The Main Exhibition Hall

At the entrance to the main exhibition hall, three panels on the right display photographs of the sites of Kleonai, Argos, and (from the air in 1984) the Sanctuary of Zeus with the Stadium at the lower right.

KLEONAI was a city-state of secondary size and significance located in the valley east of the Nemea valley (see p. 10). It has never been excavated, although the remains of a small Temple of Herakles of Hellenistic date are visible and evidence of other monuments, such as a theater, is discernible on the surface. Nemea, never a city-state but rather a Panhellenic athletic and religious festival center, was originally controlled and administered to by Kleonai (see nn. 35 and 38). According to ancient literary tradition,[17] the Nemean Games were founded in 573 B.C. and were controlled by Kleonai as of that date.

ARGOS , a major power in the ancient Greek world, is located about 23 km. south of Nemea by the modern road. In the 5th century B.C. it expanded, swallowing other, smaller, city-states such as Tiryns and Mycenae. By around 400 B.C. Argos had gained control of the Nemean Games and of the site itself (and, perhaps, of Kleonai as well), and thereafter the games were more frequently held at Argos than at Nemea. Visitors to the museum can follow the history of the shifts between Argos and Nemea through the medium of the archaeological artifacts on display. Although the location of the stadium for the games at Argos has not been excavated, the contours of a stadium are recognizable in the ravine between the Larissa and Aspis hills.

[17] Hieronymous, Chronicle (ed. Fotheringham 1922) 179.

Fig. 5.

Aerial view of the Temple of Zeus, 1977.

The topography in the AERIAL VIEW of the Sanctuary of Zeus and the Stadium in 1984 (Fig. 6) differs from the present (1988) topography in that the dirt road that once ran east-west through the sanctuary north of the museum was replaced by a bypass to the east in 1985.

To the left of the entrance, on the opposite wall, is a MAP of the eastern Mediterranean. The Panhellenic games at Nemea (like those at Olympia, Delphi, and Isthmia) attracted both competitors and visitors from this whole region. The map shows where they came from, according to ancient written sources or the evidence of coins found in the excavations. Surely other cities, however, provided visitors for whom we have no specific evidence.

Three cases in front of the map hold a sampling of the COINS , a few of which have been reproduced in photographs on the wall to the left. The display gives an idea of the range of geography and chronology represented by the coins. The heavy proportion of silver to bronze may be explained by the long-distance traveler's need for the more valuable silver coins, which were then left behind at Nemea, either out of carelessness or in the form of dedications.

Case 1:

Coins from the Neighborhood

This display includes representative coins from the city-states near Nemea. It is not surprising that three of them—Corinth, Sikyon, and Argos—provided a large percentage of the more than four thousand coins found at Nemea. Nemea's closest neighbors, Kleonai and Phlious, are less well represented, at least in part because of limited issue and circulation. Then, too, Kleonai was incorporated into Argos for much of its history. (Samples of all the coin types in this case are shown in photographs on the wall.)

Case 2:

Coins from Distant Visitors

Here are displayed representative coins from many Greek city-states. These include the heavy silver "turtles" of Aigina, issues of individual cities in Arkadia as well as of the Arkadian League, and the "owls" of Athens. Other city-states and regions represented are Eleusis, Megara, Boiotia, Thebes, Tanagra, Phokis, Opuntian Lokris, Chalkis, Histiaia, Lamia, Oita, Elis, Hermione, Epidauros, Messene, Tiryns, the Achaian League, and Sparta.

Case 3:

Coins of Hellenistic and Later Times

This case contains three distinct collections. The first shows representative coins of Macedonian kings beginning with

Fig. 6.

Aerial view of the Sanctuary of Zeus and the Stadium, 1984.

Philip II and his son Alexander the Great. The games, long absent from Nemea (see pp. 43 and 61-62), were returned around 330 B.C. , that is, just after the Macedonian victory at Chaironeia in 338 B.C. Scholars generally agree that after his victory there, Philip instituted a "Greek League of Nations."[18] The synedrion , "council," of this league was to meet each year at the Panhellenic festival center that was celebrating the games (Olympia, Delphi, Isthmia, or Nemea). It seems likely that the return of the games to Nemea at this time was occasioned by the creation of the league and that the concentration of Macedonian coins found in the excavations reflects the influence exerted by those kings upon the site.

The second collection in case 3 is of Roman times and Roman emperors. Because the games moved permanently from

[18] Scholars today call this league the League of Corinth, even though there is no ancient evidence for such a name.

Nemea to Argos well before 100 B.C. , Nemea received only casual visitors after this date. Thus few coins from Roman times have been found in the excavations; nearly all of them are on display here.

The third collection shows samples of Byzantine and Frankish coins from about A.D. 500 to 1300. Much evidence remains of a 6th-century Early Christian community which grew up among the ruins (see the account of case 10, p. 43). Not surprisingly, the Dark Ages which followed are poorly represented at Nemea, but there is great numismatic activity from the time of Emperor Manuel I (A.D. 1143-1180) through the Frankish invasions of the 13th century, including even English coins issued by Henry III from 1222 to 1237. The excavations have revealed, however, very few other signs of activity during that time, and it is uncertain whether these coins reflect a permanent community or some other activity.

Case 4:

The Myths of Nemea

All ancient sites had their own myths, and the Panhellenic centers were no exception. The myths for Nemea are represented in the excavated material in case 4 on the west wall of the main exhibition hall. In Greek mythology, perhaps no hero is so enduring as Herakles, and his victory over the lion—the first of his twelve labors—clearly associates him with Nemea.[19] Because the skin of the lion was impenetrable, Herakles had to wrestle the lion and strangle him. Then, with the lions own claws, Herakles skinned the beast, thereafter wearing the skin over his back as a kind of armor (Alexander

[19] This myth was very popular and occurs frequently in art and literature. The earliest literary example is in Hesiod, Theogony , 327-32 (8th century B.C. ). It is interesting that Hesiod himself, warned by the Pythian oracle that death would overtake him in the fair grove of Nemean Zeus, avoided Nemea (cf. Thucydides 3.96.1 and Plutarch, Moralia 162D). Unfortunately for Hesiod, there was also a grove of Nemean Zeus at Lokris.

the Great adopted this same iconographical device in his coins; see case 3, C 337). One reads in general handbooks and guides that Herakles, as a thanksgiving to his father Zeus for his victory over the lion, established the Sanctuary of Zeus and the games. The only archaeological evidence of the myth discovered at Nemea consists of small bronze lions head attachments and a gold foil relief representation of Herakles' face with the lions skin tied under his chin (BR 1040 and GJ 26; see the photographic enlargements on the wall behind case 4). The paucity of evidence is not surprising, however, for the connection between Herakles' victory over the lion and the founding of the Nemean Games was not mentioned in ancient literature until the 1st century after Christ.[20]

The proper foundation myth for the Nemean Games has to do with a set of characters less well known but established well before the 5th century B.C. , when Aeschylus wrote a play about them, only the title of which survives. Of a later play by Euripides, Hypsipyle , perhaps a third has been preserved on a papyrus from Egypt, and that together with later texts gives us the following story.[21]

Once upon a time in Nemea there was either a priest of Zeus or a king named Lykourgos who, with his wife Eurydike, longed for an heir. After many years of frustration, a baby boy was born, and the happy couple gave him the name Opheltes. Lykourgos sent to Delphi to ask how he might ensure the health and happiness of his baby, arid the Pythian

[20] See Virgil, Georgics 3. 19 with scholium (Servius-Probus) ad loc . Attempts to use the texts of Callimachus, Victoria Berenices (text in ZPE 14 [1977] 1-50), and Euphorion apud Plutarch, Moralia 677A (= Powell, Collectanea Alexandrina 84), to establish a cause-and-effect relation between the lions death and the founding of the games are less than convincing. But even if such interpretations could be proved correct, the relation would still not be traced earlier than the 3rd century B.C.

[21] For the sources and discussion of the myth, see E. Simon, "Archemoros," AA (1979) 31-45; and W. Pülhorn, "Archemoros," LIMC II (Zurich 1984) 472-75. Note that it was known already to Simonides of Keos, to Pindar, and to Bacchylides.

oracle responded that the baby was not to be allowed to touch the ground until he had learned to walk.

