PART III—

UNDER THE RAISED TRELLISES

Negative Architecture

For anyone who lingers about ruins, there's invariably some structure—some solid, wind-pitted rampart, for instance—to admire, meditate upon. Here, though, in the Greco-Massalian quarries along the French littoral, no particular feature draws our attention if not the squares and rectangles of extracted volume, if not the hewn outlines, in fact, of a distinct counterstructure. For we've entered, architectonically speaking, a world in negative. We've wandered into a space that we can only read—and in reading, interpret—by attending to the eloquence of its voids. At La Pointe de l'Arquet in the commune of La Couronne, we might find ourselves staring at a jagged set of right angles carved out of some low limestone ledge. Isn't the right angle the very signature, the trace par excellence of human passage? Here, however, the sign doesn't indicate some small, incremental step in a given construction. To the contrary, it signifies depletion. Designates the geometric outlines of excavated mass.

We stand there, gazing down. Stand at the edge of this narrow, wind-blown

Greek quarries at La Pointe de I' Arquet.

Photo by the author.

peninsula, gazing at the tide as it invades the lowest levels of the quarry itself. It covers, in a thin, limpid sheath, the broad checkerboard pattern created over two thousand years earlier out of all those extracted sections. If anything, the tide tends to magnify those sections, exaggerate the already immense emptiness of the abandoned worksite itself. It's not every day, we realize, that we're allowed to gaze into the contours of absence, into the specific proportions, dimensions, properties that absence, under a given set of conditions, has assumed. Is memory any different? Aren't we continually running over the imprint, the deeply scored outlines of vanished experience, attempting to read—in counterpoint—the plenitude of so many irrecuperable events, read-

ing here what's eternally there ? It's not altogether different with the quarries. They once supplied Marseilles (Ionian Massalia) with the materials for its ramparts, administrative buildings, theaters, and temples. Furnished it, out of all these successive limestone layers, with its long lost architectural splendors. In either case, we're left—as readers—confronting lacunae: interpreting, as we go, volume from depleted vestige.

The earliest surviving mention of the site comes from Strabo. In his invaluable (if often inaccurate) Geographica , he wrote: "A bit further than Massalia, at about one hundred stadia [eighteen kilometers] from the city and lying against a rocky promontory [certainly that of La Chaîne de l'Estaque] these quarries face directly onto the coastline, just before the coastline itself curves inward to form the Gulf Gaulois."[1] Why there? We, as would-be historians-interpreting history by all this hollow human imprint, by the fossilization of so much arduous human effort—learn that this particular limestone was ideally suited for construction. Relatively easy to extract, to carve into six coherent surfaces, the blocks were remarkable for their high compressive strength. Furthermore, they were exceedingly handsome. Encrusted with opalescent oyster shell, the stone itself—Tertiary, Miocene—gave off a pale, ocher-rose cast. We can only imagine, today, how the facades of a temple dedicated to the much venerated Artemis must have appeared. Can only imagine how its pediment, the color of dawn, must have glowed under a deep mistral blue. Imagine, we say, because we only have these cratered outlines, now, to serve as witness: only the jagged edges of all these successive limestone shelves.

The fact that the quarries themselves are located alongside the coastline isn't, of course, fortuitous. Scows could moor flush alongside them in waters three meters deep. Indeed, one can still see notches carved into the bedrock to receive the cables of those vessels as they came to berth. Called by the Romans

naves lapidariae , they could take up to three-and-a-half tons of cargo in their deep holds. If this seems like an inordinate amount for such times, we might consider the wreckage of the Marzamemi III , sunk off the eastern coast of Sicily, which held twenty tons of granite destined for the temples of Thebes. We are, after all, studying a moment in which cultures expressed themselves in monumental terms. We shouldn't be surprised by either the magnitude of their undertakings or the extent of geological spoliation they occasioned. If the Greek sense of scale was harmonious and based on human proportion, its sense of mass—at the same time—was colossal.

Standing here, on the tip of this narrow peninsula, we can stare clear across the open waters to Marseilles itself. It lies at a distance of twenty-five kilometers (rather than the eighteen specified by Strabo). It would have been a direct run for those naves , hugging—if need be—the littoral in times of heavy weather. In fact, as we stand here, gauging the distance between quarry and building site—La Pointe de l'Arquet and Marseilles—it's safe to speculate that virtually every stone block that went into the construction of the antique city was, at one moment or another, afloat, buoyed in the wooden hull of some stout, shuttling cargo. Each ponderous volume must have displaced its own weight in a draft of deep underlying seawater.

We're fortunate, today, to have documentation on those volumes: on their extraction, transportation, and ultimate deployment. Of the volumes themselves, however, scarcely anything remains, only an Ionic column here, a bit of truncated rampart there, vestiges discovered quite by accident in excavating the antique city—not for itself, but for the sake of preparing the ground for modern high-rise office buildings. Nevertheless, these materials have provided the specialist with enough data to conduct their examinations and arrive at certain conclusions. For instance, geomorphologists have managed to com-

pare in sophisticated laboratory analyses thin laminated strips of limestone taken from the antique blocks themselves with others, drawn from various areas in the quarry. They've managed to match one with the other: a specimen, say, from a shattered, bulldozed section of a once elegant entablature with that of a certain stratigraphic level at L'Arquet. They've been found to coincide with astonishing accuracy.

Other analyses, based on measure alone (metrological), have proved to be equally conclusive. Here, it's the dimensions of the blocks themselves that have undergone scrutiny. These incumbent masses have been measured against—compared with—their hollow counterparts in the quarries. The results of these analyses at first puzzled the specialists. For they discovered that the dimensions of the former (the blocks) didn't exactly match those of the latter (the hollows): that the masses were invariably a centimeter or two less than the hacked-out rectangles they'd created within the quarries themselves. It soon became evident that the blocks had been carved twice: first, by the quarrymen, the latamoi , at the quarry proper; then, after transport, by the stone carvers, the lapicides , working at the base of some rampart or along the plinth of some elegant oratory. There, each block, arriving rough-cast from the quarries, would be rasped, redressed, shaped to fit, with astonishing accuracy, its assigned place. This double preparation would account, of course, for the minute loss in the block's final dimensions: what has been measured, by the specialists, down to the last, seemingly inconsequential millimeter.

There's something touching, indeed, in all the care, the meticulous attention given, nowadays, to all this vestige. There's something disturbing, however, as well. We're far richer, today, in voids than in entities: in the mineral outlines of absence than the assembled masses that the absence once articulated. How, in fact, should we read this empty text, these low, outlying shelves

at the Mediterranean's edge that the tide, now, has totally invested? In negative? Like a negative held, say, against the light? If so, it's one from which we might readily glean (in default of any existent print) an incisive image. For we have, after all, the hacked, chiseled, quoined profile of an entire vanished city lying before us like a text of sorts, written in its own particular idiom. Written in what might be called an inverted grammar. We must read it, learn to read it, like memory itself. Follow it, this very moment, over its flooded rectangles—rife with tiny propellant cuttlefish—as if we'd just entered the empty chambers of some long suppressed recollection.

No, it's not in Marseilles, in the dusty showcases of its museums or the sparse architectural fragments to be found in its Jardin des Vestiges, but here, in interpreting these lacunae, that we'll come to approach such losses. Come to appreciate, perhaps, their very magnitude. Bit by bit, we might even come to read, in that inverted grammar, the otherwise lost text of the sea city itself. An idiom of its own, it deserves our utmost attention.

Undulant-Oblique:

A Study of Wave Patterns on Ionico-Massalian Pottery

If wine, as we're told, allowed Mediterranean civilization to penetrate the still-protohistoric world of Provence, the history of wine cannot be disassociated from the amphoras in which it was transported, nor the cups, kraters, skyphos from which it was drunk.[1] For here, "contained" and "container" form a single cultural entity. Imported into Provence in the seventh century B.C. by both Etruscans and Phoenicians, wine and, inseparably, the clay vessels in which it came constituted—as barter—the single most sought-after commodity. With the arrival of the Ionians a century later, this trade increased considerably. For the Ionians not only exchanged goods with the indigenous populations (trading essentially wine, pottery, and bronze ware for tin, iron, and salt) but established emporia of their own for stocking and distributing those goods. The first and by far the most significant of those emporia—those fortified trading posts—was Massalia: present-day Marseilles.

