13

Tibetan Camp

(1908)

We stayed in Tatsienlu at the home of the Sorensens and found mail from America awaiting us. It was wonderful to be in clean rooms; we luxuriated in baths and clean garments. The Ogdens came over in the evening to visit and help us make plans. Miss Collier stayed with the Ogdens after turning Ossa, the Tibetan girl, over to Mrs. Sorensen.

The next morning our party assembled and was soon en route for the camp site, some thirty li beyond the town. Our road wound up the valley of the Lu River and crossed the bridge which is known as the "Gateway to Tibet." The site was beyond the summer palace of the King of Chala and near a small Tibetan village consisting of a few clustered houses. The sides of the narrow valley were covered with grass, flowers, and shrubs, with no large trees anywhere near. The general effect was like the high mountains in Colorado. Tibetan women walked off with our boxes on their heads or shoulders while their men looked on and nonchalantly rode their horses or gamboled about in a carefree manner. They did not have the curiosity that Chinese always show when any new person or thing enters their range of vision.

Mr. Ogden had rented Tibetan tents for us. Ours leaked: it was made habitable by the loan of a tent fly from the Ogdens. The sides of the tent were separate from the roof and could be raised or lowered to cool and ventilate the tent. Most of the tents were unlined, but ours, about ten by twelve feet, had a lining of figured Indian cotton. The design was printed in tans, browns, and soft reds on white; and the figures were Indian: turbaned, full-trousered people with leopards, elephants, and conventional flower forms. The camp had five sleeping tents and one with extending fly for kitchen and dining room. We four women took turns keeping house.

In the village we bought yak or dzo milk.[1] From the milk we made butter.

[1] The dzo is a yak-cow hybrid which serves most of the functions of the yak in areas, like Tatsienlu, that are slightly below the high altitude favored by the yak.

Every few days we sent a servant to Tatsienlu. He went down late in the afternoon so as to be there for early morning market on the following day. He was given inn money and was not to go to the foreigners in Tatsienlu unless we sent letters or messages. Food supplies were simple but we could get excellent yak (dzo ?) steaks, a limited variety of vegetables, and expensive eggs brought up from Waszekow. I am sorry to say that these were not always worth the care taken to get them a day's journey to Tatsienlu and then to us. Everyone insisted that hens would not thrive in Tatsienlu; hence the need to bring them up from down the road.

We named our camp "Chala" in honor of the district in which Tatsienlu is situated. Camp Chala was at an elevation of 10,500 feet and near the Lu River, from which we got our water. It was also not far from some hot sulphur springs.[2] One of the first days we were in camp our servants visited these springs and reported that the water was very hot and very cleansing. They evidently enjoyed a good soaking. Our men then had the coolies clean out the pool so it would be more attractive. We women ventured down there for baths, using a small pup tent as dressing room, and old clothes for bathing garments. The big thrill of our bathing was to follow the warm dip by a cold one in the nearby river. In these and similar hot springs, the Tibetans are reported to take an annual bath, getting in for a long soak and wearing their ordinary clothing. This takes the place of weekly ablutions and laundries for the whole year.

The steep sides of our valley blocked views of the snowy mountains on either side; but at the head of the valley there was a magnificent snow peak with a glacier on its flank. This glacier fed the Lu River, so it is no wonder that its water was like ice. In the clear mornings this peak was a fine sight and seemed very near. Also, in the early mornings there was often frost around our tents. The hardy wild flowers were not abashed by it and grew everywhere, even persisting inside our tents, where they stood under our cots and between the few planks which served in lieu of flooring.

We frequently went on rambles and picnics. The Tatsienlu friends came out to visit us now and then. And there were other occasional visitors. Among them were E. H. Wilson, the noted plant explorer; Mr. Zappey, a bird collector; Mr. Lowe, our Chinese-American mining engineer; and Captain Malcolm M'Neill, a big-game hunter. Once we met a French doctor and his wife who were evidently staying with the Catholics at their Tatsienlu mission. The men also spent a good deal of their time hunting. They shot pheasants and pigeons and kept us so well supplied with the latter that I vowed before the summer was over that I had eaten enough pigeon potpie to last a lifetime.

