Three Contemporary Productions

The importance of Ramlila in Banarsi life has not been adequately conveyed in scholarly writings on the city. Hein mistakenly reported that the tradition was in decline, that the entire Manas was no longer performed at Ramnagar, and that the city as a whole mounted only three productions.[46] More recently, Eck, in her description of the city's festival cycle, mentioned only two productions and gave the impression that

[43] C. N. Singh, interview, October 1983; a description of Ramsvayamvar[*] is given in Singh, Rambhaktimem[*]rasik sampraday , 472.

[44] Hein cites a verse by the poet in praise of Ramlila; The Miracle Plays of Mathura , 99.>

[45] Awasthi, Ramlila , 88.

[46] Hein, The Miracle Plays of Mathura , 94.

participation in Ramlila was restricted to the Kshatriya community.[47] In fact, Ramlila is a flourishing and all-but-ubiquitous tradition in Banaras, enjoys the broadest patronage, and is represented by productions that are looked on as exemplary throughout North India. For although. other cities also boast old and famous productions, it is widely felt that the inhabitants of Banaras stage Ramlila with special flair and enthusiasm (dhum-dham ), and Banarsi productions are often highlighted in popular magazines at Ramlila time. The narrator of Premchand's short story "Ramlila," which concerns a small town production, observes, "The Banaras lila is world famous; they say people come from far and wide to see it."[48]

Although the Ramlila is particularly associated with the first ten days of the bright fortnight of Ashvin, not all Banaras productions fall within this period, and some do not occur during the month of Ashvin at all. The Ramnagar production begins its epic recitation on the third or fourth night of the bright half of Bhadon and has its final ceremony in the dark fortnight of Karttik, more than forty days later. Most other productions, which typically range from ten to thirty days, fall within this period, but a few do not. The lila on Panchganga Ghat, for example, does not even begin until after the Divali festival, a full fortnight after the conclusion of the Ramnagar pageant, and runs for another few weeks. Thus a dedicated lila -goer not only has a choice of numerous productions during the height of the season but can, in theory, attend a nightly performance of one or another cycle for close to three months. In 1982, on the night after the conclusion of the Ramnagar cycle, I chanced on a decorated stage in the middle of an intersection near my house. Surrounding streets were festooned with lights and lined with snack and souvenir vendors, and loudspeakers were blaring cinema music and advertisements. I soon learned that the Bharat Milap of the Khojwan Ramlila cycle, which runs on a different schedule from that of Ramnagar, was to occur later that night. When I returned to witness it I was promptly accosted by a betel seller who had been a regular at the Ramnagar plays; exclaiming delightedly, "Good! You've come too!" he added, "See brother, here in Kashi the Lord's lila goes on and on!"

Thus, it is more correct to speak of a Ramlila "season" than of a mere festival—a season that begins during the rainy month of Bhadon, runs through the transition month of Ashvin, and continues well into the

[47] Eck, Banaras, City of Light , 269.

[48] Premchand, "Ramlila," 55.

cool, autumnal month of Karttik. During this season, wooden platforms sprout like mushrooms at major crossroads and on many ghats. To a daytime visitor, these dilapidated structures hardly seem to warrant notice, but the same visitor returning at the proper hour of the night would see them transformed by rich draperies and backdrops into palaces and battlefields to be trodden by the feet of tiny gods in gilded and spangled costumes. In all, according to a recent tally, the city mounts some fifty-six annual productions, the majority of which are staged by the citizens of various neighborhoods, each of which has a local Ramlila committee. The financial arrangements are essentially as described by Hein for the Braj productions: a month or two before performances begin, the committee conducts a general collection (canda ) throughout the neighborhood, recording the amount given by each donor. Prosperous merchants may contribute substantial sums each year but, as Hein noted, a good portion of the typical pageant's budget comes from countless small donations, which make even some of the poorest citizens Ramlila patrons.[49]

The Ramlila is a small industry and supports a variety of peripheral enterprises: artisans who build effigies and create fireworks; tent houses that lend platforms, awnings, and lights; and shops that provide costumes, masks, and props. Several such establishments are located in the old brass bazaar in Thatheri Gali, and although these stores also outfit temple images and nautanki[*] troupes (another genre of folk theater), the heavy concentration of Hanuman, Ravan, and Shurpankha masks hanging from their rafters clearly advertises one of their main lines. Then there are the hawkers of lila -related toys and treats: toy bows and arrows, clay figurines of Hanuman, and small papier-mâché masks of the same design as those worn by players.

One sign of the popularity of Ramlila , and an indication that its productions attract audiences from outside their immediate localities, is the inclusion of daily schedules throughout the season in the city's Hindi newspapers. The most comprehensive listing appears on the "Banaras and Vicinity" page of Aj , the city's largest-circulation daily. The evening's program at Ramnagar is always given first, followed by that of Chitrakut—a sign of the high prestige of these two productions. Eight days before Dashahra in 1982, for example, the listings began as follows:

[49] Hein, The Miracle Plays of Mathura , 93-97.

Figure 22.

Ramlila masks and props at the headquarters of the Khojwan

Ramlila Committee (photo courtesy of William Donner)

Kashi's Ramlila

Tuesday, 11 October

Ramnagar: Interlude on Mount Subel

Chitrakut: Fight with Jayant

Mauniji: Severing of the Nose

Daranagar: Royal Consecration

Aurangabad: Shabari's Good Fortune

Gayghat: Slaying of Khar and Dushan

Nadesar: Burning of Lanka

Ardali Bazar: Killing of Bali

Khojwan: Meeting with Nishadh

Khajwi: Meeting with Hanuman

Lahtara: Sumant's Arrival

Ashapur: Abduction of Sita

Lallapura: Janak's Arrival[50]

[50] Aj , October 11, 1982, p. 3.

and so on through another forty listings. Besides highlighting the variety of episodes that might be viewed on any given night, such notices help readers keep track of the progress of various pageants, in anticipation of particular events they don't want to miss. Kumar notes that "there is a sort of consensus in every muhalla as to which lilas are of most importance, and which of middling and of low importance, and attendance conforms to this judgment."[51] Many otherwise undistinguished productions have one episode that enjoys citywide fame, such as the "Dhanush Yajna" of Laksa, the "Nakkatayya" of Chaitganj, or the "Dashami" of Chaukaghat. These attract thousands of spectators from all over the city, but each production follows its own schedule (and may even follow a different calendar, since local pandits sometimes disagree on the timing of important lunar dates), and so the newspaper listing, based on the schedules printed by each committee, is a convenient reference.

Chitrakut and the Bharat Milap

The Chitrakut Ramlila Committee is headquartered in a walled garden adjacent to the Bare Ganesh Temple in Lohatiya, the old iron bazaar, and its production is staged there and at six other locations in the northern part of Banaras—the area sometimes referred to as Kasikhand[*] and thought to represent the more ancient part of the city. "Chitrakut" is the name of a pilgrimage place on the Madhya Pradesh border where Ram is supposed to have passed much of his forest exile; it is also the name of a locality that is the site of several performances in this cycle, although it seems probable that, here as elsewhere, the locality's name derives from the play rather than vice versa.[52] As already noted, this production is widely regarded as the city's oldest and (with Ramnagar) most distinguished Ramlila . But whereas Ramnagar is famous for the whole of its thirty-one days, the twenty-one-day Chitrakut cycle enjoys its fame primarily for a single lila : the Bharat Milap ("Reunion with Bharat," reenacting Ram's triumphant return to Ayodhya and meeting with his faithful brother), which occurs on the seventeenth day of the cycle in a locality known as Nati Imli.

Two legends about the Chitrakut pageant are often cited by Banarsis to explain its popularity. The first is the story, already referred to, of its founding by Megha Bhagat and of Ram's promise that he himself would

[51] Kumar, "Popular Culture in Urban India," 279 n. 45.

[52] Hein points out that the legends of the founding of this lila appear to conflate Megha Bhagat with Tulsi himself, who reputedly had a vision of Ram and Lakshman at Chitrakut; The Miracle Plays of Mathura , 106-7.

be physically present on certain days. Some say that he promised to be present on eight days, others claim six, and still others four. All agree, however, concerning the Lord's presence at the Bharat Milap, at which Megha Bhagat is said to have had the supreme vision and surrendered his body.

