Chapter 1—

Flexibility in the Body Social

Mid-sixteenth-century Venice was arrayed in such a way that no single mogul, family, or neighborhood was in a position to monopolize indigenous activity in arts or letters. Venice was a city of dispersal. Laced with waterways, the city took its shape from its natural architecture. The wealthy houses of the large patriciate, scattered throughout the city's many parishes, kept power bases more or less decentralized. Apart from the magnetic force of San Marco — the seat of governmental activities and associated civic ritual — no umbrella structure comparable to that of a princely court brought its people and spaces into a single easily comprehended matrix. As a commercial and maritime city, Venice offered multiplicity in lieu of centralization. It offered rich possibilities for dynamic interchange between the wide assortment of social and professional types that constantly thronged there — patricians, merchants, popolani, tourists, students, seamen, exiles, and diplomats. Local patricians contributed to this decentralization by viewing the whole of the lagoon as common territory rather than developing attachments to particular neighborhoods — a quality in which they differed from nobles of many other Italian towns. Since most extended families owned properties in various parishes and sestieri (the six large sections into which the city still divides), neighborhoods had only a circumscribed role as bases of power and operation; indeed, it was not uncommon for nuclear families to move from one parish to another.[1]

[1] See Dennis Romano, Patricians and "Popolani": The Social Foundations of the Venetian Renaissance State (Baltimore, 1987), pp. 120ff., esp. p. 123; Stanley Chojnacki, "In Search of the Venetian Patriciate: Families and Factions in the Fourteenth Century," in Renaissance Venice, ed. John R. Hale (London, 1973), pp. 47-90; and Edward Muir and Ronald F. E. Weissman, "Social and Symbolic Places in Renaissance Venice and Florence," in The Power of Place: Bringing Together Geographical and Sociological Imaginations, ed. John A. Agnew and James S. Duncan (Boston, 1989), pp. 81-103, esp. pp. 85 and 87. The great exception was patrician women. Their lives outside the home were basically restricted to their immediate parishes, at least so long as their nuclear families stayed in a single dwelling (see Romano, pp. 131ff.). In this, Venetian practice reflected generalized sixteenth-century attitudes that tended to keep women's social role a domestic one. For a summary of the marriage manuals that defined such a role see Ann Rosalind Jones, The Currency of Eros: Women's Love Lyric in Europe, 1540-1620 (Indianapolis, 1990), pp. 20-28.

We can easily imagine that Venetian salon life profited from the constant circulation of bodies throughout the city, as well as from the correlated factors of metropolitan dispersion and the city's relative freedom from hierarchy. Palaces and other grand dwellings constituted collectively a series of loose social nets, slack enough to comprehend a varied and changeable population. This urban makeup differed from the fixed hierarchy of the court, which pointed (structurally, at least) to a single power center, absolute and invariable, that tried to delimit opportunities for profit and promotion. There, financial entrepreneurialism and social advancement could generally be attempted only within the strict perimeters defined by the prince and the infrastructure that supported him. The lavish festivals, entertainments, and monuments funded by courtly establishments accordingly concentrated, by and large, on the affirmation of princely glory or, at the very least, tended to mirror more directly the monolithic interests of prince and court.[2] Courtly patrons with strong interests in art and literature like Isabella d'Este of Mantua or, later, Vincenzo Gonzaga could infuse great vigor into a court's cultural life, even if the nature of cultural production still tended to be more focused and circumscribed than that of big Italian towns like Venice. With less enthusiastic patrons, like Florence's Cosimo I de' Medici beginning in 1537 (and thus coinciding with the Venetian period I focus on here), centralization and authoritarian control could straitjacket creative production according to the narrowly defined wishes of the ruling elite. In the worst of cases they could suffocate it almost completely.[3]

Structural differences between court and city that made themselves felt in cultural production were thus enmeshed with political ones. In contrast to the courts, the Venetian oligarchy thrived on a broad-based system of rule and, by extension, patronage. Within this system individual inhabitants could achieve success by exploiting the city in the most varied ways — through business, trade, or maritime interests, banking, political offices, academic and artistic activities. Such a pliable setup depended in part on numerous legal mechanisms that, formally at least, safe-guarded equality within the patrician rank.[4] The Venetian nobleman's loyalty was in

[2] Among standard commentaries on this are Lauro Martines, Power and Imagination: City-States in Renaissance Italy (New York, 1979), pp. 218ff., 221, 225, and on the courtly penchant for self-reflecting images, pp. 321ff.; idem, "The Gentleman in Renaissance Italy: Strains of Isolation in the Body Politic," in The Darker Vision of the Renaissance: Beyond the Fields of Reason, ed. Robert S. Kinsman, UCLA Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Contributions, no. 6 (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1974), pp. 77-93; and Robert Finlay, Politics in Renaissance Venice (London, 1980), pp. 40-41.

[3] A single example relevant for present purposes is the patronage of madrigals by Cosimo I in Medicean Florence. Iain Fenlon and James Haar, writing on Cosimo I's effect on madrigalian developments in Florence, propose that the end of republican Florence initiated the degeneration of individual patronage dominated by the family. The Medici restoration, they recall, led to an exodus of painters, sculptors, and musicians from the city (The Italian Madrigal, pp. 85-86).

[4] On Venetian distrust of factionalism see Finlay, Politics in Renaissance Venice, p. 38.

principle to his fellow patricians, rather than to a local prince or foreign royalty, who still commanded the service of many noble courtiers elsewhere. In order to maintain the symmetries of patrician power and an effective system of checks and balances, a large number of magistracies and councils shared the decision-making process, and the vast majority of offices turned over after very brief, often six-month, terms.

This made for a cumbersome, mazelike governmental structure that led many observers to comment wryly on the likeness of topography and statecraft in the city.[5] Yet these same observers often marveled at Venice's success in staying the over-inflated ambitions of potential power-hungry factions or individuals. In the late fifteenth century a complex of attitudes guarding against the perils of self-interest found expression in a series of checks advanced by the ruling group to counter the self-magnifying schemes of several doges — schemes epitomized by the building of triumphal architecture like the Arco Foscari, which verged on representing the doge as divinely ordained.[6] Venice had more than its share of calendrical rituals to militate against the claims of the individual by proclaiming overriding communal values to inhabitants and visitors alike.[7] All of these checks and proclamations were designed to secure an ideal of changeless equilibrium and to foster the spirit of unanimitas, of a single shared will, which informed the republic's official ideology.[8]

The patriciate ventured (if hesitantly) to extend these mechanisms to include some nonpatricians. Despite the inequities and stratification that divided nobles from the next rank of residents on the descending social ladder, the cittadini (and even more from the still lower popolani ), the Venetian aristocracy by tradition and a long-standing formula for republican success had accustomed itself to making certain efforts to appease classes excluded from governmental rule.[9] Though without

[5] For a review of comments on the deliberate and unwieldy quality of Venetian government, see ibid., pp. 37ff.

[6] For an interpretation of this phenomenon see Debra Pincus, The Arco Foscari: The Building of a Triumphal Gateway in Fifteenth-Century Venice (New York, 1976). The success achieved by the mid-sixteenth century in checking the doges' schemes is attested by the English translator of Gasparo Contarini's De magistratibus, Lewes Lewkenor, who showed astonishment that the patriciate reacted as casually to the death of a doge as to the death of any other patrician: "There is in the Cittie of Venice no greater alteration at the death of their Duke, then at the death of any other private Gentleman" (pp. 156-57) — a translation from the work of another foreigner, Donato Giannotti, his Libro della repubblica de'vinitiani, fol. 63', as noted by Edward Muir, Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice (Princeton, 1981), p. 268 n. 53.

[7] See Muir, Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice, esp. pp. 74-78.

