The Mask As Metaphor

Tlaloc from the Fall of Teotihuacán to Tenochtitlán

What happened to the speculative thought of Teotihuacán during the decline and after the fall in A.D. 750? Evidence of philosophical activity is difficult to detect archaeologically under the best of circumstances, and the widespread social, political, and military chaos that must have resulted has left little record for the archaeologists. Consequently, our understanding of that period is as murky as our understanding of the reasons for the fall of such a mighty society. But in the limited area of our concern with the development of the mask of the rain god, one thing is absolutely clear: Tlaloc survived, essentially unchanged, the fall of the culture that conceived him. Whether that survival was owing to the survival of the priestly tradition of Teotihuacán among those who found refuge elsewhere or to the use of Teotihuacán's symbols by newcomers on the scene eager to legitimize their own power by association with the fallen grandeur of Teotihuacán is uncertain. But whatever the historical process that brought it about, the development of the rain god of the Valley of Mexico followed precisely the same course as the parallel development of Cocijo in the Valley of Oaxaca, although the cataclysmic social changes of the Valley of Mexico have no real parallel in Oaxaca. Fixed in form and meaning early in the Classic period, the symbol system of Tlaloc, like that of Cocijo, remained essentially unchanged.

That stability is remarkable in view of the developments in the Valley of Mexico which brought influences from all over Mesoamerica to bear on the area. According to Diehl, the vacuum created by the fall of Teotihuacán "was soon filled by at least two, and possibly four, centers" in and on the periphery of the valley. Tula and Cholula were most involved, with Tula ultimately gaining the ascendancy, but Xochicalco and El Tajín, as well as Cacaxtla, "reached their highest developments at this time" and played a role in the politics of the region which is not yet clearly understood.[200] That it was a time of ferment is indicated archaeologically by the fact that "these centers ... seem to combine architectural and artistic forms drawn from both highland and lowland Mesoamerica."[201]

At Xochicalco, for example, the pottery recovered archaeologically suggests that it was "the northwestern frontier outpost for a Maya cultural tradition"[202] while "the sculptural style . . . is clearly linked to Teotihuacán, on the one hand, and to Monte Albán, on the other. It also is obviously connected with the 'Ñuiñe' tradition of northern Oaxaca-southern Puebla"[203] associated with the Mixtecs. This sculptural tradition is best represented in two examples from the site. Perhaps best known and certainly the most impressive is the decorative frieze on the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, a frieze depicting undulating feathered serpents within whose coils are interspersed seashells and seated priests wearing feathered serpent headdresses. Although in appearance it is quite different from the frieze on the Temple of Quetzalcóatl at Teotihuacán, the iconographic similarities are unmistakable. It is significant, however, that here the feathered serpent does not share the frieze with Tlaloc.

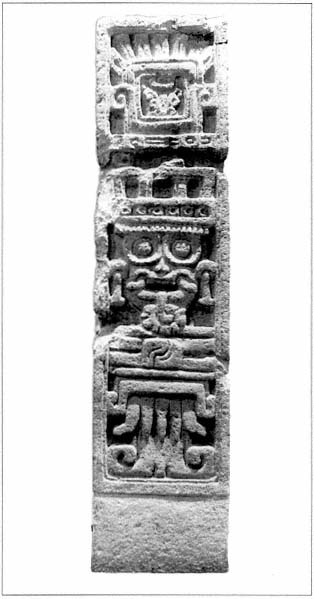

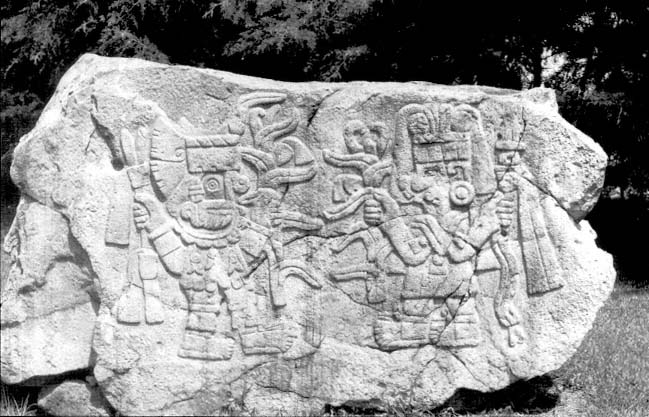

But Tlaloc does appear in the other well-known example of Xochicalco art. In 1961, three stelae that had been ritually broken and interred under the floor of a temple were discovered. Covered on all four surfaces by symbolic motifs and glyphs, each of them has a central face on the front surface. Two of the three depict a face emerging from the

