Chapter IV—

Haut-Bourgeois and Aristocratic Building, 1540–1600

1—

Class, Classicism, Nationalism and Anti-Classicism

Renaissance Architecture encompasses as many distinctive national and local styles, Vitruvian, non-Vitruvian and anti-Vitruvian developments as there are European languages and dialects. The 'classical language of architecture' in the sixteenth century never developed a common usage agreed and understood by amateurs, scholars and practising architects. The example of the relationship between the archaeological surveying and research by Palladio and his own architecture is one of many enigmas; it is significant that he published his villas in 1570 with short, bald descriptive notices and made no attempt to describe his personal intellectual and creative methods. International architectural movements based on the inspiration of Greece, Rome or personalities did not develop in the sixteenth century, which might be described as an age of national and regional classicisms, and the architectural literature of the time illustrates more discordances and diversities than influences between Italian and northern European styles and practices. Philibert de l'Orme's Architecture was written for a French not a European public. Serlio's undogmatic pattern books were the only international publishing success in the field of architecture to reach patrons, architects and master masons[1] and to offer designs and models of windows or arcades which need not impinge on regional building customs, but Paris and the Ile de France had their own Serlio in Androuet du Cerceau whose Livres d'Architecture of 1559 and 1582 showed town and country houses in various French idioms and shorn of clear references to Italian villas and palaces.[2] Serlio was deeply conscious of the contrast between building and architectural style in Italy and France and in a circumspect manner sought to draw closer the 'modo di Francia' to the Bramantesque tradition in domestic architecture seen in the manuscripts of his sixth book which was never published.

A description of the architecture of Renaissance Paris is not the story of a coherent stylistic development. Social conditions can be used to outline the evolution of plan-types, but social attitudes and traditions can be made to help in elucidating the diversity of styles across the second half of the century or even within some of its decades. Architectural writers gave plenty of stern advice on the choice of sites, the need for prudence in selecting an architect who could be counted as both cultured and

technically competent, and prudent over the dangers of overspending, but several sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century French writers on economic, legal and political matters made pertinent critical comments on the taste for antique and modern foreign art in general and building as a vanity in particular. It cannot be surprising to see more than one community of ideas dealing with an art as public, exclusive and expansive as architecture, and which could excite admiration, envy or contempt.

The influential publisher and classical scholar Henri Estienne, when writing an extensive commentary on Herodotus in the early 1560s, was concerned about indiscriminate adulation for the antique and Italian in painting and sculpture,[3] and the economist and political philosopher Jean Bodin, in a tract on the causes of monetary inflation of 1568, drew his readers' attention to the problem of importing instead of manufacturing luxury goods long before Henri IV or Colbert made it an issue in national policy; he complained of aristocrats' pride and profligacy as builders and collectors and surprises us by singling out Pierre Lescot as a great native painter.[4] Amongst the many texts which might be quoted from the time of the traumas of the religious wars, the most interesting is that by the Parisian Bernard de Girard, seigneur du Haillan (c. 1535–1610), a royal secretary to Henri, duc d'Anjou the future Henri III, historiographer to Charles IX, who ended his days as genealogist to the Order of the Saint Esprit for Henri IV.[5] In a brochure written in 1574 and published in 1586 called the Causes de l'extreme cherté qui est en France he wrote

'Let us now turn to the buildings of present times, then to their furnishings. It was but thirty or forty years ago that this excessive and magnificent manner of building came to France. Formerly our fathers were content to build a good house, a pavilion or a round tower, a menagerie and other accommodation needed to house themselves and their family, without erecting the superb structures as today with large main blocks, pavilions, courts, back courtyards, service courtyards, galleries, halls, porticoes, flights of steps, balusters and other such things. Not the slightest care is taken with the geometrical proportion in the architecture of the outside, which in many buildings has upset the commodiousness of the interior; once one knew nothing of confecting so many friezes; cornices, frontispieces, podia, pedestals, capitals, architraves, stylobates, flutings, mouldings and columns and, in brief, one was not aware of all of these antique manners of architecture which mean spending a great deal of money and which, more often than not, make the interior ugly in order to embellish the exterior; one knew nothing of putting marble or porphyry on fireplaces nor around the doors of houses, nor of gilding the beams and joists.

Girard was the most virulent critic to single out the classical style for special criticism. Others were less assertive but had their doubts over the

wisdom of adopting an imported fashion which had proved costly to many whom they deemed vain or over enthusiastic. The Italian 'bloodsuckers' at the court of Catherine de Medici were blamed by Huguenot writers for many of the nation's ills,[6] and conspicuous or ostentatious extravagance rather than the continual warfare was the cause they favoured for the ruin of eight out of ten French noble families. François de La Noue (1531–91) and his Discours politiques et militaires , written in 1580 and published in 1587, is the best known of these and was the most influential book abroad on the plight of France. It contains these observations on the pitfalls of building and architecture, after some similar comments on clothes and before others on furniture and food.

Let us now come to the second article of our vain expenses, consisting of the immoderate affectations that sundry have for stately buildings. For although it has been so from the beginning, yet it was little compared to our own times, when we see the qualities and the number of buildings surpassing olden times. And especially our Nobility have exceeded in this, rather for vain glory than any necessity. I suppose it is not much more than sixty years ago that architecture was restored in France, where before men had lodged grossly. But since then the fair traits of this art have been revealed, many have endeavoured to put them into practice. If none but some of the great and the rich had employed the abundance of their crowns upon such works, that would not have been reprehensible, considering they were ornaments both for the towns and for the countryside. But following their example the lesser rich, even the poor, have wanted to set their hands to such work, and without thinking were obliged to take on much more than they foresaw: and that not without repentance. The lawyers and above all the treasurers have likewise increased the ardour of the lords for building. For they say: "How is this? These men that are not so well established as us build like Princes, and shall we sit still?" and so envious one of the other, a multitude of fine houses have been built, and often by the ruin of revenue, which has gone into other hands, because of this vehement passion which they have for putting one stone on top of another. How many are they that have started sumptuous edifices, which have been left unfinished?, having come to their senses half way through their folly. In every Province we see but too many examples. It may be that some when they see themselves so well clothed and spangled in gold, have said "This cage is too small for so beautiful a bird, it must have a more stately one". To this reasoning some flatterer may have replied "Sir, it is a shame that your neighbour, who is no better than yourself, should be better housed. But take heart, for he that begins boldly has already done half of the work, and the means will not elude the wise man." He, feeling himself scratched where it itched, forthwith conceived in his imagination a design, which he began with pleasure, continued with

pain, and completed in sorrow. Often it comes about that he who has built himself a house fit for a lord with an income of twenty-five thousand livres, which his heir, finding himself with one of only seven or eight hundred, and being ashamed to lodge his poverty in such stateliness, has sold it to buy another, suited to his income. And he that would not sell has been driven "to feed upon small loaves" (as one says) and he feasts his friends, when they visit, with discourses on architecture. When Father Jean des Antomeures (who was one of the most worthy men of our times) entered these magnificent houses and châteaux, where he saw lean kitchens, he used to say "Oh, to what purpose are all these fine towers, galleries, chambers, halls and closets, with the cauldrons so cold, and the cellars so empty? By the Pope's worthy pantofle (for that was his customary oath) I would rather dwell under a small roof, and hear from my room the harmony of the spits, smell the savour of the roast, and see my cupboard glorying in flagons, pots and goblets, than to dwell in these great palaces, to take long walks, and to pick my teeth fasting in the Neapolitan fashion." I accept the opinion of those who advise that if they build, it is on the condition that they sell little or none of their goods, and he who does otherwise, I refer him to the censure of Father Jean des Antomeures. I am well aware that one of the most remarkable things which one notices in France are the fine buildings strewn across the country, which are not to be seen elsewhere. But if one also counts how many of such splendours have reduced men to beggary, one will say the the product indeed is costly.[7]

Care has to be taken when evaluating such texts, to understand the political background and the motives of each of the authors. In general, writers on both sides of the religious divide wrote in a similar vein, lamenting the profligacy of the old nobility and despairing of the temptation to compete with the contemptible class of rich lawyers, merchants, tax gatherers and Italian bankers. Girard and de La Noue were saddened by the decline both of the wealth and of the influence and prestige of the French nobility and aristocracy, and nostalgically saw the reigns of Louis XII and of François I as a last flowering of the natural, traditional and just order of France. The issues which led to the eruption of the Fronde can be traced back to the reigns of Charles IX and of Henri III. In a society where regulations were drawn up, but rarely obeyed, reserving the wearing of certain luxury cloths for the most noble, appearances were made to matter in the maintenance of the decorum of rank of an unstable hierarchy. The anatomy of class and privilege described by Claude Loyseau in his Cinq Livres du droit des offices, suivis du livre des seigneuries et de celui des Ordres of 1610 helps in an understanding of many of the internecine rivalries of the late sixteenth century in an age of numerous unholy alliances. In his Traité de l'économie politique published in 1615, Montchrestien fumed, 'At present it is impossible to distinguish by appearances. The shop keeper is dressed like a

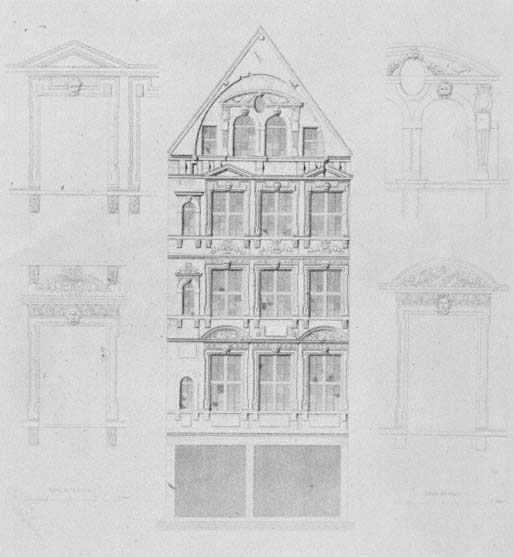

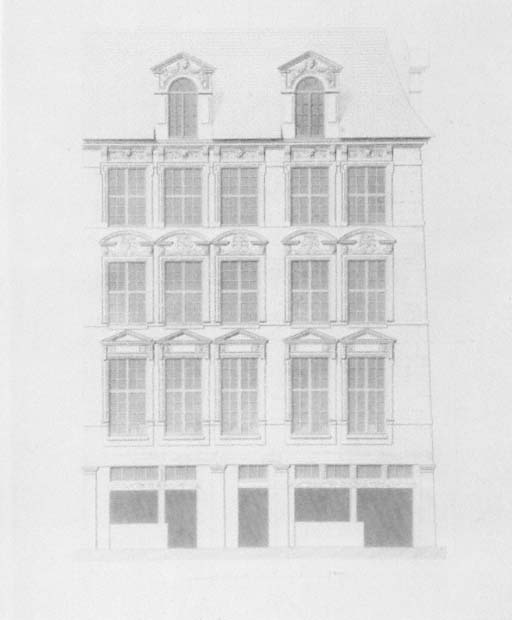

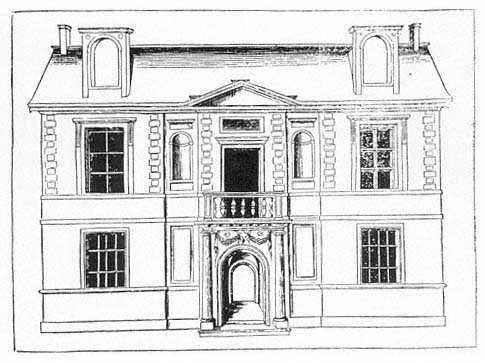

71–72

Houses on the rue Saint-Denis and on the rue Neuve Notre-Dame,

as published in Lenoir's Statistique Monumentale du Vieux Paris , 1867. These are the only detailed

records of examples of substantial sixteenth-century bourgeois houses with elaborate

classical decoration. Bernard de Girard's complaint that ' . . . the interior (is made)

ugly, in order to embellish the exterior . . .' cannot be made to apply to these compositions.

