2

Containing the Rock Gesture

Despite the backlash against rock 'n' roll, the moralization drive under way could banish neither the demand for the new rhythm nor the yearnings of youth, who sought to follow in the footsteps of their foreign teen idols. In fact, government efforts to blockade the arrival of foreign music indirectly contributed to the emergence of a native rock 'n' roll product that rapidly supplanted imports. What this debate over mass media did affect, however, was the content of an emergent Mexican youth culture. By placing clear boundaries on artistic expression, the recording companies, television, radio, film, and print media collectively promoted an image of Mexican rocanrol stripped of its immoral associations, thus rendering a form of "high" popular culture also suitable to the modernizing aspirations of the middle classes. Indeed, rocanrol served as an apt metaphor for the modernizing Revolutionary Family itself: cosmopolitan, consumerist, yet bounded. The new youth culture was literally contained by the cultural industries, which at the same time nurtured and marketed it.[1] Though its content was framed by production and marketing enterprises wary of provoking conservative reaction, Mexican rocanrol nevertheless had a profound impact on the transformation of everyday life for urban youth, above all from the middle classes, during this so-called Grand Era of Mexican rock 'n' roll.[2]

Transnational and Local Marketing Strategies

When youth from the middle classes began to form their own bands in the late 1950s, practicing as best they could versions of hit songs in English by their favorite foreign rock 'n' rollers, the recording companies initially took scant interest in their efforts. The market for music was still defined by imports, on one hand, and by Spanish-language ballads and música tropical,

on the other. From the industry's perspective, competition for the youth market largely came down to which companies had access to foreign artists. Leading this pursuit was RCA, which distributed Elvis Presley, and Rogelio Azcárraga's company, Orfeón, which distributed The Platters as well as Bill Haley and The Comets. In fact, the latter two groups were actually brought to Mexico City by Orfeón in late 1959.[3] But by this date, Orfeón's own strategy had begun to change as it weighed the rising costs of imports against the lucrative potential of local bands recording Spanish-language cover versions for a wider market.

With the growing importance of foreign markets for recorded music during the late 1950s, one of the transnationals' strategies was to promote an artist by producing several versions of a hit sung in the local language, most often French, Italian, Spanish, or German. The idea was to preempt competition from a version of the same song performed by a local artist. In one case, for example, Elvis Presley sang two verses of his song "Wooden Heart" in (phonetic) German. Peter, Paul and Mary also later recorded in German and French as well as Italian.[4] Even the internationally renowned Mexican group Trío Los Panchos reportedly recorded in Japanese for Columbia Records.[5] The recording companies found "the procedure [of translation] highly economical since only the vocal has to be re-recorded, with the instrumental part being taken over from the original tape."[6] Ironically, this switch to local-language translations was a reversal of an earlier trend by European performers who had made English-language versions of their own hits "slanted to crash the American market."[7] Noting that "the growth of the international market...has opened up a vast new revenue potential," a vice president and head of artists and repertoire for Capitol Records pointed to a Spanish-language recording of Nat King Cole (which had sold 100,000 albums in Latin America) as an example of the direction that foreign marketing must take.[8] Likewise, the new vice president for Latin American operations at CBS recommended that "the American publishers should prepare Spanish lyric versions of their songs along with the English"[9] as a measure of countering the ease with which local cover versions of a popular song were being produced. Such covers threatened to dip directly into the profits of the transnationals. As one agent of the music industry noted, "The cover appears so quickly that in many cases the American company does not have the opportunity to get its record released."[10]

In Mexico, the recording company Orfeón can claim credit for first cultivating local talent as a response to demand for imports. Though a relatively small company, Orfeón had important connections to other mass media—the Azcárragas collectively owned a network of radio stations, published

various music-oriented magazines, and monopolized the infant television industry—and thus the necessary motivation and flexibility to experiment with new ideas. As José Cruz Ayala, former artistic director for several companies, including Orfeón, during the 1960s, recalls:

[Orfeón] had more advantages as a domestic operation at a given moment because they were less structured in terms of the use of studios, etc....I'm not saying that CBS was totally different, but obviously there was a difference in policy. At Orfeón there was nearly unlimited access to the studios, compared with CBS, which had its headquarters in New York and thus dictated policy from there. Furthermore, CBS had an extensive catalog featuring all types of music, whereas Orfeón did not. So [Orfeón] could actually dedicate more time and money to that type of recording [rock 'n' roll].[11]