[8] On the concept of unanimitas in Venice see Margaret L. King, Venetian Humanism in an Age of Patrician Dominance (Princeton, 1986), pp. 174ff. King's interpretation of the interaction of class, culture, and power in quattrocento Venice would argue that the political power of the ruling patrician elite extended far enough into what she calls "the realm of culture" — by which she means the culture of the "humanist group" — as to control them in a unique way (see pp. 190-91, 251). See also Romano, Patricians and "Popolani," pp. 4-11 and passim, on the emphasis Venetians placed on caritas, and Tomitano's letter cited in the Preface above, n. 3.

[9] On this issue see Finlay, Politics in Renaissance Venice, pp. 45ff., and Romano, Patricians and "Popolani," p. 10. On institutions of charity run by citizens and nobles for popolani see the classic work of Brian Pullan, Rich and Poor in Renaissance Venice: The Social Institutions of a Catholic State to 1620 (Oxford, 1971), and on confraternities generally in the period, Christopher F. Black, Italian Confraternities in the Sixteenth Century (Cambridge, 1989). For a study that tries to debunk emphases on Venetian traditions of charity by stressing patrician corruption and the split between civic ideals and reality see Donald E. Queller, The Venetian Patriciate: Reality versus Myth (Urbana and Chicago, 1986). Queller's view seems to me equally problematic in invoking an alternate "reality" as true, rather than traversing the dialectics of various realities and representations.

power of votes, for example, cittadini could participate in governmental activities through the secretarial offices of the chancelleries. They could ship cargo on state galleys. And they maintained the exclusive right to hold offices in the great lay confraternities, the scuole grandi.[10] By sixteenth-century standards the city's embrace was thus relatively broad, and there was considerable play in its social fabric. While many cittadini, as well as plebeians and foreigners, were doomed to frustration in their search for power and position, others experienced considerable social and economic success. At the very least many had come to view their circumstances as malleable, there to be negotiated with the right manoeuvres.

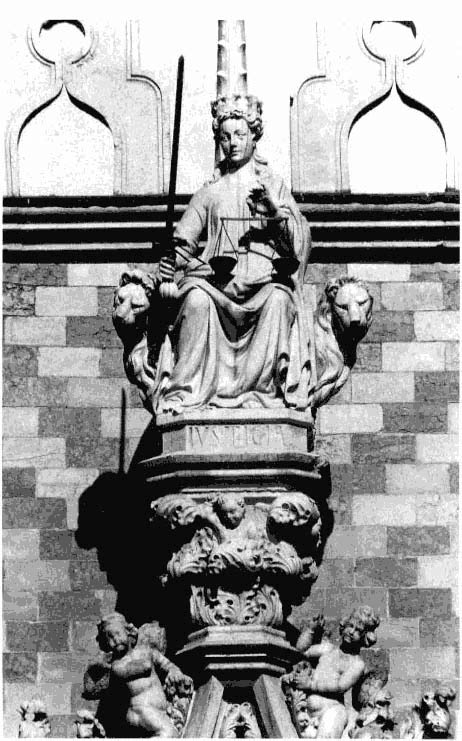

The collective self-identity that promoted various attitudes of equality and magnanimity both within and without the patriciate was expressed with considerable fanfare in official postures. Gradually, the underlying ideals had come to be projected in numerous iconic variations on the city's evolving civic mythology. By the fourteenth century, for instance, Venice added to its mythological symbolism the specter of Dea Roma as Justice, seated on a throne of lions and bearing sword and scales in her two hands (Plate 4). By such a ploy the city extended its claim as the new Rome while reminding onlookers of its professed fairness, its balanced constitution, and its domestic harmony.[11]

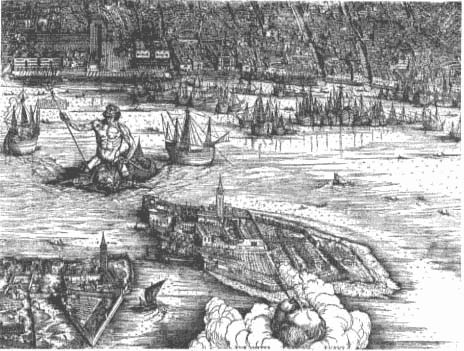

This conjunction of morality and might was reiterated in a series of bird's-eye maps, the most remarkable of which was Jacopo de' Barbari's famous woodcut of 1500 (Plate 5).[12] Barbari's map surrounded the city with eight extravagant personifications of the winds inspired by Vetruvius's wind heads. Set at the extremities of its central vertical axis are powerful representations of Mercury atop a cloud and Neptune riding a spirited dolphin (Plate 6) — iconography as vital to the city's image as its serpentine slews of buildings and its urban backwaters.

Venice's geography played a real part in encouraging the city's social elasticity. The circuitous structure of the lagoon made for a constant rubbing of elbows between different classes that Venetians seemed to take as a natural part of daily affairs. When the eccentric English traveler Thomas Coryat visited the city in the

[10] See Finlay, Politics in Renaissance Venice, pp. 45ff. On the role of the cittadini as members of the secretarial class see Oliver Logan, Culture and Society in Venice, 1470-1790: The Renaissance and Its Heritage (New York, 1972), pp. 26ff.

[11] David Rosand has written on the connections between Venice and ancient Rome in visual iconography; see "Venetia figurata: The Iconography of a Myth," in Interpretazioni veneziane: studi di storia dell'arte in onore di Michelangelo Muraro, ed. David Rosand (Venice, 1984), pp. 177-96. See also Deborah Howard, Jacopo Sansovino: Architecture and Patronage in Renaissance Venice (New Haven, 1975), pp. 2-7. For a single poetic example in which Venice is linked with Justice, see Chap. 4 n. 79 (and Ex. 2) below on Domenico Venier's Gloriosa, felic' alma, Vineggia, as set to music by Baldassare Donato.

[12] See Juergen Schulz, "Jacobo de' Barbari's View of Venice: Map Making, City Views, and Moralized Geography before the Year 1500," Art Bulletin 60, no. 3 (1978): 425-74, and idem, The Printed Plans and Panoramic Views of Venice (1486-1797), Saggi e memorie di storia dell'arte, no. 7 (Venice, 1970). I am grateful to Robert Karrow of the Newberry Library for his help with Venetian cartography.

4.

Bartolomeo Buon, Justice seated with sword and scales, fifteenth century, above the

Porta della Carta, Palazzo Ducale, Venice.

Photo courtesy of Osvaldo Böhm.

5.

Jacopo de' Barbari, woodcut map of Venice, 1500.

Photo courtesy of the Newberry Library.

6.

Jacopo de' Barbari, woodcut map of Venice, 1500, detail, lower middle panel.

Photo courtesy of the Newberry Library.

early seventeenth century, he observed with astonishment that "their Gentleman and greatest Senators, a man with two millions of duckats, will come into their market, and buy their flesh, fish, fruites, and such other things as are necessary for the maintenance of their family."[13] By Coryat's time, of course, Venice's pragmatic patriciate was less able than ever to afford elitist separatism — hence the increasing number of profitable interclass marriages in the sixteenth century, which represented just one type of business arrangement between nobles and cittadini, if one of particular social resonance.