The interior arrangements were not adjusted to make the façades symmetrical. The influence

of Lescot's window mouldings on the Louvre is seen on the house on the rue Saint-Denis,

which encourages a dating of 1555–1565. The house on the rue Neuve Notre-Dame

is very difficult to date, but may have been built during the first half of the 1560s at the earliest.

The principal ornamentation of both houses is the use of richly carved friezes and

varied pediments, with no attempt made to articulate the façades with orders. Both houses

might have been older structures embellished by proud, but as yet, unidentified owners.

gentleman . . . Moreover, who cannot see how this conformity of ornament does not introduce a corruption into our ancient discipline?' Social decorum must be considered in a discussion of the architectures of the second half of the sixteenth century in Paris where the scale and style of a building could be influenced by concerns remote from the 'classical language of architecture'. Girard's and de La Noue's words should not be seen as satires on building practice, for the example of Paris in their times yields many examples of the unfinished houses and the frequent changes of ownership mentioned by them. In the 1580s, when their essays were published, houses for royal, aristocratic and haut-bourgeois patrons were being built in distinctive and contrasting styles, which visibly reflects attitudes common to political writers and an architect of the status and calibre of Philibert de l'Orme, who built his own house in a manner he deemed appropriate to his resources and class (Figs 92–94).

2—

Haut-Bourgeois and Aristocratic Town Houses, 1540–1600

A comprehensive and satisfactory architectural history of Renaissance Paris may never be written for there is no consistency in the documentary and graphic records of the best of bourgeois and aristocratic building in the capital. For every block and district of the Marais, les Halles, the quartier Saint-Honoré or the Left Bank there is either a documentary shortage, or a lack of drawings or engravings, or both. Little more than a dozen private houses built between 1540 and 1600 can be adequately described from both plans and elevations, and singling out those of which adequate records happen to have survived for a stylistic study has many pitfalls, if only because such a study can have none of the neatness of a limited chronological and topographical account. The architectural wealth of lost Paris can be imagined by reading down the long lists of the palaces and houses of French and foreign princes, archbishops, ambassadors, Royal favourites and bankers given by Henri Sauval, the first methodical historian of the city writing in the 1650s.[8]

Pierre de Bourdeille, seigneur de Brantôme, the best-known chronicler of the lives, loves and deeds of the prominent figures at the French court in the sixteenth century, enthusiastically wrote of Fontainebleau having thirty houses or rather 'palaces, vying with each other to please their King, of Princes, Cardinals and great Lords'. In his notice on the château published in 1579, Androuet du Cerceau wrote of François I's feeling that at Fontainebleau he was chez soy , of how the best of his collections were bought for Fontainebleau and mentioned the many lords who built there because of the King's preference for the place. Du Cerceau added, 'But since the death of the late King François [in 1547] the place has not been so habituated nor frequented, which will be the reason for its decay with the passage of time, as at very many other places which I have seen, because

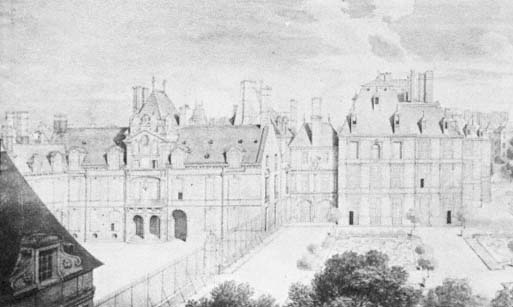

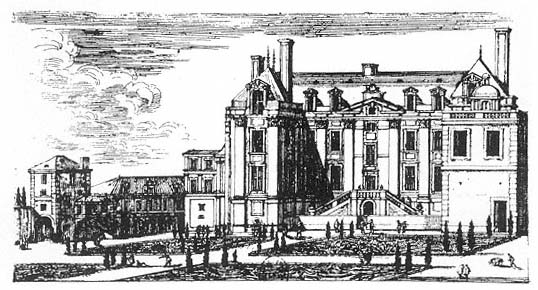

they are no longer lived in.' This prophecy was fulfilled, for all of the great houses have disappeared, and the town and the precincts of the château now reveal almost nothing of its architectural eminence in the first sixty years of the sixteenth century. The most vivid record of these 'palaces' is a group of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century surveys which show the impressive size and plans of some of these 'palaces' (Fig. 73). They are of central importance in expanding the fragmentary story of aristocratic town-house planning during the reign of François I, when the social and diplomatic life of the court had not yet settled in Paris, which had happened by the time du Cerceau made his comments during the reign of Henri III 'the most Parisian of all French Kings'. In the earlier reign the need to be near the King and to be able to entertain him lavishly when he was a l'aise was the motive for most of the dignitaries who invested in building at Fontainebleau rather than Paris. The Chancellor Antoine Du Prat took over the Hôtel de Sens in the capital after the death of Tristan de Salazar, but with a substantial hôtel which he retained at Fontainebleau for himself, his secretariat and household, his role as François I's most trusted political and financial adviser was made more efficient and closer, a forerunner of the ministries built at the next surrogate capital of France — Versailles.[9] Little is known of the stylistic details of the houses built for princes, cardinals and royal mistresses on spacious sites close to the château,[10] except the opulent 'Grand Ferrare' or the urban château built between 1542 and 1546 for the Papal Nuncio, Cardinal Ippolito d'Este recorded by the luckless Serlio in the manuscripts of his sixth book.[11] (Fig. 75)

The form and arrangement of the Hôtel de Ferrare are of fundamental importance for the study of subsequent developments in the capital, where its layout might have been imitated more often had the lotissement plots been more spacious. The courtyard was almost square, with a corps de logis about 38 metres in length and lateral wings just under 30 metres long, the right-hand wing containing the offices. Only the corps de logis had cellars; the ground floor was raised five French feet above the level of the courtyard, and the single storey was 16 French feet in height to the ceiling. Built in sandstone with no classical refinements such as columns or pilasters the main block had restrained colour accents with red brick being used for the entablature mouldings and the dormer windows. The earliest known contract for the house from March 1542 states that the dormers were to be copied from those of the Hôtel of Ambroise Le Veneur, Cardinal of Lisieux which recently had been completed at Fontainebleau, an interesting early example of a component in a design being quoted from a building where the results were admired or considered satisfactory, and which saved the parties to the contract from the trouble of drawing up specifications. The same contract only describes the main block and the offices; the gallery wing with the centrally-planned chapel at its end, the first in French architecture, must have been a part of Serlio's contribution

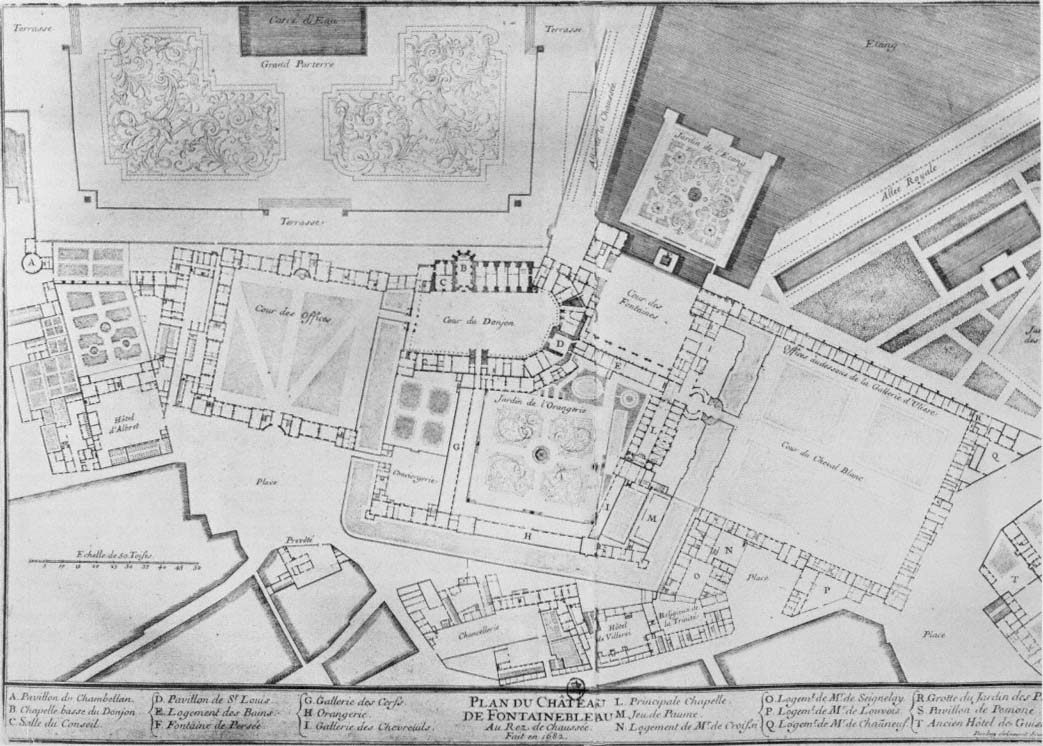

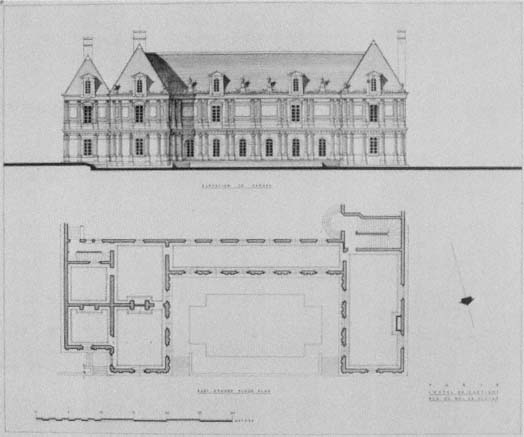

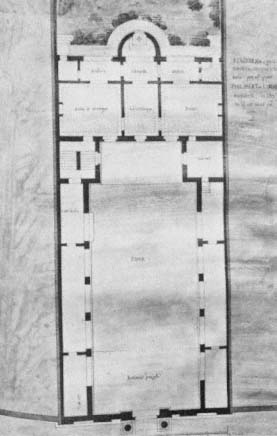

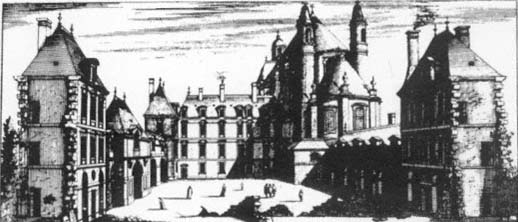

73

Fontainebleau. Plan of the château and of houses in the immediate vicinity.

Engraving by François d'Orbay of 1682.

