Ten

Medicine, Racism, Anti-Semitism:

A Dimension of Enlightenment Culture

Richard H. Popkin

As Europe expanded through the Voyages of Discovery and colonized the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Polynesia, the problem of explaining the varieties of human beings became a focal point. For the most part, explanations for why people differed in skin color, hair, and eyes were offered within a framework based on the Bible. In similar fashion, religious differences were accounted for in terms of the vicissitudes of the human race since the collapse of the Tower of Babel. These differences are twofold: (1) physical, relating to bodily characteristics, and (a) mental or spiritual, relating to the workings of the mind.

As explorers, historians, and geographers studied these varying populations, they became acutely aware of the range of human characteristics. People sought explanations for why we differed so, and various theories were offered about the nature of the human race. A consideration of these theories, particularly as they apply to the physical and mental properties of Jews and Negroes as victims of racism, will be the focus of our attention. I will trace the road from scripturally based color-racism and anti-Semitism to secular versions, with a view toward science rather than revelation. And some may be surprised at the malignant role played by well-known heroes of the Enlightenment, and the benevolent role played by various unenlightened types as well.

According to Scripture, after the Flood, because Ham and Canaan saw Noah naked and drunk and did nothing to cover him, they were cursed. Noah awoke from his drunkennness, we are told, realized what his younger son, Ham, had done to him, "and he said, Cursed be Canaan, a servant or servants shall he be unto his brethren." Many inter-

preters in the seventeenth century offered the view that Noah's curse on Ham and Canaan caused both them and all their descendants to be dark, and servile.

Developments in both the crushing of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews and the exploration by enslavement of the Africans introduced further biological content to explain Jewish and African differences. In fifteenth-century Spain and Portugal, an attempt was made to eliminate religious differences after the reconquest by forcibly converting Jews and Moslems to Christianity. This act produced the only major case of Jewish converts who retained their differences and remained identifiable as Jews. They were labeled "New Christians" and "Marranos" (a slang term for pig), who, though baptized as Christians, were still, in some significant sense, Jewish, and a threat to Christianity. The notorious Spanish Inquisition was introduced to ferret out the Judaizers among the New Christians. This converted group was given a biological definition: someone was a New Christian if he or she had a New Christian or Jewish ancestor in the last five generations. People were Old Christians if they could produce evidence of limpieza de sangre, purity of blood.[1] Somehow, the biological feature of Jewishness became extremely hard to eradicate by usual Christian means of conversion and baptism. Hence, well into the eighteenth century, the Portuguese were keeping records of who was half New Christian, one-quarter, one-eighth, one-sixteenth, and, beyond that, "part" New Christian or Jewish. And, still, the Inquisition insisted that biological Jewishness contained the seeds of spiritual Jewishness that were dangerous to Christianity. Authorities made little progress in defending or delineating the biological features of Jewishness, except in terms of genealogy. The Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions had lists of behavioral manifestations of Judaizing, which included any form of Jewish religious practice, especially not eating pork, not working on Saturday, wearing clean clothing and lighting candles on Friday night, fasting on Yom Kippur, and celebrating the Passover meal. Owning Hebrew books was also a sign of Judaizing, unless one had special permission. However, none of the above would indicate a biological basis of Jewishness. Almost all inquisitional cases are about behavioral practice and genealogy and beliefs.

A further complicating factor is that in some special cases, known

[1] Concerning the New Christians and Marranos, see H. Charles Lea, History of the Inquisition in Spain, 4 vols. (New York, 1907); I. S. Revah, "Les Marranes," Revue des études juives 118 0959/60): 29-77; Cecil Roth, A History of the Marranos (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1907); and A. A. Sicroff, Les controverses des status de pureté de sang en Espagne du XVe au XXIIIe siècle (Paris: Didier, 1960).

Pl. 20. Tide page of.Johann Christoph Wagenseil's Benachrichtigungen wegen einiger die Judenschafft angehenden wichtigen Sachen, Erster Theil … I. Die Hoffnung der Erlösung Israelis ... (Leipzig, 1705).

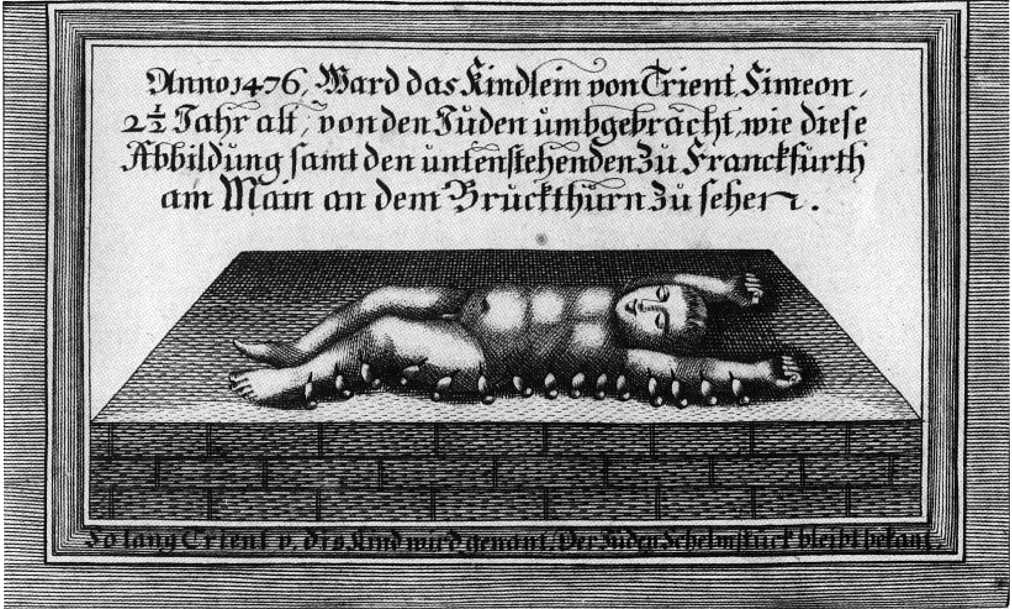

Pl. 21. Illustration of a two-and-a-half-year-old Christian child from Trent being bled with leeches by Frankfurt Jews, from Johann Christoph Wagenseil's Die Hoffnung der Erltsung Israelis (see plate 20).

New Christians were made honorary Old Christians, or their New Christian character was ignored because of their importance in the Christian world. For example, the family of Pablo de Santa Maria, bishop of Burgos, who had been Solomon Halevi, rabbi of Burgos, were declared honorary Old Christians. The Santa Maria family claimed to be descended from the family of Mary, the mother of Jesus, and thus, though Jewish, were traceable to the first family of Christianity.

Santa Teresa of Avila was known to be the daughter of a New Christian who had been found to be secretly Judaizing. Diego Laynez, the second general of the Jesuit order, was known as the Pope's Jew. During his lifetime several of his relatives were punished for secretly practicing Judaism.

This religious and political manipulation indicated that genealogical facts could be ignored when desirable. Cervantes proposed a solution when he had Don Quixote announce he had no ancestors, hence no genealogy.[2] In the case of color discrimination, as blacks became part of the economic world of the whites, people discoursed "upon the Grand Division of mankind into Blacks and Whites. " In one of the most popular and little-used sources (by present-day scholars), Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy at Paris, which appeared in over thirty English editions between 1692 and 1803,[3] the spy told the president of the college of science at Fez that

[2] A work of the time, the Myth of Spanish Nobility, tried to show that all Spanish noble families, including that of Ferdinand of Aragon and Torquemada, had Jewish blood.

[3] The Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy, or L'espion turc (after its first printing), is a most important source of what was being discussed, or taken seriously, from about 1684 to 1800, among the literary public. The work is hardly used by present-day scholars, but was widely published during the Enlightenment. The first two volumes appeared in French (though written in Italian). The next six appeared in English (also an additional one, attributed to Daniel Defoe) and were translated into French, German, Dutch, and even Russian (an edition encouraged by Catherine the Great). There were at least thirty-one English editions, six French, six German, six Dutch, one Italian, and one Russian edition. The work established a genre for discussions critical of, or touching questions about, European ideas; namely having an outsider, the Turkish Spy, make dangerous and/or heretical points. The Petsian Letters, the Chinest Letters, the Jewish Letters, the Cabbalistic Letters, are all sequels to the Turkish Spy's technique. I believe this untapped source will be very important in assessing questions that were being discussed, and answers that were being considered. In some other articles, I am dealing with some specific cases, the view in the Turkish Spy of the pre-Adamite theory, the attempt to reform Judaism in the Turkish Spy, the Turkish Spy as a source about the Messianic movement of Sabbatai Zevi. For information about the Turkish Spy and its many editions and possible authors, see Giovanni P. Marana, Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy, selected and edited by Arthur J. Weitzman (London: Roufledge and Kegan Paul, 1970), Introduction, vii-xix, 232-233; and C. J. Betts, Early Deism in France (The Hague: Nijhoff, 1984), chap. 7.

he had met an eminent physician recently and that together they had inquired

into the Causes of the Differences of Colour; whether it proceeded from the Various Heat and Influence of the Sun, or from the Divers Qualities of the Climates wherein they live; or finally, from some Specifick Properties in themselves, in the Natural Frame and Constitution of their Bodies. He was of Opinion, that if Adam was White, all his Children must be so too; if Black, all his Posterity must be of the same Colour. Therefore, by Consequence, either the Blacks or the Whites are not the Descendants of Adam.[4]

These alternatives covered just about all of the possibilities considered during the eighteenth century.

