Political Upheaval and the End of the Classical Citizen Image:

Menander and Demosthenes

After the death of Alexander, Athens's political stability was shaken by a seemingly endless series of reversals. For several generations, oligarchic and tyrannical regimes alternated with democratic ones, both moderate and radical, each often lasting no more than a few years.

Nearly every change of government brought with it the exile or return from exile of then main protagonists.[58] It is only natural to suppose that these constant political volte-faces had a destabilizing effect on the general mood and the acceptance of traditional standards of behavior in the democratic state. This insecurity would especially have infected the relationship between the individual and the community, creating an urgent need for a new spiritual orientation independent of political values.

In these circumstances, the traditional image of the Athenian citizen also experienced a kind of crisis. I should like to demonstrate this with two exemplary cases, the statues of the comic poet Menander and the orator Demosthenes, both public honorary monuments for which we can reconstruct reasonably well the original location and the historical circumstances. Both statues are rightly regarded as cornerstones of Early Hellenistic art. I wish to place them here alongside the Late Classical portraits of Sophocles and Aeschines primarily to illustrate once again, by means of the contrast, the peculiarly self-contained nature of the Classical citizen image. The values and desires expressed in these new monuments were not in themselves new, but they could, it seems, find public recognition only in the changed political circumstances. In retrospect, this only confirms the suspicion that the moral standards embodied in the imagery of the Classical citizen were a direct concomitant of the democratic political consciousness.

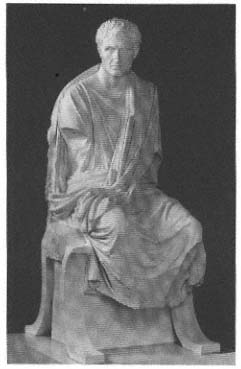

The statue of the comic poet Menander was put up most probably soon after his death in 293/2, in the Theatre of Dionysus in Athens, in a prominent spot at one of the principal entrances. According to the preserved inscription, it was the work of two sons of the renowned Praxiteles, Kephisodotus the Younger and Timarchus. I will pass over the complicated history of the transmission of this portrait type and instead take as my starting point the results of the recent reconstruction by Klaus Fittschen, imaginatively realized with the help of plaster casts (fig. 45).[59] Because, however, the reconstruction still does not give the complete picture (since it is impossible to take account of all the copies at once), a more extensive description will be necessary, to

Fig. 45

Honorific statue of the poet Menander (342–293).

Reconstruction by K. Fittschen with the help of plaster

casts. Göttingen University, Archäologisches Institut.

give an idea of the full state of our evidence as transmitted by the copies.

Everything about this statue runs contrary to the old ideals. The poet, who died at fifty-two, is shown as approximately that age, yet he is seated on a high-backed chair that, on Classical grave stelai, had been reserved for women and elderly men. The seated motif has now taken on an entirely new set of connotations. The poet is presented to us as a private individual who cultivates a relaxed and luxurious way of life.

The chair is a handsome piece of furniture, with delicate ornament. The domestic ambience is underlined by the footstool, slid in at an angle, and the overstuffed cushion that overlaps the sides. Later on we shall see what an important role these cushions play in the iconography of the poet.

Menander sits upright, his garment carefully draped, yet his posture fully relaxed. His legs are positioned comfortably, one forward, the other back, the right arm resting in his lap, and the left descending to the pillow. His shoulders are drawn together, and the head is lowered and, in an involuntary movement, turned to the side. The poet gazes out, as if lost in thought, unaccompanied and unobserved. Why, then, has the artist attached such importance to his handsome appearance and to portraying his calm and idyllic existence? His outfit is also very different from that of earlier portrait statues. The undergarment that he wears would have been considered effeminate in the time of Lycurgus. In addition, the himation is much more voluminous than before, the excess fabric arranged so casually and yet artfully and elegantly as to give the play of folds their full effect. On his feet are handsome sandals with a protective strap over the toes.

