TWO

BUILDING A NATION OF CITIES

3

The Engine of Private Enterprise

New York 1820-70: commerce, canals, and sweatshops

The Typical American City Dweller is a commuter. He lives in one place, and from there he drives or takes a bus or subway to another place, where he works. For him there are two cities: a city of homes, a city of jobs. In daily alternations he delineates two of the essential elements of city growth, for it is the interaction between jobs and homes that shapes the city. The jobs pay for the houses and in part determine their location, but in part the location of jobs is governed by proximity to the houses. The interdependence speaks of much of the growth and development of our cities. This unity between commonplace experience and basic urban structure holds out great potentialities for the democratic control of our metropolitan world, but they have remained largely unrealized. The difficulty is that most citizens see themselves as men and women coping with the city and not as participants in its building.

The sheer size and extent of our cities overwhelms us. The interminable streets of houses, stores, offices, and factories, the incongruity between slums and suburbs, the intimidation of giant office towers, the flood of traffic, the infinity of government offices engender a sense of powerlessness. Such a sense has nurtured a depressed and defensive civic consciousness. We vote, but not so often as our ancestors; we turn out, a few of us at least, to defend our neighborhoods or our children in public hearings and school meetings; we join organizations, if it is required or if it is the custom of the place. But neither the politicians nor

the officers of our organizations seem able to do much to assist the family budget or to combat the dearth of good jobs, the decay of the neighborhood, the danger on the streets, the needs of a difficult child, the disaffection of young people, or the isolation of aged relatives. We do have a strong sense of home, even though many of us move from block to block or from subdivision to subdivision, and that sense can be touched by personal tragedy or by organized appeals for church and charity. It is nevertheless a circumscribed feeling and only a partial public manifestation of an essentially private life. For the most part we learn to take the job as it comes and the city as we find it.

A deep pessimism underlies this sort of adaptation to modern city life. We comfort ourselves in our helplessness by repeating the bromide that the system is at fault, that it somehow seems to work against people, not for them. On the job no one cares for good work, no one looks out for the other guy, no one wishes to take responsibility. And for all the years at school, the raises and fringe benefits, and the household gadgets, a comfortable home and a decent neighborhood are becoming harder and harder to find and to manage.

This commonplace reasoning from everyday experience is sound enough; it is the wisdom of people trying to cope with a hostile world. But it is self-regarding and self-defeating, and precludes any possibility of understanding the meaning and consequences of the catchall we use to express the generality of our experience the system. We speak often of "the system," by which we mean a set of nearly all-powerful outside forces that control our jobs, our homes, and our lives. Neither we nor our politicians are apt to speak of the system in terms that suggest what we might do to change it.

The very fact that an urban system exists, that we do not all suffer at random but are harassed by predictable, repeated, and identifiable interactions, creates the possibility for intelligent action and points to the hope for change. Since the thrust of our urban history has been toward ever more inclusive organization of our cities and ever greater integration of our national economy, it is clear that we now live in a period—as opposed to earlier, more loosely structured times—when problems connected with homes and jobs can be effectively politicized. We can reasonably expect that out of the conflicts that arise over the goals and means for the creation of new forms of city life, more humane urban environments will emerge. Our urban world is now so much a "system" that it could be managed by democratic planning if we wished to turn

our private complaints outward into political channels. The first step in turning outward is to understand the system we confront.

The interactions between the national economy and the urban business institutions largely determine the nature of both workplaces and residences. The detailed analysis and reordering of these interactions is an enormously complex subject requiring great expertise, but in general outline—in the broad terms in which goals and policy must be debated it can be made clear enough for anyone who wishes to study and understand it. Moreover, a historical review is one of the best ways to begin. The different modes of business and the varying forms of cities that have existed in the past reveal the elements of our urban system like a skeleton.

To understand why American cities are as they are, we must learn to look for two sorts of activities. First, we must seek repeated relationships in the fragments of our everyday experience. Ours is a highly structured society and these repetitions are its framework. Second, we must peer out from the city itself watch the license plates on the trucks moving along the freeway, if you will—to recognize the city as a part of a national economy. The repeated interactions between the national economy and the local business organizations create the jobs and fund the housing of the city.

First, structure. Our urban history is the history of the conflicts and possibilities wrought by the growth of the nation and the growth of the units of its organization. It is also a history of the increasing interconnectedness of these units, which stems from the development of the economy and its cities. The organization of these connections into repeated interactions is the structure of the economy and the structure of its cities. For example, one can speak of the structure of a city in terms of its land-use patterns or of its transportation networks, for both of these produce regular, repeated connections in an ordered way. In this brief history the general categories of urban structure will be two: the national network of cities and the patterns of land use within the cities themselves. The category of economic structure will be the urban business institutions—the proprietors, partnerships, and corporations.

The general trend of the past hundred and fifty years has been toward an expansion of the national urban network, both as a whole and in its parts. The number of cities in the nation has multiplied, almost all cities became larger, and the interaction among them has steadily increased. In a parallel fashion the size of business units and the inter-

actions among them increased; small shops became giant factories, partnerships grew to corporations and then to conglomerate corporations of corporations, while the volume of business transactions, bank loans, sales, and shipments proliferated. Finally, the size of the units of land use in cities and the interactions among them increased. Mixed blocks of shops and houses gave way to specialized districts, business or residential, and whole suburbs and satellites of one class or one group of businesses emerged. Simultaneously the number of trips, messages, and exchanges within and among these enlarged areas rose in volume.

Our urban history, however, is not a simple tale of expansion. The general trend toward greater size and greater interconnectedness always contained the opposing characteristics of centralization and decentralization. Centralization looked toward the efficiencies to be realized from such expediencies as the gathering of all the steel producers into one city, such as Pittsburgh, or the unifying of many steel firms into one corporation, such as United States Steel. Decentralization looked toward the advantages of specialization obtainable from such practices as the locating of steel mills near different cities, as at Buffalo, Chicago, or Detroit, or the multiplication of the number of steel companies by having some specialize in bridges, some in rails, others in wire or structural members. In various periods of our history entirely different combinations of cities, businesses, and urban land use have appeared in response to the advantages of centralization and decentralization. In our own time we have highly centralized business organizations, highly decentralized business activities, and highly decentralized cities, and thus enjoy a wider range of possibilities for organizing both urban and economic structure than ever before.

To comprehend the boundaries of our current freedom we must look to the historical interactions among the national economy, business organization, local jobs, and local housing. The urban system that governs this set of relationships revolves around the interactions among the national economy, urban markets, and business organization.[1] For

[1] . I have taken this hypothesis of the relationship between city size, functional specialization, and the role of a city in the national network of cities from the modern empirical investigations of Beverly Duncan and Stanley Lieberson, Metropolis and Region in Transition , Beverly Hills, 1970, pp. 29-116; and Otis D. Duncan et al., Metropolis and Region , Baltimore, 1960, pp. 209-11, 248-75. I am also indebted to the more theoretical work of Eric E. Lampard, "The Evolving System of Cities in the United States: Urbanization and Economic Development," in Harvey S. Perloff and Lowdon Wingo, Jr., eds., Issues in Urban Economics , Baltimore, 1968, pp. 81-139; and Wilbur R. Thompson, A Preface to Urban Economics , Baltimore, 1965, pp. 37-60. The use of the hypothesis for the 1820-70 period finds support in the New York data of Allan R. Pred, The Spatial Dynamics of U.S. Urban-Industrial Growth, 1800-1914 , Cambridge, 1966, pp. 163-85; Robert Ernst, Immigrant Life in New York City , New York, 1949; and Robert G. Albion, The Rise of New York Port: 1815-1860 , New York, 1939.

example, a change from small firms to large corporations affects the urban markets used by them. A few corporations may encompass the trade formerly handled by hundreds of independent salesmen or dozens of small firms. At the same time, the financial and sales power of the corporations may make it possible for them to sell bread or beer over whole regions like the Midwest or even throughout the entire nation. Similarly, the concentration of a specialty in a single city (like flour milling in Minneapolis) draws related firms to that city, creating a local enclave for wheat and flour, with attendant shipping offices, railroad yards, bag companies, and the like. If the specialty of the city is far-reaching, as is the case in flour milling, local business will be reorganized to reflect the national scale, and a few big companies will dominate the local urban economic life. Finally, changes in the national economy, signaled by a transportation change like a new railroad or natural-gas pipeline or by a new banking system such as that brought into being by the National Banking Act of 1864, may restructure both urban markets and business organization by favoring some cities over others, by aiding some firms in their search for capital or their reach for sales to the disadvantage of others. Out of these countless interactions came the jobs of the nation's cities, and the differential rates of growth of individual cities and their jobs governed the local markets for housing.

Long ago the circle of national economic conditions, urban markets, and business organizations was remarkably stable, changing only slowly over time. Consequently, prior to the nineteenth century the multiplication of cities and their growth was a comparatively slow process. But beginning in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries a rapid and accelerating succession of changes in transportation and technology disrupted the stability of the past and brought about several almost total reorganizations within the urban system. New national economies, new markets, new businesses, new cities, and new urban structures have been spawned from these innovations. The angry citizens who today demand, for reasons of ecology or peace, that they be given control over science, space exploration, supersonic transport, or automobile emissions are attacking the vital sources of change in our society.

Transportation and technological change have influenced the urban system principally by creating opportunities for specialization and diversification. A new digger enables some farmer to specialize in the raising of potatoes, and a new road can also enable him to specialize by opening his farm to a wider market. In the same way a stitching machine for shoes, accompanied by good freight service to distant cities, may make a giant shoe factory thrive where none could have survived before. The same spectrum of changes in technology and transportation supports diversification of a city's economic activities, for if a city can reach new suppliers and new customers its merchants will be able to handle a greater variety of goods as well as a larger volume of them. The introduction of Rural Free Delivery postal service led directly to the rise of the great Chicago mail-order houses of Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward—an outstanding example of a simple link between transportation and diversification. The introduction of the stationary steam engine in the 1850s made it possible for cities that had been commercially oriented to branch out into mechanized production and thus to compete along certain lines with older waterpower mill towns.

To trace the patterns made by the impact of transportation and of technological innovation upon the system of American cities, it is convenient to divide our modern history into three periods, 1820-70, 1870-1920, 1920-, and then to describe the special characteristics of each period.[2] In each we shall examine the state of technology and transportation, because it is from a particular technological climate and a particular configuration of transportation that the form of our cities and our business institutions inevitably takes shape. From these two determinants flow the national network of cities, the condition of the urban markets, and the kind of business structure that flourishes. Finally, we shall look at the end products of the entire system—the jobs and the residential structure within the cities.

The decades from 1820 to 1870 were the years of the perfection of hand tools and horse-powered machines, the use of waterpower and steam engines, and the invention of myriad tools to perform tasks

[2] . This periodization is copied from the one used so successfully by Lewis Mumford in his The Culture of Cities , New York, 1938, pp. 495-96. In this work and its predecessor, Technics and Civilization , New York, 1934, Mumford elaborated a scheme first proposed by the Scottish biologist Patrick Geddes, Cities in Evolution , London, 1915. The geographer John R. Borchert has proposed a similar ordering of American urban history in his summary article, "American Metropolitan Evolution," Geographical Review , 57 (July 1967), 301-32.