During the latter part of the seventeenth century, a critique developed against biblical explanation of human phenomena. The work of Isaac La Peyrère, Baruch de Spinoza, Richard Simon, the author of the Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy in Paris, and the early English deists among others, questioned whether we had an accurate text of the Bible and whether the Bible as we know it is an accurate account of human history. La Peyrère's Men before Adam raised the possibility that there were non-Adamic origins of most inhabitants of the earth. The evidence he offered from ancient history and newly discovered cultures, together with his biblical criticism, led to the rise of an intellectual group who sought to explain human differences in natural terms.[5] Spinoza's naturalism, as well as the impact of the Italian Renaissance naturalists, produced attempts to explain the varieties of mankind apart from the Scriptures (and to explain the Scriptures as one small episode in human history). The dominant explanations were in terms of either multiple origins of man (polygenesis) or environmental and cultural influences on an initially common human stock.

La Peyrère's theory that there were men before Adam was offered for scientific and religious reasons to justify a peculiar view about the imminent culmination of Jewish and world history in which everyone, Adamite (that is, Jew), and pre-Adamite (that is, gentile), and post-Adamite would be saved.[6] While theologians ranted against the work,

[4] [G. P. Marana], The Eight Volumes of Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy, Who Liv'd Five and Forty Years, Undiscover'd at Paris (London, 1723), 8:264. This is usually listed as the eighth edition. The text is almost the same in all editions.

[5] On La Peyrère and his influence, see R. H. Popkin, Isaac La Peyrère: His Life, His Works, and His Influence (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1987).

[6] Cf. R. H. Popkin, "The Marrano Theology of Isaac La Peyrère," Studi internazionali di filosofia 5 (1973): 97-126; and Isaac La Peyrère, chap. 3.

and theological authorities had the work burned and banned (and Spinoza and the author of the Turkish Spy offered more evidence for the view),[7] some more practical people saw a wonderful application of the theory in the question of human differences. Planters in the Virginia colonies by the 168os were using "the pre-Adamite whimsey" to justify black slavery.[8] The blacks were of separate and different origin and did not have the intellectual or spiritual properties of whites. Hence, feeling was they should not be Christianized, since they lacked the requisite mental or religious capacities. Further, the physical differences between blacks and whites showed the separate origins of each group. Therefore, an intensive study began to locate and explicate the major differences (and so a branch of physical anthropology was born). Biologists, medical practitioners, explorers, among others, offered their findings concerning the differences, and then began seeking causal explanations either in the original characteristics of different racial stocks or in the transformations that had occurred owing to climate, temperature, diet, and so forth. The explanations almost always started from one of two assumptions, either that blacks began with and have continued to have fundamental defects that make them intellectually and spiritually inferior to whites, or that blacks have developed fundamental defects that make them presendy inferior to whites. The different implications of these two assumptions are enormous in terms of whether the so-called "defects" are remediable or not. Before going into further details, let us first examine the secular versions of why Jews are different from Christian Europeans.

Until the Spanish Inquisition introduced biological criteria to answer "Who is a Jew?" or "Who is a New Christian?" the prevailing Christian view was that people were Jews by choice. They willfully and stubbornly accepted certain views and practices, and hopefully could be brought to choose other views and practices, namely those of Christianity. Among seventeenth-century millenarians, the conversion of the Jews was a most

[7] In the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus Spinoza kept pointing up internal evidence in the Bible that indicated mankind existed before Adam. The Turkish Spy actually offered a more complete list of reasons for taking pre-Adamism seriously than any other work of the time. In fact it offered material about oriental theories of the origins of the world that did not become part of the general European discussions until at least fifty years after its original publication. Some of these data also appear in Charles Gildon's letter to Dr. R. B., in Charles Blount, The Oracles of Reason (London, 1693), 177-183, but does not seem to have been picked up at the time.

[8] See the criticism of this view in Morgan Godwyn, The Negro's and Indians Advocate, Suing for Their Admission into the Church; or, A Persuasive to the Instructing and Baptizing of the Negro's and Indians in Our Plantations (London, 1680), Preface and chap. 1.

critical matter, since it would be the penultimate event before the Second Coming of Jesus and the Commencement of His Thousand-Year Reign on Earth. Millenarians thought that great efforts should be made to prepare for the Conversion but that God alone could and would bring about the great event.[9] When the event occurred, the converted Jews would be spiritually and biologically identical with everyone else. They might even be better spiritually because so much divine effort was invested in their case.[10]

By the end of the seventeenth century, those who no longer saw the Jews as a special group in providential history who would be united with everyone else began to see them as an odd cultural group that was identifiably different from others in Europe by dress, hairstyle, occupation, eating habits, cultural activities, and so forth. For many, these differences could be eradicated by an individual's deciding to join the Christians. There is considerable testimony about Jews who individually decided to convert, who then became accepted members of the society around them, and whose descendants became indistinguishable from the other members of the society.[11] In fact, several prominent noblemen and women in Europe have been startled by genealogical inquiries that show that they are descendants of Jewish converts.[12]

[9] This was the view of Isaac La Peyrère, of Joseph Mede of Cambridge, and of the leading millenarian, John Dury, among others. La Peyrère devoted a good part of his Du Rappel desJuifs ([Paris?], 1643) to advice on how to make Jews ready for conversion; Mede offered the theory that dominated English millennial thinking, that the conversion would occur by miracle as it did in the case of St. Paul. Dury worked on many conversion projects such as establishing a college of Jewish studies in London, publishing editions of Jewish classics like the Mishna, readmitting the Jews to England, but all of these were seen as only preparatory. On this, see my article "Jewish-Christian Relations in Holland and England," in Jewish-Christian Relations in the Seventeenth Century, ed. S. Van den Berg and E. van der Wall (The Hague: Nijhoff, 1987).

[10] La Peyrère suggested this in his Du Rappel des Juifs.

[11] In England, the converts often wrote an account of what led them to see the light. The authors of these, like Moses Marcus in the early eighteenth century, became regular members of society and often advisers on religious matters, or Hebrew teachers. Their descendants merged into the general population both in Europe and in America.

[12] There is an interesting case in the unpublished Cazac papers at the Institut Catholique de Toulouse, when a local archivist, writing on Montaigne's cousin, Francisco Sanches, asked a French nobleman, the Marquis de Saporta, if the family had any papers of their illustrious ancestor, the Chancellor of the University of Montpellier in the sixteenth century, who was a New Christian. The twentieth-century nobleman tried desperately to avoid accepting his heritage until it was pointed out to him that his title came from his Jewish ancestors who were ennobled in the sixteenth century. The twentieth-century marquis suggested that he and the archivist could keep this secret, since it was not germane to the archivist's planned book. The correspondence ends with the archivist sending the marquis the call number of the book in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris from which he drew his information.

Other observers of the situations saw the Jews as bearers of spiritual deficiencies that could not be overcome. The fact that Jews had accepted the superstitious views of their rabbis for centuries could be an incurable trait rather than one that could be overcome by education and assimilation. Hence, two views developed similar to those about why blacks are black, regarding the Jews. One thought that the difference between Jews and non-Jews was the outmoded adherence on the part of Jews to certain practices and views and that Jews could change this by altering their activities and beliefs. The other view was that there was a basic characteristic that made Jews Jews, and that this was a spiritual feature, a spiritual disease, which could not be changed.[13] The first view supported public contests, such as the one just before the French Revolution, for the best answer to the question, "How to make the Jews happy and useful in France?" The second view led to secular anti-Semitism, and in our century to the Holocaust.

One might expect that once scriptural explanations were dropped

[13] The view ora special unchangeable characteristic that made Jews different appears in the work of many French Enlightened writers. See the quotations offered in Arthur Hertzberg, The French Enlightenment and the Jews (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), chap. 9; Leon Poliakov, Histoire de l'antsémitismt de Voltaire à Wagner (Paris: Caiman-Levy, 1968), livre I, chap. 2; and Pierre Pluchon, Nègres et Juifs au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Tallandier, 1984); deuxième partie, "Les lumières et les Juifs," 64-81.

The notion that Judaism is a disease appears in remarks of Voltaire where he indicated Judaism had infected Western culture with oriental ideas. At one point he said, "They are, all of them, born with raging fanaticism in their hearts, just as the Bretons and the Germans are with blond hair. I would not be the least bit surprised if these people would not some day become deadly to the human race" (Voltaire, Œuvres complètes, 52 vols., ed. Louis Moland [Paris: Gamier frères, 1877-1885l, 28:439-440).

