Contrasts in Influence: The Case of Marine Terminals

Historically, as emphasized in Chapter Two, the Port of New York—withits piers, docks, and related facilities for ocean-borne commerce—has been a central element in the settlement and economic development of the

New York region.[29] Despite the massive growth of economic activities that do not depend on ocean transport, the port has maintained an important role in the region's economy, with more than 170,000 of the region's jobs in 1978 directly involved in port-related activities.

Much of the port's 750 miles of waterfront is privately owned, but New York City, Newark, and other waterfront cities have long had city-owned port facilities, with ownership motivated both by hopes of generating income directly for the city, and by the perception that thriving city-sponsored port activities will encourage private industries that rely on ocean transport to locate and expand in their municipalities. Luther Gulick captured the significance of this latter potential in a 1947 essay, noting that a public agency "has the power to determine whether a community as a whole will expand as a raw material center or as a manufacturing center by the priority it gives to port facilities, loading and unloading equipment, wharfage rates, and rail and road connections."[30]

Alas, such hopes of city-government entrepreneurship are often disappointed. The city of Newark, for example, officially launched "Port Newark" in 1915 and began dredging its marshland to attract "great argosies of commerce . . . carrying the world's goods to Newark and Newark's wares to all points of the earth."[31] The marsh was partially dredged, some port facilities were begun, and a few industrial firms were attracted to the area. But because of the disruption of two wars—when the port area was in military hands—and the Great Depression, combined with a lack of adequate capital funds, Port Newark was only partly completed by 1946. Moreover, its buildings and piers needed rehabilitation and modernizing; and thirty years of effort, far from generating revenue for the city, had drained $10 million from city coffers.

The basic problem, as viewed by Newark city officials and business leaders, was the city's inability to allocate sufficient funds and managerial talent to develop the port area into a source of major economic benefit. "Forced to spread its limited resources on such projects as housing, schools and other civic improvements," Newark "could not spare capital funds to improve the waterfront. . . . "[32] By 1947 the city fathers had agreed to lease the seaport (and Newark airport as well) to the Port Authority, which would modernize and expand Port Newark. Using its growing bridge and tunnel revenues, the authority moved quickly—spending more than $3 million on rehabilitation and development in the first year, purchasing or leasing an additional 100 acres for expansion, and using its international promotion skills to bring added ocean freight traffic to the port.

By 1955 the Port Authority had invested more than $22 million in Port Newark, cargo handled at the port had expanded steadily, and the authority announced plans to create a new marine terminal adjacent to Port Newark, in

[29] See Vernon, Metropolis 1985, Chapter 2, and Benjamin Chinitz, Freight and the Metropolis (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1960), Chapter 1 and passim .

[30] Luther Gulick, "Authorities and How to Use Them," The Tax Review (November 1947), p. 50. Gulick's essay refers primarily to the potential of port authorities, and in fact his article was drafted during the period in which the Port Authority was negotiating for control of New York's port facilities. The argument applies, of course, to any government agency with control over terminals and related port facilities.

[31] A Newark newspaper article, circa October 1915, as quoted in Port Authority, "Port Newark," mimeographed, October 1965, pp. 2–3.

[32] Ibid., p. 6.

Elizabeth. Then, working closely with private transport operators and using a highly skilled staff, the authority laid out plans, continued to modify them as dredging was carried out and as technology for marine terminals rapidly altered, and in 1962 opened the new facility, a prototype for container terminals worldwide.[33]

By 1965, the Port Authority's investment in Port Newark exceeded $86 million, and its deepwater berths had more than doubled compared with the old city-owned terminal. In 1947, its last year of city operation, Port Newark had handled only 450 vessels and 800,000 tons of cargo, with 1,500 workers. In 1965, 1,500 ships berthed at Newark, and four million tons were handled by 4,500 workers. Port Elizabeth, in the midst of a $150 million construction program, added another 2 million tons of cargo, and dramatic additional growth was expected at the adjoining terminals during the next decade. As to the impact of these developments on the region, it was estimated that each ship generated $100,000 in direct business for companies in marine and international trade, with additional benefits to banking, wholesaling, and insurance industries.[34]

Compared with the expansion and vitality of the Newark-area marine terminals, the evolution of port facilities owned by New York City during these first two postwar decades was negligible. In 1947 Mayor William O'Dwyer, with unseemly foresight, had perceived the difficulty that City Hall would face in attempting to rehabilitate its 130 piers and miles of other waterfront facilities. "The City is now faced with making capital improvements for hospitals, schools and its transit facilities, which will tax its present power to raise funds," O'Dwyer explained in a letter to the Port Authority in October 1947. Since other demands prevented scarce city funds from being used to meet port needs, the mayor asked the bistate agency to consider whether it might redevelop city-owned terminal areas.