mouth of a jaguar or serpent mask, a mask that, with its bifurcated tongue and that same motif inverted to form nostrils, looks very much like the frontal view of the feathered serpent masks on the Temple of Quetzalcóatl at Teotihuacán. These faces have been widely interpreted as Quetzalcóatl, but the four short teeth with outcurving fangs on either side in the mouth of the mask above the emerging face are those of Tlaloc, as is proven by the other stela, Stela 2 (pl. 21), which displays the mask of Tlaloc, with the same teeth, in its center. This Tlaloc is remarkably similar to the central image of Tlaloc at Teotihuacán in its mouth and teeth, its goggle eyes, and the water lily dangling from its mouth. Like the Tlaloc mask found on urns at Teotihuacán, this mask wears a year-sign headdress, a motif repeated twice on the rear of the stela, and in the only significant difference from the Teotihuacán images, has a pendant dangling from the center of each circular ear flare. To carry the similarity to Teotihuacán a step further, immediately beneath this Tlaloc mask on the lower third of the stela is a representation of the Tlaloc mouth virtually identical to that on the first of the Teotihuacán merlons discussed above (pl. 16). Though this stela, like the other two, "bears columns of glyphs pertaining to names, places, motions, and dates, reminiscent both of Classic Maya and Monte Albán inscriptions,"[204] the Tlaloc it displays as its raison d'être is the Tlaloc of Teotihuacán.[205]

Pl. 21.

Stela 2, Xochicalco (Museo Nacional de Antropologia, México).

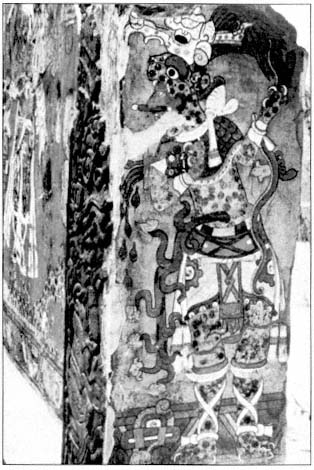

Tlaloc appears in a similar way at the most recently recognized late Classic period site in the region, the fortified, mountaintop center of Cacaxtla celebrated for its two groups of mural paintings discovered in 1975 which are a striking mixture of the styles of Xochicalco, Teotihuacán, Veracruz, and the Maya.[206] One of these two groups is composed of the four murals found in Structure A, each a large painting of a single human figure wearing an animal or bird costume, and in each case the head of the human figure emerges from the open mouth of the animal or bird, a motif we will explore at length in the discussion of the ritual use of the mask. Of particular interest to us at this point is the painting on the north door jamb (pl. 22) of a figure iconographically similar to the Teotihuacán Tlaloc. The man depicted either wears a jaguar costume or is emerging from the open mouth of a jaguar, an ambiguity that results from the fact that the hands and feet of the figure are the paws of a jaguar rather than the human hands and feet customarily depicted when human beings wear costumes in Mesoamerican art. The jaguar head from which the human head emerges itself wears a headdress composed of the upper jaw and head of a saurian creature iconographically similar to the headdress worn by the Sowing Priests at Teotihuacán (pl. 38). The most striking connection with Teotihuacán, however, is that the figure holds a stylized serpent in one hand and clutches a Tlaloc effigy urn from which water flows under the other arm—exactly the accoutrements of the earlier Lightning Tlaloc at Teotihuacán (colorplate 2a) and of the later Codex Borgia Tlalocs (colorplate 1). But the figure could hardly appear less similar to those figures. Stylistically, it is Maya, strongly recalling the figures of Bonampak in its realistic features, graceful pose, and curvilinear style.[207] And its most striking symbolic feature, clearly related to fertility, has no counterpart at Teotihuacán; this is what seems to be a flowering vine springing from the abdomen of the figure rendered in a style reminiscent of the interlocking scrollwork characteristic of El Tajin. Whether this standing figure with all its fertility symbolism is meant to represent Tlaloc or to connect the representation of a ruler with the legitimizing symbols of that god as Pasztory and Donald McVicker argue,[208] the fact re-

Pl. 22.

