6

The income of the town as a separate economic unit came from its agricultural production and the value added to goods and services it sold

outside. The net harvest after deduction for seed was 3,606 EFW, the gross income from livestock 353 EFW (Table 7.8). The arrieros brought in most of the income from outside. While they transported some of the local harvests and brought in goods, most of their services were rendered to others. It seems reasonable to attribute 75 percent of their gross income from haulage (2,370 EFW) to outside sources: 1,780 EFW. If three-quarters of their income from trading mules also came from outside, this was another 43 EFW. It is possible that the linen weaver and the shoemaker sold some goods outside the town, but their incomes were so small that they hardly added to the total.

Against these incomes one must charge the payments made outside the town. These included rent on the fields owned by nonresidents, on pastures in adjoining despoblados, and on pastures used by the arrieros while on the road, as well as the cost of the fodder they bought while traveling, all of which have already been calculated. It was likely that vecinos of La Mata and its church owned as much land in neighboring towns as vecinos and churches of those villages owned in La Mata, so that rent received from nearby farmers would offset the rent paid for land in neighboring towns (about 23 EFW). This amount can be subtracted from the rent paid outsiders (575 EFW; Table 7.8), while none of the rent paid to local churches will be charged against the town.

A good proportion of the payments to the church also left the town. Two-ninths of the partible tithes of Castile had been granted to the king by the pope in the thirteenth century. Known as the tercias reales, the grant was extended to all Spain and made permanent in 1487.[66] In La Mata and other places around Salamanca, these now went to the University of Salamanca by royal cession (87 EFW, Table 7.3). In addition another third of the partible tithes (131 EFW) belonged to the prestamo, a form of ecclesiastical perpetual right, whose current holder was a member of the faculty (maestre de escuela ) of the university.[67] These beneficiaries had to pay their share of the cost of collection and storage of the tithes, and this expense remained in the town economy. The holder of the prestamo was also entitled to one-third of the first fruits (9 EFW), while, as described earlier, various institutions received horros in lieu of tithes on the crops of their fields, the tithes of the cuarto dezmero went directly to the cathedral, and the Voto de Santiago to the archbishop of Santiago de Compostela through his local agent. After the local benefice took its third of the partible tithes, the local fabric received the remain-

[66] Desdevises, L'Espagne 2 : 369.

[67] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 15.

ing ninth.[68] Besides the tithes of the villagers of La Mata, its church also received those of the neighboring despoblado of Narros, which was an anexo of the parish. These totaled 97 EFW[69] and had the same destination as the partible of La Mata: five-ninths left the town. A good part of the ninth paid the fabric as well as the rent of the fields belonging to the parish church (exclusive of those of the benefice) must have been spent outside the community for supplies for the church and religious services, perhaps 25 percent (28 EFW).

Finally the village as a civil unit met specific annual impositions. Fifteen fanegas of wheat went to the city of Salamanca as La Mata's obligation under a foro perpetuo, a form of feudal dues.[70] The village also paid one fanega of wheat to the convent of Calced Trinitarians of Salamanca, "they do not know for what reason."[71] Then there were royal taxes, thirty reales (2 EFW) for the servicio ordinario y extraordinario y su quince al millar (a direct levy consented to by the Cortes of Castile under the Habsburg kings, for which most towns had since compounded at a fixed annual payment [encabezamiento]) and five hundred reales (36 EFW) for sisas, an excise tax on certain consumer goods that had also been compounded for and that the tavernkeeper now paid for the town.[72] The payments made by the town council could be met by the rent on its buildings and fields.

From this information one can strike a balance for the net annual income of the community of La Mata, as done in Table 7.14. The figure is 4,683 EFW.

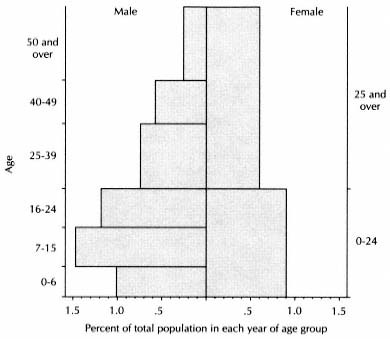

To convert the net town income into a per capita income, one must determine the population of La Mata at the time of the catastro. The libros personales list the members of each family, with the ages of the males. One can estimate the ages of the females by their marital status and the age of their fathers, brothers, husbands, or sons. In this fashion one finds a total population of 225 divided into age groups as shown in Table 7.15 and Figure 7.4.

