Seven

"A Kind of Majesty"

The Postbellum Architecture of Victorian Yoknapatawpha

Following the Civil War, most of the antebellum architectural styles continued to be built sporadically on into the twentieth century, but there was at the same time a marked change of mood. In the South, for a while, there was a poverty-stricken aura of defeatism, inaction, and decay. In the booming, industrial North, there was, by contrast, a new sense of energy, prosperity, posturing, and self-indulgence. Sociologist Thorstein Veblen embalmed the zeitgeist with his memorable phrase "conspicuous consumption." Historian Vernon Louis Parrington stressed another aspect of the era's spirit by calling it "the Great Barbecue." Eventually the "New South," following Reconstruction, would struggle wanly onto the national bandwagon, whistling bravely and building with strained exuberance.

The fashionable "new" architecture of the postwar period was a much encumbered extension of the two major antebellum styles—the neoclassical and the neo-Gothic. The expression of the former, developed largely in France, was a highly strung revival of the seventeenth-century French Baroque, with its mansard roofs and rounded, oval, and curving forms, a revival that was patronized by Emperor Napoleon III and his architect, Baron Georges Haussmann. In the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s, much of Paris was rebuilt in this style atop a newly reopened city of grand diagonal avenues that were superimposed upon what remained of the meandering medieval streetscape. Because of the "imperial" patronage, the style was called "Second Empire" or, more informally, "Mansardic." The most prominent Second Empire buildings in America were

Alfred B. Mullett's State, War, and Navy Building (1871-75), conspicuously sited just west of the White House; Smithmeyer and Pelz's Library of Congress (1886-97), conspicuously nestled just east of the Capitol; and John McArthur's Philadelphia City Hall, conspicuously monopolizing the central square of William Penn's sternly orthogonal city plan of 1681.

The other side of the postbellum architectural coin was the High Victorian Gothic, made especially popular in the mid-century English architecture of William Butterfield. As opposed to the monochromatic, rounded, mansardic flourishes of the Second Empire, the High Victorian Gothic emphasized pointed, spiky, polychromatic, attenuated versions of Downing and Upjohn's relatively gentle antebellum Gothic Revival. In the north, the most revered and noticed version of this inspired concoction was Ware and Van Brunt's Memorial Hall at Harvard (1871-88), a monument to the Harvard men who had perished for the Union in the Civil War. The Harvard men who had died for the Confederacy received no mention in Ware and Van Brunt's monument. The English savant, John Ruskin, called it the finest building in America. In addition to the two dominant styles, moreover, was a third category of even more exotic variations on, or combinations of, the Mansardic and the High Victorian. This latter potpourri, usually defying classification, was summed up by the phrase: "Too much is not enough."

A relatively pure Oxford example of the Second Empire Mansardic was the Roberts-Neilson House (ca. 1870), conspicuously sited on the town's elegant South Lamar Street (Fig. 65). Above its generous, one-storey front portico ran the handsomely polychromed and densely dormered Mansard roof. A Swedish immigrant designer/craftsman, G.M. Torgerson (1840-1902), who worked on numerous postbellum Oxford buildings, designed the house in the chic new style for the merchant Charles Roberts, who passed the house on to his daughter as he himself acquired the Pegues house and named it "Edgecombe." One door south of the Roberts House rose the kindred Stowers-Longest House (ca. 1895; Fig. 66), a hybrid combination of Victorian modes that imbibed strong doses of the spiky, blocky Eastlake style, an ambience evoked by the English architect Charles Eastlake in his Hints on Household Taste (1868), popularized in an American edition of 1872. [1]

A spirited amalgam of Victorian styles coalesced in the splendid and sprightly High Victorian Gothic house for the banker W.L. Archibald on University Avenue at Fifth Street (ca. 1876), with rich interior detailing by Torgerson, who may have designed the entire structure. Later acquired by businessman Peyton Skipwith, the house became for the next half century the domain of his daughter, the redoubtable Kate Skipwith. Blithely demolished by the University in 1974, two years short of its centen-

Figure 65

Roberts-Neilson House, Oxford, Mississippi,

attributed to G. M. Torgerson, architect (ca. 1870).

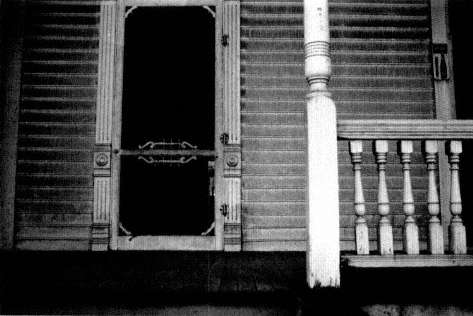

Figure 66

Stowers-Longest House (Roberts-Neilson House

in background), Oxford, Mississippi (ca. 1895).