"Tlaloc," mural painting, Cacaxtla. mains that the Teotihuacán Tlaloc depicted

on the typical urn continues its symbolic existence at Cacaxtla.

mains that the Teotihuacán Tlaloc depicted on the typical urn continues its symbolic existence at Cacaxtla

The case for the continuity of Tlaloc at Cholula is different since no major painting or sculpture depicting the god has yet been discovered there. It is generally felt, however, that the distinctive art style of the Postclassic period known as the Mixteca-Puebla either originated at or developed in conjunction with Cholula,[209] and most of the art of Postclassic central Mexico falls within what H. B. Nicholson, in discussing Aztec sculpture, calls "a broadly conceived Mixteca-Puebla stylistic universe,"[210] a style particularly associated with the art in which the Postclassic Mixtecs recorded their spiritual thought. In terms of our concern with Tlaloc, it is significant that although the Mixtecs were primarily located in Oaxaca, their rain god was not the Cocijo of the Zapotecs but was called "Zaaguy or Zavui (literally, 'rain')"[211] and depicted in images identical to Tlaloc. Although Mixtec scholars insist that there are significant differences between Mixtec spiritual thought and that of the Valley of Mexico,[212] the images through which that thought is expressed are virtually the same as are at least some of the meanings.

In the light of the connection between Tlaloc and rulership, Mary Elizabeth Smith's comments on the Mixtec codex known as the Vienna obverse are significant:

The deity motif that occurs most frequently in the names of persons who are historical and neither priests nor mythological personages is the rain deity known in Nahuatl as Tlaloc and in Mixtec as Dzavui. This deity is part of the names of 56 different rulers in the Mixtec genealogies. The prevalence of the rain deity motif in Mixtec names is not surprising because the Mixtec people call themselves in their own language ñuu dzavui, or "the people of the rain deity. "[213]

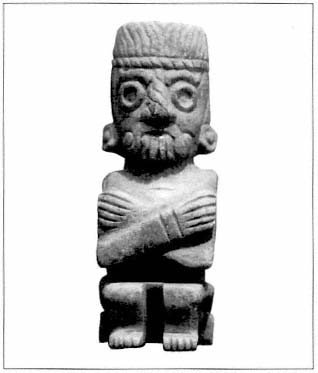

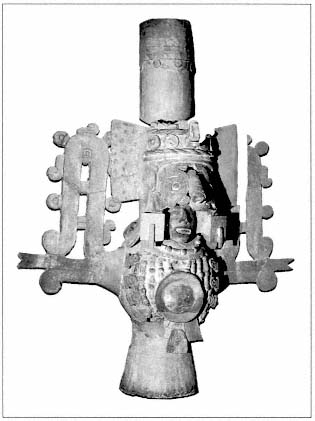

Her comment makes clear the reason for the abundance of similar images of the rain god in Mixtec art-in the other codices, on small greenstone figurines known as peñates (pl. 23), and on ceramic incense burners and xantiles.[214] In fact, the rain god is so fundamental to the art of the Mixtecs that Covarrubias sees the motif of the mouth and goggle eye in profile as a basic ideographic and decorative element.[215] Although "the most challenging problem connected with Mixteca-Puebla is still that of the precise time and place of its emergence as a clearly recognizable stylistic-iconographic tradition,"[216] it seems likely that Cholula was directly involved and was responsible for the movement of Teotihuacán's Tlaloc to Oaxaca under the name of Zavui.

Important as Xochicalco, Cacaxtla, and Cholula are to the later development of Tlaloc, the artists

Pl. 23.

Tlaloc, Mixtec peñate

(Museo Nacional de Antropologia, México).

and thinkers most directly responsible for the transmission of the Teotihuacán Tlaloc to the Aztec culture that dominated the Valley of Mexico at the time of the Conquest were the Toltecs of Tula. The chain of events that led to their assumption of the mantle of Teotihuacán in the Valley of Mexico is not clearly understood but probably involves the migration to Tula of groups carrying the culture of Teotihuacán.

