3—

Constructing a Woman's Speech:

Sound Film:

Rain (1932)

As we have seen in previous chapters, cinematic representation does not come "ideology free." The visual representation of women in silent film—itself problematic in terms of spectacle and woman as object of the male gaze—is always joined to narrative that brings with it an extended pedigree of literary and dramatic assumptions about woman. Sound technology itself was also fully inscribed within patriarchal ideology, its very invention replete with prescriptions about a speaking woman's "place" typical of its day. As illustrated by Bordwell, Staiger, and Thompson (1985), it was classical sound cinema's goal to find equivalencies in sound to reenforce the ideals of visual cinema as soon as possible. That is why if we are to have any hope of finding a break in the hegemony of classical style (silent or sound), a time when a woman's voice could be her own, we must look closely at a limited period in American film history when the conventions of cinematic representation were for a time in crisis. (Outside of this period, works that constitute a radical break with classical style are restricted to the output of a few brave experimentalists.)

To continue the project begun in the last chapter, the major question to be addressed now is this: "Does the breakdown of established silent film conventions in the transitional period provide gaps in the representation of women that can be read progressively?" To put it another way, to what extent does the dialogization of these modes of representation make it possible to "hear" the voices of women at this historical moment? Does the very struggle to construct new hierarchies between image, dialogue, and sound track make possible, for a moment, the recognition of cinema's efforts simultaneously to represent and contain women and their voices as objects of representation in sound film?

In the transition to sound film, the classical cinematic hierarchy is upset. Rain , directed by Lewis Milestone and produced by Joseph M. Schenck for United Artists, shows the visual discourses of silent film fighting to regain their earlier dominant position, while the theatrical or dialogue-based discourse is simultaneously present and operating at full force. Rain offers us an opportunity to chart the efforts of the transitional period to negotiate a new classical, transparent form for sound film.

The work of the text is everywhere apparent in Rain in the play between insufficiency and excess. By varying from previously set norms defined by the conventions of silent film, the excessive quality of the camera work and the insufficiency of preparation in the editing (leading to jarring cuts, "unmotivated" camera moves, "odd" angles, etc.) stand out and declare their enunciative function. Conventions that had become naturalized in the earlier cinematic hierarchy are altered or abandoned.

In the transition to sound film, new conventions had to be established in full view of the audience. A possible cause for the cinematic institution's tolerance of such visible disarray can be seen in the industry's need to continue churning out product despite the fact that conventions for the construction of sound/image narratives had not yet been fixed. Seen in this light, Rain 's status as an adaptation of a play, a short story, and a remake of a silent film becomes not just a pedigree but a strategy. In order to maintain the necessary level of popular intelligibility, Rain and the many other remakes and adaptations of the era summon earlier forms to shore up their ability to signify and to stave off the fragmentation caused by attempts to incorporate sound.

Julia Kristeva argues that a "dynamic notion of reading as a relationship between reader and text . . . implies that no texts, 'mainstream' or otherwise, bear specific a priori meanings in and for themselves" (Kristeva 1980, p. 12). At its most fragmented, Rain illustrates a cinematic version of the centrifugal forces of "dialogized heteroglossia" (Bakhtin 1981, p. 273) where languages (here systems of signification) are flung away from a center, their differences emphasized as chances of mutual recognition and cooperation become more and more remote. Because of its very stylistic inconsistency, Rain is an ideal text to indicate the range of experimentation conducted before the classical style was recovered and reconstituted. The value of a text like Rain lies precisely in its struggle, its revelation of the historical determinations that influence the preference for a given signifying system over another in a given period, here made clear in the comparison of the silent and sound versions.

Because of the primacy of the struggle to form a new classical style that would "invisibly" incorporate sound, women in sound film could not be inserted directly back into the roles and styles of representation conventionalized in silent film. The examination of "woman and her voice" in cinema thus requires a combination of formal analysis of the use of sound and a feminist analysis of representation. My analysis of Rain will thus alternate shot-by-shot close textual analysis with summaries of scenes. The major part

of the analysis corresponds to the first act of the play and four other scenes or sequences I find illuminating on the subject of woman and/or her voice. This is an admittedly arbitrary approach, and in its defense I can only cite Roland Barthes: "The text, in its mass, is comparable to a sky, at once flat and smooth, deep, without edges and without landmarks . . . The commentator traces through the text certain zones of reading, in order to observe therein the migration of meanings, the outcropping of codes, the passage of citations" (Barthes 1974, p. 14).[1]

Another methodological issue worth noting is the separation of the film text in terms of shots. The shot is a measurement applicable solely to the image track. It has been a point of sound editing to overlap the cut (see Doane's "Ideology and the Practice of Sound Editing and Mixing" in Weis and Belton 1985).[2] Music has also traditionally been used to smooth transitions between shots and scenes with sound effects acting as a binder of spatial and temporal continuity within a scene. As providing a seamless flow of sound has been one of the strongest principles of sound editors, using the shot as a marker disregards the true entry and exit point of sounds. Nevertheless, using shots as markers does allow a practical breaking point to which the ebb and flow of sounds can be referred, therefore it will be retained—with these reservations—in the shot-by-shot sections of the analysis.

Because 1932 is rather late for an "early" sound film, Rain also defines itself in relation to the earliest sound films. This is especially noticeable in mostly negative ways, primarily in an almost compulsive urge to move the camera in order to avoid presenting a great deal of dialogue from a static camera position. In terms of discussing the contribution of sound and the conveyance of narrative information during a long take, the beginning and the end of a shot become virtually useless as reference points. Sounds begin and end somewhere in the middle of a take, some takes in Rain lasting as long as six minutes. In those instances, we shall need to propose new sound and dialogue-based methods for analyzing the content of a shot, redefining a shot as an audio/visual unit.

The importance of the long take in the representation of women is one that I do not think has been addressed. In the long takes as used in Rain it initially seems not only possible but probable that women speaking synchronized dialogue while walking side by side with men in a continuous take are at last equal holders of cinematic space. Whether or not that turns out to be the case is one of the key questions this analysis will seek to answer.

Introductory Montage and the Opening Scene

The opening minutes of the film, made up of roughly three segments, introduce a competition among signifying systems culminating in the dramatic entrance of the figure of the woman, Sadie Thompson. In the opening mon-

tage, the silent film hierarchy appears to have been lifted whole from an earlier era. We see clouds moving overhead. A drop falls in a puddle and ripples form. Another drop falls in the sand on a beach with shells lying around. Drops splash on the diagonal lines formed by boards. The clouds continue to mass.

As the montage of rain falling on various surfaces proceeds, we hear the symphonic score from the titles. Except during the titles and credits, Rain uses all forms of music sparingly. During the "rain montage" there is no attempt at synchronous sound effects.

Throughout the course of the film these tropical montages (all strongly reminiscent of Flaherty's Moana [1926]) will reappear at specific points. What might be called the (silent-) cinematic discourse is consistently summoned to oppose the emergence of the theatrical discourse at its strongest. At the ends of acts 1 and 2, each clearly preserved, the camera pulls back, revealing the set as a set, the actors pronouncing famous lines, and an approximation of the proscenium appears at the top of the frame. Such obtrusive theatricality is immediately contradicted by the outdoorsiness of sunrises, natives hauling in nets, montage-style editing versus camera movement, asynchronous singing and symphonic music versus the careful sync and formalism of the acting in the preceding scene.

In the opening scenes, however, the silent-style montage leads effortlessly into a flawless example of what was to become the classical hierarchy of sound film. As a close-up of a rain barrel dissolves into a long shot of a rain-swept, muddy path, the sound of falling rain gradually rises on the sound track. The score fades away. After a moment we hear men singing. It is impossible at first to determine whether or not their voices are part of the physical space "offscreen" or non-diegetic. Aurally, the singing is a little lower than the volume of the rain, which helps place it "in" rather than "under" the scene as well as giving it a quality of distance in relation to the image. When a group of soldiers marches into the frame from behind the camera, the spatial depth added to the image by sound effects and offscreen voices is emphasized.