The second story concerns a nineteenth-century Hanuman player who was mocked by an Englishman—in some versions, by the district collector, who brought a party of "English ladies and gentlemen" to view the native spectacle; in others, by a "Padre MacPherson" who criticized the performance as part of his attack on Hindu customs.[53] It is said that the day's lila depicted Hanuman's mission to Lanka and was held on the bank of the Varuna, the Ganga tributary that marks the city's northern limit. The Englishman, who had some knowledge of the Ramayan, mocked the religious pretensions of the play: "You say these are gods, but really they are only actors. The real Hanuman leapt across the sea; yours couldn't even cross this small river!" Accepting this challenge, the offended actor bowed before the child portraying Ram, who presented him with his ring—just as the real Ram did before dispatching Hanuman to Lanka. Then, fastening on his heavy brass mask, he strode to the edge of the Varuna—whose stream is some eighty feet wide—and attempted the impossible leap. To the astonishment of all, he succeeded, but fell down dead on the other shore. The foreigners' mockery was silenced—some versions claim that the collector officially announced that henceforth this production alone was to be regarded as the "true" Ramlila —and the actor's mask and costume were enshrined in a samadhi at the Chitrakut lila site, where they are still worshiped each year by the current Hanuman, his descendant.[54] This popular story suggests the distinction drawn by devotees between a dramatic performance and a true lila : the former is only a representation, but the latter is a realization. It also suggests the paradoxical relationship—central to Ramlila —of the player to his role. The hero is an ordinary man who is challenged to perform a superhuman feat and does so at the cost of his

[53] Awasthi's sources give the year as 1868 and identify the player as a Brahman named Gangaram Bhatt, whose descendants are still said to play Hanuman; Ramlila , 62. Mehta gives the actor's name as Tekram; "Udit udaygiri," pt. 1, p. 43. Barr's informants assign the incident to 1803; "The Disco and the Darshan," 11.

[54] One hears various explanations for the player's demise. Some say the svarup when blessing him had ordered him not to look back, and that disobedience cost him his life. An elderly silk merchant gave me a different interpretation: "When he reached the other bank, the thought 'I did it!' entered his heart, and with it the shadow of self-pride. That was intolerable to Hanuman-ji, and so he expired." Baldevdas, interview, October 1983.

life; yet the legend implies that he is able to succeed precisely because he is not, at that moment, an ordinary man. He becomes his role and "crosses over" in more ways than one.

The Chitrakut cycle begins each year on the ninth or tenth of the dark fortnight of Ashvin, some ten days after the start of the Ramnagar plays. As noted earlier, the Brahman boys chosen to be svarups are unusually young; Ram in 1983 was only nine, Lakshman and Sita a year or two younger, and the other brothers younger still. The adult characters—Hanuman, Vibhishan, Ravan, and the rest—are played by the same men year after year, and the roles are passed down in their families.

Bharat Milap

In terms of attendance, the Nati Imli Bharat Milap is probably the single biggest event in Banaras's annual festival cycle. In 1983 the superintendent of police estimated the crowd at 500,000 persons—nearly half the population of the city.[55] This astonishing participation is not a recent phenomenon; the scale of the event in the late nineteenth century is suggested by a report in the Aj of October 30, 1893, which remarked of the Milap, "It would have to be an invalid or disabled person who does not go to see it."[56] Notices often appear in the press for reserved places on adjoining housetops; there are also "Bharat Milap clubs," which rent whole roofs. Many businesses close for the day, and from early morning all roads leading into the northern half of the city are closed to vehicular traffic to facilitate the flow of crowds into the Milap area. By midday it is all but impossible to get anywhere near the site without a special guest badge from the Ramlila committee—and these are so parsimoniously distributed that one might suppose they were tickets to paradise.

The site of the Milap is a rectangular field containing a huge tamarind tree (imli ) from which the area takes its name. At each end of the field are stone platforms, connected by a slightly raised runway perhaps a hundred yards long. Each year the platforms are freshly whitewashed, the maidan is cleaned, and a processional path of crushed red stone is laid for the maharaja of Banaras and his retinue, who will approach from one of the side streets. Crowd control arrangements are particularly impressive: a bamboo barricade some fifteen feet high is erected

[55] The estimate was made by the superintendent, Shrinath Mishra (no relation to the famous expounder of the same name), in the course of an interview with Linda Hess, to whom I am grateful for this information.

[56] Cited by Kumar, The Artisans of Banaras , 198.

wherever the field fronts on a street, and the inside of the barrier is lined. by hundreds of policemen; this is to prevent a crush from the densely packed crowd, which fills surrounding streets for blocks in every direction. A police command post on the roof of an adjacent building also serves as a reception center for dignitaries and boasts a colored awning, carpets and chairs, and a booth for All-India Radio, which broadcasts live coverage of the event. Loudspeakers on nearby houses carry announcements of lost children, although all sound is tastefully hushed as the great moment approaches. The impressive discipline and clockwork timing suggest a state ceremony or the opening of the Olympic Games, yet the remarkable thing about the Milap in comparison with such events is that all the elaborate arrangements serve to bracket a performance that lasts roughly four minutes. The incongruity of this is not lost on Banarsis, who appear to take special delight in it. "The whole thing is over in the blink of an eye," one man remarked to me, "yet hundreds of thousands flock to see it, and you must go too!"

The protocol of the Milap allows for the participation of several of the city's traditional communities. On the eve of the great day, a palanquin bearing Ram and his companions is carried from Chauka Ghat (representing Lanka) to the Chitrakut enclosure (representing the Nishadh's ashram, where Ram rests for the night). The enormous wooden palanquin, brilliantly painted in designs of flowers, birds, and animals, represents the flying chariot (puspak[*]viman ) of Ravan, now utilized by the victorious Ram, and is carried by members of the merchant community, who believe that this service insures their commercial success during the year.[57] On Milap day itself, the same task is performed by 125 members of the Ahir, or milkman, caste, who dress in white and tie on red turbans symbolizing their resolve (sankalp[*] ) to carry the Lord's vehicle.[58] They assemble outside the Chitrakut enclosure, within which the boy actors are being costumed, and worship the palanquin before lifting it. Not least among the privileges that their act of service confers is admittance to the cordoned-off inner field, from which they can obtain a clear view of the climactic embrace.

Another class of functionaries are the "beautifiers" (srngariya[*] ), who supervise the costuming and makeup of the actors. These men represent a community of Gujarati silk merchants that has lived in Banaras for some five centuries. They are recognizable by distinctive turbans of

[57] Awasthi, Ramlila , 63.

[58] Barr, "The Disco and the Darshan," 10; Barr notes the intense competition for the 125 turbans, which are distributed by the organizers.

gold-brocaded purple silk; they claim that the privilege of wearing this headgear on state occasions was granted them by Emperor Akbar in appreciation for silk they provided to the Mughal court. Their prosperous community carefully maintains its ethnic identity even while it occupies a prestigious niche in its adopted city. Its members speak Hindi outside the home, but Gujarati within it—a remarkable continuity in view of the fact that, as some of the men told me, they have never been to Gujarat and have long ceased to have relatives there. Notable too is the fact that the srngariyas[*] all belong to the Pushti Marg sect, founded by Vallabhacharya, and worship Krishna as the supreme deity. Pushti Marg theology maintains the absolute supremacy of the Krishna avatar and regards Ram as only a partial manifestation; the merchants' greeting among themselves is "Jay Sri Krsna[*] !" which contrasts with the more typical Banarsi "Ram Ram" or "Jay Sita-Ram!" In Vallabhite temples special emphasis is given to the elaborate adornment (srngar[*] ) of images, which varies with the season and time of day, and the devotee charged with these arrangements is likewise known as a srngariya[*] . In Banaras, even though Krishna is not without his adherents, the silk merchants have adapted themselves to the predominant Vaishnava strain of Ram bhakti by assuming the role of costumers in this prestigious Ramlila .[59]

It was one of the srngariyas[*] , with whom I had chatted briefly while the actors were being made up, who secured my entry to the inner field at Nati Imli on Bharat Milap day in 1983—for the soldiers guarding the bamboo gate, nervous at the press of the enormous crowd outside, had ceased honoring even guest badges by the time I arrived at the enclosure. Once inside, I made my way to the vicinity of the main platform, where I found myself surrounded by prominent Ram devotees and patrons, all dressed in their finest clothes. Also present were the twenty-four Ramayanis, identifiable by broad sashes of ocher satin, who would chant from the Manas during the performance. The gleaming white platform was encircled by purple-turbaned srngariyas[*] , each equipped with a basket of flower petals.

The hour fixed for the Milap is always observed with great punctiliousness. Mehta has noted that early evening in this season is a time of special beauty, which seems to contribute to the extraordinary and otherworldly atmosphere.[60] In 1983 the appointed hour was 4:45 P.M. , and

[59] Such a catholic adaptation was encouraged by the example of Tulsidas himself, who is said to have resided for a time near the Gopalji Temple and to have felt special devotion for its resident deity; note his authorship of the Krsna[*]gitavali .