According to Federico Arana, sometime in late 1959 Rogelio Azcárraga of Orfeón pushed its artistic director, Paco de la Barrera, to contract a group that could perform rock 'n' roll covers of foreign hits in Spanish.[12] This was a strategy for maneuvering itself into a more competitive position vis-à-vis the transnationals. Naturally, because the latter had greater access to foreign recordings their attitude toward covers was more conservative. Johnny Laboriel, former singer with Los Rebeldes del Rock, one of the most important groups to emerge during this period, describes his experiences producing covers, first for RCA and later for Orfeón:

Because it's a case of duplication [with a cover], you have to make it even more real for the people who receive it. It's like, for example, if I recite a lot of catechism for people whose native language is Náhuatl, I'm going to have to adopt it to their reality. That's what happened with rock 'n' roll taken from English. In the beginning, for instance, the director of RCA-Víctor, Rafael de la Paz, was totally against doing covers. He wanted us instead to sing rock 'n' roll versions of Mexican music. He tried to have us do a song called "La borrachita," a dreadful thing....We said, "Forget it, this isn't going to work." So we went to Orfeón Records, where they accepted us, and the only Mexican song we ever played to the beat of rock 'n' roll was "La bamba."[13]

In an interesting tale, an artist-and-repertoire person at CBS reportedly risked his own savings to record a new group, Los Teen Tops, against the wishes of the general manager, André Toffel, when he "realized that rock 'n' roll in Spanish was going to cause a commotion in the market for records."[14] Within days, two of the group's songs—"La plaga" (a cover version of "Good Golly Miss Molly," by Little Richard) and "Rock de la cárcel" (a

cover of Elvis Presley's "Jailhouse Rock")—shot to the top of the charts in Mexico and, shortly thereafter, in Spain and parts of South America as well.[15] As it became clear that Spanish-language covers had broad appeal, RCA did an about-face and quickly zeroed in on the burgeoning market throughout Latin America created by rocanrol. Thus in the fall of 1960 RCA transferred its artistic director, Ricardo Mejías, from its Mexico City subsidiary to Buenos Aires. In Argentina, Mejías "launched a new wave' of disk talent, with the accent on youth, in marked contrast to RCA's former policy of plugging the favorites of the past." Within a matter of months, record sales in the Southern Cone soared, and the subsidiary began "registering its biggest sales of any time in its close to 40 years in Argentina."[16]

By early 1961, the bandwagon effect caused by the sudden switch to Spanish-language rocanrol had completely transformed the industry. While literally scores of songs were performed in a rock 'n' roll style, Variety reported that around "25 clicked really big with [the] public and about 90 to 100 others just barely held their own."[17] It was overwhelmingly a movement started by and aimed at middle-class youth, who suffered most from the high cost of and limited access to imports. Forming a band was an economic challenge, but one that offered lucrative potential as the market for music suddenly opened up. As Manuel Ruiz, an ardent rock 'n' roll fan from the era, recalls:

The first rock groups were formed around 1959–1960, when people first began to get hold of instruments imported into Mexico. There weren't any at first; here no one made them....They were expensive and not just anyone could say, "I'm going to buy a guitar and drum set and form my own band." No, the instruments were expensive! You needed to have money and couldn't be too poor, although a lot of people bought them on layaway. But even this took a lot of sacrifice if you were from the middle or lower-middle class.[18]

Mexico's Grand Era of rocanrol (1959–1964) mostly centered in the nation's capital district, though its influence reached far beyond the district's borders. Largely performing covers—or refritos, as they were called—bands with such names as Los Loud Jets (Orfeón), Los Locos del Ritmo (Orfeón), Los Rebeldes del Rock (Orfeón), Los Teen Tops (CBS), Los Black Jeans (Peerless), Los Hitters (Orfeón), Los Hooligans (Orfeón), and many others became not only national stars but, in certain cases, international ones as well.[19] "The avalanche hit so hard," recalls Johnny Laboriel of Los Rebeldes del Rock, "that suddenly you heard only rocanrol on the radio. All of the

jukeboxes played rocanrol. And then the cafés cantantes [music clubs] came into being."[20]