They are referred to as wisemen, leaders, priests, merchants, and craftsmen; in other words, bearers of the Mesoamerican elite tradition. The sources indicate that they spoke Náhuatl, Popolaca, Mixtec, Mazatec, and Maya. This linguistic diversity suggests that they were not a single ethnic group but rather "civilized people" who migrated to Tula . . . when their home communities declined in power and importance.. . . . The prosperity they helped to create attracted more migrants and Tula soon became the New Teotihuacán .[217]

And as Diehl's summary of developments suggests, the symbolism of this New Teotihuacán was the one associated with the original Teotihuacán. While much has been made of the dominant symbolic role at Tula of Quetzalcóatl,[218] scant attention has been paid to the numerous images of the mask of Tlaloc there. This is strange since Tlaloc was of major importance at Teotihuacán, the source of the Toltec heritage, and, as Pasztory points out, "the god most frequently represented in Aztec art,"[219] the ultimate beneficiary of that heritage. And as we would expect, the evidence of Toltec art shows that the mask of Tlaloc was important at Tula. The recent excavations at that site directed by Diehl, for example, unearthed a small temple whose associated artifacts indicate that it was "devoted to the Tlaloc cult." Located near a large temple mound in the residential Canal Locality, the small Tlaloc temple would seem to have little relevance to Tlaloc's fertility associations, but Diehl suggests that the residential area may have been inhabited by priests who served the large temple and that the smaller Tlaloc temple may have been "a personal shrine for worship of their own tutelary god."[220] If so, Tlaloc survived at Tula in a privileged position and continued to demonstrate the connections with the priesthood he had at Teotihuacán due to his role in the provision of the order necessary for the maintenance of civilized life.

This supposition might suggest a reexamination of one of the better-known symbolic artworks at Tula. The frieze on the pyramid called the Temple of Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli, the aspect of Quetzalcóatl related to Venus as morning star, contains among other relief carvings a number of depictions of a face emerging from the open jaws of what appears to be a jaguar with a plumed headdress, the teeth of Tlaloc, and a bifurcated tongue (pl. 24). The emerging face consists only of goggle eyes, circular ear flares, and a large nose from which hangs a decorative pendant covering the mouth. The eyes and ears are those of the Teotihuacán Tlaloc, and the pendant is identical to those commonly seen in the art of Teotihuacán, especially on braziers, which are generally identified as butterflies. If this mask were found at Teotihuacán, it would be identified immediately as Tlaloc wearing a butterfly nose pendant. Strangely, however, at Tula it is seen as "Quetzalcóatl in the guise of Venus the Morning Star"[221] or, even more strangely, as "Quetzalcóatl in the guise of Tlaloc emerging from the jaws of a plumed serpent."[222] One suspects that such identifications are the result of the importance Quetzalcóatl is presumed to have had at Tula rather than an examination of the details of the relief. A similar Tlaloc can be seen in the headdress of a warrior depicted on a stela now in the Tula museum, and this one is surely Tlaloc since he wears no pendant covering his mouth, the mouth of Tlaloc. And should there be any doubt about the importance of Tlaloc, the numerous effigy urns, braziers, and figurines bearing his mask at Tula, the New Teotihuacán, would surely lay that doubt to rest.

Thus, even a brief consideration of the images of the mask of Tlaloc created outside of Teotihuacán during the decline and after the fall of that great city demonstrates that that god continued to be of fundamental symbolic importance in the area. In speaking of the relative importance at this time of Tlaloc vis-à-vis Quetzalcóatl, Davies says,

one should not exaggerate the degree to which Tlaloc suffered a decline. He still figures quite prominently in Xochicalco and even in Chichén Itzá; moreover it is Tlaloc rather than Quetzalcóatl who prevails in the designs of Plumbate pottery, the great trade ware of the Early Postclassic era.[223]

This type of pottery is generally associated with elites and ritual. The manifestations of Tlaloc in the lengthy period between the decline and fall of Teotihuacán and the rise to preeminence in the Valley of Mexico of Aztec Tenochtitlán are often associated with the art of the ruling class as well as with that of the farmers whose crops depended on the fertility associated with Tlaloc. The simple figurines, urns, and braziers were no doubt used in fertility ritual, but the stela at Xochicalco, the mural at Cacaxtla, the relief at Tula, and the plumbate pottery throughout the region served a different function. And that function of the mask of Tlaloc continued with even greater importance at Tenochtitlán, for in the Aztec capital Tlaloc shared the temple atop the Templo Mayor, the central temple of the ceremonial center of the city, with Huitzilopochtli, the tutelary god of the Aztecs.