This theme was taken up in nineteenth-century Germany: see George L. Mosse, Toward the final Solution: The History of European Racism (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), part II, "Infected Christianity." The Nazi theorist, Alfred Rosenberg, cited the Jew, Otto Weiniger, from his Sex and Character as saying Judaism is like an invisible, cohesive web of slime fungus, existing since time and immemorial all over the world. "From all of this it follows that Judaism is part of the organism of mankind just as, let us say, certain bacteria are part of man's body." The bacteria have to be kept under control. Cf. George L. Mossc, Nazi Culture (New York: Schocken Books, 1966), 76-77. Mosse quotes a Nazi judge as saying in 1938, "The Jew is not a human being. He is an appearance of putrescence. Just as the fusion—fungus cannot permeate wood until it is rotting, so the Jew was able to creep into the German people to bring on disaster, only after the German nation, weakened by the loss of blood in the Thirty Years War, had began to rot from within" (ibid., 336-337). And, of course, Joseph Goebbels referred to Judaism as a bacillus.

by intellectual leaders and replaced by the "scientific" ones of the Enlightenment, solely factual considerations would enter into explaining why various groups differ. But, alas, much more was, and still is, involved in accounting for human differences, including what roles various groups should play in social, political, cultural, and economic activities.

In the matter of black Africans, there was considerable research. On one side, scientific data were sought to show the inferiority of blacks, justifying their enslavement and exploitation. The growing group of abolitionists, on the other side, tried to show that blacks, at least potentially, are not inferior intellectually or culturally. The physical differences could be described and explained in anthropological and biomedical terms, but final evaluation seemed dependent upon what one wished to prove.

Starting with skin color, various explanations were offered such as the effect of climate and sunshine. G. S. Rousseau, in the paper he delivered before the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies Conference on racism held in Los Angeles in 1973, examined the views of Claude Nicolas Le Cat, an influential French physician from Rouen (1700-1768), who believed there was a substance in the organic system, ethiops, that made blacks black, and the lack of much of it made whites white.[14] In the earlier-mentioned Turkish Spy, there is a discussion of a medical dissection of a dead Negro. "Between the outward and inward skin of the corps was found a kind of Vascular Plexus spread over the whole Body like a Web or Net, which was fill'd with a Juice as Black as Ink." This web or net, not found in white people, accounted for the skin color, and purported to show that blacks and whites had different origins. The Turkish Spy, who accepted the pre-Adamite theory, used this dissection as further evidence for his antibiblical views.[15] In another argument, an elaborated theory of climate, diet, and way of life was developed by the great biologist, Count Buffon, 1707-1788, to explain differences in skin color. (Buffon claimed that all babies are born white,

[14] On this, see G. S. Rousseau, "Le Cat and the Physiology of Negroes," in Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture, vol. 3, Racism in the Eighteenth Century, ed. Harold E. Pagliaro (Cleveland: Press of Case Western Reserve University, 1973), 369-386.

[15] Marana, Turkish Spy 8:265, See the discussion of the Turkish Spy's pre-Adamism in Popkin, Isaac La Peyrère, chap. 9; and "A Late-Seventeenth-Century Gentile Attempt to Convert the Jews to Reformed Judaism," in S. Almog et al., Israel and the Nations: Essays Presented in Honor of Shmuel Ettinger (Jerusalem: Historical Society of Israel and Zalman Shazar Center, 1987), xxv-xlvii.

and then some soon, within eight days, became black for environmental reasons.)[16]

Aside from the question of what is scientifically the case, the discussions during the eighteenth century involved two other matters: (l) was the condition, skin color, permanent? and (2) was this condition organically related to black intellectual and cultural inferiority? Similar issues developed concerning variation of European and African hair, that is, what physiologically causes the differences; is the difference permanent; and, is it related to the crucial matter of supposed black cultural and mental inferiority? The mere fact of the difference could be trivial, as between varieties of eye color or hair color, or it could be part of a systematic set of differences to prove that blacks were not of the same race, or even species as whites. And, there are even some attempts to find medical and biological similarities between blacks and monkeys as part of the quest for a major, even monumental, difference theory between whites and blacks. Various doctors who traveled to different parts of the world reported on physiological differences. John Atkins, an English naval surgeon, concluded that whites and blacks were different in some basic physical features.[17] Unlike Le Cat, Atkins did not try to determine the exact physiology of the differences. We are told that Baron de Lahotan, voyaging to America, had a dispute with a Portuguese doctor who had been in Angola, Brazil, and Goa about what factors accounted for differences amongst peoples. The Portuguese doctor insisted the native Americans, the Asians, and Africans each had to have different fathers. Baron de Lahotan offered both scriptural evidence and a theory that air and climate could account for the color differences.[18] There was also a doctor, John Mitchell, who offered a counter-theory to the view that mankind began as white, and because of dimate and so forth, some people became dark and even black. Mitchell claimed the original state of people was closer to that of Indians and Negroes than to that of

[16] Georges Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Natural History, General and Particular, trans. William Smellie, 2d ed., sec. 9, "Of the Varieties of the Human Species." On this, see R. H. Popkin, "The Philosophical Bases of Modern Racism," in The High Road to Pyrrhonism, ed. R. A. Watson and James E. Force (San Diego: Austin Hill Press, 1980), 86-87.

[17] John Atkins, Surgeon, The Navy-Surgeon; or, A Practical System of Surgery (London, 1734), Appendix on observations about conditions on the Coast of Guiney, pp. 23-24. Atkins concluded, "From the Whole, I imagine that White and Black must have descended of different Protoplasts; and that there is no other way of accounting for it."

[18] Lom d'Arce, Nouveaux voyages de M. de Baron de Lahontan dans l'Améique septen-trionale (The Hauge, 1703), letter dated Nantes, 10 mai 1693, 249-253.

Europeans.[19] The great biological classifier, Linnaeus (1707-1778), in his description, implied much about the significance of the differences. He stated that the Europeans were "fair, sanguine, brawny. Hair yellow, brown, flowing; eyes blue, gentle, acute, inventive. Covered with close garments. Governed by laws." In contrast, the African was "black, phlegmatic, relaxed. Hair black, frizzled; skin silky, nose flat; lips tumid; crafty, indolent, negligent. Anoints himself with grease. Governed by caprice." Linnaeus included physical differences as well as cultural, social, and intellectual ones, stated beneficially for Europeans and disparagingly for Africans.[20]

The eminent Scottish philosopher David Hume, neither biologist, medical student, nor anthropologist, stated the extreme interpretation of the differences as they presented themselves in the cultural achievements of both groups. In his essay "Of National Characters," Hume added the following in a note:

I am apt to suspect the negroes and in general all other species of men (for there are four or five different kinds) to be naturally inferior to the whites. There never was a civilized nation of any other complexion than white, nor even any individual eminent either in action or speculation. No ingenious manufactures amongst them, no arts, no sciences. On the other hand, the most rude and barbarous of the whites, such as the ancient GERMANS, the present TARTARS, have still something eminent about them, in their valour, form of government, or some other particular. Such a uniform and constant differences could not happen in so many countries and ages, if nature had not made an original distinction betwixt these breeds of men [my emphasis]. Not to mention our colonies, there are Negroe slaves dispersed all over Europe, of which none ever discovered any symptoms of ingenuity, tho' low people, without education, will start up amonst us, and distinguish themselves in every profession. In JAMAICA indeed they talk of one negroe as a man of parts and learning; but 'tis likely he is admired for very slender accomplishments like a parrot, who speaks a few words plainly.[21]

As I have argued elsewhere, Hume's empirical theory of knowledge does not commit him logically to any particular view on this subject. The view he offered was presented as an empirical generalization and an

[19] John Mitchell, "An Essay upon the Causes of the Different Colours of People in Different Climates," Royal Society of London Philosophical Transactions 43 (1744-45): 146.

[20] Linnaeus (Karl yon Linne), A General System of Nature through the Three Grand Kingdoms of Animals, Vegetables and Minerals (London: Lackington, Allen, 1806), I, section "Mammalia. Order F. Primates."

[21] David Hume, "Of National Characters," in The Philosophical Works of David Hume, ed. T. H. Green and T. H. Grose (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1882), 3:252n.

explanation of it.[22] However, Hume ignored all the evidence contrary to his theory, some of which will be considered shordy. There was plenty of empirical evidence to counter Hume's generalization. Hume's Scottish opponent James Beattie spent dozens of pages showing the factual falsity of Hume's views and their malevolent influence.[23] Hume discussed Beattie's whole critique by calling him "a silly—bigotted" fellow.[24] So, to my mind, Hume must be recognized as personally very prejudiced, unwilling to use his philosophical standards on this subject, and unimpressed by the fact that defenders of slavery were quoting him, and saying "as the learned philosopher David Hume has proved." The fact was, his thoughts were just a bundle of perceptions that had nothing to do with skin color. Hume's philosophy may have been racially neutral, but Hume the philosopher was not.