The soldiers sing about being tricked into the Marine Corps with promises of paradisiacal islands as we see them marching in the mud and rain. Unlike in silent films such as The Big Parade (1926) where title cards with musical notes drawn on them are intercut with close-ups of various soldiers "singing" as they march, the sound film doesn't have to construct the "effect" of singing. Instead, sound allows for continuous spatial and temporal progress while the ironic commentary is built in, the counterpoint between the two registers contained within one shot.

Tracking shots alternate close-ups of individual singers with shots of boots marching, intercut with long shots that replay the question of diegetic versus non-diegetic sound. Once more we see an unidentified gray exterior of rain-beaten palm trees, held a couple of beats before the men appear. As the ma-

rines enter the frame, the camera begins to track right, framing them through the horizontal slats of a fence. As they come to a halt at the end of the song, a sergeant gives an order. Two men step out of line and join him. They begin the dialogue. In a striking shot in depth, we see a large ship in the distance (the subject of their conversation) and hear its horn. The three marines reverse direction and the camera tracks left to follow them.

The aural balance of the sound track, between the song and the continuing rain, the fading of the rain as the dialogue begins, and the visual balance of having the characters "lead" the camera in order to diegetically motivate the camera movement all give the effect of a much later period and are in fact reminiscent of John Ford and Raoul Walsh service films of the late 1930s. The long take and moving shot exalt the image while allowing for uncut sound and a rather complicated sound mix. The human figures are placed in an audio and a visual continuum, the foregrounding of the action classically effacing the enunciation.

In another nice integration of silent and sound techniques, the marines announce they are going to fetch the local store-owner, Horn (Guy Kibbee) and take him to the ship we see in the distance. With the mention of Horn, we cut to a sign identifying Horn's "General Store." The camera smoothly tilts down from the sign to reveal the veranda of a tropical inn and, in an effect of depth, a child running out of the store toward the camera. The child falls and cries, and a large woman in tropical dress lumbers after it, scolding. She bends over to pick up the boy and falls herself. The marines, bringing with them their characteristic camera movement, lift the child up and hoist Ameena (Mary Shaw) onto a chair. Ameena and Sergeant O'Hara (William Gargan) in a medium long shot joke about her husband Horn. The other marines carry Horn out as the camera dollies back to accommodate them. Throughout the scene, camera movement and stasis alternate fluidly while the dialogue unself-consciously establishes character and short-term narrative goals that link the island's inhabitants with the ship.

However, this classical sound style effortlessly sets up a cruel joke on the text's "other" woman. A large woman with long black hair and a prominent mole on her cheek, Ameena's appearance contradicts Hollywood and European standards of glamour. As a half-asleep Horn is carted onto the veranda, he drunkenly asks where he is. In an extreme close-up, Ameena turns to face the camera and answers, "Home." The "joke" rests on our deducing that his wife's appearance is the direct cause of Horn's drunken lethargy: "If that was my wife. . . ." As an insert in the midst of fluid tracking and long shots, the close-up stands out, bearing the unspoken weight of several kinds of prejudice. Exhibited for our derision as a South Sea islander, but more particularly as a woman, Ameena is nailed on looks. The flawless integration of sound and image shows how woman can be positioned as the center of a scene while ruthlessly excluded as its subject. (When the film was edited to seventy-seven

minutes, presumably in order to fit a double bill, the character of Ameena was cut almost entirely.) This pattern of woman as disruption will be repeated for the next two women we meet and will find its most elaborate expression in the introduction of Sadie.

What is perhaps most striking about Rain as a text is that once it has achieved what will become the "correct" balance between image, camera movement, and the layers of the sound track, it promptly abandons this hierarchy and continues to experiment with different possible hierarchies between sound, dialogue, and image. It is the lack of any sense of progress from scene to scene that lends Rain its archaic quality, exposing its bricolage of old and new conventions.

The hybrid nature of the earliest attempts to join sound and image is most readily apparent in the partial talkies of the late twenties, especially in films with silent dramatic scenes and interjected musical numbers. However the continuing hybrid nature of later transitional films is less well noted. Bakhtin defines the function of hybridization in the novel as "a mixture of two social languages within the limits of a single utterance, an encounter, within the arena of an utterance, between two different linguistic consciousnesses, separated from one another by an epoch, by social differentiation or by some other factor." Although Bakhtin feels that it must be conscious and intentionally done in order to be artistically significant in the novel, he adds that even "unintentional, unconscious hybridization is one of the most important modes in the historical life and evolution of all languages. We may even say that language and languages change historically primarily by means of hybridization" (Bakhtin 1981, p. 358).

Both of the director Lewis Milestone's earlier, and notably successful, sound films were equally hybrid in construction. All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), which was seen as an early model for reclaiming the "cinematic" from the staginess of other films of the period, did so through the use of silently filmed and edited scenes with non-synchronous sound tracks applied over them. The Front Page (1931) forfeited the location montage of the earlier film in favor of a constantly moving camera and the rapid-fire dialogue and dramatic construction of the theatrical adaptation. However, both of these films exhibit internally consistent rules, something remarkably absent in Rain . By 1932 the half-measures of the earlier films were being rejected in favor of a search for a stable hierarchy of the relation of image to dialogue to sound that could be employed in all scenes with the transparency of enunciation typical of silent narratives.

Rain 's sudden breakdown of any consistently employed system of signification cannot be attributed to simple incompetence on the part of the director (as he managed the "correct" construction in one scene and would again in later ones) or to difficulties with the primitive technology. By this time many sound films with more "advanced" and consistently employed conven-

tions for binding sound and image had already appeared—for example, Blackmail (1929), Applause (1929), M (1930), and The Blue Angel (1930). The "proper" hierarchy of the marching scene and others proves that Milestone (using the director's name as shorthand for the industrial, technological, and cultural struggles rampant in all films of the period) knew how to organize the various registers of sound film. What the unpredictable and unconventionalized experimentation in other scenes suggests is that this particular hierarchy was not yet privileged. Bordwell, Staiger, and Thompson describe the philosophy that determined the eventual canonization of a certain hierarchy of registers in what they term the "image-sound analogy," where "the recording of speech is modeled upon the way cinematography records visible material and the treatment of music and sound effects is modeled upon the editing and laboratory work applied to the visual track" (1985, p. 301). Rain shows the range of possibilities still being juggled in 1932.

The Ship

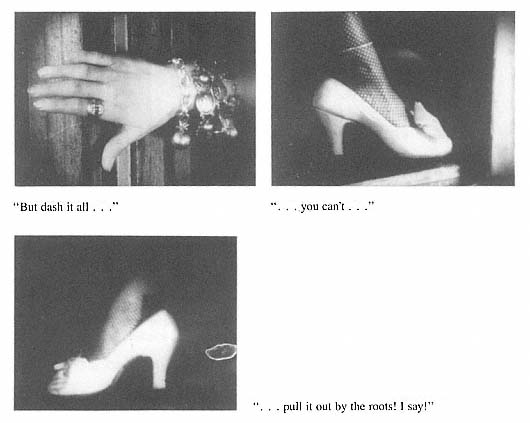

After the marines march away with Horn, there is a cut to the interior of a cruise ship. On several visual planes, we see passengers dressed in 1920s clothes standing in line and we hear tinny music, "crowd noises" made up of murmuring voices and laughter, and pursers calling, "Have your passports ready, please." We cut to a close-up of a handbag as a woman's hands search through it and take out a passport. She extends the passport (with the word Passport written on it) directly toward the camera. A man's hand enters from the lower portion of the frame and takes it. The camera tilts down as if in a point-of-view shot and reads the name on the card as the man points with a pencil "Mrs. . . . Robert . . . Macphail." On the sound track we hear a woman's voice: "Let me see. You want my passport, don't you?" As the customs agent points to her name, the woman's voice continues: "My husband and I usually use the same passport. We have separate ones this time, in case I should wish to visit the other islands while he's working."

The use of voice-over combined with a close-up of a card with the character's name on it is a hybrid of filmic conventions from two different periods combined in a single shot. In the silent film Sadie Thompson , the characters are introduced in a strikingly similar manner. A sailor approaches Dr. Macphail and Mr. and Mrs. Davidson and requests that they sign his "travel diary." Each writes something "characteristic," which we read (Davidson about evil, Macphail about tolerance) and signs his or her name. In this way, their personalities are directly linked to their names while avoiding the use of an overt and disruptive title card. In Rain , it is the voice that is first linked to the name through sound film's ability to let us hear the character speak while showing us something else.

