Ramnagar: Pilgrims and Singers

Earlier in this chapter I discussed the origins of the Ramlila of Ramnagar, and I devote a later section to its manner of interpreting the Manas text. Since the work of documenting the individual performances of this month-long production has already been undertaken by others, I do not describe specific episodes in detail here.[79] Instead I focus on two aspects of the pageant that have received little attention: the relationship of the performances to a traditional Banarsi pattern of recreation, and the role of the Ramayanis, or Manas chanters.

[79] See the work of Schechner and Hess, referred to in note 4 above.

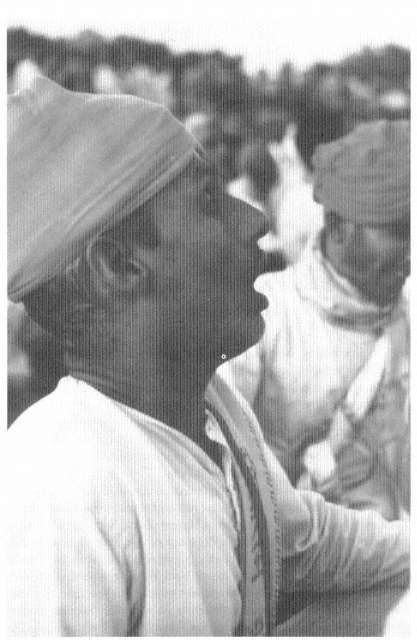

Figure 25.

A procession during the Ramnagar Ramlila (photo courtesy of

Linda Hess)

The Art of Crossing Over It is surely clear to anyone who has ever spent time in the city that the Banarsi way of life consists of more than ritual bathing and visits to temples; even these and other pious activities for which the place is justly famed have (in Western terms) "secular" dimensions that contribute to their appeal. Yet scholarly writings on the city have tended to focus on its theological status and the complex hierarchy of its religious institutions and functionaries, and only recently has a study examined the everyday life of its people, particularly their concept of "Banarsiness" as "an ideology of the good life."[80] Central to this ideology, as Nita Kumar discovered, is a cycle of leisure activities based on indigenous concepts of the person, space, and time, articulated in terms whose importance has often been overlooked "because they perhaps do not fit very neatly into a text-based or ritual-oriented scheme. Among these are the principle of pleasure (khusi , anand ), the philosophy of freedom and carelessness (mauj, masti ), the image of play (khel, krira[*] , lila , manorañjan ) and a stress on individual taste, choice, and passion (sauk )."[81] That Kumar's subjects represent some of the city's poorest artisans (such as metalworkers and woodcarvers) may appear paradoxical; the economic realities of these men's lives—starkly documented at the beginning of her study—do not suggest a great scope for leisure. Yet Kumar vividly catalogs the surprising range of participatory recreations in which artisans engage: poetry and singing clubs (including Ramayan singing groups), Ramlila troupes, wrestling and swimming clubs, and the full array of fairs, temple srngar[*] festivals, processions, and other annual celebrations in the city concerning which a popular saying holds, "Eight days—nine festivals."[82]

Among the most popular recreational activities is the practice known as bahrialang[*] (literally, the "outer side" or "farther shore"), which refers to boating excursions to the opposite bank of the Ganga and to the activities pursued there. In questioning some of the city's poorest artisans concerning their recreational activities, Kumar found that most would at first vehemently deny having any—"Are sahab , what entertainment can we poor people have?" Her inquiry might have ended there, had she not discovered the magic formula bahrialang[*] , at the mention of which the same men would wax eloquent concerning its exquisite pleasures—whether enjoyed daily, weekly, or more infrequently.[83] The essential constituents of the practice are so simple—one

[80] Kumar, "Popular Culture in Urban India," 324.

[81] Kumar, The Artisans of Banaras , 236.

[82] "Ath bar[*] , nau tyauhar"; quoted in Jhingaran, "Ham sevak," 20.

[83] Kumar, The Artisans of Banaras , 83-110, 230.

crosses the Ganga, relieves one's bowels, and washes one's clothes—that an outsider may not readily grasp just what is so recreational about it. But of course, it is never a solitary activity; it is enjoyed with friends, and much time is whiled away in talking, joke telling, and singing. In addition, it provides a complete and much-needed change of environment. I have already mentioned the distinction between the two banks of the river: the city side and the "outer" side. The former is civilized and sacred, but also chokingly congested. The farther shore, in contrast, is a sandy, uninhabited floodplain, an accessible wilderness. As such it offers a refreshing antidote to the crowded bazaars and cramped working and living spaces that otherwise form the boundaries of the city man's life.