Upon his return to Nemea, Lykourgos acquired a slave woman named Hypsipyle,[22] to whom he entrusted the care of the baby Opheltes, with the stipulation that he was not to be allowed to touch the ground. One day Hypsipyle was carrying the baby in the valley when she was approached by the Seven Champions, who were on their way from Argos to Thebes. They asked Hypsipyle for something to drink, and she led them to a spring or stream where she laid the baby down on a bed of wild celery (

Given this mythical background for the Nemean Games, it would not be surprising to find relevant physical evidence. Indeed, a small bronze figurine in case 4 (Fig. 7) must represent Opheltes; the pose of the figurine is similar to that of Opheltes on the Corinthian sarcophagus. Although the figurine belongs to the Hellenistic period, it was found south of

[22] This Hypsipyle has a history of her own. The daughter of King Thoas of Lemnos, she ruled the island and received the Argonauts on their (not always very energetic) quest for the Golden Fleece. She had two sons, Euneos and Thoas, by Jason, but after Jason's departure she was captured by pirates and sold to Lykourgos of Nemea. In the Euripidean version of the story she is rescued from Nemea by her two sons after a miraculous recognition; see Euripides, Hypsipyle (ed. Bond) 16-18 and 147-49.

[23] F. P. Johnson, Corinth IX, Sculpture, 1896-1923 (Cambridge, Mass. 1931) 114-19, no. 241. For more recent photographs, see Simon, op. cit . (n. 21) 40-41, Figs. 7-9.

Fig. 7.

Bronze baby Opheltes (BR 671).

the Temple of Zeus in earth disturbed in the 6th century after Christ. Its archaeological significance is therefore limited.

Much clearer is the evidence of the hero shrine, or Heroön, discovered southwest of the Temple and west of the Bath (no. 19 in the model; see pp. 34, 104-10). An aerial photograph (see Fig. 36) of this Heroön near case 4 shows it as a lopsided pentagon built of rectangular blocks overlying a curvilinear predecessor built of field stones (this structure is dearest at the lower left, or southwestern, corner of the photograph). The religious character of the Heroön was established by, among other evidence, the deliberate burial of a krater (P 539 in case 4) with a stone lid at the northeastern corner of the enclosure, next to the foundations. A photograph on the wall shows this krater at the moment of discovery. Its contents

may have included the beans which were set in such foundation trenches when a structure was dedicated to the gods.[24]

Within the enclosure were deposits of ash, carbon, and burnt bone from sacrifices and large quantities of other artifacts; another wall photograph shows some of this material during excavation. Everything in case 4, with the exception of the lion's head (BR 1040), the gold foil Herakles (GJ 26), and the figurine of Opheltes (BR 671), came from this enclosure. The miniature vessels are characteristic of the votives one might expect in a shrine, and the drinking cups (e.g., P 510) were used for libations poured out during sacrificial rites. The fragment of a terracotta column (AT 83) once supported a basin for holy water (perirrhanterion ), the rim of which may well have been inscribed with a sadly fragmentary dedication (P 547, a-f). The cup-skyphos (P 546), which bears an inscribed dedication by a victor as well as a magical inscription, also shows the decidedly religious character of this enclosure. The silver coins of Sikyon (C 1639) and Aigina (C 1645 and 1649) would also have been appropriate dedications in a shrine.

Even more suggestive, however, is the iron caduceus (IL 324), the symbol of Hermes Psychopompos, leader of souls to the underworld. It hints that the shrine is chthonic and heroic. The same conclusion derives from the lead curse tablets, two of which are displayed in case 4 (IL 327 and 367). Such curses are appropriately deposited in the shrine of a hero. The examples in case 4 bear erotic curses in which an anonymous author hopes to alienate the affections of a woman from another man. Thus IL 327 reads: "I am turning Euboula away from Aineas, away from his face, from his eyes, from his mouth, from his breast, from his soul, from his stomach, from his penis, from his anus, from his whole body am I turning Euboula away from Aineas."

[24] See Aristophanes, Plutus 1198 and Pax 923, and scholia ad loc . I thank C. Simon for this reference. See further p. 107, on the Heroön.

Fig. 8.

Terracotta baby Opheltes (TC 117).

To which hero was the shrine at Nemea dedicated? Pausanias, who visited Nemea in the mid-2nd century after Christ, found there a tomb of Opheltes within a peribolos which also contained altars. He defined the peribolos as an enclosure of stone (

To the fight of case 4, in the northwestern corner of the room, is the right half of a MARBLE RELIEF (SS 8), part of a dedicatory relief which had been reused in a house of the later 4th century B.C. (see p. 76 and Fig. 23). It portrays a male figure standing in front of a seated female. The figures have yet to be identified, and the date is in debate, although it is probably in the 460s B.C. Clearly the piece must stand early in the Classical period since it combines elements of the Classical, especially in the male figure, with elements of the earlier, Archaic, period, especially in the female figure. The male's clothing, for example, is plastic, the female's stiff and two-dimensional. The handling of depth is awkward both with regard to the female's feet and in the relation of her breast to her shoulder.

Cases 5 and 6:

Religious Dedications

The artifacts from various votive deposits displayed here reveal many characteristics of worship in the Sanctuary of Zeus. On the top shelf, left, of case 5 are artifacts from a votive deposit consisting of an informal pit with ashes from a sacrifice (see the photograph on the wall beside the case). In this pit were some small terracotta toys or animals (M I and TC I ) and several dozen miniature vases (P 2-44). It would appear that credit went more to the quantity than the size of the vessels dedicated. The only larger piece of pottery gives us the name of the dedicator, Aischylion, which is scratched on the bottom of a skyphos (P I ).

The top shelf, right, displays material from a ritual meal pyre. The vessels, of normal size, include utilitarian items such as lamps (L 187 and 189). The meal appears to have ended with the smashing of the drinking cups, perhaps by means of the rocks discovered in them. On the wall one can see the skyphos (P 1338) still in the ashes of the pyre with the stone (ST 651) inside it.

The bottom shelf of case S represents yet another type of votive deposit. On the slopes of the valley's eastern side, several hundred meters from the Temple of Zeus, a simple pit was discovered cut into the soft natural bedrock. Roughly circular, about 2 m. in diameter and 1 m. deep, this pit contained some 526 vases. Many were nestled inside one another and neatly stacked, and the pit cannot, therefore, represent a garbage dump. Different shapes were represented in rich abundance: the kylix (P 1022), skyphos (P 951), lamp (L 164), miniature hydria (P 1057), and kalathos (P 1004). Although the dates of the vessels range over at least two generations, all were buried together about 480 B.C. They may reflect an attempt to hide votive offerings of the Sanctuary of Zeus or some other shrine, for there is no clear evidence of the deity to whom they had been dedicated.

Case 6 contains other types of dedications made in the Sanctuary of Zeus. The silver coins on the circular stand were found in a deposit of ash and burnt bone from sacrificial debris. Although the circumstances of their discovery indicate that they were consecrated to Zeus, it is not clear whether they were deposited by a single person, for their geographical range is fairly large: Sikyon (C 901, 902, 904), Athens (C 903), Aigina (C 905), Phlious (C 906), and Corinth (C 1659). To the left of the coins is material from the destruction debris of the Early Temple of Zeus (see case 19, p. 60). Each fragment must represent part of the wealth of the sanctuary in the early 5th century B.C. This wealth includes a miniature double ax (IL 376), the head of a young man (BR 897), attachments from vessels or furniture in the form of lions' heads (BR 849, 896, 898), a votive plaque with the incised figure of a bull (BR 708), and (toward the center of the case) a lead kouros, or young man (Fig. 9), made from a mold. Another kouros, from Isthmia, was made from the same mold—an indication of direct commerce between the Panhellenic sanctuaries.

Fig. 9.

Lead kouros (IL. 201).

Little has survived of the statues of victorious athletes—another type of dedication common at Nemea. The olive leaves which once made up the crowns on such statues (BR 74, 109, 139, etc.) and scraps of bronze statuary which can be recognized as hair (BR 999), feathers (BR 1000), or an eyelid (BR 990) bear mute witness to the devastation the site has endured. Smaller dedications were less attractive to vandals and thus remain to the archaeologist. These include terracotta figurines of horses and riders (TC 38, 90, 131, 136, etc.), of a Persian warrior (TC 91), of the god Pan (TC 95), and of Zeus himself (TC 69). So too miniature vases like those already seen in other contexts abound (P , 54 and 55, 333 and 334, etc.), as do aryballoi , the flasks in which ancient athletes carried the oil with which they coated their bodies before exercise (P , 97, 239, 559). In addition to such artifacts known to have belonged to Zeus because they were discovered in sacrificial contexts, other, more prosaic, items are specifically labeled as his property. One example is the mug incised

On the wall between case 5 and the picture window is a PHOTOGRAPH of the open square which surrounded the Temple of Zeus. Excavations here revealed the pits which once contained the cypress trees of the Sacred Grove (alsos in Greek; see pp. 157-59 and Fig. 58). The cypress, sometimes associated with mourning, would have been especially appropriate to a sanctuary associated with the death of the baby Opheltes.

