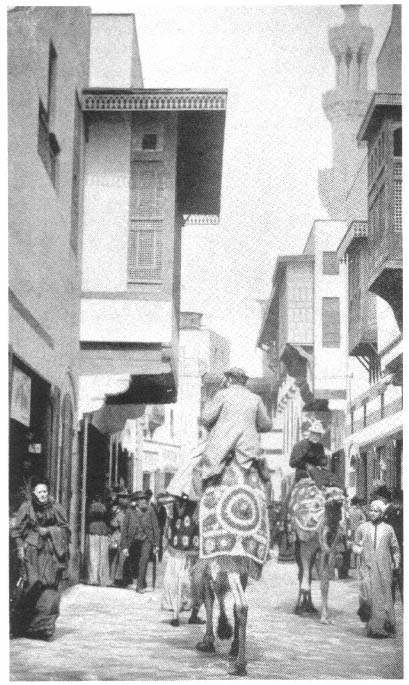

Figure 45.

Cairo Street, Chicago, 1893 (World's Columbian Exposition, vol. 2).

According to a contemporary literary critic, Danton Snider, the Midway was organized as a "sliding scale of humanity. The Teutonic and Celtic races were placed nearest to the White City; farther away was the Islamic world, East and West Africa; at the farthest end were the savage races, the African Dahomey and the North American Indian."[53] The Committee on Ways and Means had decided in advance that the Midway would have an "ethnological and historical significance" and thus some scientific respectability.[54] Echoing the Rue des Nations theme, the committee specified that here

the style of architecture in each case . . . be characteristic of the country represented. It will thus be seen that in addition to the beautiful buildings erected by the Exposition there will also be a grand display of architecture from every part of the world, making the variety of design so extensive as to be bewildering in its outlines.[55]

Thus the indispensable Cairo Street put on its show in Chicago (Fig. 44). Its facade on the Midway had "nothing artistic" about it; passersby had no clue to the life of the street from the plastered exterior wall. But once inside the gate, visitors saw a lively array of shops and houses, a café, the "solemn spectacle" of a mosque,[56] two obelisks, a "Temple of Luxor," and a much talked-about theater where the belly dance was performed.[57] The street itself was "just as crooked as one has a right to expect in a Cairo thoroughfare" (Figs. 45–46). A Chicago Tribune reporter argued that the Egyptian quarter had the "picturesque beauty and strangeness of 'Masr-al-Kahia,' as the natives termed the famous city, which stands near the site of old Babylon." The picturesqueness was enhanced by the projecting upper levels of the buildings:

Beautiful balconies and bow windows are seen, while here and there relief is given by a carved balcony. All the windows are protected by graceful woodwork and many of them are made of stained glass. The shades in the windows are attractive. No paint covers the closely-woven Meshrebieh screens which protect them.[58]

As in Delort de Gleon's Rue du Caire, the materials were shipped from Egypt "in order that Cairo street scenes may be represented,"[59] and consequently the buildings enjoyed "a polish and color that only age could bring."[60]

Figure 46.

Cairo Street, Chicago, 1893 (The Dream City, vol. 1).

The authenticity of the architectural, as well as the social, reproduction pleased many:

Architecturally, the street, long and winding, was perfectly reproduced; the shops were real shops, not mere exhibits, and it required only American money and a kind of polyglot French to strike a bargain. The attendants were Egyptians; and real citizens of Cairo lived in the upper stories of the houses, and loitered or hurried through the street, touching, jostling the cosmopolitan sightseers, who alone seemed foreign here. Donkeys and camels were steeds and vehicles. . . . From an open door came the music of an Oriental theater, and from a balcony hung a girl of sunny Egypt, . . . [and] barefoot babies played around the doorsteps or joined the motley throng that watched an Egyptian juggler on the corner; with a clanking of gilded chains and trapping, a band of pilgrims, camel-mounted, returned from Mecca; or preceded by a waving sword and escorted by many guests, a bride rode camelback to the temple: and up and down the throughfare and in and out of mysterious dark passages moved . . . the normal life of the Egyptian settlement.[61]