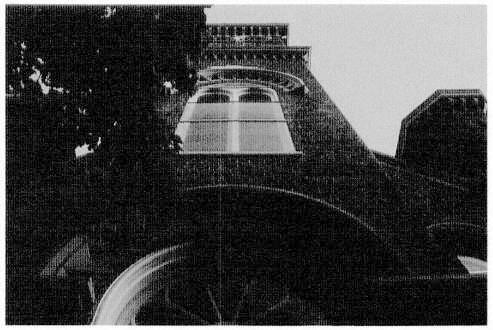

Figure 67

Smith House, Holly Springs, Mississippi (ca. 1900).

nial, it was a reigning presence on the Oxford landscape throughout William Faulkner's life. The style continued to appear through the turn of the century, as in the Smith House, Holly Springs (ca. 1900), an exuberant wedding cake of a structure, which in its well-maintained vigor would become more appreciated as its years increased (Fig. 67). [2]

A more sedate version of the style, in Como, Mississippi, had a particularly poignant and ironic history. In 1893, Obedience Pointer Taylor, wife of the planter and cotton broker Robert Taylor, inherited the fabled "Heaven Trees" house of her grandfather, Dr. George Tait (Fig. 46). By the 1890s, the triple-porticoed house, immortalized in Stark Young's fiction, was in bad repair and, besides, was not to Bedie Taylor's taste. She felt no call to preserve the antebellum architecture that had preceded the "Lost Cause." She considered herself a modern woman and therefore wanted what by 1890s standards could be considered a modern house. For this she turned to the best local architect, Anders Johnssen, who, like G. M. Torgerson of Oxford, was a Swedish immigrant and an accomplished designer-craftsman. With innocent good intentions, he had anglicized his name to Andrew Johnson, a moniker that could not have been a popular one in postbellum Mississippi. Nevertheless, he had built a series of stunning residences, churches, and public structures throughout Panola County.

Since the new house for Bedie and Robert Taylor would be placed relatively close to the major street in the booming village of Como, it would not actually threaten the older Tait house, which sat farther back on the property. But there seemed no need to keep them both, and Mrs. Taylor ordered the house of her ancestor demolished. The workmen who were hired to accomplish this, however, reminded her that the lumber from the Tait house was far too rare and fine to be discarded and that it would be both frugal and appropriate to use it in the construction of the new house. Hence the materials of the old Tait mansion were literally transplanted in 1893 to the Victorian Taylor house (Fig. 68). In the early 1940s, the youngest Taylor son married and built a sturdy brick house next door, while his two bachelor brothers lived until their deaths in the decaying Taylor House with its—by now also decaying—"Heaven Trees" lumber. In the 1970s, as the work of its architect, Andrew Johnson, became better appreciated, the house was placed on the National Register of Historic Places and was subsequently restored. Though Faulkner most likely knew little, if any, of this story, it was a social and architectural saga worthy of his richest imaginings. [3]

An equally prominent remodeled Oxford structure that Faulkner knew through family connections was the residence known as "Memory House," the home of his brother john Faulkner. Though first built as a two-storey neoclassical mansion in the

Figure 68

Robert Taylor House, Como, Mississippi, Andrew Johnson, architect (1893).

Figure 69

Memory House, home of John W.T. Faulkner III, Oxford, Mississippi (ca. 1855 and later).

1850s by the planter Paul Barringer, it passed through several owners in the mid-nineteenth century, including Judge Duke Kimbrough, who in the 1880s removed the Greek Revival portico and replaced it with a Victorian facade complete with a central tower (Fig. 69). In the early twentieth century, J. O. Ramey acquired the house, after which time his daughter, Lucille, infused it with a lively social life. W. C. Handy came down from Memphis to perform at dances there. In 1924, Lucille Ramey married John Fa[u]lkner, who, with their sons Jimmy and Chooky, would endow Memory House with warmth and activity. [4]

The ecclesiastical counterpart of such residential eclecticism was Oxford's handsome, brick First Presbyterian Church (1881), built on the site of the original frame structure, which had been reared in 1843. In 1864 Union troops torched the building, but an alert church member who lived nearby was able to extinguish the blaze. In the 1870s disagreement developed among differing factions in the congregation as to whether to renovate the old structure or construct a new one. The latter sentiment prevailed, and the new church was dedicated in 1881 (Fig. 70). No record survives to identify the designer or builder, though circumstantial evidence suggests that it could have been G. M. Torgerson, whose architectural presence in Victorian Oxford was comparable to the antebellum hegemony of William Turner's neoclassicism. [5]

The First Presbyterian was a rival to the nearby Cumberland Presbyterian Church, an antebellum neoclassical structure that was itself transformed in the 1880s by a neo-Gothic remodeling. In the First Presbyterian, twin towers of ambiguous stylistic origins flank the central tower and doorway, which leads into the austerely moving interior, a determinedly plain space in contrast to the exterior, embellished only by brilliant stained glass windows set within rounded, neo-Romanesque frames. Members of the congregation included Lemuel and Lida Oldham, the parents of Estelle Oldham Faulkner. The church was thus a structure that would have entered Faulkner's consciousness, not only as a prominent feature on the Oxford landscape, but as a building with personal, familial associations as well.