At the end of the passport shot there is a dramatic swish pan to the right. In

a medium shot we see a young woman standing across a table from a customs agent. The use of the swish pan as a transition is one of the oddest choices made in the film and illustrates a breakdown within the image system due to an overreliance on the sound track. The continuity of voice (from the woman speaking about joint passports to this woman's speech about the rain) does not sufficiently establish that the figure we see is the same woman who stood directly in front of the camera in the previous shot. Not knowing to what extent sound could be depended upon to convey a sense of spatial continuity to the audience, the image system neglects some of its earlier rules for creating a coherent space in favor of confusing experimentation.

A swish pan (also known as a zip pan or a flash pan) automatically implies directionality. The image within the pan is blurred, but the streaks move in a specific direction. The camera's tile in the earlier shot indicated that we were facing Mrs. Macphail, and that it needed only to tilt back up to locate the speaker, consequently the sudden pan to the right to a woman standing silent disorients us. If it is the same woman, she has suddenly moved several feet in space with no visual or audio indication of it (such as her hands moving out of the shot or a voice saying, "Step to your right, please.") The change in screen position of the customs agent is similarly puzzling. His hands were directly in front of the camera, as in a classical point-of-view shot, and now we pan right and find him in effect sitting next to himself. The dissection of character into name (conveyed by graphics), voice-type (male/female, mellifluous/grating, intelligent/foolish), and image (hands/body) contributes to the incoherence of character identification.

Throughout Rain , examples of similarly confusing constructions will be traceable to this play between insufficiency and excess. In the original establishing shot of the interior of the ship, close examination of the crowded shot shows two customs agents sitting side by side. Mrs. Macphail, chatting away, has in fact moved from her original position in front of the first agent (and the camera) to the position we discover her in, standing before the second man. Her movement, like the second customs agent's receiving the passport, occurs offscreen. The second time we see this shot sequence (for the introduction of Mrs. Davidson), the first customs agent clearly hands the passport offscreen to someone on his right.

Although the image seems to depend on the sound track for connecting the passport shot to the shot following the swish pan, it refuses to let dialogue carry simple narrative information such as the name of the characters. It would be simpler and quicker to have the woman look into the camera as she hands over her passport and say, "I'm Mrs. Macphail." However the visual construction of graphics, pan, then image—at the same time more insistent and more confusing—maintains the precedence of the image and of silent film conventions for character identification, while sound is relegated to background filigree or to a function it cannot easily perform (connecting characters

in space regardless of the work of the image). This formula for introducing characters, though time-consuming and cumbersome, will be followed for Mrs. Macphail, Mrs. Davidson, Dr. Macphail, and Mr. Davidson, with little elision.

David Wills suggests that "excess, finally, is always about the means or economy by which the Same accommodates, appropriates, or represses the Other; by which difference is and isn't," (1986, p. 35) and this construction not only points to the conflict between image-systems and sound but, fittingly, to the representation of the women. The smoothly flowing opening scenes on the island are interrupted by the fragmented, chaotic world onboard the ship, a disorganized, disconnected place to which we are incoherently introduced by two women.

Despite the fact that she is the first character introduced, Mrs. Macphail doesn't have any character. She mindlessly parrots the other characters' prejudices. Her dialogue can be accurately described as foolish prattle; even the nearly unidentified character of the customs agent is allowed in effect to have the last word in their exchange. She gazes into the distance and muses, "I wonder why it should rain. Doesn't it ever stop?" The officer responds "Yes, ma'am?" as if he purposely hasn't been listening. Insulted and confused, Mrs. Macphail takes her passport and turns away.

In her series of introductory shots, Mrs. Davidson (Beulah Bondi) is effectively introduced as a rude, inconsiderate woman, as well as an inefficient one who criticizes others for what the image reveals are her own failings. When we see the second woman's hands (Mrs. Davidson's), we see the customs man's hand reach in and wait for the passport. A woman's high voice states, "A little more efficiency and we wouldn't be kept waiting so long," as she fiddles with her purse. Here the film does take advantage of the asynchronization of shot and sound track, ironically contradicting her words with the cultural stereotype about women and their messy purses.

Mrs. Davidson also allows the text to make use of stereotypes associated with women's voices. Before we see her, her shrill and monotonous voice is defining her as unattractive and prudish. Mrs. Davidson's voice type was established in Maugham's original story. "The most remarkable thing about her was her voice, high metallic, and without inflection; it fell on the ear with a hard monotony, irritating to the nerves like the pitiless clamour of the pneumatic drill" (Maugham 1967, pp. 413–14). When we see her, it is not surprising to find her a middle-aged woman wearing a floppy, shapeless hat and glasses. She stands adjusting her hair as the agent waits, holding her passport out to her. She makes no move to take it, saying officiously, "Thank you, just put it down, please."

In contrast, the introduction of Dr. Macphail is neat and quick. We begin immediately with the name-bearing card in the agent's hand, pointing to the name "Dr. Macphail." Macphail addresses the men by their proper titles

("By the way, officer . . .") and they exchange "witty" repartee about the islands (as opposed to the curt dismissal of Mrs. Macphail), establishing the men as equals. The issue of pronunciation is also introduced, in its own way calling attention to the possible contradiction between image and sound track. "Pago Pago" which we see written on the passport cards is pronounced "Ponga Ponga." In story, theater, or silent film, this apparent discrepancy would not be an issue. Here it is demonstrated and unexplained.

When Davidson is introduced, there is no small talk. The card reads "Mr. Alfred Davidson." After the swish pan, the officer says, "Welcome to Pago Pago, Mr. Davidson," the first exchange that allows a character to be identified aurally as well as graphically. Davidson's voice is culturally identified as being typical of a minister, while the "Mr." on his passport and in the dialogue insists on his unaffiliated status. Nevertheless, his voice, posture, bow tie, and careful enunciation define him as a preacher. (Maugham also mentions Davidson's "deep, ringing voice" [1967, p. 422].) Shortly afterward, when he informs the others that a quarantine will keep them on the island, Walter Huston's enunciation of the line, "It may mean a delay of several days," complete with the rhyme of "may," "delay" and "days," and the elongation of "sev-eral" calls attention to Davidson's oratorical expertise and is the sort of elocutionary bravura that identifies a nineteenth-century public speaker.

After Davidson is introduced, the text undergoes a crisis in point of view. In the background, framed by Davidson and the customs agent, a man dressed in white ascends a dark, curving staircase spanned by an arch. As he reaches the top, we can just see his legs turn left as he exits the frame and his partial reflection comes into view in a mirror on the right of the stairs. This begins a series of looks that will float around a confused, insufficiently established space.

Mrs. Davidson (who has mounted the stairs during Macphail's introduction) turns and looks down. Mr. Davidson says, "Thank you" and goes to the stairs. As Mrs. Davidson begins down the stairs, walking toward the right of the frame, the camera pans with her. However, as the camera pans horizontally, Mrs. Davidson moves progressively downward and disappears from the bottom of the frame. The pan continues without a subject until it rests on the mirrored wall behind the back of Mrs. Davidson's head. Mr. Davidson's reflection enters this odd two-shot from the right. Dr. Macphail in a low angle shot approaches a railing and looks down to the left. Already, his position in space is impossible to fix. According to the layout of the ship, as will eventually become clear, Macphail is on the right at the top of the stairs, despite the fact that we saw him turn to the left earlier. If he is on the right, though, his gaze is not at the mirrored shot presented to the audience but at the physical figures of Mr. and Mrs. Davidson, which remain unrepresented—we never see them occupy the space Macphail is seeing. As Davidson reaches the top of the stairs to announce their quarantine on the island, there is a reaction

shot of Macphail standing on the left of the stairs, looking at Davidson screen right. This shot would require an offscreen shift in position as insufficiently indicated as that of Mrs. Macphail during the passport scene.

