Position, Strategy, and Execution

Bent & St. Vrain Company owed its considerable success to the ability of the principals to understand, and to skillfully operate within, the emerging capitalistic world market and the Native American trading systems. The fort was essential to the company's strategy.

Whereas other entrepreneurs had deployed their own trappers or had attended Native American trading rendezvous, Bent and St. Vrain saw that operating from fixed trading posts would be a superior strategy in the trading environment of the southwestern Plains in the early 1830s. Buffalo hides were supplanting beaver pelts as the most desirable of furs in the trade. These could be procured solely from the Plains Indians, who

knew not only how to hunt the buffalo but also how to prepare the fur. Various tribes among the Plains Indians, though, militantly protected the positions they had established as middlemen in Native American trade. The fixed trading posts let some of the tribes enhance their position.

Pacifying Native American groups by allowing them an important role in the fur trade permitted Bent & St. Vrain Company to maintain a presence on the international border. New Mexico, with its untrapped rivers and untapped reserves of Mexican silver, horses, mules, and blankets, lay just across the Arkansas River from the fort. The large adobe fort offered an alternate trading locale to the ancient fairs held at Taos and Pecos pueblos and the more recent Spanish and Mexican trade at the cities of Taos and Santa Fe. From the day business began at the fort, the availability of manufactured goods there drew trade from the New Mexican pueblos and cities.

During the height of the favorable market configuration, Bent & St. Vrain Company operated several smaller trading posts on the southwestern Plains in order to maximize their profits (see fig. 9). Intertribal fighting made these posts desirable, since warring Native American groups were cautious about entering territories frequented by their enemies. In 1842, Bent & St. Vrain Company built a log trading post on the south fork of the Canadian River, in what is now the panhandle of Texas. In 1845, they built a more permanent adobe post a few miles from the first. The second post on the Canadian became known as "Adobe Walls" (and was the scene of two famous battles between Anglos and Native Americans after its abandonment). These posts were established to facilitate trade with the Kiowa and Comanche, who were generally loath to venture north of the Arkansas River into the territory, of the Cheyenne and Arapaho, despite the Bent & St. Vrain Company's continuing efforts to make a peace between these tribes.

Earlier, Bent & St. Vrain Company had built a substantial adobe trading post on the South Platte, north of the future site of Denver and twelve miles below what would be called St. Vrain Creek. George Bent, the brother who probably supervised its construction, named it Fort Lookout. Later it would be known as Fort George, and finally as Fort St. Vrain, most likely because by that time Ceran St. Vrain's brother Marcellin was frequently in charge there. Fort St. Vrain was more accessible to some of the bands of Cheyenne and Arapaho who preferred to stay north of the South Platte and to the Ute, Sioux, and Shoshoni. The establishment of the fort, moreover, neutralized attempts by several other traders to establish posts in that vicinity.

Figure 9.

The trading empire of Bent & St. Vrain Company. (Illustration by Steven Patricia.)

Probably for the reason of eliminating competition, Fort Jackson, also on the South Platte, was purchased in 1838 from the firm of Sarpy and Fraeb. The fort had been backed by the powerful American Fur Company. An agreement was reached just after the negotiations for the fort were concluded: thenceforth, Bent & St. Vrain Company would not send trading parties north of the North Platte River, while the American Fur Company would no longer encroach upon the territory south of there.[9] Of the "cartel" thus formed, David Lavender commented, "And so in 1838 big business sliced up the western half of America.[10] There is every reason to think that Ceran St. Vrain negotiated this agreement by means of his close personal relationship with the family of Bernard Pratte, who was the head of the company that served as the American Fur Company's western office.

Bent's Old Fort was the most remarkable structure in the West until the mid nineteenth century and the most dominant feature in the history of the southwestern Plains. As David Lavender has pointed out: "In nearly two thousand miles from the Mississippi to the Pacific there was no other building that approached it. Only the American Fur Company's Fort Pierre and Fort Union up the Missouri were comparable."[11] Matt Field, a correspondent for the New Orleans Picayune who visited the fort in 1839 wrote that it was, "as though an air-built castle had dropped to earth. . . in the midst of the vast desert."[12] Did the Bents intend to impress and influence those with whom they dealt by the sheer size of the fort and its architecture, which evoked thoughts of grand castles? We cannot say with certainty, but we do know that the structure itself awed many who visited there. We know also that this worked on numerous occasions to the advantage of Bent & St. Vrain Company. By this and other means, the principals of Bent & St. Vrain were uncommonly adept at influencing persons from many different cultures and backgrounds to act for the benefit of the company. For a quarter-century they exercised control of the region from their fort.

