Three

The Politics of Meaning and Style

When any one of these pantomimic gentlemen, who are so clever that they can imitate anything, comes to us, and makes a proposal to exhibit himself and his art, we will fall down and worship him as a sweet and holy and wonderful being; but we will also inform him that in our State such as he are not permitted to exist; the law will not allow them. And so when we have anointed him with myrrh, and set a garland of wool upon his head, we will send him away to another city.

Plato, The Republic

Rejecting the politics of the past was easier than rejecting its culture. Many older Bolsheviks, like Lenin and Lunacharsky, saw the cultural legacy as a resource and advocated saving whatever could serve the new order. Progressive culture could be salvaged and reactionary culture discarded. The more radical Proletkultists and futurists, on the contrary, saw the past as dead weight. They considered little worth saving; and even the bits of ore in the dross needed reworking. Neither side of the debate seemed to understand the dilemma fully. Lenin saw the foolishness of radical rhetoric, yet believed naively that the past could be exploited selectively. His wish to preserve the Bolshoi Theater and Tchaikovsky's operas rested on the assumption that a socialist environment would dissolve their old-regime associations. Radicals perceived the sticky web of associations that could entangle a socialist culture built on tradition, but they could not create culture in a vacuum.

Even developing partisan symbols was enormously complex. The Bolsheviks came to power with few symbols of their own. They were not the only revolutionaries in Russia (though they were perhaps the most ardent), and they shared prominent symbols with other parties. The songs, colors, and heroes now associated with the October Revolution were not always exclusively Bolshevik. Though the creation of the hammer and sickle emblem in early 1918 signaled a start, the inadequacy of Bolshevik iconography caused complications in the two major festivals of 1918, May Day and the November 7 anniversary celebration.

Festivals test a symbol more rigorously than other environments do. An emblem sewn on a shirt or decorating a pamphlet lies in a congenial context that supports and complements its message. Symbols displayed in a public festival must compete for attention, and they must drive home their message through a stew of competing symbols and hostile interpretations. The cultural heritage was particularly formidable during festivals, when it was embodied by the city itself. The language and medium of a festival is the city, its people, streets, and buildings. In other instances when the cultural past proved recalcitrant, the revolutionaries dealt with it summarily: paintings were put in the basement, musical scores in the archives, books on the back shelves of the library; but streets and buildings could not be hidden.

The desire of festival planners to celebrate the Revolution in harmonious style was often frustrated by the cities themselves, particularly by Petrograd, the former imperial capital. Petrograd's ceremonial center was dominated by the neoclassicism of later Romanov buildings. In an attempt to overcome the vestiges of autocracy, statues of the tsar, some of which were already slated for removal, were covered with strips of red material.[1] The center of Uprising Square (previously Znamenskaia Square) was occupied by Pavel Trubetskoi's fine equestrian monument to Alexander III. But any tsarist monument was considered an embarrassment, no matter how artistic; so a massive triumphal arch of planks was put over it for the November 7 celebration. On another occasion a tribune resembling a medieval keep was built.

Autocracy's symbols could be concealed or excised, but neoclassicism was a more lasting influence. Faced with a cutback of funds, organizers of the May Day 1918 demonstration in Petrograd settled for a single centerpiece, a float "modeled on a Roman float with a statue of the goddess Freedom in a white tunic, a torch in her upraised hand, standing against a background of the slogan 'Having proudly made it through the centuries of oppression, we celebrate the worldwide May

holiday.'"[2] On a smaller float, labor was depicted allegorically by "th e figure of a woman dressed in a Greek tunic with a torch in her right hand. . . . Sometimes [in later years] the figure of Lady Liberty [zhenshchina svoboda ] was somewhat altered in the new spirit, receiving the dress of a female peasant or worker."[3] Neoclassicism also impinged on the emblems of revolution: in a contest for the Russian Republic's new monetary seal, Sergei Konenkov depicted a satyr and bacchante. The trend continued up to the November anniversary. There were "a depiction of a worker leaping onto a winged horse (the classical Pegasus), angels blowing their trumpets, classical heroes wreathed in laurel, or warriors in helmets and with swords, . . . triumphal arches with columns, sacrificial altars and towers, . . . coats of arms with complete heraldic detail—crests, mantles, and so forth."[4] Tsarist iconography also was apparent: the Legend of St. George was used to depict the Revolution as a "handsome young folk hero with broken chains and a red banner in his hand, liberating a naked woman (Russia), at whose feet a dragon with a crown on its head (tsarism) was coiled."[5]

Although these were festivals of revolution, expressing themes of conflict or disorder led to a certain difficulty: here again the cities were not inclined to cooperate. Few seemed to notice the incongruity; Saratov artists blithely draped the triumphal arches and obelisks erected by the old regime in garlands and bedecked them with emblems of labor.[6] In Petrograd, a city of rigid order and imperial grandeur, the combination jarred some observers. Because decorations harmonized with the city's architecture, the anniversary of the Revolution was not terribly revolutionary. For November 7 Dobuzhinsky decorated the Petrograd Admiralty and surrounding square, which were adjacent to the Winter Palace in the center of town. The square had been the site of popular carnivals in the late nineteenth century, but Dobuzhinsky preferred the building's neoclassical architecture for inspiration. Staying within the facade's stylistic limits, he draped the cornices with red flags and garlands. Naval code was used as a motif, including a ship decorated with sea horses and an emblem of the Russian Republic. Obelisks and spheres were placed on the Admiralty and decorated with a ribbon bearing the signs of the zodiac.[7] Dobuzhinsky's work was a stylization of eighteenth-century ceremonial art. Punin observed:

The October festivities differed little from what the worldwide bourgeoisie did in its own time. The same streets decorated with material, wooden arches, garlands, electric and even just colored lanterns, somehow dully reminiscent of the notorious "days of the tsars," with their gaslit designs and stars. . . . This

happened only because the organizers themselves did not think much about the idea of "celebration" and performed their assignment offhandedly, "with whatever fits." For the foundation of their plan they took the alien and dead idea of "decoration." They found it necessary to decorate the old city and old, primarily "bourgeois" streets.[8]

Yet there were possibilities. Moscow was a city of many architectural styles, which offered artists a wealth of options. The Moscow decorations for May Day, under the direction of the Moscow Commission, matched the city's style without succumbing to its spirit.[9] The Vesnin brothers' work on Red Square and the area surrounding the Kremlin created an appropriate ceremonial center, both solemn and brash. The focus was the Red Square reviewing stand, "a monumental three-tiered tribunal with an enormous wreath of fir branches. . . . Bright purple banners and panels clashed with black ribbons of mourning."[10]

The Conversion of Symbols

Festivals were a recollection of the past; but to avoid ensnaring the new culture in the old, the past had to be remembered selectively. Such was the radicals' compromise: the artistic heritage could be exploited, but only on the terms of the present. The issue was not just theoretical, at least not in the theater, where a dearth of new plays brought proletarian culture to a halt. Blok proposed searching the censors' archives for quality plays suppressed by the tsarist bureaucracy; but he found to his dismay that there were none.[11] Kerzhentsev proposed tackling two problems at once by rewriting the classics to fit contemporary needs.

The present day increasingly forces us to realize that we still have no new repertory, that the creation of plays, if only by reworking and adjusting them, is essential.[12]

Some fine plays have become absolutely unacceptable, for instance, because of their reactionary (by today's standards) tendencies. Why not change the authors' intentions and give the plays meanings that will find resonance with the contemporary audience?[13]

The problem of the new culture could be solved for the time being by the old, by taking the classics and resetting them in a revolutionary context.