When all of the characters are standing at the top of the stairs in a small waiting room, the text recreates one of the static long takes for which early sound cinema was rightly or wrongly notorious. This shot's tribute to sound lies in its conceding major narrative information for the first time to the verbal discourse. As the camera looks on from a distance, the characters stand around, their bodies artificially posed facing the camera. Davidson, the principal speaker, stands with his back to the camera so that even the visual pleasure of reading lips (so salient in silent film close-ups) is lost, leaving only the recognition of his voice to tell us "who is speaking." Even this shot, however, leads to a breakdown in visual point of view. We see a shot of men marching past an open window. Davidson, his back turned to the camera, says, "There's Mr. Horn now." There is a repeat of the previous shot (a literal demonstration of déjà vu) and this time we see Horn pass. Contradicting the silent film convention of having a look key a cut to a subjective point-of-view shot, here Davidson's look is completely unrepresented visually because his back is turned. It is only the dialogue that tells us he has seen something and retroactively authorizes the first shot through the window. At the end of the scene, Davidson leaves the group and Macphail turns to watch him go. The cut to a close-up of Macphail is a mistake in cutting continuity, jumping stage line 180 degrees, from Macphail's back to his face, in order to accommodate his look.

The reason the text doesn't completely fall apart is to a great extent because the sound functions as a backup system, binding together this highly problematic series of cuts. Despite visual fragmentation, the dialogue flows, exchanged by characters as if they were in a coherent space, maintaining a minimum of intelligibility at the narrative level. The continuation of the same sound effects at a stable volume among these shots connects them in space and time even if it cannot specify where the characters are in relation to each other or maintain consistency in their relation to the camera.

The above breakdown of rules governing the image alerts us to an uncertainty about how sound functions in relation to the image. The consistency of sound effects from shot to shot within a scene is followed throughout Rain even though, as the scene above shows, it is not sufficient to make up for visual incoherence. The sound track's "coherence of causality, space, and time" (Bordwell, Staiger, and Thompson 1985, p. 304) seemed to offer the filmmakers at this moment in history the chance to free the image system from its obedience to those same principles. Milestone et al. did not "forget" classical rules of construction; they merely abandoned them, feeling—wrongly—that other methods, specifically sound track construction, would serve as well. We see in this the indication of a potential and radical break with classical paradigms, provoked and made possible by sound.

The text immediately compensates for the confused editing of these scenes by restoring the absolute coincidence of sound and image in another uncut traveling shot of Horn and the marines as they stroll along the outside deck discussing Davidson. Such bravura tracking movements provide the reassurance of unqualified spatial and temporal continuity both aurally and visually. The result is a form of realism more technical than dramatic, synchronization displayed as an end in itself. Compared with the preceding scene, the camera's movement stands as a signifier of the "cinematic" (versus the theatrical or early sound film style). It also reenforces the presentation of the marines as a liberating force.

The dialogue between Horn and Sergeant O'Hara establishes Davidson as not a missionary while speaking strictly in terms that refer to missionaries: "They'll break your back to save your soul." Instead, Davidson becomes a "professional reformer" with the presumably civilian/political post of "investigator of navy conditions." The political is excised with the next line—"He wields more influence in the South Seas than the sun, the planets, and the American government"—leaving Davidson as an independent operator rather than the representative of either church or party.

As the camera dollies back to keep the group at a constant distance, the sound of music and voices below deck, so prominent early in the scene/shot, is left behind. The "tinny" ragtime, which had been loudest in the first establishing shot of the ship's interior, then quieter at the top of the stairs and barely heard on the walkway, provides an aural transition that maintains the spatial relationship of each setting to the previous one. As the marines march on, they again supply a diegetic source of music, singing, "The worst is yet to come, the worst is yet to come." A muted horn mockingly underscores them as jazz intrudes on the sound track and threatens to drown them out. The camera stops in its tracks as a body comes flying out of a doorway and lands at the feet of the marines.

The conflicting musical discourses are a powerful auditory introduction to a new force within the narrative. The jazz theme's relationship to the image is once more difficult to determine. The competition in volume between the singing (initially louder) and the jazz (ultimately louder) suggests it is diegetic, however "movie music" could serve the same function just as easily. After all, the marines never register any awareness of it—it is the dramatic entrance of Bates, the ship's quartermaster, that gets their attention. In this scene the source of the music is insufficiently delineated and it is only the period's and the rest of the film's hesitance to use non-diegetic music that mitigates the assumption that this is standard or classical background music.

Historically, Rain occupies a position halfway between the earliest sound films' painstaking accounting for any sound on the track and classical sound film's use of the wash of the non-diegetic score. The indeterminacy of the music on the sound track (the low volume of the ragtime, the half-hearted visual

presentation of possible sources) is part of the transitional phase. A cause is supplied for nearly all of the music in the text, but it is not stressed. When Macphail looks down from the top of the stairs at the Davidsons, there is a loudspeaker in the corner of the frame that could be playing the music on the ship. After we meet Sadie and enter her cabin, we see a phonograph that may or may not have been playing the jazz we heard.

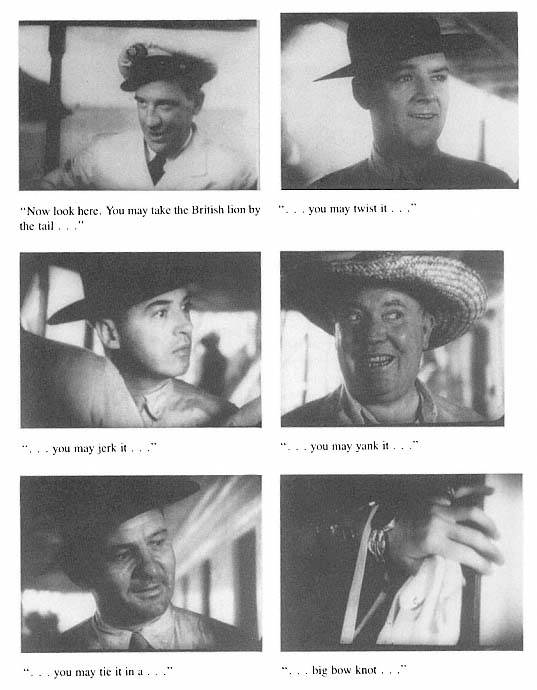

The introduction of Sadie demonstrates what will become the classical way to create and maintain a space by tying together a montage of looks with over-lapping dialogue, voice-over, and background music—a style, as we shall see, with particular implications for the representation of women. A shot-by-shot description will show the close coordination of the various parts working together rather than at odds. As Bates's exaggerated motto about the British lion (spoken with a pronounced British accent) continues, an enigma is established regarding what it is everyone sees that (a) has the power to excite them all, (b) has the strength to throw Bates out on his tail, (c) presents such a threat to imperial masculine power (a castrating woman?), and (d) is related to that music.

Shot 1: Bates pushes his hat back. "Now look here. You may take the British lion by the tail—"

Shot 2: O'Hara smiles (at Bates) then suddenly turns his head to the right. Bates in voice-over: "—you may twist it—"

Shot 3: Second marine quickly looks right. Bates: "—you may jerk it—"

Shot 4: Horn grins and slyly looks to the side and mouths "Oh!" Bates: "—you may yank it—"

Shot 5: Third marine looking right smiles and looks appraisingly up and down. Bates: "—you may tie it in a—"

Shot 6: A heavily jewelled hand reaches into the frame and grips the side of the doorway. Bates: "—big bow knot—"

Shot 7: Another jewelled hand, the left one, reaches out to the other side of the door. Bates: "But dash it all—"

Shot 8: A foot wearing mesh stockings and a shoe with a big bow on it steps into the frame and touches the floor. Bates: "—you can't—"

Shot 9: The other foot steps into the shot and steps down beside the first. As the music plays, the woman turns her ankle on the beat, giving the impression of dancing. Bates: "—pull it out by the roots! I say!"

Sadie's entrance is in terms of metonymy in the image and on the sound track. Her jewelled hands and stockings all stand in for the prostitute as "fancy woman," "vulgar" and excessive. The montage in itself is an excess,

fragmenting the woman's body, taking her apart in a way that correlates to the looks of the men in the previous montage. The major project of the film will be the task of reconstituting Sadie as a "whole" woman, something that can, according to the values of the narrative, only be achieved through marriage. Sadie needs to be turned from spectacle into subject, but a subject who is ultimately positioned firmly within patriarchal terms. The question of the woman's body is at the heart of the text: the conflict between Sadie and Davidson, which reaches its climax offstage and offscreen and reduces (or epitomizes) their conflict as a sexual one. Sadie, as a representative of opposition to the dominant order, is most disruptive not as a member of an exploited subclass but as a woman.