A STONE PILLAR next to these photographs has thirteen vertical facets above a rough "base" which was originally inserted into the ground (I 107). Near the top of the pillar is the inscription W POS EP IP OL AS , "Boundary of the Flat Area," in Argive letters of the late 4th century B.C. It would seem, then, that the Sacred Square at Nemea was officially called the Epipola just as Olympia had its Altis and Delphi its Peribolos.

Model

In front of the picture window is a model, on a scale of 1:200, of the Sanctuary of Zeus as it would have appeared in about 300 B.C. It is the work of Robert Garbish (compare the plan of the sanctuary, Fig. 10). The flat open squares represent areas not yet excavated. Buildings numbered 1-8 represent the first 8 oikoi (see p. 118 for the various meanings of this word) erected by various city-states for the use of their citizens and guests at Nemea (see pp. 62-63, 67-71, 117-27, 160-68). Numbers 9 and 10 are the Temple and Altar of Zeus, respectively, whereas 11 and 13 represent buildings the precise nature of which has not been established. Number 12 refers to the Epipola with its Sacred Grove of cypress trees and other altars and monuments. The Dining Establishment (14) is attached to some of the oikoi but also clearly differs from them. The number 15 marks an area of light industry (see case 20, p. 63) and a series of wells (see case 9, p. 39). The hotel, or Xenon, is 16 and the Bath 17. The Nemea River is marked 18, and to the west of it

Fig. 10.

Plan of the Sanctuary of Zeus with the walk indicated.

is the hero shrine, or Heroön (19). The region labeled 20 contains a number of houses, probably for the priests or the judges of the Nemean Games.

In the view from the window, the houses (20) are in the immediate foreground, just beyond the edge of the grass. The highest and most massive remains beyond them, consisting largely of gray stones, are of the Early Christian Basilica which lies over the Xenon (16). To the right, or east, of the Basilica the wall of the Xenon comes out from under the church and continues eastward. Finally, the columns of the Temple of Zeus (9) are clearly visible in the background.

Near the model of the sanctuary is a MODEL OF THE STADIUM . Its orientation to and distance from the sanctuary are

proportionally correct, although it is in fact higher in elevation. Indeed, the side of the Evangelistria Hill into which the Stadium was built is visible from the sanctuary model through the window above and behind the Stadium model.

On the wall to the right of the picture window are two groups of color representations of the various events in the ancient games. These have already been described (pp. 4-5).

Below them is a STARTING BLOCK with a single groove for the toes of the runner (A 100). It was probably used originally in the early stadium of the 6th century B.C. , which has not yet been discovered, although it must have been near the Temple of Zeus.[25] As can be seen in the photograph on the wall above, the block was reused as a threshold in a door of the Xenon (cf. p. 169). Beside this starting block is a BLOCK OF HARD GRAY LIMESTONE on the upper surface of which is carved a small groove for a single foot (A 215). Like similarly grooved blocks found in Corinth, this one is from a starting line. A vertical socket at one end of it received a post marking the division of lanes; a lambda (L ) inscribed in front of the socket marks this as the twelfth lane. This block cannot be from the Stadium and so might be from some other race course, perhaps that of the gymnasion . Two more of these blocks are in the foundations of an Early Christian basilica on the crest of Evangelistria Hill.

On the north wall above and to the right is an AERIAL PHOTOGRAPH of the Stadium as it appeared in 1980 (see Fig. 61), with the main features—starting line, water channel, judges' stand, and tunnel entrance—marked out.

On the CENTER ISLAND opposite the aerial photograph of the Stadium is a pair of the terracotta water pipes which brought fresh drinking water into the Stadium (TC 40 and 41). The joints of these pipes, which date from the late 4th century B.C. , were originally sealed with a white clay mortar, in-

[25] See D. G. Romano, "The Early Stadium at Nemea," Hesperia 46 (1977) 27-31.

dicating that water may have come into the Stadium under pressure. Two photographs on the panel above the pipes show them in the Stadium during their excavation.

The other (southern) side of the center island exhibits two terracotta water channels (TC 107 and 83) and an amphora (P 320) which was reused in the entrance passageway to the Stadium as a settling basin, as can be seen in the photograph on the panel above. Water ran into the amphora through "windows" cut in its sides, allowing dirt and debris to settle out before the water continued its journey. This channel is discussed further on page 175. Also on the panel above are detailed photographs of two artifacts in case 7: a bronze strigil (BR 857), with which an athlete scraped off the sweat, oil, and dirt at the end of his exercise, and a dedicatory plaque (BR 1098).

Further on along the NORTH WALL of the exhibition hall is a fragment of stone from a voussoir of the Stadium tunnel and, in the photograph above, the same stone at the time of discovery, fallen on the floor of the tunnel (I 70). This stone, like so many still in place in the tunnel, bears a scratched graffito. Now incomplete, it originally gave the name of an athlete with the adjective kalos , "beautiful."

A photograph on the wall to the right of I 70 shows the tunnel during excavation. Although the two ends had silted shut, a considerable open space in the center was used as a refuge in the 6th century after Christ (cf. pp. 47, 188-90).

The next photographs show other graffiti in the tunnel. One, I 59, has the verb NIKW , "I win," followed, in a different hand, by the name Telestas. This is probably the Telestas who won the boxing event at Olympia in the boys' category in around 340 B.C.[26]

[26] Pausanias 6.14.4. The date of Telestas's victory is not absolutely precise and depends on the career of Silanion, the sculptor of Telestas's statue at Olympia, cf. L. Moretti, Olympionikai. I vincitori negli antichi agoni Olimpici (Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Memorie , ser. 8, vol. 8, Rome 1957) no. 453.

Fig. 11.

Aristis stele (I 4).

The other graffito, I 63 (see Fig. 66), has AKPOTATOS KAL OS , "Akrotatos is beautiful," followed, in a different hand, by TOY G PAY ANTOS , "to the one who wrote it." Akrotatos is almost certainly the Spartan prince who was king from about 265 to 252 B.C. , well known for his physical beauty and his penchant for "Persian luxuries."[27]

At the base of the wall below the photographs just mentioned are TWO BLACK MARBLE STATUE BASES from the Stadium. ST 126 preserves the outline of a left foot, which would have been leaded in place. ST 260 preserves the lead which held its statue in place: the statue had two projections from the sole of each foot rather than the outline of the foot itself. Given the location of these bases near the starting line of the

[27] Plutarch, Agis 3.4 and Pyrrhus 26.8, 28.2-3; Pausanias 3.6.6; Phylarchus apud Athenaeus 4.142b. The precise grammatical significance of this graffito has generated considerable interest; see Bibliography, p. 202.

Stadium, they may well have held statues of victorious athletes and should be dated to around 300 B.C. .

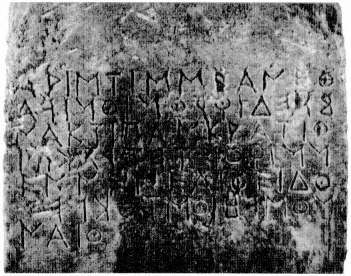

Between the two black marble bases stands a relatively tall LIMESTONE PILLAR (I 4), the top of which has two square cuttings, each with smaller sockets within (the right one still has some lead in place). These would have held a statue, but one of a much earlier date than those mentioned in the preceding paragraph. On the face of the pillar (Fig. 11) is a very early Greek inscription with curious letter forms whose lines read alternately from left to right and right to left. (This style of writing, from a time when the Greek language had not yet settled into a standard written form, is called boustrophedon , from the turning of the oxen at the end of each plowed furrow in a field.) The stone speaks: "Aristis dedicated me to Zeus, the son of Kronos, the king having won the pankration four times at Nemea. (Aristis) the son of Pheidon of Kleonai." The forms of the letters indicate that it was around 550 B.C. that this local boy did very well in the Nemean Games over a period of at least six years.[28]

Case 7:

Athletic Equipment

This case is devoted to athletic gear. In the left (northern) end is material found east of the Temple of Zeus in a single pit, as can be seen in a photograph on the north wall. It includes an iron discus (IL 419) weighing about 8.5 kg., as opposed to a typical weight of 2-3 kg. for the more usual stone or bronze discuses; a jumping weight, or halter , of lead (IL 418); javelin points (IL 420 and 435); iron spits, called obeloi (IL 421 and 424); drinking cups, or skyphoi (P 867-870); and a miniature oinochoe (P 866). This deposit would seem to represent a party following the (successful?) conclusion of a competition

[28] D. W. Bradeen, "Inscriptions from Nemea," Hesperia 35 (1966) 320-23; cf. L. H. Jeffery, The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece (Oxford 1961) 148 and 150, no. 5.

in the pentathlon, after which both athletic and drinking gear were dedicated to Zeus.