[60] Mehta, personal communication to Kumar; The Artisans of Banaras , 198-99.

as afternoon shadows lengthened, a flood of golden light filled the enclosure and the atmosphere of joyous anticipation became unmistakable and infectious. At about 4:30 a slowly swelling roar in the distance informed us that the palanquin had left the Chitrakut enclosure, and we strained to catch a first glimpse of it beyond the tall barricades, the massed ranks of policemen, and the sea of upturned faces. First to appear was a smaller palanquin bearing Vibhishan, the newly crowned king of Lanka. A whimsical-looking man with a long gray beard and ash-white makeup, accompanied by several small children, Vibhishan was carried to a spot close to the main platform as an honored guest. The cheer of the crowd swelled to engulf the whole square as the great viman itself came into view, seemingly borne on a flood tide of bobbing red turbans (popular lore holds that it can actually be seen to float above the milkmen's shoulders). In slow majesty it entered the field and came to rest on the farther of the linked platforms. No sooner had the cheer greeting its arrival died down than another became audible from the opposite side of the enclosure, gradually growing into a thundering chant of "Har, Har Mahadev!" and signaling the approach of the maharaja. The sight of the royal elephant, resplendent in its trappings of velvet and gold, set off another wave of cheering. Vibhuti Narayan Singh, wearing a jeweled turban and shaded by a white silk umbrella, acknowledged the crowd's greeting with a raised namaskar and rode across the length of the enclosure to circumambulate Ram's palanquin.

In the meantime, Bharat and Shatrughna had also arrived and had ascended the nearer platform. Everyone was now in place, and as the magic moment approached, the dead Lash of a great expectancy fell over the multitude. At the far end of the field, Ram and Lakshman descended from their palanquin and stood at the edge of the runway; simultaneously Bharat and Shatrughna prostrated themselves full-out on their platform. A clash of cymbals announced the presence of the Ramayanis, who began singing Tulsi's description of the scene in the familiar chant special to Ramlila . So perfectly synchronized and dramatically effective was the timing that it seemed as if an invisible clock, of which all were aware, was counting off the few remaining seconds, bringing every onlooker to a calculated emotional peak. With measured steps Ram and Lakshman began walking along the runway, but they soon broke into a trot, which gradually increased to a full run. The mass silence was replaced by a kind of involuntary and ecstatic roar, as when a crowd at a sporting event anticipates the imminent completion of a brilliant play. An instant later, the runners reached their destination and sprinted up the stone steps, where each lifted up one of the prostrate

figures and embraced him. A cloud of red and white blossoms, thrown in handfuls by the men ringing the platform, fluttered down over the embracing boys. Loud as the cheering had been, a great sound seemed to explode above it: a mixed cacophony of bells, gongs, conches, and roars of "Raja Ramcandra ki jay!" A moment later the boys realigned themselves for a second embrace, Ram with Shatrughna and Bharat with Lakshman, more cheering and more flowers. Then they formed a line, arms around one another's waist, and faced straight ahead, bestowing their much-desired darsan on the crowd facing the platform; then rotated forty-five degrees and again paused; and so on, through two complete rounds of the eight directions, each pause accompanied by an acknowledging roar from the appropriate sector.

And then it was over. The boys descended and walked to the waiting palanquin, which was soon hoisted on the shoulders of the Ahirs to proceed in slow procession to the committee's headquarters, giving darsan to tens of thousands more en route. The royal elephant departed for a rendezvous with a waiting limousine, which would speed the maharaja back to Ramnagar to supervise the delayed start of his own Ramlila . For the rest of the multitude at Nati Imli, there was little to do but stand and wait; it would be nearly an hour before the approach roads cleared enough to allow the square's human tide to flow back into the rest of the city.

The Nati Imli Bharat Milap was one of the most powerful dramatic events I had ever witnessed. Yet, as my Banarsi friends had promised, the "performance" lasted only a few moments, involved not a word of dialogue, and hinged on a single, elemental gesture. Awasthi has remarked that its extraordinary effect on spectators serves to remind us that the real power of "pantomimic lila " lies in its jhanki , or tableau.[61] It may be added that at Nati Imli there are additional factors at work: the powerful religious expectation, supported by the story of Ram's promise of physical presence on this day; the beauty and auspiciousness of the hour; the impressive, orderly arrangements; and the presence of the maharaja, who represents not only royal authority but also Shiva, patron deity of Banaras, and whose attendance is an affirmation of the city's cultural identity. There is a further sociocultural dimension too—for one may well ask why, of all the emotional events that follow the death of Ravan, the reunion with Bharat alone evokes such an ecstatic response. I return to this topic in my final chapter.

[61] Awasthi, Ramlila , 63.

The Enthronement

Two days after Bharat Milap I attended the performance of Ram's enthronement (rajgaddi ) in the garden compound at Lohatiya. The atmosphere could hardly have been more different from that of the frenetic and spectacular Milap. The same little boys who, two days before, had been the focus of the straining eyes of a vast multitude now sat casually on an open-air stage in a small garden, surrounded by the organizers and a handful of adult actors. And even though this performance too had been announced in the newspapers and no effort was made to exclude anyone, the total attendance during the course of the evening cannot have amounted to more than a few hundred persons. Indeed, the atmosphere was so casual that I felt I was witnessing a private party staged by the organizers for their own amusement. The child actors were in full costume—gorgeous silk robes and crowns for this special night—but they hardly seemed to be in "character"; much of the time they were lounging idly on the dais or playfully chatting among themselves, seemingly oblivious of the activities of the adults. The latter were in high spirits; everyone seemed to know everyone else, and the atmosphere suggested a backstage party after a successful opening night. Yet this was neither a party nor a rehearsal, but an actual performance of the lila of Ram's enthronement. What was one to make of it?

Amid the casual ambience, the expected sequence of events did unfold, after a fashion. The chief Ramayani, Pandit Bholanath Upadhyay, invited Ram to come sit with him near a small fire altar, where they were joined by several other Brahmans. The Manas passage describing the royal consecration was sung, and then the Brahmans began chanting Vedic mantras while their leader, smiling broadly, showed Ram what to do, guiding his little hand as he spooned oblations into the fire at appropriate intervals. While the ritual proceeded, the "party" continued all around. Vibhishan lounged at one end of the dais, conversing with an elderly devotee. Bharat and Sita played guessing games, periodically dissolving into giggles; Shatrughna fell asleep. Other groups of people sat in the garden chatting and paying no attention to what was going on. Throughout most of the evening (the ceremony began after 9:00 P.M. and continued for several hours) there were, with the exception of myself, no spectators; there were only participants, either in the lila itself or in the "party" that surrounded it. As the evening wore on, I found myself increasingly puzzled by the nature of the performance I was witnessing. It seemed inconceivable that the chuckling adult participants in the fire

ceremony, much less the inattentive onlookers, actually believed that the little boys were really the divine characters of the Ramayan. Was any "willing suspension of disbelief" possible in such a casual, even chaotic atmosphere?

But when the fire ritual concluded, an interesting thing happened. Upadhyay took Ram by the hand and led him to the marble throne platform at one end of the open-air stage. Sita, Lakshman, and Bharat followed; even little Shatrughna was roused from his nap and escorted over. The red-suited Hanuman donned his enormous brass mask and stepped forward, fly whisk in hand; a glittering silk umbrella was unfurled. Suddenly everyone in the garden was attentive. A tableau had taken shape: Ramchandra was enthroned in glory, Sita at his side, in the midst of his beloved brothers and companions. It was the climactic vision of the Manas , like Tulsi's own reputed first lila ; the nearly full moon of Sharad rode in the sky overhead. The Ramayanis took their places before the dais and intoned a hymn of praise from the Gitavali , and a steady stream of neighborhood people began to file through the garden gate for darsan .

Another performance followed: a long red carpet was unrolled at the foot of the throne, and Upadhyay stood to one side of it. The adult characters in the lila —Hanuman, Sugriv, Vibhishan, and the others—formed a queue at the far end. While "Ram" lounged casually on the throne, looking boyishly amused, the chief Ramayani addressed him in the reverent and formal language of a royal minister: "Divine Majesty, King of Kings, Lord Ramchandra!" He then began presenting each player to him with a brief introduction that was both reverent and, apparently, intentionally amusing:

Your Majesty, here before you is Sugriv. You know, Lord, he is a great devotee of yours, and he has done an awful lot for you. He bit off the nose and ears of Kumbhakarna, you'll recall. [laughter from onlookers] He attacked Meghnad too, and Ravan as well, and altogether he has suffered a lot on your account! Please be merciful, and bestow your grace on him.