Although the narrative resolves the "problem" of the sexual woman through the recuperation of Sadie into marriage, the condition of the text itself allows it to be interrogated from a feminist perspective. Sadie's oppositional stance in dialogue, voice, posture, dress, and so on, infiltrates the codes of editing, helping the spectator read them for what they are, and revealing the fragmentation of the woman in response to the male gaze. Annette Kuhn,

summarizing theories of a "feminine text" (those of Kristeva and Hélène Cixous in particular), locates exactly this sort of decentered spectator position as central to a potential feminist/feminine art.

The feminine text would disrupt, challenge, question and put its reader-subjects into process. In providing a challenge to situations in which the process of signification is not foregrounded, as is the case—it is argued—in dominant texts, in masculine discourse, the feminine would be subversive of such discourse, would constitute a disturbance to dominant modes of representation and thus to the dominant cultural order.

(Kuhn 1982, p. 13)

As a partially open text—that is to say, one that is for many reasons unable to provide the transparent signification of the traditional classical text—Rain enables the reader/viewer to take a more consciously active position toward constructing meaning and repositions the spectator/auditor as a producer instead of a consumer. Its processes of signification are revealed through excess and through insufficiently instituting the new conventions of the emerging classical sound film.

Shot 10: The climax of the "Sadie montage" is an empty frame. After a pause, Sadie leans into the frame. She wears a feathered hat, a huge necklace and smokes a cigarette. Bates offscreen: "—can't you take a joke?" We hear the men laughing. Sadie does not smile. The music again reaches the "wah wah" muted trumpet phrase as Sadie's face remains immobile, low in the frame. Bates: "Hello, lads!"

As Wills points out in connection with Godard's Prenom: Carmen , "The figure of the woman is obliged to bear the internal contradictions of a system in crisis" (1986, p. 33). In the first shot of Sadie, she has no voice and is defined in relation to the hierarchy of silent cinema—the image and music.

She is her image, defiantly made up of parts, and "her" music. Each gives her some control while always placing her in a negotiated position in relation to the hostility of language. She can turn the music on or off (late in the film this will be a point of conflict with O'Hara) just as she chooses her extravagant costume. At the same time, the music that substitutes for her voice serves as commentary on the text, typing her. We do not yet know whether Sadie is playing her gramophone, leaving the music to be read as the text's, a point of view distanced from Sadie's. And although Sadie might choose her clothes, she has no control over the montage that fractures her image. She is fetishized by the fragmenting visuals and the music, which distills her "essence" into a blues number.

The relation of woman and montage has been well examined by feminists (Kuhn, Mulvey, Johnston, Bergstrom et al.), but the relationship of the woman to music is equally complex. "Sadie's music" is fetishized and as such can stand in for her. Wills addresses this audio/visual interaction, arguing that through music "the economy of representation is both articulated and disrupted": music "provides a difference against which the visual can define itself while at the same time participating with the visual in the same field of possible representations" (ibid., p. 42). I would argue that music and image are not in the "same field," however, as we see here in Rain . The music can be harnessed to serve the same narrative and cultural function within the text that the image does. Nevertheless the woman's relation to the music is quickly problematized as Sadie moves to assert her will through control of the apparatus. Even in this first scene, there is an excess in the music, a quality that exceeds the narrative and the image and that cannot simply be read as approval or deprecation. The jazz number has connotations of sex and heat ("low-down" and "dirty") and carries jazz's affiliation with a black culture here stereotyped as being closer to "animal instincts" than the repressed middle-class Protestant culture represented by Davidson and the Macphails. Acoustically, the most recognizable motif in the instrumental number is a muted trumpet announcing itself with a "wah wah wahhh."

The energy and also the volume of the music give it a rush that's invigorating after the downbeat symphonic opening music or the inconsequential tune played under the passport scene. This is not to put forward an audio essentialism (sound as automatically "more" than the image in some kind of transcendent way); what I am trying to avoid is the assumption of an image/sound analogy or of sound as always an image-function substitute (see Bordwell, Staiger, and Thompson 1985, pp. 301-4, and Metz 1985, pp. 154-61). Even when fitted into the pattern of image-system functions from silent film, sound (music, voice, effects) exceeds its function and model.

Bates addresses the marines, saying, "Boys, I want you to meet Thompson. Sadie, meet the boys!" We cut to a medium long shot of Sadie from head to waist as she leans against the doorjamb, her left arm extended out to the other side. She smiles ruefully and gives a small salute: "Boys."

Crawford's voice is very low on her first line, approximating the husky or hoarse quality Maugham describes, and at odds with the high "feminine" voices of Mrs. Macphail and Mrs. Davidson. Such a low voice contrasted with the exaggerated femininity of appearance (jewels, hat, heels) suggests androgyny. As Richard Dyer hypothesizes in Stars , the star's persona works to reconcile various cultural contradictions.[3] These are worked out both in the narrative and in the space between image and voice. Many female stars of the 1930s are fetishized for their low voices, a trait combined with a tendency to portray characters with masculine as well as feminine traits (and clothes). Dietrich (especially when singing), Crawford later in the decade, Garbo (Anna Christie, Queen Christina ), Lauren Bacall in To Have and Have Not —all sported glamorous, ambiguous images and low voices noted by critics and fans.

While low voices were particularly apt for fetishizing, and thus controlling, the always potentially disruptive representation of women, high-pitched "feminine" voices were frequently caricatured as suitable for comic parts (Betty Boop, squeaky "baby doll" voices) or, as with Mrs. Davidson, for puritanical "battle-axes." Certain technological innovations during the 1930s were seen as improving the recording of women's voices, which had been considered "problematic" and even inadequate for the recording apparatus. Crawford's voice is not only low, but it also is the sort of "faceless" voice, lacking distinguishing characteristics such as an accent, that was favored by Hollywood at this time (Marie 1980, esp. p. 221 n.3).

Later, when the Davidsons and the Macphails are gathered in the main room of the inn, we are again made aware of the connection between Sadie and music. Sadie has already had a set-to with Mrs. Davidson over some wild dancing on the Sabbath, presented in a dizzying 360-degree pan. As Davidson sets forth a "program of recreation" for their forced stay on the island, we hear "The Wabash Blues" start up in a room offscreen. Mrs. Davidson explains that Sadie is a common woman who was also on the ship and will be staying at the inn with them. As the music plays loudly, Davidson shows signs of distraction.

Thematically, the music acts as a signifier of Sadie's sexuality and is her power to disrupt. Her sexuality is the disruption of the patriarchal authority established to contain it. The music broadcasts to everyone within hearing that she is available and not contained. Unlike her voice, which fades in and out depending on whether the men in the room are talking, the music has a constant presence, floating through all the conversations and beyond the confines of its immediate geographic setting. Davidson is so keenly aware of her presence, through the music, that he can't concentrate. Here Sadie begins to assert control of the music on the film's sound track. Whether or not she can play it becomes the original conflict between her and Davidson, and upon being freed from his control, she returns to the music, brazen and loud. Only when she is

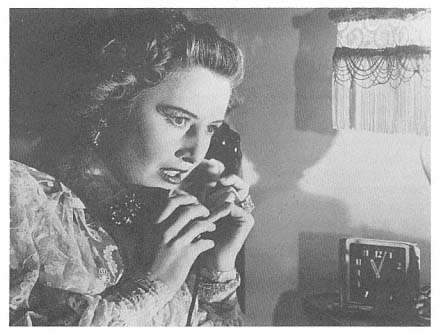

Woman and sound technology in silent film ( Sadie Thompson )

about to accept the marriage proposal from O'Hara does she agree to turn it off.

As it does in both the play and the short story, Davidson's fight with the marines in Sadie's room takes place "offstage." As such, it marks a return to theatrical discourse. Sitting with his wife and the Macphails, Davidson suddenly proclaims, "She's out of Iwelei!" (pronounced "evil lay," the text's code word for the red-light district of Honolulu) and storms "off" into Sadie's room. We hear the scuffle between Davidson and the marines and hear the needle being dragged off the record. The music stops and Davidson is thrown out back into the image/set.