From Rock 'n' Roll to Rocanrol

Virtually every song recorded during this period was a translation of a foreign hit imposed on the musicians by the recording companies themselves. When rock 'n' roll first arrived in the mid-1950s singers had naturally tried to imitate the English original. As Johnny Laboriel tells it, "The first time I heard rock 'n' roll was on the jukebox. We used to go to this ice-cream café, and it was there that we started to hear what it was all about. I remember the first word I heard was 'darling,' but shouted out like this!...So that was the first thing I did. I started to sing rock 'n' roll. But I didn't know any English...[so] I used to sing to the girls, making up the words as I went along."[21] Singing in guttural English undoubtedly came across as more authentic, but it was largely impractical for recording. (Gloria Ríos was an exception, with her masterful rendition of Haley's "Rock around the Clock.") Moreover, because of the close associations between rock 'n' roll and rebeldismo, copying the English original connoted a level of authenticity that record producers were at this point anxious to tone down. What was needed was a Spanish-language equivalent that maintained the essential rhythm and structure of the original (with perhaps some token English thrown in) but that provided greater control for producers who needed to deflect assaults by conservatives. For Orfeón, the process was simple: "We saw what was a hit in the United States...and then we brought in the record, in fact even before it was sold here [in Mexico], and we immediately made a cover version with one of our [contracted] groups. Then we promoted it on television and radio...and in twenty-four hours we had a record on the street for sale."[22] Marketing Spanish-language covers of foreign hits was a strategy that directly undercut the transnationals' inherent advantage, as José Cruz Ayala explained:

In an album by Los Teen Tops, there exists the best of the best as a copy, so it already had a certain preestablished sales value. They were already covering a series of points—one already knew which songs were going to be hits....You took the recordings by Elvis Presley and could choose not just one but lots—there were easily twenty to forty songs that one could make a cover out of—and this was the same with the recordings of whatever other person that occurred to us.[23]

Such was the popularity of rocanrol that despite a 1961 recession that affected record sales in other Latin American markets, Billboard reported

that "[t]he significant and still increasing trend of 1961 in Mexican music has been the absolute predominance of rock in record sales and radio programs," performed by the "dozens of teen-age singers and 'wild' rock groups [that] have been and are still recording."[24]

Rocanrol was above all a middle-class phenomenon, which neither replaced the mass appeal of more traditional musical styles nor reached much beyond urban consumers of the capital and provincial cities. Nonetheless, its impact significantly realigned musical tastes and fashions, in the end redefining an image of Mexican modernity that had been overly dependent on the stereotyped mariachi performer. For example, in early 1961 an agreement was reached between Channel 5 of New York City and Tele-sistema to initiate an exchange of videotapes featuring how each country had influenced the other's musical styles. Not by coincidence, the first program was "devoted to [the] invasion of Mexico by rock-and-roll rhythms, with [the] top groups interpreting the frenzied music appearing in the segment."[25] According to a report in Variety in early 1961, rocanrol had "eclipsed all other melodies," leading to "one of the poorest years [for traditional music] because of the frenzied switch to rock and roll."[26] Government policy, which had aimed to influence popular tastes by threatening sanctions against radio stations dominated by foreign-language songs, now adopted the added position of a protective tariff. In mid-1961 the tariff on imports went from U.S. $0.005 per kilo on records with a 10 percent ad valorem to U.S. $1.20 per kilo and a 40 percent ad valorem. This meant that the average cost of an imported record increased around 50 percent, resulting in a notable drop in imports [27] (see Graph 2). While the tariff undoubtedly reflected the combined pressures of musicians' unions, nationalist government officials, and local media interests, its impact was twofold. First of all, it forced a shift toward local pressing from the masters which, where available, now replaced imports. Billboard, for instance, reported at the end of 1962 that "90 per cent of records formerly imported are now pressed locally."[28] This created a boon for local production. Secondly, however, the new tariff also induced record companies across the board to market a native rocanrol product as a more flexible substitute for costly imports.

Indeed, a 1962 report by the Banco Nacional de Comercio Exterior indicated that "modern rhythms" were "displacing the music that is authentically Mexican." The report argued that the popularity of such rhythms had created incentives for the recording industry to tailor domestic demand according to trends set by "those countries from which modern music originates."[29] Clearly, the marketing trends were being set by styles imported from abroad, and the record companies, both locally owned and transna-

Graph 2.