Although the documentary sources dating to the

Pl. 24

The face of Tlaloc emerging from a jaguar's mouth wearing a butterfly nose pendant, relief on Pyramid B, Tula.

time of the Conquest stress the importance of Huitzilopochtli, the recent excavations at the Templo Mayor tell a different story.

A quick review of the materials found in the Templo Mayor offerings forces us to see the importance of the god Tlaloc, present in stone masks, stone figurines, and pottery . . . [and symbolically alluded to by] a great quantity and variety of biological remains such as snails, shells, coral, fish, birds, turtles coming from both coasts. Moreover, there are symbols associated with the god, such as the presence of canoes and stone serpents. One can affirm without doubt that the vast majority of the material found was associated with Tlaloc .[224]

The essential reason for the importance of Tlaloc at the Templo Mayor, which was for the Aztecs "the fundamental center where all sacred power is concentrated,"[225] was the attempt by the Aztec ruling elite to identify themselves with and carry forward in time the sacralized political tradition of the Valley of Mexico which had its origin at Teotihuacán and a subsequent period of development among the Toltecs at Tula. For the Aztecs,

the "Toltec" past was crystallized around the figure of the god Tlaloc who shared the twin pyramid with Huitzilopochtli. . . . A striking aspect of the Aztec attitude to Tlaloc, as revealed by the Templo Mayor excavations, is how much of the offerings buried in the temple were dedicated to Tlaloc and how many representations of him exist in stone and clay. Tlaloc, as deity of the earth, also occurs on the underside of important sculptures, such as the Coatlicue, where he was not visible to anyone. The concern with the power of Tlaloc was therefore not merely a theatrical display for the sake of politics but also a demonstration of what the elite believed to be a historical and religious truth. Tlaloc was the personification of the past in the present.

While the Temple of Huitzilopochtli atop the Templo Mayor suggests that the Aztecs thought of themselves as "the descendants of nomads led by Huitzilopochtli," Tlaloc's temple reveals an opposed self-image that was equally true: "we are the legitimate successors of the Toltecs and their god Tlaloc."[226] And while the Aztecs as the nomadic followers of Huitzilopochtli formed a warrior state that maintained its power through the sacrifice of countless victims on the sacrificial stone still in place in the Temple of Huitzilopochtli, those same Aztecs, as the "successors of the Toltecs," were more inclined to philosophical speculation and artistic expression. Sahagún reveals the Aztec view of that heritage:

These Toltecs were very religious men, great lovers of the truth,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

These Toltecs were very wise;

it was their custom to converse with their own hearts.

They began the year count,

the counting of days and destinies.

In the Aztec expression of those truths of the heart, "the true artist . . . works like a Toltec." He "draws out all from his heart" and "works with delight; makes things with calm, with sagacity."[227] Thus, the Aztecs saw themselves as the carriers of the tradition that began at Teotihuacán and that they identified as Toltec. H. B. Nicholson describes their system of philosophical speculation and artistic expression precisely in that way as

a final precipitate of the ceaseless flow of iconographic development and change stretching over a period of more than two millennia from the Early Preclassic to the Conquest. No system, therefore, probably better epitomizes the whole intricate fabric of Mesoamerican symbolism, the tangible graphic expression of the religious ideologies that played such a pervasive role in Mesoamerican civilization .[228]

It therefore follows that the meanings associated with the mask of Tlaloc in that system are the result of the centuries-long development of that symbolic mask which we have traced in this study. And in that sense at least, the mask of Tlaloc symbolizes the system as a whole.

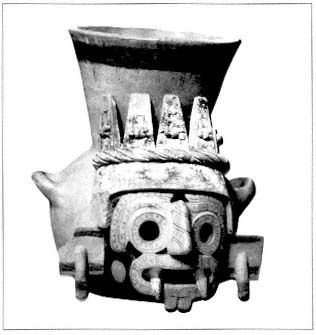

Significantly, among "the most spectacular" of the ceramic finds at the Templo Mayor, "a center dedicated to the major gods of the Aztec state cult, " is a pair of almost identical Tlaloc effigy urns (pl. 25) similar in design to those carried by the Tlalocs of the Teotihuacán and Cacaxtla murals and to those found in burials and offerings from the Preclassic period on. These two were found separately in Offerings 21 and 56, but each contained three oyster shells,[229] aquatic symbols related to Tlaloc. An iconographically similar ceramic urn was found in Offering 31,[230] and a sculpted stone version was found in Offering 17.[231] These urns surely indicate the persistence of the view that the rain, Tlaloc's water, was stored in great urns that were thus the source of fertility, and the symbols composing the masks on them suggest their roots in the preceding cultures.