Proletkult was a leader in bringing these remakes, or peredelki, to the

stage. Ivan Krylov's fable The Quartet was remade by the Moscow Proletkult into A Conference of the Entente on May Day 1919; "the monkey . . . [became] a Frenchman; the goat was an American; the bear an Englishman; and the ass, an Italian. Instead of Krylov's sparrow [the raissoneur ] there was a worker with a hammer who dispersed the foul musicians whose 'scraping and strumming' had made the whole world sick. Another Krylov fable, The Slaughter of the Beasts, was restaged as a satire about priests, capitalists, policemen, 'high-society' ladies, and their associates."[14]Peredelki could be quite topical. Mikhail Glinka's Ivan Susanin (A Life for the Tsar ) was reset from the Time of Troubles to the 1920 Polish-Russian War, with its original patriotic sentiments unaltered.[15] And five years later, on May Day 1925, the Maly Opera would perform Giacomo Puccini's La Tosca as The Struggle for the Commune .[16]

Clearly, remakes could be overdone, but the method also brought positive results. Meyerhold's third-anniversary (November 7, 1920) production of Verhaeren's Les aubes, in which fraternizing at the front leads to a revolution (the revolution was Meyerhold's addition), was striking and original. On May Day 1919 in Kiev, Konstantin Mardzhanov, one of prewar Petrograd's leading directors, produced Lope de Vega's Fuente ovejuna as a revolutionary spectacle.[17] Scenes of the royal court (which were abbreviated) and the peasant village were placed on opposite sides of the stage and contrasted by acting style and lighting. As Evreinov had done in the Ancient Theater, Mardzhanov stressed the theme of popular struggle against oppression. The king and queen were, in the revolutionary version, identified as the oppressors. The restaged ending of the drama included a rebellion and victory; and soldiers present at the premiere marched straight from the theater to the front.

Nor was music neglected by the new order. On November 7, 1918, at the Workers' Soviet Opera (the former Zimin Theater), Theodore Komissarzhevsky transferred the setting of Beethoven's Lenore[18] from Spain to revolutionary France; cuts were made, revolutionary speeches added, and the whole thing was renamed Liberation .[19] A piece of music could be given new meaning simply by changing its context. Scriabin, although he had died in 1915 and was never associated with the Bolsheviks, was enjoying great popularity in 1918. His symphonic poem Prometheus (a figure dear to revolutionaries) was performed in the Bolshoi, with a curtain by the artist Aristarkh Lentulov that provided a visual complement to the music.[20] The Bolshoi, which had not welcomed Bolshevik management, was trying to catch up on some of the new

themes invading Russian theaters that year. The Scriabin performance was only part of an evening "unified by the theme of rebellion, of the people rising up in the name of reason, light, and liberty."[21] It was followed by the Veche (Popular Assembly) scene of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's The Maid of Pskov, and the last piece of the evening was Aleksandr Gorsky's ballet Stenka Razin .

For artists searching the past for a myth of popular rebellion to supplement the precursors of the Revolution, the seventeenth-century Cossack and peasant revolt led by Razin seemed suitable. It had several advantages. Razin's biography was known sketchily by most Russians. There were songs, dramatic games, poems, and tales about the robber; in fact, the first Russian movie production (1908) was about Razin. Certain symbols were universally familiar: the long boat and the Volga river, which represented the brigand community and its freedom-loving ways, and the captive princess who captured Razin's heart and almost lured him from his comrades.

This brigand already had a history as a revolutionary icon. Socialists had tried to adopt him, but his spirit was probably closer to anarchism. Mikhail Bakunin (Marx's rival in the First International) had seen Razin's uprising as a prototype of his own rebellion: unfettered, rising from the depths of the people, destructive, perhaps also aimless.[22] The anarchistic sailors of Kronstadt even used a song from the popular Razin lore, with new words, as their battle cry in 1917:

From the island-fortress Kronstadt,

To the expanses of the Neva,

A fleet of vessels sails outward—

The Bolsheviks sit at their prow.[23]

Bolsheviks had further reasons for using the Razin legend. Marxist tradition held the peasantry in low regard, but the Bolsheviks found themselves ruling a predominantly peasant nation and maintaining an uncomfortable alliance with the countryside. An attempt was made to absorb the Cossack rebellions that had shaken the old order into the genealogy of the Bolsheviks (who had, after all, done the same). Lenin made the connection nicely on May Day 1919, speaking from Lobnoe Mesto—the site of Razin's execution—at the dedication of his monument: "This monument represents one of the representatives of the rebellious peasantry. Here he laid his head down in the struggle for freedom. Russian revolutionaries made many such sacrifices in the struggle with capital. The best of the proletariat and peasantry perished,

fighters for freedom, but not the sort of freedom proposed by capital, a freedom with banks, with private factories, with speculation."[24]

Razin was prominent in the November 7, 1918, celebration even though the lore, which embodied the peculiarly Russian notion of freedom (volia ) that cherished unfettered will, was scarcely the stuff of Bolshevism. Nevertheless, party propagandists and sympathizers used Razin to represent the revolution's utopian aims: freedom, equality, brotherly love.

Not all versions of the Razin legend were necessarily like Lenin's: artists had their own interpretations. Kuznetsov did a large panel for the Maly Theater in Moscow under the curious title Stepan Razin on the River Beats Back the Advance of Counterrevolution .[25] Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin's panel on Petrograd's Theater Square, Stepan Razin, showed a benign soul, tall and erect—less a Cossack than a peasant Christ with his disciples.[26]

Perhaps the most curious and compelling Razin—one antithetical to Lenin's—was found in a verse play by the futurist poet Vasily Kamensky, Stenka Razin —Heart of the People .[27] Kamensky's image of Razin, which he had created long before the Revolution,[28] was the truncated Razin who would remain popular throughout the war: an elemental force dedicated to the good of the people; a "revolutionary before the proper time" to quote Lunacharsky's paraphrase of Hegel. Razin was naturally destructive, but destructive in a good way, breaking down social obstructions that should not have been there in the first place. It was an optimistic image patched together from a range of sources. Folk songs were a strong influence; futurism, in the rural variety peculiar to Russia, was felt in the "transrational" exclamations; the martial camaraderie celebrated by Denis Davydov returned to Russian poetry after a century's absence; and also present was an ideal of social harmony that appealed to socialists and symbolists alike:

There'll come the day—and the gates will open

Each—for free guests

So that in life any trouble

Will be equal for every venture.

There'll come the day—and forever friends

Will spin roundabout in a choral circle

The poor man—and merchants—and princes.[29]

This was Razin as Rousseau might have liked him, a utopian Razin. There was in fact a strong utopian element to the folk legends of brig-

andry: after the nobility were burned out of their manor houses, a more just popular order would reign in the countryside.

Russian popular culture had in general a rich vein of utopianism,[30] yet with notable exceptions, the utopian visions present in 1918 festivals were drawn from other sources. Foremost was Christianity, which Blok and Mayakovsky used so effectively: the Revolution in Russia was analogous to the advent of Christ. Lunacharsky had given this imagery a broad sanction. In his Religion and Socialism,[31] he reiterated the by-then traditional claim of socialism to the spiritual heritage of Athens and early Christianity. Revolutionary culture took over Christianity's language of exaltation and spiritual ascent. Old symbols were placed in a new cultural context (revolution) that gave them new meaning. In 1918 a decorative panel on the Moscow headquarters of Narkompros depicted a worker and peasant in a style familiar from icons of Cyril and Methodius, the Byzantine missionaries to Slavdom; Petrov-Vodkin's 1918 in Petrograd (1920) depicted a simple Russian girl standing against the background of Petrograd with her child in her arms as a Madonna and Child.[32]

Christianity was not the only source of a utopian vision. In Vladimir Kirillov's "May Day Hymn" (1918)—the first occasional verse for a Soviet holiday—the language of popular liberation merged with the May celebration's pagan roots (perhaps Rousseau would have been pleased).