There are other dimensions to the excursion as well. Since the outer side is a ritually impure area, it has always been regarded as a good place to relieve oneself, and there is an old tradition that exemplary people repair beyond the sacred borders of the city for this purpose. The appeal of this aspect of the trip must be understood in the context of a culture in which personal hygiene practices are powerfully associated with ideals of purity and deep levels of identity. The journey itself is also pleasing; the river is the city's great scenic attraction as well as its claim to spiritual greatness, and there is no better way to appreciate its beauty than from a boat. The act of crossing the Ganga inevitably has a religious dimension—Banaras, like all pilgrimage centers, is a "crossing-place" (tirthsthan ), where believers are assured safe passage over the turbulent flood of this world—and every Hindu reaches overboard in midstream to sprinkle a few drops of water on his head while uttering a formula such as "He Mata Ganga, teri sada jay!" (O Mother Ganga, may you ever be victorious!). Finally, an essential ingredient in the pastime for many Banarsis is the consumption of bhang and the resultant intoxication. In most excursion parties one man assumes the job of preparing the treat: crushing the leaves and straining a decoction that is then drunk, or shaping the pulp into little balls—combined, if budget will allow, with raisins, nuts, and savory spices—that are eaten. A moderately powerful psychoactive drug that alters visual and time perception, bhang has a religious dimension as well, since it is associated with yogis and their lord, Shiva, who is said to consume great quantities of it. Needless to say, a draft can add a new dimension to mundane activities: one can, for example (as Kumar was gleefully told) seize a bar of soap and spend a satisfying three-quarters-of-an-hour deeply engrossed in laundering one's dhoti.[84]

[84] Ibid., 84.

In his writings on Ramlila , Schechner observes that an important characteristic of Banaras's most famous production is the fact that it is not located in Banaras.[85] By constructing their dramatic environment on the further shore, the royal patrons created a theater that urban residents have to cross the Ganga daily in order to reach. Schechner vividly describes the difficulties and even hazards that this pilgrimage can entail, especially during the early part of lila season when the river is still swollen from monsoon rains. At the very least, the trip is time-consuming; a person coming from the city may require two or more hours simply to reach the lila site. If he is someone whose personal regimen is to witness every performance from beginning to end, attendance will be more than a full-time job, easily occupying ten hours a day. But I am convinced that time is still a relatively cheap commodity in Banaras and that some of the inconvenience that I, for example, experienced in getting to Ramnagar each day was not felt to the same degree by local pilgrims, who seemed to accept the journey itself as part of the recreational experience of lila . For among other things, the Ramnagar Ramlila is a grand, month-long bahrialang[*] excursion with all that this implies.

Many thousands of people attend the Ramnagar pageant sporadically, turning out for big events such as the breaking of Shiva's bow and the slaying of Kumbhakarna. But there is a core group of spectators—probably amounting to one or two thousand—who attend daily. To be able to do so is highly valued. The question I was invariably asked by fellow audience members was "Do you come daily? " and their satisfaction when I answered in the affirmative was evident, for regular attendance is the ideal, although everyone is not able to manage it. The great exemplar of such dedication is the maharaja, the patron and principal spectator.

Those attending daily fall into two categories: sadhus and nonsadhus. As already noted, sadhus in large numbers—mainly Ramanandis—reside in Ramnagar during the month of lila ; special camps are set up for them and daily rations are provided from the maharaja's stores. With their sectarian marks and seamless garments (or lack of them, if they belong to naga , or "naked," orders), the sadhus are a distinctive presence at the festival grounds, where they often cluster around the boy actors to entertain them with devotional singing and ecstatic dancing. But the householder who comes daily from the city is no less readily identifiable, for he too affects a distinctive costume. He is known as a nemi (from niyami , "one who adheres to a regimen") or by its expanded

[85] Schechner, Performative Circumstances , 242-45.

variation, nemi-premi (the latter connoting "lover" or "aficionado"). He typically wears a clean white dhoti and baniyan (T-shirt), a cotton scarf (dupatta[*] ) block-printed in a floral design and tied as a diagonal sash across the chest, and yellow sandalwood paste on the forehead. He goes barefoot—this is part of his regimen—and carries a small wooden stool for comfort as well as protection from dust and mud in the varied environments. He may also carry a bamboo stave with a polished brass or silver head.