Hume was quoted approvingly over the next half-century by defenders of slavery in the Americas,[25] but he offered no account of the original physical difference that caused the enormous cultural and intellectual difference between whites and blacks. Skin pigmentation did not seem to indicate any cause, except that dark pigmentation was usually interpreted as a degenerative effect from the original white complexion of the entire human race. The first American edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica described the many bad characteristics of Africans and offered as an explanation only that the Negroes "are an awful example of the corruption of man when left to himself."[26]

In the early nineteenth century, an American medical doctor, Samuel Morton of Philadelphia, in his Crania Americana, claimed to have discovered the cause of Negro inferiority in the lower cranial capacity of blacks. Morton had the largest skull collection in the world. He stuffed up the orifices of his skulls, filled them with pepper seed, and reported that the Caucasian skulls held the most pepper seed, the blacks the least, with Asiatics and American Indians in between.[27] (The eminent biologist

[22] R. H. Popkin, "Hume's Racism," The Philosophical Forum 9 (1977-78): 211-218.

[23] See James Beattie, Essays on the Origin and Immutability of Tnah, ad ed. (Edinburgh, 1776), 310 ff.

[24] Hume, "Advertisement," which appears in all editions of Hume's work after Beat-tie's attack (which first appeared in 1770). This dismissal of Beattie as a bigot first appears in Hume's Letters, ed. J. Y. T. Greig (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1932), 2:301.

[25] Cf. Popkin, "Hume's Racism," 221-222.

[26] Encyclopaedia Britannica, 3d ed. (Philadelphia, 1798), s.v. "Negro."

[27] See Samuel G. Morton, Crania Americana; or, A Comparative View of the Skulls of Vari-mss Aboriginal Nations of North and South America; to Which Is Prefixed and Essay on the Varieties of the Human Species (Philadelphia and London, 1839), and Crania Aegyptiana; or, Observations on Egyptian Ethnography, Derived from Anatomy, History and Monuments (Philadelphia, 1844).

On Morton, see William Stanton, The Leopard's Spots (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1960); and R. H. Popkin, "Pre-Adamism in Nineteenth-Century American Thought: 'Speculative Biology' and Racism," Philosophia 8 (1978): 219-221.

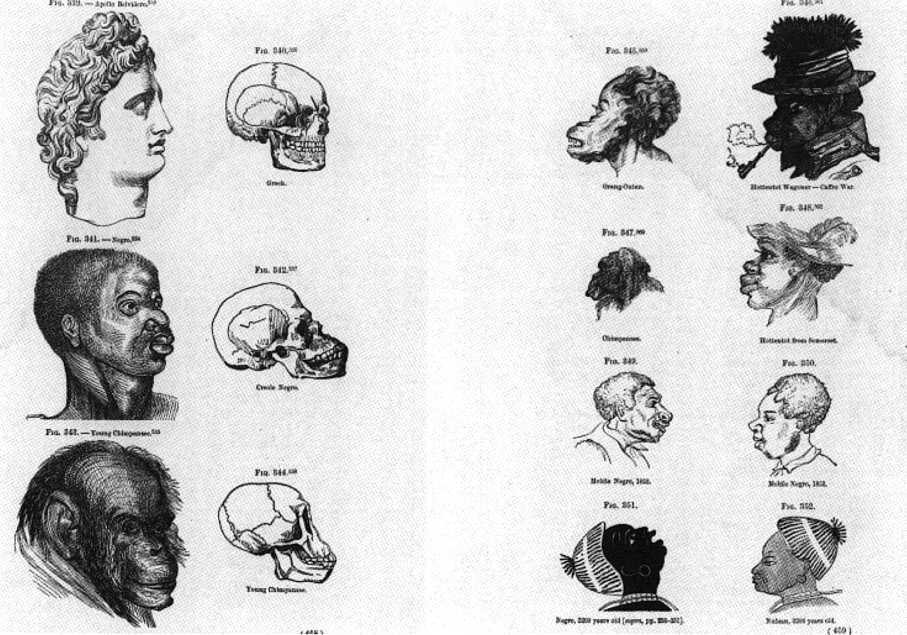

Pl. 22. Skull comparisons of Caucasians, Negroes, and monkeys, from Josiah Clark Nott, Types of Mankind (Philadelphia, 1854), a memorial volume for Dr. Samuel Morton.

Steven Jay Gould, who has written extensively on the history of biological theories, examined Morton's researches and concluded that Morton reported only those cases which allowed him to "fudge" his data by leaving out some results and using uneven measurement techniques that allowed more pepper seed to fill some skulls than others.[28] Morton's work was followed with a study by an Italian, Filippo Manetta, in his La razza negra nel suo stato selvaggio. Manetta's work was not translated, but it was extensively quoted and explained in an article entitled "Negro" in the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Manetta claimed that the cranial sutures of Negroes close much earlier than in other races: "to this premature ossification of the skull, preventing all further development of the brain, many pathologists have attributed the inherent inferiority of the blacks, an inferiority which is even more marked than their physical differences." Manetta's theory was that white and black children are born with equal intelligence but that at puberty, when the brain sutures close, all further intellectual development in blacks ceases.[29] The famous eleventh edition of the Britannica recorded Manetta's theory and added that evidence was lacking to settle the matter, but "the arrest or even deterioration in mental development is no doubt very largely due to the fact that after puberty sexual matters take the first place in the negro's life and thought."[30] And so, second to skin color, intellectual inferiority became another crucial difference. Physiological features, such as alleged smaller skull capacity or sealing of the brain sutures, became the accepted causes of black insufficiency. This account was finally removed in the present, fifteenth, edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.[31] The major issue then became whether biological or environmental factors could alter the situation or whether it was a fixed condition.

Hume, Dr. Morton, and a host of others held to a polygenetic theory about human origins, and maintained that the state of affairs was unchangeable. Still, the abolitionists and advocates of human equality

[28] Stephen Jay Gould, "Morton's Ranking of Races by Cranial Capacity: Unconscious Manipulation of Data May Be a Scientific Norm," Science 200 (1978): 503-509.

[29] See "Negro" by Prof. A. H. Keane (of University College, London), Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9th ed. (New York, 1884), 17:317.

[30] "Negro" by Thomas Athol Joyce, Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th ed., 19:344.

[31] The present, fifteenth, edition, gives a neutral account of how Negroes differ from other races, followed by a section on "Negro, American," listing Negroes from the eighteenth century to the present who have made a significant contribution to American life.

insisted on the possibility of change in the intellectual achievements of blacks. Buffon, the leading biologist of the period; Blumenbach, the eighteenth-century "founder of modern anthropology," and various theologians and progressive-minded philosophers insisted that change was possible through environmental alterations such as moving people to healthier climates, through changing their diets, and through social engineering in terms of education, life-style, and so forth. They also believed that the best evidence of their remedial theory was the fact that black intellectuals and creative artists already existed, and presumably many, many more would come into being if environmental, biological, and social change took place.[32] There is an amazing literature in the eighteenth century, arguing against Hume, and later Thomas Jefferson, who made similar claims of black inferiority. Jefferson once ended his discussion saying,

I advance it, therefore, as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowment both of mind and body.

Jefferson gave as a possible reason, black color:

Whether the black of the negro resides in the reticular membrane between the skin and scarfskin, or in the scarfskin itself; whether it proceeds from the color of the blood, the color of the bile, or from that of some other secretion, the difference is fixed in nature, and is as real as if its seat and cause were better known to us. And is this difference of no importance? Is it not the foundation of a greater or less share of beauty in the two races?[33]

But as Henry Lewis Gates has shown, most of the cases that failed were the result of deliberate manipulation.[34] In a more positive vein, Gates

[32] Johann F. Blumenbach, On the Ncaurcd Varieties of Mankind, trans. Thomas Bendyshe (New York: Bergman Publishers, 1969), 305-312; and Henri Grégoire, De la lit-tércaure des nègres (Paris, 1808), chaps. 5-8. See also Popkin, "Philosophical Bases of Modern Racism," 86-89.

[33] See Winthrop D. Jordan, White over Black (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968), "Jefferson: The Assertion of Negro Inferiority," pp. 435-440; and Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (1782), in The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Paul Leicester Ford (New York and London, 1894), 3:244-250 (the first of the quoted passages appears on p. 250, the second on p. 244).

[34] In a personal meeting with Professor Gates in 1981, he shared with me his dissertation done at Cambridge on black writers and artists in the eighteenth century. A revised version has been published as Henry L. Gates, The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of Afro-American Literary Criticism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988).

tells how the Duke of Brunswick raised some black children with his own at Wolfenbüttel in Lower Saxony. One of these blacks (A. W. Amo) became Professor Amo of the University of Halle.[35] Also, the Governor of Jamaica raised a black boy, named Francis Williams, and sent him to Cambridge. Afterward, Williams returned to Jamaica, took charge of a school, and wrote Latin poetry. Williams was the same man Hume insulted by saying he was like a parrot who spoke a few words plainly.[36] The most famous case was Phillis Wheatley, a young West African woman settled in Boston who wrote poetry in English. She was considered such a sensation that public poetry sessions were held, where she sat surrounded by witnesses and wrote her verse. In fact, General George Washington sat in a special session. Eventually, Wheatley was taken on tour in England and was exhibited hither and yon as a black creative artist and intellectual, a living disproof of the racist views of Hume and Jefferson that the "defects" of blacks were irremediable.[37] Jefferson dismissed her case, saying her poetry was mediocre, and besides, she was a mulatto.[38] Hume said not a word about any of these cases and never revised his statement on the matter.