Glorify May Day in all of its greatness,

The holiday of Labor and the dropping of chains.

Glorify May Day in all of its greatness.

The holiday of freedom, and flowers and spring.

Sisters get into your wedding dresses,

Cover the pathways with garlands of rose,

Brothers, open your arms to another's embraces.

The years of our suffering and tears are all gone.[33]

It sometimes seemed that symbols and the traditions attached to them exerted a stronger influence on the festival than the festival exerted on the symbols. May Day had always competed with the Orthodox Easter, which fell on April 28 in 1918. Another poem written for the holiday suggests how strong the crossover could be:

Arise, O mighty Russia!

Come down, Crucified, from the cross!

The element of liberty is upon us,

Our chains are smashed forever more![34]

In fact, even the banners (khorugvi ) that bore images of Marx, Engels, and Lenin in the May Day demonstration were a direct borrowing from traditional Easter processions.[35]

Proletkultists most frequently resorted to the utopian symbols of religion. Their Christianity was not always borrowed directly but obliquely through Wagner and the symbolists. Part of the cultural redefinition provoked by the Revolution was that responsibilities that had traditionally belonged to high culture were assumed by new poets and playwrights, of whom the Proletkultists were representative. These responsibilities included speaking to and for the conscience of the nation, giving the epoch historical definition, setting a social agenda—all very abstract tasks, but ones that could not be accomplished fully by popular traditions. The last artists to accept and perform these duties had been symbolists; and when proletarians assumed the responsibility, they leaned on symbolists for experience and an idiom. The Russian artist who wishes to speak for the nation assumes a certain tone of voice and a certain style. In symbolist times the tone was often apocalyptic.

On May Day 1919, the Petrograd Proletkult Studio presented The Legend of the Communard, which eventually ran for over 200 shows. The play was written by Petr Kozlov, a peasant soldier who presented himself as a samouchka, or self-taught artist. Before the Revolution, Kozlov had written a decadent-symbolist mystery entitled Above Life .[36] Clearly, Kozlov's self-education had included some Wagner; in a scornful review, Viktor Shklovsky called Legend "Wagner without the music" ("Vagner, vospriniatyi po libretto ").[37]

In the first scene the Communard, whose coming has been prophesied by a Wise Man (arrayed in astrological emblems), is created; his birth occurs in a dark Wagnerian forest.[38] Bent over a fire, the Son of the Sun and the Son of the Earth (the latter is dressed, like Tarzan, in a leopard skin) forge the Communard's heart, which springs to life at sunrise. Meanwhile various evil things, including a Vampire, lurk in the shadows and gnash their teeth. The Communard reflects a familiar ideal: he is "a strong, handsome young man. In him are combined all the elements of the earth: wisdom, happiness, thought, earth, and sun. Long, curly black hair. His face reflects energy and will power, combining kindness and goodness. He is almost naked; only a belt with a symbolic hammer and sickle encircles his waist."[39] Sundry prophesies accompany the Communard's birth; and as he ventures into the world, the Wise Man presents him with a symbolic ring. In an abrupt and inexplicable shift, the second scene opens on a factory floor, where the

proletariat is suffering and exploited. Manifold complaints, however, have not led to any rebellion; that initiative is left to the Communard, who appears to the workers in an upper window. Curiously, in this near-naked youth with the flowing black hair, the workers recognize someone "dressed just like us."[40]

The Revolution had brought egalité and fraternité; naturally leaders and followers would resemble one another. But "the Marxist's communism is not at all the same as the communism of a hick straight from the farm," as Mgebrov noted.[41] If a Russian worker could see himself reflected in long curly hair and a leopard skin, the mirror was less Bolshevik ideology than popular culture. There was, as one critic put it, a "petty bourgeois—peasant [!] element" in the culture, which expected revolution to arrive with a Savior: someone extraordinary, above the common crowd.[42] Religion offered a paradigm for such a historical event.

If the heroic and utopian traditions were Christian, symbols of struggle could also be drawn from the Covenant and Exodus. The fourth and final scene (there is no third scene) takes place in "a gloomy ravine. All around—rocks and the outcroppings of cliffs."[43] The resemblance to the Sinai was not accidental. The people have been liberated from the factory floor and led into the desert toward the Land of Freedom, but the hardships of the trek have disheartened them. A rebellion challenges the workers' leaders; they are accused, like Moses, of leading the people from well-fed slavery to the sure death of freedom. As the rebellion reaches a climax, the Communard again appears to the people and convinces them to continue their journey. They take only a few more steps when their new city—the socialist utopia—appears on the horizon. The play ends (like Mystery-Bouffe ) with a Dance of Labor, performed in harmonic plastic movements: reaping grain, mowing hay, striking an anvil.

Meaning as Power

Artists could find icons of the Revolution in the past. Razin could become a Bolshevik, Christ a socialist. Borrowing and revamping old symbols were essential for establishing a new culture. The process has been given considerable and illuminating attention by historians of the French Revolution, who have gauged popular atti-

tudes by the changing face of political icons such as Marianne, the female embodiment of France, and Hercules, the popular battler.[44] One aspect of the process has, I believe, been neglected: symbols are an instrument as well as a reflector of struggle. At any moment a symbol has a number of potential meanings; and which meaning a symbol gets is often a matter of political struggle. Symbols do not simply acquire meaning; meaning is given. It is not enough to assert that a political power expresses and defines itself with the historical figures it honors.[45] More emphasis should be put on how history is honored; power expresses itself not in how it defines itself by history but in how it redefines history according to itself. Memory is active and selective; it emphasizes what serves its purposes, rejects what does not. A sign and prerogative of political power is the cooptation of history; and an essential exercise in power is to establish oneself as a focus or center, a set of standards and symbols around which history must be arranged.

Early in 1918 the Bolsheviks, insecure in their power, attempted to create and disseminate their own version of the past with a government-sponsored "competition to produce designs of monuments intended to signalize the great days of the Russian Socialist Revolution."[46] Since only six months had passed since those "great days," such an attitude was hardly appropriate, and the plan might have been dismissed outright had it not originated at the top: Lenin had suggested it to Lunacharsky, who in his own words was "stunned and dazzled by the proposition. It was extraordinarily to my liking, and we set to its realization immediately."[47] Included were three undertakings: the removal of monuments raised to the tsars and their "servants"; the renaming of streets and squares; the creation of monuments to the forerunners and heroes of socialism. These three tasks suggested a strategy for creating a new culture. Tearing down the monuments of the old regime would remove its symbols from the Soviet city. Still, all of the national past could not be forgotten or jettisoned. Before a new culture could be created, the remaining elements of the old had to be redefined. In 1918 the monument plan was, for the most part, an effort to grapple with the past: new names were given to old symbols; monuments and symbols that could not be renamed were placed in a new context.

Quick progress was made on the first undertaking: work begun under the Provisional Government on the removal of tsarist emblems from public buildings was continued, and a monument to General Mikhail Skobelev was pulled down as part of the May Day festivities in Moscow. That autumn, monuments to Alexander II and Alexander III

were also removed.[48] The constructive side of the project was not so quickly commenced. By August 1918 a long list of monuments had been drawn up,[49] and a most interesting list it was; not only were socialists such as Robert Owen, Jérôme Blanqui,[50] Marx, and Engels included, but historical "revolutionaries" such as Brutus, Razin, and another Cossack rebel, Ivan Bolotnikov, were honored. Most intriguing was the list of "cultural figures," an eclectic group: writers of socialist sympathies such as Verhaeren found themselves side by side with the likes of Fedor Tiutchev and Rimsky-Korsakov—unlikely champions of socialism.[51] The monument plan reached its apogee on the November 7 holiday with the unveiling of monuments in the center and outlying districts of Moscow and Petrograd. A representative of the party—in some cases Lenin himself—gave a speech at each unveiling, which then developed into a political rally.[52] As the original list presaged, the choice of subjects was eclectic: Marx, Engels, and Robespierre were honored, but so were such nonsocialist cultural figures as the poets Aleksei Koltsov and Ivan Nikitin.[53] Even Dostoevsky was honored, which might have surprised him had he lived to see the Revolution.