Humiliated after the scuffle, Davidson exits by walking slowly up the long flight of stairs against the back wall. Mrs. Macphail asks Mrs. Davidson what Mr. Davidson is going to do. Mrs. Davidson, standing on the stairs, announces portentously, "I don't know what he'll do. But I wouldn't be in that girl's shoes for anything in the world." The camera pulls back to reveal the entire set. The Ordoona 's horn sounds in the distance.

While the ship's horn reminds us of the film's access to real locations in its offscreen space, the image at the same time closes us off from that fundamentally cinematic space. The shot of the set reveals the painful spatial limitations of the theatrical while adhering to them. Most of the offscreen space indicated in the rest of the film by sound effects (fog horns, the sound of rain) works to close the characters in—a narrative excuse to keep them within these spatial

limits. Offscreen sound merely recreates its role as offstage sound in scenes such as these.

Both the sound, the backward movement of the camera, and the last line of dialogue (as well as the way it is spoken) distinctively mark this as a closing point, and it is in fact the end of act 1. Such open acknowledgment of a film's theatrical genesis was sure to draw the ire of those who felt the resurrection of the theatrical was detrimental to the preservation of the cinematic. And the use of sound here (the dialogue, delivery, and symbolic sound—the Ordoona is leaving and the characters have no choice but to remain there together) is directly traceable to theatrical use of sound and directions for sound effects in the text of the play. Burch argues that

these theatrical beginnings are, in fact, the instrumentality of the camera stripped bare . Its essential transformational powers (its production of meaning) are thereby acknowledged , since even filming the theatre stage as such (i.e. filming the entire proscenium) destroys the representational effect, causes the image to appear as that of a stage .

(Burch 1979, p. 75; italics in original)

In other words, he sees no betrayal of the cinematic in this exposure of the theatrical, and certainly in this shot and a similar one at the end of act 2 the text comes very close to revealing the proscenium arch at the top of the frame.[4]

It should also be noted that although the exposure of the theatrical weakens the transparency of the narrative (its diegetic hold or "representational effect"), what might be called the "archaeological effect" grows stronger. We become aware of the age of the film, the archaicism of the acting, the play's "well-made" structure, the hesitant and confused conventions of films of this period. One feels a frisson of loss in the presence of a fragile replica of a moment locked in the past.

Following the first act, three additional scenes develop the visual and acoustic representation of Sadie. Scattered throughout the rest of the film are intriguing shots and parts of scenes that in their "oddness" contribute to the film's idiosyncratic feel: Macphail's oddly singsong delivery of his argument in favor of empiricism and tolerance; a "behind the cans" shot as Sadie reaches for some tamales; Horn rapturously quoting Nietzsche to Ameena; and a sight-gag close-up of a corkscrew, followed by a leering Horn, which is, one hopes, incomprehensible. The scenes I wish to examine in depth include a six-minute tracking shot of O'Hara and Sadie, Sadie's conversion, and the film's climax. It is in these scenes that the woman's voice is revealed as an issue , a problem to be contained by the narrative and by the transitional text.

The Veranda Scene

The six-minute tracking shot with Sadie and O'Hara offers an alternative to the camera moves, cuts, and dialogue of the opening scenes, and another pos-

sible answer to the question of how to make a sound film. While the shot is certainly a "significant instance of virtuosity," it also exemplifies what Bordwell et al. label "the excesses of early 1930s camera mobility."[5] Taking account also of the complaints of the actors, who criticized Milestone for making them do take after take of these difficultly staged scenes, it is not hard to see why this alternative did not become the norm.

However, the shot seems at first an undeniably egalitarian way of representing Sadie and O'Hara's relationship. The scene with O'Hara and Sadie on the porch employs a moving camera to define the couple and to illustrate their unity. For six minutes without a cut, the camera tracks and dollies and pans to maintain a two-shot of O'Hara and Sadie walking around the veranda of the inn, discussing her future. The dialogue is taken from the play and not significantly changed; it illustrates pursuit without pressure, an offering of common ground. The use of slang and O'Hara's reluctance to directly recommend a course of action as he tries to elicit Sadie's preference both work to gain her trust and consent.

Verbally, O'Hara repeatedly puts himself in Sadie's position, while never overtly telling her what to do. "Looka here! If something should go wrong—that is, about your getting to Apia—what'll you do?" He introduces a series of possibilities in case Davidson causes trouble, always carefully leaving the choice up to her. "Go back to the States, I suppose? . . . You don't want to go to Honolulu either, I suppose?" Eventually he suggests Australia and the set piece of their conversation (and of their courtship and alliance) is the story of Lefty (Biff in the play) and Maggie. This story serves several functions. It preordains the outcome of O'Hara's and Sadie's relationship by relating it through analogy with Lefty and Maggie as if it had already happened. It answers any questions before they can arise and contains the "problem" of her background (O'Hara's stressing of the equivalence of male promiscuity and female prostitution as mutually forgivable failings). It is also the speech whereby he reconciles Sadie to marriage and to men. She says afterward, "I thought I knew most all there was to know about men, until you came along" (Colton and Randolph 1936, p. 141).

O'Hara tells her that there's an "old shipmate of mine has his own place and wants a partner—These three years Lefty's been at me to get my discharge and come in with him. You'd like Lefty. We joined the service same time, sixteen years ago." Sadie says that if she were to meet Lefty and Maggie, Maggie wouldn't approve. He retorts,

I've an idea what's on your mind, Sadie. But Maggie's not the kind of female you're meaning. She's square from the toes up. Funny thing, how it is those that kick highest seem to settle down hardest. . . . You see, Lefty had been a kind of a hell-raiser. . . . I guess no woman who hadn't been on the rocks herself would have risked Lefty. It isn't likely a guy who didn't know the mill would have risked Maggie, either. Both knew the real thing when they saw it go. And they've never been sorry.

He makes it explicit that Maggie was a prostitute—"It never mattered to either of 'em that they met in Iweili." This cements the identification between Sadie and Maggie and creates the symmetry between the couples that ensures that Lefty and Maggie's "happily ever after" ending will be O'Hara's and Sadie's.

In the silent film Sadie Thompson , the equivalent scene is made up entirely of static shots and editing, mostly shot/reverse shot. Sadie and O'Hara sit on a settee in the middle of Horn's inn and chat. The rain, which is omnipresent on the sound track in the sound film's version, is not in any way a factor in the silent version of the scene. The dialogue, which again comes from the play, is drastically reduced.

Here, however, regardless of the dialogue, the camera has already linked Sadie and O'Hara in space and time. They never separate, going everywhere side by side and without a break. Sadie stops, worried about Davidson, and leans against a wall. The camera stops as O'Hara turns to face her. She gets up and begins pacing as the camera dollies back to keep them in a medium shot. For "romantic" dialogue (when O'Hara asks her if perhaps she's going to see someone special at her destination), the camera moves in and reframes them in a closer two-shot, but neither is ever separated for a single close-up. By waiting for the actors to begin or stop, even such extravagant camera movement seems internally motivated.

There are technological, formal, and economic, as well as ideological, reasons for presenting Sadie and O'Hara's courtship in a single long take. In a transitional text—or really in any film—it is necessary to address all of these before we can understand the implications for the speaking woman at their core.

Throughout transitional sound films we find a pressingly felt need to differentiate the new sound film product from silent films. In the many remakes of popular silent films, the underlying (and even overtly expressed) assumption was that the sound film would be "better" because of sound, that sound film could do things silent film could not, and that this would lead to a more effective emotional narrative experience. From a marketing standpoint, the movie Rain is able to give the audience more of the hit Broadway show Rain than Sadie Thompson , where the same scene preserves only a few lines of dialogue from the play. In the scene on the veranda, the film audience is able to hear directly almost all of the dialogue from the play, including great amounts of exposition and character background that had been lost in the silent film, and to hear the oppressive rain while seeing every second of the ebb and flow of conversation between Sadie and O'Hara.