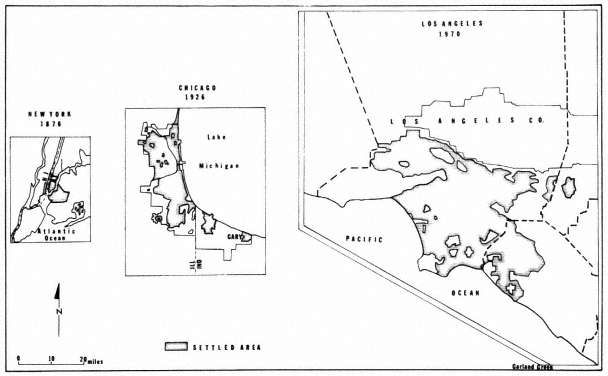

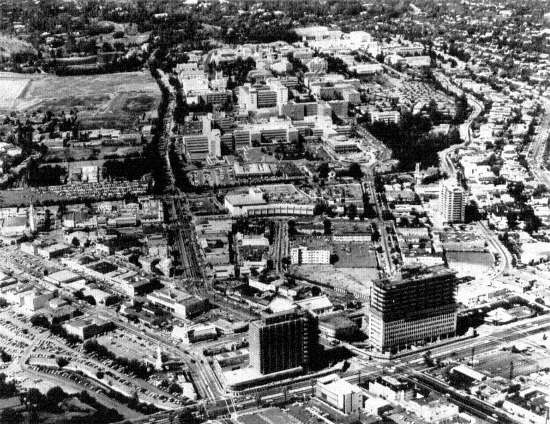

Figure III.

Expanding Size of the American Metropolis

SOURCE: O. W. Gray and Sons, The National Atlas, Philadelphia,

1876; Homer Hoyt, One Hundred Years of Land Values in Chicago,

Chicago, 1933; and U.S. Geological Survey maps.

formerly dependent on hand skills. But for all the new machinery, there was little mechanized production except in textiles and in some lines of ironworking. Most important, these were the years of the building of two new transportation networks, the water system of canals and steamboats, and the overland rail system. The new transportation gave rise to the big regional city and to the consequent organization of the economy around regional marketing and financial centers. Within business offices proprietorship and partnership prevailed, and in many cases the artisan competed with the sweatshop factory. Only a primitive specialization in respect to urban land existed, and the neighborhoods and districts of the big cities were highly mixed in their activities, ethnicity, and class.

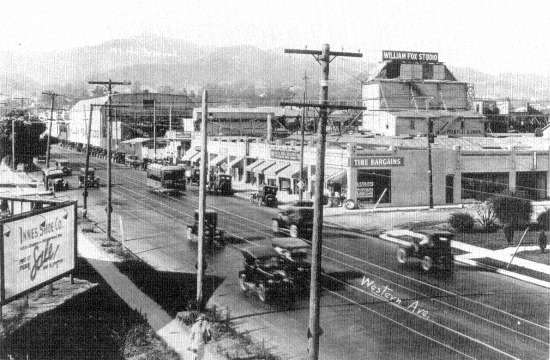

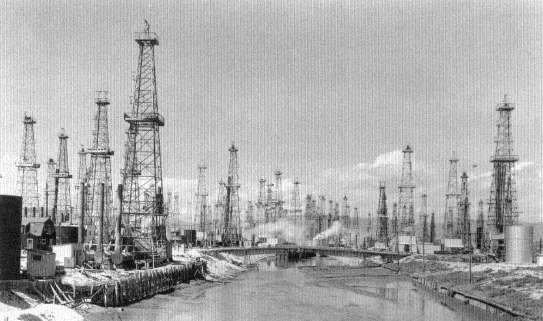

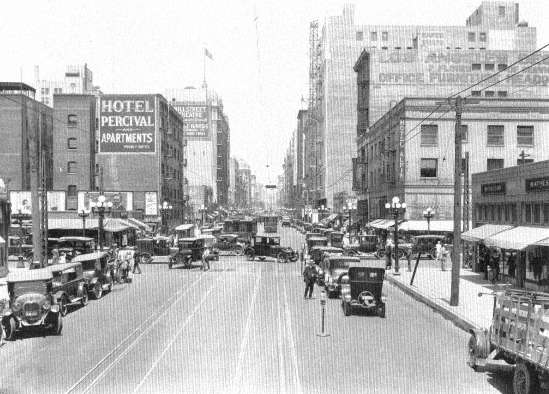

In the second period, from 1870 to 1920, science and engineering reached a sufficient degree of inclusiveness to be systematically applied to all aspects of manufacture. Fully mechanized in-line factory production became the hallmark of the era. Electricity, the new energy source, replaced waterpower and surpassed steam in the flexibility of its use. The national rail network reached its ultimate limit and was supplemented locally by the electric street railway, the motor truck, and the automobile. These were the modes of production and transportation that created the giant industrial metropolis and the related multicity manufacturing belts of the Northeast and Midwest. These sprawling urban regions, organized about New York and Chicago, both produced for and marketed for the nation. Within the cities themselves everything tended toward giantism. The corporation controlled American economic life. Armies of workers, gathered into factories, attempted to unionize so that they might redress the balance of power between labor and corporate management. Urban land, responding to the pressures of intense economic organization, itself became highly specialized. The central hive of the downtown district, with its department stores, office skyscrapers, hotels, railroad stations, loft manufacturing, and warehouses, was the most dramatic outcropping of specialized land use. Other uniformities also emerged. The industrial sector and satellite, the strips that sheltered the factories and suburban mill clusters, radiated from the central city. Simultaneously, the daily movement of passengers by the electric street railway encouraged commuters to cluster by class, ethnicity, and race. Colossal scale, centralization, and segregation were the telling signs of the industrial metropolis.

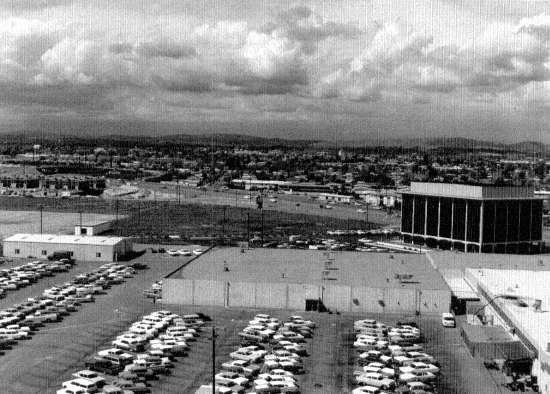

In our own time, that is in the years since 1920, more far-reaching science and more sophisticated technology have multiplied products for

common consumption and raised standards of living so much that more and more of the economy has turned away from farming, mining, and manufacturing into the provision of services, the seeking of international business, and the prosecution of foreign wars. New modes of transportation by express highway, airplane, and pipeline have made possible a rapid multidirectional movement of goods and people in tremendous volume. Production has accordingly been freed from a limited number of products and single locations to attune itself more finely to its markets. In the contemporary adaptation, business both builds multiple plants to capitalize on particular regional opportunities and expands the range of its products to meet specific demands of various kinds of customers. Atomic power has arrived to supplement the conventional generation of electricity, and the terror implicit in its military uses has provided an important rationalization for the undertaking of the disgraceful task of world domination.

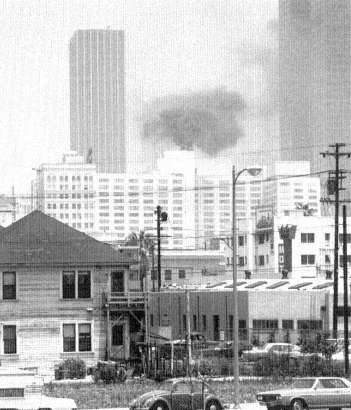

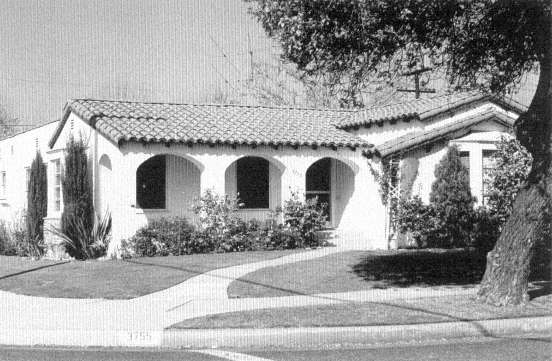

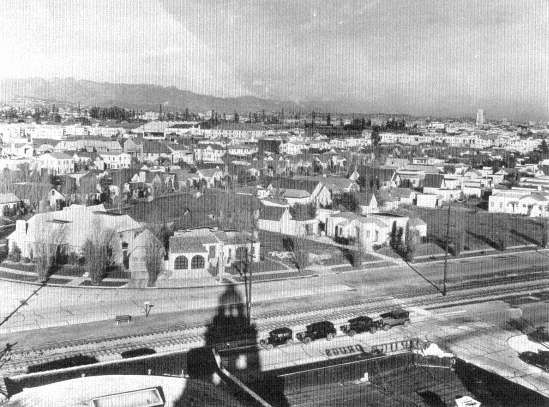

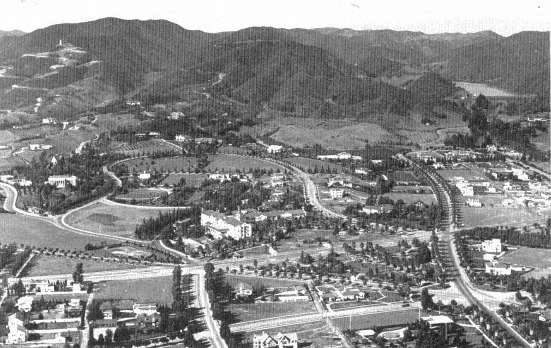

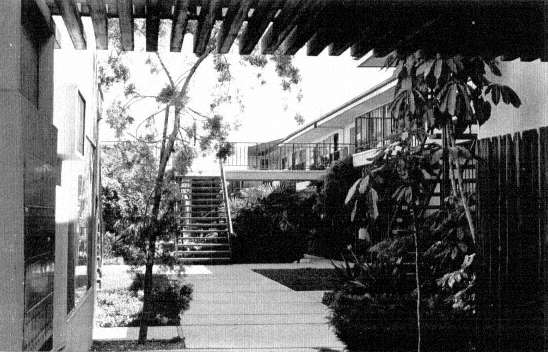

The new high-production, high-service economy gave rise to a characteristic urban structure—the megalopolis. Three megalopolises are so far identifiable, the Northeastern, Midwestern, and Californian. These are multicity, multicentered urban regions, distinguished from the former manufacturing belts by the huge volume of exchange within them, the almost continuous low-density settlement, and the sharing of business activities among the many urban nuclei. Here layers upon layers of economic specialties facilitate the production and marketing of highly complicated products and services. Within the megalopolises, as within the nation as a whole, private and public corporate enterprise has continued to elaborate. The corporation's concentration of political and economic power, with its use of telephonic communication, cost accounting, and computers, makes for giant scale and extreme centralization. The corporation's multiple activities, its search for good marketing locations, and its allocation of responsibility to branches and divisions, however, exhibit a tendency to decentralization that resembles the proliferation of centers, government agencies, and branches in the megalopolis itself. These contradictory impulses toward centralization and decentralization suggest a potential for flexible economic planning that can satisfy many publics and diverse demands. At the same time, the vast increase in bureaucratic work in both private and public corporations has moved the white-collar worker, his employers, and his suburbs into the forefront of urban development

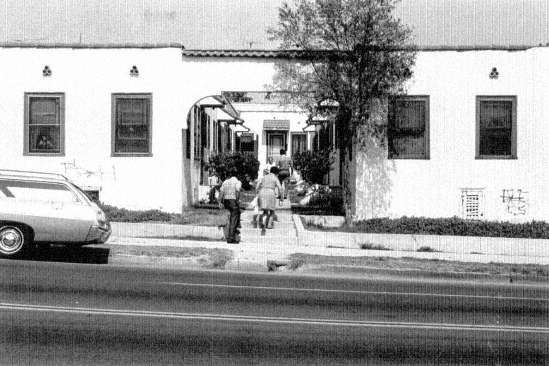

In land use, the clusters of the megalopolis have become more and

more specialized and segregated. Shopping strips, one-class suburbs, black ghettos, and industrial parks dot the urbanized region. Even the old industrial metropolis's downtown, so formidable a monument fifty years ago, has turned into an office and financial center, while its retailing, wholesaling, and manufacturing have been scattered all over the megalopolis. Residentially, various kinds of segregation have replaced the single-centered geographical organization of races and classes of the former era. Like the opposing tendencies within the corporation, the intensity of the social forces of specialization and segregation are countered by the vast extent of the megalopolis. The conflicts between prejudice and parochialism on the one hand and between low density and large open areas for rebuilding on the other suggest tensions that could offer a much broader range of urban choices than ever before.