Symbols acquire meaning not only through their given properties but through their context. The very fact that a monument had been erected by the revolutionary regime and the subject commemorated suggested a new interpretation: the subject belonged to revolutionary history. For a Brutus or Razin this interpretation was feasible, but when the Bolsheviks claimed the Russian heritage (by honoring Tiutchev, for instance), it was not. To ensure that the desired aspect of each subject was memorialized, the unveiling speech set the tone, and an inscription, chosen from the subject's more progressive statements, was chiseled onto the pedestal. The Chernyshevsky monument, for instance, was graced with the quote: "Create the future, strive for it, work for it, and carry as much of it as you can into the present." The proper interpretation was thus engraved in stone for each viewer.

The monuments, born of symbolic confusion, were often ungainly, and popular understanding resisted the sponsors' interpretations.[54] Some, like the monuments to Robespierre and Volodarsky, were blown up by vandals. Marx himself seems to have suffered most, and that at the hands of his own admirers. One Moscow Marx was, for some reason, gilded; a Moscow statue of Marx and Engels was nicknamed both "Cyril and Methodius" and "the bearded bathers"; a Petrograd Marx, placed before Smolny Institute, was described as "a horrible statue, . . . thick and heavy, standing on a stout pedestal and holding an enormous

top hat like the muzzle of an eighteen-inch gun behind him"; there was even a plan for a "Karl Marx, standing on four elephants."[55] His plight drew embarrassing attention:

Karl Marx has fled the town of Penza.

Actually, it wasn't Marx but his recently erected monument.

Contradictory rumors about the causes of his mysterious disappearance are circulating about the city.

Some say that his horse was seized during the recent mobilization, and Marx refused to continue on foot.

Others . . . claim he went looking for a more appropriate site than Penza. He's decided to tour the cities of the Russian Republic, knowing that every city would be flattered to have such a monument but not every city could afford such a luxury. Marx—the monument—will arrive in some city, stand on the square for several days, and then leave for the next city.[56]

The Lenin plan confronted the old dilemma of how a revolution should celebrate itself by straddling the fence between the permanent and the revolutionary. The two involve contradictory senses of time: the permanent, a sense of eternity in which concrete moments disappear; the revolutionary, a momentary, dynamic present. Lenin seems to have sensed the conflict and suggested naming the plan "monumental propaganda," satisfying both eternal values and the demands of the moment. If this term was not sufficiently unclear, he added, "For the time being I'm not thinking about eternity or even duration."[57] The weather sensed his ambivalence; most of the monuments, cast in gypsum, melted away in the first rain.

Lenin was not alone in his confusion; it represented utopian longings that were strongest when the struggle was fiercest. The idea had a precedent in the revolutionary tradition: Lenin himself mentioned Campanella and his plan to cover the walls of the City of the Sun with edifying frescoes.[58] The plan would also have been familiar to the residents of Utopia, who "put up statues in the market-place of people who've distinguished themselves by outstanding services to the community, partly to commemorate their achievements, and partly to spur on future generations to greater efforts, by reminding them of the glory of their ancestors."[59] A more tangible influence was the efforts of French artists like David (Oath of the Tennis Court ) to memorialize their revolution.[60]

The oddities of the Lenin plan should not eclipse an important point: the Bolsheviks saw festivals as a source of legitimacy. They could rewrite the past to project their presence back onto it, to include themselves in Eliade's cosmic history. Monuments have great power to alter

the structure of time, a task dear to revolutionaries from Robespierre to Lenin. Revolutionaries, in fact, have often used their newfound power to legislate time. One of the Bolsheviks' first legislative acts, passed on January 23 (February 5), 1918, was to switch from the Julian calendar of the Russian Orthodox church to the Gregorian calendar used in the West. Celebrations of the Romanov dynasty were annulled, but as a concession to the religious feelings of the populace ecclesiastical holidays were retained. There were clear political consequences to the calendar changes—church rites no longer had legal authority[61] —yet is also true that the calendar change was long overdue.

A May 12 decree published in Izvestiia introducing a new schedule of holidays was close to the radical legislation of revolutionary France. In the brief life of the French Revolution, profound changes were made in the measurement of space, as were equally profound, albeit temporary, changes in the measurement of time. The first and most controversial change was the conversion to metric measurement; its success is shown by the fact that nobody today remembers that it was first legalized by the Convention. Even fewer remember that this wise decision was followed by the legislation of time in an equally logical manner. The year was divided into twelve months of thirty days each, and the seven-day week of Christianity was replaced by a metric ten days. A new era was declared, its advent being the establishment of the Republic.[62] Bolsheviks, fortunately, were less radical and more generous. The year 1917 remained 1917, and where French workers had exchanged one day off in seven for one in ten, the Russians gained a few holidays: January 1 (New Year's Day), January 22 (Bloody Sunday), March 12 (Overthrow of the Autocracy), March 18 (Paris Commune Day), May 1, and November 7 (the anniversary of the Bolshevik takeover in the new style).[63]

The Bolsheviks also attempted to claim urban space as their own; streets and squares were renamed during the anniversary celebration. Most of the new names were appropriate in a city that had just overthrown the tsar: Palace Square was renamed Uritsky Square after the recently slain Chekist; Nevsky Prospect became the Prospect of October 25; Palace Bridge became Republican Bridge. Not only central points were changed: Big and Little Gentry Streets became the First and Second Streets of the Rural Poor; and Guardian Street became SelfGoverning Street.[64] The plan could be bold and aggressive, as when the Iberian Chapel, one of Russia's most sacred shrines, had a plaque reading "Religion is the opium of the people" attached to it for the November 1918 celebration.[65]

Although the Iberian Chapel plaque was a strong measure, it would

be an overstatement to say that the Bolsheviks, having seized political control, could manipulate symbols at will. Symbols do not always succumb to redefinition; nor can the redefiner assume that the new definition will be accepted. Pilgrims continued to stream into the Iberian Chapel until Stalin leveled it in the 1930s; and unpredictable symbols upset festivals from the very start.