Record imports into Mexico, 1955–1976. Source: Anuario del Comercio

Exterior (Mexico City: Banco Nacional de Comercio Exterior, 1955–1976).

tional, were active participants in the process. Orfeón, for instance, in addition to promoting its own contracted artists, had signed an exclusive, two-year contract with Bill Haley "to handle r'n'r rhythms in Spanish, to [the] accompaniment of Mexican musicians."[30]

Best epitomizing this influence was the international sensation caused by the twist. At the start of 1962 Variety was reporting that "the [twist] dance craze has spread around the globe,"[31] and RCA's Mexican subsidiary was quick to promote the style locally, seeing it as an opportunity to " 'rejuvenate' traditional Mexican songs."[32] As Rubén Fuentes, artistic director at RCA-Vfctor Mexicana, said, "We will give a Latin twist to The Twist," pointing out that such standards as "Bésame mucho" would be "adapted to 'twisting.' "[33] In an effort to arrest this "exotic rhythms kick," the Mexican Society of Authors and Composers, in collaboration with the National Tourist Council and the major record companies, promoted a Mexican Song Festival as a way to "renew interests in national tunes."[34] Still, an artistic director at CBS argued that Mexican composers would benefit "if they

would learn to keep up with the times and musical fashions, and create accordingly." This position was backed by a spokesperson at Orfeón, who urged that composers should pursue "new ways of expression" aimed at youth.[35]

Reaction to the popularity of rocanrol varied, with certain radio broadcasters eagerly promoting it while others viewed it as anathema and deemed it "vulgar, obnoxious and in bad taste."[36] One radio station, for example, flatly refused to program rocanrol calling it "a sample of bad taste that we must avoid at all cost."[37] Calling them "musical rebels without a cause," Alfredo Urdián, an executive with the powerful Mexico City Musicians' Union, announced a boycott in October 1960 of any establishment that allowed young rockers to perform, arguing that the measure was necessary to protect "legitimate musicians" from "unfair competition."[38] This campaign was underscored by a petition to the Office of Public Entertainment asking it to issue a decree prohibiting dance halls from hiring, in Variety's words, the "youthful musical maniacs."[39] Yet two months later it was announced that an Association of Rocanrol Units was being formed as an ad hoc union for the musicians. According to the group's president, Antonio Figueroa, its purpose was to "'dignify' rock and roll in Mexico and to weed out questionable elements," such as "student or worker groups who 'think' they can interpret rock and roll rhythms."[40]

This reflected a fundamental ideological element of the movement, which was to be reinforced at all levels of the media during the 1960s: the containment of rock "n" roll began with the musicians themselves but extended to all aspects of their media representation. Having vowed to "sweep the Mexican musical scene clean of the 'musical hoodlums,'"[41] even Venus Rey, head of the musicians' union, soon succumbed to the reality of rocanrol's popularity with the public. In a measure of the rhythm's inexorable march, now wholly backed by television and radio, by the fall of 1961 the musicians' syndicate had agreed to accept the rocanrol groups as "meritorious" members of the union but on the condition that for every rock 'n' roller hired, a "bona fide union musician" must also be contracted, a clause no doubt difficult for the union to enforce.[42] As a current director of sales at Orfeón, Carlos Beltrand Luján, now recalls, "Everyone had a friend in some [rocanrol] group. And they all performed in afternoon gigs.... [S]oon after their records came out, all of this pushed aside demand for the foreign groups. We all supported our [Mexican] groups and bought their records. Of the five or six radio stations that had supported foreign rock, only one remained.... The rest started to support rock in Spanish."[43] By the end of 1962 Billboard was reporting that the best-selling U.S. artists

were "[o]ut of favor, and practically never played at radio stations." "No English lyrics ... are accepted by the Mexican public," the trade magazine noted.[44]

