PART ONE—

THE INQUISITION AND THE LIMITS OF DISCIPLINE

One—

Colonizing Souls: The Failure of the Indian Inquisition and the Rise of Penitential Discipline

J. Jorge Klor de Alva

When you tell someone your secret, your freedom is gone.

—FERNANDO DE ROJAS, La Celestina

On a November morning in 1539 don Carlos Ometochtzin, the native leader of the former city-state of Texcoco, was taken out of the prison of the Holy Office garbed in the typical sanbenito cloak and cone-shaped hat of the sentenced offender. He was paraded through the streets of downtown Mexico City, candle in hand, to a scaffold surrounded by the multitude that came to witness his sentencing and abjuration, and later to see his strangled body burn at the stake.[1] For the majority of the natives, it would be unfortunate that never again would an anti-Spanish rebel meet his end at such a public spectacle. In less than a decade, the stake where individual bodies were set ablaze was replaced by the local controls of provisors (or vicars-general) of the dioceses or archdioceses[2] and, even more important, by the confessional, its penances, its magical threats, and its very real capacity to command the submission of tens of thousands of wills to the nascent colonial structure. The two related processes alluded to by these events—the failure of the Indian Inquisition and the consequent rise of penitential discipline, whose control mechanisms played a leading role in the colonization of the Nahuas (the Aztecs and their linguistic and cultural neighbors)—are the subject of this essay.

From the beginning of the colonial effort in New Spain, ambivalence about the Holy Office limited its utility as an instrument for the domination of natives. For instance, the movement to exclude the Indians from the authority of the Inquisition reached an early climax in 1540, when the apostolic inquisitor, Fray Juan de Zumárraga, received a reprimand from Spain for imposing the death sentence on the cacique don Carlos.[3]

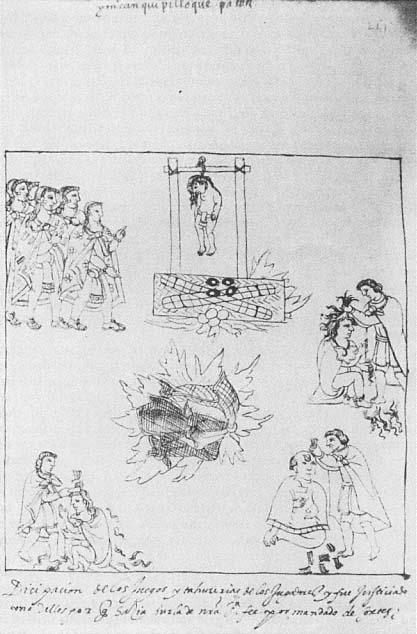

Fig. 1.

Two figures in penitential costume.

The Indians, however, continued to be processed by the Inquisition throughout the decade. And although official warnings to avoid treating the natives with severity were heard, no official prohibition against trying them outside the local dioceses or archdioceses was issued until 1571, when Philip II formally removed the Indians in the Spanish colonies from the jurisdiction of the Holy Office.[4] Despite a previous absence of legislation specifically excluding the Indians, some form of proscription nonetheless existed, because it appears that only one case involving Central Mexican Indians came before the Holy Office from 1547 to 1574.[5] Ambivalence is further suggested by the fact that out of 152 procesos acted upon between 1536 and 1543, the years of greatest inquisitorial

persecution of natives, only about nineteen involved Indians (see Table 1.1) and the number accused was quite small, approximately seventy-five.[6]

Given the seemingly endless possibilities—painfully brought home to us by the experiences of some contemporary nation-states—for forcing subordination through a "culture of terror,"[7] why were so few natives tried, tortured, or executed by the Inquisition? And why was colonial policy so inconsistent that the Indians ended up beyond its grip altogether, although no law demanded that that be the case until 1571, while the need for maximizing control was fully recognized as critical, by both Church and Crown, prior to this date? As is usually the case when spectacular forms of oppression give way to their more subtle varieties, the reasons commonly offered for the Spanish retreat from an aggressive application of such a powerful instrument for subjecting natives have centered on an assumed rising cry of humanitarian sentiment,[8] which is said by some[9] to have echoed the following orders issued in 1540 to the apostolic inquisitor, Archbishop Zumárraga:

since these people are newly converted . . . and in such a short time have not been able to learn well the things of our Christian religion, nor to be instructed in them as is fitting, and mindful that they are new plants, it is necessary that they should be attracted more with love than with rigor . . . and that they should not be treated roughly nor should one apply to them the rigor of the law . . . nor confiscate their property.[10]

But the implementation on humanitarian grounds of these instructions could not have been the primary force that led to the exemption that was generally observed. First of all, the Visitor General Francisco Tello de Sandoval, who replaced Zumárraga in New Spain in 1544 and was responsible for making known the New Laws of 1542—the laws that exhibited the greatest degree of toleration Charles V was able to muster on behalf of the Indians—not only was not instructed to avoid trying natives when acting as apostolic inquisitor but, on the contrary, during his three-year term failed to dismiss the cases against the Indians that came before the Holy Office.[11]

Second, although we know from the effects of the writings of Bartolomé de Las Casas and those of other reformers that this movement could have an influence on the formation of colonial policy,[12] the reform was focused on limited circles during the middle decades of the century and was more successful among Spanish rulers in the Old World than among colonial officials, who had to face the very real wrath of the settlers when they ventured arguments on behalf of the Indians. Fur-

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

thermore, in the New World much if not most of the legislation that favored the indigenes over Spanish interests was generally disregarded or selectively applied.[13] As a consequence, the disputes of the intellectuals, particularly those that took place in Spain,[14] had very limited practical significance in New Spain unless they reflected policy implications that supported the powerful sectors that ruled the colony. These facts point to the difficulties that undermine any categorical conclusion concerning the timing and role played by the toleration movement in the collapse of the Indian Inquisition. Thus, when it comes to measuring the relative strength of the forces that acted to remove the Indians through the Holy Office, it may be more profitable to pay attention to the everyday exigencies of colonial control than to the royal fiats or the juridical or theological arguments that sometimes informed them.

The Inquisition and the Economy of Punishment

Although its ostensible function was to safeguard the orthodoxy of the faith, the Holy Office was recognized to be and constantly was used as an important tool for social and political control since its founding in the thirteenth century.[15] In the New World the history of the Inquisition is primarily the story of the struggles over power and truth that marked the changing fortunes of the various ethnic, racial, and social sectors.[16] Following the defeat of the Mexicas of Mexico-Tenochtitlán in 1521, Cortés and the Franciscan friars put the Holy Office to work to secure their predominance over both upstart Spaniards and recalcitrant Indians. By the surprisingly early date of 1522 an Indian from Acolhuacán appears to have been formally accused of concubinage, thereby becoming the first person in Mexico to be tried by an agent of the Holy Office.[17] This presaged the use of inquisitorial punishment to regulate the behavior of Indians and Europeans that was generalized the following year, when two regulations were issued whose topics fit well into the hands of the Cortesian band. One edict, aimed at Europeans, opposed heretics and Jews; the other, whose vagueness was more a license to prosecute than a guide to proper behavior, was "against any person who through deed or word did anything that appeared to be sinful"![18]

In New Spain the regulatory possibilities of the latter ordinance were especially clear to those who interpreted the culture of the Nahuas as a satanic invention, and who used this as a justification for persecuting indigenous religious and sociocultural practices as criminal. Indeed, as the military and political hegemony of the Spaniards solidified, this popular interpretation was implemented as an apparatus of control by turning

Fig. 2.