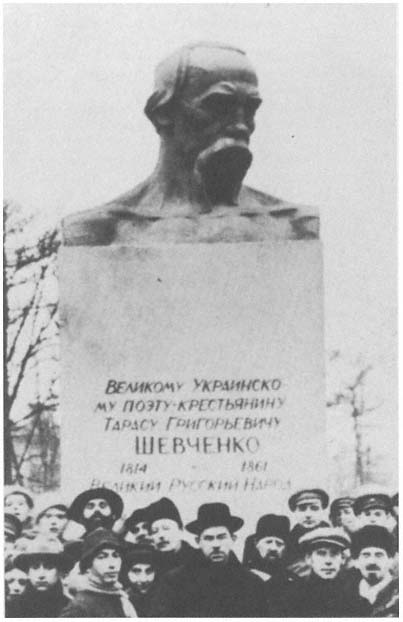

Symbols sometimes gave notice that they were real things, not to be manipulated freely. Airplanes were considered an outstanding emblem of modern science, which Bolsheviks liked to think was on their side. Moscow artists, including Vladimir Tatlin and Kuznetsov, proposed decorating fifteen airplanes, which would perform aerial stunts over Khodynka Field.[66] The intractability of the symbol, however, was discovered in Petrograd, where a plane hired to fly over the celebration crashed in the center of town, killing the pilot and embarrassing the government.[67] Monuments were also unreliable. The dangers of appropriating national or folk heroes into the revolutionary pantheon were made plain at the monument to Taras Shevchenko (see Figure 8), the Ukrainian poet who "with his peasant instinct understood the idea of the Internationale long before its dissemination," when a delegation from the Ukrainian consulate offered a wreath in the name of Hetman Pavel Skoropadsky, head of the nationalist and anti-Bolshevik government.[68]

Perhaps most dangerous in the symbolic game was the outright negation or desecration of an opposing symbol. The Kremlin, which had become the center of Bolshevik power, also had a long history as the symbolic center of the Russian autocracy and Orthodox Church. Iakov Sverdlov ordered the Kremlin commandant to decorate its walls with Soviet symbols and gave him an unlimited budget for the task. On the Troitsky Tower an icon, one of the more sacred of Orthodoxy, was covered by a large panel of a hero in red, flying over the earth.[69] An overwhelmingly religious crowd was offended, and when the panel was blown down by the wind, revealing the icon, rumors of a divine portent spread through Red Square. In the end, the Latvian Riflemen were called in to quell a riot.[70]

May Day 1918: The Struggle for Meaning

The sponsors of most Bolshevik festivals in 1918 saw them as educational events, which would instill in the people the new

Figure 8.

Monument to Taras Shevchenko, Moscow, built as part of Lenin's

monument plan (Mikhail German, ed., Serdtsem slushaia revoliutsiiu.

Iskusstvo pervykh let oktiabria, Leningrad, 1980).

ideology and unite them in the revolutionary cause. In this sense, the Bolsheviks agreed with many modern commentators, who have seen festivals as a prime instrument of socialization into the Soviet system of values.[71] One must beware, however: intention is not execution. Artists commissioned to create festivals often thought differently from their sponsors; symbols, which have histories of their own, were sometimes interpreted differently from the way the makers intended. And, finally, sponsors were not of one mind; as we have seen, there were different opinions and traditions as to how a revolution should be celebrated.

The festive tradition itself was ambiguous, and preparations for the May Day celebration of 1918 sparked conflicts between incompatible notions and hostile factions. To Bolsheviks forged by a decade of political struggle, May Day was a weapon. In prerevolutionary times it was a rare occasion for street gatherings; the demonstrations were actually revolutions in miniature. But another tradition, begun by Wagner, saw festivity as an analog of socialism, a temporary utopia. This abstruse theoretical dispute—what function should a workers' demonstration have when workers control the state—became an acute dilemma with the establishment of a workers' state.

In a pamphlet released for the 1917 observance, Bogdanov wrote, "The May Day holiday is organized to demonstrate . . . that the proletariat is an army of labor in constant battle with capital."[72] Although this goal remained, May Day 1918, coming after the October Revolution, also gave the Russian proletariat reason to celebrate. May Day had been a holiday of struggle against the existing order; and now that workers were the existing order, something would have to change. The holiday could either celebrate what was or continue the struggle for what would be.

Lunacharsky tried to bypass the problem entirely by asking, "But isn't the very idea intoxicating that the state, up 'til now our worst enemy, is now ours and celebrates May Day as its own greatest holiday?" [73] Yet many would have answered with a flat no because the holiday was also a show of power. Before the Revolution, the May Day demonstration had represented the underclass; now it stood for the state, not only as a symbol of power but as power itself. It was a test of the ability to organize the people. Resurgent opposition groups like the Mensheviks, the Special Assembly of Petrograd Factory and Plant Representatives, the Church, and even the anarchists called for a boycott of May Day.[74]

Grigory Zinoviev threatened to "crush the boycott in the most deci-

sive manner,"[75] yet for a celebration with so much at stake, organization was sloppy—a mistake the Bolsheviks would not repeat in the future. By spring 1918, the Revolution was in crisis, and it was only in midApril, two weeks before the event, that the Petrograd party committee headed by Zinoviev decreed that the holiday should be celebrated at all and that the Petrograd Soviet should assume responsibility for the arrangements. The soviet assigned direction of the festival to several groups with little in common. Scholars to this day are not sure who did the actual organizing—and nobody seems to have known in 1918. Reports indicate several possibilities: that the organizers were local labor unions and the Petrograd section of Narkompros; that the soviet took sole responsibility, its efforts directed by a special committee under the leadership of Andreeva; and that celebrations were directed by the Central Organizing Committee, chaired by a certain Antselovich, and the Commission for Decorating the City, both created jointly by the municipal soviet and IZO (the national arts section of Narkompros).[76] The report on this combined effort also states that the groups met in the Smolny Institute and Winter Palace, respectively, which would have made coordination difficult: the two headquarters were located on different sides of a city where communications were notoriously unreliable. Even Proletkult tried to infiltrate and take over the Central Organizing Committee.[77] It is clear enough, though, that organizational lines were not explicit; in fact, the director of the festival's Arts Section, Iakhmanov, ultimately refused all responsibility.[78] Nevertheless, disorganization, a flaw by political standards, allowed for a broad array of styles that makes the festival rich and interesting to our time.

The central newspapers, Pravda and Izvestiia in Moscow and Severnaia Kommuna (Northern Commune ) in Petrograd, were charged with publicity for the event, which they produced in a format that became the subsequent standard. Several days beforehand, official May Day slogans, approved by the municipal party committee, were published, as were march routes, which went through every city district. Pages were filled with recollections of bygone days, when May Day was not celebrated openly. The official papers failed to mention the decorations, as if such efforts were alien to a solemn affair. Should the solemn air, however, have concealed the day's triumphant essence, the April 30 headline of Pravda declared May Day "a workers' holiday, the holiday of the victory of socialism." If it is true that a party in opposition is concerned with the downfall of the old and that a party in confident power is concerned with the construction of the new, then

surely triumph was reflected in the slogans of the day: of eighteen total, fifteen were of the "Long live . . ." variety, while a paltry three proclaimed "Down with. . . ." Obviously, no mention was made of the boycott.

Stylistic multiplicity, political rivalry, poor organization, and Bolshevik ambivalence complicated May Day 1918. The diverse meanings acquired by a single symbol in a single festival—like the panel erected on the Kremlin tower—showed a lack of consensus. Symbols acquire meaning within a context, an interpretative framework: the events they are associated with, the system of ideas they are placed in, the habits of observation that bring some facets into focus and shut others out. The ways that a culture can give meaning to latent signs—at all times dynamic and complex—become terribly tangled in times of revolution. Language itself drifts from its mooring even in a stable culture, and words take on many meanings. Interpretation becomes problematic; one can never be sure that a statement is interpreted according to its design. The act of making a statement assumes that speaker and interpreter can find among many strands of culture a common interpretive framework—and that they wish to.

A competition of contexts can enrich a language and make it flexible in times of change, but if there are too many meanings available, the commonality necessary for communication is lost. The alternative is to assign meaning arbitrarily, by fiat. This is meaning created not by the framework but by the center. For this process to take place, however, there must be a commonly accepted, defining center. On May Day 1918, the Bolsheviks could not even create a unified organization or style, and to speak of a defining center would be premature. They did not yet occupy the central position that permits the creation of meaning: they did not have the power or legitimacy.