The racists of the eighteenth century contended that the dark complexion of the Africans was an irremediable defect that was part of a fundamental, unchangeable set of defects that made blacks inferior to whites. The human body, they maintained, limited or determined what mental development was possible. The body fixed the space the brain could occupy, and presumably brain size related to mental capacity. Dr. Morton's theory or Dr. Manetta's contended that bodily conditions, smaller cranial capacity, or early closed cranial suture accounted for lesser black mental ability. The actual scientific reasons for these differences were of less concern than the overall conclusion they pointed to, that blacks were of a different species than whites. Some form of polygenetic theory would explain how the difference began and continued, and this in turn justified keeping the blacks in an inferior status indefinitely.

[35] On Amo, see K. A. Britwum, s.v. "Amo, A. W.,' in Dictionary of African Biography 1:196-197. He is also discussed in Grégoire's Littérature des nègres, 198-202.

[36] On Wiiliams's career, see Grégoire, Littérature des nègres, 236-245. One of Williams's Latin odes is published there. Williams and his rection to Hume's remark is discussed at length in Gates's dissertation.

[37] Phillis Wheatley is discussed in Grégoire, Littérature des négres, 260-272, and at length in Gates's dissertation.

[38] See Jefferson's Notes from Virginia, 246. "Religion, indeed, has produced a Phyllis Whately [sic ]; but it could not produce a poet. The compositions published under her name are below the dignity of criticism."

Pl. 23. Portrait of Phillis Wheatley on the title page of the 1773 London edition of her poems.

Those opposing this conclusion denied that the physical differences implied different species. Mostly, they contended that the differences in blacks from whites were degenerative, but reparable with time, effort, and good will. The emergence on the scene of black intellectuals and creative artists, usually engineered by careful nurturing, showed proof that the intellectual faculties could be awakened and restored. Such able scientists as Count Buffon believed the physical differences could be overcome in ten generations by moving blacks to a geographical band extending from northern France to the Caucasus Mountains, feeding them a good French diet, and giving them an Enlightenment education.[39] Even the most ardent abolitionists conceded that at the present time almost all blacks were in poor physical condition, and as a result were intellectually limited. The polygenetic racists, in opposition, insisted that the poor physical condition (except for ability to do hard labor under appalling conditions) was simply a sign of permanent mental inferiority. The body was the carrier of the difference, and it limited the mind, as in the theory of cranial capacity of Dr. Morton or the theory of early suture closing of Dr. Manetta. The remedialists saw the bodily differences as causing mental inferiority and believed that improving the physical conditions would improve mental abilities and that black Platos, Homers, and Pindars would soon evolve. The argument, of course, is ongoing as to whether the apparent differences in intellectual abilities between different races are due to distinct somatic conditions that are basically unalterable or to environmental conditions both inside and outside the individuals in question: one has moved from the scientific inquiries of Dr. Le Cat, Count Buffon, and Professor Stan-hope Smith, Professor of Moral Philosophy at Princeton, to investigations about IQs and genetic factors that may be related to mental development.

Turning from color racism, which was secularized in the Enlightenment by justifying it on the basis of somatic distinctions between races, and the effects these were presumed to have, to the secularization of anti-Semitism, one first has to recognize that different factors and interests were involved. Color racism justified black slavery and colonialism. The Jews, especially those of western Europe where modern secular anti-Semitism developed, were neither slaves nor possessors of any territory to be colonized. In fact, from Shylock's speech onward,

[39] Buffon, Natural History, vol. 3, sec. 9, PP. 57-207. On p. 207, Buffon said that the present unfortunate situation could be changed and improved if the causes that generated them—climate, food, mode of living, epidemic diseases, and the mixture of dissimilar individuals—ceased to operate.

about how much Jews were like everyone else, there was a recognition that physically Jews were like Europeans or Caucasians except for possibly a different smell, a slightly different coloring, a slightly different nasal configuration. A converted Jew outside of Iberia was an accepted and acceptable member of his society. The alleged Jewish smell disappeared, whether by Divine Providence, or by accepting general European washing practices. Jews became just swarthy people, of Levantine or Iberian extraction; facial characteristics were no longer matters of significance. La Peyrère, presumably himself a convert, or a child of converts, had said the darkish color would change in the course of conversion by divine action.[40] And the other physical features like the Semitic nose were overlooked.

There were many prominent converts all over Europe during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, and except in Spain and Portugal, they were accepted as coequal members of society. Michel de l'Hôpital, Chancellor of France under Catherine de Medici, was a convert. So was Antoinette Lopes, mother of Michel de Montaigne. Nostradamus, the notorious French court astrologer, was the grandson of two rabbis, both of whom converted. There were professors in England, Tremellius in France, Philippe d'Aquin and Paulus Ricci in Rome, and many others who had personally converted. Bayle's Dictionary contains many biographies of university professors, political advisers, Hebrew and Arabic scholars who converted. And Bayle considered the evidence about whether Jean Bodin among others was of Jewish origin.

There was a steady trickle of converts during the Renaissance period through the Enlightenment. Whether they converted from conviction or for advantage, they were almost always accepted in their new roles. One became Harvard's Hebrew professor, another an advisor to an Anglican bishop, others court bankers and advisers. By the end of the eighteenth century, Moses Mendelssohn's children became converts, and one, Dorothea Schlegel, became a prominent intellectual and salon hostess. As Hannah Arendt has shown, in the secular early nineteenth century the converts began to find their situation strained and, for some, even

[40] La Peyrère, Du Rappel des Juifs, 8: "Les Juifs en ce temps la n'auront plus cette couleur noire et bazanée qu'ils ont contractée en leur Exil….Ils changeront de visage dans ce Rappel, et la blancheur de leur teint aura le même éclat, dit le Psaume qu'ont les ailes et la gorge d'un pigeon extrêmement blanc."

Malcolm X, having read about Spinoza when he was in jail, concluded from the fact that he was described as dark and swarthy, that Spinoza was black. "Spinoza impressed me for a while when I found out he was black. A black Spanish Jew" (Autobiography of Malcolm X [New York: Grove Press, 1966], 180).

untenable. Without acceptance into the Jewish community they felt they no longer had roots. Rahei Varnhagen, a nineteenth-century salon hostess and the heroine of Arendt's work, even committed suicide.[41] Others went on to become leading figures in the missionary movements, and one became the first Anglican bishop of Jerusalem.[42]

If converts were easily acknowledged except in the Inquisition world, what was the real difference between a Jew and a non-Jew? Even Old Christian Spaniards and Portuguese believed that the essential and important difference was mental or spiritual. They could describe this in terms of malign beliefs condemned by God. But for an eighteenth-century secular humanist, what difference should Jewish beliefs have made? Jews, however, could be and were classified as superstitious, unreasonable, and unenlightened by Bayle, by various English deists, and by many philosophes.[43] And it was accepted that living according to these unfortunate beliefs could lead to some physical disabilities because of dietary restrictions, the conditions of ghetto life, and the imposed poverty, enforced by the nasty Christian ancien régime. For people who saw what was later to be called "the Jewish question," all one needed to do to resolve or dissolve the problem was to enlighten Jews so that they became just ordinary rational Europeans. There was no shortage of evidence that Jews had the intellectual equipment to participate in European civilization. From Philo Judaeus and Flavius Josephus to Moses Maimonides to Leon de Modena, to Menasseh ben Israel to Isaac de Pinto and Moses Mendelssohn, there were a stream of significant figures who played an important role in the history of European ideas, their Jewishness notwithstanding.[44] The roles of de Pinto and Mendelssohn

[41] Hannah Arendt, Rahel Varnhagen: Lebengeschichte einer deutschen Jüdin aus der Romantik (Munich, 1962).

[42] The leading missionary for the London Society for Promoting Christianity amongst the Jews was Joseph Wolf, a convert. The leading figure in the American Society for Ameliorating the Condition of the Jews was Joseph Frey, a convert who gave thirty thousand sermons in America. The first Anglican Bishop of Jerusalem was Michael Solomon Alexander, 1799-1843, chosen because he could speak to Jesus on His Return in his native tongue.

[43] The philosophes will be discussed shortly. Regarding the views of the English deists about the Jews, see S. Ettinger, "Jews and Judaism as Seen by the English Deists of the Eighteenth Century" (in Hebrew), Zion 29 (1964): 182-207. For Bayle's view, see his many articles on Old Testament characters in the Dictionnaire historique et critique. See also Hertzberg, French Enlightenment, chap. 3.