Called by Herodotus the "progenitors of history," the Ionians were Greeks

who had settled in Asia Minor and assimilated the cultures of kindred societies flourishing in those very regions. This assimilation would prove to be highly generative. Founding, in a short period of time, their own schools of philosophy, art, and architecture, inventing coinage, and propagating the acquisitions of an entirely original culture throughout the Mediterranean, they quickly became the radiant center of all Hellenism. Nothing they touched, it seems, wasn't marked by a natural sense of measure, grace, innate proportion, by what might be called, indeed, an "auroral intelligence."

Nowhere would the expression of that intelligence be more widely diffused than in their pottery and especially in the motifs with which that pottery was decorated. One particular motif, the wave pattern (misleadingly labeled in English the "wood pattern") seems particularly relevant. For there, in oscillating ripples, the Ionians would give expression to the very energies at play in that generative period of their evolution. Whether the ceramics in question happened to have originated in Ionia itself or in its new emergent colony to the west, Massalia, matters little, for in both cases the motif underwent a virtually identical evolution. In tracing that evolution, we find ourselves following—quite inadvertently—the vibratory weave of an originating vision. Find ourselves drawn, on oscillation alone, over the threshold of that inaugural occasion.

"For the fuller's screw, the way, straight and crooked, is one and the same."[2] So wrote Heraclitus, an Ionian himself, describing the apparent contradiction of opposites in the inseparable flow of the singular: that of Being. No statement more accurately describes the energies inherent in that undulant pattern. Written at the very moment the Ionian decor had come to free itself from cer-

tain "orientalizing" characteristics (manifest in static, geometric motif), it expressed the fluidity of the new philosophy. It spoke of a universe in continuous motion, change, in which "all things are driven through all others" by a single governing principle.[3] The waves, indeed, illustrate that principle. Existing in a harmony of "opposing forces," they, like Heraclitus's lyre, vibrate to a series of tensions and releases.[4]

Studying this particular motif in regional museums or in those rare archeological papers devoted to the Hellenization of Gaul, one is struck by a curious phenomenon. In the sixth century B.C. —at the beginning of the Ionian colonization of Marseilles—the wave pattern tends to oscillate freely, to ripple in a loose set of seemingly erratic intervals. Labeled by the archeologists as oblique, uneven, or irregular, it's generally dismissed by those specialists as something primitive if not, quite simply, maladroit. But is it? We seem to be in the presence, rather, of a graphic rendering of that very flux Heraclitus himself first evoked. In the presence, that is, of an incipient—emergent—energy flow, interpreted here through an artisanal medium. What the potter's hand, incising the freshly thrown clay, had delineated.

Flux, flow: we're reminded of the Greek infinitive, rhein , which describes this very movement, and which Emile Benveniste qualified as the "essential predicate" in Ionian philosophy from the time of Heraclitus onward. In Benveniste's luminous essay, "La notion de 'rythme' dans son expression linguistique," we learn that rhein , as generatrix of rhitmos (from which we derive rhythm ), signifies the manner by which objects in nature are deployed, positioned, momentarily situated. In combining rhein (to flow) and the suffix-thmos (suggesting the mode by which a particular action is actively perceived by the senses), we arrive at the signifier for an immensely rich, immensely variable quantity. Rhitmos , at this diacritical moment in Western thought, isn't to be

Examples of the wave pattern in Ionico-Massalian pottery.

Courtesy Fonds Fernand Benoit, Palais du Roure, Avignon.

seen as some idea, some fixed, inalterable concept, but as the fluid architectonics of each given instance. "It designates form," in Benveniste's words, but "form as shaped by the mobile, the moving, the liquid; as something that possesses no organic consistency of its own. It is more like a pattern drawn across water, like a particular letter arbitrarily shaped, like a gown, a peplos casually arranged, or a sudden shift in an individual's mood or character." It constitutes form, certainly, but form as something "improvised, provisional, modifiable."[5]

How close this definition comes to describing the archaic wave pattern itself, so quickly dismissed by the specialists as something "irregular." To the contrary, the potter was giving free play not to his own whims and fancies but to the vibratory flow of yet unregulated energies. He was, we might call it, expressing himself in an ontological script, the calligraphy of Logos itself. The parallel lines he traced appear to rush, undulant, out of some immediate if invisible point of origin. They rise, plummet, exult—convulsively—about the flanks of some terra-cotta vase like a freshly released creature. If anything, they seem alive .

Here we're very close to a vision of existence that, after being rapidly suppressed, would have to wait two and a half millennia to see itself reasserted. How familiar it sounds to readers of Nietzsche's Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks or—more immediately—Heidegger's Being and Time . We might be reminded, too, in the realm of modern aesthetics, of Klee's definition of art as Gestaltung : as form in the perpetual process, or act, of formation. Or Olson's interpretation of the poem as a "high-energy construct" in which "form is never more than an extension of content."[6] These, indeed, are archaic canons. Together, they share a common vision. Within that vision, the world (and the works by which that world is made manifest) erupts continuously out of an irrepressible point of origin. An iridescent chaos, as Cézanne once put it: a place

from which the virginity of the world might, once again, be experienced. An area that antecedes reference, coordinates, points of orientation, that refuses any form of pre-established measure in its protean capacity to generate—and perpetuate—all such measure.

The waves writhe. About the rims, shoulders, hips of so much earthenware, the pattern thrives in each of its fresh releases. As conceived by artisans, it celebrates the preconceptual. It speaks of a world that hasn't yet fallen under the dictates of human determinism. Spontaneous, convulsive, this original wave pattern, however, will adorn Ionico-Massalian pottery for a remarkably short period of time. Under the effects of an emergent humanism, the pattern itself will rapidly harden. Codified into bands of identical, oscillating units, it will vanish altogether as an expression of emergence. By the fifth century B.C. , it appears as little more than a script confined to mechanical repetition. It has fallen victim, in short, to number.

This evolution followed that of philosophy itself. Within a half-century—from the time, that is, of Heraclitus and most of the pre-Socratics to that of Socrates—rhitmos would find itself redefined in an increasingly narrow manner. Plato himself qualified rhythm as "the order of movement" manifested, say, by a dancer in measured, predetermined intervals. One had already entered the reign of metron . From an elemental vision of emergence, notions of number, of discrete units of articulated time, increasingly predominated. The potter's hand could only follow. Indeed, in Henri Maldiney's words, "measure had introduced the idea of limit (peras ) into the midst of the limitless (apeiron ). Between these two extremes, the destiny of rhythm itself would unfold: would die, finally, from inertia, dissipation."[7] Would die, finally, with the Latin cadare, cadentia , the mechanical breath-fall of our own acquired notions of "cadence."

With the ossification of the wave pattern, we become witnesses to the cryptic birth of a certain technological ideation. Traveling from Logos to Eidos , we reach—in an amazingly brief period of time—the very thresholds of concept, an order of thought that no longer needs to acknowledge its own origins, inception, emergence. In recognizing no antecedent, it cannot, in turn, generate sequence, translate energy. Static, self-sufficing, it can do little more than replicate—ex nihilo —its own formulations.

How much of modern conceptual art today celebrates this very immobility, exults in its own truncated vision? "Sad," Schiller will warn Hegel, "the empire of concept: out of a thousand changing forms, it will create but one: destitute, empty."[8] We see it all too often in galleries; read it, over and over, in postmodernist journals; find ourselves increasingly exposed to an astonishingly similar, astonishingly rigid vision of existence. An art so deliberately sepulchral can only be, indeed, an end-art. Can only be, finally, a vain exercise in the service of a terminal aesthetics.

Here, though, we're not concerned with endings but beginnings: with that inaugural instant in Western civilization that would recognize itself not in its mirrors but its waves, in the irrepressible flow of an inexhaustible dynamic: that of Being. Vectorial by nature, it would express itself in a multitude of ways. The archaic wave pattern happens to be one such way. As a signature, it ripples freely across the flanks of so much salvaged terra-cotta in its own inimitable script. It speaks, as it goes, pure transmission.