While this patter was delivered, the player in question executed a series of seven full-body prostrations, beginning at the far end of the carpet and ending at the foot of the throne. These were accompanied by many chuckles of amusement from onlookers, both at the mock-seriousness of the introductions and at the difficulty with which some of the players—older men in elaborate, constraining costumes and heavy masks—executed their bows. These were anything but casual, however; each pros-

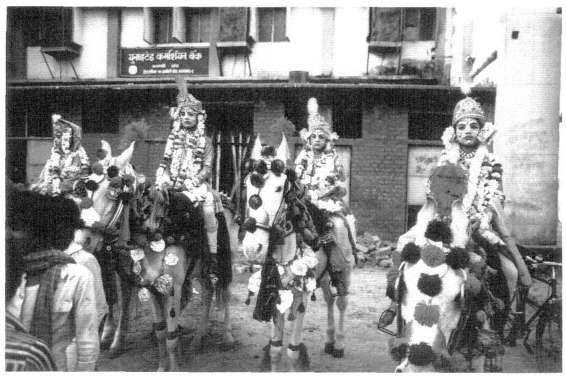

Figure 23.

A procession of boys adorned as Ramlila svarups

tration, achieved with no little huffing and puffing, was total. The man lay flat-out, arms extended toward the throne. Arriving at its foot, each player knelt and removed his mask, revealing a forehead beaded with sweat but a face grave and composed. His reward was forthcoming: the little Ram leaned forward and dropped a garland around his neck.

Reflecting on the evening's performance—on what seemed to me its incongruous conflation of high emotion and low comedy, casual ambience and occasional ritual intensity—I recalled a line from one of Hess's writings on Ramlila and its devotees: "people who grew up in easy intimacy with the God of personality and paraphernalia, the God who has characteristics like their uncles and cousins and is often as common and unheeded a household item."[62] The evening's experience had clarified a point often made by lila aficionados: that the little boys in gilded tiaras really are both children and gods. They are assumed to be guileless and innocent, free of the worries and compulsions of adults. Yet they are not merely blank screens on which devotees project the God of their imaginations; "attributes" are of the essence here, and the ones that the boys possess—innocence, physical attractiveness, Brahman-hood (equated with both social and religious prestige)—are essential ingredients in what they become. The boy chosen as a svarup is like the unblemished nim tree that the woodcarvers of Puri select, once every twelve to nineteen years, for their new image of Jagannath, Lord of the World.[63] Just as the Jagannath devotee may be aware that the image he adores was once a tree, so the Chitrakut spectator may recall, at times, that the boy beneath the crown is so-and-so's son, lives in such-and-such lane, and so forth. At the same time this boy possesses, by virtue of his attributes, the authority (adhikar ) not merely to represent but to become Ramchandra, just as the right kind of tree becomes Jagannath. And having become the part, he can offer something that every devotee craves and even temple images cannot bestow as tangibly: familiarity and intimacy with God; the chance to do seva ("service," connoting both formal worship and actual physical attention) and to experience "participation," which is one of the truest translations of the word bhakti . Each episode of the Chitrakut Ramlila affords a different kind of participation: the mass participation of the Milap, when the lila expands to incorporate the whole city and the auspicious paradigm of the

[62] Hess, "Ram Lila: The Audience Experience," 185.

[63] On the recreation of the Jagannath deities, see Tripathi, "Navakalesvara."

reunited brothers reaffirms familial and social hierarchies; and the intimate participation of the smaller performances, when large public symbols are replaced by near-private intimacies and grownup devotees play house with a child God.

Khojwan: Ramnagar Remade

The Ramlila of Khojwan Bazaar, a neighborhood on the southwestern outskirts of Banaras, makes claim neither to antiquity nor to originality.[64] When the current production was organized, around the beginning of the twentieth century, Khojwan was a little kasba (market town) well beyond the southern boundary of the city. Today spreading urbanization has engulfed it, but Khojwan's narrow, meandering main street, fronted by high stone buildings, strikes a contrast to the grid-patterned colonies that have sprung up around it. Every muhalla of Banaras nurtures its own sense of identity, but Khojwan's seems particularly strong. The tidy streets, flourishing bazaar, and new secondary school all bespeak municipal pride, and this is equally in evidence in the local Ramlila arrangements.

The printed announcement of this lila is the most elaborate that I have encountered. Its heading reads "Historic Ramlila of Khojwan Bazaar, Kashi," and this is followed by a paragraph summarizing the pageant's short history:

It is well known that the acts of Ram composed by Goswami Tulsidas are performed in Khojwan Bazaar for the benefit of devotees. In olden times, revered Mahatma Apadas-ji sponsored it for some days at Manasarovar, Sonarpura, Kedareshvar, and so forth; after that the late Gokul Sahu-ji, on the Mahatma's departing for heaven, with the assistance of the late Kashinath Sahu and Jagganath Sahu (the grain dealer), sponsored it in Khojwan Bazaar and for his whole life dedicated himself to it, body, mind, and fortune. Now that he has departed the world, this great work has been accomplished for sixty-six years with the will of the community and the assistance of devotees.,[65]

In her discussion of the patronage of neighborhood Ramlila productions, Kumar notes that organizers tend to fall into two categories:

[64] The spelling is a common romanization of khojvam[*] . I am grateful to Diane Coccari, who did extensive fieldwork in Khojwan, for having first suggested the local Ramlila as deserving of research. See her study, "The Bir Babas of Banaras."

[65] Khojwan Ramlila Committee circular, 1983. The term that I have translated "historic" is pracin (ancient), which is routinely used in Banaras for anything older than a decade or two, and seems to connote more a sense of accepted tradition than chronological age.

(1) middle-level merchants and traders in grain, wood, metal, or cloth as well as small shopkeepers, including those of milk and pan , and (2) religious figures, whether "official" (mahant or panda[*] ) or "nonofficial" (vyas , sadhu , baba ). The former would control money through his institution; the latter would attract it through his personality. As a rule, the people of categories (1) and (2) work in association.[66]

In its origin and organization, the Khojwan lila conforms to this model. The inspiration originally came from a Vaishnava sadhu who started a series of performances at sites in surrounding communities; the locations mentioned—the great tank called Manasarovar (after the Himalayan lake of Tulsi's allegory) and the bazaar at Sonarpura, about two kilometers northeast of Khojwan—are still used for certain performances. The sadhu's efforts were carried on by a group of traders in the bazaar; "Sahu" is the name of a mercantile caste, and there are still a number of Sahus among the forty-one officers of the Ramlila committee prominently listed on the schedule. The reference to the pageant's being conducted "with the will" of the community (pancayatajnanusar ) indicates that the source of its funding is a general solicitation. It was thus, I was told by committee members, that the 1983 production costs of approximately Rs 35,000 were met: "Some people give four or eight rupees, some give fifty-one, some give three hundred or more, according to their means." The announcement states that the lila has been organized in this fashion for sixty-six years—that is, since 1917, although it also indicates that Mahatma Apadas started his performances somewhat earlier.[67]

Today the Khojwan Ramlila enjoys the status of a venerable community institution and major investments in the pageant have recently been made. In the heart of the bazaar, just behind the popular Puran Das Temple, stands a handsome two-story structure with an open-air stage at ground level and a suite of rooms above. This tidy, brightly painted Sri Ramlila Srngar[*] Bhavan ("Ramlila Production Center," as an inscription on the facade announces) serves as committee headquarters; its upper rooms contain trunks of costumes and props, and their walls are hung with masks. Also kept there are the oversize copies of the Manas from which the Ramayanis chant and the script-books used by actors. These were composed by a local resident when the pageant first began

[66] Kumar, The Artisans of Banaras , 185.

[67] Barr was told that the lila was started in c. 1885 under the patronage of the maharaja of Vijayanagar, whose Banaras residence is located in Bhelupura, roughly midway between Khojwan and the river. Later, the pageant moved westward and its patronage shifted from royal to mercantile; "The Disco and the Darshan," 27.

and have recently been recopied and painstakingly illuminated by an amateur artist, a cloth merchant who, like the sari dealers at Chitrakut, also serves as makeup master. The beauty and exuberance of this man's work—some of his paintings also decorate the inner walls of the building—epitomize the enthusiasm and flair with which the burghers of Khojwan mount their lila ; appropriately enough, the artist's name is Shobhanath (Lord of beauty).