According to nemis , their costume has no special significance. Its details are either utilitarian (the staff is a convenience for walking and a protection against dogs when returning home late at night) or else (as in the case of the dhoti and the scarf) simply reflect "the old-time style of Banaras city." Since the Ramnagar production is a self-consciously old-fashioned event, it is appropriate that its core audience dresses accordingly; I have seen spectators change out of Western-style pants and shirt at the riverside, donning nemi dress and placing their carefully folded "work clothes" in a bag. Other aspects of the regimen include a bath in the Ganga before each performance and, of course, daily attendance. This may not mean witnessing all performances in their entirety; many regulars pick and choose among the episodes, giving their full attention only to favorite ones. But all make a point of being present during the concluding arti ceremony each night, when the divine presence is considered strongest. Some staunch nemis observe a daily fast, which they break only after they have had the Lord's darsan at arti time.

Although I initially understood the Ramnagar regimen as a kind of religious austerity, I gradually became aware, in conversations with aficionados, of the sensual and aesthetic richness of the nemi experience. One lila regular of the milkman caste came from a village on the western outskirts of the city. Although he had completed secondary school and was employed in a railway office, this man retained a strong taste for traditional Banarsi pastimes and was a great devotee of bahrialang[*] . Together with a group of friends, he owned a share in a boat kept at Gay Ghat and used for daily excursions throughout much of the year. During the month of lila , however, the boat brought the group to Ramnagar. This man's description of his daily routine during the season was delivered with evident relish and testifies to the pleasures of the pilgrimage for many regular participants:

During lila I go to work very early and leave the office at about 11:00 A.M. I go home and take a light meal, then head for the ghat to meet the others. First we row across to the other side and stop there for a while. We take some

dried fruit and a little bhang—not too much, or we'll get sleepy—then a glass; of water to cool the body. Then we go off and attend to nature's call, then meet and row to Khirki Ghat [at Ramnagar—a strenuous journey against the current; the men row in teams, chanting to set a steady rhythm]. Then have a swim and wash clothes. Then rub down with oil, then dress. Prepare sandal paste and apply it, to cool the forehead. Also a little scent at each ear, according to the weather. Then go for God's darsan .[86]

What kinds of people pursue this "regimen"? Most obviously, of course, men; women in Banarsi society have no part in the practices described here, although they may occasionally enjoy boat rides and excursions in the company of their families, and many women do attend the lila periodically. Not the extremely poor either, or for the most part the very rich. The former lack the resources for the daily outings, for regular attendance at Ramnagar is costly, not merely in the working time lost but in the expense incurred in getting there—to maintain a hired boat, such as the Gay Ghat club did, would probably be considered the ultimate recreational luxury by poorer Banarsis—and in maintaining the proper appearance and being able to afford snacks of tea and pan , if not the many delicious foods sold in concession stalls at the grounds. The wealthy modern-educated classes possess the means to attend but nowadays mostly lack the inclination; their tastes in entertainment have changed. Those men of means who are lila -goers are people who are conspicuous in their adherence to traditional life-styles: temple owners, expounders, Ayurvedic physicians, and socially conservative merchants. The majority of regulars, however, seem to be from the middle and lower-middle classes: small-scale merchants, milkmen, betel sellers—self-employed people who can afford to shutter their shops early for one month each year or leave a relation minding the store—and lower-level office workers and clerks, who can somehow arrange (in the tolerant milieu of Banarsi business) the time away from work. These men have both the means and the inclination to attend, and their presence at the lila is no less an ideological statement than is the maharaja's staging of it. By their daily attendance, clad in their distinctive uniform, they offer an affirmation of their faith not only in Sita-Ram, the Manas , and the maharaja, but in the Banarsi way of life as they conceive of it—a "natural" life of aesthetic intoxication, wholesome outdoor activity, male camaraderie, seasonal celebration, and vociferous piety.

[86] Pyarelal Yadav, interview, October 1982.