The hairstyle, "casually elegant," in the words of Franz Studniczka, betrays a deliberate concern for careful grooming, while the clean-shaven face takes up the fashion introduced by Alexander and the Macedonians, and must be understood as the sign of a soft and luxurious life-style (cf. p. 108).

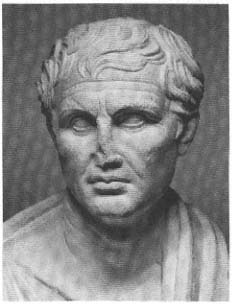

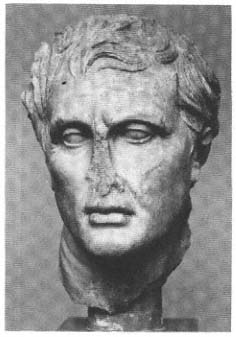

We have already noted how variable the face of Menander is in the different copies. Of the seventy-one copies recently compiled by Fittschen, there is not one that can simply be assumed to be most faithful to the original. It must somehow have conveyed youthful beauty as well as exertion, have been both distanced and introspective. Two busts, in Venice (fig. 46) and Copenhagen (fig. 47), may provide the two poles between which we should imagine the original. The face is, in any event, expressive and personal in an utterly new way.[60] The artist allows the viewer a glimpse into the private realm of the subject. The public and impersonal character of the statue of Sophocles (fig. 25) becomes in retrospect even clearer.

The whole portrait matches rather well what we hear in our sources about the poet's manner and personal style. The most revealing anecdote relates Menander's appearance before Demetrius Poliorcetes, when he hurried to welcome the new ruler. "Reeking of perfume," as Phaedrus writes, he pranced before the new overlord of Athens in long, flowing robes, swiveling his hips, so that the Macedonian at first took him for a pederast, before he heard who he was. But then he too was impressed by Menander's extraordinary beauty (Phaedr. 5. 1). Incidentally the contemporary source from which this quotation must derive specifically mentioned that Menander entered the king's presence with a group of "private individuals" (sequentes otium ), which implies that they were already recognized as a particular segment of society.

The statue of Menander, in its appearance and the way of life it reflects, embodies the very type so repugnant to the radical democrats: the wealthy and elegant connoisseur who withdraws entirely from public life. As is well known, Menander's comedies are essentially apolitical renderings of everyday life. If we can trust later sources, this image seems to be an accurate reflection of his own life. Evidently he did not even live in the city but deliberately withdrew to the Piraeus with his lover, to enjoy a nonconformist way of life.[61] And in this respect Menander was not alone. Earlier on, in the Peripatos, the philosophical school with royalist leanings where Menander studied together with his friend Demetrius of Phaleron, an elegant and luxurious style was highly prized. Even Aristotle was said to have called attention to himself by wearing many rings (Ael. VH 3. 19). When Demetrius of Phaleron ruled Athens as regent of the Macedonian Kassander (317–307 B.C. ), he was accused of leading a decadent life filled with lavish banquets, beautiful courtesans, and expensive racehorses. And it is unimaginable that the extravagant life-style of Demetrius Poliorcetes did not make a deep impression on the Athenians. Surely some of this will have rubbed off on the wealthier Athenians during his long stays in the city. Thus arose the cult of tryphe, a gay joie de vivre associated with this particular circle, a style that would soon become emblematic of the royal image of the Ptolemies in Egypt.[62]

Fig. 46

Bust of Menander. Venice, Seminario Patriarchale. (Cast.)

But the monument to Menander was set up by the Athenian people, at a conspicuous location, and even stood on a tall base that emphasized its official character. If the figure celebrates elements of a particular way of life, we cannot dismiss these as the traits of one famous individual who was looked on as an outsider in Athens. Rather, the oligarchy now in power, installed by Demetrius Poliorcetes, chose to celebrate a way of life that had always been cultivated at the courts of kings and tyrants but was anathema to the democratic polis. Certainly Lycurgan Athens would not have put up a statue to a man like this or at least would never have celebrated in him these particular qualities.

Fig. 47

Augustan copy of the portrait of Menander.

Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

The occasion for the statue was once again, as in the case of Lycurgus' honors for the tragic poets, the great fame and popularity of Menander's work, yet he is not portrayed as a poet. What his friends admired most about him was rather his way of life. Thus Menander's statue can also be seen as a kind of role model, not, however, for a polis oriented toward the ideal of civil egalitarianism, but only for a small segment of wealthy oligarchs and their sympathizers. Or were these now perhaps in the majority?

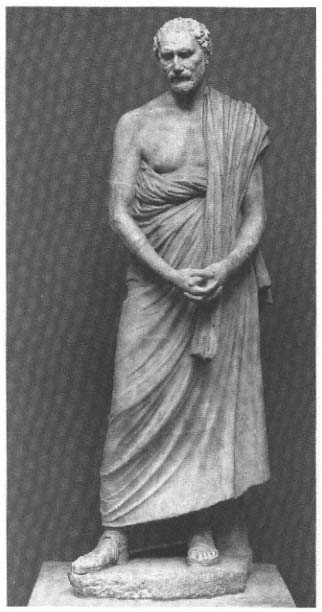

The statue of Demosthenes, by the otherwise unknown sculptor Polyeuktos, put up about a decade later, may be seen as a counterpoint to the Menander portrait, emanating from the camp of the democrats (fig. 48).[63] The simple garment and beard reflect once

Fig. 48

Statue of Demosthenes (ca. 384–322). Roman copy of the

honorific statue set up in 280/79 B.C. (with the hands correctly

restored). Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

again traditional values. But both pose and expression now proclaim for the first time the extraordinary intellectual capacity required for political achievement.

The political situation had once again changed soon after the death of Menander. After 287 the city itself was again free, the old democratic constitution reinstated. Yet there was less room for political maneuvering, so long as a Macedonian garrison remained in the Piraeus. The rehabilitation of Demosthenes, sworn enemy of the Macedonians and defender of freedom, was commissioned by his grandson Demochares, himself a leading democratic politician who had been in exile for seventeen years because he refused to collaborate with the oligarchic regime. The honorific statue of Demosthenes was a clear sign of the renewed Athenian resolve to be independent. The statue's location underlines its political significance. It stood in the middle of the Agora, near the Altar of the Twelve Gods, the famous monument to the goddess Peace, and the statues of Lycurgus and Kallias (Paus. 1.8.2).

Unlike Sophocles and Aeschines, Demosthenes seems to be entirely absorbed in himself. His hands are clasped before him, the head turned to the side, and the gaze directed downward. Despite what looks at first like a quiet pose, the orator is actually shown in a state of extreme mental tension. The brows are almost painfully drawn together, and the position of the arms and legs is not at all relaxed. Everything about the statue is severe and angular, at times even ugly. It has none of the genial quality or self-assured presentation in public of Sophocles or Aeschines (figs. 25, 26). In such a state of concentration, one does not pay attention to the proper fall of the mantle or a graceful posture. Yet Demosthenes' pose cannot be explained simply as a neutral characteristic of the statue's style; rather it expresses a specific message.

As so often in portrait studies, commentators have tried to find biographical clues to the statue's interpretation. The clasped hands are supposed to be a gesture of mourning, to suggest that the failed statesman laments the loss of freedom, a warning to future generations.[64] Yet neither the epigram beneath the statue nor the long accompanying decree gives any hint of failure. The epigram reads: "O Demosthenes, had your power [rhome ] been equal to your foresight [gnome ], then

would the Macedonian Ares never have enslaved the Greeks." The contrast is between gnome and rhome, and Demosthenes is celebrated as a man of determination and insight. Both notions are contained in the word gnome . Since the epigram originated in the circle of the radical democrats, it cannot be taken to imply any criticism of Demosthenes' failure. It merely laments the fact that he did not have access to the necessary military might to implement his political goals.