The peculiar habits Coryat observed among the Venetian aristocracy accord with its ideological rejection of showy displays of personal spending (expressly forbidden by strict sumptuary laws) — displays that were de rigueur in court towns like nearby Ferrara and Mantua. Big outlays of cash were supposed to be reserved mainly for public festivals that glorified the Venetian community as a whole. In the private sphere they could be funneled into lasting investments capable of adding to the permanent legacy of an extended family group, but not (in theory) made for more transitory or personal luxuries. Many individual cases of self-glorifying osten-

[13] Coryat's Crudities, 2 vols. (1611; repr., Glasgow, 1905), 1:396-97.

tation naturally reared their heads all the same. But part of their price was a certain dissonance with established mores, which assigned thrift an emphatic place within the official civic scheme. Coryat himself characterized the idiosyncratic shopping habits of the patriciate — and, we might note, with considerable qualms — as "a token indeed of frugality."[14] This was a frugality located within the patriciate's formalized customs for subordinating individual needs to group concerns. It was one ritualized in any number of ways — to cite a single instance, in the conspicuous insistence on modest burials that one finds repeatedly in Counter-Reformational Venetian wills. Both patricians and nonpatricians acknowledged the custom, as evinced by Willaert's quintessentially Venetian request for a burial "con mancho pompa si possa" (with as little pomp as possible).[15]

All of these factors — decentralization, an institutionalized egalitarianism (in policy if often not in practice), and the substantial presence of foreign exiles, travelers, businessmen, diplomats, and military men — contributed to Venice's prolific artistic and intellectual domestic life. Yet the snug sociological picture of divided authority and pluralistic harmony that we might tend to draw from them tells only part of the story. Personal impulses made strange bedfellows with public ideals, and in Venice the latter took their place as only one set of faiths among many others. Venice was above all a paradoxical city. Among the deepest instances of its divided consciousness was that Venetians of the early to mid-sixteenth century who linked themselves to high culture lived in a peculiarly ambivalent counterpose to the court culture from which their city's paradigm was supposed to depart. As a group they prized and flaunted their ideals of freedom, justice, concord, and modesty, while envying much of the apparent exclusivity, homogeneity, and even absolutism that courtly structures seemed to offer.

This tension tempered the civic, rhetorical, social, and aesthetic domains that I aim to draw together here. Let me begin to explore it by turning briefly to the Venetians' manifesto of literary style, Pietro Bembo's Prose della volgar lingua. As I show in Chapter 5, Bembo's Prose advanced a smooth, exclusive diction with the same claims to indisputable authority that tend to characterize aspects of sixteenth-century court production. It translated the harmonious heterogeneity idealized in Venice's oligarchy into the terms of literary style. The temptation to read the Prose as a conflation of courtly values with Venetian civic ones is encouraged by knowledge of Bembo's upbringing and early adulthood. Although he was inculcated with republican ideals, Bembo's youthful experiences with his father, Bernardo, had been tinged with the court. As a boy in 1478-80 he spent time at the Florentine court of Lorenzo de' Medici, which was attended by the Neoplatonic philosopher

[14] Ibid., 1:397. See also Logan, Culture and Society in Venice, pp. 17-18.

[15] The phrase appears in Willaert's will of 26 March 1558, reprinted in Vander Straeten, ed., La musique aux Pays-Bas 6:231, and in the wills of Antonio Zantani and Elena Barozza Zantani (see Appendix, C and D).

Marsilio Ficino and the poet-playwright Angelo Poliziano.[16] His first work of widespread popularity, Gli asolani (1505), was a dialogue set in the tiny, lavish court at Asolo of Caterina Cornaro, ex-queen of Cyprus.[17] In Gli asolani Bembo inscribed the arcane metaphysical philosophies of Ficino that he had encountered years earlier, and something of the Laurentian world that nurtured them, onto a popularized theory of love. This, and Bembo's subsequent sojourn at the court of Urbino, helped authorize him to appear as central spokesman on Neoplatonic love in the courtly manual par excellence, Castiglione's dialogue Il cortegiano, first drafted in 1513-18; by this time Bembo had already written Books 1 and 2 of the Prose, and he completed Book 3 while serving as papal secretary at still another court, that of Pope Leo X.[18]

The intersection of Bembo's biography with Castiglione's text suggests yet another way to consider Venice's codification of courtly values. One of the tropes shared by Il cortegiano and the Prose is that of decorum, which dictates that style should always be modified to suit given occasions and subjects. If their shared commitment to decorum did not lead each author to the same linguistic and lexical norms, with Bembo advocating a formal Tuscan that diverged from the lingua cortegiana favored by Castiglione, it nonetheless points to deeper impulses that form a common substratum between them.

Such impulses are expressed in the persona Castiglione urges on the ideal courtier, a persona rooted in a gestalt that goes beyond the particular form of any momentary rhetorical stance. As Wayne A. Rebhorn has claimed, its essence lies in a perpetual desire to conform to whatever subject or situation is at hand.[19] This driving force demands that one who wears the courtier's mask, like the idealized letterato of Bembo's Prose, invariably display propriety and measured pace. Castiglione elaborates the notion in Book 2, Chap. 7, through an interlocutor who also figures in the dialogues of the Prose, Federico Fregoso: to maintain such conduct the courtier must be circumspect and adaptable, all things to all people. At bottom he

[16] A general account of the elitism of the Laurentian court is given in Gene A. Brucker, Renaissance Florence (New York, 1969), pp. 265-66. For a revisionist view that calls into question the elitism and isolationism traditionally thought to typify Ficino's Florentine circle, see Arthur Field, The Origins of the Platonic Academy of Florence (Princeton, 1988), esp. Chaps. 1, 2, and 7. Field's argument however is mainly relevant to conditions of the Florentine context itself, for it rethinks realities of the Laurentian court, rather than the modes by which outsiders typically idealized it.

[17] On Bembo's time in Asolo and Urbino, see Logan, Culture and Society in Venice, p. 96; Carlo Dionisotti, "Bembo, Pietro," in Dizionario biografico degli italiani 8:133-51; and Giancarlo Mazzacurati, "Pietro Bembo," in Storia della cultura veneta: dal primo quattrocento al concilio di Trenta, ed. Girolamo Arnaldi and Manlio Pastore Stocchi, vol. 3, pt. 2 (Vicenza, 1980), pp. 1-59.

[18] Among recent works that deal with connections between the two see esp. J. R. Woodhouse, Baldesar Castiglione: A Reassessment of "The Courtier" (Edinburgh, 1978), esp. pp. 80-82 and passim; Carlo Ossola, Dal "Cortegiano" al' "Uomo di mondo": storia di un libro e di un modello sociale (Turin, 1987); Giancarlo Mazzacurati, Misure del classicismo rinascimentale (Naples, 1967); Thomas M. Greene, "Il Cortegiano and the Choice of a Game," in Castiglione: The Ideal and the Real in Renaissance Culture, ed. Robert W. Hanning and David Rosand (New Haven, 1983), esp. pp. 14-15; and Louise George Clubb, "Castiglione's Humanistic Art and Renaissance Drama," in ibid., pp. 191-93, 198-201.

[19] See Courtly Performances: Masking and Festivity in Castiglione's "Book of the Courtier" (Detroit, 1978), p. 92 and passim.

is a Stoic — or, in the more skeptical interpretations of Rebhorn, Lauro Martines, and others, an avoider of conflicts and harsh realities.[20] "In everything he does our courtier must be cautious, and he must always act and speak with prudence; and he should not only strive to protect his various attributes and qualities but also make sure that the tenor of his life is such that it corresponds with those qualities. . . . in everything he does he should, as the Stoics maintain is the duty and purpose of the wise man, be inspired by and express all the virtues."[21]

All of this stoical decorum adds up to a well-tended, varied performance, as the continuation of Federico's explanation makes clear: "Therefore the courtier must know how to avail himself of the virtues, and sometimes set one in contrast or opposition with another in order to draw more attention to it" (emphasis mine).[22] The performative quality common to conduct, speech, and literary style, and the flexible social structures it enabled in a city like Venice, will be one of the main themes in my discussion of Venetian verse and music and the salons that nourished them. Style was varied for effect. Federico elaborates the idea in a lengthy analogy between the courtier's mixing of virtues and the painter's chiaroscuro.

This is what a good painter does when by the use of shadow he distinguishes clearly the light on his reliefs, and similarly by the use of light deepens the shadows of plane surfaces and brings different colors together in such a way that each one is brought out more sharply through the contrast; and the placing of figures in opposition to each other assists the painter in his purpose. In the same way, gentleness is most impressive in a man who is a capable and courageous warrior; and just as his boldness is magnified by his modesty, so his modesty is enhanced and more apparent on account of his boldness.[23]

Yet such contrast must be carried off "discreetly" and without obvious "affectation": that is the key to success, since those slight inflections of display will act to entrance the beholder.