Pl. 25.

Tlaloc urn, Templo Mayor, Tenochtitlàn.

(Museo del Templo Mayor, Mèxico).

The goggle eyes of the masks on the urns are those of the Teotihuacàn Tlaloc; however, in all four of the masks, those eyes are surmounted by eyebrows that entwine to form the nose, a familiar motif in Aztec images of Tlaloc which, as a number of those images makes clear, represents serpents. According to Seler, a sculpture now in Berlin has a face "made up of the twinings of two serpents," and he concluded that Tlaloc's typical goggle eyes and upper lip were derived from that original conception.[232] But as we have seen, those features were already part of the earliest Tlaloc images, long before entwined serpents made their appearance on the mask. Furthermore, as these urns demonstrate, the serpents form the eyebrows and nose; the goggle eyes remain under those eyebrows. It seems likely that the Aztecs devised this eyebrow/nose configuration as another means of suggesting the serpent symbolism manifested in the bifurcated tongue associated with Tlaloc from the earliest times. And like the eyebrows, the ear flares on these masks also differ from those found on the Teotihuacán Tlaloc; they are a rectangular variant of those circular ones and have pendants similar to the pendants on the mask on Xochicalco Stela 2 (pl. 21) hanging from their centers. But the all-important symbolic mouths are those of Teotihuacán. The masks on the three ceramic urns have their upper and lower lips joined to form an oval mouth from which two outer fangs, with no teeth between them, protrude; below the mouth is the suggestion of a bifurcated tongue. The mask on the stone urn, in contrast, displays the more typical Tlaloc handlebar mustache upper lip from beneath which protrude four curving fangs; this mask has no tongue.[233] Thus, the two mouth treatments found at Teotihuacán continue to occur at Tenochtitlán.

The more common of the two, by far, is the "handlebar mustache" type. It is generally found on the numerous stone figurines of the god carved by the Aztecs and is the mouth seen on the god in the codices, where the mask is almost always depicted in profile. As it is quite similar to the mask

depicted on the Mixtec peñates (pl. 23) and as it is found in the codices of Mixtec origin, it may have traveled from Teotihuacán to the Mixtecs and from that culture to the Aztecs.[234] These urns, then, display masks that have features associated with all of the cultures and art styles derived from Teotihuacán. The Aztecs, in achieving a Teotihuacán-like hegemony over the peoples of the Valley of Mexico and related areas, seem also to have reunited, symbolically, the features of the mask of Tlaloc.

And the reverse is also true. The Tlaloc whose images we find at Tenochtitlán can be found throughout the Valley of Mexico and in politically related areas such as Veracruz, Puebla, Oaxaca, and Guerrero during the Aztec period. In Veracruz, for example, where Tlaloc images are practically nonexistent in the Classic period, stone and ceramic figures with the mask of the Aztec Tlaloc have been found at a number of Postclassic sites. Castillo de Teayo provides an apt example since a number of stone sculptures bearing Tlaloc masks have been found there. One of them, a relief carving of the god on a tall, narrow slab, has a mask virtually identical to that found on the stone urn of the Templo Mayor. The figure wears a headdress displaying the year sign, indicating the continuity of that aspect of the Teotihuacán Tlaloc as well. But fertility continues to be Tlaloc's primary symbolic concern, as another relief carving from the same site (pl. 26) indicates. It depicts, very much in the style of the codices, Tlaloc holding a cornstalk and facing another fertility-related figure. These representations of the mask of the god all display the handlebar mustache mouth, but a large, striking ceramic incensario from central Veracruz now in the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City illustrates the existence in Veracruz of the oval-mouthed Tlaloc mask as well.