In addition to the bases of the bronze statues which once graced the Stadium, dozens of fragments of those statues have been discovered. They include fragments of hair (BR 474, 477, 596, 553,602), eyelids (BR 475 and 483), wrist (BR 467), and hip (BR 417). Athletic gear includes a fragment of a jumping weight, or halter , of stone (ST 626); bronze strigils (BR 729 and 857), one with the stamp of a horse and rider shown enlarged in a photograph on the central island; and an aryballos (P 436). From the equestrian events come an iron bit (IL 386); a number of gearlike spools from "snaffle bits," designed to prevent the horse from taking the bit in his teeth (BR 357, 457, 544, 940); and a bronze plaque which must once have been attached to the statue of a horse dedicated by its victorious owner (BR 1098; photograph on central island). The forms of the letters on the plaque indicate that it came from the city-state of Sikyon around 500 B.C. The plaque says that the statue of a horse was dedicated to Zeus.

Case 9:

Wells and Their Contents

Nemea is a difficult and frustrating site to excavate. Unlike city-states with continual habitation and a fairly uniform buildup of layers of construction or destruction or habitation debris, Nemea was occupied only once every two years for a few days or weeks at the most. In the meantime the weeds grew up, and with the advent of the games it was necessary to chop them down (thus retaining the same basic ground level), whitewash the buildings, and generally clean up. Since such activities inevitably destroyed the layers on which archaeologists depend, the wells which were not so easily cleaned up are particularly important to our understanding of the history of Nemea. The results of the excavation of two wells are pre-

sented here, both in the region between the oikoi and the Xenon (15 on the model).

As can be seen in the photographs on the panel to the right of case 9, the excavation of a well is tricky and potentially dangerous. Once the fill has been removed to a depth of roughly 2 m., a means must be set up to pull out the excavated earth and to lower and raise the well digger. For these purposes excavators at Nemea use the time-honored windlass, once standard equipment for every village house. The rubble walls of the well must be examined constantly and consolidated from time to time. The greatest difficulty comes at the depth of the water table, where a pump must work alongside the digger. At that point a safety line for the digger, a line from which the pump is suspended, the cord providing power to the pump, the hose bringing the water out of the well, and the line with which the excavated mud and antiquities are removed must enter the mouth of the well together. The digger must be willing to endure cramped, dark, wet, cold quarters. The information retrieved, however, justifies the effort.

The bottom shelf of case 9 displays some of the discoveries from a well designated L 17:1, a cross-sectional drawing of which is on the wall left of the case. This drawing shows that relatively few artifacts lay in the upper several meters of dosing fill, but among them were the inscription (I 104) from which we learn that in 311 B.C. Demetrios Poliorketes, one of the successors of Alexander the Great, established a league, probably modeled on that of Philip (see the discussion of case 3, p. 23), which was to meet at Nemea.[29] Not until the excavation reached a depth of more than 8.50 m. from the ancient ground surface was a level of use encountered in the well. Such levels are characterized by drinking cups and especially by larger vessels which were lowered down the well to fetch water but broke and remained there whole or, more fre-

[29] D.J. Geagan, "Inscriptions from Nemea," Hesperia 37 (1968) 381-84.

Fig. 12.

Kore head on handle of bronze hydria (BR 379).

quently, in parts. This level of use produced, among other items, the large amphora (P 411) which stands to the left of case 9, a saltcellar (P 282), and a spouted jug (P 412).

Below this level of use came a destruction/cleanup level, as is most clear from the terracotta sima, or roof gutter, with a corner lion's head waterspout for directing rain water away from the building it adorned (AT 55). This piece is of considerable intrinsic architectural interest (a plug on its bottom surface is visible in the photograph on the panel to the right); it also tells us that a building at Nemea was damaged or destroyed and its elements thrown away. The same must be true of the building to which belonged the monolithic limestone column with a high square base (A 115), also found in the destruction/cleanup fill; the column now rests to the right of case 9. The cleanup occurred near the end of the 5th century B.C. ; from it the drinking cups also come (P 290 and 291) and perhaps the bases for bronze Vessels (BR 378, 380, 381).

The most notable discovery at this level of the well was the bronze hydria (Fig. 12) displayed in CASE 8, with photographs

on the panel to the right. The female head on its handle allows us to date it originally to the late 6th century B.C. , while the later inscription on its rim ("I belong to Zeus at Nemea") makes it clearly a possession of the sanctuary.

Below this level came a level of use which produced such pottery as a skyphos (P 278), a ribbed lekythos (P 292), and an oinochoe (P 276), all from the second half of the 5th century B.C. Below this the well ended at a depth of 9.95 m.

The top shelf of case 9 presents material from another well, located fairly close to the one represented on the bottom shelf. The second well, labeled L 17:2, was located immediately north of the baptistry of the Early Christian Basilica. Unlike its neighbor, L 17:2 either remained open in its upper levels or was cleaned out in the 5th or 6th century after Christ, for it was used as the ultimate destination of water drained from the baptismal font. A level of use was encountered about 7.50 m. below the mouth of the well (see the cross-sectional drawing on the panel to the right) which produced material of the second half of the 4th century B.C. , including an amphora (P 400) and a mug (P 399). Immediately below this level came one of destruction/cleanup which produced a terracotta sima (AT 75) from the same unknown building as the example in L 17:1. Other material, such as the amphora handles stamped with a palmette (P 401 a-b), establishes a date late in the 5th century B.C. for this level. Immediately below came another level of use, from the second half of the 5th century, with material such as the lamp (L 45) and a skyphos (P 397). Below this the well ended.

These two wells reveal a strikingly similar history. Both were constructed in the second half of the 5th century and were used for a relatively brief period; near the end of the same century both were filled with the debris of a destruction or a cleanup following a destruction. Then for more than half a century—until the last three decades of the 4th century—neither well shows evidence of any activity. Before long,

both wells were closed and put out of use. These data are significant because they suggest that for more than the first half of the 4th century B.C. the Sanctuary of Zeus at Nemea was not being used; that is, the Nemean Games were not at Nemea during that period.[30] The suggestion is reinforced, moreover, by the lack of artifacts of the first half of the 4th century over the whole of the sanctuary. Virtually none of the coins or the pottery, for example, can be dated to that period. A picture thus emerges of a destruction (see further at case 19, p. 61) in the late 5th century B.C. , followed by some two generations of silence and desolation at the Panhellenic center of Nemean Zeus.

The PANELS TO THE LEFT OF CASE 10 take us to the later history of Nemea. At the upper left is an aerial view of the Early Christian Basilica (see Fig. 25), which dates from the 5th or, more likely, early 6th century after Christ. This church, the centerpiece of a settlement which grew up among the ruins of the old Panhellenic sanctuary, is the most prominent monument of that time in the area, although the basilica on the crest of the Evangelistria Hill is of similar date (see p. 80 and n. 46). At the lower left of this panel a photograph shows a detail of the baptistry, with its tile paving, and the sunken font from which came the larger fragment (mended from four joining pieces) of the marble ritual dining table displayed on the center island (A 185).[31] It had been reused, upside down, as the paving of the font, as can be seen in the photograph on the southern side of the center island. Another

[30] That Nemean Games did take place, albeit not at Nemea, is shown by a number of references, including those to the victories of athletes such as Damiskos of Messene, Eupolemos of Elis, Hegesarchos of Arkadia, Sostratos of Sikyon (Pausanias 6.2.9, 6.3.7, 6.12.8, and 6.4.1-3, respectively) among many others during this period.

[31] For similar tables and their probable purpose in the ritual feast called the agape, see G. Roux, "Tables Chrétiennes en marbre découvertes à Salamine," Salamine de Chypre IV (Paris 1973) 169-74; and J. Marcadé and G. Roux, "Tables et plateaux chrétiens en marbre découverts à Delphes," Etudes delphiques (BCH suppl. 4: Paris 1977) 455-57.

piece, probably from the same table, was found in the house attached to the southwestern comer of the Basilica. On the bottom surface of that piece is a ligature (shown in a photograph on the western side of the island) which might be interpreted as reading NEOF YTOY, "belonging to the born-again."