As a result of Orfeón's all-out investment in rocanrol, the company saw its share of the total domestic market for all music increase from 2 percent in 1957 to 16 percent by 1962, still far short of RCA's 40 percent.[45] In fact, despite a climate of hostility and conflict with RCA and CBS, Orfeón's ties to other media placed the company at an important advantage over the transnationals, allowing Orfeón, according to Beltrand Luján, to capture around 80 percent of the rocanrol market by the end of this period.[46] Conflicts first emerged between Orfeón and RCA toward the end of 1961, when the latter sought to discredit Orfeón by claiming that it was headed toward bankruptcy, a charge far from true. In fact, the conflict in large part centered on Orfeón's undercutting the transnationals by developing "cutrate and bargain sale tactics," a strategy that had set off a price war in the industry.[47] But the price war was only one side of the picture that was emerging. The other concerned the transnationals' steady moves to compete with Orfeón for the rocanrol market. For example, CBS initiated an aggressive marketing strategy aimed at broadening its market share throughout Latin America, a company trend that accelerated throughout the decade. In an effort designed "to give [CBS] a stronger foothold in the international market," the company pursued a strategy "to have greater involvement in the local artists & repertoire production activities, creating [a] product for the specific country itself as well as [a] repertoire of value to the entire international area."[48] Thus, starting in 1961, new recording studios and expanded manufacturing facilities were built in Argentina, and the company announced that it had "launched long-range plans to broaden [its] distribution and recording operations in all major markets throughout the world."[49] During 1962, the company was reporting "excellent sales volumes ... by wholly-owned records subsidiaries in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada and Mexico."[50] In June 1962 CBS increased the capitalization of its Mexican subsidiary, which was now generating 352,000 records per month.[51]

Shortly thereafter, Orfeón began to accuse CBS of stealing its artists and dominating the newly formed Mexican Association of Record Producers, leading Orfeón to quit the association briefly in protest.[52] Meanwhile, CBS continued its advance into the Spanish-language markets, upgrading its facilities in Latin America and establishing a distribution contract with the Spanish recording company, Hispavox, through which Columbia Records' Latin American artists, such as Los Teen Tops, were now distributed in Spain.[53] In 1963, the transnational could report that the "Columbia Rec-

ords U.S. repertoire is not only now packaged, distributed and promoted throughout the world by foreign subsidiaries and affiliates, but, in turn, these companies record native artists which are marketed on a world-wide basis by Columbia."[54] With their offers of lucrative contracts and the accompanying benefits of recording for a global company, RCA and CBS quickly cultivated their own roster of Mexican rocanrol performers, often aggressively luring artists away from contracts already established with other companies. In various instances, for example, contracts with Orfeón were broken as performers switched recording companies.[55] In one notable case, Los Locos del Ritmo switched from Orfeón to CBS, where they were promoted throughout South America as well as the southwestern United States.[56] Indeed, via their recordings and appearances in film, groups such as Los Teen Tops, Los Loud Jets, and Los Rebeldes del Rock came to be widely known not only throughout the republic but also in Latin America, Spain, parts of the United States, and even Europe and Asia.[57]

While the transnationals had tremendous advantages—their economies of scale, direct access to cataloged material, and global marketing networks—Mexican companies were also able to compete for the rising consumer demand created by what the industry was calling la nueva ola, or "new wave" of youth-oriented music. Orfeón was best positioned to take advantage of this opportunity because of the company's complex ties to other mass media, but other local companies also profited.[58] Thus in 1960 Orfeón launched its own television program as a front for its contracted artists. Initially called Premier Orfeón, in 1962 the name was changed to Orfeón a go-go, which reflected its strong youth-oriented catalog under the popular Orfeón label. Around the same time as the start of Premier Orfeón RCA announced that it was following suit with its own weekly program to "featur[e] one or more of the firm's recording artists, as well as dance routines."[59] A score of dance-oriented television programs cropped up around the country in rapid succession. In short, the rocanrol boom affected the entire industry, from the recording companies to the radio and television networks. While exports of "traditional" Mexican music continued to show modest signs of increase during this period, especially to the growing Mexican American communities in the United States, domestic demand was dramatically displaced by la nueva ola of music groups targeted at youth.

