One—

Colonizing Souls: The Failure of the Indian Inquisition and the Rise of Penitential Discipline

J. Jorge Klor de Alva

When you tell someone your secret, your freedom is gone.

—FERNANDO DE ROJAS, La Celestina

On a November morning in 1539 don Carlos Ometochtzin, the native leader of the former city-state of Texcoco, was taken out of the prison of the Holy Office garbed in the typical sanbenito cloak and cone-shaped hat of the sentenced offender. He was paraded through the streets of downtown Mexico City, candle in hand, to a scaffold surrounded by the multitude that came to witness his sentencing and abjuration, and later to see his strangled body burn at the stake.[1] For the majority of the natives, it would be unfortunate that never again would an anti-Spanish rebel meet his end at such a public spectacle. In less than a decade, the stake where individual bodies were set ablaze was replaced by the local controls of provisors (or vicars-general) of the dioceses or archdioceses[2] and, even more important, by the confessional, its penances, its magical threats, and its very real capacity to command the submission of tens of thousands of wills to the nascent colonial structure. The two related processes alluded to by these events—the failure of the Indian Inquisition and the consequent rise of penitential discipline, whose control mechanisms played a leading role in the colonization of the Nahuas (the Aztecs and their linguistic and cultural neighbors)—are the subject of this essay.

From the beginning of the colonial effort in New Spain, ambivalence about the Holy Office limited its utility as an instrument for the domination of natives. For instance, the movement to exclude the Indians from the authority of the Inquisition reached an early climax in 1540, when the apostolic inquisitor, Fray Juan de Zumárraga, received a reprimand from Spain for imposing the death sentence on the cacique don Carlos.[3]

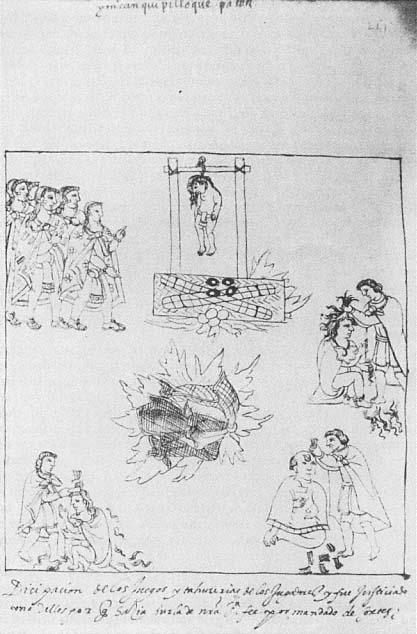

Fig. 1.

Two figures in penitential costume.

The Indians, however, continued to be processed by the Inquisition throughout the decade. And although official warnings to avoid treating the natives with severity were heard, no official prohibition against trying them outside the local dioceses or archdioceses was issued until 1571, when Philip II formally removed the Indians in the Spanish colonies from the jurisdiction of the Holy Office.[4] Despite a previous absence of legislation specifically excluding the Indians, some form of proscription nonetheless existed, because it appears that only one case involving Central Mexican Indians came before the Holy Office from 1547 to 1574.[5] Ambivalence is further suggested by the fact that out of 152 procesos acted upon between 1536 and 1543, the years of greatest inquisitorial

persecution of natives, only about nineteen involved Indians (see Table 1.1) and the number accused was quite small, approximately seventy-five.[6]

Given the seemingly endless possibilities—painfully brought home to us by the experiences of some contemporary nation-states—for forcing subordination through a "culture of terror,"[7] why were so few natives tried, tortured, or executed by the Inquisition? And why was colonial policy so inconsistent that the Indians ended up beyond its grip altogether, although no law demanded that that be the case until 1571, while the need for maximizing control was fully recognized as critical, by both Church and Crown, prior to this date? As is usually the case when spectacular forms of oppression give way to their more subtle varieties, the reasons commonly offered for the Spanish retreat from an aggressive application of such a powerful instrument for subjecting natives have centered on an assumed rising cry of humanitarian sentiment,[8] which is said by some[9] to have echoed the following orders issued in 1540 to the apostolic inquisitor, Archbishop Zumárraga:

since these people are newly converted . . . and in such a short time have not been able to learn well the things of our Christian religion, nor to be instructed in them as is fitting, and mindful that they are new plants, it is necessary that they should be attracted more with love than with rigor . . . and that they should not be treated roughly nor should one apply to them the rigor of the law . . . nor confiscate their property.[10]