To check the accuracy of this table, one can compare it to the census of 1786, using both the return of La Mata and of the medium sized towns of the Armuña region, shown in Table 7.16. The demographic structures in 1786 suggest that the catastro failed to record a number of young females and perhaps also some males under seven. To correct

[68] Ibid.

[69] AHPS, Catastro, Narros de Valdunciel, libro 2559, resp. gen. Q 16.

[70] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 23.

[71] Ibid. Q 26.

[72] Ibid. Q 29.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 7.4.

La Mata, Population Structure, 1753

Note: Since there is no limit to the top age groups, a span

of seventeen years for males is used for convenience only.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

these omissions, I shall consider the catastro complete for males over sixteen and females over twenty-five. In the table for Armuña in 1786, these groups represent 53.1 percent of the population. In the catastro of La Mata, these groups total 129 persons; and if these are 53.1 percent of the total, the total is 243, or 18 more than the catastro recorded. The same operation using the 1786 structure of La Mata yields a figure of 260 for the 1753 population. It appears probable that the catastro did underenumerate young people, and we can use 243 as a minimum population in 1753 and 260 as a maximum.

Dividing the net town income from Table 7.14 (4,683 EFW) by these estimates, one obtains a per capita income of between 18.0 and 19.3 EFW per year. This was half again more than the 12 EFW per capita that I have estimated provided an adequate subsistence for the rural Spanish population.

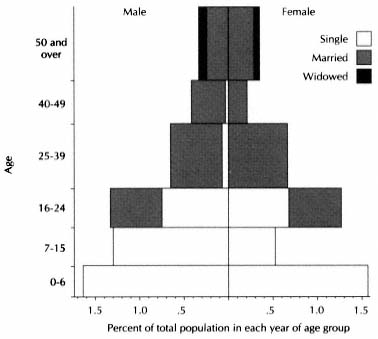

In addition, the censuses reveal an indirect source of income that the catastro could not record. A population beehive of the town in 1786 shows a remarkable shortage of females between seven and fifteen (Fig-

Figure 7.5.

La Mata, Population Structure, 1786

NOTE : Since there is no limit to the top age group, a

span of seventeen years is used for convenience only.

ure 7.5).[73] There were forty boys and only sixteen girls in this age group. Even allowing for underenumeration, one can be reasonably sure that there was a shortage of unmarried girls in 1786, and this phenomenon was probably already present in 1753. In all likelihood their absence is evidence of a practice of sending girls to serve in the city, with the intention of returning to marry when they reached the proper age.[74] Meanwhile they represented fewer mouths to feed, and their labor, unlike that of their brothers, was not needed in the fields or on the road.

In the middle of the eighteenth century, La Mata was a prosperous town of some sixty families. All thirteen labradores, all but one of the twenty-four arrieros, and the priest, altogether two-thirds of the households, had incomes that allowed them to live with ease. Of these at least

[73] For the data of the 1786 census of La Mata, see Appendix N, Table N.6.

[74] See Scott and Tilly, "Women's Work," for an analysis of this widespread practice in the nineteenth century.

nine labradores, eight arrieros, and the priest earned twice or more what their families needed for an adequate standard of living. The tavernkeeper and surgeon-bloodletter turned a fair penny, and only the large size of their households kept their per capita income from being among the higher levels. Most of the other families, headed by artisans, jornaleros, herders, and widows, no doubt supplemented their direct income by tilling a small plot as a senarero or doing odd jobs for others or for the church or the town council. The town profited from a dual economy based on agriculture and muleteering. The income of the arrieros represented about 6.5 EFW per capita. Had these men been engaged in agriculture, even if in so doing they had increased the harvests through more intensive cultivation, the per capita income would have declined to close to the adequate mean. Their activity made possible the flourishing economy of the town in the face of the small extent of land per vecino.

This little community would have warmed the hearts of the Madrid reformers. It is true that its vecinos did not live on separate, enclosed homesteads or own their own land as the reformers propounded, but they had fairly stable, assured leases, which allowed them to make a comfortable living and produce a healthy excess for the market. They could keep six fanegas of wheat for each person in the community and all the other grains and pulses from the harvest and still leave two thousand fanegas of wheat to export, as rent, as tithes, or for their own account. Fewer than four hundred such communities, one hundred thousand people in all, could supply all the wheat Madrid needed. Campomanes recommended that rural communities introduce domestic manufactures that would use local raw materials and give remunerative occupations to the women and children.[75] Although we do not know what the women and children did in their homes, La Mata had no active artisan sector, but the arrieros did provide a mixed economy and were responsible for the substantial margin of well-being of the community as a whole. If all arid Spain had been like La Mata, agricultural reform would never have become the dominant domestic issue of the last decades of its old regime.