To speak of a single meaning in 1918 would be simplistic. It is wiser to find the festival's potential meanings and watch the outcome. The contest for meaning demonstrated how interpretation can be an exercise in power. The Bolsheviks and their opponents, who still controlled party newspapers, had considerable interpretative latitude.[79] Each reporter tried to place the festival in an advantageous context. May Day was, as it had been originally, a day of struggle: to the Bolsheviks, it was a struggle for the new society; to the opposition, against the existing regime. The Bolsheviks called for a demonstration, while opposition leaders called for a counter-demonstration: to the naive observer, both look like a march through the city streets. But when rank-and-file mem-

bers of opposition parties voted to skip the march altogether, the Bolsheviks claimed they were rejecting the counter-demonstration, while the opposition claimed they were avoiding the demonstration. Now, both sides of the debate were faced not with a city of full streets waiting for interpretation, but with empty streets; and at this time the opposition strategically called for a boycott.

The May Day demonstration drew moderate gatherings: although the streets were decorated gaily and filled with marchers, the crowds predicted by the Bolsheviks failed to materialize. Most embarrassing was the absence of workers from the Obukhov and Putilov factories, strongholds of Bolshevik support.[80] Though sheer weariness was a likely cause, people had good reason to honor the boycott. Support for the Bolsheviks was lagging because of failures in the agricultural and industrial economies, the introduction of radical socialist policies, and the Brest Litovsk peace, among other reasons. Nevertheless, there was interpretative latitude. True, the workers did not march in large numbers; and the city was not entirely red. Yet city walls were covered with red banners and posters, and the streets abandoned by workers were filled—mostly by soldiers and by clerks dependent on the Bolsheviks for their jobs.

Given a festival to interpret, the newspapers could provide an acceptable meaning. Izvestiia boasted of the fine weather and defended the workers' right to celebrate—neither of which anyone contested. Pravala admitted some disappointment but drowned the admission in a sea of enthusiasm. Krasnaia gazeta (Red Journal ) took the easy route, adding a zero to some attendance figures.[81] The Bolshevik press called the festival a success; the opposition pointed out that the marchers were soldiers and claimed the Bolsheviks had received no support from the workers. The Bolsheviks said the soldiers were the workers . . . and so on.

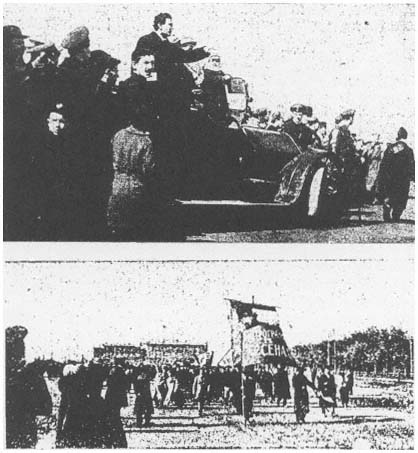

Published pictures illustrate—graphically—how a proper framework could create the proper meaning. Photographers on the Field of Mars, the central congregation point, framed their pictures to show tightly packed crowds around a speaker; but in some pictures a slightly larger frame showed that much of the field was empty.[82] (See Figure 9.) May Day 1918 was the last holiday covered by an independent press; for the anniversary celebration in November, regulations made independent photography virtually impossible.[83]

Although the tradition that recommended mass festivals to the Bolsheviks had a strongly pluralistic element, the dominant characteristic of its underlying cultural model was unanimity. If the Soviet festivals were

Figure 9.

Grigory Zinoviev (top photo, standing in car) addressing the May Day 1918

parade on the Field of Mars, Petrograd. The lower photograph shows the same

celebration from a more revealing angle ( Plamia, 12 May 1918, pp. 8, 9).

to attain the results imagined by their sponsors, conflicting voices would have to be silenced. In this sense, the holiday was a success with those inclined toward the Bolsheviks; they were given an experience of unity and a taste of the culture of the future, while the boycotting opposition gained nothing. The Bolsheviks succeeded in making May Day their own. Herein lies the only possible explanation of Lunacharsky's rather odd—considering the reality of the holiday—recollection eight years hence:

As to the holiday's solemn, unusually piercing and joyful mood, and the beauty of form in which the first May Day after the October Revolution was cast, it was the most successful. I've lived through many a May Day since with the proletariat of Leningrad and Moscow. Each was significant, each was well attended, each was what a proletarian holiday should be, but they were also business, days of accounting, days of self-organization, days of inspection. But not a one so impressed me with its many wonderful pictures, hundreds of thousands of people united by unblighted joy, and the efforts of artists who met the masses with open hearts.[84]

He was remembering either May Day 1918 as others were supposed to or May Day 1917 as it was.

November 1918: The Struggle over Style

The variety of interpretation found in 1918 was also caused by a diversity of styles. The administrators controlling festivals after 1918 were not ambiguous about how the new order should celebrate itself. Friche, who took over in Moscow, preferred displays of harmony and unity along the lines of Rousseau's choral circles; Andreeva, who dominated Petrograd festivals, liked the theme of magnificent endeavor. Neither had a taste for futurism. When Mayakovsky and Meyerhold proposed their anniversary production of Mystery-Bouffe to the Petrograd Theater Section (PTO) headed by Andreeva, she did her best to prevent it.[85]

All parties to the debate over style agreed that artists should devote themselves to the Revolution. The real disagreement was over the nature of the duty and how it should be met. Russian lacks the articles the and a (an ); rarely has grammar made as much difference as it did in November 1918. All concurred with the slogan "Da zdravstvuet revoliutsiia, " but in Russian the phrase can mean two entirely different things: "Long live revolution" or "Long live the [Bolshevik] Revolution." November 1918, the first anniversary of Soviet power, was celebrated under this slogan, and it turned out to be a struggle between the artists' iconoclastic exuberance and the organizers' wish to tame that exuberance.

In Moscow the festival was directed by the Organizing Committee for the October Festivities, established in early October by the municipal soviet. Its work was overseen by a troika of Vadim Podbelsky, Afonin, and Lev Kamenev, who was head of the soviet.[86] Most of the

artwork eventually became the responsibility of the municipal Arts Department,[87] and theaters were administered by Olga Kameneva—head of the Narkompros Theater Section (TEO), wife of Kamenev, and sister of Leon Trotsky.[88]

Although a Narkompros committee consisting of Petrograd's most talented artists, including Blok and Meyerhold, had been meeting since August to plan that city's celebration,[89] a mid-September decree of the municipal soviet placed Andreeva in charge of its Central Organizing Bureau for the October Triumphs. The bureau was given sweeping powers for "the requisition and confiscation of all necessary materials and technical means."[90] Should this seem an idle decree or the festival a trivial matter, it might be noted that the bureau was able to requisition all construction workers from the Petrograd region and, when they did not suffice, additional workers from the Pskov, Novgorod, and Vologda regions.[91] The Central Organizing Bureau returned the favor to those who had granted them such power with a gesture that set an unfortunate precedent: it commissioned hundreds of busts and portraits of Lenin, Zinoviev, Lunacharsky, and other Bolshevik leaders.[92] Because Andreeva had already been appointed head of the Theater and Spectacle Section of the Northern Commune's regional Narkompros,[93] she was given effective control over the entire celebration and did her best to prevent futurist participation.

The Civil War was in full swing by November. The Bolsheviks were engaged in a struggle for life, and the holiday was seen by officials much as May Day had been before the Revolution, as a day of solidarity and struggle. The official mood was best expressed in one of the slogans of the day.

Both crying and singing are useless to dead men:

Pay tribute to them differently.