Bembo insisted on these qualities for the writer perhaps even more strenuously than Castiglione did for the general courtier. Like Castiglione, Bembo depoliticized

[20] See Rebhorn, "The Nostalgic Courtier," Chap. 3 in Courtly Performances, and (for related points) Martines, "The Gentleman in Renaissance Italy," pp. 77-93. See also numerous essays in Hanning and Rosand, eds., Castiglione, esp. the editors' introduction.

[21] Trans. George Bull, Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier (Harmondsworth, 1967), p. 114. "[È] necessario che 'l nostro cortegiano in ogni sua operazion sia cauto, e ciò che dice o fa sempre accompagni con prudenzia; e non solamente ponga cura d'aver in sé parti e condizioni eccellenti, ma il tenor della vita sua ordini con tal disposizione, che 'l tutta corrisponda a queste parti . . . di sorte che ogni suo atto risulti e sia composto di tutte le virtù, come dicono i Stoici esser officio di chi è savio" (Baldassarre Castiglione, Il libro del cortegiano, ed. Ettore Bonora, 2d ed. [Milan, 1976], p. III).

[22] Trans. Bull, p. 114. "[B]isogna che sappia valersene, e per lo paragone e quasi contrarietà dell'una talor far che l'altra sia più chiaramente conosciuta" (ibid.).

[23] Trans. Bull, p. 114. "[I] boni pittori, i quali con l'ombra fanno apparere e mostrano i lumi de' rilevi, e così col lume profundano l'ombre dei piani e compagnano i colori diversi insieme di modo, che per quella diversità l'uno e l'altro meglio si dimostra, e'l posar delle figure contrario l'una all'altra le aiuta a far quell'officio che è intenzion del pittore. Onde la mansuetudine è molto maravigliosa in un gentilomo il qual sia valente e sforzato nell'arme; e come quella fierezza par maggiore accompagnata dalla modestia, cosi la modestia accresce e più compar per la fierezza" (ibid.).

Ciceronian rhetorical norms in the process, replacing the dynamic involvement with current affairs that inspired Cicero's oratorical model with cerebral ideals of refined detachment.[24] Indeed, it is this role that Castiglione assigned Bembo as interlocutor in Il cortegiano in contriving Bembo's Neoplatonic excursus in the final book, which takes wing just as the work's grounding in social and political reality is all but lost.[25]

Courtly ways were no more excised from the elastic social fabric of Venice than from its literary norms; rather they existed in varying degrees of comfort side by side with indigenous republican ones. The model of the princely establishment even had its analogue in the internal structure of the Venetian government. The doge, although an elected official of the state, had minimal control over policy. He stood in for Venetians as a kind of princely surrogate, divested of real political power but heavily imbued with symbolic force. His principal functions were to guard civic values and to maintain an overarching awareness of public issues. Even the Venetian political historian Gasparo Contarini admitted that the doge's exterior was one of "princely honor, dignitie, and royall appearing shew."[26] This outlook — shared by the Florentine Donato Giannotti — was often taken up and promoted in credulous terms by foreigners, unequipped with any less flattering lens through which to view the figurehead of a powerful state.[27] But it was one created by Venetians themselves, who had vested their doge with both the image of a prince and the power of any garden-variety statesman.

The paradox of the doge remains a telling one. As Edward Muir has written, "in this image one can see the nexus at which many of the tensions in Venetian society

[24] William J. Bouwsma, Venice and the Defense of Republican Liberty: Renaissance Values in the Age of the Counter Reformation (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1968), discusses the tendency in cinquecento Venice toward standardization and fixity in academic matters, relating its presence in Bembo to his lack of interest in contemporary events of historical importance (pp. 135-40). Thomas M. Greene, The Light in Troy: Imitation and Discovery in Renaissance Poetry (New Haven, 1982), similarly links the formal perfection sought by Bembo to a "refusal to respond to contemporary history" (p. 175) and to an effort to avoid the anxieties and political chaos caused by foreign invasions of Italy. Carlo Dionisotti, Geografia e storia della letteratura italiana (Turin, 1967), notes in "Chierici e laici" that Bembo's detachment from political consciousness and service represents a striking break from an earlier Venetian tradition of the scholar-public servant (p. 71). On related questions with respect to a slightly earlier period see Vittore Branca, "Ermolao Barbaro and Late Quattrocento Venetian Humanism," in Hale, ed., Renaissance Venice, pp. 218-43.

Finally, on the Venetian nobility's retreat from the urban realities of commerce, trade, banking, and shipbuilding in the sixteenth century in favor of more idealized existences linked to mainland farming and real estate see Brian Pullan, "The Occupations and Investments of the Venetian Nobility in the Midto Late-Sixteenth Century," in ibid., pp. 379-408; and Ugo Tucci, "The Psychology of the Venetian Merchant in the Sixteenth Century," in ibid., pp. 346-78.

[25] See Martines, "The Gentleman in Renaissance Italy," p. 93, as well as Ossola, Dal "Cortegiano" al' "Uomo di mondo," pp. 34-37. The inherent conflict between Castiglione's monarchism and Bembo's republicanism is taken up by Woodhouse, Baldesar Castiglione, pp. 154-57.

[26] From De magistratibus et republica Venetorum libri quinque (Venice, 1551), p. 43 (trans. Lewes Lewkenor, The Commonwealth and Government of Venice [London, 1599], p. 43); quoted in Muir, Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice, p. 251.

[27] On this aspect of Giannotti and other foreigners see Bouwsma, Venice and the Defense of Republican Liberty, pp. 160-61.

and politics were revealed and resolved."[28] Tensions of this kind centered on the Venetian attitudes toward sensuality and extravagance that I noted earlier. Herein lay another paradox to catch Venetians in an existential bind: despite the much-restricted ideological place assigned to luxuria, the city had more than a healthy share of it in domains outside the strictly communal. This, after all, was the same city that revealed to the artistic world sensuous new realms of color and light and boasted the most beautiful women in Europe. Like its elegant palazzi and gracious waterways, its resistance to invasion, and its invincibility at sea, sensual beauty and luxuriance formed fabled parts of Venetian lore. Many a foreigner commented on the richness and delights to be had in the city, even while remarking on its odd habits of thrift and modesty.

Perhaps most symbolic among its sensual pleasures for the English Coryat and French visitors like Clément Marot and Michel de Montaigne were the great number of courtesans in the city and the unusual abilities cultivated in the upper echelons of the courtesan's trade.[29] "Thou wilt find the Venetian Courtezan," wrote Coryat, "a good Rhetorician and an elegant discourser."[30] By this Coryat had in mind Venice's famed cortigiane oneste, its so-called honest courtesans, women of exceptional grace and high rhetorical polish. As well as being skilled conversationalists and writers, many of these courtesans were singers, often apparently improvising and accompanying themselves on instruments such as the lute or spinet — this in an age that sheltered women closely and kept most nonpatrician women illiterate.

The honest courtesan's success in sixteenth-century Venice thus offers a paradigm for how the city, with its pliable and equivocal social structures, could become an extraordinary resource for inhabitants not born into a full measure of its benefits.[31] For her the city's infatuation with courtliness could be appropriated and manipulated to novel ends, to fashion a reputation that inextricably bound the sexual and the intellectual.[32]

[28] Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice, p. 252, from Chap. 7, "The Paradoxical Prince," the first section of which is headed "The Doge as Primus Inter Pares and as Princeps."

[29] For the writings of Marot, see his letter to the French duchess of Ferrara, Renée de France, Epistre envoyée de Venize à Madame la Duchesse de Ferrare par Clement Marot, in Les epistres: Edition critique, ed. C.A. Mayer (London, 1958), pp. 225-31. Montaigne's observations are recorded in his Journal de voyage en Italie, in Oeuvres complètes, ed. Pléiade ([Paris], 1962), pp. 1183-84. For further on this see Margaret F. Rosenthal, The Honest Courtesan: Veronica Franco, Citizen and Writer in Sixteenth-Century Venice (Chicago, 1992), whose ideas helped stimulate the interpretations I put forth in the following pages.

