Ramona Olazábal, the Girl with the Bleeding Hands

Ramona Olazábal was fifteen when she had her first vision on July 16 at Ezkioga. Born and raised on an isolated farm in Beizama, about twenty kilometers away, she was one of nine surviving children. Before the visions she stood out for her vivacity and her fine dancing more than her piety. At age nine she had gone to live with her sister in Hernani, and by age thirteen she was working in aristocratic households in San Sebastián. When she began to have visions in July 1931 she had spent much time away from the farm and had had some contact with the upper classes.[23]

R 8 gives Ramona's birthdate as 13 August 1915; PV, 18 October 1931, p. 5; Juan de Urumea, El Nervión, 22 October 1931; R 11.

Like other visionaries in July, Ramona wanted to know if there would be a miracle and when it would be. By the end of the month, she was "one of the best known seers," for newspapers had reported nine of her visions. At the beginning of September a Catalan pilgrim wrote that "her prayer consists of an insistent clamor for pardon and mercy for everyone" and that of the seers she was "the only one who sees the Virgin as happy."[24]

All 1931: LC, 17 July, p. 2; ED, 18 July, p. 12; and 31 July, p. 7. Also reports in ED, 24 and 26 July, and PV, 24 July. Delás, CC, 20 September 1931.

About this time Ramona stopped working and moved to Zumarraga, closer to the vision site. There she stayed with her cousin Juan Bautista Otaegui, one of Amundarain's curates, who boarded in the house of Amundarain's brother. She had many followers and for some she provided special messages. Amundarain's niece, the Aliada Teresa, often accompanied Ramona shopping, for Ramona had money from believers. Ramona gave a sealed letter to Otaegui saying that on October 15 the Virgin would give her a rosary. Amundarain took the prediction seriously, no doubt because it coincided with the visions of the San Sebastián Aliada. Ramona sent a similar letter to a prominent family in San Sebastián. And on October 13 and 14 she told many people to bring handkerchiefs, for the Virgin was going to wound her.[25]

On Ramona's shopping see Juan María Amundarain, San Sebastián, 3 June 1984, p. 3. Otaegui was certain the miracle would occur, according to Pío Montoya, San Sebastián, 7 April 1983; B 212. Ramona informed the San Sebastián family of Luis Zulueta, a Republican deputy in the Cortes on good terms with Múgica and Echeguren: LC, 17 October 1931, p. 2, and 17 May 1932, p. 1.

On October 14 Amundarain wrote to the Aliada leader María Ozores in Vitoria: "It seems the Virgin is calling you here; we are in historic days, and we have to give heaven strength." He assigned Ozores and another Aliada to stay with Ramona the next day and search her before she went up the hill. Amundarain had a family lunch to celebrate the saint's day of his mother, and then he, his brother, and his nephew went to the apparition site.[26]

Amundarain to Ozores, Zumarraga, 14 October 1931, AAJM; one of the Aliadas, María Angeles Montoya, San Sebastián, 28 April 1984, p. 7, who was with Dolores Ayestarán, the sister of a priest who worked with Amundarain; for family lunch: Juan María Amundarain, San Sebastián, 3 June 1984, p. 4.

After the Aliadas searched her, Ramona went into an outhouse before going up the hillside. Fifteen to twenty thousand persons, the largest crowd since July 18, had been attracted by the predictions she and Patxi Goicoechea had made about a miracle. Ramona emerged at about 5:15 P.M. with her close friend, a girl from Ataun who was also a seer. When Ramona neared the fenced area for visionaries, she lifted her hands. Blood spurted from the backs of both. "Odola! Odola! [Blood! Blood!]" shouted the crowd. Men carried Ramona into the enclosure, and there a doctor found a rosary twisted around the belt of her dress. In an atmosphere of awe and anguish men carried her downhill seated in a chair, like an image in a procession. All the time people collected her blood on their handkerchiefs. Alerted by phone, pilgrims poured in from all over the Basque Country well into the night.[27]

R 17-18; L 13. See SC E 83-94 for eyewitness. News on 16 October 1931 in PV (San Sebastián), PV (Bilbao), DN, Easo, and LC, and on 17 October 1931 in PV, VN; for excitement that night: Casilda Arcelus, Ormaiztegi, 9 September 1983, p. 3.

The Aliadas Amundarain had detailed to observe Ramona were totally convinced. When María Angeles Montoya arrived at her home in Alegia, she told her brother Pío that a miracle had happened. Pío, a priest who was cofounder of El Día , immediately called Justo de Echeguren, the vicar general of the diocese and an intimate family friend. Pío emphasized that unless Echeguren investigated Ramona's wounding at once there would be no stopping the matter.[28]

For Echeguren's involvement: Pío Montoya, San Sebastián, 7 April 1983, pp. 4-8.

The next morning Echeguren arrived by train at Zumarraga, where he met Montoya, Amundarain, and Julián Ayestarán, a priest who worked with Amundarain on the Aliadas and whose sister had watched Ramona the day before. Amundarain reported what had happened and spoke favorably about the innocence of the original seers. Echeguren was skeptical about the miracle, but the fact that María Angeles Montoya, who was like a niece to him, believed in it gave him pause. So he immediately formed an ecclesiastical tribunal consisting of himself, Montoya, and Ayestarán to interview witnesses.[29]

Montoya's detailed recollection of the hearing coincides with what Echeguren wrote José Antonio Laburu, Vitoria, 13 April 1932.