But the implementation on humanitarian grounds of these instructions could not have been the primary force that led to the exemption that was generally observed. First of all, the Visitor General Francisco Tello de Sandoval, who replaced Zumárraga in New Spain in 1544 and was responsible for making known the New Laws of 1542—the laws that exhibited the greatest degree of toleration Charles V was able to muster on behalf of the Indians—not only was not instructed to avoid trying natives when acting as apostolic inquisitor but, on the contrary, during his three-year term failed to dismiss the cases against the Indians that came before the Holy Office.[11]

Second, although we know from the effects of the writings of Bartolomé de Las Casas and those of other reformers that this movement could have an influence on the formation of colonial policy,[12] the reform was focused on limited circles during the middle decades of the century and was more successful among Spanish rulers in the Old World than among colonial officials, who had to face the very real wrath of the settlers when they ventured arguments on behalf of the Indians. Fur-

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

thermore, in the New World much if not most of the legislation that favored the indigenes over Spanish interests was generally disregarded or selectively applied.[13] As a consequence, the disputes of the intellectuals, particularly those that took place in Spain,[14] had very limited practical significance in New Spain unless they reflected policy implications that supported the powerful sectors that ruled the colony. These facts point to the difficulties that undermine any categorical conclusion concerning the timing and role played by the toleration movement in the collapse of the Indian Inquisition. Thus, when it comes to measuring the relative strength of the forces that acted to remove the Indians through the Holy Office, it may be more profitable to pay attention to the everyday exigencies of colonial control than to the royal fiats or the juridical or theological arguments that sometimes informed them.

The Inquisition and the Economy of Punishment

Although its ostensible function was to safeguard the orthodoxy of the faith, the Holy Office was recognized to be and constantly was used as an important tool for social and political control since its founding in the thirteenth century.[15] In the New World the history of the Inquisition is primarily the story of the struggles over power and truth that marked the changing fortunes of the various ethnic, racial, and social sectors.[16] Following the defeat of the Mexicas of Mexico-Tenochtitlán in 1521, Cortés and the Franciscan friars put the Holy Office to work to secure their predominance over both upstart Spaniards and recalcitrant Indians. By the surprisingly early date of 1522 an Indian from Acolhuacán appears to have been formally accused of concubinage, thereby becoming the first person in Mexico to be tried by an agent of the Holy Office.[17] This presaged the use of inquisitorial punishment to regulate the behavior of Indians and Europeans that was generalized the following year, when two regulations were issued whose topics fit well into the hands of the Cortesian band. One edict, aimed at Europeans, opposed heretics and Jews; the other, whose vagueness was more a license to prosecute than a guide to proper behavior, was "against any person who through deed or word did anything that appeared to be sinful"![18]

In New Spain the regulatory possibilities of the latter ordinance were especially clear to those who interpreted the culture of the Nahuas as a satanic invention, and who used this as a justification for persecuting indigenous religious and sociocultural practices as criminal. Indeed, as the military and political hegemony of the Spaniards solidified, this popular interpretation was implemented as an apparatus of control by turning

Fig. 2.

"Discipline of players and gamblers and punishment of one who

had ridiculed our holy faith, by order of Cortés."

social customs and beliefs, acceptable in the native moral register, into sins, subject to temporal and symbolic punishment according to the Spanish criminal/canonical code. The tracing of both European and New World moralities onto the same penal map resolved the problem of cross-cultural (national) jurisdiction immediately. Thus, the Franciscan friar Martín de Valencia, who read into many aspects of the native cultures the authorship of the Devil, began to persecute recently baptized Indians in his capacity as commissary of the Holy Office immediately after his arrival in 1524. By 1527 his zeal was such that he had four Tlaxcalan leaders executed as idolaters and sacrificers,[19] even though the previous year the Franciscans had lost control of the Inquisition to the Dominicans.[20] In turn, the Dominican leaders of the Holy Office lost no time setting the institution to the task of stopping Cortés and his Franciscan allies from monopolizing the mechanisms of social and political domination; they sought to accomplish this power shift primarily by processing scores of their rivals as blasphemers.[21] However, with the arrival of the first viceroy in 1535, and the initiation of Zumárraga's episcopal tribunal the following year, the attention of the Holy Office shifted from the highly partisan contests between Spaniards[22] to the need to organize a colonial society primarily out of Nahuatl-speaking Indians.