"Discipline of players and gamblers and punishment of one who

had ridiculed our holy faith, by order of Cortés."

social customs and beliefs, acceptable in the native moral register, into sins, subject to temporal and symbolic punishment according to the Spanish criminal/canonical code. The tracing of both European and New World moralities onto the same penal map resolved the problem of cross-cultural (national) jurisdiction immediately. Thus, the Franciscan friar Martín de Valencia, who read into many aspects of the native cultures the authorship of the Devil, began to persecute recently baptized Indians in his capacity as commissary of the Holy Office immediately after his arrival in 1524. By 1527 his zeal was such that he had four Tlaxcalan leaders executed as idolaters and sacrificers,[19] even though the previous year the Franciscans had lost control of the Inquisition to the Dominicans.[20] In turn, the Dominican leaders of the Holy Office lost no time setting the institution to the task of stopping Cortés and his Franciscan allies from monopolizing the mechanisms of social and political domination; they sought to accomplish this power shift primarily by processing scores of their rivals as blasphemers.[21] However, with the arrival of the first viceroy in 1535, and the initiation of Zumárraga's episcopal tribunal the following year, the attention of the Holy Office shifted from the highly partisan contests between Spaniards[22] to the need to organize a colonial society primarily out of Nahuatl-speaking Indians.

It is hard to imagine a more difficult project: political and religious resistance, demographic ratios, language barriers, cultural distances, and extensive geographic spaces stood in the way, and the Spaniards had few precedents they could follow with confidence. Neither the confrontations with heretics, apostates, or non-Christians back home, nor their experiences with the far less socially integrated tribal and chiefdom communities in the circum-Caribbean area, prepared the Spaniards for the encounter with the city-state polities of New Spain. In Central Mexico cultural, regulatory, and security concerns contrasted sharply with those faced in Spain; there, not only did a variety of effective mechanisms of social control exist that could not be duplicated in the New World, but the problems of ethnic diversity in the peninsula tended primarily to affect civic unity rather than to challenge political stability or cultural viability, as was frequently the case in Mexico.

Consequently, from the time of the fall of Tenochtitlán, the primary requirement for the establishment of a colony was tactical and ethnographic knowledge, which called for the development of new disciplinary and intelligence techniques.[23] To gain control, the Spaniards needed information about the topography and natural resources of the land, the

political and social organizations and their jurisdictions, the geography of economic production, the type and extent of religious beliefs and rituals, the meanings and implications of ideological assumptions and local loyalties, and the nature and exploitability of everyday practices. All these data had to be elicited, translated, interpreted, and ordered within familiar conceptual categories that could make practical sense of the land and the people in order to form the New Spain out of highly ethnocentric and aggressively self-interested city-states.

To this effect, what today would be called ethnography drew the attention of some of the early conquerors (particularly Cortés himself),[24] priests, and secular officials, so that by the early 1530s missionary-ethnographers were formally instructed to collect the information needed to found a productive and peaceful colony.[25] Of the various institutions charged with the creation of new knowledge about the Indians, the Inquisition seemed to hold the most promise. After all, it enjoyed overwhelming support on the part of Church and Crown, and it appeared to have access to the maximum force needed to extract confessions, draw forth information, and punish those who remained silent or otherwise resisted its claims.

A close study of trial records nonetheless suggests that the efficacy of the Holy Office as a punitive system and the quantity and variety of information the inquisitors could elicit were limited by a number of factors. First, quite apart from the ruses and manipulations that sometimes precipitated inquisitorial accusations (denuncias or informaciones ), charges were formally restricted to the types of crimes and breaches legally recognized as within the competence of the Holy Office. These included a significant but extremely small number of categories of acts that needed to be controlled by the colonial powers (see Table 1.2, A). Second, there were legal restraints upon the interrogative procedures used that made it difficult for important but excludable information to enter the record. Third, the extreme and public nature of the penalties could serve as a warning to many but did so at the price of moving the key rebels who resisted the colonial order further underground, where it became more difficult to uproot them.[26] Fourth, the cultural and demographic barriers between Indians and Europeans, the Holy Office's legalistic procedures, and the Inquisition officials' constant concern with status—all called for levels of financing, energy, and personnel that spelled the need for the institution to focus its attention and resources on what it knew best and ultimately feared most: heresy and deviance among Europeans. Not surprisingly, of the 152 procesos tried by Zumárraga's tri-

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

bunal, ninety-three were for crimes associated almost exclusively with Europeans: blasphemy, heresy, Judaizing, and clerical crimes (Table 1.2, B).[27]

Together, these restrictions contributed to making the Inquisition a poor mechanism for meting out the type of punishment needed to effectively regulate masses of unacculturated Indians. But what ultimately marginalized the Holy Office from the efforts to subjugate the native populations was the widespread deployment, during the first half of the century, of two related practices: sacramental confession and missionary ethnography. Because each of these was far more pervasive and intrusive than the Inquisition, together they were more efficient at gathering the kind of information needed to transform the Nahuas into disciplined subjects. Elsewhere I take up the role of the penitential system as an inciter of discourse on the self and as an apparatus of self-formation;[28] here my sole concern is to study how, in the first half of the sixteenth century, a shift took place from the inquisitorial techniques of random investigation and selective punishment to a technique of penitential discipline that sought to affect each word, thought, and deed of every individual Indian.

From Punishment to Discipline

The responsibility for the forced acculturation of the Indians moved from the Holy Office to the (seemingly) less stringent local offices of the bishops (known as the provisorato del ordinario ) in 1547 (see Moreno de los Arcos, this volume). The archival record attests to the timing of this de facto shift in jurisdiction because only one relevant case[29] appears between that date and 1574,[30] by which time the Holy Office had already lost its official jurisdiction over the indigenes (see Table 1.1). Although the change of venue is nowhere explicitly explained or noted, the letters sent to Zumárraga in 1540, after he had had don Carlos executed, suggest the outline of a new policy. Translated into today's analytical language, the critical points in the instructions to the archbishop could be summarized—and were justified then—as follows:

1. Punishment, by functioning as part of a regime of exercises aimed at disciplining through indoctrination, is to be discreet and to have the self (mind/soul), rather than the body, as its object. That is, instead of torture, rigorous punishments, or scandalizing executions, what was needed was for the Indians "first to be very well instructed in and informed about the faith . . . because gentleness should be applied first, before the sore is opened with an iron."

2. The source and end of the discipline are to be invisible. For instance, "the little property they possess" should not be confiscated "because . . . the Indians have been greatly scandalized, thinking that they are burned on account of the great desire for these goods."

3. The discipline is to be made imperceptible by appearing to be evenly applied throughout the whole social body. In effect, instead of teaching them a lesson through rigorous persecution, "the Indians would be better instructed and edified if (the Inquisition) proceeded against the Spaniards who supposedly sold them idols, since they deserved the punishment more than the Indians who bought them."[31]

I will continue by analyzing the meaning and implications of each of these points.

Punishment and the Disciplining of the Soul

Scholars have made much of the humanism the first point seems to imply. The call for tolerance is an echo of the arguments developed in the late 1530s by Las Casas[32] to attack the superficial and sometimes violent means with which the Spanish officials and Franciscan friars sought to impose the new faith on the Indians. However, a survey of the

methods used by the missionaries during these early years attests to the futility of Las Casa's appeals for moderation.[33] It could not have been otherwise. The popular idea that natives needed to be treated in a special manner (because they were new to the faith, because they had a weak understanding, or because they were inclined to vice, etc.) originally arose out of very real political exigencies, although the specific conclusions may have been drawn from speculative reflections on ethnographic data or theology. However contradictory, policy was primarily driven by the pragmatic requirements of the colony, although, as is the case today, in official discourse the need to control was frequently masked by lofty language that expounded on the humanity of subordinates.