How can we help but marvel, discovering one of those potsherds ourselves? At Saint Blaise, for instance, after the winter rains, a fragment may inch its way to the surface out of some excavated cross section. Examining the supple lash of its undulations whipping their way across this all-too-abbreviated fragment, we might find ourselves wondering what is it, exactly, if not current itself. If

not the still-living filament to a lost luminosity. If not, indeed, the limpid inscription that has somehow survived (like Heraclitus's fragments) its vernal discourse. We might find ourselves asking these questions as we hold the potsherd between thumb and forefinger. Hold it like some kind of key. Hold it like some very particular kind of key to some very particular kind of door. The door, alas, has long since vanished.

Tracking Hannibal

Dum elephanti traiciuntur . . .

Livy, Ab Urbe Condita

I

There's a word missing. And, without it, without that single, indispensable qualifier, we'll never be entirely free of guesswork, idle speculation, academic conjecture. I'm not referring, here, to some ontological puzzle touching on, say, the nature of existence, but the location of a particular event at the outset of the Second Punic War: namely, the exact point at which Hannibal crossed the Rhone. Does it really matter, though? Who in fact cares about an event so relatively minor within the entire breadth—unraveling—of history itself? Why should this particular moment in the late summer of 218 B.C. be the focal point of such lavish attention? Such meticulous, painstaking examination?

There's a word missing. And history, a system that tends toward closure, irrefutable fact, finds itself in this instance confronted by an omission, a lacuna. Finds its tightly woven fabric momentarily rent. It may well be the underlying cause, indeed, of so much obsessive attention, why innumerable hypotheses have been emitted in regard to Hannibal's exact point of crossing.

The lacuna in itself draws the scholar's curiosity with all the involuting magnetism of some low pressure zone, some cyclonic eye. For this tiny textual oversight, this minor omission in the running narrative of Hannibal's exploits, has generated an entire literature based on interpolation alone. History, we come to realize, has a horror of omissions. It comes rushing, each time, into its gaps, silences, hiatuses. Comes rushing with a scarcely concealed voracity.

From Narbonne to the Rhone crossing, Polybius is explicit: Hannibal's armies had marched one thousand stadia (approximately 18 5 kilometers) to reach the banks of the river. But which banks, exactly? We can be certain that he'd taken, in crossing Languedoc, the Via Iberia (later known as the Via Domitia, a Roman Praetorian route). Passing through the territory of the Volcae, whose capital was Nîmes—a final stage-point on the Via Iberia before the Rhone itself-he would normally have reached the crossing at a level with Beaucaire. But did he, in fact?

It's far easier to imagine Hannibal and his armies than to fix their exact location at any given point. Easier to imagine the clouds of late summer dust that must have arisen from the trampling of fifty thousand foot soldiers, nine thousand Numidian horsemen on horseback, an inexhaustible quantity of pack animals, not to mention the soft, waddling gait of thirty-seven mounted elephants, striking terror as they went into the heart of incredulous Gaul. As for Hannibal, his name alone—"By the Grace of the God Baal"—speaks eloquently enough. Riding one of those immense, ungainly creatures, one can readily imagine that twenty-six-year-old warrior—already considered a genius in the dark art of strategy—as if enlightened from within. We have Livy's account (drawn, no doubt, from some Carthaginian source) of Hannibal's dream: how, only months earlier, a youth of divine aspect (iuuenem diuina specie ) had appeared to Hannibal in his sleep, sent by Jupiter himself to guide

the young warlord on his march into Italy.[1] With Baal behind him and Jupiter—like a star—ahead, how could Hannibal help but feel enlightened, protected as he was by those invisible forces?

From the outset, he had three major material preoccupations. First he'd been obliged to bide his time, to camp with his immense armies in Cartagena (Carthago Novo), Spain, until the spring crops had been harvested and his troops adequately supplied with rations. This had meant delaying the entire campaign until late May at the earliest. Next came the Rhone crossing. At no point in his immensely perilous journey would his armies be more exposed, open to attack. In September, he knew, the Rhone's waterline would be at its lowest, and the river itself at its most amenable. No moment could be better chosen. Last came the greatest obstacle of all: the Alps, the imperious gateway onto the italic plains and, ultimately, Rome itself. These, as Hannibal well knew, had to be crossed before the Pleiades had set in the western sky (occidente iam sidere Vergiliarum )[2] —before, that is, the first snows fell.

Considering the scale and daring of such an adventure, why should we—twenty-two hundred years later—confine ourselves to the petty details of one specific instance: those hypothetical crossing points in Hannibal's vast dé-marche? I find myself asking this question as I, too, enter the puzzle, following the banks of the Rhone this morning—geodetic survey maps in hand—traveling northward from the lowest conceivable crossing point, inspecting each alternative, each purported site, as I go. What, though, could anyone add to those endless pages of supposition already written, that endless catalog of postulates? I stare at the river, the perfectly flat, imperturbable slip of its pearl-grey waters, asking myself that very question. What's left to be determined?

The Greek historian, Polybius, is both our first and our most indispensable source of information. His Historiae , covering the full fifty-three-year span

of the Second Punic War (beginning with its causes and concluding with Rome's total subjugation of the Carthaginian empire) was written only seventy years after Hannibal's astonishing blitzkrieg across Gaul. Drawing heavily on documented reports left by Hannibal's own historians, on eyewitness accounts, and on his own footwork (he would trace Hannibal's entire trajectory himself), Polybius was an utterly faithful, if somewhat verbose, chronicler of these events. Indeed, his own account often reads like an "engineer's report," as one modern historian put it.[3] Why, then, hasn't Polybius himself furnished us with the missing word, the long-vanished locative? Given his respect for painstaking accuracy, why didn't he fix the exact crossing point forever in his written Historiae ? Polybius himself supplies us with an answer. In Book 3 he writes: " . . . in unknown regions, the enumeration of place names has, I feel, no more value than words devoid of all meaning, than a mere babble of sounds."[4] Writing in Greek for readers totally unfamiliar with the geography of those scarcely explored regions, Polybius simply deleted most place names altogether. Instead, he employed what might be called spatial indices: cardinal points to indicate direction, and either stadia (a unit of length) or marching days to indicate distance. Both, of course, could be readily comprehended by his Greek readers; his descriptions were totally exempt from meaningless toponym.

What, then, about the documented reports left by Hannibal's own historians, those who'd accompanied the warrior throughout the various stages of his vast expedition? Polybius himself had drawn freely from these Carthaginian sources and had even berated them in his Historiae for cluttering their own accounts with toponyms, those place names devoid of any significance whatsoever. One thinks especially of Silenus—one of seven known Carthaginian sources—who was not only Hannibal's personal historian but also a companion-in-arms in

his march across Gaul. Certainly Silenus would have named the exact crossing point and the battle that immediately ensued. And, most certainly, he had. But along with the six others, Silenus's accounts have totally vanished. Nothing remains of their work except their names. History, here, has deprived us of everything but the vacuous signature of its historians.

Silence is a relative quality: there are degrees of silence just as there are degrees of sound. Here, for instance, with the loss of these seven contemporary eyewitness accounts, the silence of history itself has deepened, amplified. We've traced the event down to its most immediate, recorded sources and discovered that the sources themselves have disappeared. We have no choice but to move forward in time, to seek out classical historians who still happened to have access to those works, hoping, as we do, to detect some thin trickle of evidence.

Coelius Antipater, a Roman annalist working at about the same time as Polybius, compiled a monograph on the Second Punic War in seven consecutive volumes. Considered a highly reliable source by Valerius Maximus,[5] it must certainly have contained our missing word. But Coelius's monograph has, alas, vanished as well. Like the works of those Carthaginian historians, it too has entered a level of silence that we can only consider as absolute. Searching for a scrap of historical information, we've encountered nothing but deliberate deletion on Polybius's part and the successive effacement of recorded testimony owing to the barbarity or brute indifference of the Dark Ages that followed.