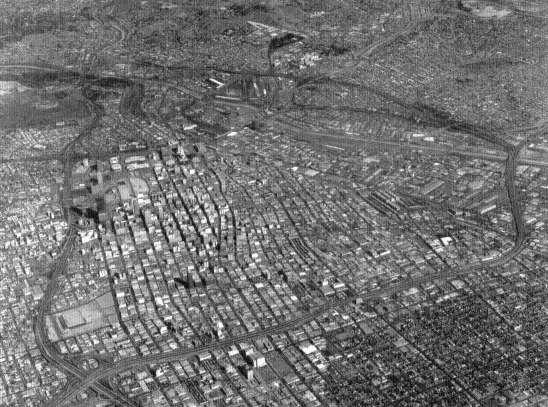

To serve as examples of each period, we will focus on typical large cities in each era; New York 1820-70; Pittsburgh and Chicago 1870-1920; and Los Angeles 1920-. Although each one will be dealt with as an archetype of its day, it should be realized that, despite remains of old neighborhoods and the persistence of past business specialties and urban styles, the power of the urban system is such that today metropolitan New York and Chicago resemble Los Angeles more than their former selves. Small cities could have served as well to reveal the skeleton of our urban system, but since we are now a nation in a state of panic over the conditions within our large cities it seemed most useful to concentrate on metropolitan history. Finally, since the history of the American urban system is a long one, it will be divided into three parts: first, the rest of this chapter, on the era of the big city; second, a chapter on the industrial metropolis; and third, a chapter on the megalopolis and the boundaries and potentialities of our urban world.

The Big City: 1820-70

No period of our history has surpassed the first half century of industrialization in its rate of change. Never again did the rate of urbanization climb so sharply. Not only did Americans conquer and settle the continent in these five decades, but their way of living on the land underwent a complete metamorphosis in which a national system of cities mobilized scattered villages and farms into a network of regional commercial and manufacturing centers. This sudden reorganization of American life, the forcing of a rural society into an urban mold, exacted a terrible toll

in everyday life. Nineteenth-century urbanization and industrialization inflicted punishment and suffering on city dwellers and tore at the fabric of society in the same ways that today's neglected cities do. Never were conditions more exploitative and dangerous to human life, but they were experienced in such a scattering of small factories, stores, and houses that no sustained labor movement could be organized to cope effectively with the new discipline. Yet cities of every size boomed with the possibilities that flowed from new resources, new methods of transportation, new ways of doing business, and new ways of making things.

Technological innovations, simple machines and inventions, were directed toward the products most basic to an agricultural society. The essence of industrial design in these years lay in perfecting simple, cheap products that could be sold in quantity to farmers: clocks, food mills, stoves, oil lamps, wagons, buggies, sewing machines, and the like. Such was the proliferation of devices and techniques turned out by trained engineers and scientists, as well as by gifted mechanics and tinkerers, that the foundations for the fully mechanized economy of the future were securely laid down.[3]

Inventions of the first era, then, attacked the basic concerns of food, clothing, housing, and transportation. In agriculture, tools like axes, scythes, and shovels reached a high level of perfection, taking on the enduring forms in which we use them today.[4] Similarly our alarm clocks, as well as the coffee mill and food grinder, eggbeater, metal spoon, and ice-cream freezer of our own kitchens, replicate designs of these inventive years. By harnessing horsepower to farm tasks formerly executed by hand, a great breakthrough was achieved in extending the scope of agriculture. Plows, mowing machines, hay rakes, reapers, and threshers broke the confines of the past which had tied armies of farm workers to the seasonal preparation of the land and to the harvesting of staple crops. Continuous, almost automated flour milling and an assembly-line process of butchering and meat packing slashed labor costs and permitted the large-scale production of these key farm items. The formerly ubiquitous icebox was also an invention of these years, and at the same time the technique of cooling chests and whole rooms by ice

[3] . This description of the process of early technological change rests on a brilliant article of Dorothy S. Brady, "Relative Prices in the Nineteenth Century," Journal of Economic History , 26 (June 1964), 145-203.

[4] . Sigfried Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command , New York, 1948, pp. 141-49.

was mastered.[5] Methods providing for the safe canning of meats, fruits, and vegetables were introduced. By 1870 the United States possessed the basic components for a range of modern food products. Farm and city dwellers were alike freed from the limitations imposed by the short list of cheap all-year staples formerly available to them; to cornmeal, wheat flour, salt fish and salt meat, dried fruit and vegetables, and whiskey and beer were now added much more than merely local and seasonal supplements. One historian has underlined the change by noting that toward the end of this era the workingman could expect to find on his table such delicacies as fresh fish chowder and apple pie with some regularity.[6]

The textile and clothing industries were revolutionized by the importation of British techniques and by further advances in American inventions, and the cost of these necessities was drastically cut for farmer and city dweller alike. During the first decades of the nineteenth century, fully integrated cotton mills, performing every operation from spinning and weaving to finishing and printing, came into production in New England and elsewhere in the Northeast. They were soon followed by woolen mills and by a parallel improvement in water turbines to drive the mills.[7] In the same years the manufacturers of rifles—the most expensive tools purchased by the early nineteenth-century farmer—perfected what was then termed the "American system" of using interchangeable parts. In time the same methods enabled the machine shops of the East to invent and build milling machines and other metalworking tools which could turn out boxes of identical parts. Accordingly, when the practicable sewing machine was invented in 1846 these new techniques were at hand for its mass production and for its distribution for home and factory use. By the time the Civil War broke out, cloth and clothing were thoroughly modern machine-made products.[8]

In construction, a succession of inventions for the manufacture of hardware, windows, doors, stair parts, flooring, and uniformly sized

[5] . Oscar E. Anderson, Jr., Refrigeration in America , Princeton, 1953, pp. 14-70.

[6] . Brady, "Relative Prices," 192.

[7] . Robert B. Zevin, "The Growth of Cotton Textile Production after 1815," and Peter Temin, "Steam and Waterpower in the Early Nineteenth Century," in Robert W. Fogel and Stanley L. Engerman, The Reinterpretation of American Economic History , New York, 1971, pp. 122-47, 228-37.

[8] . Carroll W. Pursell, Jr., "Machines and Machine Tools, 1830-1880," in Melvin Kranzberg and Carroll W. Pursell, Jr., Technology in Western Civilization , I, New York, 1967, pp. 392-405.

lumber united with the balloon-frame pattern of nailed beams and boards to cut the costs of building.[9]

The inventions that appeared between 1820 and 1870 saved an incalculable number of man-hours, skilled and unskilled, but by today's standards the cumbersome use of the tools still required a great deal of supporting labor. A farmer had to drive the team that pulled the new reaper; each machine tool needed an operator to feed and guide it; textile mills still depended on armies of women and children to tend the looms and spinning frames. Customarily the machine at this time performed only a single step in the total process; it stitched the seam but not the buttonholes, it sewed the soles but could not form the last, it cut door parts that had to be glued, assembled, and sanded by man. Flour milling was almost fully automated, but the frequently cited meat-packing assembly line was nothing more than a way to move the work past a row of skilled men. The partial introduction of machines and the partial redesign of products, together with the small and often seasonal scale of many markets, meant that in every shop from iron foundries to shoe factories there was a considerable volume of discontinuous handwork. There was much carrying of things from one machine to the next, of setting them up for one batch and then turning to the next, and short runs of products went back and forth from machine to hand to machine.

Innovations in transport resulted in the creation of two new networks that gave the inventions a revolutionary impact, and the networks had the effect of making each invention reverberate throughout the urban system. All the elements of the urban system were themselves transformed by the new transportation, and the changes were felt in urban markets, the structure of business, and the national economy. It was transportation that made the building of a national network of cities possible even while it revolutionized the social conditions within them by vastly enlarging the economic opportunities for thousands of small businessmen.

America built its canal system in two spurts, from 1815 to 1834 and from 1836 to 1854. In the first period more than two thousand miles of canals were built to connect the Atlantic port cities with each other and with the cities and towns of what was then the West. The river steam-

[9] . Dorothy S. Brady, "The Effect of Mechanization on Product Design in the Course of Industrial Development," Third International Conference of Economic History , Munich, 1965, pp. 7-15.

boat and the canal were complementary; the steamboat made upstream travel swift and reliable, cutting the time of the journey from weeks to days and hours, and canals flowed through land formerly accessible only by difficult overland pathways. By substituting an easygoing hitch of one to three horses or mules for the straining teams of the past, freight costs were cut by 90 percent. On the Erie Canal in New York, the most successful of them all, average rates for a ton-mile of goods moving from Buffalo to New York City fell from nineteen cents in 1817 to two cents and finally to one cent after some years of operation.[10]

As the second canal boom went forward, extending existing lines and adding new Western ones, the railroad and its companion the telegraph stepped up the possibilities for high-speed travel and communications. The first railroads of the 1830s radiated from the old port cities like Baltimore and Boston to garner nearby trade. In the 1840s small cities like Albany and Binghamton in New York State made local efforts of the same sort, and big cities turned to the financing and promotion of long Western rail lines that added all-weather intercity routes to the canal connections. The railroads, unlike the state-financed canal routes, were very much the products of the cities themselves. Whether one thinks of giant projects like the Eastern Division of the Union Pacific and the Pennsylvania Railroad or of little local runs like the Albany and West Stockbridge, we find behind them Kansas City, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and Albany as prime movers as well as beneficiaries.[11]

Compared to anything that had gone before, the railroad was a wonderfully versatile transportation invention. It could cheaply join a series of small coal valleys in Pennsylvania to a canal or a larger rail complex, or it could tie together the mill towns and cities of New England. It could as readily fan out over the prairies, as it did in Illinois, opening an entire state to market agriculture. In 1840 there were three thousand miles of rails and three thousand miles of canals; by 1854 one could travel by rail all the way from New York to Chicago and St. Louis. Fifteen years later the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific

[10] . Carter Goodrich, ed., Canals and American Economic Development , New York, 1961, pp. 172, 184-85, 227-29.

[11] . Harry H. Pierce, Railroads of New York, A Study of Government Aid 1826-1875 , Cambridge, 1953, pp. 115-16; Charles N. Glaab, Kansas City and the Railroads: Community Policy in the Growth of a Regional Metropolis , Madison, 1962, pp. 103-23.

joined to complete a transcontinental line; in a mere half century the country had undergone a thoroughgoing revolution in transportation.[12]

The powerful effect of emerging transportation upon society and its economy stemmed precisely from its ability to widen the market opportunities of everyone it served. By widening the market, that is by increasing the number of potential customers, specialization was always encouraged. Why specialization? Because in almost all cases profits may be augmented by a concentration on those crops which grow best on a given piece of land, on those products which can be made most cheaply, or on those goods most easily bought or handled in volume. For example, New York merchants trading in general metal products turned to the importation of copper or tin or railroad iron, or they became dealers in blacksmith supplies or in simple hardware for country stores.[13] The expanded grasp of the city in turn fostered rural specialization. Upstate farmers responded to the faster and cheaper transportation by switching from the few limited cash grain crops of the past to orchards, dairies, stock farms, and wool. In the process their prosperity swelled the market for manufactured goods and city services.[14]

By myriad interactions a process of development stimulated by transportation had begun. Ease of transport led to more specialized and more efficient methods of agriculture which in turn extended the markets for farm products, and the increased prosperity of the farmers gave rise to cities to supply them with a rapidly lengthening list of comforts and necessities, such as loans, hand tools, farm machinery, pots and pans, food mills, furniture, pumps, clothing, and so on and on. In this interaction lay the workings of the urban system, the truth behind the bombast of railroad Congressmen, state canal promoters, and town and city merchants, all of whom habitually hailed every road, canal, rail, or telegraph line as an "improvement."