A particularly vivid example of the rhetorical, rather than empirical, nature of assessments of native capacity to acculturate is suggested by the following fact: almost thirty years after the letters to Zumárraga were written, the priest Sancho Sánchez de Muñón, while advising the king about the need to establish a Tribunal of the Holy Office in the New World, could still argue that

[the Inquisition] would be one of the most important things in the service of God, for use against the Spaniards, mulattoes, and mestizos who offend our Lord [but] for now it should be suspended in what concerns the natives because they are so new to the faith, weak [gente flaca], and of little substance .[34] [My emphasis]

In effect, the movement toward leniency was less the product of the reformers' rejection of the spectacular punishment of criminal acts, which continued for the Indians in an attenuated form at the local provisorato del ordinario level, and more a recognition, on the part of most priests and secular officials, that what colonial order called for most was the eradication from Indian life of the myriad of seemingly banal deviations from Spanish cultural habits and social customs. The friars, in their letters, sermons, doctrinal works, and detailed manuals for confessors, were quick to argue that every gesture and thought, from those associated with sexual life and domestic practice to the magical and empirical procedures employed in agriculture, the crafts, and social relations, had to be disciplined, retrained, and rechanneled, so as (I would add) to serve the interests of those who wielded power in the colony.[35]

To discover and punish these minute illegalities, systematic and pervasive forms of intervention were necessary. In this situation the Inquisition's attention to the scandalous cases of a few indigenous cult leaders[36] was clearly a dangerous and wasteful display of colonial power. Furthermore, too much delinquency went unperceived by most Spaniards and

was primarily confined to the private or local spheres, which were too numerous to be handled with the juridical safeguards called for by the inquisitorial process. Meanwhile, as these minor infractions continued to escape the grip of the authorities, they helped to reinforce and legitimate sociocultural and political alternatives to the habits and practices necessary for the formation of a homogeneous, predictable, and submissive population.

Although the need to impose some form of consistent and uniform discipline had been coming to light since the early 1530s, a substantial division in the Spanish perception of the level and nature of native resistance to Christianity made it impossible to implement one. On the one hand, Zumárraga's Inquisition, charged with defending the assumptions and practices that articulated Hispanic culture, had the debilitating effect of propagating the idea that native heterodoxy continued primarily as a result of heretical dogmatizing by a few indigenous religious leaders. On the other hand, some of the Franciscans, especially Motolinía,[37] a key figure in the Christianization process since 1524, were claiming that the natives were seeking salvation by the millions and were quickly forgetting the beliefs of the past. On one level, these representations were slowly being challenged by the ethnographic studies undertaken during this time, primarily those begun by Olmos in 1533.[38] On another level, the varieties of regional experiences and the urgent need for immediate control were leading some priests to the realization that local knowledge of the Indians was fundamental to the development of the type of discipline capable of forming "docile bodies."[39] If this latter call for widespread, rather than selective and exemplary, intervention had failed, the Indian Inquisition might have continued—as it did for the other more assimilated racial castes.

The Indian Inquisition, however, did end. And, in particular, its demise came about because it had been organized to function only among the baptized, who presumably already shared with the inquisitor the basic idea of what was and was not an infraction. If this is the case, it follows that the Holy Office was ill suited to discipline a people who did not share its basic cultural or penal assumptions. Before the spectacle of the stake could move beyond striking fear in the hearts of the natives to transforming their behavior permanently, they had to know the prohibitions of the Holy Office and accept the illegality of the things prohibited. Only an efficient system of indoctrination could make these prerequisites a reality.

But an effective proselytizing strategy had to go far beyond violent or physical coercion, the performance of baptisms, or the teaching of

the rudiments of the Christian doctrine. It had to penetrate into every corner of native life, especially those intimate spaces where personal loyalties were forged, commitments were assessed, and collective security concerns were weighed against individual ambitions. Thus, "the invasion within"[40] could not be done by scare tactics, whose ultimate result would more likely be resistance than acquiescence, but rather by shifting the moral gears to produce social and political effects that favored the interests in stability and productivity of those in power. An operative indoctrination that could produce such results had to begin with the widespread, but localized, imposition of a constant regime of moral calisthenics through corporal and magical punishments (like the threat of the first of Hell). These exercises, backed by the threat of the provisors, had to have as their aim the retraining of the individual in order for him or her to internalize a Christian form of self-discipline that would ultimately make external force secondary or unnecessary.[41] This intrusive strategy sought to constitute the most discreet punitive mechanism possible: a fear of divine retribution nourished by a scrupulous consciousness of one's wrongdoings. And where this failed, as it very frequently did, it excused the policing intervention of the priest, with his threats of supernatural punishment, corporal penance, and public shaming and ridicule. It also permitted pious neighbors to force the sinner to behave properly by threatening to exclude him or her from the moral and civic community. It was a brilliant experiment in mass subordination: the costly punishment of individual bodies by colonial officials or the Inquisition could be replaced, for the most part, by the economical disciplining of myriads of souls.

The Invisible Origin and Object of Discipline

The authorship and end of inquisitorial punishment were always evident. The source was obvious to all: Spanish hegemony—a force coming ultimately from the same external apparatus that inflicted innumerable other penalties and burdens. To the Indians, almost all of whom remained unacculturated in the 1540s, its ends were equally apparent: to deprive the accused of his or her traditions, the guiding memory of the ancestors, personal liberty and dignity, corporeal well-being and temporal property, and life (or so it must have seemed after the execution of the cacique don Carlos). Since at this early date the crimes the Inquisition sought to punish were not generally regarded as illegalities by the still unacculturated community, the Holy Office depended primarily on

the exercise of power rather than assent. It therefore lacked the legitimacy to turn scandalous punishments into moral lessons.

In contrast, the transparency of the discipline the friars sought to establish had as its source a continuous and permanent project of acculturation at the margins of Spanish life. The ritual origin and legitimating structure of this program of assimilation, which historians traditionally identify as "conversion,"[42] was a baptism which, in the early colonial situation, the friars had effectively transformed into a new social contract. Thus, unlike inquisitorial punishment, which turned the native subject into an object of punitive force, baptism, the voluntary acceptance of a new social pact, could force each party to it to participate as an active agent in his or her own punishment.

On one level, this new social contract was put into effect by the forces that were slowly appropriating for themselves the authority to determine both the rules of civic life and the nature of the new colonial truths. At the points of general concentration, and therefore penetration, these forces appeared in the form of local priests who (genuinely, for the most part) sought the temporal and symbolic (or supernatural) well-being of the Indians. Their good intentions had the rhetorical and emotive capacity to transpose agency, making the initial phases of indoctrination appear to be the voluntary acceptance of new rules of behavior and new codes of belief. Colonial power thus could circulate at a symbolic level that erased in its very movements the origins and ends that drove it. At another level, the new social pact, by resting on the rhetoric of magic,[43] could be enforced by the manipulation of punitive signs,[44] whose supernatural source was continually preached and whose human origin could thus remain hidden from the believers. The source of the new discipline was consequently made invisible by making it appear as if its fountainhead were either the individual, who voluntarily assumed it, or a deity who commanded it from above: Its end, the peaceful subordination to and productive loyalty on behalf of the colonial powers, was reconstituted as the personal quest for temporal well-being and supernatural salvation.

The Ubiquity and Uniformity of Discipline

The letters to Zumárraga underlined how important it was that inquisitorial punishment appear to be justly assessed and evenhandedly applied. As already noted, this was not possible as long as the Holy

Office had jurisdiction over such a culturally heterogeneous population as the one in New Spain. By weaving the new discipline into the personal and public strands of native and Spanish lives, however, the friars could be seen to cover with it all social and cultural sectors. The widespread use of an apparently common Christian doctrine, penal code, and ritual cycle was at the heart of this tactic.

Furthermore, by introducing the Christian sacraments in ways that made them coextensive with the life-cycle rituals of everyday indigenous life, the missionaries attempted to reify these rites and their meanings so that they would appear to be normal and universal. The ultimate result was to make the Christian practices accessible through the native registers of common sense, thus giving them the appearance of being natural and ubiquitous, while freeing them of the need to justify themselves on other grounds. Of course, the sporadic public punishment of non-Indians that continued after 1547 reinforced this image of penitential discipline as general and uniform.

In effect, the domestication and normalization[45] of millions of unacculturated Indians by dozens of friars needed far more than an Inquisition. It called for a new regime of control that acted upon the soul to create self-disciplined colonial subjects. Unfortunately, an analysis of the methods used to effect this end, primarily through a penitential discipline founded on confessional practices, is beyond the scope of this volume, but it is taken up elsewhere.[46]

Bibliography

Alberro, Solange. "La Inquisición como institución normativa." In Seminario de historia de las mentalidades y religión en el México colonial , edited by Solange Alberro and Serge Gruzinski. Departamento de Investigaciones Históricas, Cuaderno de Trabajo 24. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1979.