The stage on the lower level fronts on a large field that serves as the schoolyard for the local secondary school, in which the pageant's director is a teacher. In the lila , the stage and the field represent Ayodhya, which thus, as at Ramnagar, is situated in the heart of the community. Other sites—gardens, enclosures, tanks, and small stages—are scattered throughout the area, and participants sometimes trek several kilometers in the course of an evening. Many sites feature permanent structures built especially for Ramlila . One of the most impressive is located at the end of Khojwan's main street: a lofty pavilion with polished columns, resembling a permanent reviewing stand. This edifice represents Ram's abode in Panchvati, from which Sita is abducted by Ravan; it is used for the performance known as Nakkatayya (nakkataiya[*] ), which is described below. Apart from such specially built settings, existing sites in the area have also been incorporated into the drama; thus the large tank known as Manasarovar is used to stage the "Crossing of the Ganga" episode. When Ram alights on its further shore, he is received by the inmates of an adjacent Ramanandi ashram, who become (in the play) the denizens of the sage Bharadvaj's hermitage at Prayag.

The scale and permanence of the lila structures at Khojwan are striking—many community productions manage with makeshift platforms that are hauled about and rearranged to suggest the various sites—and their obvious model is Ramnagar, which lies across the river to the east. Yet the manner in which the prestigious royal pageant is recreated in Khojwan indicates the shift from princely to mercantile patronage that occurred at the close of the nineteenth century, which I noted in my discussion of Katha . The Ramnagar pageant, like the older style of privately endowed Katha , begins in late afternoon, and all but a few of its performances conclude by 9:00 or 10:00 at night. The timing serves the convenience of the royal patron, who schedules a long intermission after less than a hour of performance, during which he retires for his evening prayers—a procedure that, as Schechner has noted, daily advertises the maharaja's punctilious piety.[68] The Khojwan lila , on the other hand,

[68] Schechner, Performative Circumstances , 262.

like modern Katha festivals, never gets under way before 9:00 P.M., when the bazaar closes for the night. This has the result, given the leisurely pace at which most performances unfold, of setting many important scenes at 2:00 or 3:00 A.M. —a fact that organizers and players seem to take, for a month at least, in bleary-eyed stride.

At Khojwan a group of enthusiastic devotees backed by a prosperous business community have taken Maharaja Udit Narayan's inspiration one step further. Unable to go to Ramnagar regularly, they have brought Ramnagar home by reshaping their community to conform to the epic's geography, thereby also making a successful bid for wider recognition within the city. Khojwan was one of the handful of names commonly cited when I asked Banarsis to identify the most notable productions in the metropolitan area, and its biggest event, the Nakkatayya, ranks among the half-dozen or so top crowd-drawing lilas in the city. Such prominence suggests that Ramlila can serve as an effective vehicle for community identity and pride.

Although the Khojwan lila has drawn inspiration from Ramnagar, the imitation has not been slavish. While attempting to match the royal pageant's layout and scale, the local people have made innovations in specific details, which mark the lila as their own. At thirty-one days, it is fully as long as the maharaja's production, but it begins and ends about a week later and its choice of episodes for enactment is notably different. In his description of Ramlila in the Braj area, Hein noted a tendency among contemporary productions to stage and recite less of the Manas , which he ascribed to the increasing obscurity of Tulsi's sixteenth-century dialect.[69] The relatively new Khojwan production, however, displays an impressive degree of fidelity to its text and in fact dramatizes even more of the Manas than the Ramnagar pageant does. The Khojwan lila does not confine its staging to Tulsi's central narrative but begins early in Book One with the story of Sati's delusion, the courtship and marriage of Shiva and Parvati, Narad's infatuation (a crowd-pleasing comedy that is included in many neighborhood productions), and other episodes prefixed by Tulsi to his main story. It devotes six nights to these preliminaries, which precede even the birth of Ravan and the gods' plea to Vishnu to incarnate himself—the episodes with which the Ramnagar cycle begins.

In its staging conventions too, the Khojwan lila closely follows the epic text. At Ramnagar when dialogue occurs in the poem, the Ramayanis chant a character's speech in its entirety and then stop while the

[69] Hein, The Miracle Plays of Mathura , 275.

actor gives a prose paraphrase of the passage. At Khojwan long speeches are broken up into shorter units roughly corresponding to sentences; the resulting frequent alternation between chanting Ramayanis and declaiming actors creates the effect of a line-by-line prose commentary. In addition, the couplets that regularly occur within speeches (which at Ramnagar are rendered into prose) are often left untranslated at Khojwan; the actors interrupt their prose declamations to sing these couplets with great emotion, repeating what the Ramayanis have just chanted.

Another Khojwan innovation is a buffoon character reminiscent of the vidusaka[*] of classical Sanskrit drama. He is played by a gifted local actor and is brought into virtually every scene: as a courtier of Ayodhya or Janakpur, the boatman Kevat, and even Ravan when the latter comes disguised as an ascetic to abduct Sita. His special function is to supplement the written script with droll ad-libs delivered with a perfect deadpan expression. Other entertainment also finds its way into the production: there are interludes of lascivious disco-style dancing by female impersonators (hijra[*] ) on the occasion of Ram's birth and marriage. Here the producers are not simply pandering to popular taste but are following the time-honored practice of envisioning the events of the epic in their own familiar vocabulary—for hijras[*] do indeed gather, as they have for centuries, to dance and to sing obscene songs outside homes in which a son has been born or a marriage is about to occur.

Kop Bhavan

Like other Ramlila cycles, the Khojwan production includes both "little" and "big" nights. An example of the former is the episode known as Kop Bhavan (The Sulking Chamber)—the name popularly given to the scene in which Queen Kaikeyi, swayed by her maid Manthara's arguments, demands two boons from King Dashrath, thus precipitating Ram's exile from Ayodhya. At Khojwan this episode is not staged until the fourteenth night—nearly halfway through the cycle. This seemingly delayed beginning Of the central narrative results from the many evenings devoted to introductory stories and an extended treatment of Ram's marriage, which occupies three nights. Such a seemingly disproportionate emphasis on the early portions of the epic is a reflection both of Tulsi's own handling of the story and of the devotional inclinations of later generations of devotees.[70]

[70] See Chapter 5, Ramlila and Devotional Practice.

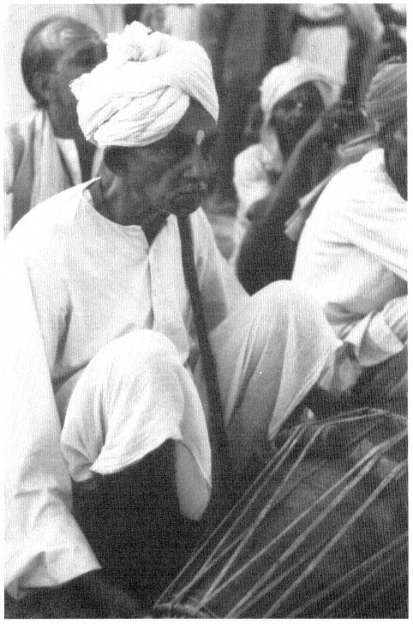

Figure 24.

The Kop Bhavan lila at Khojwan

The setting is the royal palace at Ayodhya, which includes the ground-floor stage of the Ramlila Center and the large field fronting it. On this field two small pavilions are erected, connected to the main stage by walkways forming a large rectangle. The pavilions represent various locales within the palace and city; a platform that represents the home of the royal priest Vasishtha later becomes the apartment of Queen Sumitra and the scene of her emotional conversation with Lakshman before his departure for the forest. Another platform in the center of the rectangle is occupied by the Ramayanis, who sit in a circle around a low table bearing two big copies of the Manas . The remaining space within the rectangle is filled by the audience, which also extends into the field beyond (see figure 24).

The crowd is of modest size—perhaps 250 persons—when the performance begins at 9:00 P.M. , but it grows steadily as the night proceeds. Although there are no designated seating areas, men and women instinctively gravitate to opposite sides of the enclosure, as they do at most religious programs. Floodlights mounted on the walls of adjacent buildings provide illumination. No amplification is needed in the semi-en-closed area; on nights when the pageant occurs in more open areas and crowds are larger, a portable loudspeaker is sometimes brought in and its mike passed back and forth between the reciters and the actors. The

crowd is by and large attentive during the performance; people who are less interested gravitate to its fringes, where groups of friends stand gossiping, small children play (some with little bows and arrows, acting out their own Ramlilas ), and snack and souvenir vendors operate throughout the program. But any disturbance within the central area is quickly hushed by the spectators, and most of the children—who probably make up 20 percent of the crowd—sit in rapt attention throughout.