Early critics of sound film (from Eisenstein to Arnheim) argued that synchronized sound, epitomized by synchronized dialogue, was redundant. Here, however, we see that even if the sound (the voice) is meticulously synchronized with the image, what the sound (the dialogue) conveys is unrepre-

sented and unrepresentable visually (short of elaborate flashbacks). The shot presents two people talking; the sound (dialogue and voice) elicits images of dance halls, "friends" male and female, Honolulu, Australia, the island's political structure, and images of women working. Psychological depth and a detailed "back story" for each character are values of drama and literature; they are only partially evoked through image and non-dialogue-bearing sound (the elements of silent film). Sound film increases access to this kind of character construction through use of a greater number of words. Words alone do not, however, account for the full impact of this shot (or any shot like it). The actors' delivery is crucial as well.[6]

Even if the long take had been popular with the public, however, economic considerations made it unlikely that it would be widely adopted. Filming such a long and complicated shot was prohibitively expensive and time-consuming. Lighting was difficult to work out and any mistakes in sound (flubbed line readings, a noise on the set) required doing everything over. Aesthetically, too, this form of realism can be very wearing. The undifferentiated sound effects, the constant drone of the rain, and the unedited take expose the fallacy that total continuity is automatically superior to the impression of continuity built by editing conventions. The "realism" achieved by such a shot is technological rather than narrative, and even then the long take is constantly threatening to undermine classical ideals of transparent cinematic expression.

There is only one major section in the veranda scene where the camera moves without an internal (character-instigated) cue. O'Hara and Sadie have stopped walking and sit on the railing of the porch. As O'Hara begins to tell Sadie about Lefty and Maggie, the camera, rather than stopping with them as it has until now, seems to be carried away by its own momentum. It moves off the porch and tracks around O'Hara and Sadie. As it does so, it passes a trellis with vines, which blocks our view of the characters during the crucial (verbal) juncture when O'Hara eliminates what would otherwise be seen as an obstacle to the formation of the couple (her past). The camera continues to move right in a semicircle and eventually returns up the porch steps to reframe them in a standard two-shot. When they stand and begin to walk, the camera dollies back with them as before.

Although this move "breaks up" a long speech by O'Hara, it more than flirts with exposing the enunciation. At the point when O'Hara and Sadie are becoming closest, a moment traditionally filmed in the least obtrusive way possible, the image takes us away from the couple and privileges itself instead. The image in effect denigrates the dialogue (and even the characters) by literally leaving it behind. Bordwell et al. point out that the "omnipresent point of view which cutting had provided during the silent era [and that can be seen in Sadie Thompson ] was replaced to some extent by a ubiquity yielded by camera movement" (Bordwell, Staiger, and Thompson 1985, p. 308). The absolute power of the transitional-period camera is shown by its flaunting such

a bravura move despite the needs of the narrative. With the continued volume of the "rain" sound effects and the loss of synchronization of lip movement and dialogue, the obstruction of our view of Sadie and O'Hara makes the crucial dialogue of this part of the scene hard to follow. Bordwell et al. go on to note that "both techniques"—camera movement and omnipresent montage-based point of view—fulfilled "fundamental functions," such as "narrative continuity, clear definition of space, covert narrational presence, [and] control of rhythm" (ibid.). As we see in this example, the narrational presence is anything but covert, while narrative continuity takes a back seat to technical continuity. The fetishization of the visual/audio continuity threatens to disrupt the seamless flow of the narrative, another reason why this kind of shot and this kind of camera movement did not become standard in classical sound film.

While the tracking shot on the veranda would seem to maintain a strict formal equality between the woman and the man, nevertheless it is O'Hara who urges action on a tormented, but passive, Sadie. And time and again it is Sadie/Crawford who leans into specially lit areas of the set so that the camera can isolate her still, suffering beauty. Even the long take finds a way to single out the woman as visual spectacle.

The woman's voice in this scene has no authority. Although synchronized in exactly the same manner as O'Hara's voice, Sadie's speech is contained by his context. O'Hara's terms are far more flexible than Davidson's, but even so, Sadie is trapped in someone else's discourse. With O'Hara, she is simply allowed more room to play his game. The fragmentation that denies her body cohesion in the introductory "Sadie" montage also makes it impossible for Sadie to be "O'Hara's girl." As a prostitute, Sadie belongs to everyone and no one, her body by definition available to many takers. In order for her to be the hero's prize, Sadie has to be put back together again. O'Hara makes her whole—and potentially his—by incorporating her into the fluid, continuous tracking shots that exemplify the marines throughout the text. Synchronous sound in a continuous take makes Sadie available, not equal.

At the very end of the shot, having received a letter from the governor insisting she return to San Francisco and not the idyllic Sydney, Sadie agrees to go and see the governor with O'Hara to appeal. As she and O'Hara exit the frame on the left, the camera executes a swish pan right. This swish pan differs from earlier ones by being slightly slower, so that we can see that there are no cuts hidden in it. Through the blurred image we can just make out the back of the wall of the veranda until the camera stops and O'Hara and Sadie run back into the shot from the right. They grab their coats hanging on the wall at the end of the porch and run out left through a door leading into the inn.

Again the importance of the continuous image overwhelms the narrative with its need to announce itself as image, continuity for continuity's sake. The purpose of this slowed swish pan is to maintain the integrity of the six-minute

shot, complete without a cut. Only here the shot is maintained regardless of the absence of the couple whose relationship the "wholeness" of the track has been designed to define. The exits and entrances of Sadie and O'Hara before and after the swish pan confuse us spatially. In drawing attention to itself, the shot tempts the audience to reconstruct its production—evidently the actors ran behind the camera as it panned right and reentered the last "shot." Offhand it would seem difficult to problematize space when the continuity of space is so meticulously insisted upon, but this shot does manage it. A last reason mitigating against the popularity of the long take is that a particularly long take or sequence shot is hard to get out of without it calling attention to itself.

The end of this scene firmly establishes that sound in no way legitimizes or validates the woman's speech in the absence of visual and narrative support. In the silent film, Sadie's outrage at Davidson after receiving the governor's letter bursts forth in a tirade when she accidentally meets him as she and O'Hara are setting out to see the governor, a scene that takes minutes and is made up of twenty-seven separate shots (not counting titles). In the sound version, the scene takes three shots: Sadie enters the inn and begins to yell at Davidson in a long shot, there is a brief reaction shot of Davidson looking at her, and then we return to the original shot of her yelling until O'Hara drags her out. In effect, it is one long take with a cut-away in the middle.

In the silent version, the editing makes Sadie dynamic—a star—fully constituted by the text in all its systems: composition (she is the drama and movement of the scene as she fills the frame with violent gestures), editing (cuts to "keep up" with her as she pursues Davidson from room to room), and titles (presenting highlights of what she says and Davidson's brief, inadequate interjections). Sadie dominates the scene as Davidson stands pinned against the wall, hiding behind furniture.

In the sound version, while Sadie is having the last word, Davidson stands

on the stairs high above her, secure in his spatial superiority. Her vocalized tirade becomes less powerful because we see the string of words falling on deaf ears. When O'Hara drags her out the door, undermining her anger, as in every version, it relieves Sadie from occupying a position whose weakness only she does not recognize. Davidson never moves. As with the first close-up of Ameena, sound only allows Sadie to speak her own ineffectualness.

"Radiant, Beautiful"—The Voice that Exceeds Language

Just as visual spectacle competes with narrative, what we might call audio-spectacle constantly invites the auditor to bathe in a wash of sound, music, and voice, all promising pleasure in themselves without need of narrative, psychologically motivated characters, causality in space and time, or closure. As in the theories of visual spectacle of Lea Jacobs et al.,[7] duration, or lingering on a shot, detaches it from the linear progression of the narrative and invites a similarly nonlinear, analogical indulgence on the part of the viewer. Audio-spectacle also guides us away from "content" (language, character psychology, exposition) and toward the quality of the sound, irrespective of whether music, voices, or effects are on the sound track.