It is hard to imagine a more difficult project: political and religious resistance, demographic ratios, language barriers, cultural distances, and extensive geographic spaces stood in the way, and the Spaniards had few precedents they could follow with confidence. Neither the confrontations with heretics, apostates, or non-Christians back home, nor their experiences with the far less socially integrated tribal and chiefdom communities in the circum-Caribbean area, prepared the Spaniards for the encounter with the city-state polities of New Spain. In Central Mexico cultural, regulatory, and security concerns contrasted sharply with those faced in Spain; there, not only did a variety of effective mechanisms of social control exist that could not be duplicated in the New World, but the problems of ethnic diversity in the peninsula tended primarily to affect civic unity rather than to challenge political stability or cultural viability, as was frequently the case in Mexico.

Consequently, from the time of the fall of Tenochtitlán, the primary requirement for the establishment of a colony was tactical and ethnographic knowledge, which called for the development of new disciplinary and intelligence techniques.[23] To gain control, the Spaniards needed information about the topography and natural resources of the land, the

political and social organizations and their jurisdictions, the geography of economic production, the type and extent of religious beliefs and rituals, the meanings and implications of ideological assumptions and local loyalties, and the nature and exploitability of everyday practices. All these data had to be elicited, translated, interpreted, and ordered within familiar conceptual categories that could make practical sense of the land and the people in order to form the New Spain out of highly ethnocentric and aggressively self-interested city-states.

To this effect, what today would be called ethnography drew the attention of some of the early conquerors (particularly Cortés himself),[24] priests, and secular officials, so that by the early 1530s missionary-ethnographers were formally instructed to collect the information needed to found a productive and peaceful colony.[25] Of the various institutions charged with the creation of new knowledge about the Indians, the Inquisition seemed to hold the most promise. After all, it enjoyed overwhelming support on the part of Church and Crown, and it appeared to have access to the maximum force needed to extract confessions, draw forth information, and punish those who remained silent or otherwise resisted its claims.

A close study of trial records nonetheless suggests that the efficacy of the Holy Office as a punitive system and the quantity and variety of information the inquisitors could elicit were limited by a number of factors. First, quite apart from the ruses and manipulations that sometimes precipitated inquisitorial accusations (denuncias or informaciones ), charges were formally restricted to the types of crimes and breaches legally recognized as within the competence of the Holy Office. These included a significant but extremely small number of categories of acts that needed to be controlled by the colonial powers (see Table 1.2, A). Second, there were legal restraints upon the interrogative procedures used that made it difficult for important but excludable information to enter the record. Third, the extreme and public nature of the penalties could serve as a warning to many but did so at the price of moving the key rebels who resisted the colonial order further underground, where it became more difficult to uproot them.[26] Fourth, the cultural and demographic barriers between Indians and Europeans, the Holy Office's legalistic procedures, and the Inquisition officials' constant concern with status—all called for levels of financing, energy, and personnel that spelled the need for the institution to focus its attention and resources on what it knew best and ultimately feared most: heresy and deviance among Europeans. Not surprisingly, of the 152 procesos tried by Zumárraga's tri-

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

bunal, ninety-three were for crimes associated almost exclusively with Europeans: blasphemy, heresy, Judaizing, and clerical crimes (Table 1.2, B).[27]

Together, these restrictions contributed to making the Inquisition a poor mechanism for meting out the type of punishment needed to effectively regulate masses of unacculturated Indians. But what ultimately marginalized the Holy Office from the efforts to subjugate the native populations was the widespread deployment, during the first half of the century, of two related practices: sacramental confession and missionary ethnography. Because each of these was far more pervasive and intrusive than the Inquisition, together they were more efficient at gathering the kind of information needed to transform the Nahuas into disciplined subjects. Elsewhere I take up the role of the penitential system as an inciter of discourse on the self and as an apparatus of self-formation;[28] here my sole concern is to study how, in the first half of the sixteenth century, a shift took place from the inquisitorial techniques of random investigation and selective punishment to a technique of penitential discipline that sought to affect each word, thought, and deed of every individual Indian.