There remains Livy. Considered along with Tacitus and Sallust as one of Rome's greatest historians, Livy wrote an account of Hannibal's expedition in Book 21 of his vast, sweeping, eight-hundred-year Ab urbe condita (History of Rome). The pages of that book contain some of the most celebrated passages in all of Latin literature. They belong, indeed, more to literature than

history, as Livy—with an aristocratic disdain for verifiable fact—worked his narrative to a high rhetorical polish. Drawing freely from not only Polybius and Coelius Antipater but also from the seven vanished Carthaginian histories, he conflated his materials into a single flowing narrative, a flumen orationis of his own. For all its beauty, however, it leaves us guessing. Rarely citing the names of his historical informants, Livy offers up a "cut-and-paste" version—as Sir Gavin de Beer put it—of Hannibal's great exploits.[6] We'll never know, of course, which parts originated where. With Livy, we're continuously at the mercy of amalgamated material and, inevitably, this material comes to contradict itself. Furthermore, if Polybius chose to delete place names in favor of spatial indicators (distance and direction), Livy did exactly the same, but for the sake of tribal territories. He located events in history according to whose territory in which they happened to occur. Hannibal crossed the Rhone, he tells us, in the land of the Volcae. Alas, the "land of the Volcae" designates an area far too extensive, lying on either side of the Rhone, to lend itself to anything more than exacerbated guesswork, shallow speculation.

There's a word missing: a single, precise, irrefutable place name. And, in its absence, the question itself remains posed—history itself suspended—over the geographical particulars of a few dusty, tumultuous days, twenty-two hundred years earlier.

Here I am, then, reading Polybius along the banks of the Rhone in my own rudimentary Greek, murmuring phrases to the waters before me, as if the waters themselves could be awakened from their somnolence, stirred—on syllables alone—from centuries of flat, placid self-absorption. I'm at Arles, this morning. Or, rather, at Fourques, facing Arles across the waters of the Rhone which are moving, here, at no less than two meters a second. A traditional cross-

ing place since protohistoric times, Fourques-Arles represents the lowest—southernmost—point yet proposed as that of Hannibal's. In fact, in the absence of a single certifiable crossing, more than thirty carefully researched, thoroughly plausible locations have been proposed. From Seneca to Napoleon Bonaparte, the hypotheses abound. One of them, of course, is correct, for certainly Hannibal must have crossed somewhere. But where, exactly? Grosso modo , there are two schools of thought: that his crossing point was fairly close to the sea (thus, possibly, at Fourques-Arles) or that it was as far removed from the sea as Hannibal could reach within the allotted marching time. For the Carthaginian had to contend with not only a vast army of hostile Gauls, already massed on the opposite bank of the Rhone, but also a Roman consular force, led by Publius Cornelius Scipio, which was hard on his heels. If Polybius suggests, on three separate occasions, Hannibal's proximity to the sea throughout these events, he also tells us that Hannibal crossed the Rhone at a distance from the sea equivalent to "four marching days" (3.42.1). Here he enters into complete contradiction with himself and introduces one of the errors that will set historians astray for two millennia. Which of these two versions should we believe? Furthermore, when Polybius indicates "four marching days" from the sea, we have to ask ourselves, once again, from where? From Fos, the Roman Fossa Maritima, or some other coastal station, further to the west? As to the marching days themselves, how should we calculate that distance? Scipio's full-sized consular force, we know, moved at a rate of fifteen kilometers a day, whereas Xenophon indicated a rate of twenty-two kilometers a day for Cyrus's legions, and Caesar himself boasted of nothing less than twenty-seven kilometers a day in his own conquest of Gaul. Which of these distances, finally, constitutes a marching day in Polybian terms?

If the hypothesis of a crossing point somewhere near the sea (for example,

Fourques-Arles, or Beaucaire-Tarascon) has the advantage of a certain in-eluctability—these were traditional points of crossing, fully equipped with ferries, rafts, coracles—a point further to the north satisfies more fully the descriptions we have of Hannibal's immense strategic cunning. Livy clearly stipulates (21.31.2) that Hannibal, in removing himself as far as possible from the coastline, felt he might avert the Roman forces altogether. Even better, we have a single lapidary phrase from Zonaras: "Hannibal himself always avoided the obvious way."[7]

Whichever hypothesis we tend to support, we find ourselves confronted by inherent contradictions. The closer we read—the more exacting our examination—the more enigmatic and ambivalent our findings. For each grounded argument, there's a counterargument; for each proof, a refutation. Have we entered, here, some kind of parable, some esoteric object lesson, say, on the nature of knowledge itself?

What, in material terms, am I looking for this morning? First, an area along the west bank of the Rhone broad enough to allow an army of sixty thousand men to mass in martial order and prepare their attack upon the facing bank. In short, a vast staging area.[8] Part of that preparation would include the felling of trees (poplars mostly) for the sake of constructing, in haste, the rafts, barks, and pontoons necessary for that crossing. Next, there'd have to be a relatively flat plain en face . Hannibal wouldn't have given his enemies the advantage of a natural shelter behind rocks, ledges, hillsides; he would have forced them down onto the same merciless level as himself: that of the riverbank. He would have chosen, quite deliberately, his own beachhead.

Polybius tells us that several days before the attack, Hannibal (as the inventor, most likely, of commando tactics) sent Hannon, one of his most trusted generals, two hundred stadia (thirty-seven kilometers) northward with a con-

tingent of troops. There, where an island lay in the midst of the Rhone, the waters would be at their widest, and, consequently, their most shallow. Hannon's troops could swim across at this very point, floating on their wooden shields, dragging behind them bloated goatskins laden with their impedimenta.

I needed to locate an island, then, situated a certain number of kilometers north of two facing plains: one on which Hannibal's troops might have been deployed; the other on which he would have engaged the Gauls in combat. Altogether, these three locations constituted the geographical determinants by which I might postulate Hannibal's crossing point. Furthermore, there was a fourth factor: Hannon, having crossed the Rhone and landed on the opposite bank with his swift, lightly equipped, elite corps, sent Hannibal a smoke signal (ex loco edito fumo , Livy 21.27.7) from a hill just behind or beside the battle site itself. He did so, according to Polybius (3.43.1), only a moment before daybreak. With that signal, the battle commenced. In a conjoined maneuver, Hannon took the Gauls by surprise from the rear as Hannibal, in a frontal attack, led a first wave of light cavalry across the river. By nightfall, we read, Hannibal's victory would be assured.[9] Firmly established on the east bank of the Rhone, nothing but the Alps would stand between the Carthaginian and his ultimate ambition: Rome itself.

Along with my three other determinants, I had to locate the hill "just behind or beside the battle site." All four of these locations had to coincide with one another, mesh topologically. So, starting at Fourques, I set out. Carrying battered Loeb Classic editions of both Polybius and Livy, a sheath of notes I'd taken from the works of the specialists, and a complete set of geodetic survey maps covering the lower reaches of the Rhone valley, I made my way gradually northward. I was delayed at the outset by a ground fog that kept me from taking clear cross-river sightings, but a mistral arose by nine that morning

which virtually delivered the landscape, rendered it crystalline. Along with the mistral came the sun. A clear, mid-winter day in Provence now lay before me in which to visit a whole host of proposed sites, to verify or dismiss each of them as I went.

From the survey maps alone, I was well aware that any number of islands lay in the middle of the Rhone; several of them could easily qualify as the one that Hannon crossed with his small troop of commandos. I could readily discern, for instance, the Ile de la Barthelasse off Avignon, the Ile de la Piboulette between Ardoise and Caderousse, and—further to the north—the Ile du Malatras in the vicinity of Pont-Saint-Esprit. Indeed, each of these islands has been proposed as Hannon's by a number of specialists over the years. But did any of them lie thirty-seven kilometers north of a pair of facing plains? And, if so, did the plain on the opposite (eastern) bank possess an overhanging ledge or hillock from which a smoke signal—undetected by an enemy, just beneath—might have been lit?

After traveling over ninety kilometers northward to Pont-Saint-Esprit, inspecting each postulated site, triangulating, as I went, between the various topological determinants involved, I came, at last, to an irrefutable conclusion. None of the sites proposed or suggested corresponded with the existent physical realities. If nearly all of them satisfied three of the given characteristics, not one of them coincided with all four. If, for instance, I found a number of matching plains, several of which lay thirty-seven kilometers south of an island, I never found the rock overhang or hillock befitting. Or, if I did, I wouldn't find the island or the plains in their appropriate contextual positions. There was always a piece missing in this four-piece puzzle I was playing with history. Or was history, in fact, playing with me? Laying out false directives for the sake of concealing some cherished moment all the more consummately?