[30] Coryat's Crudities 1:405.

[31] On the importance of the city for enabling women's speech see esp. Ann Rosalind Jones, "City Women and Their Audiences: Louise Labé and Veronica Franco," in Rewriting the Renaissance: The Discourses of Sexual Difference in Early Modern Europe, ed. Margaret W. Ferguson, Maureen Quilligan, and Nancy J. Vickers (Chicago, 1986), pp. 299-316; and idem, The Currency of Eros, Chap. 5. For an important collection of essays emphasizing the resources offered for the fashioning of identity by the ambiguities and social complexities of early modern city life see Susan Zimmerman and Ronald F. E. Weissman, eds., Urban Life in the Renaissance (Newark, Del., 1989).

[32] In "Surprising Fame: Renaissance Gender Ideologies and Women's Lyric," Jones proposes what she calls a "pre-poetics," an analysis of "conditions necessary for writing at all" in the "ideological climate of the Renaissance" that is apropos here; in The Poetics of Gender, ed. Nancy K. Miller (New York, 1986), pp. 74-95, esp. p. 74.

A few managed to gain fame through the press, plying the arena of public discourse in order to advance their social and economic positions. The most remarkable of these women was Veronica Franco, a cittadina and daughter of a procuress who became a major poet in the 1570s and an intimate of the literary salon of Domenico Venier.[33] In her letters and terze rime she made use of considerable literary aplomb to counter malevolent slander. In one noted instance she parried a detractor by boasting an array of linguistic arms.

Prendete pur de l'armi omai l'eletta. Take your choice of weapons, then.

...................................... ....................................

La spada, che 'n man vostra rade e fora, If you want to use the common Venetian tongue

De la lingua volgar veneziana, As the sword that strikes and pierces in your hand,

S'a voi piace d'usar, piace a me ancora: That suits me equally well;

E, se volete entrar ne la toscana, And if you want to try Tuscan,

Scegliete voi la seria o la burlesca, Choose a lofty or a lowly style,

Ché l'una e l'altra è a me facile e piana. For one and the other are clear and easy for me.

Io ho veduto in lingua selvaghesca I have seen admirable writings of yours

Certa fattura vostra molto bella, In rustic language,

Simile a la maniera pedantesca: And others in a learned vein:

Se voi volete usar o questa o quella. If you want to use either one.

..................................... ...............................

Qual di lor più vi piace, e voi pigliate, Choose whichever suits you best,

Ché di tutte ad un modo io mi contento, I am equally contented with them all,

Avendole perciò tutte imparate.[34] Having learned them all for this purpose.[35]

Franco's bravura served her well in the ambivalent world that cherished the honest courtesan even as it scorned her. As Margaret F. Rosenthal and Ann Rosalind Jones have shown, in speaking out in areas where women had been largely silenced, vaunting her proficiencies in the verbal arts and challenging her defamer in the terms of a male duel, Franco violated a gendered system of rhetorical orthodoxies.[36] Yet in other poems — and herein lies the point — she aligned herself emphatically, if unconventionally, with the rhetoric of the establishment by setting amatory woes alongside patriotic praises of the Serenissima.[37]

Franco was only one of many nonpatricians who ameliorated their marginal social positions by utilizing the city's opportunities for self-promotion and social

[33] On Franco (1546-1591) see most importantly Rosenthal, The Honest Courtesan, as well as idem, "Veronica Franco's Terze Rime: The Venetian Courtesan's Defense," RQ 42 (1989): 227-57.

[34] Gaspara Stampa-Veronica Franco: Rime, ed. Abdelkader Salza (Bari, 1913), no. 16, vv. 109, 112-26 (p. 292).

[35] Trans. adapted from Jones, "City Women and Their Audiences," pp. 312-13.

[36] See also Sara Marie Adler, "Veronica Franco's Petrarchan Terze Rime: Subverting the Master's Plan," Italica 65 (1988): 213-33.

[37] In no. 12 she asks a lover to replace praise of her with praise of Venice (vv. 10-13): "lodar d'Adria il felice almo ricetto, / che, benché sia terreno, ha forma vera / di cielo in terra a Dio cara e diletto" (Praise the blessed and gracious home of the Adriatic, which, though earthly, has the true form of heaven on earth, cherished and precious to God); trans. Jones, "City Women and Their Audiences," p. 315, who dubs this duality a "contradictory rhetoric."

mobility. Another, outstanding for our purposes, was Willaert's student, the organist, composer, and vernacular author Girolamo Parabosco, a Piacentine who arrived in Venice around 1540.[38] Like Franco, Parabosco manoeuvred himself quickly to the center of the Venetian literary establishment. Like her, too, he came from a bourgeois family. In the humble words he professed to Giovanni Andrea dell'Anguillara:

Huomo al mondo son io di poco merto. I'm of little merit to the world,

Lombard Cittadin, non nobile Tosco. A Lombard citizen, not noble Tuscan,

Nudo d'haver, di gran desio coverto. Bare of possessions, and full of wants.

Mi chiamano le genti Parabosco, People call me Parabosco,

E la Musica è mia professione, And music is my profession,

E per lei vita, e libertà conosco. From which I know life and liberty.

......................................... ....................................

Son buon compagno, & un dolor I'm a good chum and only one sorrow

m'accora grieves me:

Di non poter donar non che un Ducato: That I can't deed a single duchy,

Ma un Villagio, e una cittate ancora. Nor even a village, or a city.[40

] Ho sempre un virtuoso amato, I've always loved a man of virtue

Fosse Spagnuol, Tedesco, ò Taliano, Were he Spanish, German, or Italian,

Povero, ricco, o in mediocre stato.[39] Poor, rich, or of middling station.

Not his birth but his virtue makes a man worthy of honor, Parabosco claims, not rank but merit. He himself is no nobleman, not to say Tuscan — that is, linguistic aristocratic — but a mere citizen from modest Lombardy. Later in the same capitolo he alludes to his eminent position in the city as if only to thank those in Venice more highly placed than he.

La festa haver mi potrete à san Marco, During a festival you may find me at San Marco,

Che per gratia de miei Signori Illustri, For thanks to my illustrious signori

Ho ivi di sonar l'organo il carco.[41] I have the duty there of playing the organ.

Parabosco's was no mean duty. In 1551 he became First Organist of San Marco, one of the most enviable posts of its kind in Europe. With this prestigious title, Parabosco held a trump card among literary colleagues in the city's populous salons,

[38] Parabosco was born in 1524 and died in Venice in 1557. For his biography see Giuseppe Bianchini, Girolamo Parabosco: scrittore e organista del secolo XVI, Miscellanea di Storia Veneta, ser. 2, vol. 6 (Venice, 1899), pp. 207-486; and Francesco Bussi, Umanità e arte di Gerolamo Parabosco: madrigalista, organista e poligrafo (Piacenza, 1961). Parabosco's will is preserved in I-Vas, Notarile, Testamenti, notaio Giovanni Battista Monte, b. 706, fol. 230, dated 9 April 1557; a transcription of it appears in Bianchini, pp. 441-42. The will is an ironic reminder of cinquecento disarticulations between the real and the represented: by contrast with Parabosco's satiric projections of libertinism in the Lettere amorose, Lettere famigliari, and elsewhere (see Chap. 3 nn. 16 ff.), his will shows a marked conjugal attentiveness to his spouse, Diana. (Bianchini, not surprisingly, is credulous on this score; see, for example, pp. 225-27.)

[39] La seconda parte delle rime (Venice, 1555), fols. 50-50'.

[40] I am unsure of the precise meaning of this verse and the preceding one. Probably ducato is a pun ("ducat" as well as "duchy").