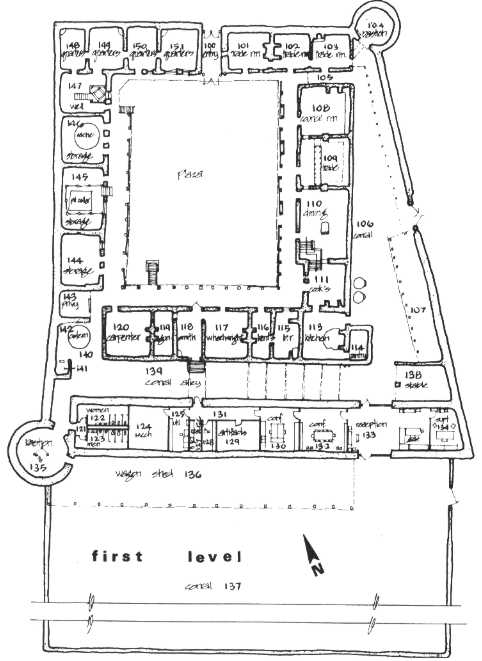

The best presentation of the dimensions of the fort, drawn from at least twenty-six firsthand written observations and three archaeological excavations at the site, was provided by George Thorson, the National Park Service architect in charge of the reconstruction of the fort (see fig. 10). Synthesizing from the various sources, he concluded:

The fort was divided into four main areas: the compound, the inner corral, the wagon room, and the main corral. The compound was essentially a rectangular core of buildings (115 feet by 135 feet) around an inner plaza (80 feet

by 90 feet). The inner corral on the east was a wedge-shaped area about 10 feet wide at the northeast bastion, expanding to 40 feet wide at the south. A 15-foot alley separated the compound from the 20-foot wagon house on the south and the 27-foot diameter bastion on the southwest corner. Therefore, the main fort was about 130 feet on the north front and 180 feet on the south with a 175-foot depth. Behind to the south was the main corral at 150 feet by approximately 14O feet (the precise dimension was lost due to earth disturbance). Twenty-nine rooms were identified on the lower level and 9 on the upper level. The enclosed rooms encompassed almost 17,000 square feet. The overall fort proper covered over 27,000 square feet, and the outer corral covered 21,000 square feet for a total of over 48,000 square feet, well over 1 acre.[13]

The fort was built without benefit of architectural drawings, and there was a lack of uniformity, evident in numerous aspects of the fort's construction. The thickness of the exterior walls varied from about 2 to 2.5 feet. A National Park Service employee who was on site for several years before reconstruction began has said that the foundations of the fort, previously visible at ground surface, were not straight, but meandered along a generally linear path.[14] Modifications and additions were made throughout the fort at various times during its use, and some discrepancies between documented and observed dimensions may be due to modifications that were made after documentation. Some of the most extensive of these were made during the years 1840-41 and 1846, as activities that culminated in the Mexican War intensified.

Archaeological evidence has indicated that the two most distinctive features of the fort, the towers or "bastions" at the northeast and southwest comers of the fort proper (excluding the main corral) were of different diameters. Although Lieutenant Abert, a skilled illustrator who visited the fort in 1845 with the U.S. Army, recorded the diameter of both bastions as 27 feet, archaeological examination of the remains did not verify this. The southwest bastion is 27 feet in diameter, but the northeast is only about 20 feet.

During the fort's occupation, eight visitors recorded estimates of wall height, and these ranged from 15 to 30 feet, the average estimate being about 19 feet.[15] Only one visitor, John Robert Forsyth, estimated the height of the bastions. Forsyth, who stopped at the fort for a few days in 1849 on his way to California to search for gold, recorded in his journal that the bastions were 25 feet high.[16] The attached main corral walls were not as imposing as the walls of the fort proper, but they could be defended by arms fired from the fort in an attack. The walls here were probably 6 to 8 feet high and, by some accounts, were planted on top with thick

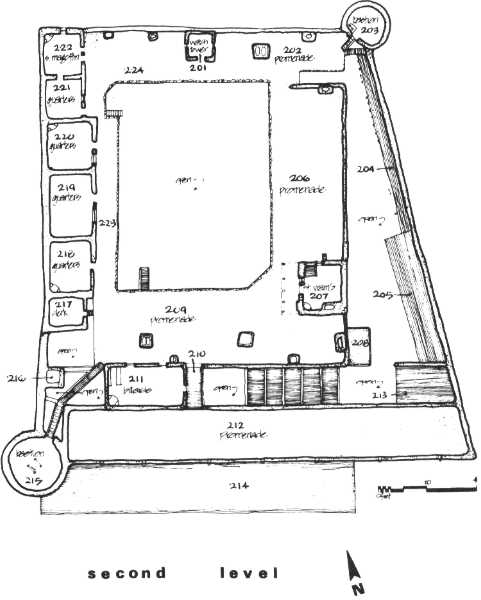

Figure 10.