[44] The theme was developed at length in such works as Jacques Basnage, L'histoire et la religion des Juifs, depuis Jésus-Christ jusqu'à prèsent, pour servir de supplément et le continuation à l'histoire de Joseph (Rotterdam: R. Leers, 1706-1707, and later editions); Henri Grégoire, Essai sur la régénération morale et politique des Juifs (Metz, 1789), and Honoré Gabriel Riquetti, Marquis de Mirabeau, Sur Moses Mendelssohn, mr la réformt politique des Juifs (London, 1787).

Pl. 24. Title page of Isaac de Pinto's Traité de la circulation et du crédit (Amsterdam, 1771).

Pl. 25. Portrait of Moses Mendelssohn, from an urn in the Stadtsmuseum of Braunschweig, Lower Saxony.

in eighteenth-century Enlightenment discussions was of the highest significance. De Pinto was one of the first modern economists, a friend of Hume and Diderot, and a protagonist of Voltaire, while being the leader of the Amsterdam Synagogue.[45] Mendelssohn, the Jewish Socrates, was

[45] On de Pinto, see R. H. Popkin, "Hume and Isaac de Pinto," Texas Studies in Literature and Language 12 (1970): 417-430; and "Hume and Isaac de Pinto, II: Five New Letters,' in Hume and the Enlightenment: Essays Presented to Ernest Campbell Mosmer, ed. William B. Todd (Edinburgh: The University Press, 1974), 99-127, 428-429. In the first essay, I discuss de Pinto's role in the history of economic theory, from his refutation of Hume's essay on the national debt, to the discussion of de Pinto's views in Adam Smith, Dugald Stewart, Karl Marx, Werner Sombart, and others. Marx called de Pinto "the Pindar of the Amsterdam Bourse" (note in Das Kapital, vol. 1, pt. 2, chap. 4, P. 165, in Marx-Engels Werke, vol. 23 [Berlin, 1962]). Sombart said that de Pinto was the first person to see clearly "dass die Entwicklung des modern Kreditsystems von der Vermehrung des Edelmetalle abhangig ist" (Der Modern Kapitalismus, III, Das Wirtshaftsleben in Zeitalter des Hochkapitalisraus [Berlin, 1955], 191).

a friend of Lessing's, the sponsor of Kant, perhaps the leading figure of the German Enlightenment, while remaining an orthodox Jew.[46]

In both cases, irreligious or deist friends of Christian origin still indicated that there was some difference between de Pinto and Mendelssohn and other Europeans. Hume was more philo-Semitic than most of his contemporaries, and defended the Jews in his History of England,[47] giving a quite anti-Christian explanation of their mistreatment and expulsion from England in the Middle Ages. Hume was very friendly with de Pinto and worked hard to get him a pension from the East Indian Company. He dined with de Pinto and discussed politics and economics with him. But in writing about him, and for him, Hume felt he had to make the point that he was a good man, "tho" a Jew.[48] This may have been because the people Hume was dealing with, government leaders and India Company officials, were too conscious of de Pinto's Jewishness and not sufficiently aware of his goodness. De Pinto had other important backers, such as Lord Clive and the Duke of Bedford, who could just recommend him without qualification.[49] Lessing promoted Mendelssohn in all sorts of ways, but would not take him to, or propose him to, his lodge of the Freemasons because he was a Jew.[50] But what could this mean for Hume or Lessing? Lessing wrote Nathan the Wise expounding that Jews were like everybody else, a work that helped emancipate the German Jews. But like Hume, Lessing could still sense some difference that remained even in the most enlightened Jews. However, when the Swiss physiologist, Lavater, wrote Mendelssohn saying that if he was so ra-

[46] For some background on Mendelssohn's career, see Alexander Altmann, Moses Mendelsson: A Biographical Study (University: University of Alabama Press, 1973).

[47] See the selections from David Hume's History of Englaud on the Jews in medieval England in David F. Norton and Richard H. Popkin, David Hume, Philosophical Historian (Indianapolis: Bobbs Merrill, 1965), 119-126.

[48] Letter to Thomas Rous, 28 August 1767, published in Popkin, "Hume and Isaac de Pinto, 11," 104.

[49] On this see the account in Popkin, "Hume and Isaac de Pinto, II."

[50] Jacob Katz, Jews and Freemasons in Europe (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970), 25. Altmann, Moses Mendelssohn, 311, commenting on Lessing's discussions about Freemasonry with Mendelssohn, said "Mendelssohn had never made an effort to enter the order as many Jews of the next generation would do with varying success."

tional, he had to become a Christian, Lessing, along with Herder and others, answered that there was no need for Mendelssohn to convert.[51] Mendelssohn kept out of the argument until his final work Jerusalem (written in 1786), where he defended Judaism and claimed he and his Enlightenment friends shared a common rational religion, and that he and other Jews had in addition a set of revealed laws they had to keep. Thus, for Mendelssohn, Jews, rationally, were or could be like everybody else, but religiously they were different. So, in Mendelssohn's own view, and in the view of his Enlightenment friends, some distinction remained. They could discuss Plato and Spinoza and human freedom, but Mendelssohn kept a kosher house.[52]

The enlightened Jews of Holland also insisted on some difference when the French Revolutionary armies conquered Holland and established the Batavian Confederacy. The French tried to enforce the new French law making Jews citizens. Both the Jewish leaders and the Dutch Calvinists joined in insisting they did not want Jews to be turned into Dutchmen. The Jews maintained they enjoyed Dutch hospitality, and enjoyed their status as legal residents, but they did not want to be Dutch, because they expected to go to their own home when the Messiah finally arrived. The orthodox Calvinists insisted the future of all mankind depended on Jews remaining separate. Only then could they play out their role in Divine History leading to the millennium.[53]

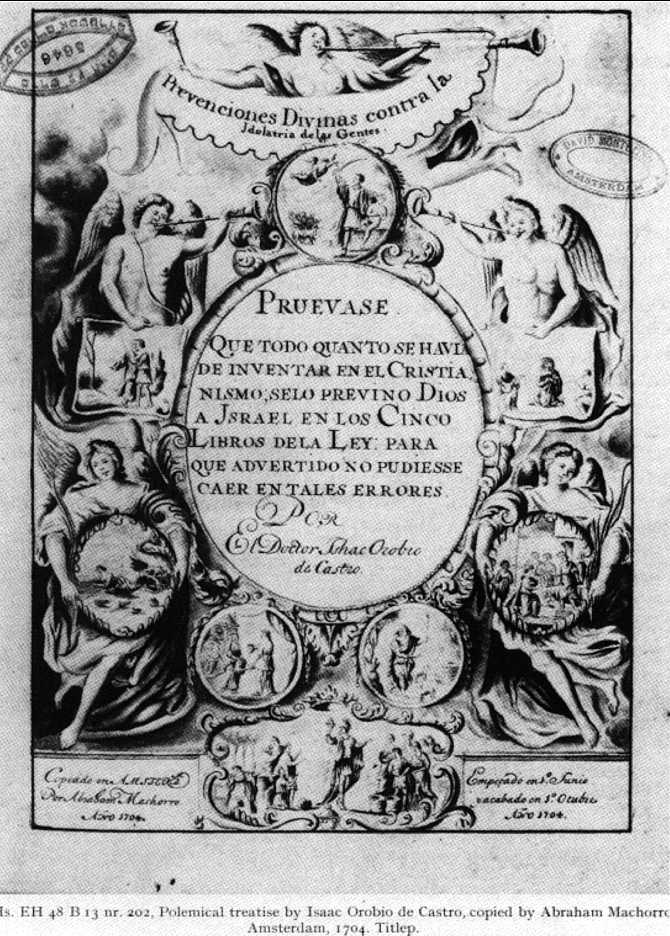

At the beginning of the Enlightenment, Dr. Isaac Orobio de Castro, one-time royal physician in Spain, later professor in the medical school at the University of Toulouse, and finally eminent physician in Holland (where he treated Queen Sophie of Prussia), wrote against Spinoza and publicly debated Philip van Limborch in the presence of Doctor John Locke on the truth of the Christian religion. Neither Locke nor van Limborch doubted the intellectual ability of Orobio, and they saw his spiritual blindness as some kind of Jewish flaw.[54] Jacques Basnage, the

[51] On the Lavater affair, see Altmann, Moses Mendelssohn, chap. 3.

[52] On Mendelssohn's Jerusalem, see Altmann, Moses Mendelssohn, 514-552.

[53] See the texts of the debate in Holland, published by S. E. Bloemgarten, "De Amsterdamse Joden gedurende de eerste jaren van de Bataafse Republick 0795-1798)," I, II, III, Studia Rosenthaiiana 1, no. 1 (1967): 66-96; 1, no. 2 (1967): 45-70; 2, no. 1 (1968): 42-65.

[54] On Orobio de Castro, see Yosef Kaplan's Isaac Orobio de Castro, and His Circle (in Hebrew; summary in English) (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1982). The work was published by Oxford University Press in an English translation in 1990.