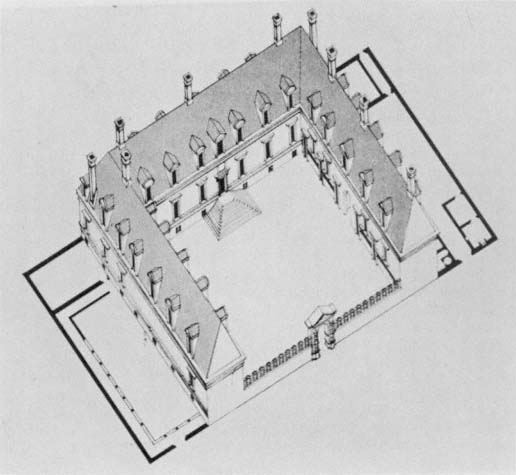

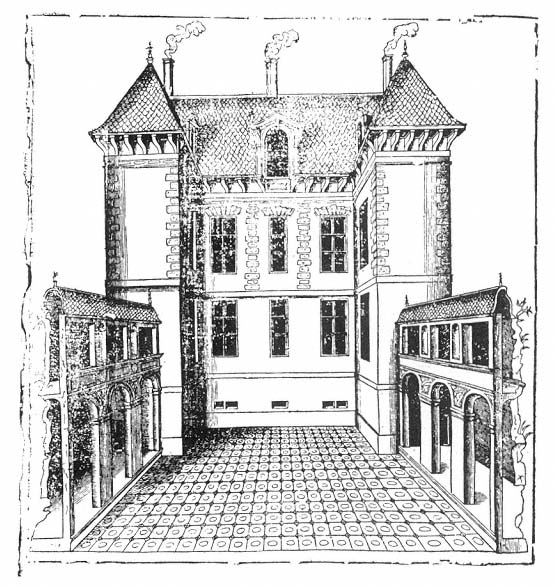

74

Hôtel de Ferrare, Fontainebleau. Bird's-eye view reconstruction from Rosci and Brizio.

to the design of the house for which he was paid by the Cardinal in April 1544. Another interesting feature in the planning of the 'Grand Ferrare' is the passage way through the middle of the office wing for carriages and carts into the stable courtyard behind, thus segregating all the services in the right-hand quarter of the site, with the kitchens the farthest removed from the Cardinal's apartments at the far end of the offices (Fig. 75). The corps de logis was an enfilade one room deep to give the best possible light, and with a garden front of just under 55 metres in length, it bisected the site leaving the garden completely private and free of the encumbrances seen in the plan of the Hôtel Le Gendre. The plan of the 'Grand Ferrare' is a distillation of many traditional elements and recent elements in French building, but was in many ways an ideal arrangement which could not be

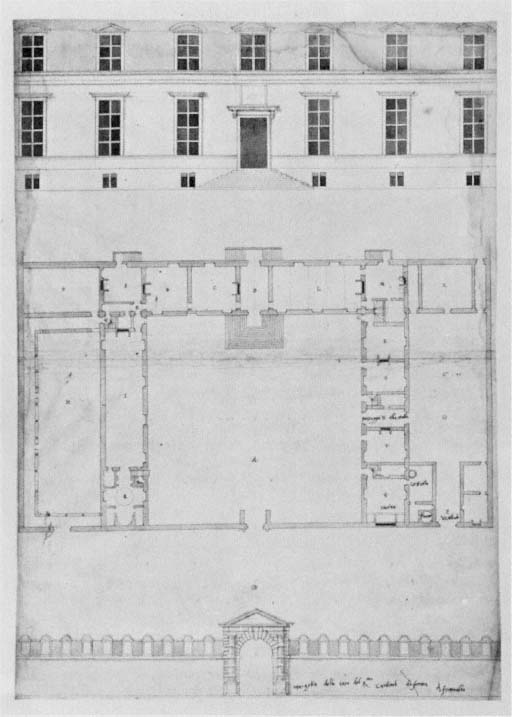

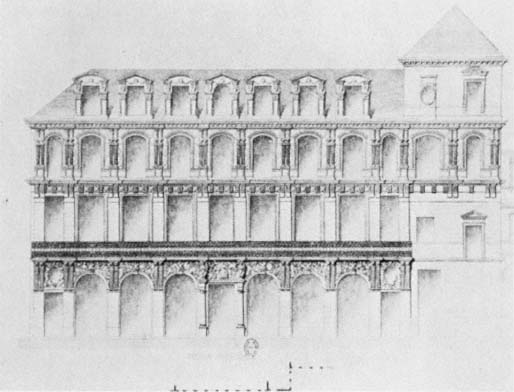

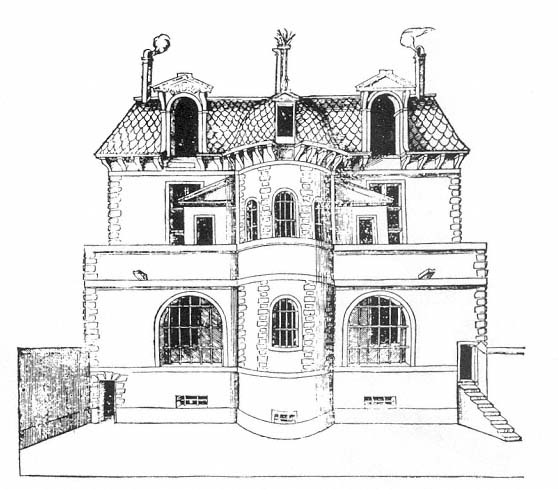

75

Hôtel de Ferrare, Fontainebleau.

Courtyard elevation of corps de logis and plan by Sebastiano Serlio. (Avery ms. n° XI)

imitated widely; the house at Fontainebleau had a regular spacious site which meant that it could serve as a model for building in Paris only for the handful who had bought, or who accumulated after the first sales, more than one of the larger rectangular plots of the lotissements , so that there was enough space to separate services from the owner's living quarters.

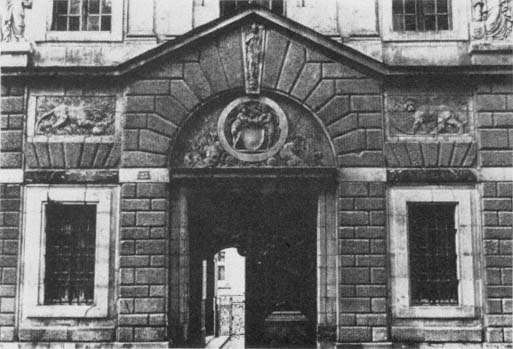

Serlio made it his business to assimilate building practice in France and, despite its innovations, the French rather than 'imported' characteristics are more distinct in the plan and elevations of the Hôtel de Ferrare. The crenellated entrance screen has been seen before at the Hôtel de Cluny where there was little space and probably no wish to close the courtyard with a wing on its south side, but courtyard screens were common at farms, manors and country houses before and after the 1540s. The only surviving feature of the Hôtel de Ferrare is Serlio's boldly rusticated entrance arch exemplifying not only the temporal power and status of the owner, but also suggesting a country or rustic association (Fig. 76). The view of the 'Grand Ferrare' as a country house brought into the town is strengthened in its similarities with Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, the first of Philibert de l'Orme's major château commissions after his return from Italy, begun before 1541 for another Cardinal, Jean du Bellay, Bishop of Paris (Fig. 79). De l'Orme's first project for Saint-Maur was a rectangular courtyarded house and like the house at Fontainebleau it was to have a single main floor raised above ground level, on top of cellars. Charles IX in the 1560s referred to Saint-Maur as his cassine ,[12] and antique and modern Italian ideas on the design and organization of a retreat or villa of a great man clearly were in de l'Orme's mind with the first project for Saint-Maur with its tall basement and clearly defined piano nobile distinguished by Corinthian columns and pilasters.[13] Ippolito d'Este would not allow Serlio to publish the Hôtel de Ferrare as it was built, because he felt its appearance might provoke scorn.[14] The Italian could well have been impressed by his brother Cardinal's house, with its like form and sophisticated demonstration of a correctly proportioned order on a fully extended and developed basement and superstructure, beside which the corps de logis of the Hôtel de Ferrare looked austere. The real splendours of the 'Grand Ferrare' were inside, as can be imagined from the description by Giulio Alvarotto, the Ferrarese ambassador, of the reception, given by Ippolito d'Este in honour of the King at the house in May 1546.[15] The project which must have given more satisfaction to Ippolito d'Este than his hôtel at Fontainebleau is the house and gardens of the Villa d'Este at Tivoli, famous within his own lifetime for the opulent decorations of its interiors and the sculpture, fountains and waterworks in the park as can be seen in Montaigne's account of his visit.[16] The Hôtel de Ferrare was completed shortly after the lotissement of the Culture Sainte-Catherine at a time when several of the class of lawyers and treasurers, singled out by De La Noue as the newly rich with building ambitions, were arranging for the design and construction of their new town houses in the capital, and prominent amongst them

76

Hôtel de Ferrare, Fontainebleau. Entrance gateway.

77

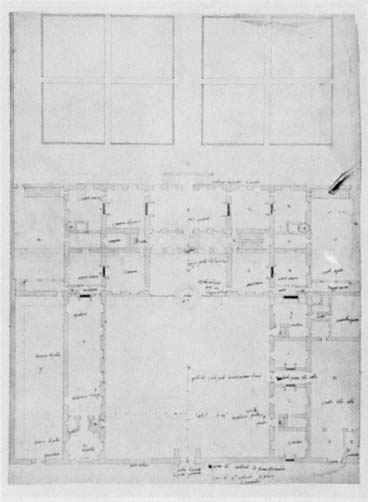

Hôtel de Ferrare, Fontainebleau.

Plan of an enlarged project by Sebastiano Serlio. (Avery ms. n° XII)

was Jacques des Ligneris, President of the Parlement de Paris.

With five well-sited plots of the Culture Sainte-Catherine (numbers 27 to 31 in Fig. 18) des Ligneris and his unidentified architect had several options in planning and orientating the house, and they chose to make the entrance on the east side on a plan clearly adapted from the Hôtel de Ferrare (Figs 80–84). The Hôtel des Ligneris, later, and now the Hôtel de Carnavalet, is a reduced variant of the house at Fontainebleau with a courtyard of about 18 metres in width by 21 metres in length and a garden front of just under 30 metres. Like that 'Grand Ferrare' the main block faces an entrance screen, with a gallery wing on the left of the courtyard and a stable courtyard in the right-hand side of the site with a separate gateway to the street, and with the kitchens relegated to the basement in the south eastern corner. Crossing the court the main block was entered in the right hand

78

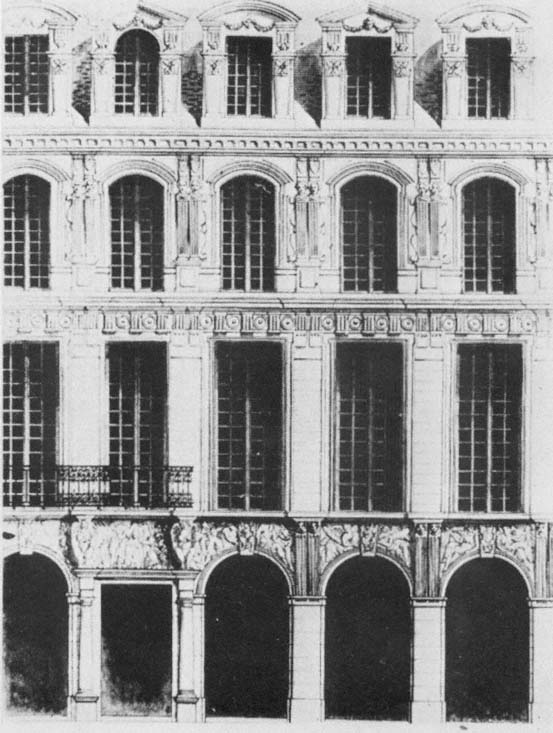

Hôtel de Ferrare, Fontainebleau.