[41] La seconda parte delle rime, fol. 51.

where music was a valued commodity. His position placed him conveniently betwixt and between — between professional musicians and literati, between nobles and commoners — a situation that made good capital in Venetian society. Elsewhere Parabosco pressed the view that real nobility came from inner worth and not from birthright. His letter to Antonio Bargo of 18 November 1549 affected shock at Bargo's attempt to ingratiate him with an unworthy acquaintance, at his wanting him "to believe that it is a good thing to revere men who live dishonorably, so long as they come from honorable families." Until now he had thought Bargo a person who believed (as he did) that "only virtue may make a man noble, and not from being born in this place rather than that other one, nor from this lineage than another, nor from having much rather than little."[42]

Parabosco answered Bargo in the spirit of familiar vernacular invective that had recently been popularized by Pietro Aretino and followers of his like Anton-francesco Doni. In meting out satiric censure in letters, capitoli, and sonetti risposti, Parabosco engaged in complicated strategies of challenge and riposte, wielding his interlocutors' rhetoric to his own ends.[43] Like Franco, he draped himself at the same time in the cloak of Venetian patriotism. Defending his comedies against certain nameless critics in a letter to Count Alessandro Lambertino, for instance, he shot off a battery of rejoinders, the last of which protested that "some benevolence" should be shown him in the city of Venice, since with all his "study, diligence, and labor . . . [he] had always sought to show the world with what reverence and love [he] regarded, even adored . . . the gentleness, courtesy, prudence, valor, honesty, faith, and piety of these illustrious Venetian men."[44] By presenting himself simultaneously as moral censor and pious celebrant, couching his ire in the terms of a patriot's defense, Parabosco at once created and authorized his new condition as a Venetian. Some years earlier, writing the literary theorist Bernardino Daniello along similar

[42] The complete first part of the letter reads as follows: "M. Antonio amico carissimo, io ho ricevuto la vostra de vinisette del passato, nella qual havete vanamente speso una grandissima fatica, volendomi far credere che sia ben fatto portar riverenza a gli huomini, che dishonoratamente vivono ancora che usciti di honorevole famiglia. se io non credessi che voi lo facesti, perche io cercassi l'amicitia, & benivolenza d'ogniuno: io v'havrei per altro huomo che fin qui non v'ho tenuto. perche fin hora io ho creduto, che voi siate persona che creda, che solamente la virtù faccia l'huomo nobile, & non il nascere piu in questo che quello altro loco, ne piu di questa, che di quell'altra prosapia: ne piu di molto, che di poco havere" (Il primo libro delle lettere famigliari [Venice, 1551], fol. 40). Bargo is almost surely the same as Antonio Barges, a Netherlandish maestro di cappella at the Casa Grande of Venice between at least 1550 and 1555 (when he transferred to Treviso) and a close friend of Parabosco's teacher Willaert.

[43] For a theoretical account of such strategies from an anthropological perspective see Pierre Bourdieu's Outline of a Theory of Practice, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge, 1977), pt. 1, sect. 1, "From the Mechanics of the Model to the Dialectic of Strategies," pp. 3-9, and for a compelling application of Bourdieu to Elizabethan literature see Maureen Quilligan, "Sidney and His Queen," in The Historical Renaissance, ed. Heather Dubrow and Richard Strier (Chicago, 1989), pp. 171-96.

[44] "[M]a s'io non credessi parer prosontuoso, direi bene di meritare almeno qualche benivolenza in questa città. Percioche con ogni mio studio, diligenza, & fatica, cosi in questa mia comedia, come in tutte le mie opere, io ho sempre cercato di mostrare al mondo con quanta riverenza, & con quanto amore, io ammiri; anzi adoro (se ciò mi lice fare) la gentilezza, la cortesia, la prudenza, il valore, l'honestà, la fede, & la pietade di questi Illustrissimi Signori Venetiani; ne mancarò per lo avvenire di pregar il Signor Dio che li feliciti, et renda loro prosperi ogni suo honesto, & santo desiderio: che veramente essi Signori non sono se non pensieri santi, & divini" (Il primo libro delle lettere famigliari, fol. 9'); repr. in Bianchini, Girolamo Parabosco, pp. 352-53. Letter dated 5 August 1550.

lines, he had softened his claim that the elderly were unsuited to engage in amorous pursuits by pleading loyalty to the Venetian gerontocracy. Again his protestations were voiced in the language of Venetian panegyric as it was handed down in civic mythology — or a quasi-satiric inflation of it. Apart from his position on the issue of love, he insisted, he "always spoke of the aged with infinite reverence, especially in this sanctified and blessed Venice, today sole defense of Italy and true dwelling of faith, justice, and clemency, in which there are an infinite number [of old people], any one of whom with his prudence could easily govern the Empire of the whole world."[45]

With these paradoxical rhetorical stances, writers like Franco and Parabosco could avail themselves of transgressive possibilities inherent in the diverse literary genres newly stimulated by Venetian print, yet still align themselves with the prevailing power structure. They were at once iconoclasts and panderers. In both roles they seized the chance to shape their own public images, as Franco told her adversary so unequivocally.

Doni, the plebeian Florentine son of a scissors maker, represented at its most venal the phenomenon of making capital of the social breach. After an unsatisfying start as a monk, he fled Florence for the life of a nomadic man of letters, arriving in Piacenza in 1543 and in Venice the following year.[46] In a letter to Parabosco published in 1544 he derided the ignorance of certain monied patrons on whom the two were forced to depend. "It's true that sometimes I'm ready to knock my head against the wall when I think that the cure for maintaining ourselves has to come from the rich and the amusement in consoling ourselves from the sages; . . . [W]e have virtue and poverty and they infinite nonsense and a great deal of money. But I hearten myself with having as much patience to die as they have the stupidity to live."[47] Doni only spelled out what Parabosco's capitolo to Anguillara had hinted at more furtively, that their wits and wiles would make up for what they lacked in clout and lucre. As if to underscore his irreverent manipulation of printed words and the contradictory strategies that the two of them crafted, Doni's letter then made out as if to return Parabosco's laudatory sonnet with a matching risposta.

Like Parabosco's, Doni's skill at social climbing played a role in Venetian madrigalian developments, if one more mercenary than musical. He possessed a rudi-

[45] "[I]n generale, io parlo sempre con riverenza d'infiniti; che si sa bene, che per tutto, & massimamente in questa santa, & benedetta Vineggia, hoggidì solo schermo d'Italia, et vero albergo di fede, di giustitia, & di clemenza, ce ne sono infiniti, che potrebbono con la lor prudenza, ogn'un di loro governare, & agevolmente l'Imperio di tutto il mondo" (I quattro libri delle lettere amorose, rev. ed. [Venice, 1607], p. 125; see also the Libro primo delle lettere amorose di M. Girolamo Parabosco [Venice, 1573], fol. 61'). The letter, undated, comes from the First Book, which was first printed in 1545 as Lettere amorose. Cf. Venier's stanza set by Donato, Chap. 4 n. 79 below.

[46] For biographical information about Doni, who lived from 1513 until 1574, see Paul F. Grendler, Critics of the Italian World, 1530-1560: Anton Francesco Doni, Nicolò Franco & Ortensio Lando (Madison, 1969), pp. 49-65.

[47] "Vero è che tal volta io sono per dar capo nel muro quando io considero, che il rimedio del man tenerci ha da venir da ricchi, & il trattenimento del consolar ci da i savi. . . . noi abbiamo virtù, & povertà; & essi infinita asineria, & moltitudine di dinari. Ma io rincoro d'haver cosi patientia à morire come gli hanno gagliofferia à vivere" (Lettere [Venice, 1544], fol. ciii').

mentary education in musical composition and described himself in various letters as an amateur composer.[48] Far more important was his role during the 1540s as a chronicler of Venetian music, regularly inserting references to music and musicians into his familiar letters. In addition to Parabosco, he wrote the organist Iaches de Buus, the Piacentine composer Claudio Veggio, one Paolo Ugone, and a singer called Luigi Paoli.[49] Doni asked the last of these to bring his compagnia to his place with their case of viols, a large harpsichord, lutes, flutes, crumhorns, and part books for singing, since they were going to be performing a comedy on the following Thursday.[50] In a letter to Francesco Coccio he jestingly listed musicians who were destined for Paradise — Buus, Willaert, Arcadelt, Francesco da Milano, Costanzo Porta, Giachetto Berchem, and Parabosco.[51] Yet all his attention to music relegated it to the interstices of a project founded in the larger world of Venetian letters.