The main stage is outfitted with side curtains and floridly painted backdrops depicting columned halls and vistas of formal gardens complete with topiary and fountains—reflecting the Victorian scenic conventions still prevalent in nautanki[*] stagings of romantic and heroic legends.[71] Dashrath's velvet jacket ornamented with gold braid likewise suggests nineteenth-century courtly dress. The costumes of the boy principals, however, resemble those worn at Ramnagar, which are based on religious iconography and the courtly styles of an earlier period.

The role of Dashrath is played by Kashinath Pathak, the schoolteacher who serves as the director of this lila . He gives a highly histrionic portrayal of the king's reaction to Kaikeyi's demands, collapsing on a gilded couch where he remains, writhing in agony, throughout the evening. His overacting strikes me as comic, but my reaction does not seem to be general; some older spectators are moved to tears. There are other notable performances: the man who portrays Sumitra brings considerable poignancy to the scene in which Lakshman's mother accedes to his request to accompany Ram to the forest. His rendition of her famous speech,

My child, Sita is your mother now,

and Ram, your devoted father.

Ayodhya is wherever Ram resides,

as day is where the sun shines.

2.74.2,3

elicits more handkerchiefs. The boys, who are older than those at Ramnagar, also give competent performances. The local Ram, aged sixteen, is in his second and final year of playing the part—for his upper lip already betrays a faint moustache.

The episode concludes at midnight (quite early for a Khojwan performance, as I would discover) with an arti ceremony modeled after that of

[71] On nautanki[*] , see Hansen, "Written Traditions of a Folk Form"; also see her essay "The Birth of Hindi Drama."

Ramnagar: the boy actors are garlanded and worshiped to the accompaniment of a hymn sung by the Ramayanis and showers of blossoms from behind the scenes. At the same time, a magnesium flare is held aloft, to sear the auspicious tableau on the minds of departing spectators.

Nakkatayya

The lila of the nineteenth night is listed on the Khojwan program as "Severing of the nose and ears of Shurpankha, killing of Khar and Dushan etc., stealing of Sita and lamentation." However, it is popularly known simply as Nakkatayya, a colloquial expression for "cutting-off-the-nose," and it attracts the biggest crowd of the whole cycle. Like so much else at Khojwan, it is a borrowing from another production—in this case the lila of Chaitganj, whose even bigger Nakkatayya seems to have given rise to this type of performance.[72] Kumar suggests that the Chaitganj spectacle developed as recently as the first decade of this century; its citywide fame and massive turnouts probably inspired the ambitious merchants of Khojwan to copy it in their lila . They must have gone at it with their usual gusto, for their version is now only a little less famous than its model. Both attract large crowds from beyond the immediate neighborhood, Khojwan drawing more on the southern half of the metropolitan area and Chaitganj more on its northern half.

The Nakkatayya strikingly displays the Ramlila's ability to incorporate other types of folk performance into the prestigious paradigm of the Manas narrative; the resulting performance is both symbolically complex and chronologically extended. For, as Kumar points out, just as the Chitrakut Bharat Milap is renowned for its brevity, so the Nakkatayya is famed for its marathon duration, and the first remark one is liable to hear about it is the admiring comment, "It lasts all night!" It begins in Panchvati, which in Khojwan is represented by the columned pavilion in the central bazaar; here Ram, Sita, and Lakshman are visited by the female demon Shurpankha, Ravan's sister. Spurned in her sexual overtures to Ram and Lakshman, she tries to attack Sita and is mutilated by Lakshman. The subject matter is elemental and highly charged. Conventional (that is to say, male) wisdom regards the demon as emblematic of the oversexed female, whose uncontrollable lust threatens to rob men of their potency. Her mutilation (by cutting off her nose and ears in the

[72] On the origins and contemporary celebration of the Nakkatayya of Chaitganj, see Kumar, The Artisans of Banaras , 180-97.

fashion in which, according to ancient lawbooks, adulteresses were to be punished) is seen as a fitting lesson to the female sex.[73] At Ramnagar, where the mutilation is graphically represented—Shurpankha runs wailing through the crowd with red paint splashed over her costume—I was told by smiling men that village ladies are encouraged to attend this episode "in order to receive a good lesson." At Chaitganj and Khojwan, Shurpankha is portrayed by a female impersonator—a supposed eunuch and, like the demon herself, a socially liminal, comic, and yet repellent figure. Following her pantomimed mutilation, Shurpankha rushes off to the demon fortress of Jansthan—located several kilometers away in the Ravindrapuri neighborhood—to summon the forces of Khar and Dushan, Ravan's lieutenants in the region.

Tulsidas dwells at length on the sallying forth of the demon army with Shurpankha at its head, its foolish leaders arrogantly confident of an easy victory over the mortal princes (3.18.3-12). The ensuing conflict is Ram's first encounter with a demon army and prefigures the great battles of Book Six. In nineteenth-century pageants, this probably occasioned a small procession, such as are still organized around other episodes (Ram's wedding, journey into exile, etc.)[74] In the Chaitganj production this procession grew in size and importance to become an all-night event. The iconographic logic behind the expansion was simple: since demons are known to be form changers, capable of assuming any shape at will, a raksas[*] procession can contain almost anything. Thus, the Nakkatayya has become a sort of visual saturnalia, whose specific features have as much to do with the Ramayan as the floats in a Mardi Gras parade do with the life of Jesus. The procession offers an occasion for ritualized inversion, which allows for the release of pent-up tensions. Shurpankha is defaced in the early evening, and the demon forces are finally annihilated by Ram just before dawn; but in the interval the forces of illusion, sensuality, and artifice take to the streets for a sort of Walpurgis Night of phantasmagoric display. Tulsi himself sang of

Numberless vehicles, numberless forms,

numberless hosts bearing numberless weapons

3.18.5

[73] Note, however, that the justification of Lakshman's act has often been debated, especially in South India; see C. Rajagopalachari's retelling of Valmiki and Kampan, Ramayana , 139n. On the punishment of an adulteress, see Arthasastra 4.10.10; such injunctions are discussed in Pollock, "Raksasas[*] and Others," n. 30.

[74] The growth of Ramlila processions and their acquisition of political and communal overtones is discussed in Freitag, The New Communalism , Chapter 6.

and the Nakkatayya procession, which winds on for hours and contains bands, elephants, dance troupes, and anywhere from fifty to a hundred floats, does seem to approximate this description. All of Khojwan Bazaar is transformed for the occasion: the field before the Ramlila Center becomes a fair, with three country-style ferris wheels, booths housing games of skill and chance, and peddlers of all description; the main street is lined with bamboo railings and festooned with colored lights. It is difficult to say how many spectators witness the procession along its entire route, but thousands pack the central bazaar in the vicinity of the Panchvati pavilion, before which the Ramayanis sit on a lower wooden platform.

The head of the procession arrives in the main bazaar at about 3:00 A.M. , led by Shurpankha, who dances furiously, brandishing a suggestively rounded club that "she" waves threateningly at Ram and Sita. Behind her comes Khar, represented by a figure in a donkey mask (his name in Hindi means "donkey"), and Dushan ("blemish"), a fifteen-foot bamboo-and-paper effigy. The remainder of the procession consists of varieties of folk performance with origins outside the Ramlila .