Elevation of a garden façade for the variant Fig. 77. Drawing of c. 1550.

Private collection, London.

corner where there was the main staircase pavilion, an arrangement which avoided taking space from the suites of rooms of the ground and first floors. The main block of two equal floors, five bays wide, with a single-bay pavilion on the left for the spiral stair joining the gallery, and a two-bay pavilion on the right for the escalier d'honneur, must be the original form of des Ligneris' house, but the appearance of the main block above the first-floor cornice and of the gallery wing above the arcade are later alterations. The right-hand wing, which replaced the stable courtyard is the work of François Mansart of 1660–1661, and was further altered in a drastic restoration of 1866–1870. The balustrade above the first-floor cornice of the main block and the three pedimented dormers were added during the nineteenth-century restoration, and are copied from Jean Marot's engraved proposals of the 1650s for the remodelling of the house, which the nineteenth-century architects mistakenly believed to be a record of the original appearance of the Hôtel des Ligneris/Carnavalet before Mansart's additions. The late nineteenth century also saw the destruction of the series of decorative medallions, on the ground floor of the corps de logis, one of which is seen in Hénard's drawing (Fig. 81a). The enfilade of reception room, two further rooms and cabinet at the far end becomes a very familiar feature in the seventeenth century when the etiquette of how and where a lady or gentleman received their guests was fully evolved.[17] The main block of the Hôtel des Ligneris might be read from right to left as public to private rooms following the system which had evolved in the royal apartments in the Louvre.[18] The purpose or function of the gallery remains to be explained; the evolution of the gallery in the Middle Ages

79

Saint-Maur. Courtyard elevation of the corps de logis .

Drawing for Le Second Volume des plus excellents Bastiments de France

by Androuet du Cerceau of 1579.

and the Renaissance is a favourite matter of argument amongst architectural historians.[19]

The des Ligneris family retained seven servants for their needs and comforts, a number which may seem small when compared with aristocratic households of the period. An early eighteenth-century writer estimated that a third of the population of the city was employed in domestic service, and this might have been the situation in the mid-sixteenth century.[20] Des Ligneris was probably amongst those who arranged a marché de pourvoierie or a contract with an outside, professional buyer for the supply of fresh foods from the various Paris markets.[21]

The architecture of the entrance front and courtyard elevations were much altered in the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. The rusticated entrance arch is datable to about 1550 and conventionally is attributed to Pierre Lescot, (Fig. 83) and there can be little doubt that a composition of rustication without an order must be the work of a court architect.[22] The publication of the 'rustic' and the 'delicate' doorways and arches in Serlio's Livre Extraordinaire at Lyons in 1550 made widely known the freedom and whimsy possible with the use of rustication. For the Hôtel des Ligneris the architect devised one of the most 'delicate' of 'rustic' designs in comparison with the massiveness and rougher finish of Serlio's models. The fine proportions and the eccentric cornice with its obtuse angle in the centre to suggest a pediment influenced the design of many gateways and arches built in Paris in the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[23] The very

80

Hôtel des Ligneris (Carnavalet).

Reconstruction drawing of its state in 1558, from the inventory of the possessions

of Jacques des Ligneris. Jean-Pierre Babelon, inv., Jean Blécon, del.

satisfactory reconstruction of the entrance front, devised by Jean-Pierre Babelon and drawn by Jean Blécon (Fig. 80), shows an architecture of distinctive parts, with the immodest triumphal arch flanked by two pavilions made up of three storeys. Above the ground-floor storey is a mezzanine, which with the stables in the right-hand pavilion could not have expressed a floor level, and with another storey on top whose walls were the same height as the ground floor but aggrandized by pitched roofs and pairs of tall dormers with arched windows capped by shallow curved pediments. The top floor of the left-hand or south-eastern pavilion might have had a room used by des Ligneris' family or their servants, but the use of its twin over the north-eastern pavilion is puzzling since it has no covered access from the main block or from the other pavilion. It is unlikely that the north-eastern pavilion was built simply to complete the symmetry of the entrance front. The plan (Fig. 80) showing the extent of the development of the house is based on the inventory of the contents of the house made in 1558 after Jacques des Ligneris's death, and it may show the full extent of the first owner's intentions, but it must have been foreseen that the gallery wing would have to be balanced at least by an arcaded screen on the right-hand side of the courtyard.

The step-by-step approach to building a large Parisian hôtel is perfectly illustrated in the first hundred years of this house's history, with separate masonry contracts for each of the major elements of the plan being agreed at different times, usually within months or a few years of each other, but

often the process took much longer and involved several owners using new architects. Only the main block was the subject of the 1548 contract,[24] and it was the fourth owner, Claude Boislève, who displaced the stable yard and had the courtyard completed and a pavilion built over the arch of a remodelled entrance front by François Mansart, work which was finished in 1661.[25] The story of French Renaissance architecture is full of unfinished grand designs and noble fragments of town and country houses begun 'with pleasure, continued with pain and completed in sorrow', but des Ligneris was one of the class whose buildings were built within their means and, according to De La Noue, tempted the nobility to their financial ruin.

The courtyard has its architectural variety, and it is known that there was another style employed for the original garden front of the corps de logis which was much admired, but inadequately described by Sauval.[26] It was of crépi or rough cast durable stone whose surface texture was certainly intended to create a 'rustic' effect, and our ignorance of its appearance is most regrettable. On a gateway, in Serlio's view, rustication created the impression of solidity or impregnability, and in this spirit it was used by Michele Sanmicheli in his famous city gates of Verona,[27] and by des Ligneris's architect on the entrance front. The façade seen by Sauval might have had rustication on the basement only, or extended up over the ground floor, or over all the floors, and if any of the windows and doors were framed by rusticated columns or pilasters with or without pediments, the back of des Ligneris's house would have been the first façade of the kind seen in France. Encasing classical façades in rustication became a 'leitmotif' for architectural popularizers such as Jacques Androuet du Cerceau later in the century.[28]

Successive owners made the Hôtel des Ligneris/Carnavalet the richest in sculpture of all sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Parisian private houses with reliefs on all four sides of the courtyard and on the outside. In France life-size figure sculpture was a feature of tombs, family chapels, church portals and some town halls, but des Ligneris's corps de logis is the earliest example of a private house with prominent allegorical reliefs, of Spring, Summer as Ceres, Autumn as Bacchus, and Winter (Fig. 81b). The fenestration of the corps de logis was designed like that of the Louvre to allow for sculpture, with panels of the same width as the windows, excluding their mouldings. The mason provided a perceptible extra thickness of stone in building the panels between the first-floor windows, and the reliefs were undoubtedly carved in situ by a sculptor using drawings by or imitating the style of Jean Goujon, and the intricacies of the drilling of Ceres' robes suggests a contribution by Goujon himself. In the spandrels' of the courtyard side of the entrance arch are two exquisite reclining figures of Fame and on the long, narrow, trapezoidal keystone, which breaks the moulding of the arch, is Authority standing on a globe and holding a bow and mace, all appropriate symbols for des Ligneris the 'parlementaire' and ambassador to the Council of Trent.[29] The tympanum

81(a)

Hôtel des Ligneris (Carnavalet).

Elevations of the courtyard front of the corps de logis .

(a) in 1847.

81(b)

Hôtel des Ligneris (Carnavalet).

Elevations of the courtyard front of the corps de logis .

(b) present state.

82

Hôtel des Ligneris (Carnavalet). Elevation of the gallery by Jean Marot, (1655/1657.)

sculpture and the lions (which originally were on the court side of the entrance screen) were added by the Carnavalet (Fig. 83) in the late 1560s, and the crude and tedious cycle of Elements and Virtues by Gérard Van Obstal on the left and right wings of the courtyard, entrance front and on the south side of the south-eastern pavilion were part of the works of Claude Boislève executed in the 1660s.[30]

The considerable losses of mid and late sixteenth-century Parisian town houses inhibits most generalizations on the contemporary influence of any one house whose appearance is known or which happens to have survived, invariably in a much altered condition. However, there are several reasons for believing that des Ligneris' house was much en vue during and after its first phase of building. His next-door neighbour to the north, Guillaume Barthélemy, 'contrôlleur de l'ordinaire des guerres', was building a house of equivalent quality in dressed stone, decorated with pilasters[31] (plots 47 and 32 in Fig. 18). The building contract of 6 March 1547 for the Hôtel Barthélemy specifies that the boundary wall on the right of the main part of the house was to be 'of the same thickness as the building which monsieur the président des Ligneris has begun'. The introvert nature of Parisian building is seen when reading the contracts for the Hôtel Barthélemy, especially in the paragraph giving the specifications for the corps de logis where the master mason is directed to imitate work at two recently completed houses in the capital which were known to the patron.[32] A most curious detail to be gleaned from these contracts is the mention that some

83

Hôtel des Ligneris (Carnavalet). Entrance gateway from the street. Present condition.

of the window frames were to be covered in paper, rather than filled with glass.[33]

On plots 20 to 22 of the lotissement of the Culture Sainte-Catherine (Fig. 18) in 1546 Jacques Le Jay, a notary and royal secretary, and in 1551 Pierre Le Jay, a royal councillor and Guillaume Barthélemy's senior as 'trésorier extraordinaire des guerres', agreed contracts for the building of one of the largest houses erected in the area.[34] The general organization of Le Jay's buildings was the same as des Ligneris' house, with a large corps de logis bisecting the site with no classical ornament, a gallery on the left hand side of the court with an open arcade with pilasters at ground-floor level, and kitchens relegated to the end of the gallery with a service door to the rue des Francs-Bourgeois.[35] The Hôtel Le Jay must have been designed by a man abreast of developments at Fontainebleau, for two months after the original contract of July 1546 its terms were altered to specify that the ground-floor windows of the corps de logis were to have dressed stone sills, those of the first floor were to have mouldings in plaster and the dormers were to be in brick, a colour accent which is reminiscent of the Hôtel de Ferrare.[36] The imposing house built by the Le Jays is not one of the invisible houses of Renaissance Paris which has to be imagined in the

84

Hôtel des Ligneris (Carnavalet).

Cellars under the corps de logis .

Nineteenth-century engraving.

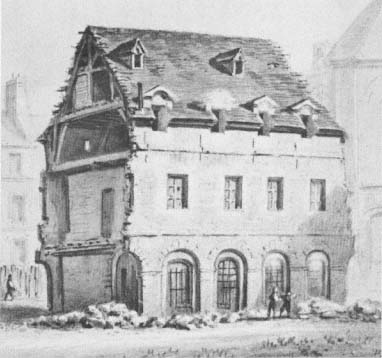

85

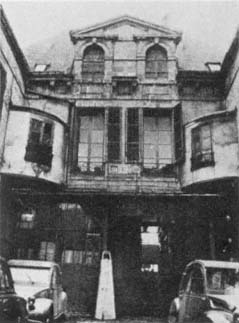

Hôtel Le Jay (d'Albret).

View of the roof and first floor from the south.

Present condition.

mind's eye from information in building contracts. It survives in the most decrepit condition with the garden filled with industrial buildings (Fig. 85). The details given in the original building contracts will be an important source of reference for the architect when the Hôtel Le Jay is restored.