———. La actividad del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición en Nueva España, 1571-1700 . Colección Científica, vol. 96. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1981.

Axtell, James. The Invasion Within; The Contest of Cultures in Colonial North America . New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Baudot, Georges. Utopía e historia en México: Los Primeros cronistas de la civilización mexicana (1520-1569). Translated by Vicente González Loscertales. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1983.

Behar, Ruth. "Sex and Sin, Witchcraft and the Devil in Late-Colonial Mexico." American Ethnologist 14 (1987): 34-54.

Cortés, Hernán. Cartas y documentos. Introduction by Mario Hernández Sánchez-Barba. Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa, 1963.

Cuevas, Mariano. Historia de la iglesia en México. 4th ed. 5 vols. Mexico City: Ediciones Cervantes, 1942.

Doctrina cristiana en lengua española y mexicana por los religiosos de la orden de Santo Domingo. 1548. Reprint. Madrid: Ediciones Cultura Hispánica, 1944.

Fabian, Johannes. Language and Colonial Power. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

García Icazbalceta, Joaquín. Don Fray Juan de Zumárraga: Primer Obispo y Arzobispo

de México. Edited by Rafael Aguayo Spencer and Antonio Castro Leal. 4 vols. Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa, 1947.

Gibson, Charles. The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule: A History of the Indians of the Valley of Mexico, 1519-1810. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1964.

———. Tlaxcala in the Sixteenth Century. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1967.

———. "Indian Societies Under Spanish Rule." In Colonial Spanish America . Edited by Leslie Bethell. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

González Obregón, Luis, ed. Proceso inquisitorial del cacique de Tetzcoco. Mexico City: Archivo General y Público de la Nación, 1910.

———. Procesos de indios idólatras y hechiceros. Mexico City: Archivo General de la Nación, 1912.

Greenleaf, Richard E. Zumárraga and the Mexican Inquisition, 1536-1543. Washington, D.C.: Academy of American Franciscan History, 1961.

———. "The Inquisition and the Indians of New Spain: A Study in Jurisdictional Confusion." The Americas 22 (1965): 138-166.

———. The Mexican Inquisition of the Sixteenth Century. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1969.

Hanke, Lewis. The Spanish Struggle for Justice in the Conquest of America. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1965.

———. Aristotle and the American Indians: A Study in Race Prejudice in the Modern World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1970.

Klor de Alva, J. Jorge. "Martín Ocelotl: Clandestine Cult Leader." In Struggle and Survival in Colonial America . Edited by David G. Sweet and Gary B. Nash. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1981.

———. "Spiritual Conflict and Accommodation in New Spain: Toward a Typology of Aztec Responses to Christianity." In The Inca and Aztec States, 1400-1800: Anthropology and History . Edited by George A. Collier, Renato I. Rosaldo, and John D. Wirth. New York: Academic Press, 1982.

———. "Sahagún and the Birth of Modern Ethnography: Representing, Confessing, and Inscribing the Native Other." In The Work of Bernardino de Sahagún: Pioneer Ethnographer of Sixteenth-Century Aztec Mexico . Edited by J. Jorge Klor de Alva, H. B. Nicholson, and Eloise Quiñónes Keber. Vol. 2 of Studies on Culture and Society. Albany: Institute for Mesoamerican Studies. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1988.

———. "Sin and Confession among the Colonial Nahuas: The Confessional as a Tool for Domination." In Ciudad y campo en la historia de México . Edited by Richard Sánchez, Eric Van Young, and Gisela von Wobeser. 2 vols. Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1990.

———. "Contar vidas: La autobiografía confesional y la reconstrucción del ser nahua." Arbor 515-516 (1988): 49-78.

Las Casas, Bartolomé de. Del único modo de atraer a todos los pueblos a la verdadera religión. Edited by Agustín Millares Carlo. Translated from the Latin by Atenógenes Santamaría. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1942.

Molina, Alonso de. Confesionario mayor en la lengua mexicana y castellana. 1569. Reprint, with introduction by Roberto Moreno. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1984.

Motolinía, Toribio de Benavente. Memoriales: o, Libro de las cosas de Nueva España y de los naturales de ella. Edited by Edmundo O'Gorman. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1971.

———. Historia de los indios de la Nueva España. Edited by Edmundo O'Gorman. Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa, 1973.

Taussig, Michael. Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Tentler, Thomas N. Sin and Confession on the Eve of the Reformation. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1977.

Two—

New Spain's Inquisition for Indians from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century

Roberto Moreno de los Arcos

It is common knowledge that the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition was expressly prohibited from interfering in cases involving Indians. "Thank God," the distinguished Spanish historian Guillermo Céspedes del Castillo adds recently in the volume dedicated to the colony from his Historia de España .[1] What has not been made common knowledge is that this does not imply in any way that the Indians were exempt from punishment for transgressions of the faith. In effect, throughout the entire colonial period and well into the nineteenth century, there existed an institution expressly dedicated to punishing the Indians' religious offenses, identified by various names: Office of Provisor of Natives, Tribunal of the Faith of Indians, Secular Inquisition, Vicarage of the Indians, Natives' Court. This institution generated an enormous number of trials, very few of which have come to light.[2]

Ignorance of this tribunal's existence is based partly on the fact that historiography on the colonial Church is basically furnished by clergymen and Catholics eager to exalt Spain's efforts in America and to cover up the incidents that might appear negatively to liberal minds. The undeniable existence of the Holy Office of the Inquisition has been so well documented—so worn out yet so poorly understood by politically liberal writers—that this other capacity the Catholic Church had (and still has) to inflict punishment should have been discovered. What is evident is that a great number of colonial books do exist, clearly revealing all the details of the inquisitorial procedure regarding Indians, but it seems that we cannot see the forest for the trees.

Most of the known trials of that tribunal have been published and

studied as "sources" of indigenous ethnohistory. This they are, in effect, but primarily they are trials that can be used as a source for many other investigations, although it seems to me that the first one should be the study of the particular institution that generates them. In and of themselves, like any other documents, they are of no use as a study of what they do not contain.

It would be unjust to affirm that there has been a universal ignorance of this institution's existence. Obviously, those who created it knew about it, as did those it punished. I am more concerned with emphasizing the recent investigations of this institution, and I will refer to only two.

At the end of the nineteenth century, a Mr. Carrión, a Protestant, published a gallery of renowned Indians.[3] Among the Indians in that gallery was a Dominican Indian, Friar Martín Durán, whose existence was invented, and who was supposed to have been burned at the stake by the Holy Office for heresy. Don José María Vigil, director of the Biblioteca Nacional at the time, consulted with the scholar don Joaquín García Icazbalceta regarding this case. The latter had already published a letter debunking the myth, and with his characteristic prudence, had arrived at the conclusion that the falsifier's intention was to create the existence of a pre-Lutheran Indian in sixteenth-century New Spain. Among Icazbalceta's many arguments refuting the truth of this history is that of jurisdiction. He demonstrates that an Indian would have been subject to trial not by the Holy Office but instead by the authority of the ecclesiastical judge (i.e., the bishop or archbishop) through the Natives' Court.[4]

Much more recently, Professor Richard E. Greenleaf, with great insight and acumen, has clarified the issues. In an article published in 1965 in The Americas , he studies both tribunals, the Holy Office and the Office of Provisor, along with what he terms "jurisdictional confusion." This article allows us to clarify the underlying causes regarding the punishment of the Indians' transgressions of the faith as well as to establish a historical perspective of the facts. In this first essay, Professor Greenleaf's principal subject is the Holy Office.[5] His second article, published in the same journal in 1978, deals with inquisitorial trials against Indians as ethnohistorical sources and presents a compilation of invaluable information on this theme. It also includes a list of trials initiated against Indians, derived from the Archivo General de la Nación (AGN), principally from the Inquisitorial branch, as well as half a dozen from the National Welfare branch.[6] In these investigations as well as in the author's other works dedicated to studying the Holy Office, the problem I am focusing on has been well outlined.