Indeed, transportation did transform the national network of cities, changing it from a string of small commercial Atlantic coast cities into a

[12] . George R. Taylor, The Transportation Revolution, 1815-1860 , New York, 1951, pp. 32-103.

[13] . The interaction between firm specialization and sales area is neatly documented in Elva Tooker, Nathan Trotter, Philadelphia Merchant, 1787-1853 , Cambridge, 1955, pp. 108-31; for Trotter's competition, see Albion, The Rise of New York Port: 1815-1860 , pp. 248-49.

[14] . Clarence H. Danhof, Change in Agriculture: The Northern United States, 1820-1870 , Cambridge, 1969, pp. 4-23.

continental complex of trading centers to which were added a scattering of wholly new specialized manufacturing cities. In 1820 the nation possessed but five cities (New York, population of the present five boroughs 152,000; Philadelphia, 65,000; Baltimore, 63,000; Boston, 43,000; New Orleans, 27,000). Half a century later the leading commercial centers had grown into cities of more than a quarter of a million inhabitants. The placement of these cities reflected their functions as import-export centers joining Europe to the United States via the ocean and railroads, and as assemblers and distributors of goods through the continental United States (1870 population figures: New York, 1,478,000; Philadelphia, 674,000; St. Louis, 311,000; Chicago, 299,000; Baltimore, 267,000; Boston, 251,000). To support these six big cities, forty-five cities having populations ranging from twenty-five thousand to a quarter of a million had grown up along with them (Table 1 ).

The national network of six big cities and forty-five lesser ones reflected the extent of the organization of the national economy achieved

TABLE 1 | |||||||||||

Towns | Cities | Metropolises | Total Urban | ||||||||

% U.S. | % U.S. | % U.S. | % U.S. | ||||||||

No. | Pop. | No. | Pop. | No. | Pop. | No. | Pop. | ||||

1820 | 56 | 3.58 | 5 | 3.63 | - | - | 61 | 7.21 | |||

1870 | 612 | 9.86 | 45 | 6.74 | 6 | 8.21 | 663 | 24.81 | |||

1920 | 2,434 | 15.23 | 263 | 16.00 | 25 | 19.64 | 2,722 | 50.87 | |||

1970 | 5,520 | 28.34 | 859 | 24.03 | 56 | 20.75 | 6,435 | 73.12 | |||

Population by Size Groupings | Total Population | ||||||||||

Towns | Cities | Metropolises | Urban | U.S. | |||||||

1820 | 344,000 | 349,000 | - | 693,000 | 9,618,000 | ||||||

1870 | 3,933,000 | 2,689,000 | 3,280,000 | 9,902,000 | 39,905,000 | ||||||

1920 | 16,218,000 | 17,030,000 | 20,910,000 | 54,158,000 | 106,466,000 | ||||||

1970 | 57,577,000 | 48,829,000 | 42,151,000 | 148,557,000 | 203,166,000 | ||||||

Note : All cities are assigned population according to their changing political boundaries except New York, which is listed as one city of five boroughs in all periods. The Towns category in 1970 includes unincorporated urban fringe areas of 2,500 or greater numbers of inhabitants. Calculations were made from US. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1957 , Washington, 1960, p. 14; Fourteenth Census of the U.S. 1920 , 1, Population , Washington, 1921, pp. 62-75; Statistical Abstract of the U.S.: 1971 , Washington, 1971, p. 17. Some disagreement in detail exists among these sources, and in such cases the Fourteenth Census has been followed because it gave specific listings of city populations by name of city. | |||||||||||

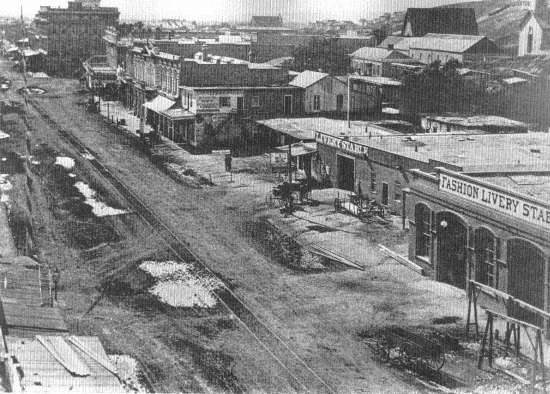

during the years 1820-70.[15] All fifty-one cities constituted an integrated commercial interdependency, a hierarchy of trade governed by New York and supervised by the regional centers of Philadelphia, St. Louis, Chicago, Baltimore, and Boston. Banking and wholesale trade in farm staples and some manufactured goods were controlled by the market rates and prices in these national and international trading centers.[16] Wheat, cotton, corn, banknotes, bonds, cloth, iron, books, and all manner of goods for which there were large markets were traded in the regional centers, but with an eye to New York and ultimately to Atlantic demand and prices. Regional bankers and merchant houses maintained correspondents and agents in New York to keep them posted and to negotiate for purchases and sales. In view of these financial and commercial linkages, the United States in 1870 could be said to be an integrated national economy organized around its major city markets.

The entire economy, however, was as yet only partially organized on a national basis because manufacturing had not yet settled into the pattern whereby each specialty located in its best site, and from such a single base or cluster of bases sold its products throughout the nation. In 1870 such common items as stoves, hardware, kitchenwares, farm machinery, steam engines and locomotives, carriages, wagons, clothing, and shoes were being manufactured in cities and towns all over the United States. The network of cities reflected this fragmented and overlapping placement. The six largest of them had added a wide range of manufactures to their commercial base and were producing an extraordinary variety of goods from fur muffs and gas lights to ships and steam engines. In the duplication of effort, Philadelphia's furniture mills made the same Windsor chairs as their Boston, New York, and Chicago counterparts, while the Philadelphia weavers made a line of goods from mosquito netting to muslins, repeating the line of the textile towns in New York and New England. Such repetitiousness reflected the mixed

[15] . The forty-five cities in rank order were: Cincinnati, New Orleans, San Francisco, Buffalo, Washington, Newark, Louisville, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Jersey City, Detroit, Milwaukee, Albany, Providence, Rochester, Allegheny (now part of Pittsburgh), Richmond, New Haven, Charleston (South Carolina), Indianapolis, Troy, Syracuse, Worcester, Lowell, Memphis, Cambridge, Hartford, Scranton, Reading, Paterson, Kansas City (Missouri), Mobile, Toledo, Portland (Maine), Columbus (Ohio), Wilmington (Delaware), Dayton, Lawrence, Utica, Charles-town (Massachusetts), Savannah, Lynn, Fall River, Springfield (Massachusetts), and Nashville. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Fourteenth Census of the U.S.: 1920, Population , Washington, 1921, p. 81.

[16] . Duncan and Lieberson, Metropolis and Region in Transition , pp. 43-58, 116.

tendencies of the times, for each big city was in part a market unto itself and produced for its own region, even while it was also a dealer in outside goods now beginning to be produced for national markets. It took perfection of the rail network and the organization of the large corporation to put an end to these anomalies.

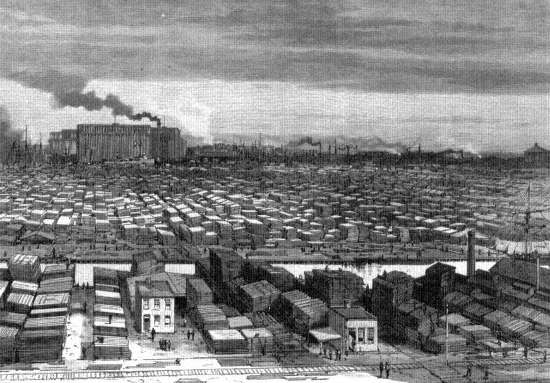

The lesser cities reflected the same lack of national specialization in manufacturing. In the list of forty-five stood commercial cities whose principal activity lay in trading with their rural hinterlands, as had Baltimore and Boston in previous years. Such cities as New Orleans, Memphis, Indianapolis, Kansas City, Portland (Maine), and Rochester served their local regions with imported goods and traded as well in the local specialties of sugar, cotton, corn, cattle, grain, and lumber in the traditional manner of commercial cities. Their rapid growth over a half century reflected the settlement of the continent and the impact of river, canal, and rail transportation on growth and diversification. Other cities on the list represented the new industrial specializations for large-scale production: Lowell, textiles; Reading and Scranton, anthracite; Providence, machine tools; Hartford, guns; Utica and Troy, textiles and machinery. In some cases an industrial specialty contributed to a commercial city's growth, as did ironworking in Pittsburgh, meat packing in Cincinnati and Chicago, and oil refining in Cleveland. To appreciate fully the contribution of early manufacturing to the urbanization of the United States, one has only to consider the case of the still largely rural South, which had only eight cities on the national list of 1870. Although scholars disagree concerning the reasons for the retarded urbanization and industrialization in the region south of the Ohio and east of the Mississippi River, its agricultural economy in 1870 resembled an underdeveloped eighteenth-century colony and had little in common with the boom conditions of the Northeast and Midwest.[17] One can perceive the lineaments of the future growth of the two great manufacturing belts in the 1870 mixture of cities, factory towns, and commercial centers which had already grown up there.

Just as the national network of cities had transformed the lives of American farmers, so the sheer magnitude of these new cities radically affected the lives of city dwellers. The metropolises were after all five to ten times as large as the leading cities of half a century before, and it is not an exaggeration to maintain that in the years from 1820 to 1870 no

[17] . Douglass C. North, The Economic Growth of the United States, 1790-1860 , Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1961, pp. 4-7, 189-203.

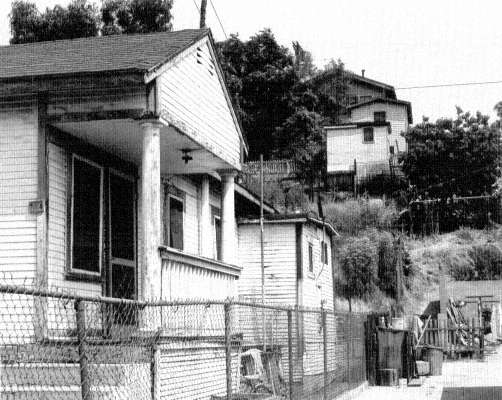

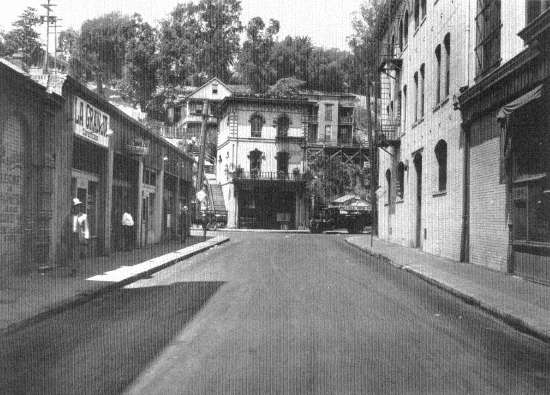

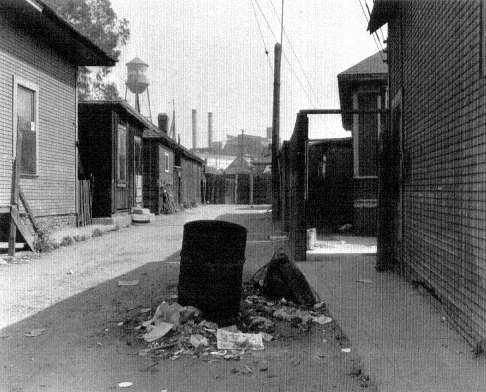

important facet of urban life was left untouched by the rapid change in scale. Yet the setting for these changes would now appear strange to us because the cities of the 1820-70 era were so different from our own. They were cities of storekeepers and small sweatshop factories, of businesses run by one boss or a few partners, of the scattering of shops and workrooms among residences, of mixed neighborhoods of rich and poor, native and immigrant, and of strong smells and slovenly habits coexisting with stiff and polished propriety.