More vivid for setting the Hôtel des Ligneris in an architectural context is the small courtyard of a house on the rue Beautrellis, which was a part of the lotissement of the Hôtel Saint-Pol, a house most probably built in the second half of the 1550s or the 1560s (Fig. 86). All four sides of the court are decorated with arcades of plain twin pilasters and finely detailed capitals, an unmistakable quotation from the ground floor of des Ligneris' gallery. Open or closed ground-floor arcades of pillars or columns were common features of the ancillary wings of town and country houses by the time of the last years of the reign of François I and the reign of Henri II, but it is the consistent and persistent use of pilasters at the Hôtel des Ligneris, the invisible Hôtel Barthélemy, the Hôtel Le Jay and the house on the rue Beautrellis, on the courtyard elevations of de l'Orme's Saint-Maur or Lescot's Louvre which should intrigue architectural historians, for in no other country at that time do architects appear to have been so preoccupied with using the bastard form of column. Some practical reasons for this phenomenon will be suggested below, but it is remarkable that no sixteenth- or early seventeenth-century French writer on architecture seriously concerned himself with the use or abuse of the pilaster form, and

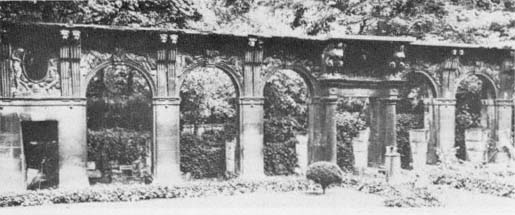

86

Courtyard arcades of a house n° 10 rue Beautrellis.

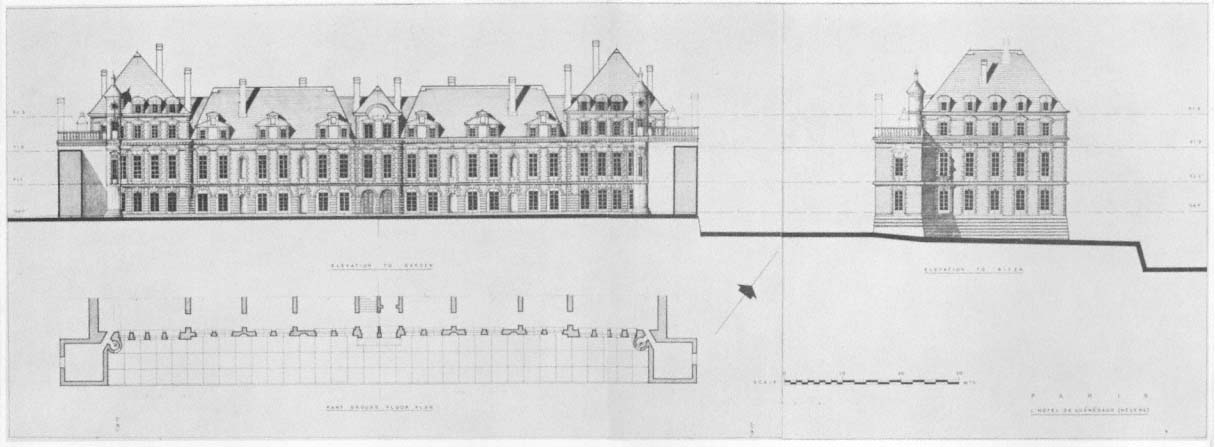

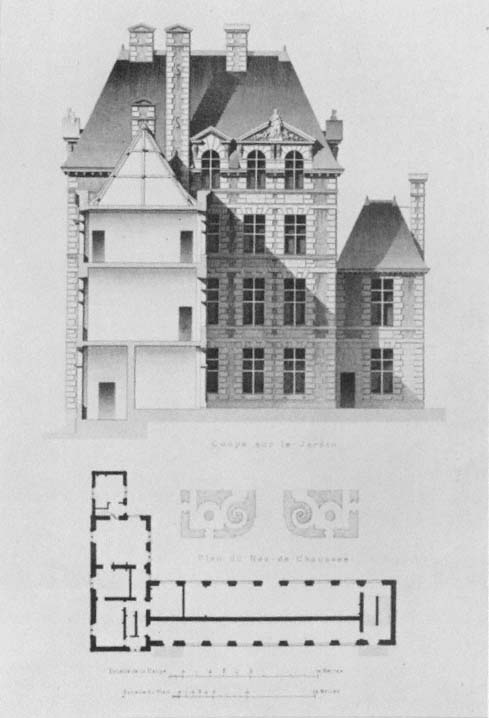

87

Hôtel du Cardinal de Meudon (de Birague, and later Chavigny).

Elevation of garden front and plan.

Reconstruction drawing by A. Don Johnson.

instead of taking into account a prominent characteristic of the architectural styles of their time they chose to labour over the intricacies of the proportions of the orders of columns.

On the largest site of the Culture Sainte-Catherine (inscribed 'Hôtel du Roi de Sicile' in Fig. 18) the uncle of the Duchesse d'Etampes, Antoine Sanguin, Cardinal de Meudon built a house during the early to mid 1550s shown in a reconstruction drawing (Fig. 87). Sanguin was one of the few from a long established Parisian family to build a prestigious new town house in the sixteenth century,[37] and the considerable rise in his fortunes was due in great part to preferment at Court through his niece, whose house on the Quai des Augustins had many stylistic similarities to Sanguin's (Fig. 49). Like the Hôtel d'Etampes, the Hôtel du Cardinal de Meudon was two storeys in height with an elaborate architecture of pilasters, and it is a pity that a comparison of their stylistic details cannot be

taken far because of the summary impression given in Sylvestre's engraving. The unknown architect of the Hôtel du Cardinal de Meudon was less gifted than Lescot in the design of arcades and the articulation of a façade with pilasters. The garden front of Sanguin's house owes more to the courtyard elevations of Ancy-le-Franc of the 1540s, which would have been known in Paris because of Serlio's contribution to the design, than to the elegance of Lescot's design of the Louvre. The system on the first floor, of window bays alternating with blank tableaux or panels separated by twin pilasters, is one which becomes familiar with the first of François I's châteaux in the Loire Valley at Blois and Chambord. If the participation of a Court architect in the design of the Hôtel des Ligneris is strongly suspected, Sanguin's architect was either not in touch or not in sympathy with the architectural thought and styles being discussed in aristocratic artistic circles of the early 1550s.

The plan of this house is unusual, but it is quite legible with its twin galleries on the ground and first floors connecting the west and east pavilions, the public and the private parts of the house. The option of a central staircase was open to the architect planning a building on a site as spacious as Sanguin's, but the main staircase was placed on the left-hand corner of the entrance court. This western pavilion, on the right-hand side of the drawing, had reception or public rooms on both floors, and the private apartments were at the opposite end of the galleries, with their own entrance from the court and a smaller staircase. The use to which the galleries were put remains conjectural. They were narrow and as far as we know without fireplaces, and they might have been intended as nothing more than richly-decorated corridors, for it is difficult to imagine banquets or dancing taking place in a space only four metres wide. Sanguin died in 1559 and is supposed to have left the house unfinished, but the Chancellor René de Birague who bought the property in about 1573 is known to have entertained Henri III in a gallery where he set up a magnificent display of plate of over a thousand pieces, most of which was broken by servants. That gallery might have been in the main block or in the one which Birague had built in the garden which is wider.[38]

A description of the styles of haut-bourgeois and aristocratic buildings of the second half of the sixteenth century in Paris is almost wholly centred on the small area of the Culture Sainte-Catherine. This part of the Marais in its first phase of development in the late 1540s and 1550s attracted the class spoken of by De La Noue and Dallington, and during the late 1550s, 1560s and 1570s there was a small but significant immigration into the area of nobility and aristocracy who bought and enlarged hôtels begun by the 'Lawyers and officers of the King's Money'. The Carnavalet bought des Ligneris' house and the Montmorency bought the Hôtel Le Jay and the Hôtel Barthélemy.[39] Some aristocratic building took place on the Left Bank during the troubled 1560s and 1570s,[40] but it was close to the Louvre in the 'quartier Saint-Honoré' and in the parish of Saint-Germain

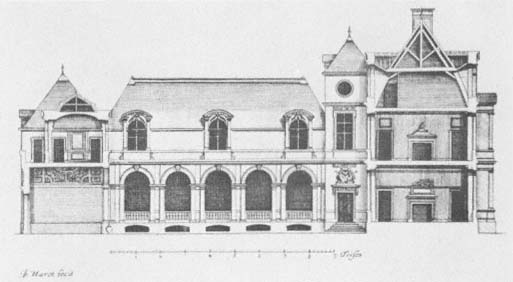

88

Hôtel du Faur. Elevation of north-facing gallery wing on the courtyard.

Engraving from Albert Lenoir's Statistique Monumentale du Vieux Paris of 1867.

L'Auxerrois that, as the notarial documents show, there was the greatest amount of building activity by leading personalities at the Court of Henri III during the 1580s. The architecture of just one of these houses is known (Figs 117–120).[41]

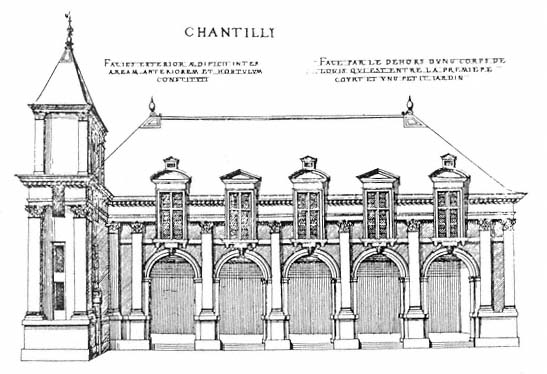

For the 1560s the solitary aristocratic hôtel which can be illustrated is the Hôtel du Faur (Figs 88–90) which is unlike any other known Parisian private house of the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries, and has been described as Toulousian rather than Parisian in style.[42] The patron, Jacques du Faur, was of an old and senior Toulouse family, 'la première maison de Robbe Longue en France', a leading jurist, member of the conseil privé of Charles IX from 1565 and the most trusted colleague and adviser to the Chancellor de l'Hôpital. The ground-floor arcade, now at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, is inscribed with the date 1567. On the eastern edge of the city on the Left Bank on the rue des Bernardins, du Faur built his unusual house in a quarter not associated with aristocratic building during the period.

89

Hôtel du Faur. Detail of gallery elevation from Lenoir.

90

Hôtel du Faur. Ground-floor arcade, now at the Ecole des Beaux Arts.