Doni's eclecticism depended on the city's flexible structures. It leaned away from the elitist, totalizing aesthetic of Bembo toward the grittier, more syncretistic one that the city paradoxically made possible. This is evident in his most famous joining of musical and literary worlds, the Dialogo della musica, published in 1544 by Girolamo Scotto shortly after Doni's arrival in Venice, in which he playfully recreated the casual evenings of an academic assembly.[52] However fanciful (and decidedly popularizing in tone), his Dialogo nonetheless tried to represent the mechanics of exchange in a musical salon that included letterati. As noted by Alfred Einstein and James Haar, the first of the Dialogo' s two parts is unmistakably set in provincial Piacenza, where a circle that formed around the poet Lodovico Domenichi took on the title Accademia Ortolana.[53] The participants in Part I are Michele, possibly a composer and here an alto; a soprano named Oste; the Piacentine poet Bartolomeo Gottifredi called "Bargo," who also sings tenor; and Grullone, a professional musician and bass.[54] Within its fictitious dialogue the interlocutors lightly debate current

[48] For a summary of these see James Haar, "Notes on the Dialogo della musica of Antonfrancesco Doni," Music & Letters 47 (1966): 198-224, to which we may add the following claim — albeit suspect — from Doni's letter generically addressed "A Poeti, & Musici," in Tre libri di lettere del Doni e i termini della lingua toscana (Venice, 1552): "so favellare anche de la Musica" (p. 121); and "io ci ho messo certi Canti ladri, assassinati, stropiati, per farvi dir qualche cosa, & per far conoscere i begli da brutti, & la buona musica dalla cattiva," etc. (pp. 122-23).

[49] Those letters appear as follows: to Buus (undated), Tre libri de lettere, pp. 183-84; to Veggio, dated to April 1544 from Venice, Lettere, pp. cx'-cxi; to Ugone, 9 March 1544 from Venice, Lettere, pp. cv'-cvi; to Paoli, dated 1552 from Noale, Tre libri de lettere, p. 351.

[50] "Voi havete à venire Domenica sera da noi con tutta la vostra compagnia, & portate la Cassa con le Viole, le Stromento grande di penna, i Liuti, Flauti, Storte, & libri per cantare, perche Giovedì si fa la nostra Comedia."

[51] Tre libri di lettere, p. 209. Only Arcadelt and da Milano had no strong known connection with Venice.

[52] Mod. eds. G. Francesco Malipiero and Virginio Fagotto (Vienna, 1964); and Anna Maria Monterosso Vacchelli, L'opera musicale di Antonfrancesco Doni, Istituta e monumenta, ser. 2, vol. 1 (Cremona, 1969). Doni was always fascinated by this sort of academic life. He gives an account of current academies in the last pages of his Seconda libraria (Venice, 1551).

[53] See Haar, "Notes on the Dialogo della musica," pp. 202-5; Einstein, "The Dialogo della Musica of Messer Antonfrancesco Doni," Music & Letters 15 (1934): 244-53; and idem, The Italian Madrigal 1:193-201.

[54] For further on the identities of the interlocutors in Part I see Haar, "Notes on the Dialogo della musica," pp. 203-4, and Einstein, The Italian Madrigal 1:196.

literary issues and chatter about other literati and musicians. In between they freely interpolate sight-readings of music — mainly madrigals.

At the outset the interlocutors decide on the style of their encounters with characteristic self-consciousness. "So that we don't seem as if we just want to rip off or mimic Boccaccio . . . let's sing and tell stories both at once," says Oste, "because where others just say 'Let's sing it again,' 'That's beautiful,' and make similar chitchat, we'll dwell a little more on discussing poetry, making jokes, telling stories [novelle ] and other sweet fantasies [fantasiette ] . . .; and feeding the body that way with a sweet sleep, we'll nourish it with a soft sweetness, or a divine food."[55] Shortly after this they embark on a madrigal of Claudio Veggio's and continue to converse and sing four-part madrigals throughout Part 1.

Once Doni enters the expanded world of Venice in Part 2, new personalities double his resources. Now eight interlocutors are present: Bargo and Michele from Part 1, a woman called Selvaggia, the composers Parabosco and Perissone, Domenichi and Ottavio Landi from Piacenza, and the composer Claudio Veggio, who seems to have been connected with both cities. Pieces handed out from Michele's pouch [carnaiolo ] now accommodate up to all eight of those present. Once again the speakers begin with reflections on their relations to one another and remarks on their use of conventions, all the while laughing at their own bows and curtsies.

SELVAGGIA: Inasmuch as I am among the number of honored women and this music is made out of love for me, I thank you and I am most obliged to Parabosco and everyone.

PARABOSCO: Your Ladyship injures me; for I am your servant.

PERISSONE: Conventional words; are such torrents of theories necessary?

PARABOSCO: Well said. Too much talk in rhetoric.

PERISSONE: I'm just kidding, since you began with servants and such things, which aren't really used by musicians, painters, sculptors, soldiers, and poets.

SELVAGGIA: So that we don't just keep multiplying words, how did you others end yesterday?[56]

[55] "[P]er non parere che vogliamo rubbare o imitare il Boccaccio, se vi governarete a modo mio canteremo e novelleremo a un tempo: perché dove altri si passa cantando asciuttamente col dire solo 'Diciamolo un'altra volta', 'Quest'è bello', e simili chiachiere, noi ci diffonderemo un poco più nel parlare ragionando di poesia, di burle, di novelle e d'altre dolci fantasiette, come più a sesto ci verrà e a proposito; e così cibando il corpo d'un dolce riposo, pasceremo l'animo ancora d'una soave dolcezza, anzi d'un cibo divino" (Dialogo della musica, p. 8).

[56] S. Tanto ch'io son nel numero delle donne onorate e che per mio amore si fa questa musica, io vi ringrazio e v'ho tropp'obbligo e con Parabosco e con tutti.

G. Vostra Signoria mi fa ingiuria; ch'io le son servitore.

P. Parole generali: che bisogna tante scorrentie di teoriche?

G. Dì bene: tanto discorrere su le rettoriche.

P. Dico appunto baie, come tu hai cominciato di servidore e di certe cose, che fra noi non s'usano alla reale da' musici, da' pittori, scultori, da' soldati e da' poeti.

S. Per non moltiplicare in parole, che si terminò ieri da voi altri?

Dialogo della musica, p. 98

At this they move on. Doni continues to aim for the informal realism of a private academy, moving the speakers in and out of their commitment to the discourse and sustaining their self-conscious scrutinies. After the initial gallantries Parabosco announces that their company has been ordered to speak about a beautiful woman by Grullone and Oste. Since neither Grullone nor Oste is there, they sing instead a madrigal about a donna bella set by the obscure Noleth. This prompts a trifling speech by Domenichi on what makes a woman beautiful, in the course of which Doni quotes his own epistolary eulogy of the Piacentine beauty Isabetta Guasca — probably the real-life name of the Dialogo 's Selvaggia.[57] Domenichi will not let up his lengthy disquisitions and as he prepares yet another, Veggio begins restlessly to hum and finally implores the group to sing Parabosco's setting of Petrarch's Nessun visse giamai before letting Domenichi carry on.[58]

In this way Doni presents the salon not only as a dynamic space for arbitrating different styles and tempers but as a vehicle for self-display and self-fashioning. The salon thus functioned like the occasional and intertextual verse of Franco and Parabosco.[59] In a city set up to permit social mobility and obsessed with styling itself according to its wishes, it was natural that by midcentury the growing numbers of private salons should become one of the main marketplaces for the exchange of ideas and artworks. Salons encouraged the sort of juggling for position and exposure common to places of barter. The nobility who formed the salons' main patrons were more receptive to ambitious commoners than they had been before. And by the mid-sixteenth century the means for winning intellectual and artistic recognition within the bustling city had become more diversified and more ample than ever.