From Punishment to Discipline

The responsibility for the forced acculturation of the Indians moved from the Holy Office to the (seemingly) less stringent local offices of the bishops (known as the provisorato del ordinario ) in 1547 (see Moreno de los Arcos, this volume). The archival record attests to the timing of this de facto shift in jurisdiction because only one relevant case[29] appears between that date and 1574,[30] by which time the Holy Office had already lost its official jurisdiction over the indigenes (see Table 1.1). Although the change of venue is nowhere explicitly explained or noted, the letters sent to Zumárraga in 1540, after he had had don Carlos executed, suggest the outline of a new policy. Translated into today's analytical language, the critical points in the instructions to the archbishop could be summarized—and were justified then—as follows:

1. Punishment, by functioning as part of a regime of exercises aimed at disciplining through indoctrination, is to be discreet and to have the self (mind/soul), rather than the body, as its object. That is, instead of torture, rigorous punishments, or scandalizing executions, what was needed was for the Indians "first to be very well instructed in and informed about the faith . . . because gentleness should be applied first, before the sore is opened with an iron."

2. The source and end of the discipline are to be invisible. For instance, "the little property they possess" should not be confiscated "because . . . the Indians have been greatly scandalized, thinking that they are burned on account of the great desire for these goods."

3. The discipline is to be made imperceptible by appearing to be evenly applied throughout the whole social body. In effect, instead of teaching them a lesson through rigorous persecution, "the Indians would be better instructed and edified if (the Inquisition) proceeded against the Spaniards who supposedly sold them idols, since they deserved the punishment more than the Indians who bought them."[31]

I will continue by analyzing the meaning and implications of each of these points.

Punishment and the Disciplining of the Soul

Scholars have made much of the humanism the first point seems to imply. The call for tolerance is an echo of the arguments developed in the late 1530s by Las Casas[32] to attack the superficial and sometimes violent means with which the Spanish officials and Franciscan friars sought to impose the new faith on the Indians. However, a survey of the

methods used by the missionaries during these early years attests to the futility of Las Casa's appeals for moderation.[33] It could not have been otherwise. The popular idea that natives needed to be treated in a special manner (because they were new to the faith, because they had a weak understanding, or because they were inclined to vice, etc.) originally arose out of very real political exigencies, although the specific conclusions may have been drawn from speculative reflections on ethnographic data or theology. However contradictory, policy was primarily driven by the pragmatic requirements of the colony, although, as is the case today, in official discourse the need to control was frequently masked by lofty language that expounded on the humanity of subordinates.

A particularly vivid example of the rhetorical, rather than empirical, nature of assessments of native capacity to acculturate is suggested by the following fact: almost thirty years after the letters to Zumárraga were written, the priest Sancho Sánchez de Muñón, while advising the king about the need to establish a Tribunal of the Holy Office in the New World, could still argue that

[the Inquisition] would be one of the most important things in the service of God, for use against the Spaniards, mulattoes, and mestizos who offend our Lord [but] for now it should be suspended in what concerns the natives because they are so new to the faith, weak [gente flaca], and of little substance .[34] [My emphasis]

In effect, the movement toward leniency was less the product of the reformers' rejection of the spectacular punishment of criminal acts, which continued for the Indians in an attenuated form at the local provisorato del ordinario level, and more a recognition, on the part of most priests and secular officials, that what colonial order called for most was the eradication from Indian life of the myriad of seemingly banal deviations from Spanish cultural habits and social customs. The friars, in their letters, sermons, doctrinal works, and detailed manuals for confessors, were quick to argue that every gesture and thought, from those associated with sexual life and domestic practice to the magical and empirical procedures employed in agriculture, the crafts, and social relations, had to be disciplined, retrained, and rechanneled, so as (I would add) to serve the interests of those who wielded power in the colony.[35]