For their well-being, the people of La Mata paid with the timeless labor of rural folk. The labradores, their jornaleros, and their sons hitched their oxen to their plows and worked their tiny scattered plots in the cold winds of the winter and early spring; later they bowed under the parching July sun to harvest the ripe wheat with their sickles and

[75] Rodríguez de Campomanes, Industria popular.

rode their heavy threshing boards behind their oxen round and round the town threshing floor, the eras, to separate the grain from the chaff—a task in which wives and children could join—loaded their carts or animals in August with the wheat they owed their landlords in Salamanca and in the fall cared for their newborn lambs and slaughtered their pigs. The arrieros heaved the bags of grain on their mules and donkeys after the harvest, heading for the main regional markets or setting out on the long journey north to Burgos and Bilbao, walking beside their beasts in all kinds of weather, unloading in the evening and loading again in the morning the goods that provided their livelihood. They returned in time for Christmas but set out again as soon as the roads were passable, getting home once more for the June fairs. Following the local custom, the arrieros of La Mata traveled together for security and company. They helped each other and needed few additional hands, and their sons stayed to work for other vecinos until they were ready to set up in their fathers' trade. Then they would join the group to learn the routes and the best pastures and watering holes.[76] Meanwhile the wives kept the hearths alive, prepared the thick bread soup of breakfast and supper, washed and mended the clothes, and in the fall made the farinato sausages of pork and crumbs.[77] The daughters of the poorer families spent their adolescence serving in the city, and the widowed grandmothers took care of the children too young to work.

Religious holidays solemnized the revolution of the seasons that marked the life of La Mata. The town council's budget provided 110 reales for a preacher in Lent, possibly a friar from Salamanca, and another 60 reales for the parish curate to say extraordinary masses on other occasions.[78] The parish had four confraternities that supported special services out of the income provided by the lands they owned. They were dedicated to Corpus Christi (ten weeks after Easter), Saint Michael (29 September), Our Lady of the Rosary (7 October), and All Souls (2 November).[79] These were all occasions for pageantry, but they could not compare with the town fair of 26 June, the feast of San Pelayo, patron of the parish.[80] Then the grain fields were almost ripe, and

[76] On the lives of the arrieros, Cabo Alonso, "La Armuña," 127–29. The author's source is evidently the community memory, for he is a native of La Mata.

[77] On the soup and farinato sausages, Cabo Alonso, "Antecedentes históricos," 81–82.

[78] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 25.

[79] Cofradías del Santísimo, de San Miguel, de Nuestra Señora del Rosario, and de Animas, La Mata, maest. ecles., ff. 64–77.

[80] The parish was named San Pelayo Magno, according to the census return of 1786.

the farmers knew if the harvest would be plentiful. The muleteers had returned from their spring trip with wares to hawk—iron tools and copper and brass pots and pans from Basque forges, perhaps woolens from northern Europe. Vecinos of nearby towns brought livestock to trade. Solemn mass and the inevitable procession sanctified the occasion, a symbiosis of religion, business, and festivity.[81] Different but equally central to the year's course was the day in August when the vecinos who harvested grain paid their tithes "to God our Lord," as the catastro says, and the earthly vicars who received them for Him provided refreshments for the parishioners.[82] To judge from the tithe rolls of the end of the century, the farmers followed an accepted custom in delivering their holy dues. The larger tithers held back, letting those with smaller harvests settle their accounts with the cillero. As the day advanced one or two labradores would come forward among the senareros. Then as the procedure neared the end, the wealthy farmers produced their large contributions, until all had paid except a few who farmed on the side and now closed the accounts with their pittances. On these occasions Francisco Rodríguez, the tavernkeeper, must have dispersed a good share of the 800 reales' worth of wine he imported each year.[83] Religion dominated the public life of the community, and the figure who embodied religion for the people was don Juan Matute, the priest. More than anyone else, he was the hinge figure of the community, their procurator before the outside world, earthly as well as heavenly. The vecinos were conscious of course of the economic differences arising from their varied occupations and incomes—the labradores and arrieros must have had their little rivalries, and they preferred to marry their children to children of their fellows—but except for don Juan, they were socially homogeneous, a close community ruled by tradition and the demands of the seasons.