Not surprisingly, ambitions proved only more fierce as a result. The ascendency of the private salon following on the heels of Venetian print culture brought quick changes of players, fast renown, rapid dissemination of ideas and artifacts, and above all pressures to excel and adapt quickly to new fashions. The idea of the marketplace, then, is not just metaphorical, for marketplace economies held a material relevance in the city's salons. The salon was not only the concrete locus of patronage, with all that winning patronage entailed; even more crucially, the busy commercial aspect of the city — with its large mercantile patriciate, its steady influx of well-heeled and cultivated visitors, and its thriving presses — increasingly animated

[57] Dialogo della musica, p. 106. On Guasca see Haar, "Notes on the Dialogo della musica, " p. 215, including remarks on Doni's authorship of the piece that follows. Another Piacentine and favorite poet of early madrigalists, Luigi Cassola, addressed her in his Madrigali (Venice, 1544), verso of penultimate folio. For the extensive popular literature containing similar encomia of women see Chap. 3 nn. 39, 41-45 below.

[58] Dialogo della musica, p. 122.

[59] For a standard recent argument on early modern Europe's self-fashioning see the so-called New Historicist position delineated in Stephen Greenblatt, Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare (Chicago, 1980), pp. 1-10 and passim. Prior to Greenblatt's formulation related ideas were developed in text-critical terms by Thomas Greene, "The Flexibility of the Self in Renaissance Literature," in The Disciplines of Criticism: Essays in Literary Theory, Interpretation, and History, ed. Peter Demetz, Thomas Greene, and Lowry Nelson, Jr. (New Haven, 1968), pp. 241-64.

toward midcentury the activity taking place in the living rooms of prosperous Venetians.

The heterogeneity and lack of fixity that typified these salons were interwoven threads in a single social fabric. The very immunity of private groups to concrete description, so confounding to the modern historian, lies at the core of their identity. One of their defining characteristics, this loose organization and openness to change was essential to forming competitive groups. Private gatherings in salons, though often described in contemporary literature as accademie (a term I use here), were in fact only distant predecessors of more formalized academies that proliferated later in the century.[60] Unlike the latter, they made no by-laws or statutes; neither did they invent titles or keep the sorts of membership lists, minutes, and systematic records that were to become commonplace by the end of the century. Instead, they protected their cultural cachet in the safe seclusion of domestic spaces, where discussion, debate, and performance were private. Rather than demanding fixity from either their activities or adherents, they thrived on the easy accommodation and continual intermingling of new ideas and faces.[61] Through most of the sixteenth century, Venetian academies that stressed vernacular arts were almost exclusively of this type. This is true both of academies that concentrated on literary enterprises in the vernacular — poetry, letters, plays, editions, and treatises on popular theories of love and language[62] — and of those musical academies linked to the circle of Willaert. The gatherings of Venetian noblemen like Marcantonio Trivisano and Antonio Zantani or of transplanted Florentines like Neri Capponi and Ruberto Strozzi are all known only from scattered accounts and allusions.[63]

[60] At midcentury such groups mostly went nameless, so that the term accademia, like others they used, was not at first part of a proper name. By reducing them all for convenience to the single epithet academy, I mean to stress their historical relationship to the later groups, but not to confuse their structures with the formalized ones of those later academies. The generic names applied to academic salons during this time were as changeable as their makeups — accademia, ridotto, adunanza, or cenacolo. For further explanation of different meanings of the term accademia see Gino Benzoni, "Aspetti della cultura urbana nella società veneta del'5-'600: le accademie," Archivio veneto 108 (1977): 87-159.

[61] From the growing literature on the academies of Venice and the Veneto, especially notable are Benzoni, "Aspetti della cultura urbana nella società veneta"; idem, "Le accademie," in Storia della cultura veneta: il seicento, ed. Girolamo Arnaldi and Manlio Pastore Stocchi, vol. 4, pt. 1 (Vicenza, 1983), pp. 131-62; idem, "L'accademia: appunti e spunti per un profilo," Ateneo veneto 26 (1988): 37-58. Still informative (if partly outdated), particularly because they incorporate less-fixed academic groups, are the older studies of Michele Battagia, Delle accademie veneziane: dissertazione storica (Venice, 1826), and Michele Maylender, Storia delle accademie d'Italia, 5 vols. (Bologna, 1926-30). See also Achille Olivieri, "L'intellettuale e le accademie fra '500 e '600: Verona e Venezia," Archivio veneto, 5th ser., vol. 130 (1988): 31-56, who explains how academies of the later sixteenth century and beyond came to structure themselves after imaginary collectives in ways that became normative at the time.

[62] For general discussions of informal literary academies in sixteenth-century Venice see Logan, Culture and Society in Venice, pp. 71ff., and, on the fifteenth century, King, Venetian Humanism, pp. 12-18. Outside this pattern are a very few public-minded and philologically oriented academies that grew up earlier in the century; in the early cinquecento this includes the Neacademia of Aldus Manutius, devoted to Greek scholarship, and at midcentury the Accademia Veneziana, also known as the Accademia della Fama, devoted to an encyclopedic agenda of learning and publication. For the Neacademia see Martin Lowry, The World of Aldus Manutius: Business and Scholarship in Renaissance Venice (Ithaca, 1979), pp. 195ff., and on the Accademia Veneziana, Chap. 4 nn. 91ff. below.

In the remainder of Part 1, I try to depict the textures of vernacular patronage in Venice by focusing on the private worlds of figures such as these. Chapter 2 begins with the pair of Florentine exiles Capponi and Strozzi, apparently the main private benefactors of Willaert and Rore, respectively, from about the late 1530s until the mid-1540s. As rich aristocrats and singers of domestic music, they represent a kind of private patronage that shunned the popularizing commodifications made by the likes of Parabosco. They stand in sharp opposition to another foreign patron, Gottardo Occagna, who sponsored prints of vernacular music and letters in Venice from about 1545 to 1561. Fictitious printed letters to Occagna from Parabosco that feigned public displays of private diversions suggest he colluded with vernacular artists in mounting the Venetian social ladder. Central to my assessments of both Occagna and the other protagonist of Chapter 3, the patrician Zantani, are the ways in which social images were fashioned through the rhetoric of Petrarchan love lyrics. The juxtaposition of Occagna's and Zantani's cases shows that while those outside the Venetian patriarchy might invert this rhetoric to mobilize their positions, the local aristocracy sought out ennobling texts and images to reinforce their status claims. Zantani probably promoted some of the many encomia of his wife that were made in the rhetoric of Petrarchan praise, and he engineered several printed volumes that could bring him renown, not least an anthology with four of the madrigals from Willaert's (then) still unpublished Musica nova corpus.

All of these figures are maddeningly elusive to our backward gaze. It is only in Chapter 4, with the salon of another native patrician, Domenico Venier — a friend of vernacular music whose palace was the literary hub of midcentury Venice — that we come to see the full richness of exchange, the gala of personalities, the competitive forces they set in motion, and the fruitful intersection of art and ideas that the flexible social formation of Venice allowed.

[63] Distinctly removed from this mold are several academies on the mainland, most notably the highly organized Accademia Filarmonica of Verona, established at the self-educative initiative of Veronese noblemen — a group that for all its enterprise and interest in fashions on the lagoon lacks the urban nonchalance and elasticity of the Venetians. On academies in the Veneto see Benzoni, "Aspetti della cultura urbana nella società veneta," and Logan, Culture and Society in Venice, pp. 72ff.