II

I would only belabor the issue by extending my area of research into the Alps themselves. For there, the same textual problems exist, but multiplied a thousandfold. Perhaps no single event in Roman antiquity has given rise to so much controversy as the exact passage Hannibal took in crossing the Alps. Be it the Rhone or the Alps, however, it's curious, I find, that each of these unspecified points involves passage. Each involves a single, perilous, all-determinate moment of territorial penetration in which the Carthaginian entered—forced his entry—into an entirely new region. Why, then, have these points, so crucial in themselves, gone unnamed? Even Livy, writing only a century and a half after Hannibal's passage, remarked that there existed amongst his contemporaries serious doubt as to which Alpine pass Hannibal actually took (ambigi quanam Alpes [Hannibal] transierit , 21.38.6). Dennis Proctor, in his brilliant study, "Hannibal's March in History," refers to the silence of those contemporaries. "Varro, Pompey, Strabo, Cornelius Nepos, Appian, and Ammianus Marcellinus," he writes, "apart from Polybius and Livy themselves, all mentioned Hannibal's pass in one context or another, but not one of them gave it a name or referred to it in any other way than as Hannibal's pass . . ."[10]

This curious lacuna generated doubt, confusion, or a certain embarrassed silence on the part of those early historians. Even more it created, with time, a plethora of speculation. A first monograph on the subject appeared in 1535, followed, in each century, by hundreds of refutations, correctives, counterproposals. Scaliger, Casaubon, Gibbon, Napoleon, and Mommsen, among many others, would make their contributions. None, however, would entirely concur. Even today, come late October and the proverbial "setting of the Pleiades"—the moment, that is, of Hannibal's crossing—the Alpine passes are visited by

a seemingly inexhaustible number of prospecting Hannibal scholars. What do they expect to find at those altitudes? Having already compared the irreconcilable textual differences between Polybius and Livy, they'll attempt to determine the material conditions prevalent, at that moment, at some specific col. Measuring, say, the exact angle of each feasible slope or the "adhesion potential" of a hypothetical four-ton elephant on the freshly fallen snows of that slope, they'll arrive, quite often, at some entirely new hypothesis of their own. Questioning forest rangers, chamois hunters, road maintenance workers, priests in their mountain parishes, they'll come to ever new conclusions. Given that there exists more than forty negotiable passes between the Great Saint Bernard and the Col de Larche (the passes themselves ranging from mule trails to tarred roads), and that most of those passes possess a variety of approach routes of their own, the possibilities are virtually limitless. So, too, is the number of hypotheses advanced.

There is, quite clearly, a word missing. Or, more exactly, words missing from the pages of those first, founding, historical documents. Here, as elsewhere, history is riddled. Instead of a locative, we discover, in its place, a lacuna. Where an all-determinate event in history occurred, we're given, within the running fabric of those earliest narratives, a deliberate deletion in one case, a careless oversight in another, a succession of eloquent silences in yet others. Why, then, haven't historians simply accepted the good advice, say, of Marc Bloch? "Having explored every given possibility," he suggested, "there comes a time when a scholar's greatest duty is simply to confess ignorance and admit to it openly."[11] Why, to the contrary, this insistence? Why have an endless number of trekkers tested one col after another, written—on speculation alone—an incalculable quantity of monographs touching on Hannibal's "true Alpine pass," or spent long days, as I have done, attempting to determine the exact point at which the Carthaginian crossed the Rhone?

"The problem, here," as Ulrich Kahrstedt, a German classicist, astutely observed, "isn't topographical so much as historico-literary."[12] And, as I've already suggested, the nature of history is one that tends toward closure, conclusiveness, a seamless weave of sequential events. Most of the time, we feel ourselves an integral part of that continuum. That unbroken pattern. When, however, that pattern undergoes rupture, suffers hiatus for even the briefest instant, a certain intellectual anxiety results. Call it a zone of mnemonic instability. The void, we feel, must be filled; the lacuna, rectified. We come rushing into those areas of omission with a fervor bordering on the obsessional. Like bees, their metabolism stimulated at a certain given temperature, we swarm to the indeterminate: attempt to enter the very vocables that history, inadvertently or not, has left open.

Hannibal was fortunate, I find myself thinking. It's already late afternoon, now, as I gaze across the Rhone at one of the last hypothetical crossing points and muse on that doomed twenty-six-year-old warrior. On the opposite side, light is striking the ruins of a medieval watchtower—this very instant—a rich, carmine red. Yes, Hannibal was fortunate, for he'd managed to escape—at certain critical moments—his own historians. Those moments, and most notably the two perilous episodes involving passage, penetration, and the conquest of an entirely new territory, remain as if suspended, abeyant. They belong to a blank language. An empty script. Historians will go on postulating, speculating, demolishing one thesis for the sake of advancing another. It won't matter. As I watch the channel buoys bob in the draft of that deep, unremitting current, I'm fully convinced that that language will remain blank; that script, empty. The book, complete with the inaudible trumpeting of its thirty-seven volatilized elephants, will lie forever open.

What the Thunder Said

for Jérôme Rimbert

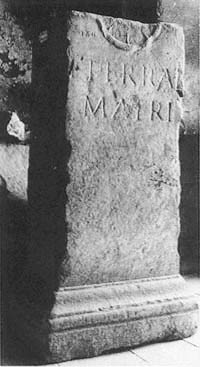

Fulgur Conditum , the inscription reads: [Here] lightning [has been] buried. Altars, stone tablets, commemorative markers bearing that same terse inscription are still occasionally discovered on the barren, wind-blown plateaus of rural Provence. For wherever lightning strikes (drawn, no doubt, by a high level of electromagnetism) there's a likelihood that the Gallo-Roman rites of thunderbolt burial were once practiced. Considered sacred (sacer ), as the very signature of Jupiter himself, lightning was "interred" at the exact point at which it fell. Along with the lightning bolt were buried whatever bits of wood, roof tile, etc. (dispersos fulminus ignes ), that might have burnt in its passage. A small cylindrical retaining wall (a puteal ) was erected around the point itself, the above-mentioned epigraph affixed, an animal (usually a sheep, a bidens ) sacrificed in expiation, and the enclosed ground consecrated by an officiating priest. This priest, a fulguratore , was fully initiated in the art of lightning worship. The ritual itself was immediately followed by an interdiction:

Gallo-Roman altar bearing the inscription Fulgur

conditum: Here lightning has been buried.

Photo by the author.

no one, henceforth, could approach the consecrated area nor gaze upon it from a distance. For it had now become the inviolable territory of Iupiter Fulgerator himself.

The Roman poet, Lucan, has left eloquent testimony to such a ritual. Arrus, we may assume, was the officiating priest in this particular instance:

Arrus gathered together the lightning's scattered fires,

Buried them in murmuring dark formula,

Placing the site, thereby, under divine protection.[1]

These ceremonies, or exhortio , were aimed at eliminating any destructive forces still inherent within the thunderbolt itself, while preserving its sacred character in the shafts of the consecrated earthen wells. Lightning, as divine manifestation, was thus secured within a context of strict sacerdotal observation: its holy fires were ritually "housed."

From classical sources, we have abundant evidence of the awe that these forked fires once inspired. Plutarch, for instance, tells us that whoever happened to be touched by lightning was considered invested with divine powers, whereas anyone slain by one of its jagged bolts was deemed equal to the gods themselves.[2] Furthermore, it was believed that the bodies of those struck dead by lightning weren't subject to decomposition, for their innards had been embalmed by nothing less than celestial fire.

Ultimate nexus between heaven and earth, the lightning bolt has a mythopoeic history that can be traced as far back as the Assyrians. They considered its sacred fire not so much an attribute of their divinity, Bin, as his very manifestation. The same would hold true for the Phoenicians, the Egyptians, and the Cypriots. It is not until the cult of lightning reaches Greece, transmitted no doubt by those pre-Hellenic people, the Palasgi, that the lightning bolt as divine manifestation becomes sema , sign, the personal attribute of an otherwise invisible deity whose reign would now extend over all atmospheric phenomena: Zeus Keraunos.