Step over their corpses without any fear,

And bearing their standard march on.[94]

Andreeva, whose preference for stately celebration was evident in May, spurned the word festival for the more official triumphal celebration, and in a September 25 speech to the Petrograd Soviet called for a solemn affair: "The anniversary celebration will generate the proletariat's confidence in the final triumph of its cause. But while celebrating the anniversary we must not forget that the struggle continues and that our holiday will be of an austere character."[95] And a decree issued by the Moscow Soviet backed official taste with a warning: "In the great days of the

anniversary of the proletarian revolution, an exemplary proletarian order must reign in the Red Capital. Only the strict comradely discipline and self-restraint of the working masses will create such order."[96]

Despite the organizers' austere intentions, the holiday mood was celebratory. On November 7, the second day of the long weekend, Moscow awoke early to the sounds of singing in the streets. Although some might have preferred to sleep late, the sacrifice was rewarded by bolstered rations: two pounds of bread, a half-pound of candy or fruit preserves, two pounds of fresh fish, and a half-pound of creamery butter per person, which were indescribable luxuries in a country on the brink of starvation.[97] Cafés and restaurants were kept open, and food was served without charge; a free dinner was given to the children of Moscow. Similar privileges were extended to the citizens of Petrograd and Saratov,[98] and perhaps other cities.

Lenin's monument plan was in full swing by the November anniversary celebration. Interpretations and reactions to the work attested to the ongoing stylistic debate. Punin's warning against stylistic passivity went unheeded when Dobuzhinsky's treatment of the Petrograd Admiralty met with official approval—despite his recent antipathy to the Bolsheviks. Punin was not alone in objecting to revolutionary monumentalism. Another critic, for instance, feared that "the new revolutionary monuments will be made in the same 'official-domestic' style as the statues to 'the tsars and their servants.'"[99] The alarm was justified. On November 7 an Obelisk to International Revolutionaries was unveiled in Moscow's Aleksandrovsky Garden; the obelisk—a traditional symbol of autocracy—had been erected in 1913 as part of the Romanov dynasty's 300th anniversary celebration, but the two-headed eagle was removed and the names of revolutionaries were carved over those of the tsars.[100]

Avant-gardists insisted that any style that harmonized with the old cities could not be revolutionary. They disdained the coward's evasion—covering statues with red banners—and attacked monuments head on. Often the weapon was humor. In Moscow Annenkov, assigned the distribution of slogans, told how "among the slogans chosen by the Party Central Committee was Marx's well-known, ancient quotation: 'Revolution is the locomotive of history.' In convulsions of laughter, we assigned the slogan to railroad workers and distributed enormous banners, on which a locomotive was drawn with a bearded portrait of Marx on its 'breast' over the cowcatcher."[101]

Theater Square, spread out before the Imperial Bolshoi Theater, was transformed into a field of color; trees were spray-painted in lilac, and

bushes were covered with muslin of the same color. The grass was given a coat of paint through a fire hose.[102] Hunters' Row, an outdoor produce and meat market, was also given a face-lift. Its booths, famous for abundance and variety before the Revolution (and for private trading after), were never known for beauty. A brother-and-sister team, the Alekseevs, covered the booths with bold geometric designs in bright reds, blues, oranges, and purples.[103] A garland of flags stretched over the row between two masts—a traditional decoration for Russian fairgrounds. In the Belorussian town of Vitebsk, house painters scandalized citizens by covering their buildings with the designs of Chagall.[104]

An even more aggressive attack on the old city, and the biggest scandal of all, was raised by Altman's work in Petrograd. Legend claims that futurists used discord inside the Petrograd Central Organizing Bureau to slip their work into the festival.[105] Considering that Altman's work was placed in the city center, that similar work had been hung on Palace Square for May Day, and that it was made of 20,000 arshins (12,000 yards) of bright material,[106] the possibility that it was slipped past anyone is doubtful. More likely, Andreeva, who disliked modern painting, refused to let futurists participate in the festival, and they had their plans approved elsewhere.

Altman's rendering of Palace Square was a mixture of the moderate and the radical; he intended to make its enclosed area suitable for popular festivals.[107] To begin, the autocratic associations had to be removed, which he did by creating a carnival atmosphere. Carnival refutes old meanings by mocking the framework or surroundings that create that meaning. Buildings lining the square were connected with geometrical banners of red, green, and blue. A row of trees on the open side of the square facing the Admiralty was covered with green shields; each carried a few letters that in series spelled "Proletariat of the world—unite!"

Meaning was also attacked and exploded from the center. The center of autocratic Russia was Palace Square, and its center was the most monumental of monuments, the Alexander Column, erected in honor of the European victories of Alexander I. Altman took the ponderous column and translated it into the terms of the surrounding festival; he did a futurist parody. The heavy, three-dimensional masses of the column and its base were fragmented into odd geometrical figures, which came out of the process flat. These figures were arranged in a swirl of fire around the column, which provided an axis that they seemed to spin around. Altman took the muted reds and yellows of the Palace and

General Headquarters and intensified them; the new square was ablaze in orange and red. What had a year and a half previously been the center of an empire became a bright and splashy carnival.

The Reaction

The holiday was enjoyed by many celebrants. The futurist work and its carnival gaiety garnered most of the praise, from various semiofficial papers and from the official organs Pravda and Izvestiia . The official solemnities received little notice; the less official a paper was, the less space it devoted to the "triumphs." As a young member of the Proletkult Literary Studio noted:

What was remarkable was that the "triumphs'" official side—the passing of marching columns, the unveiling of memorial plaques and statues—paled before the universal exultation and immediate feeling of joy. It was majestic, but the majestic took a back seat to carefreeness, solemnity to gaiety. . . . It was not the celebration of an anniversary, the memory of sacrifices, or the ecstasy of a future victory and creative spirit, but the joyful greeting of [the] revolution, the childlike merriment of the great masses' laughter that made the day of [the] Overturn great. . . . The anniversary of the October Revolution became the first day of a new era.[108]

The mood of the day and its peculiar sense of time are captured admirably here.

Articles of the time were in unanimous praise of the festival.[109] Hostile reviews did appear—these are the articles that scholars now quote most often—but they were written long after the fact, in 1919, when criticism of the futurists had gained official backing and was somewhat fashionable.[110] Still, to call the exultation universal was an exaggeration; those antagonistic to the Revolution—a sizeable part of the population—did not share in the celebration and seem to have been rather frightened by the whole affair. As Tamara Karsavina, prima ballerina of the imperial stage, commented, "One was safer indoors."[111]

Oddly enough—and unfortunately since it was a formative event in Soviet artistic policy—many Bolshevik officials agreed with Karsavina. In Petrograd, Andreeva expressed strong disapproval of futurism and claimed the support of the Petrograd proletariat. At a rally of the "working intelligentsia," Andreeva took the podium and read what she claimed were excerpts from the letters of workers incensed by the futur-

ist decorations.[112] Initially, the Petrograd Soviet confirmed its support of the futurists, and the brouhaha quieted down for a few months.

Meanwhile, the battle flared up in Moscow. Modernists were situated in the Moscow branch of IZO Narkompros, a national organization; the aesthetic conservatives (who were often political radicals) were in local soviets. In early February 1919, Lunacharsky decreed that local branches of IZO would be in charge of decorating cities for May Day.[113] Friche, by now director of the Moscow Soviet's Department of People's Festivals, whose control was threatened by Lunacharsky's decree, initiated a long series of antifuturist polemics in the soviet's Vechernie izvestiia (Evening News ), for which he was arts editor. He set a mean-spirited tone in an initial editorial,[114] which was followed by articles by other authors, all under Friche's editorship. The articles, incidentally, inveighed mostly against IZO futurists; Moscow futurists, many of whom worked with the Moscow Soviet's Arts Department, do not seem to have bothered the authors. Kameneva, a vocal advocate of futurists before November 1918, when they worked under her in TEO Narkompros,[115] joined the antifuturist campaign in February, when she was organizing a festival for the Moscow Soviet,[116] and Andreeva initiated antifuturist polemics in Petrograd through her editorship of Zhizn' iskusstva (The Life of Art ).