First there are troupes of Durga dancers, hailing from all over the Banaras area. Each troupe represents an akhara[*] —a combination social, religious, and physical-culture club for men and boys—under the direction of a dancing master.[75] The Durga clubs specialize in a furious style of masked dancing that incorporates elements of martial art. The dancers wear silver masks topped by enormous crowns, and full-skirted costumes. The crowns feature circular coronas extending several feet into the air, ornamented with peacock feathers, mirrors, and other brilliant materials. These male dancers represent—and to some extent, as with all Hindu mimesis, incarnate—bloodthirsty goddesses such as Chamunda and the other six forms of Durga. In martial traditions these terrifying goddesses are associated with other dangerous and powerful female figures such as tantric yoginis and witches, who are believed to congregate on battlefields; like Shurpankha, they are threatening females who eat the flesh and drink the blood of virile warriors.[76]

On the long procession route from Ravindrapuri through Bhelupura

[75] On the contemporary akhara[*] culture of Banaras, see Kumar, The Artisans of Banaras , 111-24; Kumar estimates that there are several hundred such institutions in the city, representing an indigenous ideal of physical culture that has been overlooked by most scholars. On wrestling akharas[*] , see Alter, "Pehlwani. "

[76] In 3.20.14-20, Tulsi depicts these demonic women dashing around the battlefield waving warriors' entrails "like a crowd of children flying kites." A similarly macabre description of blood-crazed yoginis occurs in 6.88.7,8.

to Khojwan, the Durgas of each troupe dance, brandishing swords, daggers, torches, and skull-bowls with which they are supposed to catch the blood of their victims. Within each troupe, there are novice perform-ers—small boys who do little more than march, swaying in costume—as well as accomplished adult dancers who execute more difficult routines. Some carry metal baskets filled with hot coals, which they whirl about their heads on long chains; stirred into brilliant redness and emitting showers of sparks, they blur into fiery halos surrounding the dancer. There are also dance-duels with bamboo staves, and furious sword dances in which the performers slash at the air with gleaming scimitars. At the conclusion of such a piece, the performer appears to go out of control and rushes to the sidelines flailing his weapon as spectators duck for safety; he is quickly seized by attendants who disarm and hold him for a few moments while others fan him, apparently to calm the possessing goddess's rage. Finally each Durga is outfitted with a short sword with which he executes one last whirling dance, ending with a bow and the presentation of his skull-cup at the foot of the platform. A member of the lila committee steps forward gingerly, careful to avoid the still-twitching dagger in the dancer's other hand, and fills the cup with a handful of flowers and tulsi leaves blessed by Ram. This vegetarian prasad is supposed to satiate the goddess, who is then escorted to a side street, where troupe members remove their masks and costumes. Altogether about a dozen Durga troupes, some numbering thirty or forty dancers, appear in the Khojwan procession. The costuming of each varies slightly, especially in the ornamentation of the tall, shimmering crowns. The impassive silver masks are nearly always the same, however, and resemble the Devi images in many local temples. To a trained eye, the iconography of each costume identifies the specific goddess being represented.

After more than an hour of Durga dancing, the next phase of the procession appears: the humorous, eye-catching floats collectively known as svang (satire or burlesque).[77] The use of such floats in Nakkatayya has an interesting history; apparently when the custom originated in the early decades of this century, the floats depicted sexually and socially indecorous situations and participants sang scurrilous songs. In the 1920s and 1930s the "obscene" character of the processions became the focus of a vociferous reformist campaign championed

[77] In other contexts, the term refers to a form of comic theater related to nautanki[*] ; see Hansen, "The Birth of Hindi Drama."

by the Hindi press, especially the socially conservative BharatJivan , and such upper-class educational leaders as Malviya and Sampurnananda, whose criticism of the pageant was ultimately successful in "disinfecting" it. Ironically, although the character of the tableaux changed in response to these criticisms, the identification of the Nakkatayya as a vulgar lower-class event caused the educated elite to permanently dissociate itself from it.[78]

Most floats today have mythological themes—to which no one can object—and thus, suitably reformed, the folk art continues to flourish. The procession I witnessed in 1983 drew svang groups from as far away as Madhya Pradesh. The essence of the contemporary art is grotesquerie and trompe-l'oeil, and most floats consist of frozen balancing acts featuring small children. In one, an (adult) Shiva figure holds aloft two fur-suited child demons, each of whom appears to be speared through the middle, like a cocktail olive, by the prongs of his trident; there are gruesome red stains where the prongs emerge from their bodies. Supported by artfully concealed metal rods, the whole tableau—Shiva, trident, and demons—is balanced on a rotating pedestal high above the street. This pedestal rests in turn on a tractor, but others are supported by bullock carts or even hand-drawn wooden wagons with bicycle wheels. These high tableaux teeter along precariously, the performers sometimes having to duck to pass under power lines. By the end of the procession, many of the smallest "demons" are sound asleep on their high perches, securely held in position by the supporting rods. The floats are wired too, with strings of flashing bulbs or rotating wheels of fluorescent lights. A few have attached generators, but most have to stop periodically and be hooked up to local current in order to give viewers the full effect. The floats are preceded by hired musicians playing drums and shehnai, creating a wonderful cacophony as they proceed through the packed bazaar.

The last phase of the procession is a line of ornate carriages (viman ), resembling the chariots in religious calendar art. Each represents (and hence advertises) a tent house somewhere in the city, which hires out these gaudy vehicles to wedding parties. The last carriage, however, returns viewers to the Ramayan story, for it represents the flying chariot used by Ravan to abduct Sita; it parks alongside the reviewing stand to await the fateful moment.

The sky is growing light by the time the procession ends, and the

[78] Kumar, The Artisans of Banaras , 190-95.

morning star hangs above the packed rooftops fronting the bazaar. No one leaves, because the final phase of the lila is only now to begin, although in deference to the exhausted condition of most participants it will unfold rapidly. The Ramayanis resume their chanting from the Manas ; Ram seizes his bow and quickly dispatches Khar and Dushan. Shurpankha goes wailing to Ravan, who appeals to his uncle Marich to take the form of a golden deer. At Sita's importuning, Ram stalks the frisky animal (a masked dancer in a spangled body stocking) to the delighted shrieks of curbside children; the detonation of a cherry bomb signals its demise. Meanwhile, Ravan approaches in sadhu's guise, portrayed by Khojwan's resident buffoon (who incongruously sports an ocher Ram-nam shawl!); after a lively dialogue, he is suddenly replaced by a conventionally masked figure who has been lurking under the dais and who now seizes Sita and spirits her away down a side street, pausing briefly to battle the noble vulture Jatayu. As the first rays of the sun strike the housetops, the brothers return to the deserted ashram, Ram gives himself up to grief, arti is performed, and the great crowd disperses.

At 7:00 A.M. I am walking to the main road through the back lanes of Khojwan, past an occasional tethered elephant, floats in varying stages of disassembly, and bleary-eyed Durga dancers crowding around an open tea stall. I get into a conversation with a small, wiry man who walks determinedly with a tall staff. He seems oddly familiar, and as we near the main road I suddenly realize where I have seen him before; "Brother, you're Ravan, aren't you?" He confirms with a wry smile and quickly disappears into the haze and the trudging throngs of pilgrims headed, on this auspicious Nav Ratra morning, for worship at the nearby Durga Temple.

Ramnagar: Pilgrims and Singers

Earlier in this chapter I discussed the origins of the Ramlila of Ramnagar, and I devote a later section to its manner of interpreting the Manas text. Since the work of documenting the individual performances of this month-long production has already been undertaken by others, I do not describe specific episodes in detail here.[79] Instead I focus on two aspects of the pageant that have received little attention: the relationship of the performances to a traditional Banarsi pattern of recreation, and the role of the Ramayanis, or Manas chanters.

[79] See the work of Schechner and Hess, referred to in note 4 above.

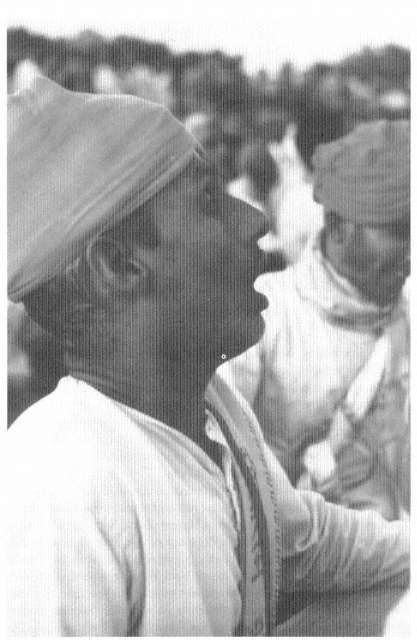

Figure 25.