Domesticating Youth Rebellion

If in the United States rock 'n' roll was under constant surveillance by conservatives in the media and in Congress—the containment of Elvis's ro-

tating hips on the Ed Sullivan Show and the payola hearings in Congress being the best-known examples[60] —in Mexico musicians ceded a priori control over their recorded material to the record companies. Original compositions were strictly curtailed, although one rocanrol composition, "Yo no soy un rebelde" by Los Locos del Ritmo, in fact became an important hit (see below). With closely matched renditions of the original composition and Spanish lyrics that often had little to do with the original, these songs came to be known as refritos, from the verb refreír (to re-fry). Suggesting notions of reappropriation and making anew, the refrito in fact came to embody the containment of rock 'n' roll via its Spanish-language domestication. As Víctor Roura, a contemporary rock critic, has written:

If with Elvis Presley the rock genre lost all of its roots (the song of blacks) to become another article of consumption, though with evident differences from traditional North American music ... here the Hooligans or Teen Tops or Rebeldes del Rock or Locos del Ritmo were obligated by their artistic directors to introduce only the scenic [aspect of the] movement. Never the pelvis offensively displayed. Mexican rock and rollers were always under artistic quarters. Not one contestable act (nor was there a reason for it). Not one intention of changing the direction of the song, much less modifying a way of life with their music.[61]

Rock 'n' roll's gestures of defiance were circumscribed by the record companies, the film industry, and ultimately the musicians themselves, who above all realized that the key to success and stardom was conforming to a discourse of nonthreatening rebellion. Rocanrol was promoted as mere entertainment, as just "another branch of the market for Music."[62] Carlos Beltrand Luján of Orfeón recalls how his company went to great lengths to promote an image of its contracted artists as studious and family oriented: "In sum, we made it clear [to the public] that this [musical] tendency was not doing anything to them, that they kept being good family children [hijos de familia ] who paid attention to their parents; that the girls who sang rock 'n' roll were not getting pregnant or anything."[63]

By introducing the musical rhythms of foreign performers, but with "homegrown" lyrics and a clean-cut image more palatable to the concerns of adults, the companies discovered a formula for naturalizing a cultural phenomenon previously regarded as controversial and even subversive. Víctor Roura's cynical point that "[t]he bourgeoisie imposed the beat" on Mexican rock 'n' roll is not entirely off the mark.[64] The reappropriation of rock 'n' roll as rocanrol suited an image of the modernizing Revolutionary Family, both in an economic sense—as Mexico shifted from an agrarian economy to an industrial one—and in a social sense, embodied in the no-

tion of greater communication between parents and children in an age of liberalizing values. Spanish-language rocanrol literally domesticated the imported rhythm by removing the stigma of rebeldismo that adults and the government had found threatening, while retaining the modernizing aspects that had such broad appeal. Symbolizing the commodity culture and technological achievements of a modern nation, the image of rocanrol promoted by the cultural industries steered clear of outright challenges to patriarchal authority. On the cover of a Jueves de Excélsior from early 1962, for example, we find a drawing of an entire family dancing to the new rhythm, from the hip-looking older son and daughter, to the parents, and even to the youngest children (see Figure 3). The text reads simply, "The family dances the Twist."[65] This image was not too distant from what may have really occurred, as one informant from a conservative Catholic family recalls. Noting that her mother learned to dance rocanrol "at the same time as we did," Conchita Cervantes explained: "She danced with us because she has always been outgoing, jovial. She even helped us out a lot. Like, she helped us to organize parties: she pushed back furniture, swept. She organized everything so that we could have a party." In this case her father was not a dancer in general, but even he "didn't mind parties, and he preferred that they took place in his own home rather than outside."[66] As a metaphor for modernity, Spanish-language rocanrol in fact conveyed an image of familial harmony, but always under the rubric of assent to parental guidance and restrictions.

The numerous youth-oriented films produced during the first half of the 1960s reflected this mounting containment of the youth culture, despite the fact that the reality was an increasingly uncontained attitude toward parental authority. While certain films dealt openly with themes of delinquency, these were linked directly with irresponsible fatherhood and the lack of discipline within the home. Unlike in Juventud desenfrenada, where absentee parents provided the premise for disorderly youth,[67] parenthood in these delinquency films is always redeemed; children and parents both repent and pay the price for their misdeeds. Moreover, mothers are never depicted in a negative light, whereas fathers are directly assailed for their failings. For example, in Juventud sin ley (Rebeldes a go-go) (Lawless Youth, 1965),[68] the arrest of two boys from rival gangs sets the stage for a drawn-out, didactic lesson in the meaning of fatherhood and the moral significance of motherhood. The background of one gang member reveals a working-class family in which a drunken father steals from his wife's earnings and blames her for their son's delinquency: "You're at fault for spoiling him!" he shouts at her early in the film. "Shut up, you're drunk,"

Figure 3.