Undergoing continual changes within Greece itself, lightning worship would reach Rome through the mediation—call it the divinatory agency—of

Etruscan priests. Indeed, these priests, the fulguratores , armed with their notorious libri fulgurales (oracular books in which questions were posed in archaic Latin and answered by these mediators in Etruscan) dominated the Roman cult of lightning worship until the end of the Roman Empire. Even the original Italic figure of Jupiter, thunderbolt in hand, underwent a certain "Etruscification." Originally considered a sky spirit (a numen ) in archaic Roman mythology, he takes on the epithets optimus and maximus under the spiritual tutelage of these mediating Etruscan haruspices. A magnificent temple in his honor was erected on the pinnacle of the Capitoline, commissioned, no doubt, by Tarquinius Priscus and Tarquinius Superbus, the semilegendary twin kings of Rome, reputedly Etruscan themselves. There, the effigy of Jupiter was flanked on either side by the goddesses Juno and Minerva, forming a triadic divinity thoroughly Greco-Etruscan in inspiration.

Whether we're considering this original Italic spirit reigning over all things atmospheric, his elevation to Jupiter Optimus Maximus upon the pantheon of the Capitoline or, much later, one of his Gallo-Roman variants here in the distant hills of Provence, we discover that Jupiter may be identified by two opposing characteristics. The first is evident enough: Jupiter, unfailingly, bears the thunderbolt. Be he Iupiter Fulminator casting the bolt itself, Iupiter Fulgerator revealing himself in its very flash, or Iupiter Tonans declaring his presence in a roll of thunder, he wields, in every instance, that celestial fire. There's a second characteristic, however, that lies as if secreted within the first. As with virtually all archaic representations, characteristics invariably come paired in antithetical sets. The evident conceals the covert, the manifest, the obscure. Modern studies in ethnology, linguistics, and other related disciplines have made us increasingly aware of this particular phenomenon. In 1910 Freud was already writing in regard to words: " . . . it is in the 'oldest roots' that the

antithetical double meaning is to be observed. Then in the further course of its development, these double meanings [tend to] disappear." Same, too, Freud continues, with the "archaic character of thought-expression [found] in dreams."[3] In tracing the etymological origin of a particular word ourselves, how often we'll fall upon one of these antitheses, as if the word itself was embodying, at its very inception, a paired set of opposing signifiers.

In a relatively rare epigrammatic discovery, a Gallo-Roman altar unearthed near Aix-en-Provence bears the inscription Iovo Frugifero : that is, Iupiter Frugifer. Signifying fertility, fecundity, the instigator of harvest, it would appear at first as an epithet signifying an entirely different divinity. How do we get from Fulgerator to Frugifer , from Jupiter wielding lightning, to Jupiter bearing fruit? Obviously, lightning brings rain, and rain, fertility, but how do these two separate, sequential events find shelter within a single all-encompassing vocable? The entire question lies there.

Turning to Roman folk mythology for support, we learn that Jupiter, as the supreme divinity, was celebrated throughout the year not only as master of lightning but also as protector of crops.[4] The Feriae Jovis , festivities dedicated to Jupiter, honored the guardian of the vineyard, the grape harvest, and the winepress. From the Vinalia priora in spring to the Meditrinalia in autumn, Jupiter was invoked at every crucial moment in the vintner's calendar. It was unto Jupiter that wine was offered, rendered, consumed. Other Feriae Jovis that might be mentioned in regard to Jupiter's "parallel identity" include the Robigalia and Floralia of spring. Both of these festivities served as propitiatory rites in favor of the young grain: the first as a protection against blight, the second as a stimulation or encouragement to the kernel itself. Here, once again, Jupiter, master of the heavens, was the ultimate mediator in matters strictly terrestrial, agrarian.

A sculpture discovered in one of Rome's distant colonies in North Africa (near present-day Zaghouan, Tunisia) depicts Jupiter bearing in one hand the inevitable thunderbolt, while in the other, instead of the traditional scepter, a cornucopia filled with fruit. With this sculpture, we have a perfect iconographic representation of the god in all his archaic ambivalence. Both fulguration and fructification find themselves depicted within a single homogenous statement. Together, one and the other are brought to coalesce.

How does Jupiter accumulate, or should we say incorporate, such powers? A line from Pliny's Naturalis historia might help elucidate the deliberately maintained ambivalence of these twin attributes. Pliny, describing the libri fulgurales , writes that the Etruscan fulguratores , charged with all matters pertaining to lightning—be it its observation (observatio ), interpretation (interpretatio ) or propitiation (exhortio )—believed that the lightning bolt itself penetrated the earth to a depth of five feet.[5] This remark is not as insignificant as it may appear. For it tells us that lightning, in the eyes of those mediating Etruscan priests, didn't simply strike and consequently ground itself against the surface of the earth: it actually entered, penetrated the earth as its recipient body. In the language of Eliade, we're in the presence, here, of an "antique hierogamy." Between Jupiter, the "Celestial Thunder God," and Jupiter, the "Bearer of Fruit," we might well be witnesses to that archaic ambivalence mentioned above—that deep-seated androgyny—wherein the god incorporates the qualities of both fructifier and fructified, inseminator and inseminated. Soon, these very qualities will undergo separation. Jupiter will retain his thunderbolt, but an ubiquitous earth-mother will come to reassert her place as the bearer of all earthly goods. Soon, each will be assigned separate, complementary roles in this evolving mythology, this coital enactment "indispensable to the very energies which assure bio-cosmic fertility."[6]

Discussing one of the many engraved inscriptions bearing the words Fulgur Conditum , the late Marcel Leglay made the following pertinent remark:

If lightning is buried with so much care and precaution, its sacred stones deposited beneath an earthen mound that's ringed, in turn, by a boundary wall, and the locus altogether consecrated, is it only for the sake of self-protection? For neutralizing the effects of the lightning bolt? For observing, in short, a taboo? It wouldn't seem so. In my opinion, it's more for the sake of preserving, preciously safeguarding in situ , the source of both the inception and diffusion of that terrestrial fire. The source, indeed, of life itself.[7]

More than fortuitous points of momentary impact, these "wells" of celestial penetration needed to be circumscribed, the divine fire that they'd introduced retained within the entrails of the earth itself. Out of this encounter, all things living, ineluctably, would spring.

By way of illustration, we only need examine a relatively nondescript limestone altar discovered in the region of Nîmes. Here, the two-word inscription, rather than reading Fulgur Conditum , commemorates in stately Roman capitals Terra Matri . Just over this inscription lies engraved the truncated half of a wheel. The emblem of the Celtic god Taranis, this wheel designates thunder. As Jupiter's Celtic counterpart within that widespread family of Indo-European divinities, Taranis's attribute isn't the lightning bolt, but its sonorous aftermath, the hollow thunderclap. The wheel, in the roar of its iron hoop over cobbles, serves as a perfect mimetic signifier. Even Taranis's name, drawn directly from the Celtic root, tarans , designates nothing less than thunder itself. Together, we have, reunited in that simple, somewhat austere altar, the two fundamental protagonists in this cosmic drama: heaven and earth; fire and the ground it fecundates; celestial father and the now distinct terrestrial mother, represented in pure symbiosis.

The wheel, attribute of the Celtic thunder

god Taranis, represented in direct relation

to Mother Earth, Terra Matri.

Photo by the author.

Dedicated to those two indissociable forces, the altar helps clarify the meaning of the Gallo-Roman cult of lightning worship. Clearly enough, the burial of that celestial fire was a means of conserving its procreant energies within the sacred interiors of the earth itself. In a dialectic of opposites, the altar celebrates the indispensability of each within the cosmic contextuality of

both. Furthermore, it tells us, in no more than two words and a single iconographic device, exactly "what the thunder said."