My investigation of the subject takes a different approach. It focuses

uniquely on the Office of Provisor, ignoring the Holy Office completely, except when for some reason they coincide. This is, in short, the history of an institution's ecclesiastical-jurisdictional power over the Indians. As can be easily understood, this is a major undertaking that must confront enormous difficulties. We are dealing with vast documentation generated throughout three centuries, very difficult to access, of the dioceses and archdioceses of Mexico City (in this case the sources are located in part in the AGN, Bienes Nacionales, and in part in a locale which I cannot recognize since the destruction of the Mitre in the earthquake of 1985), Oaxaca (which involves its own difficulties), Chiapas (which is organized and now publishes a bulletin), Yucatán, Michoacán (now publicly accessible since it is considered the property of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia), and Guadalajara. The undertaking is impossible without a team of historians. I trust I will be able to organize one and offer the initial results by 1992, with catalogs of the trials and lists of the provisional judges of each diocese. The bibliography of the colonial books I have discovered on this material is presented in this essay and will soon be published, in an identical edition, as the Bibliotheca Superstitionis et Cultus Idolatrici Indorum Mexicanensium , beginning with Diego de Balsalobre's classic treatise. In this essay, I offer a summary of the problem and will allude to the progress of the investigation.

No one is unaware that the Church's power over society, like that of the state, has two axes composed of its authority and its territory—that is, its jurisdiction or power to set standards, to revise sentences, to correct, and to punish, and the territory or demarcation within which all of this can take place. As an example that will serve for what follows, we remember that many medieval Spanish cities contained more or less isolated precincts known as Moorish mosques and Jewish synagogues. Civil jurisdiction over these spaces fell to the state; the Church had no jurisdiction over them. The Christians would enter by force in order to baptize Moors and Jews, thus making them liable to ecclesiastical jurisdiction. They were prosecuted afterward if they willingly apostatized or attempted conversion through peaceful entrance into the precinct, a privilege enjoyed only by the Franciscan order. Those who were Christianized in this way were known as moriscos or judíos conversos . If this was not the case, then they maintained their own faith and could not be forced, a fact which is, it will be recalled, the cornerstone of Friar Bartolomé de Las Casas's argument in his defense of the Indians.[7] Jurisdiction and territory are also the axes in the Americas of what Ricard, a Catholic, called "spiritual conquest,"[8] and Duviols, a liberal, called "destruction of the indigenous religions."[9]

Primarily, jurisdiction over the "faithful" is exercised by the bishop

or ecclesiastical judge within the confines of his territory, which are almost always clearly delimited. The necessity of conserving the faith and its orthodoxy led to the creation, generalized in the Old World, of the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition against Heretical Perversity and Apostasy. Its jurisdiction, which was above that of the bishops, exceeded the diocese but not the kingdom. The principal crimes that it originally prosecuted were Christians' acts of heresy, that is, departure from or error concerning dogma in its two forms, material (i.e., through ignorance or confusion) and formal (through pertinacity),[10] and apostasy, or the rejection of the true faith in order to embrace another religion, which was fundamentally the case with the conversos .[11] This last crime was punished with the severest penalties. The catalog of punishable crimes expanded with the passage of time, and the Tribunal of the Holy Office gained enormous importance and respect. It is worth remembering here that "inquisition" simply means "investigation." It was the tremendous weight of the Tribunal of Faith that led to the semantic change, so that its exclusive claim to inquisition was recognized and sanctioned.

The encounter with the New World created many problems. To understand what occurred jurisdictionally, we must refer to the theological underpinnings. The Holy Scriptures, dictated by the Holy Spirit, say in the New Testament that Christ's apostles preached throughout the entire world.[12] Such a decisive affirmation thus authorized created quite a difficulty for Catholic theologians, since the New World was populated by millions of human beings, none of whom were Christian. In the face of such a reality, some explanation had to be found. The most ingenious theologians postulated that the intentionally lost apostle, St. Thomas, had preached in the Americas. The foundations were taken from the indigenous myths like that of the priest Quetzalcóatl, whose alleged kindheartedness the Catholic priests were set on promoting. This thesis, which also occurred in Peru with some variations, arose in the sixteenth century and was expunged by the nineteenth.[13] It did not actually flourish, because among other things, it implied the brutal fact that the entire continent had apostatized. The practical solution was to declare that the existence of the New World was a mystery and that the Indians were "gentiles" (that is, without ever having received Christian doctrine), and to set about evangelizing them. The Church was able to do this because they deemed the Indians "idolaters," among other negative things.

Idolatry is an unpardonable error for Christianity. It consists of offering latria , or worship and service owed solely to God (the worship of the saints is called dulia ), to an idol, an image created by human beings.[14]

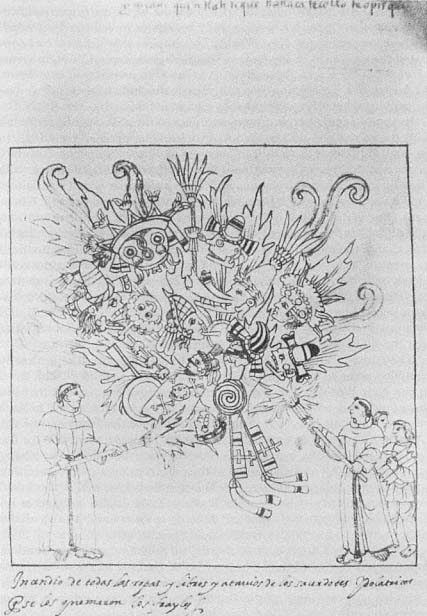

Fig. 3.

"Bonfire of clothing, books, and items of idolatrous priests burned by the friars."

That the Indians were idolaters provides one of the principal justifications for what Spanish historiography continues to call the "just titles" of the conquest of the New World. This implies that if Spain had conceded the existence of the Indians' own religion, it would not, in terms of what has been said above, have had Christian jurisdiction over them. As far as civil jurisdiction was concerned, the Indians were alleged to be, among other things, drunkards and sodomizers.

In spite of some heroic attempts to slacken the zeal, Spain proceeded with the conversion of New World Indians. The process turned out to be more difficult than had been anticipated. The main problem is that, in spite of the friars' investigations which are our principal sources, the Indians had their own religions and were unfamiliar with Christianity, unlike the Moors and the Jews, who had centuries of contact with Christians. The two religious mentalities confronted each other without mutual understanding: one exclusive, that of the Christians, and one inclusive, that of the indigenous peoples. This reality has been conceptualized in terms of "syncretism" or "nativism," and yet these terms are not completely satisfactory. The fact is that the Christian Church expanded its battlefronts. It did not simply have to contend with the heretical deviations or the apostasies with which it was familiar in the Old World, but now saw itself forced to employ its imagination regarding the novelties that the Evil Spirit manifested in America.

The Church held that the Devil was the guilty party. I have already compiled some notes toward an essay that could be entitled "The Devil in the New World."[15] He was the one responsible for the veil that hid these lands and peoples from European eyes. He had fooled the Indians into worshipping him with excrements in place of the sacraments of the Church of God and as a mockery of divinity. He was responsible for the fact that the Indians committed crimes against the faith after having been baptized. All of this resulted in the primary necessity of exorcising lands, animals, plants, and people. This resulted, I believe, in the initial Franciscan practice of limiting the baptismal rite. It also resulted in indispensable and constant vigilance in order to detect and punish all deviations, that is, to exercise ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

According to Llorente, inquisitional jurisdiction was introduced in America when, by order of Charles V, the cardinal inquisitor Adriano named don Alfonso Manso, bishop of Puerto Rico, and Friar Pedro de Córdoba, vice-provincial of the Dominican Islands, as inquisitors of the Indies and other islands on 7 January 1519.[16]

Regarding New Spain, jurisdiction arrived with the famous "first twelve" Franciscans headed by Friar Martín de Valencia. This privilege

was derived from Pope Adrian VI's bull dated 10 May 1522, entitled Exponi nobis and known as Omnimoda , which stated that "in case there were no bishops," the friars could act as secular clergy and exercise the jurisdiction corresponding exclusively to the bishops.[17] This produced two interesting historical outcomes. The first generated a peculiar conflict that lasted for almost three centuries regarding the Spanish state's efforts to secularize the Indian parishes, finally achieved with great effort around 1770. The second concerns the topic I am now addressing.