And in Puebla and Oaxaca, the Mixtec images of Tlaloc originating in the late Classic period continued to be produced during the time of the Aztecs. The iconography of those images finds its most complex statement in the pre-Conquest codices in the Mixteca-Puebla style probably associated with that area, and it is in one of these codices, in fact, that Pasztory finds the central image of the Postclassic Tlaloc. The images of the god in his characteristic mask on page 27 of the Codex Borgia (colorplate 1) make clear his great significance in the philosophical speculation involved with calendrical studies by the priesthood. Seler describes and then analyzes these images.

We see, one in each of the four corners of the picture, four images of Tlaloc which designate the four cardinal points. The fifth image in the

Pl. 26.

Tlaloc holding a corn stalk and facing another fertility related figure, relief carving, Castillo de Teayo, Veracruz

(Museo de Antropologia de Xalapa).

center naturally corresponds to the fifth region of the world, the center or the vertical axis... It is likely that images of Tlaloc were chosen to represent the cardinal points because the god of rain rules over all. Because of this relationship between the god of rain and the four cardinal points, the Zapotec calendar designates the initial days of the four quarters of the tonalámatl by the names of Cocijo, god of rain, or pitao, "the great" or "the god." We may surmise that it was extremely important in the picture we are discussing to connect man's well-being to the significance of the four periods and the years characterized by the four distinct signs corresponding to the cardinal points.

But a further suggestion of Seler's indicates just how important these images in particular were.

To the ancient seers it must have seemed marvelous that of the twenty day-signs, only four fell on the initial days of the years, but we can imagine that they considered as a veritable mystery the division of the 52 year cycle ... into four quarters, each of which had as its initial day a day numbered 1 which had one of those same four day-signs in the proper sequence. Thus the 52 year cycle was automatically ordered in accord with the four cardinal points in the same way that the tonalámatl . . . organized itself into four sections similarly corresponding to the four directions. And this division of the 52 year cycle in accord with the four cardinal points is what is represented on page 27 of our manuscript.[235]

On this page is recorded, then, the central mystery of the division of the essential unity of the cosmos into the quadripartite form of the world of man. The images here reproduce what we will describe below as the essential "shape" of the space-time continuum as perceived by the sages of Mesoamerica. The significance of Tlaloc serving as the vehicle for the expression of this mystery is enormous, but another aspect of the page suggests that his image is even more significant. While the four images of Tlaloc representing the cardinal points, that is, the world of nature, each wears a mask helmet representing another symbolic identity, the Tlaloc of the center who represents the all-important vertical axis of the spirit wears no such mask. He is the essential Tlaloc, the "thing itself," as close as man can come to depicting the essential reality of the world of the spirit.

And these images of Tlaloc are virtually identical to those of Tenochtitlán, as are those from Veracruz, so it seems reasonable to conclude that the Tlaloc mask we find of such importance at Tenochtitlán's Templo Mayor was of equal importance throughout the area influenced by the power that ruled there. What H. B. Nicholson says generally of that Aztec influence applies remarkably well to the mask of Tlaloc. The Aztecs, he says, "clearly shared the majority of their fundamental ideological and socio-political patterns with most of their neighbors, both those subject to their greater military power and those who had successfully withstood it."[236]

That the masks depicted on the urns of the Templo Mayor and reproduced so widely actually were conceived as masks is made clear by the form of their appearance on another type of ceramic sculpture—the large ceremonial incensarios that "stood at the top of the balustrades of pyramid stairways"[237] to house the burning copal which symbolized the transformation of matter to spirit and created the clouds of smoke that would call forth the rain clouds, which would in turn transform spirit into the nourishing reality of corn. Several of these large incensarios display a human figure wearing a Tlaloc mask in such a way that the man's face is clearly visible beneath the mask (pl. 27), a form of great symbolic importance in Mesoamerican art which will be discussed in our consideration of the ritual use of the mask. In the case of these incensarios, the visibility of both face and mask would suggest the same matter-spirit dichotomy as the fire that burned within the image of the man-god.