In the high barren wastelands of the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, lightning continues to fall in the same areas where Gallo-Roman Fulgur Conditum inscriptions are still occasionally discovered. These discoveries aren't fortuitous. Despite the popular dictum, lightning not only strikes twice, it strikes the same location repeatedly if that location happens to be, as here, on raised ground and rich in ferromagnetic deposits. Lightning, in these parts, falls frequently. And if, in the past two thousand years, its "entry" no longer receives the kind of consecration it once enjoyed from the hands of officiating fulguratores , we might consider, at least, yet another form of reception. For lightning, the sheer, unmitigated experience of lightning, continues to provoke in the subsoils of our own psyche an inexpungible sense of awe. Devoid now of all ritual, the sublimating effects of all mythopoeic projection, it continues to arouse, nonetheless, the kind of dread and reverence that's always been its due. Ambivalent, provocative, it goes on striking at our deepest, most dormant levels of consciousness. Yes, lightning keeps falling. And its fires, perforating the frail armor of late postmodern rationality, continue to instill, enlighten. Continue to nourish the most fertile regions of our imagination with so many successive bolts of pure, unprogrammed luminosity.

Aeria the Evanescent

for Tina Jolas

There's a lost city in Provence named after air itself: Aeria. A polis to the Greeks, a civitas to the Romans, Aeria must have been of considerable size and located at an exceptional altitude. The Greek geographer, Strabo, mentioned it along with Avignon and Orange and described the site as something "altogether aerial, constructed on a raised promontory of its own."[1]

How could such a sizable, protohistoric city (it was founded, apparently, by the Celts) simply disappear, one wonders? For Provençal historians it represents a major enigma and a source of unending polemic. Scarcely a year passes without the publication of some article, pamphlet, or documented field report offering "at long last, irrefutable evidence" as to Aeria's exact location. In reading these reports one comes to feel that Aeria might have been anywhere, everywhere, nowhere at once.[2] There's hardly a single raised, windblown plateau evincing the least Iron Age vestige that hasn't been identified as that of the lost city. I have read over fifty such reports written in the past

two centuries and have managed to visit a considerable number of the sites proposed. The results, for the most part, have proved disappointing. Few of the purported "Aerias" even begin to fit the descriptions we've inherited from classical sources. What's more, it's the sources themselves that have been largely responsible for so much idle speculation. Brief, elusive, and highly ambivalent in their own right, they've undergone endless alterations at the hands of successive, often careless, medieval copyists. What, indeed, can they tell us today? Without falling into idle speculations of our own, what can we draw from these materials with any certitude whatsoever? How, in short, can we ourselves come to locate the City of Air?

We learn from Strabo that it lay somewhere between two rivers: the Durance to the south and the Isère to the north. A third river, the Rhone, would have constituted its furthest possible reach westward, while the Alpine foothills that of its potential limits eastward. Thus we can determine that this lost city lay within an area of somewhat less than a thousand square kilometers. We can reduce this figure even further: Aeria, according to Apollodorus, was Celtic,[3] and lay, in Strabo's words, within the confederated land of the Cavares.[4] These people occupied the fertile plains of the Rhone valley and its adjacent plateaus to the east. Rising up over those plains, Aeria must have been visible from a considerable distance and been immensely impressive for travelers such as the Greek chronicler Artemidorus. His mention of Aeria towards the end of the second century B.C. constitutes (along with Apollodorus's remark that Aeria was Celtic) our first topographical source. What else can be said with any certitude? We can safely postulate that Aeria lay somewhere north of Avignon and Orange, the two cities with which it is associated in Strabo's Geographica . Strabo almost certainly named these three cities in geographical order: from Avignon in the south to Aeria in the north. Beyond Aeria, he tells

us, begins a wooded region, rife with narrow mountain passes. This region extends the length of a full day's march (approximately thirty kilometers) to a town called Durio. Of Durio, however, we know absolutely nothing. Nor can we begin to speculate on the identity of the two rivers which, according to Strabo, circumscribed Durio before converging in a single current towards the Rhone itself.

From Durio onward, we've gone thoroughly astray. The location of the town, of the two all-determinate rivers within a shifting landscape of textual incertitude has left us totally at the mercy of hypotheses. Even reduced, now, to an area of less than three hundred square kilometers, we have any number of perched Iron Age oppida from which to choose. Some, of course, can be quickly dismissed because of their insufficient altitude; others, because their table-top summits could scarcely have enclosed a full protohistoric city; yet others, because their profile—even if raised, massive, commanding—couldn't possibly have laid within sight of a major Greek trade route such as Artemidorus must have taken, traveling northward from Marseilles to Lyon.

We've narrowed our possibilities, however; we've reduced our area of prospection to a relatively narrow band of earth running approximately parallel to the left bank of the Rhone and in a region somewhat to the north of Orange. Within this area, several protohistoric sites have been proposed. One of them, the oppidum of Barri, has received particular attention recently from some of Provence's most respected historians. Lying just north of the market town of Bollène, itself traversed by the Lez (potentially one of the two tributaries mentioned by Strabo), the oppidum satisfies a number of conditions that could eventually lead to its identification as Aeria. Rising in an abrupt, vertical cliff over the plains, it commands a spectacular view of the Rhone valley

beyond, as well as a controlling position over the ancient Greek trade route just beneath. Vast, rich in natural springs, and abounding in late Iron Age vestige, the site itself is eminently aerial. Wind-struck, it sits on its raised limestone podium, a good deal closer to the sky above than to the earth below.

A number of counterarguments, however, have come to weaken such an attribution. Despite a maximal altitude of 312 meters, the oppidum itself only rises, in fact, 200 meters over the plains. Would this difference in altitude have been sufficient to support the epithet aerial ? Even more troubling, why would an entire city, a polis , have been located so close to yet another (in this instance, Orange)? Only twenty kilometers separate the two. In classical times, cities couldn't survive without an outlying pagus or canton, a richly cultivated farmland proportionate to the city's population. In this case, the pagus of one would have encroached on that of the other, and their respective sources of sustenance would have been inevitably compromised. What's more, the Celts traditionally founded their cities equidistant from one another. Indeed, the map of Celtic Gaul reads like a continuous network of evenly distributed communities often called, significantly enough, Médiolanum, "The City in the Middle." Here again, the oppidum of Barri is far too close to Orange to satisfy the conditions for such a practice of spatial distribution. Added to this, it must be noted that the oppidum isn't located in the territory of the Cavares, as Strabo specified, but that of the neighboring Tricastini.

Where are we then? Even if we've managed to reduce considerably the number of square kilometers in which Aeria might potentially be located, we're still adrift among hypotheses. Any number of perched, wind-struck oppida could still satisfy our altogether vague descriptions. As for myself, I've often wondered whether I've been searching, all the while, for a location or a locution : whether, that is, I've been looking for a place, an emplacement, a

specific irrefutable locus or—to the contrary—for a word. For a word that would designate, certainly, such a place, but only in the buoyancy, the effervescence of its own iteration. A word that might invoke, within its very vocable, so much stonework and quicklime and smoldering hearth. One, in short, that might incorporate—in its atmospheric particles—an all-impacted, earthbound existence.

Aeria, the Aerial, the City of Air. It would be a sterile exercise in academic philology to speculate on whether the founding radical, aer , originated in Celtic or Greek. Both languages, having common Indo-European origins, shared approximately the same signifier. It would be safe to assume, however, that the toponym itself arose out of the Celtic and underwent, as an adjective feminized to agree with its substantive, polis , a certain Hellenization. As an adjective we find it frequently employed in Greek literature. It appears in Aeschylus's Suppliants , for example, or in its Ionic variant, erea , in Apollonius Rhodius's Argonautica . As toponym, however, it vanished from usage at exactly the same period as the topos it designated. As ever, the two—topos and toponym—would undergo a single inseparable fate. Neither Caesar nor Livy, for instance, mention Aeria in their descriptions of Gaul. If Pliny happens to include it in his list of Gallo-Roman communities within the recently established Provincia, he does so in qualifying the city an oppidum latinum .[5] The term itself suggests that the raised Celtic stronghold had undergone pacification, subjugation: had found itself reduced to a protectorate under the all-powerful pax romana . Soon after, the toponym vanished altogether from contemporary historical record. Neither Mela in the first century A.D. nor Ptolemy in the second include it in the comprehensive geographies that each compiled.