Sound's ability to envelop the spectator and abolish the space separating the hearer and the source of the sound has been widely commented upon. Barthes describes the elusive, but overwhelming, pleasure that comes from listening to the voice: "It possesses a special hallucinatory power, [uniting] in one plenitude both meaning and sex" (Barthes 1974, pp. 109–10). Hanns Eisler describes the way music fills the gap between audience and screen—and, arguably, between scenes and between shots in silent films. Mary Ann Doane details how the projection of sound from behind the screen reenforces the bond between spectator and image, minimalizing the threat of sound disrupting viewer/listener identification with the image, and Lucy Fischer adds an analysis of the essentially spatial function of sound effects and early sound film's use of them to add depth, scale, and presence to the image.[8]Rain acknowledges this impression of the transcendence of sound, particularly with regard to the voice—a voice separable from dialogue. The last third of the film presents a series of ways of narrativizing that excess so as to represent vocal transcendence.

When Sadie speaks to Davidson the night before she is to return to San Francisco and a prison sentence, he is pacing on the veranda. Sadie leans out of a window to say goodnight. In another interesting use of the swish pan, a close-up profile shot of Joan Crawford facing screen right is followed by a swish pan to the right. Instead of seeing what she sees, the pan ends inexplicably on a full-face close-up of Crawford. The effect of the shot, which is spa-

"Radiant. Beautiful."

tially impossible, is as if Sadie has been removed from any real spatial context and instead floats as pure, ethereal spectacle. As she gazes into the great beyond, Sadie quietly restates "her" reasons for going back, couched in Davidson's language of Christian suffering and sacrifice. In this way, the text narrativizes the relationship between the voice and the imaginary. It is Sadie's voice infusing Davidson's words that provokes Davidson's desire. Both her voice and her image—her face on display as an icon of the "star" and of the character's spirituality—are offered as transcendent, promising fulfillment of desire through an appeal to Davidson's imaginary, which is built on religious discourse. To him she has become "radiant, beautiful."

At the same time, Sadie's image and voice are presented to us, the film's spectators. The synchronization of voice and image does not fully recuperate the excess of the voice. As Sadie recites the religious rhetoric on punishment and redemption, her voice filling the dark frame and warming her blank facial expression, the spectator is engulfed in an imaginary unity with the star/image/other. Rather than occupying a spatial position, the lack of ambient sound denies the particularity of the voice in space, allowing it to fill the theater, becoming something inside the hearer rather than "out there." The voice does not so much exceed the symbolic as fulfill it by imbuing it with physical pleasure, the imaginary, and the maternal that complete patriarchal authority with this offering of wholeness to the subject.

The sound of the voice occupies a specific relationship to desire when it is reproduced in film. Every voice one hears reproduced is poised on the edge of poignance, an indicant of loss, a promise of fulfillment that foretells the imminence of its departure. In discussing the relationship between the spectator and the image of an actor, Metz points out that the absence of the physical body of the actor makes one yearn ever more strongly for the star, knowing

he or she is already gone and all that is left is a disappearing trace (1982, pp. 62–63). Sitting on the edge of one's seat, listening, the spectator/listener "glimpses" the uncapturable, a voice receding in the emptiness—an emptiness vividly signified in early sound films by the ever-present static and the striking lack of music. Desire is reopened, fulfillment dissolving the moment it is caught. Unlike photography, which freezes time, cinema and phonography replay time in its transience. The voice slipping away is recapturable through repetition, but it is nevertheless always retreating.

In considering sound in film, the voice must be theorized separately from dialogue. The voice is more than dialogue (see Marie 1980). Dialogue existed in silent film as pure language, represented in graphics and linked tenuously to the image through an abstract, logical process of connection through contiguity. But it is the voice in sound film that makes dialogue matter , that takes it out of its narrative function and makes it sound, that invokes a psychological, imaginary system of spectacle as opposed to the purely representational association of title and image in silent film.

Dudley Andrew once defined art as "the radical middle between the uncoded and the coded."[9] Although I would demur at the term art because it is itself so fully coded in terms of high culture, I agree that what I'm talking about in cinema is precisely the play between the uncoded—the ineffable that beckons the imaginary and is insistently repressed—and that which functions entirely within the symbolic. While dialogue is language, is the symbolic, other categories of sound, including voice, can slip out of language and narrative and assume the appearance of the uncoded, ravishing us with seemingly direct sensory experience. While it is asserted that there is nothing that is uncoded, no sensory experience that is experienced directly, I think it can be agreed that portions of the image and the sound track exceed the major code that seeks to contain them, namely, narrative.

Sadie's Conversion

The scene of Sadie's conversion tries to locate the space between voice and dialogue without letting voice escape its function in service to the narrative. In the silent version, Sadie's conversion is a matter of vision. Sadie argues with Davidson and returns to her room, where she paces./Shot of an open window with rain pouring down./Sadie, pacing./The window slams shut and breaks./Sadie jumps, scared./Sadie, hiding in a corner, stares into space./Dissolve to Sadie walking into a jail cell./She turns as the bars of the cell close in front of her./Back in her room, Sadie screams for Mr. Davidson./Upstairs, Davidson and his wife pray./Sadie screams at the ceiling./Davidson looks at his wife and goes to the door./Sadie screams again./Davidson walks down the stairs to her room./She opens the door./In her room he sits, puts her

hands together, and tells her to pray. Crosscutting and Sadie's "vision" of herself in prison fuel the scene, which has few titles and establishes its major points through images, pantomime, and editing.

In the sound film, the conversion is not simply a matter of substituting sound or hearing for vision. Instead, a new hierarchy is instituted, one with a complex interaction of camera movement, editing, mise-en-scène (from silent cinema), dialogue, voice (from theater), and voice-recording and sound ef-

fects and their relation in the sound mix from sound technology. The excess of the voice (in this scene Davidson's) is accounted for by relating its power to the process of hypnosis. Twice O'Hara comments that the converted Sadie acts "like she's doped," "like she's hypnotized." The sound film depicts this hypnosis by focusing on the power of Davidson's/Huston's oratorical delivery.

In hypnosis, the voice, as much as the words of the hypnotist, is absorbed by the subject as his/her own inner voice and thoughts (see Chapter 1). The conversion scene dramatizes this as Davidson's voice fills the close-up of Sadie, his words becoming hers as if his prayer was her own spontaneous thought.

As Sadie stands at the bottom of the stairs and, looking up at Davidson, begins to tell him off, he begins to pray. Sadie, photographed from a high angle, begins to ascend the stairs toward Davidson, dramatically protesting, "You tell me to go back and suffer. How do you know what I've suffered? You don't know, you don't care, you don't even ask and you call yourself a Christian!" As she moves, the camera pans left to keep her centered and moves

in. Davidson, from a low angle, prays out loud, "Our Father, who art in heaven. . . ." Sadie reaches the upper part of the stairs as Davidson's dialogue continues in a sound overlap. Sadie: "Your God and me could never be shipmates, and you can tell Him this for me—Sadie Thompson is on her way to Hell!" Having reached the famous finish of the second act (and at the same time used words all the more potent for being forbidden by the Production Code), Sadie waits for a reaction from Davidson. He continues, uninterrupted, praying on in a droning, monotonous voice: "Forgive our poor lost sister, Our Father who art. . . ." Sadie retreats uncertainly. At the bottom of the stairs, Sadie falls to her knees and slowly begins to repeat occasional words from the prayer. When Davidson, heard in voice-over, finishes the prayer, Sadie is reciting every word. In a close-up, Davidson realizes she is with him and, smiling, raises his voice as they repeat the prayer a third time. The camera moves to a long, high-angle shot of the entire set, then cranes up past the ceiling, panning out into the darkness, where the sound of rain drowns out their voices.

The use of the Lord's Prayer is especially effective because the audience knows it, the culture presumes it to be known, and therefore Davidson speaks not just a vague "religiousness" (in keeping with the Production Code's refusal to let Maugham's "Reverend" Davidson be an actual missionary in the film versions), but a concrete formal expression of religion that exists as a whole and does not need to rest on internal persuasiveness. Because the words of the prayer are so well known, it is not necessary for the audience to listen to what Davidson says as much as to how he says it. The predictability of the words guides our attention away from the verbal discourse and toward the rhythmic, hypnotic quality of the reading and Huston's attractive baritone. As Sadie backs unsteadily down the stairs, Davidson's voice imposes on the image of her face, filling all the spaces in the same way the sound of the rain has in other scenes.