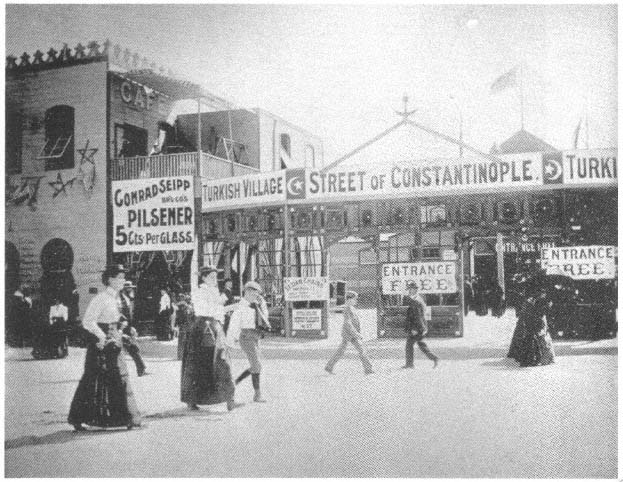

A mosque announced the Ottoman presence on the Midway (see Fig. 43), recalling its more elaborate 1867 counterpart in Paris. The high dome and minaret made the mosque one of the symbols of the Midway while helping to define the entrance to the Turkish Village. The village, also referred to as the Business Street of Constantinople, was designed to recall the Byzantine Hippodrome in the Ottoman capital (Fig. 47). The outstanding feature was an obelisk, a wooden replica of the Egyptian obelisk on the Hippodrome in Istanbul, whose lettering had been transferred to plaster casts, carved on the site in Turkey, and shipped to Chicago in sections. A low balustrade, like that around the original, protected the replica.[62] This was the first display at an exposition of Istanbul's Byzantine past as part of Ottoman culture—it had been added, perhaps, because the Egyptian displays, as well as the Tunisian and Algerian pavilions, included material on ancient history. The Hippodrome, however, was not simply meant as a cultural symbol; it included a track for horse races, and it also served as an entertainment center, where visitors could watch "fantasias and exercises by a number of dromedaries, harnessed and caparisoned according to Arabic fashion." The Arab horses and dromedaries were chosen from the best breeds and shipped to Chicago.[63]

Figure 47.

Entrance to the Street of Constantinopole, Chicago, 1893 ( Glimpses of the World's Fair ).

Figure 48.

Damascus palace, Chicago, 1893 (Glimpses of the World's Fair ).

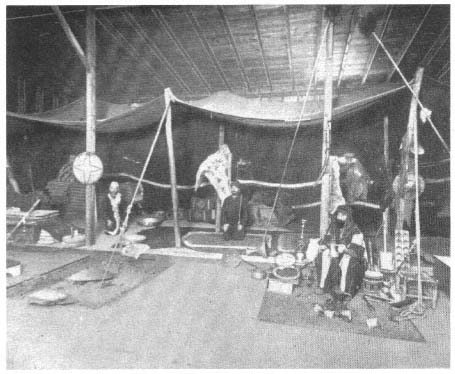

At the center of the village was a Turkish restaurant in a cubical building with a three-tiered facade and overhanging cave that was topped by a small dome. In its overall form and architectural features, this structure repeated the themes of the main Ottoman pavilion in Jackson Park. The rest of the street was lined with shops; there was also a Turkish theater as well as a fortune-teller's tent in front of the obelisk.[64] In the Turkish Village and adjoining the theater, the city of Damascus was represented by a pavilion called the Palace of Damascus, and by an encampment (Figs. 48–49). The palace's large single

Figure 49.

"Camp of Damascus colony," Chicago, 1893 ( World's Columbian Exposition, vol. 2).

room was richly decorated, with a wide divan all around, and in its marble-paved vestibule was an octagonal fountain. Photographs representing Syrian tribal life and characteristic landscapes hung on the walls. In addition to performances in the theater, an "Oriental wedding ceremony" was acted out daily in the palace, complementing the performances in the theater.[65]