The Voice of Lila The melody to which the Manas is sung at most Banaras Ramlilas is known as Narad vani[*] ("Narad's voice," after the divine rhapsodist who is said to have created it) or lilavani[*] , (the voice of lila ), and it shares with other forms of epic recitation an antiphonal pattern requiring two groups of singers. At Ramnagar there are twelve Ramayanis divided into two teams of six; neighborhood productions sometimes have smaller contingents. Musical accompaniment consists of double-headed drums (mrdang[*] ), and brass finger cymbals (jhal or manjira ), which are played by the lead singer.

Perhaps the most striking feature of Naradvani[*] is its stylized, distorting quality, which necessitates frequent minor alterations in the text. These follow a conventional pattern: the singers begin the first line of each stanza with the shouted syllable he! ; subsequent lines are begun with the syllables e-ha ! The end of each half-line is drawn out for five beats and its final vowel replaced by a , sung to a melodic pattern of three descending and two ascending tones. While this concluding pattern is sung by the first group, the second group is ready to join in on the fifth beat, which glides directly into the second half of the line. This too concludes with a , this time held only for the three descending tones, before another e-ha ! from the first group begins the next line. The ends of half-lines must often be adjusted to fit this pattern. If the final word ends with a long vowel, it may lose only a syllable; thus, the word gai (sung) becomes simply an extended ga . But words that end with short vowels may lose two syllables, and so the word pavana (pure, holy) in final position is reduced to pa , drawn out for the requisite number of beats.

The Ramayanis I interviewed could offer no explanation for the peculiarities of the style; the ringing e-ha ! with which each line began was inserted, they said, "just for the rhythm." It is a trademark of the style, however, and a Banaras newspaper article at Dashahra time mentions "the chanting of Narad vani[*] " as a sure sign of the advent of the festive season.[87] One purpose of the melody seems to be smooth transitions between half-verses, as the teams of singers alternate, echolike. The presence of two groups reflects not merely the antiphonal conventions of Manas recitation but also the strenuous nature of the performance style; the alternation provides a much-needed rest.

The other common meters in the text—doha , soratha[*] , and chand —

[87] "Banaras ka gaurav—Ramlila," in Aj , weekly supplement, October 10, 1983, p. 1.

are also rendered antiphonally, but for these the two parties sing alternate lines and there is no distortion of the words. As already noted, the couplets that complete each stanza are particularly well known to devotees, and whenever the Ramayanis sing a doha at Ramlila , a low murmur arises from the surrounding crowd, as listeners softly intone the familiar words. Many regulars carry pocket editions and read along; after the sunset break, the well-equipped nemi produces a flashlight for this purpose. But there are also listeners who know the text well enough to forego books; they sit near the Ramayanis and listen, sometimes nodding approvingly or chiming in on the last few words of a line.

The performance style might best be termed strident—a combination of singing and shouting. Performing without amplification before often-immense crowds, the Ramayanis endeavor to put their message across by sheer lung power, and their effort shows in reddened faces, bulging neck veins, and foreheads beaded with sweat. Maintaining such an effort for four hours a night is no easy task, and the result can hardly be called lilting. Naradvani[*] resembles neither the melodious strains of Manas folk singing nor the reverent drone of the mass-recitation programs. Perhaps this is why some have criticized it as "lacking in beauty."[88] But others, myself included, disagree. The adjectives that always came to my mind were "bardic" and "heroic," and the lusty vigor of the singing seemed appropriate to the occasion: the retelling of the epic of the greatest of all Kshatriyas, sung on a battlefield by a king's own singers. Others clearly share my taste; the brother of a prominent vyas told me almost confidentially one day when we were discussing Katha that even though he had heard all the greatest contemporary expounders, he would, in the last analysis, always prefer simply to hear good Manas recitation, "and the way they do it at the Ramnagar Ramlila is best of all!"

The chief Ramayani in 1982 was Ramji Pandey, who had sung in the pageant for more than forty-five years. A stocky, venerable-looking man, he is employed as a temple priest in the palace and also expounds the epic both within and outside Banaras. He claims to represent the seventh generation of his family to serve in the lila , and he is joined in this work by a younger brother and nephew. Ramji's family has charge of the Vyas Temple on the ramparts of the fort, and a nearby parapet serves him as office-cum-library. A closet-sized room perched high above the Ganga, it is packed from floor to ceiling with Ramayan texts

[88] Awasthi, Ramlila , 83.