The elevation of the wing, recorded for Lenoir's Statistique Monumental de Paris before the destruction of the house in 1830, is a strange stylistic hybrid with different and contrasting decorative systems used for each of the four floors. Inspired by Goujon's work on the Louvre the ground-floor arcade has spandrel reliefs of Victories, allegorical figures of Fame, Captives and Peace reigning over the central doorway. It was the screen of a cryptoporticus in which Niccolo dell'Abbate painted an elaborate fresco cycle of pastoral mythological allegories. Dell'Abbate was the leading Italian painter in Paris, working for only the very great and powerful of the Kingdom, for the Constable Anne de Montmorency in the gallery of his largest Parisian house and in the chapel and duchess's room at the Hôtel de Guise.[43] In its sculptural and painted decoration the Hôtel du Faur was at the heart of Court art of the late 1560s, with patriotic and pastoral symbolism wholly in keeping with the literary tastes developed by Court poets. A member of the du Faur family, Guy du Faur de Pibrac, who was one of the most famous writers of pastoral verse in late sixteenth-century France, stayed in the house in 1576, and he may well have been the iconographer or inspiration of the sculpture and painting.[44] More than one literary figure is known to have taken an active role in devising costly sculptural programmes for the houses of proud but not always rich aristocrats.[45]

The wing of the Hôtel du Faur published by Lenoir ran from east to west facing north and at right angles to the street, and resembles in neither form nor detail the evolving 'classic' town house such as the Hôtels des Ligneris/Carnavalet or Le Jay. The Hôtel du Faur, on the edge of Paris, might have been conceived as a suburban or semi-rural retreat away from the populous parts of the city, as is suggested by its pastoral imagery in the cryptoporticus, where an eccentric and individual architecture could have

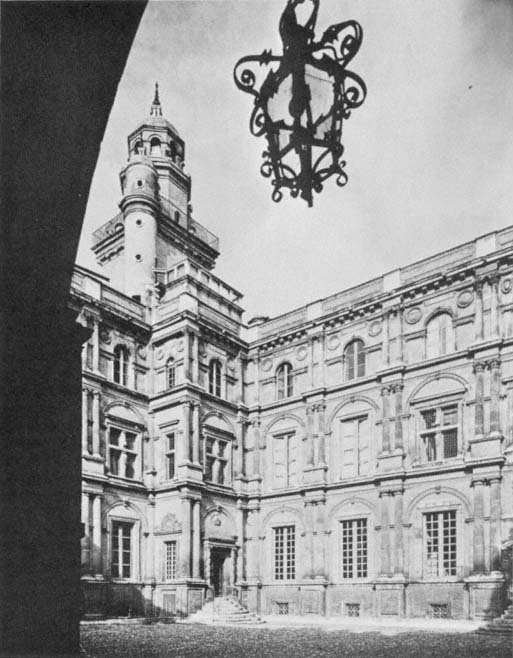

91

Hôtel d'Assézat at Toulouse. View of the courtyard.

been part of both its charm and sophistication to the eyes of contemporaries. The variety in the treatment of each floor is puzzling since Lescot had shown a way of coherently articulating or unifying in the vertical a richly decorated façade with the use of pilasters. At Toulouse the leading local architect Nicolas Bachelier concocted a unifying system of incorrectly proportioned Doric, Ionic and Corinthian applied columns for the three-storey courtyard elevations of the monumental Hôtel d'Assézat built between 1552 and 1562 where the influence of both Serlio and of Lescot's Louvre is clear in the combinations of shallow arcades and twin columns (Fig. 91).

As the engraving of the Hôtel du Faur's elevation looks so little like that of any other known Parisian sixteenth-century private house in form or detail it is tempting to ascribe its design to an architect from the southwest, where a variety of classical architectural styles were developed by men of letters and master masons which sometimes were more distinctly Italianate, with columns and loggias of arcades, than anything seen in the capital. The idea has to be questioned, for the 1560s was remarkable for flamboyant, classical, but hardly Italianate, architectural design by architects and architectural popularizers associated with the Court. De l'Orme's design of the Tuileries (Figs 124–125) was revolutionary in style with every conventional architectural member and small decorative feature remodelled, revised and combined in new ways. Androuet du Cerceau's albums of drawings of 'bastiments à plaisir' datable to the reign of Charles IX (1560–1576) are rich in fanciful designs, and is evidence of a short-lived fashion for bizarre combinations of exotic sculpture, oddly-proportioned orders and rich decorative textures on friezes and consoles, with rough and smooth rustication. The precise architectural context of the Hôtel du Faur remains to be defined, and the identification of its architect would be a great step forward. Closely-spaced windows on the first floor might have been chosen because the wing faced north and had no south front, to harmonize with the width of the cryptoporticus arcade, which obviated the need for a vertical order with a finely-observed Doric frieze being the only classical feature. The decorative system of the second floor can be described but cannot be interpreted. The meaning of the twin herms on fluted podia flanked by bows is obscure, but it is not likely to have been a decorative motif used at random; the mouldings of the windows on this floor, with their lugs and curved architraves, are quoted from Lescot's Louvre. The dormer windows were flanked by herms with stocky trapezoidal podia capped by triglyphs supporting broken alternating triangular and shallow curved pediments. By the 1560s it had become common practice to give the same height to the ground and first floors, but the proportions of the second floor and the dormer storey were not legibly related by a simple ratio to the heights of the floors below. The Hôtel du Faur is the most perplexing building in the history of sixteenth-century Parisian architecture.

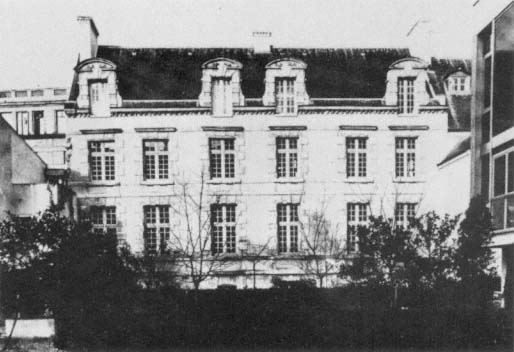

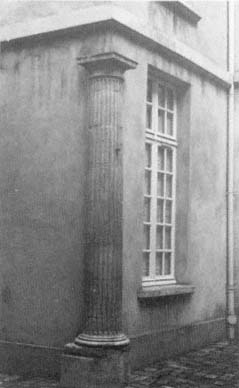

92

House of Philibert de l'Orme on the rue de la Cerisaie.

Plan by Vaudoyer.

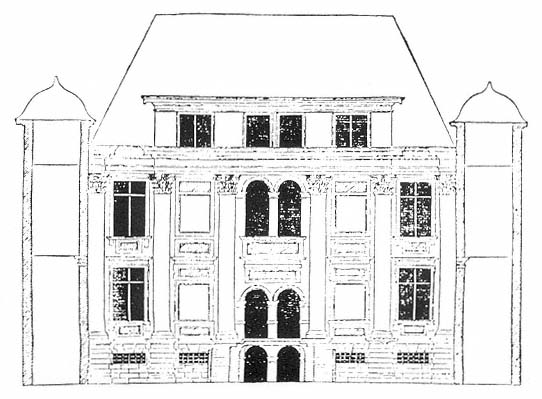

The best documented scene of haut-bourgeois and aristocratic building in the late sixteenth century is still on the regular rectangular plots of the lotissements in the east of the city on the Right Bank, and they provide a convenient framework for descriptions and analyses of similarities and variety in planning and styles of elevations. In his Architecture of 1567 in stark contrast to his expert discourses on the technicalities of building, the fine points of the orders and his accounts of his most prestigious country house commissions, Philibert de l'Orme published woodcuts illustrating the house which he had designed and had built for himself about ten years earlier (Figs 92–94) on one of six long but narrow sites (about 16 metres) on the north side of the rue de la Cerisaie, a part of the lotissement of the Hôtel Saint-Pol (Fig. 17). The plan of the house, with corps de logis set back from the street between a forecourt and a garden at the back, is now familiar, but its austere appearance might be thought surprising from a man of de l'Orme's wealth and architectural culture, but as always he had good, clear, practical reasons to recommend his composition to his readers. De l'Orme is the best guide to the house and its architecture.

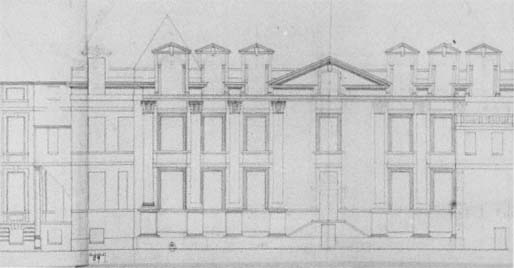

93

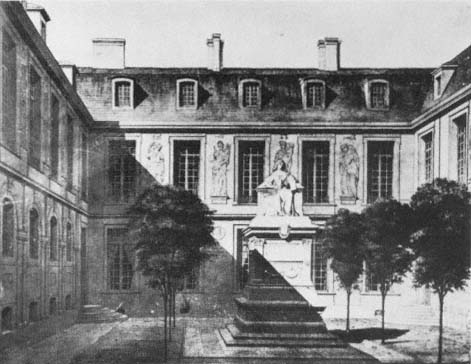

House of Philibert de l'Orme. View of the courtyard from his Architecture of 1567.

Some might be thinking, after having read what I have written on the façades of buildings, to show the arrangements of windows, that I want to oblige them, or even compel them, to put columns and pillars on the façades of houses, which I have not claimed at all: for all those who wish to spend modestly have no need of such refinements and enrichments on the façade of a house, just as their resources are unable to meet such great expenditures: but it is quite true that the composition and order of windows, which will be set in the façades of houses, ought to conform

94

House of Philibert de l'Orme. Elevation of the garden front from his Architecture of 1567.

to such proportions and measurements, so that which one sees on one side might be seen on the other without columns or pillars, which is the manner sought, and it can be seen clearly in the next illustration (Fig. 93): in it I put, on the first floor, windows with mullions and transoms only: and on the second I show you how you might have designed between these windows, courses of stone, without the forms of pillars, capitals and other such things: and further windows are set into the roof and, should you wish, can be in dressed stone, in the rustic manner, or even quite plain, as the corners of the building can be treated. You see as well at the entablature of the whole building, on which rest the joists and the dormers, in case anyone should put cornices there, I have put mutules there in the form of scrolls to decorate and to make the house more attractive. I offer you also in this illustration square pillars

connected by arches to create a peristyle below and a gallery above, all without columns, nor pedestals, capitals and cornices: this is to show how the learned and expert architect can devise an elegant building, without great expense, that will look as good as others which are much more elaborate: so you can see and judge in the next illustration.

Since I am dealing with this purpose, I will finish by showing you the other side of the house, which faces the garden (Fig. 94). In the middle of it I have put a round tower, whose first (ground) floor serves as a chapel with a gallery in front of it with openings and windows of a different kind from the others: for they are curved, and do not have a height greater than their width: I have given them such great width to make the gallery more pleasant: nevertheless it is graceful and of great beauty just as it is: but it is much more so when the original is seen, than can be gleaned from the representation of it which you will see following. On the second floor of the tower is a very solid closet, being vaulted in dressed stone below and above, and well secured. On either side are other closets and terraces: and behind are the main living quarters of the house: all of it being, whether windows, entablatures or dormers, done (as you see in the illustration) in thoroughly good materials with great competence, as much in the cellars as in other places. You should know that all this is as it has been done for myself, being my own home, as you see it in the preceding and following illustrations.

Philibert de l'Orme was too summary in justifying why his simpler classical and unclassical forms are to be seen as beautiful, but his insistence that good architecture can be achieved within strict financial limitations is a result of his experience in designing and organizing large and small building programmes. At Anet, for Diane de Poitiers, Philibert did not launch the building of the whole scheme at the beginning, but made sure that the corps de logis was complete before passing contracts for the less essential entrance pavilion.[46] His business-like approach shows a clear sense of priorities in proceeding with building, and many apart from des Ligneris followed his advice before the publication of his book, and probably consulted him. In the text accompanying the woodcut showing the wing which he had hoped to build to close the courtyard of his own house, on the rue de la Cerisaie (Fig. 96), he mentioned his activity as a designer of middle-class houses, all of which have disappeared, but which can be read of in documents.[47]

In unambiguous terms de l'Orme told his readers that intelligent planning and good building could produce architecture to be admired, without any need for elaborate classical trappings. The house built about 1576 for Médéric de Donon, sieur de Châtres en Brie and of Loribeau, a Royal Councillor and Controller General of the King's buildings, on plots 57 and 50 of the Culture Sainte-Catherine, is a perfect example of the influence of de l'Orme after his death in 1570[48] (Figs 97–99). The site is

95

House at 20 rue Ferdinand Duval in which Philibert de l'Orme was staying in 1546.