Locke and Limborch discussed Orobio at length in their correspondence. See letters

958, 959, 963, and 964 in The Correspondence of John Locke, ed. E. S. De Beer, vol. 3 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978).

Pl. 26. Scenes from the life of Dr. Orobio de Castro, including his having been a royal physician in Spain and professor of medicine at Toulouse.

Huguenot scholar already mentioned, who wrote the first history of the Jews since Josephus, was very concerned with the failure of the debates between Jews and Christians to bring about Jewish conversions. Basnage, following a project outlined by Menasseh ben Israel, to show how Jewish history after the Fall of the Temple was Providential up to the present, put together a vast body of information and material into a huge history showing God active in both chastising the Jews for their spiritual blindness, and protecting them because of their ultimate role in the imminently forthcoming millennium. Basnage saw the debates as hardening Jewish resistance for intellectual reasons—the Jews knew the theological material better, and they were clever arguers. Therefore, at the conclusion of his work, he urged Christians not to carry on any more debates, but rather to leave it to God to change the mental and spiritual attitude of the Jews.[55]

All of this indicates that the difference felt or sensed by eighteenth-century thinkers between Europeans and Jews centered on a mental or spiritual factor rather than a physical one. An exception should be noted. Spinoza mentioned the possibility that all of the generations of circumcising Jewish males may have made them too effeminate to play any further role in history. He states:

The sign of circumcision is, as I think, so important, that I could persuade myself that it alone would preserve the [Jewish] nation for ever. Nay, I would go so far as to believe that if the foundations of their religion have not emasculated their [the Jews'] minds they may even, if occasion offers, so changeable are human affairs, raise up their empire afresh, and that God may a second time elect them.[56]

An attempt to delineate the difference started appearing in the writings of the English deists and the French philosophes. Their anti-Christianity should, and often did, remove the Christian anti-Semitic prejudices from their perspective. But only a few therefore became philo-Semites (like John Toland or Montesquieu).[57] Others began stress-

[55] Cf. Basnage, Histoire des Juifs. An English translation appeared in 1708. Basnage's work is an all-important source for seeing the place of the Jews in the Christian world circa 1700. The work is just beginning to be taken seriously as a significant contribution.

[56] Benedictus de Spinoza, Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, ed. R. H. M. Elwes (New York: Dover Press, 1951), chap. 3, P. 56. This text has been seized upon over and over again to show that Spinoza was a proto-Zionist, or that he still harbored Jewish leanings long after his excommunication.

[57] See John Toland, Nazarenus: A Jewish and Gentile and Mahometan Christianity (London, 1718), and the citations from Montesquieu's writings given in Hertzberg, French Enlightenment, 273 ff.

ing the nasty ancient Jewish views and activities that spawned the great menace of the last millennium and a half, Christianity. Judaism was the foul root on which Christianity grew. Old Testament morality was really immorality when seen from an enlightened perspective. All sorts of mind-boggling and mind-limiting activities introduced from Moses to New Testament times infected Christianity and made it so bad. And Judaism retained those primitive customs and practices of ancient times, which enlightened theorists believed might reinfect Christianity and the Christian world.[58]

For some, a program of enlightened activity could change Jews into reasonable Europeans. The Royal Society of Metz, where the largest number of Jews in France lived, announced a prize essay contest in 1785 on the question, "How to make the Jews happy and useful in France?" The question reflected the problems of the Jews in the area, many of whom were very poor and engaged in marginal or dishonest economic activities.[59] The abbé Henri Grégoire, a priest from a heavily Jewish area in Alsace, wrote one of the prize-winning essays, entitled Essai sur la régénération physique, morale et politique des Juifs.[60] Grégoire saw the Ashkenazi Jews of his time as impoverished, unhealthy, immoral and antisocial, all owing to the baleful effects of anti-Semitism and in no wise to Jewish body or mind. The Sephardic French Jews he considered somewhat more enlightened. He envisaged, and during the Revolution and the Napoleonic period fought for, equal civil rights for Jews, which he believed would lead to their becoming physically, morally, and socially like the rest of French population.[61] And Grégoire, one of the greatest millenarians of the time, hoped this meant that Jews and the

[58] Many of the nastiest texts are gathered together in Pierre Pluchon, Nègres et Juifs au XVIIIe siècle: Le racisme au siècle des lumières (Paris: Tallandier, 1984), "Les lumières et les juifs," pp. 64-82. See also Poliakov, Histoire de l'antisémitisme, livre I, chap. 2, "La France des lumières," pp. 87-160.

[59] On the background of the essay contest, see Hertzberg, French Enlightenment, 328 ff., and Poliakov, Histoire de l'antisénitisme, 167-173.

[60] These were two other winners of the prize, a Protestant, Adolphe Thiery, and a Jew, Zalkind-Hourwitz. All the essays have been republished by Editions d'Histoire Social in Paris in a series entitled La Révolution française et l'emancipation des Juifs. Grégoire's also appeared in English, and it is this that influenced discussions and policies in France during the Revolution of 1787-1831. On Grégoire's role, see Ruth Necheles, Abbé Grégoire: The Odyssey of an Egalitarian (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1971), and R. H. Popkin, "La Peyrère, the Abbé Grégoire and the Jewish Question in the Eighteenth Century," Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 4 (1975): 209-222.

[61] Grégoire, Essai, passim.

Pl. 27. Portrait of the abbé Henri Grégoire (18th cent.).

rest of the French population would become true Christians, ready for the millennium.[62]

Grégoire represented one side, the one that saw the Jews as the victims of centuries of unjustified religious and political anti-Semitism. If this persecution were abolished, and the Jews were given an Enlightenment education, he believed they would flourish. Intellectually they would produce dozens, hundreds, thousands of Mendelssohns and de Pintos. The Jew would be regenerated by the Revolution that would spread Enlightenment to the four corners of the world.[63]

As Grégoire found out, when he started his campaign for Jewish civil equality in 1787 and introduced a bill to establish it in 1789, he was opposed by radical intellectuals quoting Voltaire, Diderot, d'Holbach, and other Encyclopedists and philosophes .[64] Voltaire, Diderot, and d'Holbach were all quite virulent anti-Christians who in the course of their literary careers made a range of observations about the Jews. Since the publication of Arthur Hertzberg's book The French Enlightenment and the Jews (1968), many studies have tried to explain the context of these authors' remarks and to contend they were not really anti-Semites.[65] Among others, Voltaire said many different things, some of which became, whether intended or not, the basis of secular anti-Semitism and of the Aryan mythology. Diderot's early writings on the Jews in the Encyclopédie became a stock source for secular anti-Semites. Diderot apparently changed his opinion when he met actual Jews, like de Pinto, when Diderot went to Holland and visited him. D'Holbach was certainly more anti-Christian than anti-Semitic, but his L'esprit du judaïsme has become a classic that is still published by anti-Semitic groups in the Ukraine. Modern interpreters have ranged from seeing these remarks on Judaism by the Enlightenment greats as just typical views of their time, to claiming they are a minor part of their anti-Christian polemics, to saying these are occasional not central views, to the other extreme of seeing them as extreme and uncalled-for anti-Semitism. A recent French study by Pierre Pluchon, Nègres et Juifs au XVIIIe siècle, argues that even

[62] Grégoire's millenarianism dominated his fight for equality of blacks and Jews, and his contributions to the fight for freedom of all sorts of groups. He died while working for Greek freedom in 1831. In his Histoire des sectes réligieuses, Grégoire, in his section on Jews, makes clear his hopes for the millennial union of Jews and Christians. See tome Ill, livre V, chaps, 1-3 (Paris, 1828).

[63] See Grégoire, Essai sur la régénération physique, morale et politique des Juifs, chaps. 25- 27.

[64] See Hertzberg, French Enlightenment,, chap. 10, "The Revolution."

[65] See, for instance, Hugh Trevor-Roper's review of Hertzberg's book in The New York Review of Books, 22 August 1968, 11.

the philo-Semitism of the abbé Grégoire is really anti-Semitic and that the views of Voltaire, Diderot, and d'Holbach are equally inflammatory.[66] Leon Schwartz, however, has shown that, at least in Diderot's case, he changed his mind after meeting Jews and seeing their situation, and became mildly philo-Semitic.[67]

The gist of the theory offered by these great figures of the French Enlightenment was that Judaism was and is an eastern or oriental view and practice, and contained elements that were antithetical to an enlightened European point of view. In contrast, in the widely circulated Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy, the chief protagonist sought to convince the sultan's Jewish agent in Vienna to adopt a rational Judaism, shorn of its peculiar practices, which would be essentially a moral view based on the universal ethical elements in prerabbinical Judaism.[68] I have argued elsewhere that this is an early attempt to convert European Jews to reformed Judaism.[69]

Voltaire and Diderot often characterized Judaism as fundamentally alien to a civilized European view. Voltaire was challenged by de Pinto, who insisted that at least the Spanish and Portuguese Jews, living in Holland, France, and England, were civilized Europeans.[70] (De Pinto had been the secretary of the Dutch Academy of Sciences and gave two unpublished lectures that contain no Jewish elements but only Enlightenment scientific and deist views.)[71] Voltaire brushed aside de Pinto's arguments, and advised him, if he were so intelligent, to become a philosophe. De Pinto's contention that he was a philosophe and a Jew made no sense to Voltaire.[72] Judaism ancient and modern was and is antithetical to a life of reason. Judaism ancient and modern is Asiatic,

[66] Pluchon, Nègres et Juifs, 64-90. See also Poliakov's evaluation of these eighteenth-century figures in Histoire de l'antisémitisme, livre I, chap. 2.