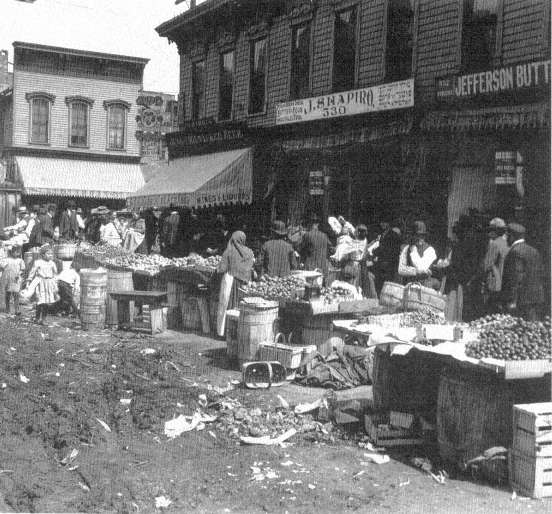

The enlarged markets for the sale of goods within the cities worked in two ways to change the organization of business and the nature of urban jobs. First, as the city grew so did its needs, and residentiary industries such as little local bakeries spread through the neighborhoods of the city.[18] Second, export industries were bound to multiply and expand when a city could sell to a broader region around it. For example, New York's cracker industry grew lustily to sell barrels of hard crackers far and wide to country stores and to ships' captains. In many cases local and distant markets overlapped. New York sold steam engines to shipbuilders and factories in the immediate environs even as it exported them to distant mills; it made the same line of clothing for local workingmen that it made for country stores or Southern plantations.

The new markets relentlessly favored a different kind of businessman, called in those years a contractor or capitalist, whom today we could perhaps best describe as a hustler. Inventions were important in the reorganization of business by small proprietors and partnerships, but since early machinery served at most as a substitute for a few hand tasks, the principal gains in production accrued to bosses who could organize their shopworkers for a steady production of uniform output. These emerging businessmen recruited labor from the old independent artisan shops where a complete product had been made by one man, or by a couple of men assisted by a boy or a family. They moved artisans, unskilled immigrants, women, and children into their own shops, where they could watch over them. Or they carried unfinished garments and products from shop to shop and tenement to tenement, issuing the strictest instructions for their completion. Instead of waiting for orders from individual customers to come in the door, these capitalists solicited

[18] . Sam Bass Warner, Jr., "The Feeding of Large Cities in the United States, 1860-1960," Third International Conference of Economic History , Munich, 1965, pp. 83-87.

business from wholesale merchants and produced for the expanding anonymous urban market. By a combination of hard driving, strict supervision, and a certain amount of machinery, they transformed such cities as New York, Philadelphia, and Boston from artisan towns into hives of small factories and wholesale outlets (Table 2, page 93).

The transformation went forward even in the most ordinary and unmechanized activities. Often the old and the new existed side by side. In New York there was still work in 1870 for the carpenter who followed the ancient custom of bidding on a house or two each year and doing most of the work himself, for the tailor who measured and fitted each suit individually, or for the wood carver who carried his tools from shop to shop, following his own preferences in employers. But higher rewards than a commonplace living wage awaited the man who determined to expand. A carpenter could become an entrepreneur by transforming himself into a contractor and hiring a mixed crew of men—some skilled but many unskilled—to install the new factory-produced windows, doors, moldings, and stairs. By rushing from job to job he could manage to erect whole groups of houses by his own energy and by driving his workers, and so enjoy the patronage of speculators in the city's periodic real-estate booms. He could grow wealthy while his old crew of skilled artisans and day workers would be left behind. Similarly a tailor might break down the skills of his craft into its components of cutting, basting, buttonhole making, and the like and place his unskilled or semiskilled tasks in the homes of poor women, children, and immigrants. He could prosper in the urban market for workers' ready-made clothing and could sell as well to the country stores whose merchants came regularly to the big cities to buy stock.

Well before sewing machines were invented, before tin ceilings or cast-iron store fronts were used, even before balloon-frame house construction had been popularized, the merchant capitalist and contractor came forward in the American city to reorganize its labor. These were the drivers of men who lengthened the workers' hours, abolished the holidays and self-determined comings and goings of independent artisans, broke down the craft traditions, and oriented the business of the city toward ever spiraling production and sales.[19]

[19] . John R. Commons, et al., History of Labour in the United States . I, New York, 1918, pp. 338-50; for the garment manufacture case, Oscar Handlin, Boston's Immigrants: A Study in Acculturation , Cambridge, rev. ed., 1959, pp. 75-77; for building trades, Brady, "Effect of Mechanization on Project Design," p. 12.

The cities of course had their inventors too, men who saw opportunity in the expansion of the day and made their fortunes by adding personal mechanisms and techniques to existing methods. In New York City, Peter Cooper (1791-1883), former wood carver, manufacturer of shears for the napping of wool cloth, and grocer, made the decision to compete with imported glue and gelatin. By careful attention to the details of manufacture and with the aid of a few inventions bearing on the processes, he was able to offer a cheaper and more uniform product than had been in use before. As New York and its markets grew, his glue boiling prospered magnificently.[20] There were many inventor-manufacturers like Cooper in the big cities of this period, such as the shipbuilding Stevens family in Hoboken in the port of New York and the machine-making Sellers brothers in Philadelphia, but invention also flourished in mill towns over the whole East and Midwest. In this era of tinkering, wherever there were machines there were inventors.

The big cities, however, did tend to have a particularly encouraging effect on inventions and in time more or less concentrated the innovators within their bounds. This encouragement was compounded of the complementary suppliers and marketing firms that surrounded them in the urban districts. Cooper, for example, had set his glueworks near the slaughterhouse of Henry Astor, where hooves were abundant and cheap. In these days before dressed meat could be shipped in refrigerator cars and indeed before there were cattle cars on the railroads for the shipment of livestock, cattle were driven to the city to be killed, and New York City was the slaughtering capital of the nation. Furthermore, the city's users of glue—shoemakers, bookbinders, furniture manufacturers, and so on—were located near at hand as ready consumers of his product, and he was thus dealing with America's largest wholesale and retail market. Although the city of this period was made up of a multiplicity of small firms—smaller in most instances than Cooper's glueworks—the clustering of complementary businesses made expansion easy.

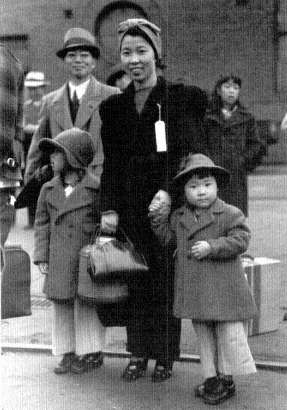

The swelling of urban markets into a partially integrated national economy and the consequent transformation of business into a swarm of small aggressive production and marketing firms had drastic and enduring consequences for urban workers. The explosive growth of cities created something like a labor vacuum into which were sucked thou-

[20] . Allan Nevins, Abram S. Hewitt, With Some Account of Peter Cooper , New York, 1935, pp. 45-62.

sands upon thousands of rural migrants. A profound cultural shock ensued. Native workers had to face up to the reality of competing and coexisting with waves of foreign immigrants. To add to the difficulty of their adjustment, depressions and periodic mass unemployment now threatened their jobs for the first time in our history. The closer linkages of urban work to national and international sales made each city economy a captive of worldwide business cycles. Finally, the new stricter discipline and the growing size of shops and factories reversed the egalitarian trends of the early merchant-artisan city and instituted the deep class cleavages between hand workers and paper workers, between working class and middle class.

The nineteenth-century American city was a magnet for immigrants. From the 1820s onward, young men flocked to the city from American farms and towns as well as from European villages, towns, and cities. In the years before 1870, Great Britain, Ireland, and Germany supplied most of the immigrants (Table 3, page 168). Over and over, the story was repeated of the eager youth who, in seeking his fortune, accepted the heightened pace of work and the endless hours of labor as a challenge. He tried to work ever harder than his competitors, contributing his youth to the energy of the city. A tale of that period that speaks of boys from the New England countryside makes clear the standards of morality and behavior by which such newcomers were judged:

With a few dollars and a mother's prayer, the young hero goes forth to seek his fortune in the great mart of commerce. He needs but a foothold. He asks no more, and he is as sure to keep it as the light will dispell darkness. He gets a place somewhere in a "store." It is all store to him. He hardly comprehends the difference between the business of the great South street house, that sends ships over the world, and the Bowery dry goods shop with three or four spruce clerks. He rather thinks the Bowery or Canal street store the biggest, as they make more show. But wherever this boy strikes, he fastens. He is honest, determined, and intelligent. From the word "go" he begins to learn, to compare, and no matter what the commercial business he is engaged in, he will not rest until he knows all about it, its details—in fact, as much as his principals.

Another characteristic of the future merchant is this—no sooner has he got a foothold, than the New England boy begins to look for standing room for others. Perhaps he is the son of a small farmer who has several other children. The pioneer boy, if true blue, does not rest until one by one he has procured situations for all of his brothers. If he has

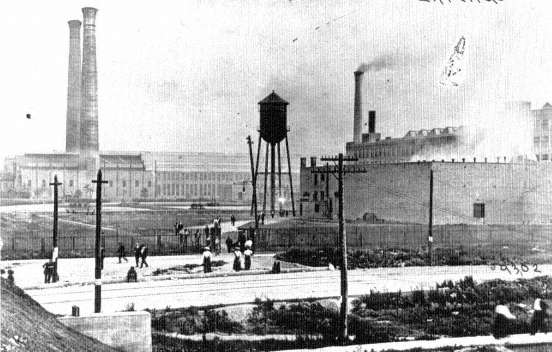

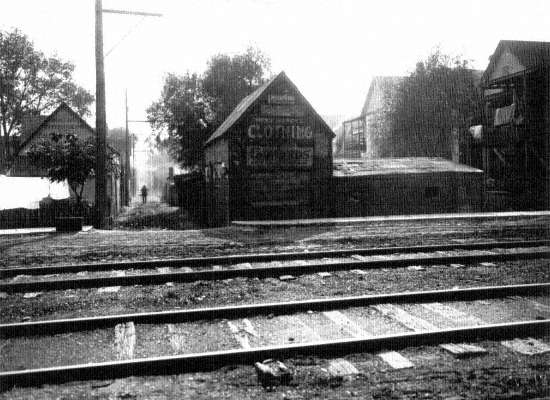

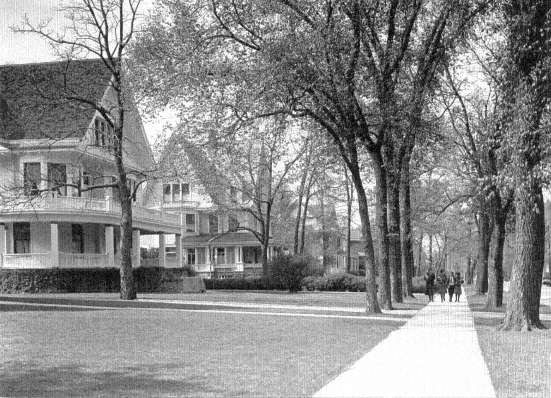

Illustrations

The Big City

Urbanscape

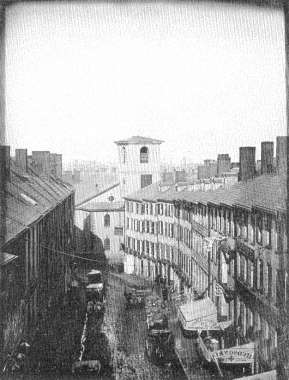

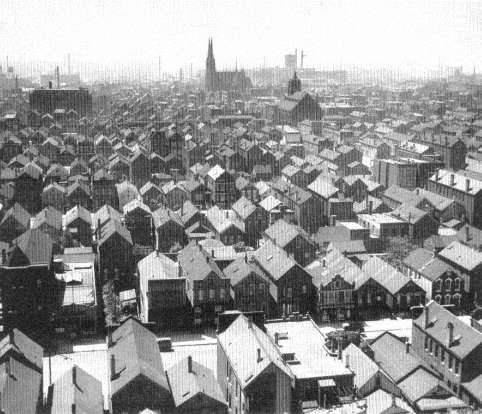

15. New York, 1849. Half a million people crammed into a jumble of small buildings, with single-family houses, boardinghouses, warehouses, factories, slaughterhouses, and churches—a typical early industrial hive. Eno Collection, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