At the top of the panel closer to case 10 is a photograph of a typical area within the Sanctuary of Zeus. It is filled with relatively long and narrow trenches created in the Early Christian period for agricultural purposes. The vegetable gardens of modem Greece offer a precise analogy, but the more ancient version was responsible for considerable destruction of the site at Nemea. Below this photograph is another, showing the rubble walls of a large house built at the southwestern comer of the Basilica (cf. Figs. 28 and 29). It is dearly an architectural dependency of the church, a kind of rectory or parsonage.

Case 10:

Roman and Medieval Pottery

The top shelf, left, displays pottery from the Stadium tunnel, apparently used by people seeking shelter during the first two decades of the 1st century after Christ, before the water channel was put through (see p, 36). The deposit included a plate of the so-called Pergamene ware (P , 365), two-handled mugs (P 467-469), a bowl (P 466), and lamps (L 36 and 38).

The top shelf, right, contains material from a well near the Temple of Zeus (K 14:3 just north of K 14:4 in case 18; see the photograph there), including bowls (P 345 and 346); a bronze bucket, or situla (BR 587); and lamps which show a bust of Athena (L 42) and the infant Herakles (L 41). This deposit from the late 3rd or early 4th century after Christ offers the only substantial evidence of activity at Nemea after the 2nd century B.C. and before the Early Christian settlement. It would appear that at this time activity was isolated at this well, which was cleaned out and deepened (cf. p. 128).

The bottom shelf, left, of case 10 presents typical pottery of the Early Christian period at Nemea (5th and 6th centuries after Christ). Particularly characteristic are the jugs (P 279 and 545) and the lamps, including L 125 with its cross in the top disc.

On the bottom shelf, right, are typical examples of Byzantine pottery of the 12th and 13th centuries, among them a glazed oinochoe (P 1192), a small glazed bowl with a sgraffito animal (P 164), and a handle stamped with the eagle of Constantinople (P 1238).

Black and white photographs on the WALL TO THE RIGHT OF CASE 10 show a typical Early Christian cemetery before and after the graves were excavated. This cemetery was located just south of the Temple of Zeus, but others have been found at the northwestern corner of the Temple, midway between it and the Bath, and especially around the Basilica.

The three small marble columns (A 110-112) on the LOW BASE near the picture window may have been part of the iconostasis of the Basilica.

Case 11:

The Early Christians

Several artifacts here reveal details about the life of the Early Christian community at Nemea. At left is material from grave 7 in the cemetery at the northwestern corner of the Temple of Zeus. The two color photographs on the wall to the left show that this simple, typical grave was formed by setting roof tiles on edge along the sides and leaning them together at the top. Within the grave was the skeleton, together with more gifts than are typical (Fig. 13), including a bronze pin (GJ 49); a pair of ear spoons (BR 828 and 829), behind the head in the photograph; a pair of cosmetic spatulas (BR 830 and 856); a stone cosmetic palette (ST 518) found on the breast of the deceased; and a silver-plated bronze finger ring with an enigmatic monogram (GJ 66) which had stained the bone of the ring finger. The grave is dearly that of a relatively

Fig. 13.

Grave 7 during excavation.

wealthy woman. Analysis of the skeletal remains indicates that she was young—about seventeen years—and suffered from anemia, a common ailment among the inhabitants of the settlement.

The center of case 11 has various personal effects from many other graves: finger rings (GJ 90, I , 96, etc.), belt buckles (BR 721, 832, etc.), and crosses which could, in some cases, be folded up and concealed (GJ 84 and 85). The medallion of St. George and the dragon (BR 38) comes from the later Byzantine period. Glass goblets were common in the Early Christian settlement, but they were so thin that only their bases have survived (GL 24-27, etc.). The floor of the church (see the photograph of the baptistry on the panel to the left of case 10) was paved with baked tiles. One example in case 11 (AT 73)

was marked by the manufacturer, who stuck his fingers into the wet clay. Early Christian trademarks were not complicated. The square bronze rod (BR 988) is actually calibrated with marks; it was the beam of a steelyard, or weighing scale, similar to the modern example in the photograph on the eastern side of the CENTER ISLAND .

The right (southern) side of case 11 is concerned with the end of the Early Christian settlement. This story, repeated throughout the Nemea valley, can be told succinctly from the discovery of animal bones, cooking pots (such as P 368), and a hoard of bronze coins (C 1509-1531, 1246) inside the entrance tunnel of the Stadium. At a date in the 580s after Christ, the tunnel, which had been silted shut at its ends but had a dear space some four feet high within, was entered after the removal of two voussoir blocks from its eastern end. A person or persons lived there for some little time (several days at least, to judge from the quantity of animal bones), and it must have been then that the graffito shown in the photograph on the wall was scratched: AIQ EPIZW HS , "ethereal life," seems an appropriate sentiment for an Early Christian. The owner of the coins, which range from the time of Justinian I (C 1510 from A.D. 539/40) to that of Justin II (C 1523 from A.D. 576/7), did not return to claim them, falling victim, with the whole settlement, to the violent invasion of Slavic tribes at a date established from other parts of the excavations as no earlier than about A.D. 582. There was no recovery. For ages thereafter the archaeological picture at Nemea is very dark.

The EASTERN END OF THE MAIN EXHIBITION HALL is now devoted to the display of prehistoric artifacts. In due course these will be moved into the east wing and more material from the Sanctuary of Zeus displayed here. For the moment, however, the prehistory of the region is in this part of the museum.

Near the picture window is a pair of PANELS , the northern one of which shows a general view of the Nemea valley from

the east. West of the Sanctuary of Zeus the long, low hill called Tsoungiza can be seen, running from north to south like a spine through the valley. From the picture window the northern end of this hill (which has no antiquities) can be seen to the extreme left (west). Although scattered traces of prehistoric remains have been discovered in other parts of the valley, including the Sanctuary of Zeus, concentrated prehistoric remains have been found exclusively on this hill. (The configuration of the valley is such that Tsoungiza offers a direct view of the citadel of Mycenae some 11 km. to the southeast.)[32]

Case 12:

Neolithic and Mycenaean Pottery

The top shelf displays a collection of pottery from an Early Neolithic (6000-5000 B.C. ) pit, probably a refuse dump, from Tsoungiza. Even though no architectural remains of the settlement of this period have been recovered on Tsoungiza, the quantity of pottery, of which this is a very small sample, shows that there was habitation of considerable size and duration. The two most characteristic pottery types from this period are those known as black ware, which has a highly polished black or dark gray surface (e.g., P 916, 930, 915, etc.), and rainbow or variegated ware, which tends to have pink or buff or orange at the top, gradually darkening through gray to black at the bottom, both outside and in (e.g., P 929, 79, etc.). The most common shape is the deep bowl, usually with

[32] Excavations on the Tsoungiza ridge were first carried out in 1925 and 1926; cf. C. W. Blegen, AJA 31 (1927) 436-39; J. P. Harland, "The Excavations of Tsoungiza, the Prehistoric Site of Nemea," AJA 32 (1928) 63; and C. W. Blegen , "Neolithic Remains at Nemea," Hesperia 44 (1975) 251-79. The University of California at Berkeley next excavated there in 1974, 1975, 1979, and 1981; see appropriate annual reports in Hesperia and J. C. Wright, "Excavations at Tsoungiza (Archaia Nemea), 1981," Hesperia 51 (1982) 375-97. At the invitation of the University of California, Bryn Mawr College excavated on the hill from 1984 to 1986. The material from these latest excavations remains to be added to the museum exhibition.

Fig. 14.

Vessels from house on Tsoungiza (P, 685, 723, 724, 740, 708, 716, 722).

a ring base or foot, although some have rounded or nearly pointed bottoms. The least common shape is the askoid jug (P 920) with a rounded bottom and an ovoid body painted with red parallel zigzag lines. The large fragment of a collar-necked jar (P 931) is unusual for its decoration: the lower part was painted solid red while the upper part of the body bears two rows of elongated triangles painted in the same red.

With such examples from the thousands of vessels recovered from Early Neolithic deposits on Tsoungiza it becomes clear that this early phase of human activity in the Nemea valley was rich and lively.