Friche and Andreeva soon found official support. Friche turned to the soviet, which, after the IZO commission had published its May Day plans, met and decreed that the festivities should be conducted under "the direct control of the Moscow proletariat"—that is, Friche's department. The department vowed to pursue a policy of "neutrality" in matters of artistic taste, at the same time stating that "foolish, tasteless, and antirevolutionary artistic manifestations should not be sanctioned by soviet authority or waste the people's money."[117] In other words, anything but futurism was acceptable. At the same time Andreeva, who stayed in close touch with Lenin, discovered that he was equally displeased: he thought the monuments "outright mockery and distortion" and was particularly miffed when the paint did not come off the trees on Theater Square.[118] Andreeva sent Lenin what amounted to a denunciation of the futurists and, for good measure, blamed her rivals in TEO, Kameneva and Olga Menzhinskaia, who could hardly have been at fault.[119]

By late February, antifuturist sentiment was running strong. When Petrograd painters when to Moscow on the 23rd to help with decora-

tions for the Day of Red Gifts (to front-line soldiers), they were criticized for being alien to the workers; Kameneva's letter was the strongest but not the only condemnation. Andreeva transported the charge to Petrograd and in an unsigned article described the Petrograd painters in a way that stuck in Soviet criticism: "The driving forces of the Revolution were accumulated by degrees, in the depths of the same way of life that the futurists turned their backs on with disdain. . . . To create a work of art answering the demands of the Revolution, to [make] a revolutionary work of art, can be done only by someone in a position to artistically interpret the Revolution. An absolutely necessary condition for that is a close connection with the authentic life and psychology of the people."[120] This was the same argument anti-Bolshevik commentators had forwarded on May Day 1918;[121] and it smelled strongly of prerevolutionary conservatism.

Andreeva's previous complaint to the Petrograd Soviet had met with no sympathy (she was carrying on a notorious feud with Zinoviev's wife, Lilina).[122] But now that administrative control was at stake, the antagonists rallied together; two months after the Narkompros decree was promulgated, the Petrograd Soviet decreed that "in no circumstances shall the organization of the May Day festival be given into IZO futurist hands" and assigned organization to Andreeva, Antselovich, and Nikolai Tolmachev.[123] The Moscow Soviet soon put Friche and Kameneva in charge of its May Day celebration. Because soviets controlled the only available funds, IZO was shut out of the celebration.[124]

IZO made extensive—and ultimately useless—plans for the May Day 1919 celebration. A commission headed by Altman met on March 7 and decided that the holiday would celebrate international proletariat solidarity, a theme to be emphasized by the decoration of important gathering points in harmony with the surrounding architecture.[125] The futurists forsook the brashness and discord of November 1918. Projects were drawn up for "obelisks, architectural barricades, and arches to be erected in squares, streets, and parks. The themes of these decorations will be: the arch of factory labor, the obelisk of farm work, arches and obelisks for the trade unions, science, art, literature, and arches dedicated to revolutionaries."[126]

These projects were far from the modernist "degeneracy" that had so offended Friche, but too much ink had been spilled for polemics to clear. In an article kicking off the February antifuturist campaign, Friche had blamed the failure of previous festivals on the fact that most were

organized in a mere week's time.[127] The bureaucratic scramble preceding the May Day 1919 festival, alas, had the same result: plans were not completed until a week before the holiday.

Discussion of the social role of festivals in the Bolshevik Revolution would be helped by information on mass reception. Unfortunately the masses did not write newspaper articles, and the only accounts we have are of suspect impartiality. The Russian intelligentsia's timeworn tradition of using the people as a rhetorical fig leaf for partisan opinion was continued after the Revolution. Officials steeped in the nineteenth-century academic tradition and speaking in the name of an imaginary people subsequently became the bane of innovative Soviet artists, so it would behoove us to examine Andreeva's charges closely.

The legend that futurism was rejected by the masses—a charge repeated by Russian scholars (often understandable for political reasons) and by their Western colleagues (less understandable)—is unsubstantiated. It was certainly possible that the masses did not like futurist work (though I have seen group portraits from November 7, 1918, taken in front of Altman's column). Andreeva's distaste was not feigned, and it probably represented some portion of popular taste. In Saratov (one of the few well-documented provincial cities), officials were mortified by a tribune decorated, after Henri Matisse, with unclothed female figures painted an unrestrained red.

Nevertheless, we cannot simply declare that popular audiences disliked modernism, whether or not we sympathize. Common Russians, after all, did not share the intelligentsia's prejudice—that art must depict something. Folk art itself was often nondepictive (for example, the applied arts); the simplified and stylized futurism most common on November 7 was familiar to the people from lubki (woodcut illustrations); and abstract work like that of the Alekseevs fit in with popular traditions of carnival decoration. Most of the Russian intelligentsia in 1918 was unfamiliar with modernism, so that the popular audience was in many ways better prepared to receive futurist work—even if they did not understand it as painters intended.

Few if any of the numerous press accounts of the time are reliable indicators of public reception, and speculation on our part is unwarranted. Nevertheless, there is much to be learned from the stylistic debate of 1919. Although we cannot distill a single meaning from the revolutionary festivals, we can discern many potential interpretations. The dynamics of revolutionary culture are manifest in the ways that

potential meanings were rejected by and others accepted into Bolshevik mythology. Perhaps most important, we can watch the Bolsheviks reacting to a society that did not always act as expected. Revolutionary Russia was filled with diverse nations, classes, and factions whose divisions did not always mirror the formulas of Marxist ideology. Commentators of most every stripe agreed on one thing: each felt free to describe the voice of the people as if there could be only one. That notion, shared by Wagner and Ivanov as well as the Bolsheviks, was just one of the authoritarian seeds latent in revolutionary festivals that would bear fruit within a decade.

Official reaction shows how difficult it was for Bolsheviks (and not the Bolsheviks alone) to deal with dissenting views. They saw subversion in stylistic unorthodoxy and division in diversity. Their trepidation was fully manifest in the banishment of futurists, whose unorthodox art actually expressed revolutionary fervor. In his Ode to Revolution, written for the 1918 anniversary, Mayakovsky asked:

How else will you turn out, you of two faces?

A well-balanced building,

Or a heap of rubble?

Judging by their reaction, the Bolsheviks were not sure which he preferred. Their anger at futurists resembled the fulminations of clerics ancient and modern against the license of carnival: both saw beliefs and rules they cherished mocked and defied, and both meant to put an end to it.

Perhaps disapproving officials saw in the futurist decorations an unwelcome hint of anarchy. The year 1918 had seen acute conflicts between the anarchists and the state apparatus; by November they were over but not forgotten. What to the futurists was displacement was to disapproving Bolsheviks anarchy. Alexei Tolstoy, a novelist who never hesitated to inform his readers of the mood in official circles, made the identification of futurism and anarchism explicit in his Road to Calvary:

Moscow under the black [anarchist] flag! We are going to celebrate our victory—do you know how? We'll announce a universal carnival, set up winebooths in the streets and let military bands play in the squares. A million and a half men and women all masked. There's not the least doubt that half of them will come stark naked. . . . We will put up hoardings to the full height of the houses along the streets and paint them with architectural subjects of a new style never seen before. We are going to repaint the trees—we consider natural foliage impermissible.[128]

Yet revolution was the message in 1918, and futurism told it well. This, at least, was the impression that German prisoners of war quartered in Moscow got from the celebration. On Sunday, the final day of the festival, they stormed their own embassy and raised the red flag on its roof. Revolution had broken out in Germany.