To discover and punish these minute illegalities, systematic and pervasive forms of intervention were necessary. In this situation the Inquisition's attention to the scandalous cases of a few indigenous cult leaders[36] was clearly a dangerous and wasteful display of colonial power. Furthermore, too much delinquency went unperceived by most Spaniards and

was primarily confined to the private or local spheres, which were too numerous to be handled with the juridical safeguards called for by the inquisitorial process. Meanwhile, as these minor infractions continued to escape the grip of the authorities, they helped to reinforce and legitimate sociocultural and political alternatives to the habits and practices necessary for the formation of a homogeneous, predictable, and submissive population.

Although the need to impose some form of consistent and uniform discipline had been coming to light since the early 1530s, a substantial division in the Spanish perception of the level and nature of native resistance to Christianity made it impossible to implement one. On the one hand, Zumárraga's Inquisition, charged with defending the assumptions and practices that articulated Hispanic culture, had the debilitating effect of propagating the idea that native heterodoxy continued primarily as a result of heretical dogmatizing by a few indigenous religious leaders. On the other hand, some of the Franciscans, especially Motolinía,[37] a key figure in the Christianization process since 1524, were claiming that the natives were seeking salvation by the millions and were quickly forgetting the beliefs of the past. On one level, these representations were slowly being challenged by the ethnographic studies undertaken during this time, primarily those begun by Olmos in 1533.[38] On another level, the varieties of regional experiences and the urgent need for immediate control were leading some priests to the realization that local knowledge of the Indians was fundamental to the development of the type of discipline capable of forming "docile bodies."[39] If this latter call for widespread, rather than selective and exemplary, intervention had failed, the Indian Inquisition might have continued—as it did for the other more assimilated racial castes.

The Indian Inquisition, however, did end. And, in particular, its demise came about because it had been organized to function only among the baptized, who presumably already shared with the inquisitor the basic idea of what was and was not an infraction. If this is the case, it follows that the Holy Office was ill suited to discipline a people who did not share its basic cultural or penal assumptions. Before the spectacle of the stake could move beyond striking fear in the hearts of the natives to transforming their behavior permanently, they had to know the prohibitions of the Holy Office and accept the illegality of the things prohibited. Only an efficient system of indoctrination could make these prerequisites a reality.

But an effective proselytizing strategy had to go far beyond violent or physical coercion, the performance of baptisms, or the teaching of

the rudiments of the Christian doctrine. It had to penetrate into every corner of native life, especially those intimate spaces where personal loyalties were forged, commitments were assessed, and collective security concerns were weighed against individual ambitions. Thus, "the invasion within"[40] could not be done by scare tactics, whose ultimate result would more likely be resistance than acquiescence, but rather by shifting the moral gears to produce social and political effects that favored the interests in stability and productivity of those in power. An operative indoctrination that could produce such results had to begin with the widespread, but localized, imposition of a constant regime of moral calisthenics through corporal and magical punishments (like the threat of the first of Hell). These exercises, backed by the threat of the provisors, had to have as their aim the retraining of the individual in order for him or her to internalize a Christian form of self-discipline that would ultimately make external force secondary or unnecessary.[41] This intrusive strategy sought to constitute the most discreet punitive mechanism possible: a fear of divine retribution nourished by a scrupulous consciousness of one's wrongdoings. And where this failed, as it very frequently did, it excused the policing intervention of the priest, with his threats of supernatural punishment, corporal penance, and public shaming and ridicule. It also permitted pious neighbors to force the sinner to behave properly by threatening to exclude him or her from the moral and civic community. It was a brilliant experiment in mass subordination: the costly punishment of individual bodies by colonial officials or the Inquisition could be replaced, for the most part, by the economical disciplining of myriads of souls.