(Compare with the design of the garden front of his own house.)

96

House of Philibert de l'Orme.

Unexecuted street front on the rue de la Cerisaie, from his Architecture of 1567.

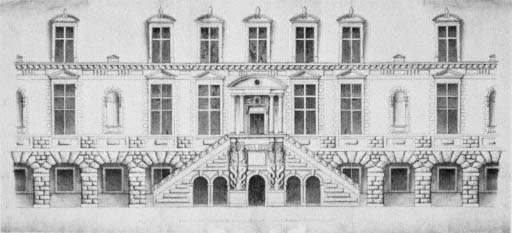

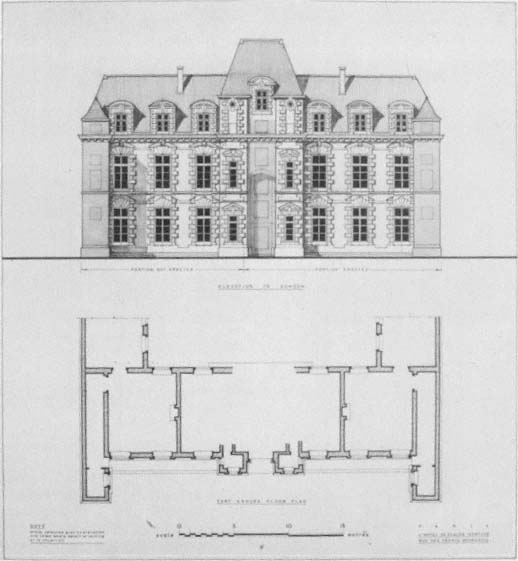

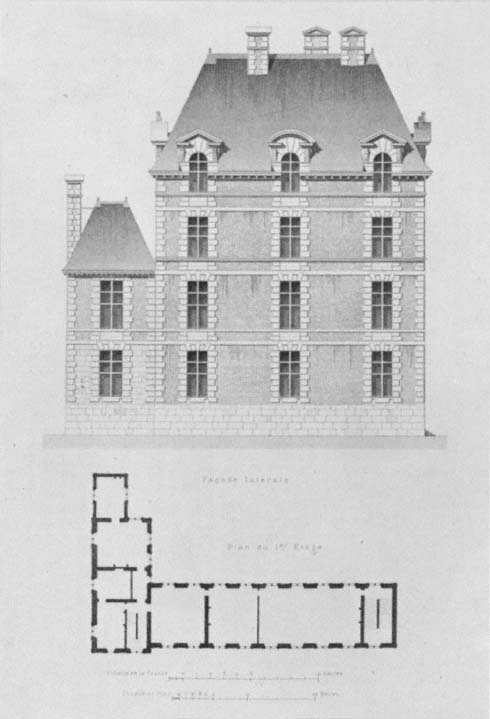

97

Hôtel de Donon. Couryard front of the corps de logis and plans.

Reconstruction drawing. Jean-Pierre Babelon, inv., Jean Blécon, del.

99

Hôtel de Donon.

Courtyard front of the corps de logis .

98

Hôtel de Donon. View of the roof of the corps de logis on the garden side.

only slightly wider than was de l'Orme's, the corps de logis is in the form of a pavilion built well back from the street, but leaving room for a private garden in the western half. The site for Donon's house was much less spacious than the neighbouring Hôtel des Ligneris/Carnavalet, but the Hôtel de Donon was planned and organized with few differences. In the basement of the main block were the kitchens and a servant's hall, much closer to the reception rooms and private apartments than at the more prestigious Hôtels des Ligneris/Carnavalet or Le Jay. Otherwise the 'classic' formula of the plan of des Ligneris's house is repeated, with the stables to the right of the entrance, a gallery on the left and staircases in the left- and right-hand corners of the courtyard. The main block has clear rhythms, two floors of equal height with a fenestration of demie-croisée, croisée, croisée, demie-croisée . This clarity and balance of the elevations was made more imposing by the tall pitched roof, which created an extra floor, but when seen from below from the courtyard is less dominant than in a drawn elevation (Fig. 99). Pillars or some other form of simple classical decoration were probably included in the design of the gallery, as personally recommended by de l'Orme as not too expensive an embellishment, and a further affinity of the Hôtel de Donon with the Hôtel de l'Orme is in the limitation of classical ornament to the entablature and dormers of the main block. The entablature of the Hôtel de Donon has de l'Orme's scroll brackets to support the cornice. On the courtyard side the composition of the dormers is unpretentious but sophisticated; the arches of the windows are made up of clear solid masses, pillars, block capitals, broad arch mouldings and projecting keystones. The broad triangular pediment joins

the two dormers, but in breaking the base moulding of the pediment the architect artfully gave to each dormer its own cornice. On the garden side (Fig. 98) the two main dormers over the croisées are separate with their own pediments, and to echo the proportions of the windows below half size dormers were placed above the demie croisées on the left and right of the main pair.

Only where the width was available could systems of columns or pilasters be used intelligently and to good effect. De l'Orme was keenly aware of the unsuitability of the narrower sites on the lotissements for the demands of classical styles which required width to be properly articulated. It would be interesting to know if Bernard de Girard had a particular house in mind when he wrote of interiors being made ugly in order to satisfy the requirements of classical embellishments on the exterior. The Hôtel de Donon is a prime example of a town house where the application of classical decoration would have been to its detriment, and which should have pleased those writers of the 1560s and 1570s who scorned architectural fashion.

The next house to the north of the Hôtel de Donon (plots 56, 51, and 52 in Fig. 18), now known as the Hôtel de Marle, has been remodelled on several occasions, but there are reasons for believing that the main part of this substantial house is mostly a building of the late 1560s or 1570s[49] (Fig. 100). On a north—south axis, with a basement, an enfilade of three rooms on two floors of equal height and an attic storey, the corps de logis bisects the site between courtyard and garden in the familiar way. In the course of its restoration during the 1960s a false roof was removed to reveal the joinery of the admirable hipped roof 'à la Philibert de l'Orme' now to be seen as it was intended with its gentle ogee profile.[50] The symmetry of the garden elevation has been upset by the piercing of a door and window, the second bay from the left. It is possible that the present plain appearance of the house does not represent the full extent of the intentions of either of the sixteenth-century owners of the Hôtel de Marle, for it can be imagined how the wide, bare areas of wall between the windows might have been filled with two tiers of panels framed by pilasters like the Hôtel du Cardinal de Meudon, or even a system of giant pilasters as Diane de France, Duchesse d'Angoulême embellished an existing corps de logis which will be discussed below (Figs 111–114). None of the pre-revolutionary guides or histories of Paris mention the Hôtel de Marle as having a classical appearance. Many of Serlio's and du Cerceau's models show only basic dispositions of plan and elevation, and left decorative refinements as a matter for further discussion between a patron and his architect or master mason.

When De La Noue wrote of houses begun 'with pleasure, continued with pain, and completed with sorrow,' he was prophesying the fate of two, if not of three, of the most interesting Parisian buildings of the late 1570s and 1580s, the Hôtel de Nevers (Figs 101–103), the Hôtel Mortier

100

Hôtel de Marle. Garden front.

(Fig. 105) and the Palais Abbatial of Saint-Germain-des-Prés (Figs 107–109) which were never completed. The builder of the Hôtel de Nevers was Louis de Gonzague (1539–1595), one of the most interesting personalities and patrons of the arts and sciences of late sixteenth-century France; a serious study on Louis de Gonzague would bring rich rewards not least on Franco-Italian literary and artistic relations. Nevers' secretary was Blaise de Vigenère (1523–1596) a distinguished antiquarian, a philologist, chemist, historian, art historian, the first theoretician of translation and the only contemporary to leave a critical account of French artists of the sixteenth century.[51] The Hôtel de Nevers was the subject of much contemporary comment and admiration, and de Vigenère mentions one special feature of his patron's house, a vault built by men brought from Italy by Louis de Gonzague, which was ' . . . aussi platte et plus grande que celle des Thermes de Caracalle, . . .' De Vigenère certainly exaggerated the scale of the vault, but it must have been very imposing and wholly new to Paris. If no record of the appearance of the Hôtel de Nevers had survived, a

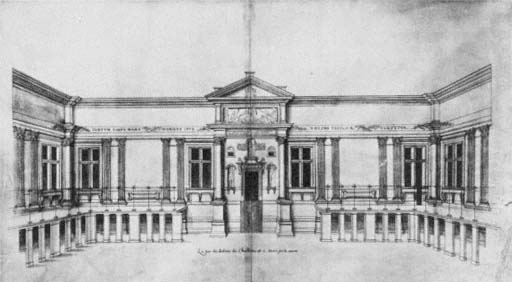

101

Hôtel de Nevers. Elevation of garden (east) front, and of the north side of the angle pavilion facing the Seine.

Reconstruction drawing by A. Don Johnson.

building as thoroughly French in its elevations and silhouette would be thought improbable.

Sylvestre's small copperplate engravings give a vivid impression of how the north pavilion of the Hôtel de Nevers was the prominent feature of its part of the Left Bank. Gonzague chose the site because it was close to the newly begun Pont Neuf connecting the north and south banks of the Seine across the western end of the Ile de la Cité (Fig. 103), and was directly opposite and visible from the 'pavillon du roi' of the Louvre. His intention was to build the largest private house within the city walls, and with the lotissements filled by the late 1570s, the availability of the last remaining of the large medieval royal properties, the Hôtel de Nesle, was an opportunity to build an expansive house and a landmark. Louis de Gonzague was not amongst those who bankrupted themselves by building, for his personal fortune was already considerable before he married Henriette de Clèves the richest heiress in France of her day, but the complete project for the Hôtel de Nevers anticipated the full and uncontested title to the whole site and the acquisition of more ground for the south pavilion. Nevers

102

Hôtel de Nevers.

Gallery, detail of an engraving by Poinsart.