[67] The evolution of Diderot's views on Judaism and his shift from an Enlightenment anti-Semite to a genuine universalist humanist is very well traced and examined in Leon Schwartz, Diderot and the Jews (Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1981). See also my review of Schwartz's book in Eighteenth-Century Studies 18 (1984): 115-118.

[68] See, for instance, Marana, Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy, vol. 4, letter V, pp. 251-259; vol. 5, letter III, pp. 70-71, and letter XX, p. 203.

[69] Popkin, "A Late-Seventeenth-Century Gentile Attempt" (n. 15 above).

[70] Isaac de Pinto, Apologie pour la nation juive; ou, Réflexions critiques sur le premier chapitre du Vile tome des æuvres de M. de Voltaire au sujet des Juifs (Paris, 1762).

[71] These are in the collection of manuscripts of the Ets Haim Library of Amsterdam, now in Jerusalem. I intend to edit these in the not-too-distant future.

[72] Voltaire's main discussions of this theme appear in his Essai sur les maurs et l'esprit des nations (1769), in the articles on the Old Testament in the Dictionnaire philosophique (1764), and in the appendixes to later editions of the Dictionnaire.

uninfluenced by either the good rational forces of the Hellenic or the Aryan Indian world.[73]

The rendition of this theme in Diderot and Voltaire usually allowed or suggested that this basic drawback of Judaism could be overcome by individual Jews if they broke with their traditions and communities. Voltaire's viewpoint, however, especially in Essai sur les m æ urs , was that Europeans could be enlightened and liberated from their Christian past but that Jews are of a different biological stock, which yields their religion and character. It is unlikely that a Jew can overcome or escape his or her innate character. Even if Jews were cured of their religion, their inborn features would remain, and they would be a threat to themselves and to the Europeans with whom they lived. They infected Europe long ago with Christianity, and their natural incurable Jewishness could repeat itself. And so, at least the suggestion was made that Jews be removed from Europe so that their spiritual contagion could be stopped. At least once, Voltaire claimed that Jews were hopeless in the movement to reform humanity.[74]

D'Holbach's L'esprit de judaïsme went a bit further. The author, in his virulent anti-Christian campaign, had published part of Orobio de Castro's polemic against Christianity under the title Israël vengé. He had also published a version of Les trois imposteurs, Moses Jesus et Mohammed, an antireligious work circulated in the early eighteenth century containing material from Hobbes and Spinoza, among others. During the same period he wrote his notorious anti-Jewish work in which he claimed that Europe, where arts, sciences, and philosophy flourished in Greece and Rome, was then taken over by the false dream invented by imposters like Moses to deceive the Jews. Europe has to break with the unbearable yoke of religious institutions and practices to regain its intellectual force. "Leave to the stupid Hebrews, to the frenzied imbeciles, and to the cowardly and degraded Asiatics these superstitions which are as vile as they are mad; they were not meant for the inhabitants of your climate."[75]

[73] See Voltaire's response in his letter of 21 juillet 1762, letter 9791, Voltaire's Correspondence, ed. Theodore Besterman, vol. 49 (Geneva, 1959), 131-132. The abbé Guénée defended the Jewish side in his Lettres de quelques juifs portugais et allemands à M. Voltaire (Paris, 1769) (portugais, allemands et polonais takes the place of portugais et allemands beginning with the 4th ed., 1776). Voltaire answered in Un chrétien contre six juifs, in Œ uvres 29:558.

[74] This theme runs through the Essai sur les mœurs in Voltaire's evaluation of Judaism. Hertzberg, French Enlightenment, 286-299 shows how Voltaire was taken by his contemporaries as advocating anti-Semitism.

[75] On d'Holbach, see Pierre Naville, Paul Thiry d'Holbach (Paris, 1943). The quotation is from d'Holbach's L'esprit dujudaïsme (London, 1770), 200-201.

The esprit of Judaism was thus something foreign to Europe, which had taken over and now must be overthrown. The Jews were the carriers of the esprit and as such were not capable of being true Europeans.[76]

Voltaire, Diderot, and d'Holbach found a basis for discerning a difference between Jews and Europeans: the difference was spiritual, and pretty much incurable. And the Jewish spirit had infected Europe, causing the Dark Ages, and was still a constant threat to the European point of view. In discerning the difference as one related to mind rather than body, these heroes of the French Enlightenment started the pattern of modern secular anti-Semitism. What was different and wrong with Jews was not their role in the Christian world picture but their role as evil influences who infected Europe with Christianity. This esprit was part of the Jew's oriental nature, which did not belong in Western society and was in danger of reinfecting Europe. This analysis blossomed in the twentieth century in the view of Hitler and Goebbels that Judaism is a bacillus that can always infect the Aryan world and can only be stopped by being eradicated.

The study of language and national identity led to a further stage in the saga of the secularization of racism in the Enlightenment, and the theory developed that Jews should be excluded from the new European nation states because their language was foreign to Europe, as was their mental outlook. It was claimed that Jews in Europe retained the social, cultural, and intellectual outlook found in the Jews of the Middle East and Asia.

The history of the discovery of the "source" of European languages is curious. In the seventeenth century, one impetus to such research was the quest for the language of Adam, the language Adam spoke and in which he named everything according to its nature. The Adamic language would therefore contain universal knowledge. Ail sorts of candidates were explored from the obvious Hebrew to the less obvious ones like Dutch, Swedish, and Chinese. The ancient languages of India entered into this only tangentially.[77] The Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy publicized the news that ancient Sanskrit writings contained a historical

[76] The Scientific Academy of the Ukranian Socialist Soviet Republic keeps reissuing d'Holbach's work as if it were news to the present world.

This claim that Jews did not belong in Europe does not seem to have been part of the English opposition to enfranchising Jews there. In the 1753 opposition to Jewish citizenship, economic issues and Christian prejudice seem to have been paramount.

[77] For a discussion of the search for the Adarnic language, see David S. Katz, Philo-Semitism and the Readmission of the Jews to England, 1603-1655 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982), chap. 2.

cosmology long predating biblical events.[78] The first English publication by Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, a century later, translated from the Persian, pointed out the conflict of the Judeo-Christian scriptures and the Indian ones, and resolved it only as an act of faith.[79] Sir William Jones's inquiries into Sanskrit were partly motivated by an interest in showing that the Indian chronological claims were not historically accurate. Jones became the first European Sanskrit expert and reassured European Christians by telling them that the Indian chronology pre-Adam was mythological and that the rest was easily reconcilable with the Bible.[80] In an aside, Jones observed that it might be the case that all European languages from Latin and Greek onward were derivations from Sanskrit but that Semitic languages were not.[81]

Jones's view quickly became the Indo-European language theory of early-nineteenth-century German scholars. Fredrich Schlegei proclaimed that European languages and cultures derived from an ancient Indo-European language that came from the language of the Indian Aryans, namely Sanskrit.[82] Schlegel coincidentally was married to Moses Mendelssohn's daughter, Dorothea, who had converted to European enlightened Christianity.

It took little effort to show some of the implications of the Indo-European language theory. Joined with Herder's theory that each culture expresses its unique "idea," its mind, in its language and literature, European cultures expressed human mental outlooks in the host of languages derivative from Indo-European. Hebrew was not an Indo-European language. Hence it expressed an idea, a mind, and a culture foreign to Europe. European culture developed from Indo-European Hellenic roots and not from Hebraic ones. The culmination of this line

[78] For example, see Marana,Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy, vol. 8, letter 12, pp. 253-258. Some of the same data appear in Charles Gildon's letter in Charles Blount's Oracles of Reason (1693), 182.

[79] Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, A Code of Gentoo Laws, or Ordinations of the Pundits, from a Persian Translation, made from the Original, written in the Shanscrit Language (London, 1776), xxxviii-xxxix and xliii-xliv.

[80] On Jones's life, career, and influence, see the article on him in the Dictionary of National Biography. His contribution to the discussion appears in his essays, "On the Gods of Greece, Italy, and India," "On the Chronology of the Hindus," and "A Supplement to the Essay on India Chronology," in The Works of Sir William Jones (London, 1807), vols. 3 and 4.

[81] In a private letter dated 27 September 1787, Jones wrote, "You would be astonished at the resemblance between that language [Sanskrit] and both Greek and Latin," in Memoirs of Sir William Jones, ed. Lord Teignmouth (London, 1807), 2:128.

[82] Friedrich Schlegel, "Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Inder," in Sämmtliche Werke, vol. 7 (Vienna, 1846).