Plan view of the two levels of Bent's Old Fort. (Courtesy Colorado

Historical Society, Denver; from George A. Thorson, "The

Architectural Challenge," Colorado Magazine [Fall 1977]: 112-113.)

Figure 11.

Aerial view of the excavated foundation of Bent's Old Fort,

taken in 1964. (Courtesy Colorado Historical Society, Denver.)

cactus—a reasonable precaution in a country where horse stealing was an honored occupation.

From overhead, the entire structure would have appeared trapezoidal (fig. 11). The two corners thus produced, one obtuse and the other acute, afforded less cover to a person approaching from the back of the fort than would have two corners of 90 degrees. Without this aspect of the fort's design the corral area would have been less open to surveillance from the bastions and second floor of the fort.

It is plain that the fort was constructed to withstand any attack the Plains Indians might mount, and perhaps an attack from the Mexican army as well. Entry to the fort was restricted to a sort of a tunnel, a zaguan, in the front. The door to the zaguan was of stout wooden planks, sheathed with iron. Above was a watchtower with windows on three sides and a door on the fourth, providing views in all directions. A telescope assisted the watchman on duty. In the sides of the zaguan were small windows, which could be firmly closed or opened, so that goods could be passed to those Indians who were denied full admission to the fort. A brass cannon, mounted atop the northeast bastion, was fired on special occasions with an impressive report. Both bastions were filled with arms. Grinnell claimed:

Around the walls in the second stories of the bastions hung sabers, and great heavy lances with long sharp blades . . . for use in case an attempt should be made to take the fort by means of ladders up against the walls. Besides these cutting and piercing instruments the walls were hung with flintlock muskets and pistols.[17]

A large American flag flew from a pole adjacent to the west side of the watchtower, proclaiming the presence and power of a young country marching westward.

On the inside, the design of the fort showed the influence of both Pueblo and Spanish architecture. Room blocks formed the perimeter of the fort, about twenty-nine rooms on the ground floor, perhaps 15 by 20 feet in size. The tops of these room blocks were fiat, and a man could take cover behind the parapet that was formed by the fort's exterior wall as it extended above the roof of these rooms. More rooms were added to form a full second story along the west side of the fort; rooms were also built atop the southeast comer. Huge vigas, cottonwood trunks, formed the superstructure of the fort and were visible in the ceilings of the rooms. Almost every room had a fireplace for warmth in the winter and on chilly evenings. During the heat of the summer, the thick adobe walls provided cool shelter.

Some rooms were for sleeping, but more were for other uses. On the first floor were storage rooms, the trading rooms, the kitchen and dining hall, and workshops for tailoring, carpentry, and blacksmithing (where activity was as incessant as in the kitchen). An office for clerks was located on the second floor. Also on the second floor was a special, large room where the fort's owners entertained friends and visitors; eventually this room contained a billiard table and bar. Usually the elite of the fort's rigid social hierarchy lived and socialized on the second floor. It appears that the Bents and St. Vrain may have had rooms on both floors, and may have had access to both by means of stairways located within or just outside their quarters.[18]

When completed, the fort could house about two hundred men and three to four hundred animals. It was staffed by almost every. race and nationality that had come to the West. In addition to accommodations for those that slept within the fort's walls, many Indian lodges were frequently set up near the fort, and the numbers of Cheyenne and Arapaho who occupied them added to the activity at the fort during the day.

Bent's Old Fort dominated trade in the Southwest for almost two decades. This trade yielded immense profits in furs and silver, profits that

American businessmen had sought for decades. At the beginning of this period, the fort was a unique American presence; at the end, the area it occupied became a part of the United States.

Many of those closely associated with the fort are well known to historians, and some are familiar to almost all Americans. Perhaps the best known of those who had close ties to the fort is Kit Carson. Popularly known also are Thomas Fitzpatrick, Bill Sublette, "Uncle Dick" Wootton, "Peg-leg" Smith, and other trappers and traders. Virtually every American active in the Southwest who had any influence in commercial or political events in the second quarter of the nineteenth century visited the fort. This included all of the traders and trappers in the region. The fort was used as a staging area by General Kearny's Army of the West just prior to its invasion of Mexico at the outbreak of war in 1846, and the fort had effectively operated as a center for the collection of intelligence for that war for many years before the invasion.

Bent's Old Fort provided rich financial rewards to those associated with it. By 1840, the trading profits of Bent & St. Vrain Company were second only to those of the American Fur Company.