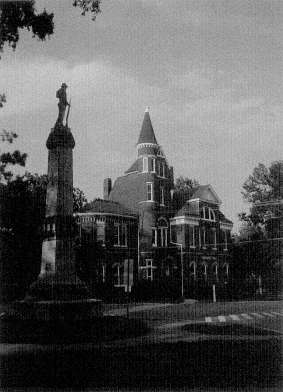

Another High Victorian building of the vaguely defined "Queen Anne" mode was the new University of Mississippi Library (1889), located on University Circle just north of the Confederate Monument (Fig. 71). An important building in Faulkner's intellectual development, he visited it often, especially as a youth when his family lived in a similar, late-Victorian campus residence nearby. Later, in the early 1920s, after the building had become the home of the Law School, young William Faulkner, pursuing odd jobs, traversed the structure as a part-time carpenter and painter. Still, the most imposing Victorian public building in Faulkner's Oxford was the Federal Court-

Figure 70

First Presbyterian Church, Oxford, Mississippi (1881).

house on the northeast corner of the Square (Plate 10). It was built in 1885 in the pervasively popular style of Richardsonian Romanesque, named after the Louisiana-born Boston master H. H. Richardson, whose strong, well-proportioned, free renderings of the medieval Romanesque caught the nation's attention in such monuments as Trinity Church, Boston (1872-77), the Allegheny County Courthouse, Pittsburgh (1884-88), and the Marshall Field Wholesale Store, Chicago (1885-87). Their progeny pervaded the American landscape, as in the Federal Courthouse at Oxford.

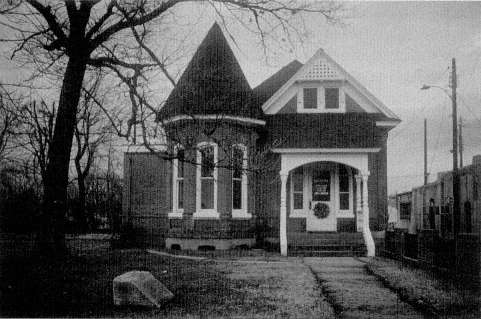

A related, smaller Victorian building that Faulkner knew well, just west of the Square, was the law office of his friend Phil Stone, built before the Civil War by the attorney William Sullivan. The Victorian tower at the front was added around the turn of the century (Fig. 72). Later Faulkner described a structure almost identical to it, though located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the Quentin section of The Sound and the Fury: We went down the street and turned into a bit of lawn, in which, set back from the street, stood a one-storey building of brick trimmed with white. We went up . . . to the door and entered a bare room smelling of stale tobacco .[6]

The most peculiar Mississippi Victorian pile to penetrate Faulkner's consciousness was not in Oxford but in Ripley—the home of his own great-grandfather, Colonel

Figure 71

Old Library (1889) and Confederate Monument (1906),

University of Mississippi, Oxford.

Figure 72

Law Office of Phil Stone, Oxford, Mississippi (1850s, 1890s).

William Clark Falkner. After Falkner's antebellum house was burned by Union troops in 1863, he lived, according to his biographer, in "a simple, trim, one-storey building, modeled in plain good taste." In 1884, however, he completely transformed that building with the addition of two large new storeys (Figs. 73, 74). The resulting "Italian Villa," as it was called in Ripley, reflected the title, the content, and the sources of his recent, and final, book, Rapid Ramblings in Europe (1884), a revision of travel letters he had written the year before to his friend and kinsman, Thomas Spight, editor of the Southern Sentinel who published them there. [7]

Falkner's newly enlarged house was inspired apparently by several villas and castles he had admired in Italy and France. Jammed on top of the original house, the new, slightly recessed, second floor sported four large gables, one on each side, containing French doors that opened to balconies decorated with ornate wrought-iron railings. Above this floor, in another recession, rose a large square room at the top, fenestrated with both rectangular and round porthole windows and crowned with a French Mansard roof topped by a "widow's walk." A contemporary notice in the Jackson Clarion asserted that Falkner "has built a residence that is quite palatial in style and proportions. Bel Haven excepted, there is no residence at the state capital that can compare with it." Ripley historian Andrew Brown, however, contrasted the exuberant facade with the plain, unexceptional interior: "The outward ostentation of the house, compared to its commonplace interior, makes one wonder if its building did not show that the Colonel's love of show was beginning to overrule his judgment." A later observer simply called the house an "architectural monster." [8]