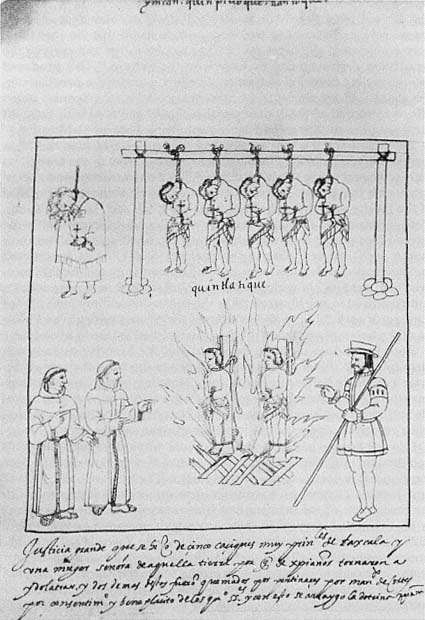

The first twelve Franciscans received episcopal jurisdiction as well as jurisdiction of the Holy Office and that of inquisitors of the Indies, on their passage through the West Indies.[18] The Franciscans arrived in New Spain with this power, prepared to exercise their authority. The head of the faculty was, obviously, Friar Martín de Valencia. We have incomplete information about the number of trials he initiated, but as he formed part of that reality which severely punished apostates, we know that in 1526, one year after the evangelization of Tlaxcala, he ordered the hangings of at least six men and one woman from among the "most principal caciques" in various autos de fe , as attested in diverse sources and portrayed in two illustrations in the codex that accompanies Muñoz Camargo's work.[19] I have always believed that these acts deprived Valencia of the honor of sainthood that his order wished to bestow upon him.

Since jurisdiction could be delegated and the Franciscans had complete control in this area, it is on record that in the following year, 1527, Friar Toribio de Benavente, the humble Motolinía of our literature, sentenced the conquistador Rodrigo Rangel to one day at mass with a candle and nine months in a monastery for blasphemy.[20] Scant information exists regarding this primitive inquisition by the secular clergy.

I do not know whether it was intentional, but everything seems very well thought out. The Spanish Crown sent to Mexico Franciscans whose vocation was conversion, as we noted earlier. The first bishop of Mexico, Fray Juan de Zumárraga, was also Franciscan, with ample experience in the extirpation of witchcraft in the Basque provinces. The "elect one," as he was called, arrived in New Spain with episcopal jurisdiction in 1528. Since it fell to Zumárraga, Friar Martín de Valencia and his companions immediately yielded the jurisdiction they had exercised for four years, "although he refused it," according to the document of cession.[21] In 1534, Zumárraga was invested by delegation with the office of inquisitor. In this capacity he carried out dozens of trials, among which many of the published ones are of increasing interest.[22] The most well known is that of the cacique don Carlos de Texcoco, which ended with his death at the stake in 1539.[23] When the king found out about it, he

Fig. 4.

"Great punishment of five major caciques and one woman for obstinancy

and returning to idolatry after becoming Christians."

angrily issued a decree condemning Zumárraga's action, saying that since the cacique's life could not be returned to him, all his belongings should be returned to his kinsmen, and he prohibited the maximum penalty for Indians, "tender shoots in faith."[24] This decree thereafter saved Indians from execution on grounds concerning the Christian religion.

The following and third chapter on jurisdiction concerned the inspector Tello de Sandoval, who, between 1544 and 1547, was employed as apostolic inquisitor and carried out various trials.[25] Zumárraga had been tacitly relieved of this function, although his episcopal jurisdictional powers were not suspended.

Between 1548 and 1569, jurisdiction reverted to the bishops, since the Holy Office had not named any inquisitors. Very little is known about the trials during these years. At any rate, the Omnimoda bull was not abolished, and the evangelists were able to exercise their authority in areas without bishops. Between 1561 and 1565, Friar Diego de Landa authorized trials in Yucatán leading to harsh denunciations which he was able to dispel in Spain, aided by the aforementioned bull.[26] As far as we know, the missionaries exercised jurisdiction in areas without bishops (as in the case of the Jesuits in Baja California in the eighteenth century—a fact which certainly must have terrorized the enlightened Hegel).

After much hesitation, the Spanish Crown resolved to reestablish the Inquisition in American territories in 1569.[27] Their purpose had much to do with the prosecution of the old crimes of heresy and apostasy that were its traditional target, given that the colonies were being infiltrated in an effort to avoid the Old World tribunals, as was amply demonstrated later on. In the document regarding the creation of the Holy Office in America, the king expressly prohibited interference in Indian cases and preserved the bishops' authority.[28] Beginning at that time, in civil as well as ecclesiastical matters, New Spain was decidedly split into two republics, that of the Indians and that of the Spaniards (including all types of Europeans, criollos, mestizos, blacks, mulattoes, etc.).[29]

Consequently, after 1571, when the Holy Office of the Inquisition was formally established in Mexico, two tribunals of the faith existed until 1820, at which time the first tribunal was definitively closed and the bishops published edicts proclaiming their recuperation of total jurisdiction.[30] We are thus studying a very active institution that arose in 1548 and disappeared—if indeed it has formally disappeared—quite recently. It is well worth our efforts to make a thorough study of it.

Three—

The Inquisition's Repression of Curanderos

Noemí Quezada

As an ethnologist, I have focused my interest on the curanderos, or folk healers, of colonial Mexico in order to explain both their persistence and their continuity in medical practice. I also wish to define the role of the curanderos and to examine their importance within this evolutionary social process, for the curanderos' knowledge and skills contributed to the health of the oppressed and led to the formation of a traditional mestizo medicine that syncretized Indian, black, and Spanish folk medicines. These categories of analysis confirm the important social function of traditional medicine and its practitioners who offered a solution to the health problems of the majority of the population of colonial Mexico.

The necessary existence and function of the curanderos in New Spain can be attributed to the scarcity of doctors.[1] The authorities allowed for their presence and practice with a degree of tolerance that came to characterize the prevailing social relations in the American colonies, allowing not only for the continuity of traditionalist medicine but also for the beliefs and practices of the ancient pre-Hispanic religions as a means of resistance.[2]

The Crown was politically conscientious in establishing a legal medical system for Spaniards, thus protecting the health of the group in power. The Indians, and eventually the blacks and mixed castes, were assigned the practices of the curandero. Yet this division along class lines went ignored; Spaniards frequented the curandero as much as the other groups. Given its social dynamics, traditional medicine permeated the entire New Spanish society.[3]

If the curanderos were necessary, then why were they pursued, tried,

and punished by the Holy Office of the Inquisition? The contradiction presents itself in ideological terms: on the one hand, their services were required as experts on the human body, as able surgeons, and as superior herbalists; on the other hand, they were harshly repressed for the magical part of their treatment, which frequently contained hallucinogens and which the authorities, according to the Western world view of the time, viewed as superstitious.[4] The authorities intended to prove that medical expertise derived solely from Spanish medical knowledge; they would thus invalidate the entire medical practice of all other practitioners and justify their condemnation.

The Curanderos and the Holy Office[5]

From the very beginning of the conquest of New Spain, the Spanish Crown attempted to impose a Catholic world view upon which to base a system of normative practices that would organize the entire society within the framework of religion. The problems presented by the social and ideological heterogeneity of New Spain were extremely difficult to solve. The colony's reorganization was carried out along administrative, economic, and political lines, but resulted in a different dynamic on religious and cultural levels. The goal was to unify the entire society under the Catholic faith, which in actual practice was interpreted and molded according to each social group's conception. Despite the Church's efforts to disseminate its official doctrine through regular and secular clergy with the support of the civil authorities, the various social groups—mixed castes, Indians, and marginalized Spaniards—perceived Catholicism as an ideal impossible to live up to on a daily basis. Thus, the religious beliefs of New Spain reveal a process of syncretism reflecting popular religion and culture.