Before starting the proceedings, Echeguren had in hand the letter that Ramona had given her cousin Otaegui. He also talked to a man whom Ramona had told to bring a handkerchief and to her friend from Ataun, whom Ramona had told she would receive stigmata. He then asked Ramona whether she had told anyone about what would happen. She denied three times that she told anyone, and Echeguren became so angry that he broke his pencil. He confronted her with the conflicting evidence, including the letter, and she admitted that she had indeed told people and named still others. He told her she had been lying and sent her off.

Crowd at Ezkioga, mid-October 1931

At that point a man from Lezo asked to speak to Echeguren in private. He said that the day before he had been next to Ramona when, stunned by seeing the blood coming out of her hands, he had lowered his eyes in awe and seen to his surprise a razor blade on the ground. He had come back to look for it. To settle the matter, Echeguren asked Montoya to find two doctors, one Catholic and the other, if possible, a non-Catholic, to examine Ramona's wounds. Montoya called in Doroteo Ciaurruz, later the Basque Nationalist mayor of Tolosa, and Luis Azcue from the same city and both examined Ramona that afternoon. That night they reported to Echeguren at Montoya's house that they thought Ramona had inflicted the wounds on herself, most probably with a razor blade. Echeguren immediately drew up a note for the press that said there was positive evidence of natural, not supernatural, causes for Ramona's wounds.

At some time in the fall of 1931 Echeguren instructed priests not to lead the rosary at the site and, according to one source, reprimanded Amundarain for his involvement in the apparitions. On November 4 Amundarain sadly wrote to María Ozores:

Ezquioga continues to wind down. New prophecies of something extraordinary, new dates, new preparations, new failures. I continue to believe in a

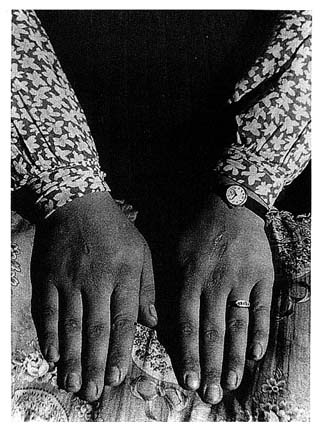

Scars on Ramona Olazábal's hands, late October 1931.

Photo by Raymond de Rigné, all rights reserved

powerful, extraordinary intervention and presence in these mountains of Our Mother, but among the seers there is a lot to be purged.[30]

Amundarain to Ozores, Zumarraga, 4 November 1931, AAJM.

I find no more reports of Amundarain at Ezkioga. But he continued to hear the effects of the visions in the confessional. On December 14 a group of Catalan believers visited him. One of them wrote:

The parish priest of Zumárraga spoke to us of the beautiful spiritual fruit harvested at Ezquioga. There have been countless general confessions, he told us, and they still continue. Even today, he added, there were some in this church. Even men eighty years old have wanted to make a general confession.

He said he believed 80 percent of the seers, but that Freemasons had become involved to discredit the apparitions. By this time both he and Otaegui had broken with Ramona.[31]

Gratacós, "Lo de Esquioga," 14-16. ARB 9-10 also mentions the visit. Suspicion of Freemason plots to make the church look ridiculous may derive from the Leo Taxil affair, in which an anticlerical freethinker feigned conversion to Catholicism, got church leaders to believe preposterous stories, and then revealed the hoax (Ferrer Benimeli, El Contubernio).

A year later, on 16 December 1932, due to stress and ill health, Amundarain resigned as parish priest to devote himself fully to the Alianza, which he did for

the rest of his life. But he did not renounce his hopes for Marian apparitions or his hopes for the role the Aliadas would play. In his copy of a book of prophecies published in 1932, the following passage from the prophecy of Madeleine Porsat is underlined and "¿Alianza?" written in the margin:

The church is preparing everything for the glorious coming of Mary…. It forms a guard of honor to go out and meet the angels that come with her.

The arch of triumph has been erected. The hour is not distant.

It is she herself in person, but she has her precursors, holy women and apostles, who will heal the wounds of the body and the sins of the heart.[32]

Sobrino, Amundarain, 93-94. Echeverría Larrain, Predicciones, 62. Amundarain loaned his copy to a fellow priest, Juan Ayerbe, whose niece kindly showed it to me. See also below, chap. 14, "The End of the World."

Antonio Amundarain was prudent in public about the visions. As far as I know, he had little personal contact with the seers, but his sharp attention, foresight, and careful use of the media were critical to the pace and momentum of the visions. Many people thought he was acting on behalf of the diocese. El Pueblo Vasco reported that "it was [Amundarain] who was charged by Vitoria to gather testimony of the events." If this was the case, Amundarain's role would have been unofficial. Such a procedure was not unusual. Both at Limpias and at Piedramillera bishops instructed the parish priests to take down testimony of seers as if at their own initiative. When Amundarain issued the note on July 28 referring to the commission of priests and doctors as "official," the vicar general immediately issued a denial, disavowing any diocesan connection. Given the vicar general's subsequent total skepticism, it would seem that Amundarain was on thin ice from the start. But at least in some matters he seems to have worked for Echeguren. That Amundarain had matters in hand probably contributed to the diocese's relaxed attitude in the first months.[33]

EZ and PV of 18 July 1931; Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 52, 126; ED and PV, 29 July 1931; Echeguren wrote to Rigné, 22 December 1932 (typed copy in private archive), that it was on his instructions that the Aliadas watched Ramona on the day of the miracle. Amundarain may have told him about Ramona's letter, and he must have let Amundarain choose the women.