[2] when I passed this way with the Harrison Salisburys on our 1984 Long March, I thought the motor highway might be close to the site of Camp Chala. So I inquired for hot springs. I found that there are several in the area.

17

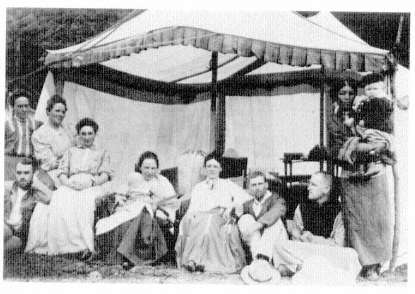

Enjoying life at Camp Chala. Grace is in the center. Bob, with his new-grown

beard, is on her left. On her right is Mrs. Sorenson from Tatsienlu, who was

visiting the camp that day with her children (one in her lap, a second held

by a Tibetan nurse at the far right).

The men made several excursions up to a glacial lake. They named it Lake Davidson in honor of E. J. Davidson of Chengtu, who had inspired our own trip by visiting the area the year before. On one occasion Bob and Harold Robertson had the coolies carry up a small tent and food. They spent the night at the lake and then climbed the next day to an elevation of 16,500 feet up the side of the high peak and onto the glacier. They arrived back at Camp Chala in the evening after their two-day trip just as a fierce storm struck us with rain, high wind, and a heavy fall of hail.[3]

[3] Bob and Grace both loved the mountains and were fervent environmentalists long before being one became so popular. This Tibetan summer was an experience that they often reminisced about. Grace's feeling for nature was rather philosophical. She was a John Muir enthusiast and had most of his books. For Bob the lure was more physical: the excitement and challenge of climbing, and the pleasure of exploration.

For exploration was, indeed, an important and ever-present element. At that time, all the mountain areas of West China and the Tibetan borderland were little known and very sketchily mapped. It was the heyday of plant explorers bringing home wonderful new varieties of flowers such as rhododendrons and camellias. Hunters came for ordinary things like bear and leopard and, more seriously, for Himalayan exotica such as the goral and the serow (genera of goat antelopes); an even greater rarity, the giant panda, was sometimes thought to be a myth (the first live specimen was not collected until the 1930s). It was natural for travelers in these regions to feel a kind of obligation to collect useful information. Note, for instance, Grace and Bob's carrying a boiling-point thermometer (technically, a hypsometer) to determine elevations (relying on the fact that the boiling point of water falls as the elevation rises). Bob started collecting butterflies as a hobby, but he also hoped to find new species.

Housekeeping chores kept the women busy for a good part of the day with preparing meals, giving out supplies, doing laundry, making butter, and such items. In the evenings we played games and almost always went early to bed. The night air grew quickly cool, and our lanterns did not give much light for festivities. The men did get m a good many chess games; I remember going to sleep with two chaps huddled over the chessboard in our tent.

While we were there m camp, Bob received word from the International Committee of the YMCA in New York that we were to buy land and build a residence in Chengtu. This excited and pleased us, and we spent quite a bit of our time thinking and talking about house plans. The International Committee later decided not to build for the time being; so our excitement was all in vain.

We visited the large, barrel-shaped prayer wheels set in a small stream near our camp and turned by waterwheels. We went to see a captured leopard at the summer palace of the King of Chala. We crossed the river and climbed the mountainside to inspect a leopard trap. And we had our own leopard scare one evening at dinner when the servants were alarmed by suspicious noises near the cooking tent. We closed the tents at night, but they were flimsy shelters. We often heard the trampling of dzo s as they grazed nearby, or their whoofs as they ambled off in the early morning. We woke early, for the sun on the roof of a tent was not conducive to lengthy sleep. Often there was Harry, still in his pyjamas and mounted on his horse (named Red), whooping us all up as he tore off for a dip in the hot spring. Jokes and friendly banter made camping jolly for all.[4]

Harry's mafu (horse coolie), named Lao Tsao, had some friends in Tatsienlu, presumably fellow horsemen. He liked a good time and complained that he was not getting enough money to give him appropriate "face." (The reason for his scarcity of money was that Harry was having a part of his wages paid to his wife and family back in Yachow.) One night there was a commotion among the servants; someone had come from the village, where the horse and his keeper were quartered, saying that Lao Tsao had tried to commit suicide. He first drank as much native wine as he could afford. He then tied his cloth turban around his neck as tightly as possible. (In Szechwan many men wear cloth turbans, especially horse coolies, load car-