The Invisible Origin and Object of Discipline

The authorship and end of inquisitorial punishment were always evident. The source was obvious to all: Spanish hegemony—a force coming ultimately from the same external apparatus that inflicted innumerable other penalties and burdens. To the Indians, almost all of whom remained unacculturated in the 1540s, its ends were equally apparent: to deprive the accused of his or her traditions, the guiding memory of the ancestors, personal liberty and dignity, corporeal well-being and temporal property, and life (or so it must have seemed after the execution of the cacique don Carlos). Since at this early date the crimes the Inquisition sought to punish were not generally regarded as illegalities by the still unacculturated community, the Holy Office depended primarily on

the exercise of power rather than assent. It therefore lacked the legitimacy to turn scandalous punishments into moral lessons.

In contrast, the transparency of the discipline the friars sought to establish had as its source a continuous and permanent project of acculturation at the margins of Spanish life. The ritual origin and legitimating structure of this program of assimilation, which historians traditionally identify as "conversion,"[42] was a baptism which, in the early colonial situation, the friars had effectively transformed into a new social contract. Thus, unlike inquisitorial punishment, which turned the native subject into an object of punitive force, baptism, the voluntary acceptance of a new social pact, could force each party to it to participate as an active agent in his or her own punishment.

On one level, this new social contract was put into effect by the forces that were slowly appropriating for themselves the authority to determine both the rules of civic life and the nature of the new colonial truths. At the points of general concentration, and therefore penetration, these forces appeared in the form of local priests who (genuinely, for the most part) sought the temporal and symbolic (or supernatural) well-being of the Indians. Their good intentions had the rhetorical and emotive capacity to transpose agency, making the initial phases of indoctrination appear to be the voluntary acceptance of new rules of behavior and new codes of belief. Colonial power thus could circulate at a symbolic level that erased in its very movements the origins and ends that drove it. At another level, the new social pact, by resting on the rhetoric of magic,[43] could be enforced by the manipulation of punitive signs,[44] whose supernatural source was continually preached and whose human origin could thus remain hidden from the believers. The source of the new discipline was consequently made invisible by making it appear as if its fountainhead were either the individual, who voluntarily assumed it, or a deity who commanded it from above: Its end, the peaceful subordination to and productive loyalty on behalf of the colonial powers, was reconstituted as the personal quest for temporal well-being and supernatural salvation.

The Ubiquity and Uniformity of Discipline

The letters to Zumárraga underlined how important it was that inquisitorial punishment appear to be justly assessed and evenhandedly applied. As already noted, this was not possible as long as the Holy

Office had jurisdiction over such a culturally heterogeneous population as the one in New Spain. By weaving the new discipline into the personal and public strands of native and Spanish lives, however, the friars could be seen to cover with it all social and cultural sectors. The widespread use of an apparently common Christian doctrine, penal code, and ritual cycle was at the heart of this tactic.

Furthermore, by introducing the Christian sacraments in ways that made them coextensive with the life-cycle rituals of everyday indigenous life, the missionaries attempted to reify these rites and their meanings so that they would appear to be normal and universal. The ultimate result was to make the Christian practices accessible through the native registers of common sense, thus giving them the appearance of being natural and ubiquitous, while freeing them of the need to justify themselves on other grounds. Of course, the sporadic public punishment of non-Indians that continued after 1547 reinforced this image of penitential discipline as general and uniform.

In effect, the domestication and normalization[45] of millions of unacculturated Indians by dozens of friars needed far more than an Inquisition. It called for a new regime of control that acted upon the soul to create self-disciplined colonial subjects. Unfortunately, an analysis of the methods used to effect this end, primarily through a penitential discipline founded on confessional practices, is beyond the scope of this volume, but it is taken up elsewhere.[46]

Bibliography

Alberro, Solange. "La Inquisición como institución normativa." In Seminario de historia de las mentalidades y religión en el México colonial , edited by Solange Alberro and Serge Gruzinski. Departamento de Investigaciones Históricas, Cuaderno de Trabajo 24. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1979.

———. La actividad del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición en Nueva España, 1571-1700 . Colección Científica, vol. 96. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1981.

Axtell, James. The Invasion Within; The Contest of Cultures in Colonial North America . New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Baudot, Georges. Utopía e historia en México: Los Primeros cronistas de la civilización mexicana (1520-1569). Translated by Vicente González Loscertales. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1983.