Some of the house's furnishings echoed this judgment, particularly a stuffed alligator, caught in the Florida swamplands by the Colonel's daughter Effie and brought back to Memphis to be filled with sawdust by a taxidermist. Fixed to stand incongruously upright on its hind legs, the creature stood in the Falkners' front hall, with extended claws holding a large seashell intended to receive the calling cards of the Ripley gentry who called upon the Falkners (Fig. 75). Directly across the street, however, Falkner built a more felicitous and gracefully proportioned house as a wedding gift for his daughter, Willie Medora Falkner Carter (Fig. 102). Though William Faulkner knew his great-grandfather's house when he was a child in Ripley, and later when he visited there, he left no specific recollections of it and made no direct references to it in his work. He did leave a poignant record, however, of a childhood experience that occurred at his Aunt Willie's house across the street. (See Appendix, p. 141.) [9]

Figure 73

Falkner House, Ripley, Mississippi (1884).

Figure 74

Courthouse Square, Ripley, Mississippi, Falkner House in center distance (ca. 1920).

Figure 75

Stuffed Alligator from Falkner House, Ripley, Mississippi (ca. 1880s).

Faulkner did not admire postbellum Victorian Mississippi architecture, at least not in its residential forms. He used it in his work to symbolize the varied anxieties of the postwar New South, either as an example of parvenu social climbing or of resigned old guard resolution to accommodate the new order.

In Sartoris , a novel that is packed with architectural symbolism, Faulkner described a house built in Jefferson by an aspiring "hill-man" from the county, who had bought a beautifully planted lot in town and cut some of the trees in order to build his house near the street after the country fashion. . . . The lot had been the site of a fine old colonial house which stood among magnolias and oaks and flowering shrubs. But the house had burned, and some of the trees had been felled to make room for an architectural garbling so imposingly terrific as to possess a kind of majesty. It was a monument to the frugality (and the mausoleum of the social aspirations of his women) of a hill-man who had moved in from a small settlement called Frenchman's Bend and who, as Miss finny Du Pre put it, had built the handsomest house in Frenchman's Bend on the most beautiful lot in Jefferson. The hill-man had stuck it out for two years, during which his womenfolk sat on the veranda all morning in lace-trimmed "boudoir caps" and spent the afternoons in colored silk, riding about town in a rubber-tired surrey; then the hill-man sold his house to a newcomer to the town and took his women back to the country and doubtless set them to work again .[10]

Eventually, of course, these excessive Victorian concoctions became venerable monuments on the Mississippi landscape and occasionally, like their neoclassical neighbors, became myth-laden ruins. Faulkner's most famous evocation of such a condition occurred in his story "A Rose for Emily," where, as the Mississippi writer Elizabeth Spencer put it: a sweet little Southern lady, Miss Emily Grierson, poisoned her lover and "kept his corpse around as a playmate." Here, once again, as he did throughout his work, Faulkner used the style, setting, and condition of a building to evoke the condition of its inhabitants: It was a big, squarish frame house that had once been white, decorated with cupolas and spires and scrolled balconies in the heavily lightsome style of the seventies, set on what had once been our most select street. But garages and cotton gins had encroached and obliterated even the august names of that neighborhood; only Miss Emily's house was left, lifting its stubborn and coquettish decay above the cotton wagons and gasoline pumps—an eyesore among eyesores .[11]

Though Faulkner was uneasy with most Mississippi Victorian architecture, he had kind, and emotionally saturated, words for the Yoknapatawpha County jail, an important building in both Oxford's and Jefferson's history. Faulkner imagined the Jefferson jail to be older than the one in Oxford, which was actually built in 1871, possibly

Figure 76

Oxford Jail, Oxford, Mississippi (1871).

designed by Willis, Sloan, and Trigg, who designed the second courthouse, with similar decorative features, at approximately the same time (Pig. 76). In both Oxford and Jefferson, the jail retained an impressive presence on the landscape until it was needlessly demolished in the 1970s, just as it reached its centennial year. In Intruder in the Dust , Faulkner captured the essence of the actual, and the apocryphal, building in one of his most memorable paeans to the power and importance of architecture: It was of brick, square, proportioned , with columns across the front and even a brick cornice under the eaves because it was old, built in a time when people took time to build even jails with grace and care and he remembered how his uncle had said once that not courthouses nor even churches but jails were the true records of a county's, a community's history, since not only the cryptic forgotten initials and words and even phrases cries of defiance and indictment scratched into the walls but the very bricks and stones themselves held, not in solution but in suspension, intact and biding and potent and indestructible, the agonies and shames and griefs with which hearts long since unmarked and unremembered dust had strained and perhaps burst .[12]