The Port Authority responded quickly and enthusiastically, urging that New York City join with Newark to permit the development of the port's marine facilities "on a truly regional basis"—under Port Authority management. By February 1948 the Port Authority presented a detailed proposal, involving expenditure of $114 million of authority funds for new piers, rehabilitation of existing structures, and other improvements. In addition, the port agency would make payments of $5 to $6 million per year to New York City during a fifty-year lease period.[35]

[33] On the development of Port Newark and Port Elizabeth by the Port Authority, see Port Authority, Twenty-Sixth Annual Report: 1946 (New York: November 1, 1947), pp. 7–10; Port Authority, Twenty-Eighth Annual Report: 1948 (New York: April 15, 1949), pp. 45–51; Port Authority, 1955 Annual Report (New York: n.d., ca March 1956), pp. 7–11; Port Authority, Annual Report: 1963 (New York: n.d., ca March 1964), pp. 8–13; John T. Cunningham, "Port Elizabeth: The Reshaping of Shipping," New Jersey Business, March 1970, pp. 31–35, 65.

[34] See Port Authority, "Port Newark," October 1965, pp. 1, 7–10; Chinitz, Freight and the Metropolis, Chapter 3; "A Showcase for Integrated Transport," Business Week, November 27, 1971 (reprint, 3 pp.). By 1978, the Port Authority's New Jersey marine terminals, which include Hoboken as well as Newark and Elizabeth, handled 2,100 ships and 10 million long tons of cargo; the three terminals employed 6,300 persons.

[35] The O'Dwyer-Port Authority exchange of letters and the authority's plan are included in Port Authority, Twenty Seventh Annual Report: 1947 (New York: November 1, 1948), pp. 35–36; Port Authority, Twenty Eighth Annual Report: 1948, pp. 54–68.

Having just seen its two great airports slip from its grasp into the embracing arms of what some city leaders saw as the port octopus, New York's Board of Estimate was not eager to lose control of its piers and docks as well. And the politically influential labor unions controlling the docks urged that the offer be rejected. Moreover, the city's Department of Marine and Aviation, hoping for at least half a future, said it could do the job for half the cost. So the Board of Estimate turned a deaf ear to the pleas of the mayor and civic associations in the city, rejected the Authority plan, and urged its own agency to go forward with a $55 million program.[36]

Unfortunately, with two-thirds of the city's piers more than forty years old, and half in poor condition, $55 million was insufficient; and the Board of Estimate failed to provide the Department of Marine and Aviation even that modest amount.[37] So the piers rotted away and floated out to sea, along with the city's hopes for economic revitalization of its waterfront.

By the mid-1960s, city officials concluded that something had gone wrong. "The expansion of modern cargo-handling facilities in Port Newark and Port Elizabeth," the City Planning Commission asserted in 1964, "have made serious inroads into the economy of the New York City sectors of the Port." The commission urged the city to develop a more vigorous "port development policy" in order to "preserve its economic stability and job base." Pressed by short-run problems in schools, subways, and sanitation, City Hall responded in its usual fashion, and two years later the planners lamented: "Our side of the harbor has no counterpart to the new, modern facilities which are attracting containership operations to Port Elizabeth."[38]

Now the cause of the "obsolescence of our port facilities" was, in the Planning Commission's view, readily found; it lay in the Port Authority's failure to "balance" its terminal developments in New Jersey with an equal share in New York. The Planning Commission therefore urged the city to press ahead—although just how, was less clear. The commission warned that constitutional limitations and existing budgetary commitments "caution against" the city's assuming any major new capital programs. Yet, in considering whether the Port Authority should take on a major role, the commission argued that the mayor would have to weigh the "long-range gains to the City's prestige and economy" against the "surrender of City land and its earned revenues" to the bistate agency.[39]

[36] The actions of the city are summarized in Port Authority, Twenty Eighth Annual Report, pp. 56–57. After the authority's proposal was rejected, Mayor O'Dwyer urged the authority to submit a second, more modest plan. Its 1949 proposal for $91 million in expenditures was also turned down by the Board of Estimate. See Port Authority, Twenty Ninth Annual Report: 1949 (New York: July 15, 1950), pp. 70–71.