Behar, Ruth. "Sex and Sin, Witchcraft and the Devil in Late-Colonial Mexico." American Ethnologist 14 (1987): 34-54.

Cortés, Hernán. Cartas y documentos. Introduction by Mario Hernández Sánchez-Barba. Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa, 1963.

Cuevas, Mariano. Historia de la iglesia en México. 4th ed. 5 vols. Mexico City: Ediciones Cervantes, 1942.

Doctrina cristiana en lengua española y mexicana por los religiosos de la orden de Santo Domingo. 1548. Reprint. Madrid: Ediciones Cultura Hispánica, 1944.

Fabian, Johannes. Language and Colonial Power. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

García Icazbalceta, Joaquín. Don Fray Juan de Zumárraga: Primer Obispo y Arzobispo

de México. Edited by Rafael Aguayo Spencer and Antonio Castro Leal. 4 vols. Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa, 1947.

Gibson, Charles. The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule: A History of the Indians of the Valley of Mexico, 1519-1810. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1964.

———. Tlaxcala in the Sixteenth Century. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1967.

———. "Indian Societies Under Spanish Rule." In Colonial Spanish America . Edited by Leslie Bethell. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

González Obregón, Luis, ed. Proceso inquisitorial del cacique de Tetzcoco. Mexico City: Archivo General y Público de la Nación, 1910.

———. Procesos de indios idólatras y hechiceros. Mexico City: Archivo General de la Nación, 1912.

Greenleaf, Richard E. Zumárraga and the Mexican Inquisition, 1536-1543. Washington, D.C.: Academy of American Franciscan History, 1961.

———. "The Inquisition and the Indians of New Spain: A Study in Jurisdictional Confusion." The Americas 22 (1965): 138-166.

———. The Mexican Inquisition of the Sixteenth Century. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1969.

Hanke, Lewis. The Spanish Struggle for Justice in the Conquest of America. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1965.

———. Aristotle and the American Indians: A Study in Race Prejudice in the Modern World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1970.

Klor de Alva, J. Jorge. "Martín Ocelotl: Clandestine Cult Leader." In Struggle and Survival in Colonial America . Edited by David G. Sweet and Gary B. Nash. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1981.

———. "Spiritual Conflict and Accommodation in New Spain: Toward a Typology of Aztec Responses to Christianity." In The Inca and Aztec States, 1400-1800: Anthropology and History . Edited by George A. Collier, Renato I. Rosaldo, and John D. Wirth. New York: Academic Press, 1982.

———. "Sahagún and the Birth of Modern Ethnography: Representing, Confessing, and Inscribing the Native Other." In The Work of Bernardino de Sahagún: Pioneer Ethnographer of Sixteenth-Century Aztec Mexico . Edited by J. Jorge Klor de Alva, H. B. Nicholson, and Eloise Quiñónes Keber. Vol. 2 of Studies on Culture and Society. Albany: Institute for Mesoamerican Studies. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1988.

———. "Sin and Confession among the Colonial Nahuas: The Confessional as a Tool for Domination." In Ciudad y campo en la historia de México . Edited by Richard Sánchez, Eric Van Young, and Gisela von Wobeser. 2 vols. Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1990.

———. "Contar vidas: La autobiografía confesional y la reconstrucción del ser nahua." Arbor 515-516 (1988): 49-78.

Las Casas, Bartolomé de. Del único modo de atraer a todos los pueblos a la verdadera religión. Edited by Agustín Millares Carlo. Translated from the Latin by Atenógenes Santamaría. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1942.

Molina, Alonso de. Confesionario mayor en la lengua mexicana y castellana. 1569. Reprint, with introduction by Roberto Moreno. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1984.

Motolinía, Toribio de Benavente. Memoriales: o, Libro de las cosas de Nueva España y de los naturales de ella. Edited by Edmundo O'Gorman. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1971.

———. Historia de los indios de la Nueva España. Edited by Edmundo O'Gorman. Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa, 1973.

Taussig, Michael. Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Tentler, Thomas N. Sin and Confession on the Eve of the Reformation. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1977.