At times even unconsciously, civil and religious authorities strove to achieve their assigned goal of social integration; unity, however, was at best superficial in a society where diverse ideologies coexisted and interrelated, ultimately resulting in a less strict and orthodox situation than in Spain.[6] The unification of Spanish society under the reign of the Catholic monarchs, as well as the Church's gradual loss of political power as it increasingly came under monarchical control, had repercussions in the American colonies, where the lack of jurisdictional limits over control and conservation of the faith led to frequent confrontations between civil and religious authorities. To maintain order and to ensure the system's equilibrium, constant vigilance was needed via the institution created in Europe in the thirteenth century and adopted by the Catholic

kings at the end of the fifteenth century:[7] the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, which functioned as a disciplinary apparatus, "an organism of internal security,"[8] controlling dissidents within the religious, moral, and social order.

The first missionary friars were invested with the powers of the secular clergy where there was no priest or bishop, and they were responsible, among their other duties, for the detection and punishment of all violations of the faith.[9] No case of curanderismo appears registered under the first commissioners of the Holy Office.

Fray Juan de Zumárraga, the first bishop of New Spain, received inquisitorial powers in 1535, and he established the episcopal inquisition with a tribunal and inquisitorial functionaries in 1536. Under his supervision, which lasted until 1543, twenty-three cases of witchcraft and superstition were tried, probably including some cases of traditional medical practices.[10]

Petitions first circulating in the middle of the fifteenth century explained the need to establish a Tribunal of the Holy Office which, like that in Spain, would have total disciplinary control, thus avoiding the frequent abuses and jurisdictional equivocations of the civil authorities. Philip II authorized the tribunal in 1569 with royal letters-patent, and it was established in New Spain in November, 1571. As in Spain, the New Spanish inquisitors were, above all else, men of law who scrupulously carried out their duties in order to maintain social control.[11]

After Zumárraga had condemned the cacique of Texcoco to the stake for idolatry in 1539, causing him to be removed as inquisitor, the question arose as to whether the Indians should suffer inquisitorial penalties since the Crown was legally responsible for their guardianship and protection.[12] Fully aware of the abuses committed by the provincial commissioners supervised by the bishops during the episcopal inquisition, Philip II decided to leave the Indians outside the control of the Holy Office and placed them under the ordinary jurisdiction of the bishops.

Although the royal decision was respected, inquisitorial commissioners did receive accusations against the Indians. For some of these commissioners the separation of jurisdictions was quite clear;[13] for others, confusion, jealousy, or the belief that the crime merited inquisitorial punishment incited them to apprehend, reprimand, and threaten the Indian curanderos.[14] Once the denunciation was issued, it was important to determine whether it concerned "pure Indians" or mestizos; to remove all doubts, the Holy Office thus required that the commissioners formalize the proceedings with documents such as testimonies.[15]

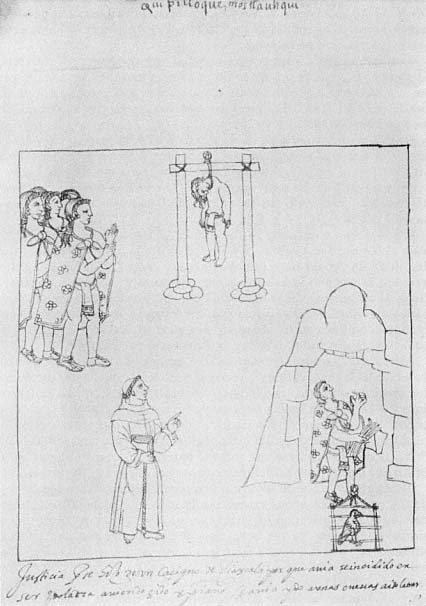

Of the thirteen cases concerning Indians found among the proceed-

Fig. 5.

"Punishment of a cacique of Tlaxcala for falling into idolatry after becoming a Christian."

ings I have examined, that of Roque de los Santos, who was accused as a mestizo, appears to be illegal. During the course of the trial, it was discovered that he was an Indian; nonetheless, he was sentenced, and it remains unclear whether sentencing occurred because he was part of the same trial as Manuela Rivera, "La Lucera," or because the inquisitors decided that the punishment was appropriate for a mestizo. Proof of this racial status was furnished in a document not included in the proceedings. He was sentenced to be paraded in a cart preceded by a town crier who announced his crimes, to receive two hundred lashes, and to labor eight years in a mining hacienda.[16]

The Curanderos Punished by the Holy Office

Of the seventy-one delations and denunciations which the Holy Office received against curanderos, fourteen warranted attestations and were dismissed after being considered inappropriate. Twenty-two cases were tried which called for testimony; in fourteen cases the inquisitors decided in favor of public or private reprimand, two suffered public humiliation, only one had a public auto de fe in the Church of Santo Domingo, and one was exiled. These were the maximum punishments suffered by the curanderos.

The first cases specifically recorded in the registers of the Inquisition as offenses of curanderos were those of Francisco Moreno, a thirty-year-old Spaniard accused of healing by incantation in 1613, and the mulatta Magdalena, for having taken peyote as a divinatory aid.[17]

From this time until the beginning of the nineteenth century, the accusations against the superstitious curanderos give descriptions of the therapies that identified specializations and the use of herbs and hallucinogens in the curative ceremonies. Most importantly, they attempted to understand the practitioners of traditional medicine and their patients, disclosing the latter's reactions and fears regarding the unknown, the mysterious ways of those who dealt with their health, and patients' belief in their powerful supernatural faculties.[18]

It was also a common belief that bewitchment and all incurable illnesses resulted from hatred or unrequited love. Between these two poles revolved the relationships of New Spanish men and women; seeking good health, they appealed to the curanderos, yet when undergoing treatment, sometimes positive and other times negative, they often fell into the contradictory position of thinking they had violated the norms imposed by the Holy Office. This reaction, quite natural for the times, accounted for the detailed records of the inquisitors which have fur-

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

nished us with all the cultural data needed to confirm the continuity of curanderismo within medical practice, to determine its changes, and to specify the concepts and judgment of that medical practice, formed, on one side, by the curanderos defending their practices and, on the other side, by the inquisitorial authorities who wished to repress them.[19]

The Accusations

Self-accusations were unusual, perhaps because the curanderos did not consider their practice a crime. Only Francisco Moreno and Mariana Adad denounced themselves. The former found out in an Edict of Faith that the occupation of spell-caster (ensalmador ), which he had practiced for many years in various cities in New Spain, was prohibited; presenting himself before the inquisitorial commissioner of Oaxaca, he sought clemency through his open declaration of ignorance. In her report, Mariana minutely describes her case, from predestination since infancy through her initiation and practice; she was confident that the inquisitors would assess her healings as a gift from God.[20]

Delation was the most frequent reason for detention given in the reports, and it is not surprising to discover that the majority of the delators were the former patients of the accused curanderos. On occasion, knowledge of an edict that had been posted on the doors of the church and had been read by the priests during mass on Sundays or holy days aroused unrest and fright, unleashing in turn a series of accusations made by the informers "in order to relieve the conscience."[21]

When the informer presented him- or herself before the inquisitors at the Holy Office in Mexico City, the provincial commissioner or priest with inquisitorial authority swore to keep the secret. The informer was asked what type of declaration he or she was prepared to make, since the kind of process depended upon whether it was merely a delation or an actual accusation. The prosecutor of the Holy Office made the accusation after hearing the attestations and presenting the case before the qualifying judges.

In spite of the declaratory oath, it is probable that the actual reasons for a delation were hatred or resentment when the cure had negative results, at times worsening the patient's condition, or when the curandero had refused to attend a sick person.[22] In those cases where the remedy had positive results, the patients, having disobeyed the faith by resorting to forbidden practices and specialists, sought to lighten the punishment they believed they deserved by accusing someone else. Neither family nor romantic ties were exempt in these circumstances.