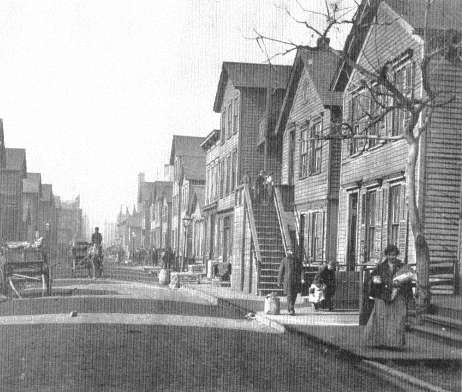

16. Boston, 1855. Four- and four-and-a-half-story shops and houses of the West End, masts of ships in the harbor behind Brattle Square church. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of I. N. Phelps Stokes, Edward S. Hawes, Alice Mary Hawes, Marion Augusta Hawes, 1937

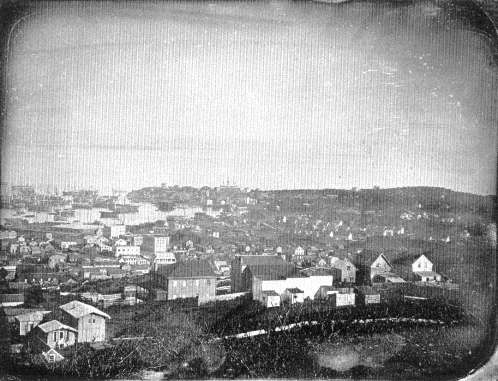

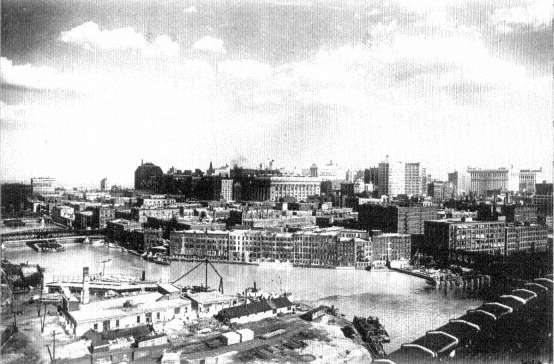

17. San Francisco, 1850-51. A regional trading city begins as a country town. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of I. N. Phelps Stokes, Edward S. Hawes, Alice Mary Hawes, Marion Augusta Hawes, 1937

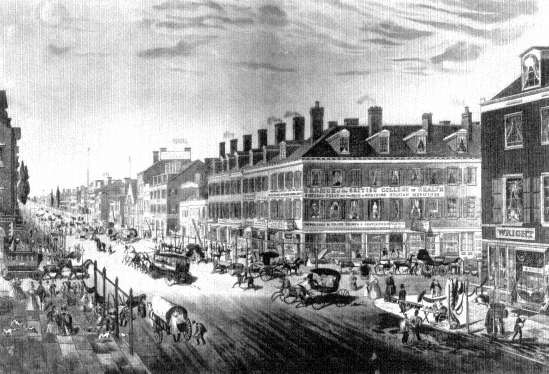

18. Broadway, New York, 1834. Unpaved street, with horse-drawn omnibusses, wagons, and carriages which passed busy sidewalks edged with storefronts, awning poles, and frames of streetside peddlers. Eno Collection, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

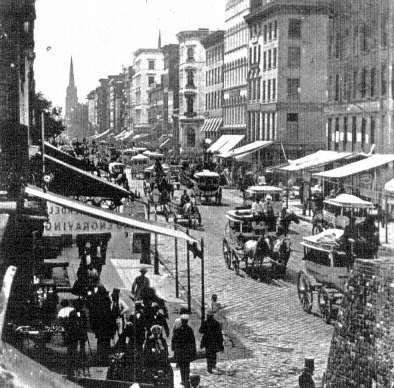

19. Broadway, New York, 1870s. Public amenities of cobblestone pavement and gas lights have been added, and buildings have grown to five and six stories since 1834, but the traditional urban framework of full sun-lit streets with horse-drawn traffic and busy pedestrian sidewalks still contain the intense clustering of commerce and manufactures. New-York Historical Society

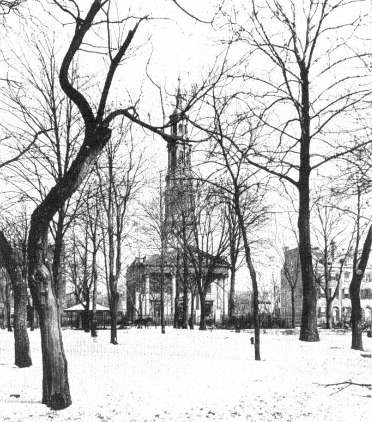

20. Hudson Square, New York, 1866-67. Relentless moneymaking left few open spaces in big cities of the early industrial era. Here, St. John's Church and houses for the wealthy of the Federal days provide a rare interval of urbane relief. New-York Historical Society

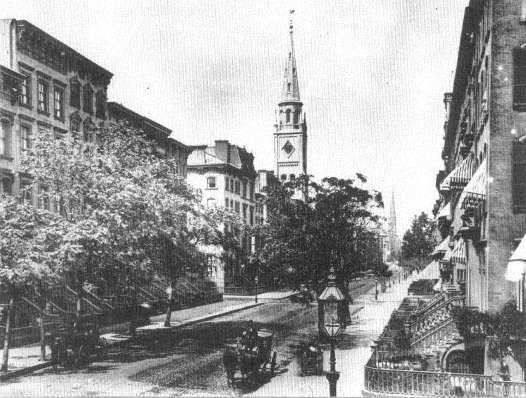

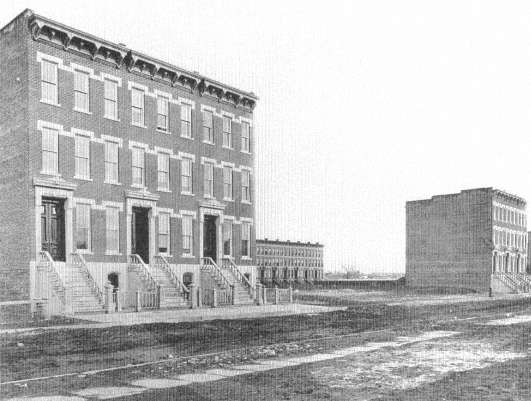

21. Fifth Avenue from 28th Street, New York, 1865. Ultimate amenities of big-city residential life: clean, paved streets and sidewalks, cabs at the curb, gas lights, cast-iron fences, basement kitchens, servants in the attic, modern plumbing, and an unbroken strip of brick and brownstone row house propriety, with a few young trees. New-York Historical Society

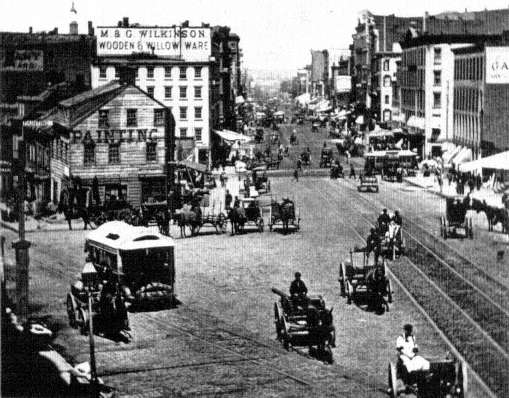

22. Working-Class New York, Canal and Mott Streets, ca. 1870. The workingman's big city, with factories, craftsmen's rooms, cheap retail stores, slum housing, in varied buildings—from old wooden houses and well-propor-

tioned Federal blocks to the new tall, narrow, heavy-corniced tenements of contemporary fashion. New-York Historical Society

23. West Washington Market, New York, 1880s. As the city's population grew, markets expanded from old neighborhood stalls, where housewives shopped daily, to specialized farmers' and grocers' wholesale distributing centers. Here, a market built in 1858. New-York Historical Society

24. West 133rd Street, New York, ca. 1877. Like today's suburban fringes, speculators' housing took up broken parcels of land at the city's growing outer edge. New-York Historical Society

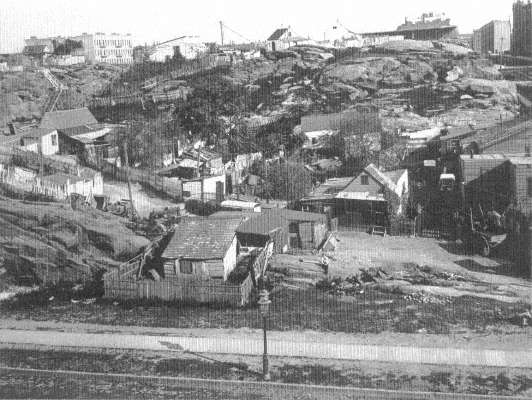

25. Fifth Avenue, 116th and 117th Streets, New York, 1893. The fringe shanties of the poor. New-York Historical Society

Business

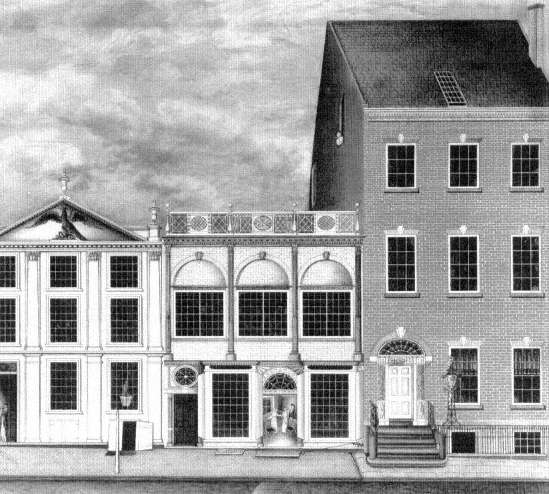

26. 168-172 Fulton Street, New York, ca. 1820. The shop and warehouse of the famous furniture maker Duncan Phyfe. Typical small-scale enterprise of the first era of industrialization. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1922

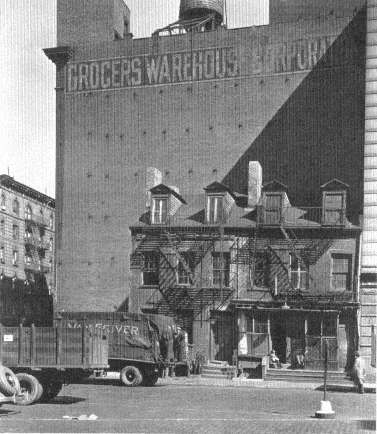

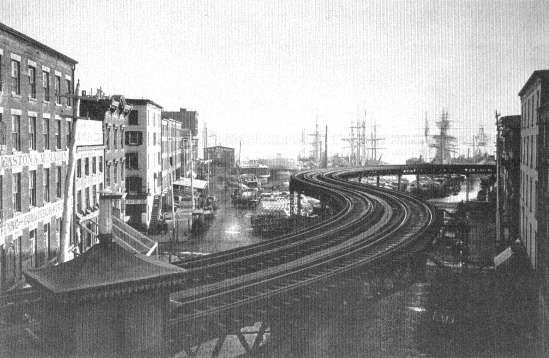

27. 512-514 Broome Street, New York, 1935. The photographer Berenice Abbott in her Changing New York recorded extremes of the big-city era; two old houses towered over by a six-story warehouse, the limit of construction before the steel-frame skyscraper of the industrial metropolis. Museum of the City of New York