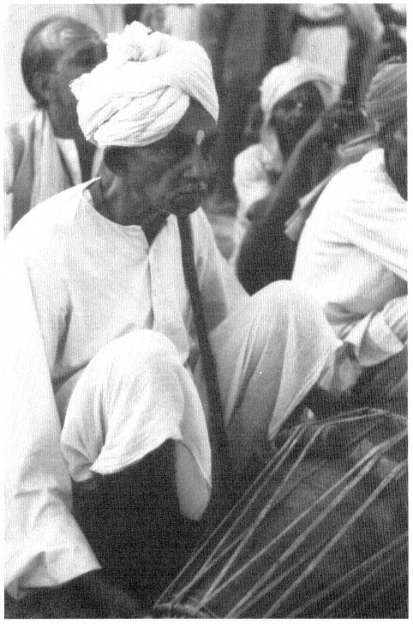

Figure 26.

Ramji Pandey leads the chanting at Ramnagar, 1982

and commentaries, framed photos and posters from Katha programs, and other memorabilia. Also kept here are the cymbals played in the lila and Ramji's turbans—an ordinary one used throughout the cycle and a special one reserved for the enthronement night. Every afternoon during the pageant month, as the sun reddens the sandstone ramparts of the fort, Ramji bathes, puts on clean clothes, and selects the manuscript leaves to be recited from that evening; these are rolled up and placed in metal canisters for transport to the lila site.

The Ramayanis wear brightly colored turbans and ocher Ram-nam sashes; these help them to recognize one another and reassemble quickly when they get separated during treks between sites. They go barefoot, as do the actors, directors, and the majority of audience members; this, they explain, is because they are in the presence of Lord Ram both in the form of the boy actor and in the sacred book they carry—therefore, they show the same reverence they would in a temple. On reaching each site, the Ramayanis quickly seat themselves in a circle; the two singers charged with carrying the manuscript leaves touch the pages to their foreheads and place them atop their canisters. All eyes go to Ramji Pandey, who sits bolt upright, cymbals in hand, looking toward the actors and their directors. Since the reciters sit directly in front of the maharaja, who is mounted on an elephant at the rear of the crowd, they

Figure 27.

Kamlakar Mishra, a village schoolteacher who serves as a Ramayani

at Ramnagar

Figure 28.

Kailash, the aged drummer who accompanied the Ramnagar chanters,

1982

are frequently quite distant from the actors. The success of the performance depends on a clear exchange of signals between Ramayanis and directors (who often cannot hear one another) so that recitation and dialogues unfold in smooth succession and the players mime each action just as the Ramayanis chant its description.

The pace of recitation varies from passage to passage; it is announced by a whispered signal from Ramji, confirmed by the first clang of the cymbals, and immediately picked up by Kailash, the aged drummer who sits on the edge of the circle. Its alternations are not arbitrary but conform to established custom. The evening's recitation always begins slowly but picks up speed during long descriptive passages. However, lines that tradition has singled out as particularly important are intoned slowly and majestically, and occasionally even repeated. Thus, in the opening verses of Aranya[*]kand[*] , when Ram, enthroned on a crystal rock in the forest of Panchvati, adorns Sita with a garland of forest flowers plaited with his own hands—a romantic passage dear to many devotees-each half-line is slowly sung four times while the actors mime the emotion-laden scene, allowing viewers time to savor it.

The Ramnagar staging is characterized by carefully maintained archaisms aimed at preserving the atmosphere of the middle of the nineteenth century, when the pageant attained its f.nal form. The use of handwritten manuscripts is one such convention, for most other productions prefer large-format printed editions, which can be easily read under adverse conditions. The Ramnagar texts, in contrast, run words and verses together in the manner of all manuscripts, but their legibility does not appear to be of prime concern. The Ramayanis pride themselves on their knowledge of the text and rarely "read" from the manuscripts. Seated in a circle, many of them view the sheets only sideways, and while singing tend to keep their eyes on their leader's face. If they glance at the text it is only to note the first word of a line or an approaching break for a dialogue, which is indicated by a red mark on the page. After dark, they are joined by two white-turbaned attendants bearing oil torches—another deliberate archaism—which cast a flickering glow over the scene but hardly improve the visibility of the texts.