[37] While the Port Authority plan had called for it to spend $114 million by 1960, and the city department had urged $55 million, the actual expenditures by the city as of 1960 were only $30 million. A student of the port's economy pointed out, however, that "current plans" called for additional expenditures of $200 million. Noting that these plans "must compete with other City needs" for limited funds, he concluded with admirable restraint: "One cannot readily assume that this program will be realized as rapidly as planned. . . . " Chinitz, Freight and the Metropolis, p. 82.

[38] City Planning Commission, City of New York, "The World Trade Center: An Evaluation" (New York, March 1966), p. 48. The 1964 statement in the text is from the Commission's report, "The Port of New York" (September 1964), as quoted in ibid., p. 46.

[39] Ibid., pp. 48–50, quoting in part from commission reports issued in 1964 and 1965. Despite the city's rejection of a major Port Authority program in the 1940s, by the mid-1960s theagency had three terminal projects on the New York side of the harbor, though none was on the scale of Port Newark-Port Elizabeth. The three were the Brooklyn-Port Authority Marine Terminal, Erie Basin-Port Authority Marine Terminal, and the Columbia Street Pier.

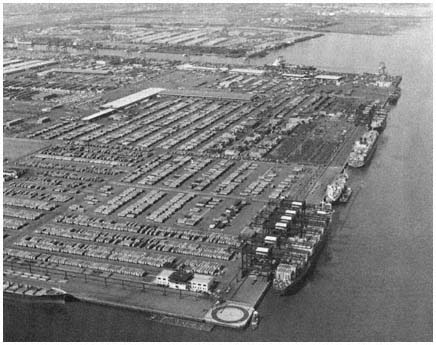

An important factor in maintaining the region's

economic vitality has been the modern port facilities

developed by the Port Authority in

Elizabeth and Newark.

Credit: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

As part of the Lindsay administration's negotiations on construction of the World Trade Center, Deputy Mayor Robert Price picked up this broken lance in 1966, making a series of demands for immediate Port Authority commitments, totalling about $230 million, to improve city marine facilities.[40] Price also attacked plans for additional investment by the authority in New Jersey terminals as "another example of the Authority's discrimination against our side of the harbor," and complained that "meanwhile, the New York side continues to deteriorate, and to lose business, jobs and much-needed new construction."[41]

[40] Once the World Trade Center had been approved by the two states, the authority needed permission from the city to close streets so that construction could proceed. Lindsay and his staff initially refused permission, and put forward a number of proposals for Port Authority assistance to the city. These are set forth in the letter from Robert Price to Austin Tobin, May 27, 1966 (17 p.). The marine projects included a new passenger ship terminal ($100 million), a containership terminal in Brooklyn ($80 million), additional development in South Brooklyn ($15 million), a new containership terminal, probably on Staten Island ($30 to $40 million), and removal of old Manhattan piers ($3 million).

[41] Quoted in Edith Evans Asbury, "Port Agency Scored on Jersey Project," New York Times, July 17, 1966.

Not much came of this foray. One project already under negotiation, a $40 million passenger ship terminal, was built and years later, in 1974, a joint agreement provided for authority construction of a $33 million container terminal in Brooklyn. At the end of the 1970s the authority's facilities in New Jersey were handling 10 million long tons, seven times the cargo passing through its New York terminals. The city department, now renamed Ports and Terminals, still controlled large numbers of piers and other waterfront facilities. A few of these piers had been rehabilitated, and in the city's 1980 budget the department noted that it was "planning several major projects, including the development of marinas and floating restaurants."[42] But perhaps the time for major terminal construction projects had passed;[43] and in any event it seemed likely, given New York City's budgetary constraints, that the City would have great difficulty simply keeping its aging piers in good repair while putting a few restaurants out in the harbor, under the haughty gaze of the World Trade Center.