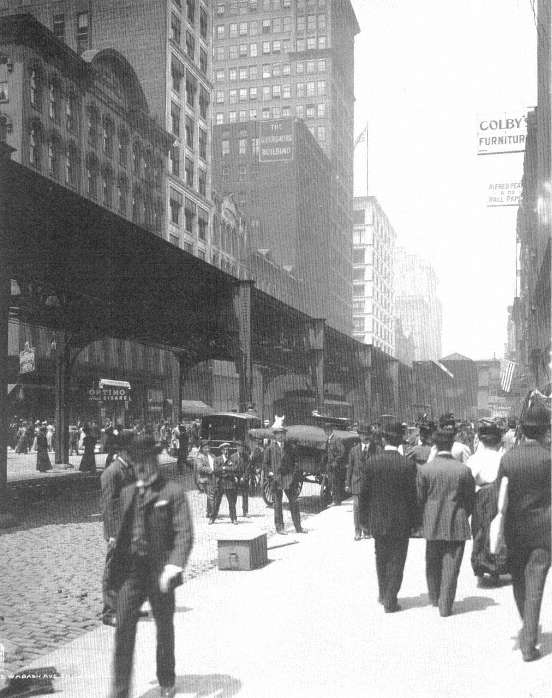

28. Coenties Slip, New York, ca. 1879. Three-to-four-story merchant warehouses and docks overshadowed by new elevated railway, whose high volume of traffic raised downtown land values until the traditional urban framework could no longer accommodate the enlarged scale of business enterprise. New-York Historical Society

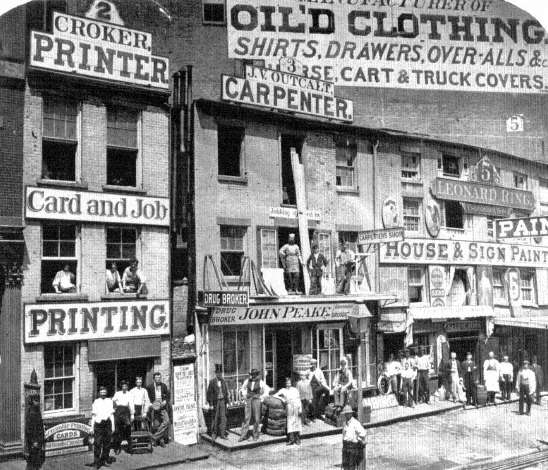

29. Hudson Street, New York, ca. 1865. The big-city hive of small shops. New-York Historical Society

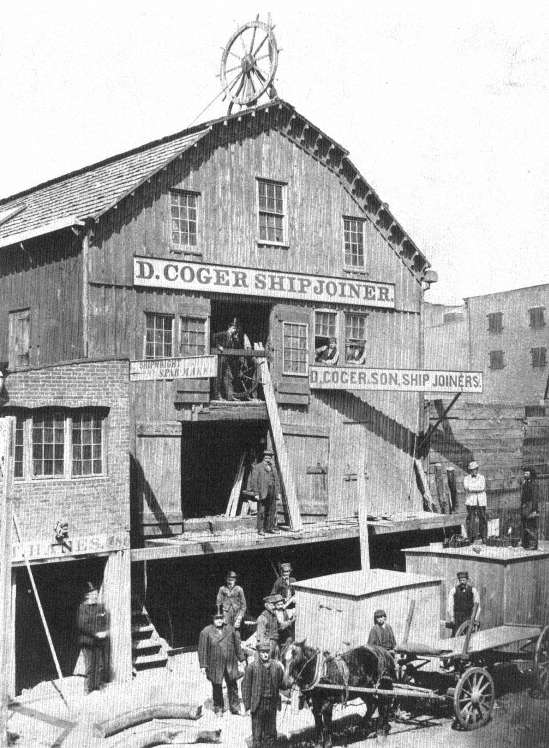

30. 480 Water Street, New York, ca. 1863. In the preindustrial era, barns and churches were the commonplace large structures. Here, a typical barnlike building serves as factory for a ship joiner making deckhouses. New-York Historical Society

31. Wall Street, New York, ca. 1878. A Sunday, presumably, at the heart of American finance, the small scale of early capitalist concentration. New-York Historical Society

Transportation

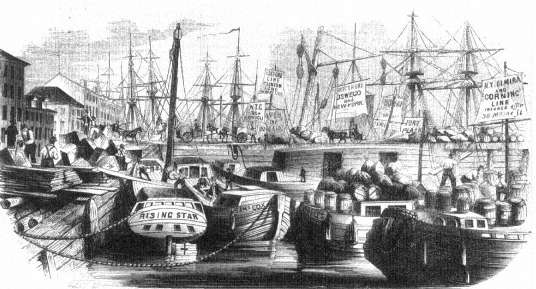

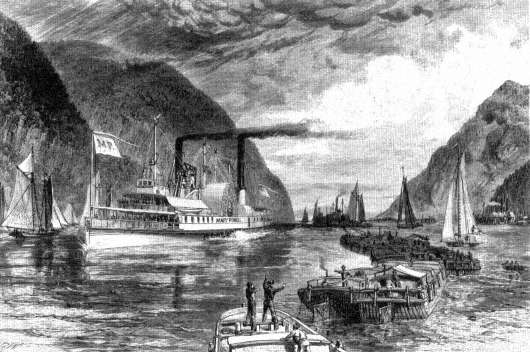

32. Coffee-House Slip, New York, 1830. Packet Lines offering abundant regulary scheduled sailings from New York to European and East Coast ports were a key to the city's mercantile supremacy. Eno Collection, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations

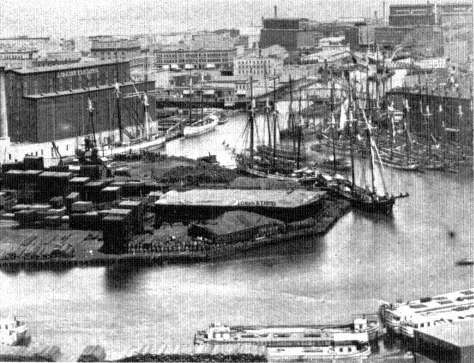

33. Canal Boats, New York, 1852. Before the organization of wholesale lumber districts and grain elevators, shippers and canal boats carried small lots of farm and forest products to regional trading centers for manufacture and processing. New-York Historical Society

34. Highlands of the Hudson River, 1874. River artery of early industrial economy: sloops, schooners, canal boats under tow, the Albany-New York dayliner Mary Powell on the first New York thruway. New-York Historical Society

35. South Street, New York, 1880s. Square-riggers and small merchant warehouses, Atlantic links of the nation's first big city. New-York Historical Society

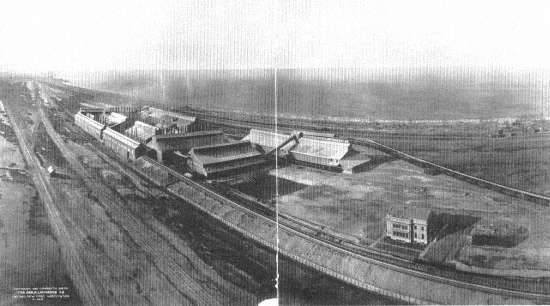

36. Grand Central Station at 42nd Street, New York, 1875. A deceptively small and elegant Paris-style hotel façade conceals the overarching power of the intercity railroad network. This new transportation system remade New York's economy into a national industrial metropolis, adding manufacturing to its established functions of finance and commerce. New-York Historical Society

37. Interior of Grand Central Station, New York, 1885. Such passenger train sheds were seen by contemporaries as symbols of the force of a new era. "What forces, what fates, slept in these bulks (great night trains lying on the tracks) which would soon be hurling themselves . . . through the night!" William Dean Howells, A Hazard of New Fortunes (1890). The French Impressionist Claude Monet painted seven scenes in and around Gare Saint-Lazare (1876-77), manifesting the same spirit. New-York Historical Society

38. General Motors Plant, Linden, New Jersey, 1967. Early nineteenth-century canal and railroad alignments permanently laid down the basic industrial skeleton of today's Northeastern megalopolis. Here, an auto assembly plant, fifteen miles from Manhattan along the old New York-Philadelphia transportation axis, U.S. Highway No. 1 (left) and Penn Central Railroad tracks (right). Regional Plan Association, Louis B. Schlivek

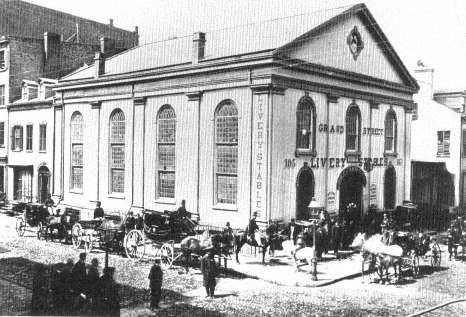

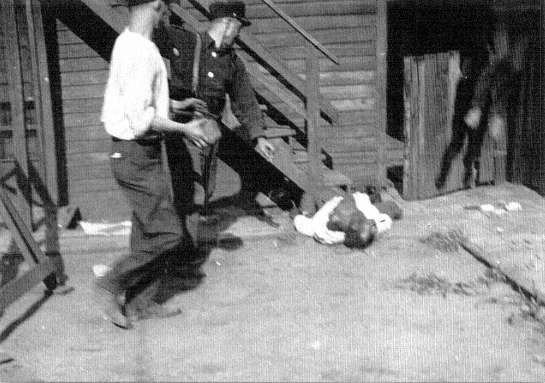

39. Grand Street Livery Stables, New York, 1865. The livery stable was the back-up transportation equivalent of today's truck and auto rental chains.

Their flies, manure, and smell were the bane of every neighborhood. New-York Historical Society

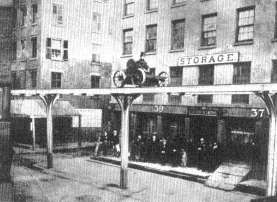

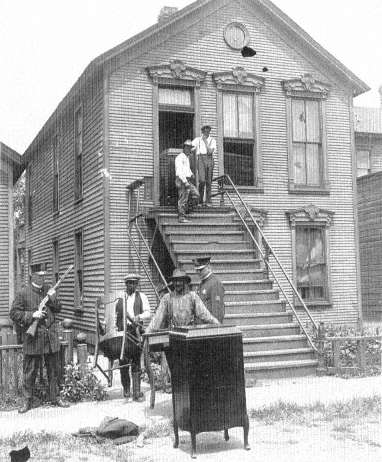

40. Greenwich Street Elevated, New York, 1867. Inventor of a cable-drawn engine, Charles T. Harvey, tries it out on the city's first el. New-York Historical Society

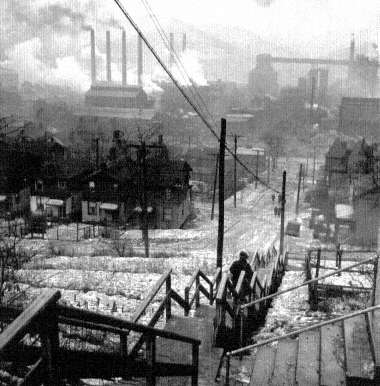

41. Greenwich Street Elevated at Ninth Avenue, New York, 1876. Typical American failure to adapt transportation innovations to the city's inherited framework. Here, old West Side working-class and industrial quarter is attacked by the new transit system. New-York Historical Society

15.

New York, 1849

16.

Boston, 1855

17.

San Francisco, 1850-51

18.

Broadway, New York, 1834

19.

Broadway, New York, 1870s

20.

Hudson Square, New York, 1866-67

21.

Fifth Avenue from 28th Street, New York, 1865

22.

Working-Class New York, Canal and Mott Streets, ca. 1870

23.

West Washington Market, New York, 1880s

24.

West 133rd Street, New York, ca. 1877

25.

Fifth Avenue, 116th and 117th Streets, New York, 1893

26.

168-172 Fulton Street, New York, ca. 1820

27.

512-514 Broome Street, New York, 1935

28.

Coenties Slip, New York, ca. 1879

29.

Hudson Street, New York, ca. 1865

30.

480 Water Street, New York, ca. 1863

31.

Wall Street, New York, ca. 1878

32.