These incensarios symbolically link fire and water in their concern with the provision of man's sustenance, a linkage we saw earlier at Teotihuacán in the Tlalocan mural (colorplate 3). That this is not a coincidental connection is suggested by the discovery of another figure at the Templo Mayor which makes that same connection in the context of a clear reference to the art of Teotihuacán. It is a sculpture that "copies stone braziers from the Classic Teotihuacán period . . in the form of an old god carrying a vessel on its head,"[238] but in this case, the Aztec sculptor partially covers the old god's face with the goggles and buccal mask of Tlaloc to create precisely the same symbolic linkage of fire and water differently symbolized by the mask of the central figure of the Tlalocan mural at Teotihuacán. This reference to Teotihuacán is reinforced by the reference of the form; this image of the old god of fire, Huehuetéotl, is unusual in Aztec art but was quite common at Teotihuacán (pl. 19). After creating this archaic form in what must have been a conscious allusion, the sculptor made clear with the addition of the mask of Tlaloc in a peculiarly Aztec version that his intention was not to copy the past but to interpret it for his own time. The goggles and the mouth of this mask are rectangular rather than circular and oval, and the other details of the sculpture complement these "Aztec" touches, touches that can also be seen on an Aztec Chac Mool, which similarly copies a Toltec form. While the sides of the brazier carry the diamond eye and bar design found at Teotihuacán and used in the Tlalocan mural to symbolize fire, the top is

Pl. 27.

Ritual figure wearing a mask of Tlaloc, Aztec incensario,

Azcapotzalco (Museo Nacional de Antropologia, Mexico).

sealed and decorated with "snails, whirlpools, and water motifs," thereby uniting fire with water by placing aquatic symbols precisely where the mind expects fire. And the elbows and knees of the figure are uncharacteristically decorated with Tlaloc-like masks of the "handlebar mustache" variety.[239] This figure, like the Tlalocan mural figure, is a virtual hymn to creativity in its linkage of an aspect of the creator god to the god who assures the creativity of the earth and in its uniting of the fire that "spiritualizes" matter with the water that "materializes" spirit. If this figure originally found its place in a temple dedicated to Tlaloc, as seems likely, it would have stressed the breadth of the symbolic range of that god in the thought of Aztec Tenochtitlán.[240]

The recently uncovered second temple of the Templo Mayor also provides us with another "mask" of Tlaloc, this one in the most abstract possible form but also reminiscent of Teotihuacán. Behind the Chac Mool on the narrow walls flanking the entrance to the interior of the small temple are mural paintings of a seemingly abstract design (colorplate 5a). Although there are traces of blue paint above suggesting a portion of the mural now lost, what remains is a band of white concentric circles set on a black ground immediately above a blue band containing black circles, both of which are above a solid red band. These horizontal bands surmount a row of alternating black and white vertical stripes. The location of this painting suggests that the Aztec artist has "deconstructed" the Tlaloc mask and then constructed an abstract representation of its symbolic elements—Tlaloc's goggle eyes and fangs—to flank the "mouth" of the temple of the god. Interestingly, a similar composition of these elements is to be found in a mural on Teotihuacán's sacred Avenue of the Dead (colorplate 5b) painted almost a millennium earlier. In that earlier version, the vertical lines are wavy, probably suggesting water in this city overwhelmingly concerned with Tlaloc, and superimposed on the mural is the figure of a jaguar, the creature associated with the god of rain from the beginning of Mesoamerican thought.

The serpent symbolism evident in the mask of Tlaloc has led to the suggestion that "the Aztec Tlaloc is no longer feline; fundamentally his nahual is the serpent. The jaguar of the hot lowlands does not represent Tlaloc in the highlands,"[241] so that by the time of the Aztecs, the jaguar was fundamentally associated with the earth god and with Tezcatlipoca rather than with Tlaloc. While it is certainly true that the jaguar was of great symbolic importance and that its symbolism did encompass the caves of the earth god and the mysterious darkness of the night associated with Tezcatlipoca, it is equally true that the jaguar maintains its fundamental relationship to Tlaloc at Tenochtitlán. Although the eyes of the Aztec Tlaloc are symbolically associated with the serpent, the mouth and fangs of Tlaloc are those of the jaguar, as we have demonstrated in our discussion of the Teotihuacán Tlaloc. And the recent excavations at the Templo Mayor have added further evidence of the symbolic relationship between the jaguar and Tlaloc, for "among the offerings are numerous jaguar skulls, some of which carry egg-sized jade stones (a symbol of life and regeneration) in their mouths; even a complete skeleton of a jaguar was found placed on top of other offerings dedicated to Tlaloc."[242] The remains of that jaguar testify to the direct line of continuity linking the Olmec were-jaguar mask to the Aztec Tlaloc presiding over the imperial state conquered by Cortés.