On the bottom shelf, left, of case 12 are several vessels from the floor deposit of a house on Tsoungiza (Fig. 14). To the left of the case is a photograph of that house with many of the vessels still in place at the time of excavation. Comparison of the pottery with that from other sites, notably Grave Circle B at Mycenae, indicates that it dates from the Middle Helladic IIIB period (perhaps about 1550 B.C. ). Typical and related shapes are the angular bowl or goblet (P 716) and the double-handled kantharos cup (P 708 and 722). The fabric of the spouted beaker (P 723) is related to these. All are of the

type traditionally known as yellow Minyan. Another interesting shape, of a fabric with a greenish tint, is the ladle (P 685).

Evidence of burning in the house (some but not all the fragments of vessels like P 708, 716, 724 are burnt) suggests the occurrence of a destruction which shattered the vases, followed by a fire. The absence of signs of violence indicates that natural rather than human agency caused the destruction. It also seems dear that up to the point of that destruction, human activity had been increasing at Nemea even if the settlement had not attained anything like the wealth of nearby Mycenae.

On the bottom shelf, right, of case 12, are artifacts from the successor of the Middle Helladic settlement. These date from the Mycenaean or Late Helladic period (about 1500-1200 B.C. ) and include a kylix (P 137), a tripod krater with its bottom pierced for straining (P 75), a ladle (P 85), painted cups (P 78 and 518), and a stirrup jar (P 1407). Once again this is part of the evidence which suggests that Nemea had a small but thriving community during the last phases of the Bronze Age.

On the WALL ABOVE CASE 13 is an aerial photograph taken in 1977 of the Tsoungiza Hill. The houses of the modem village of Archaia Nemea are at the bottom (south); the main prehistoric site of the hill is southwest (below and to the left) of the two chicken coops marked C.

Case 13:

Prehistoric and Geometric Artifacts

The left side of case 13 is devoted to material other than pottery groups from the prehistoric period at Nemea. Some of it comes from the area of the Sanctuary of Zeus, but most is from Tsoungiza. It includes many tools such as stone grinders (ST 8, 10, 308, etc.), stone ax heads (ST 289, 2, etc.), and obsidian blades (ST 4, 265, 576-583). From the late Bronze

Fig. 15.

Bronze dagger (BR 17).

Age (the Mycenaean period) come the ivory sword pommel (BI 1), the group of terracotta figurines (TC 4, 10, 11, etc.), and the bronze dagger with a bone handle (Fig. 15). Finally there are a few sherds of pottery from the Early Helladic period (roughly the third millennium B.C. ) such as P 90, 91, 1370, and so forth. Although this evidence shows clearly that there was human activity at Nemea in the early Bronze Age, it is equally dear that the activity was more limited than that in some earlier and later periods.

The right side of case 13 shows the faint beginnings of activity in the Nemea valley after the hiatus known as the Dark Ages (roughly 1100-700 B.C. ). With the fall of Mycenae and the end of Mycenaean civilization in Greece (ca . 1150 B.C. ) human activity throughout the Balkan peninsula seems to have been much restrained, and the population seems to have dwindled. Not until the 8th century B.C. did Greek civilization begin the renaissance which culminated in the Classical period (480-323 B.C. ). Nemea seems to have participated in this reawakening in a limited way. A few examples of fragmentary pottery of the 8th century B.C. have been found close to the Temple and the Altar of Zeus (P 87, 123, 781, 803). These show the characteristic geometric decorative patterns which give the period its name. From this same Geometric period, but discovered in fill washed into the Stadium from the hill above, comes a bronze horse (Fig. 16). A few examples of pottery (P 779 and 380) also date to the 7th century B.C. , but dearly Nemea flourished only with the establishment of the games in the 6th century B.C. The traditional date of 573 B.C. coincides well with the evidence of increased activity in the Sanctuary of Zeus.

Fig. 16.

Bronze geometric horse (BR 20).

The SOUTHEASTERN CORNER OF THE MAIN EXHIBITION HALL is devoted to material discovered by the Archaeological Service of the Ministry of Culture in the valley of ancient Phlious, or modern Nea Nemea, west of the ancient Nemea valley (see the map in the courtyard or Fig. 1)—a broad fertile valley that could support a considerable population. The southern panel on the island reminds us (with a text in modern Greek) of other sites known from ancient authors in this valley drained by the Asopos River, which flows northward to the Gulf of Corinth. Chief among these sites was Araithyrea, which was known to Homer (Iliad 2.571) and Pausanias (2.12.5). Strabo (8.6.24) tells us that the inhabitants of Araithyrea abandoned their town to found Phlious 30 stadia (about 5 km.) away.

Two ancient sites, excavated to varying degrees, might be identified with Araithyrea. One is on the low hill of Aghia Eirene to the left of the road from Nea Nemea to Stymphalia.[33] The foundations of Mycenaean or Late Helladic houses have been discovered here as well as tombs from the end of the Middle Helladic period, one of which is shown during excavation in the photograph to the right of the text on the panel.

The second site is represented by several dozen rock-cut tombs discovered in the modern town of Aidonia, which lies further along on the road to Stymphalia.[34] The tombs themselves have architectural interest, with their long dromoi , or entrance passageways (see the photograph on the panel to the right), and their interiors carved out of the soft bedrock to imitate the interiors of houses. These were family tombs in which corpses were buried with pottery, gold jewelry, ivory-inlaid furniture, and so forth. The animals carved on seal stones tell something of the inhabitants' lives, and the scenes on their gold sealing rings tell of their religious liturgies. The scarabs show the existence of trade with and influence from Egypt. Finally, deposits of Geometric pottery show that their descendants continued to venerate the burials made long ago.

Case 15:

Jewelry From Aidonia

The material in this and the next three cases has not been formally published. Photographs are therefore not allowed, and the following descriptions are necessarily summary and superficial. Case 15 contains material from various tombs at Aidonia: (from left) necklaces, seal stones, gold sealing rings; scarabs, ivory discs once inlaid in wood, gold sew-on rosettes

[33] To be published by Z. Aslamantidou.

[34] To be published by K. Krystalli-Votsi.

which adorned the clothing of the deceased, bronze and stone arrowheads, stone spindle whorls, and a bronze sword.

Cases 14 and 16:

Pottery From Aidonia

These two cases display a number of the vases from the Aidonia tombs—only a sample from these rich burials.

Case 17:

Pottery From Aghia Eirene

The relatively plain pottery and the terracotta animal figure on the upper right shelf are from the excavations at Aghia Eirene, shown in the photograph mounted on the panel behind the case. Everything else in case 17 comes from the tombs of Aidonia. On the panel to the right is a photograph of one of the Aidonia tombs during excavation.

Case 18:

A Nemean Well and Aratos of Sikyon

This case and the material against the south wall of the room behind it represent the excavation of another well in the Sanctuary of Zeus. Called K 14:4, it is shown in a cross-sectional drawing on the panel to the east (right). It is the nearer of the two wells close to the southwestern corner of the Temple of Zeus, as shown in the photograph on the adjacent panel. (The further well is K 14:3 in case 10; on the site, see p. 128.)

Well K 14:4 was covered with stone slabs at the time of discovery. The uppermost 1.66 m. were empty; the next 3.60 m. were filled with sandy earth containing few artifacts, although two coins found therein are of interest: C 1310, a bronze issue of the Arkadian League of the late 4th century B.C. , and C 1287, a bronze issue of Ptolemy III Euergetes of Egypt,

dated 247-222 B.C. The sandy earth may have been dumped into the well or, more likely, slowly eroded down into it from between the stone slabs.

The next 2.40 m. of the well were as rich in artifacts as the upper fill had been poor. This layer of the well represents a period of destruction/cleanup when inscriptions, architectural members, and other debris were dumped deliberately into it. The inscriptions included three large fragments (against the SOUTH WALL ) recording a treaty between Argos and Aspendos in the late 4th century B.C. (I 75). This inscription clearly points to control of the sanctuary at the time of the treaty by Argos. The stone was broken elsewhere, for no other fragments were found in the well. The stump of the limestone stele of another inscription, still leaded into its stone base (I 76), also came from this level of the well, as did a major portion of an inscribed marble stele (I 85; the photograph on the wall shows this stele moments after it emerged from the well). The text, in two columns, gives the names of places and people who were the theorodokoi , "herald receivers," of the Nemean Games. Every two years when the games were to take place, heralds (theoroi ) would travel throughout the Greek world to announce the time of the games and the sacred truce surrounding them. Upon arriving at a given town, they would be received by a theorodokos , the local representative of the Nemean festival, who would give the theoroi shelter, entertainment, and introductions to appropriate officials. This "support group" was probably organized in about 323 B.C. A related text was also found in the well (I 73 + 29; see top shelf, center, case 18). It records that groups of six (theoroi? ) are to go to various regions of Greece. This inscription, like I 75, must have been broken up elsewhere before being thrown down the well since the smaller of the two joining pieces was discovered in earth fill near the southeastern corner of the Temple of Zeus some 40 m. from the well.