103

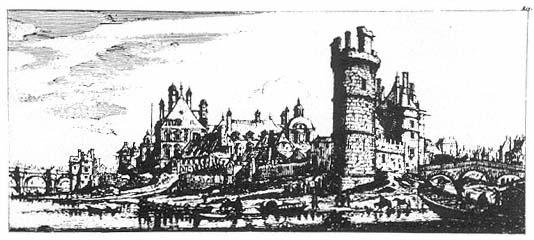

Hôtel de Nevers. View of its setting in the mid-seventeenth century. Engraving by Israel Sylvestre.

might have been hoping to see his initiative followed by others building fine houses nearby, to transform a dilapidated quarter of the city. After decades of litigation with the municipality over rights to the walls and adjacent ground, the Nevers family thought of demolishing the house, and were very pleased to sell it with all its troubles in 1642.[52]

Begun by 1582, the architecture of the corps de logis and of the gallery at right angles to it on the quayside was of great significance for royal and aristocratic building in Paris over the following forty years, and especially influenced the architectural thought of the avid builder, Henri IV. The corps de logis of the Hôtel de Nevers was not the first brick building in Paris,[53] but it was the earliest example in the city of a brick and stone style developed in the Ile de France during the 1540s and 1550s. The name of the architect is not known, but the refined use of quoins points to a Court architect, either the aged Pierre Lescot or more probably Henri III's favourite architect who had been trained by Lescot or who had been his assistant, Baptiste Androuet du Cerceau.[54] Lescot's reputation is based solely on his design of the Louvre, but he was also the designer of the Château de Vallery built from 1549 to 1555 (Fig. 104), which has been singled out by one recent writer as representing several steps forward in brick and stone architecture in France.[55] The probable link of the style of the Hôtel de Nevers with the architectural thought and styles of Pierre Lescot creates an historical impasse, for the loss of the manuscript of his treatise with its ' . . . plants & pourtraits des plus superbes & magnifiques palays . . .' and the diversity of his style in reliably attributed and documented buildings, at the Louvre, Vallery and the entrance gate of the Hôtel des Ligneris/Carnavalet, makes it impossible to judge or to describe the sources and motives for the use and combination of decorative

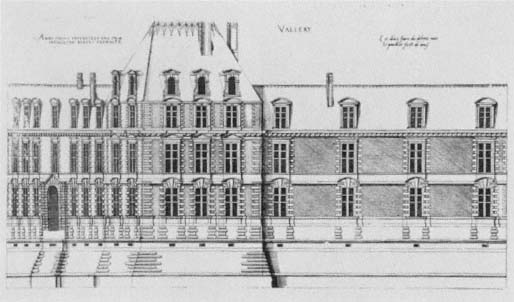

104

Vallery. Outside elevation of the angle pavilion.

elements in his elevations. The proportions of the angle pavilion of Vallery are analogous to those of the 'pavillon du roi' of the Louvre (Fig. 61), but the decoration of Vallery using no order of column or pilaster, with rustication breaking the stone mouldings of the windows and rusticated keystones interrupting the base mouldings of the pediments is the sort of architectural solecism which was inspired by the work of Giulio Romano at Mantua, and it is appropriate that this architectural manner was used for the Parisian palace of a Gonzaga.

The arrangement of the components of the garden front of the Hôtel de Nevers, with its narrow central-staircase pavilion, twin flanking blocks and large-angle pavilions, is a composition of masses typical of French country-house architecture of the reign of Henri III, especially of houses by or attributed to Baptiste Androuet du Cerceau at Fresnes and Liancourt.[56] It was his custom, following the tradition of the châteaux of François I, to give each portion of the elevation an individual steeply pitched roof. As an essay in rustication the Hôtel de Nevers was less adventurous than Vallery, with quoins rarely breaking a moulding, but the architect was obviously interested in creating variety in the design of the decoration for each floor. The ground floor has a blind arcade between the angle pavilions, and there are three different treatments of the tops of the windows and the niches across the full width of the ground floor. On the first-floor curved pediments are used for the piano nobile, and above the main cornice the variety becomes more deliberate, with twin dormers capped by alternating

broken triangular and curved pediments, their breaks being made by triangular pedimented tabernacles in the curved pediments, and curved pedimented tabernacles in the triangular pediments. Nevers' twin dormers should be compared to those of the Tuileries and that of the Hôtel de Donon. The attic storey of the angle pavilions of the Hôtel de Nevers have quoined windows with only the upper moulding of a shallow triangular pediment, whilst the dormers above are given fully-fledged curved pediments. Pediments are the only decorative motif from the repertoire of the orders of classical architecture to be adopted in this style of brick and stone architecture.

The walls of the gallery were built, but it was never roofed.[57] Its elevation was in complete and deliberate contrast to the corps de logis , with giant pilasters supporting alternating curved and triangular pediments. Henri IV was greatly impressed by Nevers' building, and joked that once the house was finished he would be coming to stay. The western half of the Grande Galerie of the Louvre (Fig. 135) across the river imitated the style of Nevers' gallery on a grander scale. The variety and disparity of the architectures around the garden of the Hôtel de Nevers is much in the spirit of de Vigenère's counsels to patrons and builders, such as his view that ' . . . l'ordonnance et disposition d'un bastiment . . . dépend de la fantaisie de l'architecte, qui est comme un nouveau créateur quant à la forme et figure'. In numerous comments scattered through his writings de Vigenère argued, in a vein like Vasari praising the creativity of Michelangelo's architecture, that the ancient rules of architecture are of value, but should not be taken as final, that the architect must have a particular talent that goes beyond anatomical knowledge, and that he must transcend conventions in order to invent. De Vigenère placed the talented and original architect at the summit of his artistic hierarchy. Although his urgings of architects to think for themselves, and not to be cowed by rules or by the example of others, are not wholly new in architectural writing, the designing of the Hôtel de Nevers must owe something to his notions of experiment and freshness of approach to architecture.

The example of Nevers' palace consolidated the fashion for brick and stone building, or at least for quoined elevations in the architecture of haut-bourgeois and aristocratic town houses. The first fully-evolved example of this influence is seen at the Hôtel Mortier, on the rue des Francs-Bourgeois just west of the developments on the Culture Sainte-Catherine (Fig. 105).[58] The special and only all'antica feature of the garden façade of this house is the game played with the pediments over the windows. Vertically, the pediments at ground-floor level start as broken end stubs, above on the first floor they appear as curved without a base moulding and bisected by a keystone, and on the dormers they are full-curved pediments with only the base mouldings broken by a keystone. Read vertically the pediments are progressively completed, whilst on the advanced bays the system is varied and inverted, with full triangular

105

Hôtel Mortier. Garden front. Reconstruction drawing by A. Don Johnson.

pediments with broken-base mouldings on the ground floor, fully broken curved pediments on the first floor, and oculi on the attic. In the manner of the ground floor of Vallery, the windows have superimposed quoins.

The date of the building of Claude Mortier's house can only be given as somewhere between 1572 and 1586, but it is probable that the design and building took place during the latter part of the period. Mortier was of the same class of men who had built their houses on the Culture Sainte-Catherine in the late 1540s, a notary and Royal financial secretary.

106

Hôtel de Savourny. View of corps de logis . Present condition.

The reconstruction shows the garden façade as it would have been completed, for only the central bays and the four bays to the right were built. The Hôtel Mortier might have been begun 'with pleasure' in anticipation of completing the design on the next plot to the east, but for unknown reasons this fine composition was never more than a noble fragment of a full scheme which would have been as large as any hôtel in the Marais. Proof that the Hôtel Mortier was the building 'en vue' in the Marais of the 1580s is found in the contracts of 1586 for the building of the Hôtel de Savourny on plots 59 and 48 of the Culture Sainte-Catherine (Fig. 106), where the mason was instructed to build dormers ' . . . semblables à celles . . . de M. Mortier . . .' and the carpenter who was to make the doors for the gateway to the street agreed to copy those of the Hôtel Mortier.[59] Carlo Savornini or Savourny was a royal equerry, and like Gonzaga he built his more modest house in the current Parisian fashion, with a decoration of rustication less refined than the bevelled blocks on the garden front of the Hôtel Mortier, void of columns or pilaster, and without pediments.

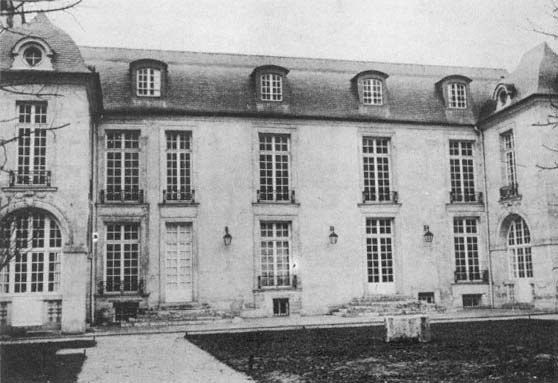

The only intact survivor of a building in the brick and stone style from the reign of Henri III in Paris is the Palais Abbatial of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, built in 1586 for Charles de Bourbon, the pretender to the throne

107

Palais Abbatial of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. East front. Engraving from Berty.

108

Palais Abbatial of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. North front. Photo: Inventaire Général.

during the War of the League as Charles X, and designed by the master mason and architect Guillaume Marchant.[60] Both the outward elevations and those facing the garden are in the rustic idiom (Figs 107–109) and the analogies in its decorative details with the Hôtel de Nevers and the Hôtel Mortier are numerous. Marchant gave the Palais Abbatial an imposing gable for its angle pavilion like that at Nevers, and designed a revised

109

Palais Abbatial of Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

Section and east wing from garden side.

Engraving from Berty.

110

Hôtel de Gondi (Condé). Bird's-eye view by Lespinasse.

version of Nevers' pedimented twin dormers which cut and fragment the main cornice in the manner of the Hôtel d'Angoulême (Figs 112–113). Unlike Nevers and Mortier the Palais Abbatial pediments are used exclusively on the dormers, with alternating triangular and semi-circular pediments with broken base mouldings on both sides of the north wing. Looking at the elevations of the eastern block of the Palais Abbatial, it is difficult to believe that the building which we see today, begun in 1586 and finished about 1590, can represent the full scheme envisaged by Guillaume Marchant or Henri IV's uncle Charles de Bourbon. It is possible only to conjecture, but the garden front of the east wing in particular looks like a portion of a longer composition (Fig. 109) with one or two more large pavilions to be added. It was not uncommon for patrons and master masons to sign building contracts for half, or less, or more, of a project agreed in the form of a drawing or model. The sixteenth-century building history of the Louvre is the classic example of this procedure, but such caution did not always lead to the satisfactory completion of houses. As compensation, since its cleaning in the 1970s, the Palais Abbatial of Saint-Germain-des-Prés is the earliest well-preserved building in Paris where the polychromy of red brick and sandstone can be admired, and it shows the style fully developed before its apogee under the auspices of Henri IV with the place Royale (des Vosges) and the place Dauphine.[61]

The story of aristocratic building on the Left Bank during the sixteenth

111

Hôtel d'Angoulême. View of garden front. Engraving by Israel Sylvestre.

century is even more fragmentary than that of those parts of the Right Bank, les Halles or the parish of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois, which have been cleared or redeveloped in every succeeding century. Only a small number of the very wealthy and powerful chose to build on the Left Bank, amongst whom were the Gondi who accumulated a large holding to the north-east of where the Odéon now stands. The buildings seen at the left in de Lespinasse's drawing (Fig. 110), showing the considerable additions by François Mansart and Jacques Gabriel for the Condé in the seventeenth century, are thought to be those built for Jérôme II de Gondi during the late 1570s or early 1580s.[62] The narrow central passage and staircase pavilion at the end of the courtyard is of similar form and proportion to that of the Hôtel de Nevers, and the window mouldings show the persistent influence of the Louvre, but the curious, illiterate use of classical ornament on the central pavilion is surprising on the house of a family so closely linked to Catherine de Medici.

Back on home ground on the Culture Sainte-Catherine there stands the lone surviving masterpiece of a truly classical late-Renaissance Parisian town house, the Hôtel d'Angoulême, on plots 17 to 15 of the lotissement on the south side of the rue des Francs Bourgeois opposite the Hôtel des Ligneris/Carnavalet (Figs 111–114). In 1584 Diane de France, Duchesse d'Angoulême, the natural daughter of Henri II, bought the property.[63] Before a satisfactory analysis of the Hôtel d'Angoulême can be written, the

112

Hôtel d'Angoulême. Elevation of the garden front. Drawing by Robert de Cotte.