The statue also celebrates Demosthenes' gnome by rendering the activity in which he won his reputation, as a public speaker.[65] Plutarch reports how excitable Demosthenes became when speaking extemporaneously (as opposed to when he delivered a rehearsed speech). His emotional speaking style was criticized by his opponents as too populist, and Eratosthenes (apud Plutarch) refers contemptuously to the "Bacchic frenzy" in which the orator came before the Assembly. Demetrius of Phaleron is even more specific: "The masses delighted in his lively presentation, while the better class of people found his gestures vulgar and affected" (Plut. Dem. 9.4; see also 11.3).

I believe this passage suggests the correct interpretation of the clasped hands. The statue revives these old accusations of theatrical gestures but refutes them and at the same time praises Demosthenes for his passionate commitment. That is, it asserts, in spite of the extreme effort and concentration of the great patriotic speeches, the speaker never lost his self-control. He grasps his hands firmly before him to show that he has mastered his emotions. Though extremely tense, he does not move his arms, and the mantle remains properly draped. But he is no actor, like his rival Aeschines, who would assume a rehearsed and artificial pose. Rather than showing himself off, he is concerned only with the matter at hand.

The gesture of the clasped hands has, like most others, multiple meanings in Greek art. It can indicate a high emotional state, as Medea before the murder of her children, but also a state of calm and self-control, as on the gravestones. Its specific meaning must be read from the context. I believe my interpretation is confirmed by the occasional reappearance of the clasped hands motif—and an even stronger version in which the two hands grasp each other tightly—on Hellenistic grave stelai, alongside other formulas for depicting a public appear-

Fig. 49

Bust of Demosthenes. Cyrene, Museum.

ance.[66] The gesture can also be found in some later portrait statues that have already been taken to be those of orators, including two torsos of the High Hellenistic period, where it is so dramatically exaggerated as to suggest the "Asiatic" school of rhetoric: the passionate speaker literally wrings his hands.[67]

The "unprecedented pathos" of Demosthenes' facial expression (fig. 49), as Giuliani observes, is indeed to be understood as "a signal for burning political commitment."[68] This is not the expression of a man in mourning. The contracted brows reflect the struggle to find

Fig. 50

Portrait of the general Olympiodorus.

Roman copy of a portrait ca. 280

B.C. Oslo, National Gallery.

the mot juste. We are witnessing here a new paradigm for expressing intellectual activity, one that we shall soon encounter again in the portraits of the Stoics. A comparison with the very different expression of Olympiodorus (fig. 50), in the portrait of this contemporary general who drove the Macedonians from the Mouseion in 287, makes clear that, after the generalized citizen faces of the fourth century, we are now dealing with a new mode of expression that conveys specific talents and situations. Olympiodorus' expression embodies rhome; Demosthenes', gnome .

Alongside the energy and concentration of Demosthenes, his rival Aeschines' appearance—flawless but utterly lacking in emotion—

looks in retrospect rather insincere, mere surface beauty. It is quite conceivable that the statue of Demosthenes was intended as a kind of countermonument to that of Aeschines (fig. 26). Beside the realism of Demosthenes, Aeschines' pose looks rather theatrical, the undergarment and hairstyle effeminate. The portrait of Demosthenes proclaims instead that genuine achievement is gained through extreme effort, that is (and this is the part that is new), intellectual effort. A message of this sort presupposes a very different set of values. The statue's purpose is no longer to present a prescribed model of citizen virtue, but rather to celebrate extraordinary abilities and accomplishments.

With this monument, democratic Athens distances itself from its own earlier ideal of an emotionless kalokagathia . For the first time, an honorific statue of prime political significance celebrates superior intellectual power as the quality of decisive importance. This means, however, that in the representation of Athenian citizens a previously unknown hierarchy becomes apparent. In spite of the many references to earlier tradition, Demosthenes is no longer the exemplary citizen, simply one among equals, like Sophocles and other fourth-century intellectuals. Instead, he is presented as a towering, even heroic figure. Ironically, it was the democratic faction of Demochares that was responsible for this first major break with its own long-cherished image. And this break is but a foretaste of the wholesale shift in values that will reshape the society of the Early Hellenistic age.