The architectural debris from this well includes a half-finished Ionic-Corinthian column with base (A 146; against the south wall) and, in case 18, painted terracotta simas (AT 69 and 70) and antefixes from the roofs of two different buildings (AT 68 and 78), as well as a fragment of a Corinthian capital (A 147). All this debris suggests that a violent and widespread destruction took place in the sanctuary, a suggestion in no way disproved by the skull of a bull (BI 10), a grinding stone (ST 391), and especially an iron sword with a gold inlaid design near the hilt (IL 296). Mixed in with this debris were bronze rings and attachments from larger vessels (BR 644, 584, 646, 647) and a small bronze locket (BR 648). Pottery such as the lekanis (P 388), bowl (P 381), skyphos (P 382), and askos (P 384) shows that the destruction/cleanup must have taken place in the second half of the 3rd century B.C. This date is confirmed by the silver coin of Sikyon (C 1288), 250-146 B.C. , and the bronze coin of Ptolemy III Euergetes (C 1314), 247-222 B.C. A third bronze coin of Corinth (C 1313) cannot be dated so closely, although it dearly belongs in this general period.

At a depth of about 7.66 m. from the mouth of the well, the fill ceased to contain this heavy debris and instead had objects more appropriate to the use of the well as a source of water. This layer, only about 0.20 m. thick, produced two handles (BR 653) from a bronze bucket, or situla, and the bases of two bronze vessels (BR 651 and 652). Another Corinthian bronze coin (C 1312) only generally dates this use of the well, but the pottery, such as a mug (P 386), a kantharos (P 383), and a blisterware jug with impressed ivy-leaf decoration (P 389), belongs to the second half of the 3rd century B.C. , though to a period dearly and necessarily earlier than that of the material in the layer just above.

The final 0.15 m. of the well also produced several elements of bronze vessels: a rim (BR 649), a handle (BR 654), and four bases (BR 650, 652, 656, 657), again indicating a period of

use. The date of this use which emerges from a fish plate (P 391) and a cup-kantharos with stamped decoration on its floor (P 385) is the late 4th century B.C.

All these data together give us the history of both the well and the Sanctuary of Zeus at Nemea. The well was constructed in the late 4th century B.C. , at the same time as many other buildings (the Temple of Zeus, the Stadium, the Xenon, the Bath, etc.). Clearly this is the time when the games returned to Nemea, probably under Macedonian influence (see case 3, pp. 22-23). Then a gap in the use of the well reflects the shift of the games from Nemea to Argos, which appears from other evidence in the sanctuary to have occurred in the 270s B.C. Next comes a period of use in the second half of the 3rd century which must reflect renewed activity at the site, followed by a cleanup after a violent destruction. Written sources tell of an episode in the history of the Nemean Games which can explain these data. Aratos of Sikyon, at odds with Argos, reestablished the Nemean Games at Nemea in about 235 B.C. and blockaded those which took place the same year at Argos.[35] Any athlete who insisted on participating in the games at Argos was captured and sold into slavery, in obvious violation of the sacred truce. We do not know how many years Aratos's games took place at Nemea, for when Aratos later became allied with Argos, the "alternate" games were disbanded; but the second use of the well can safely be associated with the reestablishment of the games at Nemea. The violent destruction would have resulted from this episode, and the Argive inscriptions may have been deliberately broken up by the Sikyonians and the buildings destroyed either by them or by the returning Argives, who dumped the material down the well, thus effectively cutting off the water supply of the sanctuary and making imitations of Aratos's alternate games in the future difficult at best. As we shall see

[35] Plutarch, Aratos 28.3-4.

shortly, this was not the only time when violence entered the sacred "apolitical" Panhellenic festival center.

Case 19:

The Early Temple of Zeus and Violence at the Nemean Games

This section of the exhibition deals with the Early Temple of Zeus and its destruction. As will be seen at the site itself, the Early Temple lies completely under the 4th-century Temple of Zeus and has been almost completely obliterated by it. Nonetheless, the architecture of the building has not been completely lost. The 4th-century Temple cuts through layers of limestone working chips which lie north and south of it; these layers date from the 6th century B.C. and thus predate and are irrelevant to the 4th-century Temple. The sixth-century date is appropriate for the temple of a festival organized in 573 B.C. The bottom shelf, left, of case 19 holds several fragments of roof tiles from that initial period of the Early Temple. These include fragments of hip tiles (AT 95 and 232) and pan tiles with the stamps of manufacturers on them: rosette (AT 245), "key hole" (AT 205), and "S" (AT 224). On the shelf above these pieces are a Corinthian cover tile with notches cut out at one end (AT 106) and antefixes (Fig. 17) with impressed decoration on the front (AT 82 and 91; rosettes are stamped on their upper surfaces).[36] These elements have been put together to reconstruct the roof of the Early Temple as it appeared at the western end. The life-sized MODEL OF THE ROOF near the door to the courtyard (note the drawing on the wall above) shows a regular Corinthian tile system with large square pan tiles the joints of which are protected by peaked, rectilinear cover tiles. The Early Temple, like many temples

Fig. 17.

An impressed terracotta antefix from the Early Temple of Zeus (AT 91).

of this period elsewhere (notably at Isthmia and at Corinth)[37] but unlike temples of later date, did not have gables or pediments at both ends; rather, its western (back) end was enclosed by a hipped roof. The handing of the oblique joint between the side and end roofs differed from site to site, but here at Nemea the solution was simple: during manufacture, while the day was damp, a Corinthian pan tile was bent on the diagonal to accommodate the adjacent pan tiles on each side. The drawing and the model show how this system worked. Extant tile fragments are indicated in red-orange on the model and their inventory numbers noted. Many of them are on display in case 19.

In the middle of the top shelf is another curiosity of the Early Temple: a fragment of cement with a stucco coating on one side (AT 173). Many such fragments have been found with the debris of the Early Temple, and it is not known whether they came from the floor or the walls or some other part of the building. Clearly, however, the Greeks of the

[37] O. Broneer, Isthmia I, Temple of Poseidon (Princeton 1971) 40-53.

6th century B.C. knew how to make and use cement because a similar cement adheres to the undersurface of the original tiles, for which it seems to have served as a bedding. (Such cement should be distinguished from the structural concrete of the Roman age.)

The top and bottom shelves, right, of case 19 hold fragments from the ridge akroteria which once sat on the roof of the Early Temple (Fig. 18). As can be seen from the pieces on the bottom shelf (AT 117 and 119), the base of these akroteria consisted of a Corinthian cover tile bent down at either end to follow the adjacent sloping sides of the roof. The finial resting on this base was painted vividly on both sides with a double volute above which was a palmette with alternating deep red and black leaves (compare with the drawing on the wall to the right). The heart of the palmette was cut out so that when it was in position on the peak of the roof, blue sky was visible at its core. Although these akroteria were discovered with the other roofing materials of the Early Temple, their style indicates that they were part of a late Archaic (perhaps ca . 500 B.C. ) repair or refurbishing of the Early Temple.

In addition to these elements, dozens of limestone blocks from the Early Temple have been found at Nemea, both in the destruction debris of that building and, reused, in later construction (e.g., as wellheads L 17:2. and K 14:3, in cases 9 and 10). These blocks are characteristically 0.31-0.32 m. high, 0.88 m. wide, and 0.92-0.93 m. long. Near one end of the top surface is almost always a set of "ice-tong" holes used to lift the stone into position during the construction of the Early Temple. On the BASE TO THE RIGHT OF CASE 19 are two blocks from this series (A 163 and 171). One of them (A 163) preserves the lifting holes, and both have been cut down to receive wooden beams. Presumably these blocks came from near the top of the wall.

Like many other elements of the Early Temple, these two blocks have been badly burnt and broken, and one can see

Fig. 18.