Coffee-House Slip, New York, 1830

33.

Canal Boats, New York, 1852

34.

Highlands of the Hudson River, 1874

35.

South Street, New York, 1880s

36.

Grand Central Station, New York, 1875

37.

Interior of Grand Central Station, New York, 1885

38.

General Motors Plant, Linden, New Jersey, 1967

39.

Grand Street Livery Stables, New York. 1865

40.

Greenwich Street Elevated, New York, 1867

41.

Greenwich Street Elevated at Ninth Avenue, New York, 1876

none, he has friends in the village, and ere a year, Bill, Jo and Jim have been seduced off to New York.[21]

Unlike European countries of the time, the United States was an undeveloped land of bounteous resources which sustained a severe shortage of skilled labor. It offered high rewards to men who practiced a craft, and foreign-born artisans became leaders in many of the crafts in America. German immigrants predominated in New York in such diverse trades as sugar refining, the making of pianos and guns, and in lithography. Watchcase makers came from France and Switzerland, glass cutters from Ireland; ship riggers were Swedish, machinists British.

Urban production for a widening market also implied dependence upon a national and an international economy in a way that earlier artisans had never known. There were boom times, but there were also busts, panics, and depressions that caught all America and its London bankers short of orders, money, and credit. At such times wages might plummet 30 and 40 percent in a year's time. It has been estimated that a third of New York City's work force became unemployed in the panic of 1837. The depression in the winter of 1854-55 caused such widespread misery that a relief group claimed 195,000 men, women, and children were in want.[22] With every decade the cities burgeoned and intertwined more tightly with the rest of the United States and the world, so that each swing of depression meant longer breadlines, more evictions, more pervasive suffering.

The increase in the scale of production and the reach of markets started a long process of division into two classes within the urban labor force. The new discipline of urban work harassed and enticed Americans into a permanent acceptance of a social division between hand workers and pen wielders, operatives and clerks, the blue collar and the white. The pace of market growth was so fantastic that it impelled the enlargement of family shops and those with four or five employees to establishments with a dozen, fifty, even hundreds of workers. A number of results could be seen at once: the introduction of strict discipline and the systematic exploitation of women and children, the breakdown of

[21] . Walter Barrett (pseud. Joseph A. Scoville), The Old Merchants of New York City , New York, 1865, pp. 57-58. Note that this same spirit of youthful energy for moneymaking and success also characterizes the Lithuanian immigrant Jurgis Rudkus in Upton Sinclair's anticapitalist novel The Jungle (New York, 1906).

[22] . Ernst, Immigrant Life , pp. 73-83.

complex craft skills into simple repetitive tasks, the drive for quantity by cutting piecework rates and by the introduction of machinery. Simultaneously a whole new class appeared—the well-to-do class of owners and partners who always enjoyed prosperity far beyond their employees and sometimes attained the undreamed-of wealth of a John Jacob Astor, a Peter Cooper, or a Cornelius Vanderbilt.

The widening gulf between classes by no means went unnoticed by contemporaries. From the first, workingmen of the largest cities protested the loss of control over their working lives, and to combat it they formed unions. In the 1820s and 1830s, early in the process of differentiation between boss and worker, some unions included masters and shopowners who sympathized with the men or were themselves oppressed by wholesale competition. The great Ten-Hour movement of the thirties appeared as a wave of enthusiastic strikes and parades and swept the Eastern coast cities. It sought relief from the unbroken sun-rise-to-sunset hours that had once been only seasonal or rush practices and asked for reduction in hours without reduction in pay.

It was the depression of 1837-39 that broke the power of the workingman and his new organizations. Subsequent hard times and panics, as well as the counterorganization of employers, attacked later revivals of unionism. Only a few highly skilled unions seemed able to establish themselves permanently, groups like the printers, cigar makers, iron molders, and the members of some of the building trades. Though the union movement as a countervailing force to business reorganization remained endemic throughout the nineteenth century, everything worked against it: the steady erosion of craft skills and the consequent weakening of the bargaining power of the men, the growing influx of foreign labor and the ceaseless coming and going of all working groups in a restless search for decent wages and better conditions, the competitive and exploitative use of women and children and untrained immigrants, and the expansion of business that put more and more wealth and political influence into the hands of employers in labor disputes. The same factors worked against the men's attempts to set up producers' cooperatives and other social experiments, while the working-class political parties were destroyed by competition with another social outgrowth of this era, the urban political machine. The machine could successfully undercut the labor parties by delivering jobs and opportunities to its faithful party workers at the same time that it was giving

verbal support to workers' platforms.[23] Indeed, it has long been one of the major functions of American politics to blur class conflicts in order to appeal to the broadest possible coalition of voters.[24]

The very fact that the early nineteenth-century trend toward widening social distinctions between working class and middle class was a reversal of former preindustrial tendencies made the process all the more painful. During and after the Revolution, the urban artisan had gained a growing measure of political participation and power. Jacksonian democracy rose on the momentum of these years, only to collapse as social conditions in factories, cities, and farms undermined its dependence on a vanishing social reality of independent artisans, shopkeepers, and farmers.

In the period between 1776 and 1820, America seemed to be moving toward a growing egalitarianism. In the old commercial cities of the time, cities of small shopkeepers and merchants, the lines between worker and owner were blurred despite an obvious coexistence of rich and poor and the prominence of families of long-standing privilege and influence. Then beginning in the 1820s, as business quickened and harsh methods spread, the benign trends reversed themselves and the inexorable advance of blue-collar-white-collar distinctions commenced. Despite the unions, parades, strikes, and political parties that centered on the workingman, the hand worker lost ground. He lost status, he lost assurance of employment, and he lost personal control over his work. Ensuing waves of frustration and anger broke over the city. All the big cities suffered epidemics of violence; there were labor riots, race riots, native-foreign riots, Catholic-Protestant riots, rich-poor riots.[25] New York City alone underwent a succession of riots, eight major and at least ten minor, between 1834 and 1871. The climax came in 1863 as a mixed class and race riot, begun in protest against the draft, exploded among the city's workingmen and poor Irish.

[23] . Commons, History of Labour , I, pp. 169-84; Norman Ware, The Industrial Worker 1840-1860 , Boston, 1924, pp. 18-70.

[24] . For example, the industrialist Peter Cooper, like many Americans of his time, mixed Jacksonian antibanker, popular democratic ideas with strong anti-foreign, anti-Catholic and staunch probusiness politics. See Robert P. Sharkey, Money. Class and Power, An Economic Study of Civil War and Reconstruction , Baltimore, 1959, pp. 276-84; and Edward C. Mack, Peter Cooper , New York, 1949, pp. 357-72.

[25] . Hugh B. Graham and Ted R. Gurr, Violence in America: Historical and Comparative Perspectives , New York, 1969, pp. 53-55.

Early in the morning men began to assemble here [on the West Side] m separate groups, as if in accordance with a previous arrangement, and at last moved quietly north along the various avenues. Women, also, like camp followers, took the same direction in crowds. . . . The factories and workshops were visited, and the men compelled to knock off work and join them, while the proprietors were threatened with the destruction of their property, if they made any opposition.

A ragged, coatless, heterogeneously weaponed army, it heaved tumultuously along Third Avenue. Tearing down the telegraph poles as it crossed the Harlem & New Haven Railroad track, it surged angrily up around the building where the drafting was going on. The small squad of police stationed there to repress disorder looked on bewildered, feeling they were powerless in the presence of such a host. Soon a stone went crashing through the window, which was a signal for a general assault on the doors. These giving way before the immense pressure, the foremost rushed in, followed by shouts and yells from those behind, and began to break up the furniture. The drafting officers, in an adjoining room, alarmed, fled precipitously through the rear of the building. The mob seized the wheel in which were the names, and what books, papers, and lists were left, and tore them up, and scattered them in every direction. A safe stood on one side, which was supposed to contain important papers, and on this they fell with clubs and stones, but in vain. Enraged at being thwarted, they set fire to the building, and hurried out of it. As the smoke began to ascend, the onlooking multitude without sent up a loud cheer.

The scene in Third Avenue at this time was fearful and appalling. It was now noon, but the hot July sun was obscured by heavy clouds, that hung in ominous shadows over the city, while from near Cooper Institute to Forty-sixth Street, or about thirty blocks, the avenue was black with human beings,—sidewalks, house-tops, windows, and stoops all filled with rioters or spectators. Dividing it like a stream, horse-cars arrested in their course lay strung along as far as the eye could reach. As the glance ran along this mighty mass of men and women north, it rested at length on huge columns of smoke rolling heavenward from burning buildings, giving a still more fearful aspect to the scene. Many estimated the number at this time in the street at fifty thousand.[26]

For four days mobs of workingmen and lower-class citizens broke into the stores and homes of the rich, beat and killed policemen, and fought pitched battles against the companies of police and militia. They broke into the armories, felled telegraph poles, and closed off streets by means of cobblestone barricades. The city police and the troops who were rushed back from Gettysburg quelled the riot but only after the city

[26] . Joel T. Headley, The Great Riots of New York: 1712-1873 , New York, 1873, reprint, Indianapolis, 1970, pp. 160-61, 164.

had suffered casualties estimated as high as two thousand killed and eight thousand injured. If the estimates are accurate, they would make the casualties of the New York Draft Riots equivalent to the losses at Shiloh or Bull Run.[27]

Unquestionably these riots, likened by contemporaries to the uprising in Europe in 1848 and later to the Paris Commune of 1871, frightened generations of wealthy Americans. The idea of a class war between worker and capitalist, though never widely adopted despite energetic Marxist indoctrination, became an indelible part of the thinking of the wealthy at least until the Second World War. But there was a more immediate and progressive consequence of the riots: the undertaking of a systematic investigation into urban living conditions.

What were these early big cities of America like?

They were a crowded jumble of small buildings organized as yet by only the most primitive specialization of land use. Imagine a city of half a million or even a million inhabitants in which church steeples stood out on the skyline and the masts and spars of ships at the wharves could be seen above the roofs of warehouses and factories. As yet there were no giant manufacturing lofts or skyscrapers to house offices and stores, partly because the techniques for erecting such structures had not been perfected but also because there was as yet no pressing need for them. The downtown office of the mid-nineteenth century consisted of one to three partners and a few clerks. The unique downtown institutions of this era were not skyscraper banks or corporate office towers but the Merchants' Exchange and the Stock Exchange, the settings for periodic gatherings of businessmen who met each day to transact their business together. A big daily newspaper office and plant, like Horace Greeley's Tribune , fitted on a downtown street in a modest five-story building, one of several in a row that made up the block. The factories in which the new discipline and new machines were being introduced were for the most part small affairs. They might be housed in a floor or two of an ancient narrow building belonging to a merchant, in a basement, in a rear-yard structure of one or two stories that resembled a barn, or perhaps, in some trades like the making of cigars or clothing, in the tenement room of the worker himself.

Capacious factories and shipyards did stand at the edge of the city, but the modest spatial demand of most business enterprises meant that

[27] . Herbert Asbury, The Gangs of New York, An Informal History of the Underworld , London, 1928, pp. 169-70.

they could be served by one or a few building lots. Accordingly, every part of the city contained shops and small factories. Let us look at New York's fashionable Washington Square as examined in detail after the Draft Riots. Doctor F. A. Burrell of 22 West Eleventh Street, who conducted the inspection, reported a population of 27,587 in the area (the Fifteenth Ward), occupying almost three thousand buildings: "The style of living of the population presents every variety from luxury to poverty, and almost every branch of industry is represented." There were in fact forty-eight factories, which turned out such products as pianos, cabinet furniture, trunks, sewing machines, chocolate, carriages, photographic materials, and hoopskirts, and there was one slaughterhouse and one soap and candle factory. The survey also identified 542 "stores" of all kinds and 234 "dram shops" (which we would now call bars), 23 "lager bier saloons," 17 gambling saloons, 7 concert saloons, 76 brothels, and 22 policy shops.[28] Hardly the modern bourgeois residential style.