[4] The people who shared this trip remained close friends, especially the Services and the Openshaws, who, to us boys, were much-loved Uncle Harry and Aunt Lona, more "real" than those other aunts and uncles in faraway America. When I remember her, Lona had become a comfortably ample, very "motherly" woman. Harry remained spare and full of energy, never silent for long, full of yarns and stories. He and Bob would keep up a steady flow of banter, joshing, and good-humored teasing wit that could entertain both foreigners and Chinese. If there was anyone who understood how to interest and amuse a young boy, it was Uncle Harry. Fate was not kind, for they never had children.

18

Harry and Lona Openshaw (about 1910). Yachow, where

Harry worked,was a small, frontier town. He wore Chinese

clothes because he found thempractical and comfortable,

but he did not follow the example of many of his fellow

missionaries in remote locations, who tried to reduce their

visibility with a queue.

riers, and other outdoor workers.) Harry rushed off to the village to see what could be done. Lao Tsao's throat stricture was removed, and he was revived and admonished—with the aid of some cash to restore his face as a servant of foreigners.

There were three high spots of the summer: a visit to the Dorje Drag Lamasery, a mile outside Tatsienlu, where we witnessed a Devil's Dance; a trip to Jedo Pass (for the men); and a picnic trip to the Moshimian Pass. We also went down to the King of Chala's summer palace to see the barley harvesting. The reaping was carried out by whole families who gathered to make the affair a regular festival. They erected booths to live in and seemingly had a good time at their work.

For the Devil's Dance, our Tatsienlu friends had made plans. We had fine seats on the veranda, or gallery, overlooking the courtyard where the dance

took place. The costumes were of rich materials in the brightest colors and in the most fantastic mariner, with much gold and silver thread, tassels, and jingling metal. Each lama performer wore a large head mask fitted in such a way that his eyes looked out through the mask's mouth. Thus the height of each performer was increased, which added greatly to the effect.

The dancers came out in groups, often dressed in similar style, and performed to the music of drums and long and short trumpets, with now and then a blast from a conch shell. The musicians sat at one side and made a picturesque appearance. The long trumpets were the most intriguing of the instruments,' being some eight feet in length and resting on props near their open ends. The dance movements were stately and resembled in some ways the dances of North American Indians. There were wizards and demons, goddesses and heroes, and kings with many attendants. Some wore human and some animal masks. Of the latter, the most important seemed to be a stag in imposing regalia.

The ignorance about the meaning and symbolism of this ceremony is surprising. It was hard for us to discover what was going on; even our Tibetan-speaking friends were not able to give us much help. Some years later I found an account of this same festival in this very lamasery. Those who are interested may read this fine description in A Tibetan on Tibet by G. A. Combe, a former British consul in China. Mr. Combe characterizes some of the climactic parts of the ceremony as "relics of the human sacrifices of pre-Buddhist days."

We were permitted to visit the shrines in the lamasery. In the main hall there was a considerable collection of brass butter lamps lit in honor of the festival. There were also butter images of some of their deities. We met Mr. Lowe, Captain M'Neill, and others at the Devil's Dance; as we had all brought food, we ate in picnic style together.

After the meal we met the King of Chala, then living in Tatsienlu and so shorn of any former power that he was chiefly tolerated as being useful in providing ula (a form of corvée to provide animal transport) for travel between Tatsienlu and Batang.[5] The king had two wives; as the first had not produced a child and the second had, he had elevated the latter to a position equal to that of Number One. The women of our party were taken to meet these two queens. Both were similarly dressed in long Manchu-like gowns of heavy dark-blue satin brocade, stiff with gold-thread Chinese characters, which looked like geometric figures on the rich background. Though their

[5] This Tibetan borderland was divided into many small hereditary states, which were treated by the Chinese as tributaries. The heads of the smaller units were called tusi ; chieftains of larger areas were given the Chinese title of wang (king). As Grace says, their power was much circumscribed (especially in a Chinese enclave such as the town of Tatsienlu); but the Chinese government had little direct contact with the rural Tibetans, finding it quite satisfactory to rule indirectly through these native princes.

garments looked Manchu, their heads were elaborately dressed in Tibetan style with braids and much silver, coral, and turquoise ornamentation.