Several of the Ramayanis reside in Ramnagar and are in the maharaja's service; the rest come from villages in the surrounding area. Three work as schoolmasters, three more as priests, and one is employed by the local health department. Following Ramji Pandey in seniority is one man who has been singing for more than thirty years and several others whose participation dates back a decade or more. In 1982 the youngest Ramayani—a secondary school student who was much teased

as the "baby" of the group—was in his second year. Whatever their outside careers, the Ramayanis all become, for the duration of the lila , employees of the maharaja, although their remuneration, like that of other participants, is very modest. For approximately forty days of work, each receives less than Rs 50 in cash; a slightly more valuable token is a daily ration of uncooked rice, flour, and pulse, as well as a quarter-liter of milk. In addition, whenever the actors are fed during a scene, portions of the sweets served to them are distributed to the Ramayanis and other cast members as prasad . By these gifts, the maharaja symbolically carries on his ancestors' tradition of maintaining the pageant workers during the course of the cycle.

During the sunset intermission, the Ramayanis take tea and pan —unlike some spectators, they strictly abjure the use of bhang—"Because it brings drowsiness, and then how could we sing?"—and pass the time in conversation, which often runs to lila gossip and Ramayan-related anecdotes. At times they are joined by senior expounders from Banaras, such as Shrinath Mishra and Ramnarayan Shukla, who come to view favorite episodes; these men greet Ramji Pandey affectionately (they are "guru-brothers" through their former teacher, Vijayanand Tripathi) while the younger Ramayanis respectfully touch their feet. The atmosphere is lighthearted and comradely, and the presence of costumed actors milling about can create startling visual juxtapositions, as when several Ramayanis stand chatting casually with Ravan in his full regalia.[89] Like other regular participants, the Ramayanis enter with special intensity into the world of the lila , which colors all their perceptions and blurs the hard boundary between play and life. Ramayan jokes are frequent, but they are only half jokes, because the "other world" is pervasively and tangibly felt. On our first night in Lanka, for example, we were troubled by a horrible stench of putrefaction, which was particularly strong near Ravan's pyramidal citadel at the far end of the field; evidently some animal had died and its carcass was rotting nearby. As we struggled to control our nausea, the Ramayanis discussed the cause of the stench. At last, Ramji Pandey offered the definitive judgment: "After all, brothers, it's Lanka; what else do you expect?" And he quoted a verse from Sundar kand[*] :

Everywhere the wicked demons gorge

on buffaloes, men, cows, donkeys, and goats.

5.3.21

[89] The demon king's role has remained in one Brahman family for four generations. The present actor is highly respected both for his learning and his acting ability and, according to Schechner, is known throughout the year as "King Ravan"; Richard Schechner, personal communication, April 1982.

"The demons devour all these creatures and just toss the bones and half-eaten carcasses here and there. That's why it reeks so."

On the night of kot[*] vidai the ceremony of "farewell to the fort" unique to Ramnagar, the Ramayanis wait with the maharaja in an inner courtyard of the palace for the arrival of the principals, who now come as visiting heads of state. Lakshman himself serves as mahout of the royal elephant, while Hanuman holds the state umbrella over Ram's head. In contrast, the maharaja, who has always been splendidly dressed, wears the costume of a simple householder: a plain dhoti, kurta , and cloth cap. Before the audience of thousands that jams the courtyard, he washes the feet of his guests and serves them an elaborate meal, while the Ramayanis chant from the latter portion of Book Seven—this is purely "background music" to the feast, for the enacted text concluded the preceding day at Rambag with the fifty-first stanza of this book.

When the meal is finished, the boys return to the coronation pavilion to give a final darsan to the crowd. The Ramayanis' work is not yet completed, however, for some sixty stanzas remain to be recited. For this task Ramji Pandey takes up position at one corner of the pavilion with one of the manuscripts cradled in his lap and begins reciting rapidly in a low voice. A few nemis , determined to complete their own parayan[*] recitations, cluster around him, pocket editions in hand. The other Ramayanis simply mill about, waiting for their leader to finish. Shortly before 10:00 P.M. , he slows down and raises his voice; the others gather around him for the final, auspicious verses:

These deeds of the jewel of the Raghus—

one who recites, listens to, or sings them,

effortlessly cleanses the stain of the Dark Age

and of the heart, and enters Ram's abode!

7.130.13,14

On the completion of the final Sanskrit benediction, the little group around Ramji sets up a loud cheer and there are many embraces. The last arti follows immediately, and the Ramlila is over.