Other towns in Provincia would vanish as well. Of the thirty that Pliny listed, eight would leave nothing more than a name totally detached, now, from

any verifiable location. Among those vanished communities, though, only Aeria would have qualified as polis, civitas : a city, opposed to a vicus , or simple township. Far more pertinent, only Aeria could lay claim to such an immensely evocative, if evanescent toponym. For it's the place name alone that draws us, over and over, onto the raised plateaus of Rhodian Provence, that keeps us searching in one site after another for the irrefutable evidence of some stray inscription, some carved, all-confirming epigraph. Who, after all, wouldn't wish to discover the City of Air? For centuries, erudites, country priests, local aristocrats, or simple curiosity-seekers have combed the region looking for that conclusive artifact wherein place (topographical), place name (toponymical) and vestige (archeological) would perfectly coincide. Many cried out success far too early. Writing in 194, Alexandre Chevalier would claim that "After so many centuries of vain research and laborious investigation, History [sic ] at long last has rediscovered the Antique City whose very existence had begun slipping into pure indifference."[6] Far more perspicacious, the German pre-historian Ernest Herzog would write, "suum quisque locum invenit ."[7] Herzog was suggesting, not without malice, that Aeria could be located anywhere one wished.

There's a danger, of course, in mystifying Aeria, in attributing hierographic powers to its place name. For certainly, it not only existed within a certain ascribable area, it left vestiges eloquent enough to allow for its eventual identification. In the meanwhile, however, its vocable continues to intrigue. For Aeria seems to exist free of the very floors and crypts and quarried vaults in which it once was rooted. In an age of reductive analysis and infallible detection, it continues to resist any classification whatsoever. Doing so, the very name of this elevated, windblown city exercises—we readily admit—a singular fascination. There's safety, we can't help feeling, in its indeterminate status. Its three

weightless syllables have somehow managed to escape (for the moment, at least) any ultimate attribution. Buoyant, suspended, eminently diffuse, the vocable alone, in eluding us, justifies our fascination. Escaping our own stultifying structures, it gives the imagination a late place in which to muse, meditate, linger, if for no more—indeed—than a passing moment.

Votive Mirrors:

A Reflection

The mirror itself was scarcely wider than an eye. Thirty millimeters in diameter, its reflection would have probably included, at its very edges, the line of a cheekbone just beneath, and the floating arch of an eyebrow just over. Within the mirror, we can only imagine, the eye must have come to gaze at its own wobbling likeness. There, undoubtedly, it would have paused, lingered. Around it, on the surrounding lead frame, ran the uninterrupted garland of a propitiatory inscription. For the mirror, the reflected eye and the metallic frame (bearing as it did this running inscription) constituted a sacred offering. Indeed, several of the inscribed mirrors thus far discovered in southern Gaul (essentially in the lower Rhone valley) bear a full votive inscription to a Greek divinity. They're dedicated either to Aphrodite, the goddess of love, or Selene, the goddess of the moon. Together, these two figures reigned over the world of love in each of its multiple aspects, be it erotic, sentimental, magical, or—in Selene's case—propagative.

Frame of a votive mirror dedicated to Aphrodite.

Courtesy Guy Barruol.

We have, then, in concentric order, the eye, its reflection floating in the laminal disk of a glass mirror (one of the first of its kind), and the lead frame itself. The latter, square in outline, encased the pure circle of the mirror. Mirror—and reflection—have long since vanished, of course. We're dealing, after all, with evanescent materials dating from late antiquity: from, that is, the beginning of the second century to the end of the fourth. Nonetheless, minuscule bits of mirror have been detected still wedged between the narrow lead furrows of the frames. This "vitreous debris" has allowed specialists to determine the width of the glass itself (0.5mm in most cases), the method of its

fabrication, and the all-essential undercoat it once received, be it lead, silver, or, occasionally, gold. Above and beyond these considerations, however, their attention has focused almost exclusively on the frames. For it's the lead frames themselves that have offered up such a wealth of information. Thanks to the inscriptions alone, the relationship between dedicator and dedicatee, votary and the object of devotion, can at last be determined. Nearly two thousand years after the fact, something as ephemeral as an individual's quivering reflection in a looking glass can now be interpreted in terms of a lost reciprocity. These were offerings, after all, to one of two specific divinities. As such, they initiated, if not a dialogue, a dialectic between an individual (the votary) and an otherwise invisible entity. Vestiges of a rural and, most certainly, popular tradition, they might be read today as elucidating artifacts.

Votive mirrors existed throughout antiquity. In fact, they're probably as old as mirrors themselves. Poured in bronze, at first, and polished on one side to a high reflective luster, they were far too hard for anything more than the simplest, tool-scratched inscription. Even uninscribed, however, we may assume that they already served as votive offerings to those same two divinities. Traditionally, Selene and Aphrodite were as much recipients of mirrors (as well as rings, earrings, bracelets) as, say, Demeter, goddess of crops, was of miniature metallic hoes, sickles, plowshares. These offerings were all part of what historians have called a "votive contract." Basically, this "contract" functioned in one of two ways: either to invoke the favor of a god or goddess (thus, as a votive instrument), or to thank a god or goddess for a favor rendered (functioning as an ex-voto or acquittance). In both cases, the object, whether mirror or not, served as a token of exchange between a mortal and an immortal.

"I'm giving you this," it suggested, "that you might grant me that." Or, in the latter case, "since you've granted me that, here, take this as a measure of my everlasting gratitude."

With the advent of blown glass in the first century A.D. came the earliest reflecting lenses, no bigger than monocles, such as those encased within these inscribed lead medallions. Whether they evolved into votive objects from women's cosmetic impedimenta (indirectly, that is) or, to the contrary, were especially designed as amulets to serve magical purposes, we may be certain that they belonged entirely to the domain of women. What's more, they were offered by these very women to female deities. We know, for instance, from references to a lost poem by Pindar, that women in love made offerings to Selene, the moon goddess, whereas men in love made offerings to her brother, Helios, the sun god.[1]

Three of the ten votive mirrors dedicated to either of the two goddesses still bear, in abbreviated Greek characters, a full dedicatory inscription. The same maker's name, Q. Licinios Touteinos, figures in each instance, as does the mirror's place of manufacture: Arelate (Arles). We can assume that this artisan was a lead smith (plumbarius ) and most probably a mirror maker (specularius ) as well. We may even consider the possibility that he was an initiate, a priest of sorts, in the mysteries of this amatory cult. Beyond that, however, it would be a serious mistake to confound his name with that of the votary. For the latter's name, unlike the artisan's, is never mentioned. Nor is the name of her beloved. We may infer, however, that the names of both votary and beloved need not have been named, for in the goddess's omniscience (be she Aphrodite or Selene) the names of her immediate subjects were already known, familiar, sympathetically perceived.

The fact that not only the goddesses but also the language employed in these

votive inscriptions happen to be Greek requires a word of explanation. Writes the historian Guy Barruol: "With the use of a foreign language, familiar to only an intellectual elite in the lower valley of the Rhone but most certainly incomprehensible, thus alien, to the average devotee in the Gallic countryside, we might attribute an added power in the use of these objects, richly endowed with magic properties."[2] The use of Greek, in short, added strangeness, mystery, a deliberately orchestrated "otherness" to these votive inscriptions. Barruol goes on to tell us that, in the second and third centuries A.D. , a resurgence in both magical and astrological practices, clearly originating in the Near East, made itself felt throughout southern Gaul. He suggests that a certain "religious syncretism" might have existed between Provincia itself and those distant, still Hellenized encampments far to the east. There, the wives of Roman legionnaires might well have assimilated some of the esoteric practices still observed in those parts and, upon arriving in their recently allotted homelands in southern Gaul, introduced those very practices, still Hellenized, into local forms of worship. As a working hypothesis, this mode of transmission is perfectly plausible. Then, too, it has the consistency of rendering the entire cult—from the ritual itself to its sociocultural dissemination—exclusively female.

Before closing, we might consider the mirrors themselves in yet another light. Aside from being the objects of a rigorous metaphysical barter—the tokens of exchange between a particular votary and her invoked divinity—we might see in their ritual use something far more personal, inclusive, reciprocal. For the exchange implied a communication of sorts. More than simply reflecting, the mirrors disclosed, divulged. Rather than a replicated, visual echo, they offered—out of the depths of the devotee's gaze—a form of response. We know the magic with which reflections, reflecting pools, and the first cast, hand-hammered mirrors were invested, in the founding mythologies of most