Reconstructed ridge akroterion from the Early Temple of Zeus.

how the stone has been blackened by fire. Two photographs on the wall above them show part of the destruction debris of the Early Temple. On the top shelf, center, of case 19 are two examples of the twisted and vitrified tiles of the Early Temple which have also been found in this debris (AT 93 and 115). They show clearly the violent end of the Early Temple. In addition, these layers of debris have produced many bronze arrowheads, some of which are displayed here (BR 77, 113, 162, etc.), and iron spear points and butts (IL 116, 174, etc.). These show with equal clarity that the cause of the destruction was a pitched battle whose date, on the basis of pottery in the debris, can be assigned to the final quarter of the 5th century B.C. , probably in the period 415-410 B.C.[38] Another

[38] Although no ancient author records such a battle, Thucydides does attest to extensive military maneuvering in Nemea and its environs in 419/8 B.C. (5.58-60) and again in 415/4 B.C. (6.95). These seem the likely years when control of the Nemean Games, and of the Sanctuary of Zeus, passed from Kleonai to Argos. On this question see S. G. Miller, "Kleonai, the Nemean Games, and the Lamian War," Hesperia , suppl. 20 (1982) 100-108.

consequence of this battle was almost certainly the removal of the Nemean Games from Nemea until the 330s B.C. (cf. case 9, p. 43). Thus once again archaeological evidence has revealed political violence in the ancient Panhellenic centers.

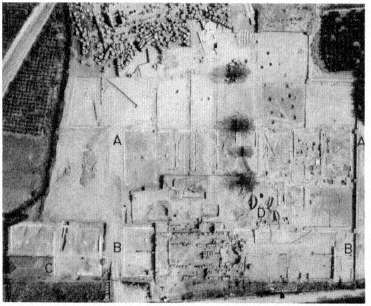

On the SOUTH WALL to the right (west) of the door to the courtyard and on the panels beyond are details of ancient activity on the south side of the Sanctuary of Zeus, as shown in the photograph at the top of the northernmost panel. This aerial view (Fig. 19), taken in 1984, shows the outlines of the foundations of the oikoi (A-A), of the Xenon (B-B), the Bath (then with a shed over the bathing chamber, C), and a unit of kilns (D). It also records the pits in the floor of Oikoi 8 and 9 and in the area south of them.

On the bottom of this panel is a photograph of one room in the Xenon with a stone-paved hearth (see Fig. 32). More will be said about this building during the discussion of the site.

The central panel displays photographs of the bathing chamber of the Bath during its original excavation in 1924. On the right is a view of the eastern tubs. On the upper left is a detail of those tubs, and on the lower left a more general view, with the steps down into the chamber on the left, a column drum, and—to the right at middle ground—some of the parapet slabs which will be seen in the Bath itself.

Photographs on the panel to the left, near the south wall, show the water reservoirs south of the Bath at the time of their discovery in 1982. These too will be visible at the site.

Sometime during the third quarter of the 5th century B.C. , Oikoi 8 and 9 and the area south of them were taken over by a bronze sculptor. The pits visible in the aerial view of the south side of the sanctuary are the remains of his workshop. On the south wall near the last panel are two color photographs of this site. Here, at the top, was the furnace where he melted bronze before pouring it into his molds (see Fig. 59). The lower photograph shows one of these molds (TC 59) still in place in the pit. The large stone basin here, also from the

Fig. 19.

Aerial view of the south side of the Sanctuary of Zeus, 1980.

workshop (ST 362), was apparently used to mix clay for the molds.

Case 20:

Industry and Technology

On the left are artifacts from the sculptor's workshop. Three terracotta molds are displayed: TC 60, for the shoulder of a statue at the neck; TC 59 for an arm; and TC 57 for the drapery on a relatively flat part of the upper body. The statue was made in pieces (legs, arms, feet, head, etc.) by the lost-wax process; fragments of such pieces are in cases 6 and 7. A core was made of clay with a skeleton of iron armatures such as IL 39, 42 a-b, and 49 here. Wax was applied to this core and shaped as desired. Details were worked out with tools like the

pointed stone inscriber (ST 342). Damp clay, perhaps after an initial working in a lekanis like TC 192, was applied over the wax, forming a negative impression of it. The whole was then set into its own pit, where a fire around the mold baked the clay and melted the wax, which flowed out of a hole left for the purpose. The molten bronze poured into the space left by the wax cooled and hardened in the shape originally formed by the wax. The molds were broken and the bronze pieces removed to be soldered together with lead from ingots such as IL 31. The bronze was then worked over with tools such as the chisels, drills, and hammer found in the workshop (IL 11, 12, 14, 15, 60, 476) and smoothed and polished with stone grinders such as ST 341. After the finished statue was leaded into a base (like those previously seen on the north wall near case 7), it was dedicated to Zeus.

Photographs on the SOUTH WALL of the room show the complex of kilns along the north wall of the Xenon and east of the Basilica (see the aerial photograph on the first panel above). The first photograph is a general view of the kilns from the west. The north wall of the Xenon is marked B at the right; the nearest of the kilns is a circular example marked K . In the distance is the settling tank for clay, marked S . Between K and S are two more kilns, both rectilinear, with the southern one (L ) the better preserved. The next photograph shows the rectilinear kilns from the north with the settling tank (S ) at the left. Note the steps which lead down into it. Kiln L , with the firing-chamber floor preserved, is in the middle ground; the north wall of the Xenon cuts through it. The third photograph in the series, in color, shows the entrances to the stoking chamber of kiln L . Both this kiln and the less well preserved one to the north had stoking chambers entered by a common sunken area where fuel was stored. The next two photographs show kiln L from the south and from above (west). Finally, a drawing by C. K. Williams (Fig. 20) shows kiln L as discovered (upper left) and with the firing chamber partially restored (upper right).

Fig. 20.

Kiln, by C. K. Williams.

All these kilns belong to the last thirty years of the 4th century B.C. and were used exclusively, so far as the materials found in them allow us to say, for the manufacture of roof tiles. In case 20 (center) are examples of the tripod stacking dividers (TC 14 and 22) which allowed the hot air of the firing chamber to circulate between the stacked tiles, baking them evenly. The fragment of another such divider made in the form of a finger (TC 13) reveals a certain humor, perhaps born of the tedium of making hundreds of such dividers. Beside this are examples of wedge separators (TC 15, 21, 23) used to keep the stacks of tiles separate from one another. These kilns

were used to make the tiles of the 4th-century Temple of Zeus, the Bath, the Xenon, the houses south of the Xenon, and (we may assume) other buildings still to be discovered. They seem to have been laid out slightly in error, since the Xenon cuts through the one kiln (L ), and the circular kiln west of it was apparently built after the construction of the Xenon was under way—to finish the job. This extensive complex shows, first, that there was a massive construction program in the final decades of the 4th century at Nemea—the time when the games returned to Nemea and such a program would have been necessary. The massiveness of the program speaks vividly to the funding poured into the effort; the suggestion (see p. 23) that the Macedonians were responsible seems inevitable. Who else at that time could have mustered such funding? The construction complex shows, second, that roof tiles were made on the spot for construction projects, not ordered ready-made from a central supplier. This situation, though it differs from the modern one, is logical in view of the problems of transport and breakage. It would have been much easier to import clay to Nemea than to have brought in ready-made tiles.

In case 20, right (east), is a series of tools from another workshop, which, like the kilns, was between the Xenon and the oikoi , but further west, just north of (and partly covered over by) the narthex of the Basilica. Here were informal pits filled with chips from the working of Pentelic marble which was used, so far as is known today, only on the sima of the 4th-century Temple of Zeus. It may well have been here that the sima was carved (see the courtyard, northeastern corner). Bronze tweezers (BR 49 and 908) found here would have been useful in such an operation, nor is the ivory stylus (BI 13) out of place. That the work which took place here was specifically sacred is attested by the lead sheet (IL 279) once nailed to the end of a wooden beam or something similar. It bears the inscription IEPO(Y), "of the sanctuary." The black-glaze

plate with stamped decoration and rouletting on its floor (P 370), the bowl with similar decoration (P 369), and the two lamps (L 39 and 40) which were found with the marble chips date from the period between 350 and 325 B.C. , an appropriate date for the major construction program the centerpiece of which was the Temple of Zeus.

The remaining objects in the right side of case 20 are from the 4th-century Temple of Zeus itself. IL 236 is an iron dowel with some of the lead which held it in place still adhering to it. Blocks in the wall and the superstructure of the Temple were fastened to the block immediately below by means of these dowels. The tools (chisel, point, etc.) were discovered in the layers of limestone chips from the construction of the Temple (IL 308, 377, 505), as were the lead ingots, IL 335 and 242, the second with the enigmatic inscription L AKT.

On the wall to the right between case 20 and the DOOR TO THE COURTYARD is a large terracotta akroterion (AT 42). It features a crowning palmette above intricate volutes in the center of which is a siren. Dating from the first half, and probably the second quarter, of the 5th century B.C. , this akroterion was the central roof decoration of Oikos 9 (a small model of this oikos is beneath the siren).