Feelings of impotence in the face of illness, fear of the unknown, envy, competition, and fear inspired by love, all impelled New Spaniards to the Holy Office.[23]

Delations presented through public rumor were received and investigated. Between one and four attestations were sufficient to ensure continuation of a case. In some cases, the curanderos' public reputation became an issue with the priests or civil authorities, as it caused a public disturbance and loss of control over the faithful; the priests then had the responsibility of making the accusation to the Holy Office.[24]

When provincial commissioners or priests with inquisitorial authority were involved, they usually sent the complete delations and reports to the commissioners of the Holy Office beforehand, so that upon receiving a response from the qualifying judges they would know how to proceed with each case.[25] Inquisitors were responsible for the most stringent enforcement of the rules and regulations of the Holy Tribunal. They often expedited the Instructions to ensure the correct methods of inquiry and to obtain greater information in order to standardize judgment by the qualifying judges, thus avoiding, wherever possible, errors that might discredit the prestige and deplete the treasury of the Holy Office.[26] There were few cases where the accused could not be located, either because too much time had transpired between the crime and the accusation, or because he or she had died.[27]

The Trials

Once the delation or report was received and the trial subsequently endorsed, the first step was to call upon the witnesses, dismissing those cases where interrogation revealed that they had been motivated by hatred, desire to defame, or other similar reasons. Witnesses presented by the informer or called by the commissioner were advised of their responsibility and the importance of their testimony, as well as of the punishment incurred if their testimony should prove false or motivated by hatred or enmity. In accord with the rules, witnesses were assured of and sworn to secrecy.[28]

The purpose was to gather as much information as possible in order to continue the trial or to dismiss it. Although the number of witnesses in the cases of curanderos varied depending upon the offense committed, it was usually determined by the conscientiousness of the commissioner. For example, more than twenty witnesses were called in the trial of María Tiburcia, while eleven were called in the trial of Manuela Josefa; in general, the average number was four or five witnesses. In the

case of Petra Narcisa, six testimonies were presented, and since the information was considered insufficient to decide the case, the trial was rescheduled and six other witnesses were called in order to define the charges.[29] Moreover, it was common to request testimony from the curanderos' former patients, relatives, or assistants.[30]

Detentions and Imprisonment

The judges ruled whether or not to proceed with the trial on the basis of the testimonies, with the prosecutor of the Holy Office presenting the formal accusation.[31] Once the decision to proceed had been made, the accused was detained and placed either in the secret jails of the Holy Office, in the curate jail, or in the royal jails; in some cases, women were taken to houses of correction.[32] The goal was to interrogate the accused as many times as necessary.

When the prisoner was placed in the jail of the Holy Office, a very meticulous physical description was made, along with a description of all articles of clothing, other personal belongings, and bed clothes.[33] In six cases the prisoners' belongings were confiscated, and in only one was it noted that they were "few and poor." The other five cases make no mention of the value, from which we can infer that the total was unimportant. Transfer of prisoners from the interior of New Spain to the jails of the Holy Office in Mexico City was done infrequently, since the expense was covered by the prisoner's own possessions. Where there were no possessions, the tribunal covered the expense, ordering a careful examination of "the quality of the person and the nature of the offense, and the trial to take place only under great consideration."[34]

There were anomalies in the detentions; for example, when Miguel Antonio and his wife presented themselves to denounce Manuel José de Moctezuma, all three were imprisoned. The curandero was set free, but the denouncers were detained for an additional period of three days and received a sharp reprimand for having taken pipiltzintzin , a hallucinogen recommended by Manuel José.[35] Priests who made arrests without the authorization of the Holy Office were also severely reprimanded, and if the civil authorities tried to make arrests, the inquisitors protested the encroachment on their jurisdiction.[36]

The length of time in prison varied with the duration of the trial; in general, it fluctuated between the three and five years it took to complete the trial. Only the prison cells of the Holy Office were safe and adequately guarded; in other locations the prisoners were able to escape. One curandera did so by burning down the door; although she was able

to escape, she was captured because she was very ill. "El Churumbelo" escaped through the rafters of the jail ceiling, but he was captured and returned to prison. María Margarita, with the help of her daughter, escaped in shackles. Among the fugitives was José de Roxas, arrested for teaching forbidden prayers to children; he was the only fugitive who was never captured.[37]

The Confession and Torture

The interrogations of the curanderos proceeded in the usual way. In general, they accepted the charges and confessed correspondingly; only Agustina Rangel denied the eighty charges imputed to her. "La Cirujana," feigning insanity and sickness with hallucinations of snakes, almost managed to deceive the inquisitors and avoid indictment.[38] The interrogations provided proof complementing the accusations against the prisoners. For example, Lorenza, an elderly midwife, never "wished to declare the kinds of herbs" that she used in her healings. In these cases, specialists were sought to identify the medicinal plants in order to determine if they were prohibited.[39]

All of the punitive rules and regulations of the Holy Office were based on physical punishment: not only torture but deprivation of liberty, imprisonment in dark, humid cells, solitary confinement, whipping, and even the public exhibition of the prisoners in specific clothing and the parading of male and female prisoners naked to the waist were all degradations not easily forgotten by the individual or society. That was, after all, the objective: to conserve a vivid memory of the punishment.

In two cases of curanderos, both were tortured in order to obtain confessions: José Quinerio Cisneros, a mulatto whose file contains the decree that torture be applied, because of his reluctance, "one or more times, as much as is necessary,"[40] and Agustina Rangel, aware of the inquisitorial mechanisms, who declared that she thought she was pregnant, since she "finds herself with great pain in the belly and hips." This excuse most probably postponed both trial and torture.[41] Despite the torture, Agustina continued to deny the eighty charges pressed by the prosecutor, repeating before the inquisitors if she had cured people, it was by "the grace of God and of the Holy Virgin and Santa Rosa," who helped and advised her, Santa Rosa entering her body to cure the sick. The qualifying judges were the ones who asked the prosecutor to torture her, to see if she would confess the truth.[42] Convinced of her revelations, she insisted on denying the charges even after torture. When she was sentenced in October 1687, two years after she had

been detained, she again denied the charges. Not until February 1688, when the sentence was carried out, did she admit to them.[43]

The Sentences

The most frequent punishment against the curanderos was a reprimand with a prohibition against their practices. In most cases, the reprimand took place privately before the commissioner, the notary, the prosecutor, and the inquisitorial witnesses, gathered together at the trial's final hearing when it took place in Mexico City. In other places, it was made before the representatives of the Holy Office. Public reprimand was carried out by the same officials with six, eight, or more witnesses.[44]

The reprimand was meant to be a lesson to the accused, and the justification was that in many cases no other punishment was applicable, since "because of their backwardness they cannot be charged with any heretical intention," or because they had committed the offenses "without malice, only in order to avoid working and to swindle innocent people."[45] The reprimand was severe and its threat was important. The tribunal took harsh measure against recidivists. After the reprimand, the prisoners would make an oath promising not to repeat the offense. Juan Luis, a black man, was warned he would receive public reprimand of twenty-five lashes at the church door if he did not honor his oath.[46] "La Cirujana" was a recidivist, who, because of her illness, did not receive any major punishment and was placed in a convent.[47] Moreover, reprimands were issued against ignorant witnesses and denouncers.[48]

Public Punishment

Public punishment functioned as an educational ritual of inquisitorial power. The principal assumption was that exemplary punishment would prevent New Spaniards from committing offenses. Francisco Peña is emphatic about the concept of punishment: "The primary objective of the trial and death sentence is not to save the soul of the accused but rather to procure public welfare and to terrify the populace."[49]

The penitents, carrying candles, gagged, and wearing tunics, coneshaped hats, and nooses, covered with symbols indicating their offenses, were exhibited publicly, their crimes published and repeated by the town crier. The prisoner was thus penalized not only by inquisitorial authority but by the entire society as well, represented by those participating in the ritual. People who attended the ritual liberated themselves

through self-expression in the ceremony, and they learned from the punishments not to commit the same offenses. They saw the penitents' sufferings in these rituals that catalyzed the repressive New Spanish society. The goal of publishing the penalties was to avoid social transgression, disequilibrium, and rupture.