We had not garbed ourselves for attendance on royalty. I was wearing a khaki suit with a Norfolk jacket and short skirt over riding trousers, high boots of tan leather (these always intrigued both Chinese and Tibetans!), and a soft white silk blouse fastened up the front with pearl buttons. The royal ladies had little conversation; the only thing I remember was a question directed to me by the Number One Queen. From the magnificence of her satin gown and heavily ornamented head, she inquired why I wore fish bones on my clothing. She had noticed that my buttons were of pearl ("fish bone") instead of precious metal.

In August, Harry, Harold, and Bob went off with Mr. Sorensen on a trip to Jedo Pass. This pass, some 15,000 feet in elevation, is several days "in" from Tatsienlu on the road to Litang, Batang, and finally Lhasa. The men were gone five days, and the Ogdens stayed with us women in Camp Chala while they were away.

On August 20 the Robertsons and Miss Collier left for Chengtu; the Openshaws and we had decided that we could stay on for another week. On one of our last days, we four went on a picnic to the Moshimian Pass. This was in the opposite direction from Jedo and gave onto the high levels of the Black Tent Tibetans. The altitude of this pass we found, by boiling our thermometer, to be 13,100 feet. Lona rode Harry's horse, and I went in my light mountain sedan chair carried by the men who had stayed with us all summer. It was hard for me to walk at 10,000 feet, and I had used a chair nearly every day. The day was fresh and bright, the air crystal clear, and we had transcendent views of the lofty snow peaks. Four big glaciers were all spread before us as though we could reach them in a short time. However, we knew the distances were deceptive.

We saw many rhododendron bushes and could look across the pass to forests below on the other side of the divide. There was a keen, chili wind, while the blazing sun burned us all and made our skins feel taut and fiery. During our return in the afternoon, the others had all gone ahead while my men were plugging slowly along with my chair. Suddenly there was a snort and a whoof as we were passing a marshy pond in a little meadow. Confronting us was a large, angry-looking dzo with lowered head and long, waving body hair like swinging skirts. The chair bearers began to falter, and the front man called out that they had better put down so all could run. That was the last thing I wanted, since the men could run and I would be left alone with the beast. So I told them not to set down. The old dzo came toward us in a threatening manner, but the men hustled as fast as they could and finally reached some bushes that took us out of the irate creature's sight. Dzo used to graze regularly around our camp; most of them were accustomed to

people and never showed any hostility. The long petticoat-like hair on their lower body and flanks gives them a strange look and makes them appear larger than they really are.

Bob went out several times with Mr. Ogden to hunt bear, but they were never successful.[6] His largest trophies were pheasant, grouse, and rabbit. One afternoon I saw a bear as I returned in my chair from a trip along a river path above our camp. The animal was across the river, busily gathering berries from bushes close to the water. It stood up and stuffed these into its mouth. We had both wild blackberries and strawberries close to camp.

On Thursday, August 26, we rose early, and I made butter in preparation for the travel ahead of us. We had laundry done. In the afternoon we were in our tent with clean things folded and lying around us on the two cots as we packed our road boxes. There was regularly a stiff breeze in the late afternoon, but that day the wind suddenly turned into a gale. Our old tent blew up and crashed down upon us. It was a great mix-up, but we finally were able to emerge to begin chasing our garments, many of which had blown out as the tent went down. Some caught on bushes; others flew farther afield. Our packing was at last accomplished, and we set up our cots in Miss Collier's former tent for our last night in camp.

Next morning, the fiftieth of our days in Camp Chala, Messrs. Sorerisen and Ogden and Captain M'Neill came out for noon dinner and to help us break camp. Lona Openshaw on Red (Harry's horse) and I in my chair set off for Tatsienlu, leaving the men to finish dismantling the camp.

[6] Bob never lost his zest for hiking and climbing, but he must have lost interest in hunting. He kept his rifle and shotgun, but in the years that I can remember they were almost never used. And I cannot recall that the possibility of my learning to shoot was ever even mentioned.