A procession during the Ramnagar Ramlila (photo courtesy of

Linda Hess)

The Art of Crossing Over It is surely clear to anyone who has ever spent time in the city that the Banarsi way of life consists of more than ritual bathing and visits to temples; even these and other pious activities for which the place is justly famed have (in Western terms) "secular" dimensions that contribute to their appeal. Yet scholarly writings on the city have tended to focus on its theological status and the complex hierarchy of its religious institutions and functionaries, and only recently has a study examined the everyday life of its people, particularly their concept of "Banarsiness" as "an ideology of the good life."[80] Central to this ideology, as Nita Kumar discovered, is a cycle of leisure activities based on indigenous concepts of the person, space, and time, articulated in terms whose importance has often been overlooked "because they perhaps do not fit very neatly into a text-based or ritual-oriented scheme. Among these are the principle of pleasure (khusi , anand ), the philosophy of freedom and carelessness (mauj, masti ), the image of play (khel, krira[*] , lila , manorañjan ) and a stress on individual taste, choice, and passion (sauk )."[81] That Kumar's subjects represent some of the city's poorest artisans (such as metalworkers and woodcarvers) may appear paradoxical; the economic realities of these men's lives—starkly documented at the beginning of her study—do not suggest a great scope for leisure. Yet Kumar vividly catalogs the surprising range of participatory recreations in which artisans engage: poetry and singing clubs (including Ramayan singing groups), Ramlila troupes, wrestling and swimming clubs, and the full array of fairs, temple srngar[*] festivals, processions, and other annual celebrations in the city concerning which a popular saying holds, "Eight days—nine festivals."[82]

Among the most popular recreational activities is the practice known as bahrialang[*] (literally, the "outer side" or "farther shore"), which refers to boating excursions to the opposite bank of the Ganga and to the activities pursued there. In questioning some of the city's poorest artisans concerning their recreational activities, Kumar found that most would at first vehemently deny having any—"Are sahab , what entertainment can we poor people have?" Her inquiry might have ended there, had she not discovered the magic formula bahrialang[*] , at the mention of which the same men would wax eloquent concerning its exquisite pleasures—whether enjoyed daily, weekly, or more infrequently.[83] The essential constituents of the practice are so simple—one

[80] Kumar, "Popular Culture in Urban India," 324.

[81] Kumar, The Artisans of Banaras , 236.

[82] "Ath bar[*] , nau tyauhar"; quoted in Jhingaran, "Ham sevak," 20.

[83] Kumar, The Artisans of Banaras , 83-110, 230.

crosses the Ganga, relieves one's bowels, and washes one's clothes—that an outsider may not readily grasp just what is so recreational about it. But of course, it is never a solitary activity; it is enjoyed with friends, and much time is whiled away in talking, joke telling, and singing. In addition, it provides a complete and much-needed change of environment. I have already mentioned the distinction between the two banks of the river: the city side and the "outer" side. The former is civilized and sacred, but also chokingly congested. The farther shore, in contrast, is a sandy, uninhabited floodplain, an accessible wilderness. As such it offers a refreshing antidote to the crowded bazaars and cramped working and living spaces that otherwise form the boundaries of the city man's life.

There are other dimensions to the excursion as well. Since the outer side is a ritually impure area, it has always been regarded as a good place to relieve oneself, and there is an old tradition that exemplary people repair beyond the sacred borders of the city for this purpose. The appeal of this aspect of the trip must be understood in the context of a culture in which personal hygiene practices are powerfully associated with ideals of purity and deep levels of identity. The journey itself is also pleasing; the river is the city's great scenic attraction as well as its claim to spiritual greatness, and there is no better way to appreciate its beauty than from a boat. The act of crossing the Ganga inevitably has a religious dimension—Banaras, like all pilgrimage centers, is a "crossing-place" (tirthsthan ), where believers are assured safe passage over the turbulent flood of this world—and every Hindu reaches overboard in midstream to sprinkle a few drops of water on his head while uttering a formula such as "He Mata Ganga, teri sada jay!" (O Mother Ganga, may you ever be victorious!). Finally, an essential ingredient in the pastime for many Banarsis is the consumption of bhang and the resultant intoxication. In most excursion parties one man assumes the job of preparing the treat: crushing the leaves and straining a decoction that is then drunk, or shaping the pulp into little balls—combined, if budget will allow, with raisins, nuts, and savory spices—that are eaten. A moderately powerful psychoactive drug that alters visual and time perception, bhang has a religious dimension as well, since it is associated with yogis and their lord, Shiva, who is said to consume great quantities of it. Needless to say, a draft can add a new dimension to mundane activities: one can, for example (as Kumar was gleefully told) seize a bar of soap and spend a satisfying three-quarters-of-an-hour deeply engrossed in laundering one's dhoti.[84]

[84] Ibid., 84.

In his writings on Ramlila , Schechner observes that an important characteristic of Banaras's most famous production is the fact that it is not located in Banaras.[85] By constructing their dramatic environment on the further shore, the royal patrons created a theater that urban residents have to cross the Ganga daily in order to reach. Schechner vividly describes the difficulties and even hazards that this pilgrimage can entail, especially during the early part of lila season when the river is still swollen from monsoon rains. At the very least, the trip is time-consuming; a person coming from the city may require two or more hours simply to reach the lila site. If he is someone whose personal regimen is to witness every performance from beginning to end, attendance will be more than a full-time job, easily occupying ten hours a day. But I am convinced that time is still a relatively cheap commodity in Banaras and that some of the inconvenience that I, for example, experienced in getting to Ramnagar each day was not felt to the same degree by local pilgrims, who seemed to accept the journey itself as part of the recreational experience of lila . For among other things, the Ramnagar Ramlila is a grand, month-long bahrialang[*] excursion with all that this implies.

Many thousands of people attend the Ramnagar pageant sporadically, turning out for big events such as the breaking of Shiva's bow and the slaying of Kumbhakarna. But there is a core group of spectators—probably amounting to one or two thousand—who attend daily. To be able to do so is highly valued. The question I was invariably asked by fellow audience members was "Do you come daily? " and their satisfaction when I answered in the affirmative was evident, for regular attendance is the ideal, although everyone is not able to manage it. The great exemplar of such dedication is the maharaja, the patron and principal spectator.

Those attending daily fall into two categories: sadhus and nonsadhus. As already noted, sadhus in large numbers—mainly Ramanandis—reside in Ramnagar during the month of lila ; special camps are set up for them and daily rations are provided from the maharaja's stores. With their sectarian marks and seamless garments (or lack of them, if they belong to naga , or "naked," orders), the sadhus are a distinctive presence at the festival grounds, where they often cluster around the boy actors to entertain them with devotional singing and ecstatic dancing. But the householder who comes daily from the city is no less readily identifiable, for he too affects a distinctive costume. He is known as a nemi (from niyami , "one who adheres to a regimen") or by its expanded

[85] Schechner, Performative Circumstances , 242-45.

variation, nemi-premi (the latter connoting "lover" or "aficionado"). He typically wears a clean white dhoti and baniyan (T-shirt), a cotton scarf (dupatta[*] ) block-printed in a floral design and tied as a diagonal sash across the chest, and yellow sandalwood paste on the forehead. He goes barefoot—this is part of his regimen—and carries a small wooden stool for comfort as well as protection from dust and mud in the varied environments. He may also carry a bamboo stave with a polished brass or silver head.

According to nemis , their costume has no special significance. Its details are either utilitarian (the staff is a convenience for walking and a protection against dogs when returning home late at night) or else (as in the case of the dhoti and the scarf) simply reflect "the old-time style of Banaras city." Since the Ramnagar production is a self-consciously old-fashioned event, it is appropriate that its core audience dresses accordingly; I have seen spectators change out of Western-style pants and shirt at the riverside, donning nemi dress and placing their carefully folded "work clothes" in a bag. Other aspects of the regimen include a bath in the Ganga before each performance and, of course, daily attendance. This may not mean witnessing all performances in their entirety; many regulars pick and choose among the episodes, giving their full attention only to favorite ones. But all make a point of being present during the concluding arti ceremony each night, when the divine presence is considered strongest. Some staunch nemis observe a daily fast, which they break only after they have had the Lord's darsan at arti time.

Although I initially understood the Ramnagar regimen as a kind of religious austerity, I gradually became aware, in conversations with aficionados, of the sensual and aesthetic richness of the nemi experience. One lila regular of the milkman caste came from a village on the western outskirts of the city. Although he had completed secondary school and was employed in a railway office, this man retained a strong taste for traditional Banarsi pastimes and was a great devotee of bahrialang[*] . Together with a group of friends, he owned a share in a boat kept at Gay Ghat and used for daily excursions throughout much of the year. During the month of lila , however, the boat brought the group to Ramnagar. This man's description of his daily routine during the season was delivered with evident relish and testifies to the pleasures of the pilgrimage for many regular participants:

During lila I go to work very early and leave the office at about 11:00 A.M. I go home and take a light meal, then head for the ghat to meet the others. First we row across to the other side and stop there for a while. We take some

dried fruit and a little bhang—not too much, or we'll get sleepy—then a glass; of water to cool the body. Then we go off and attend to nature's call, then meet and row to Khirki Ghat [at Ramnagar—a strenuous journey against the current; the men row in teams, chanting to set a steady rhythm]. Then have a swim and wash clothes. Then rub down with oil, then dress. Prepare sandal paste and apply it, to cool the forehead. Also a little scent at each ear, according to the weather. Then go for God's darsan .[86]