"The Family Dances the Twist." Source: Jueves de

Excélsior , 1 February 1962. Used by permission.

she responds in a challenge deemed acceptable because the father had relinquished his patriarchal authority through irresponsibility. Meanwhile, the father lashes out at his son: "You're a bum with nothing to aspire to but being a delinquent!"

But it is the middle-class background of the second gang member that is more relevant (and it is he who becomes the focus of the film), since here the issues of delinquency were more troubling in their complexity. The mother is divorced and raising her son alone, though with the moral support of a symbolic father, a priest. Hiding the truth from her son that his father had left her for a younger woman, she allows him to grow up believ-

ing his father to be dead. In reality, the father is a politically connected judge who, with blatant hypocrisy, appears one night on television denouncing lax parenthood as the basis for rebeldismo. Learning of his father's true identity, the son assaults him one night in the hope of getting caught. His plan works, and the ensuing political scandal forces his father's resignation. But when the son accuses his mother of deception (for not telling him the truth about his father's identity), the father hits him: "Your mother is a saint. I was the bad parent." Scolded by the authorities with the words, "A good judge begins in his home," the father must now watch as his son is sent off to a juvenile penitentiary. There, to the rhythm of the band The Rockin' Devils, the locked-up boys sing:

|

Although the son languishes in jail, the incident has brought the parents back together. "Every day I admire and respect you more," the father says to his former wife, reinforcing her moral superiority. The film ends with mother, father, and son praying in church to the Virgin of Guadalupe (the ultimate symbol of motherhood) for her strength and guidance. As the priest approaches them, the father turns to his son and asks for his forgiveness. To this the son replies: "Forgive me father. Forgive me both of you."

In another film of this genre, La edad de la violencia (The Age of Violence, 1963),[69] again the relationship between delinquency and the redemption of fatherhood emerges as a central theme. Featuring the rising rocanrol star César Costa, here appearing (rather unconvincingly) as a Marlon Brando-inspired hoodlum, Daniel, a narrator opens the movie against the backdrop of a motorcycle gang roaming the streets of the Mexican capital late at night: "This is a true story to show youth that crime never pays," we are told somberly. Daniel's father was once an important doctor, but when he performed a failed abortion (leading to a patient's death) the mother fled in shame, and the father, having lost his license, turned to alcohol. Costa (Daniel) and his sister (Nancy), in turn, lose all respect for their father, and both fall into a life of crime. But when one of their robberies goes awry, a gang member is critically wounded, and Daniel compels his father to try and save him. Enforcing his own authority within the family of the gang, Daniel stages a mock assassination of a gang member blamed for the fouled robbery. But this too goes awry, and the member (in love with Nancy) is

killed. Called in to try and save him nonetheless, the father for the first time stands up to his son and confronts his own irresponsibility: "All of us are guilty. Me above all." His final act of redemption, however, is to turn the gang over to the police, declaring to Daniel: "A long time ago I stopped being your father." He indicates to the police: "Here, we are all assassins." In the final scene father turns to son, beckoning now with renewed moral authority: "Come, my son. You can still return to living and become a good man."

After 1962 such films were themselves displaced by others featuring jubilant youth (often the same actors) against the backdrop of rocanrol as an expression not of delinquency but, rather, of upwardly mobile aspirations and frivolous consumption. In comparison with their counterparts produced in Hollywood, these films avoided the dichotomy of "the college versus the corner,"[70] a central narrative feature of many U.S. teenage films. What they shared, however, was a strategy of presenting an alternative image of youth, one that "was a carefully constructed ideal, part of a systematic attempt to make teenagers nice ."[71] Unlike films such as Juventud sin ley and La edad de la violencia, the mere implication of economic want itself was conveniently purged from these later films, a return to the style characteristic of youth cinema from the mid-1950s (Juventud desenfrenada, discussed in the previous chapter, being an important exception).

While reactionaries such as the League of Decency are outwardly mocked, buenas costumbres are explicitly interwoven into the plot structure. In the film, Twist, la locura de la juventud (Twist, The Craze of Youth, 1962),[72] for example, the protagonist, Enrique Guzmán of Los Teen Tops (playing himself) pays for his college education by running a soda-fountain café where his band performs. "It's a place," as one character exclaims, "with rhythm!" In an opening scene the "League of Spiritual Health" arrives to close the café down, forcing the band to switch hurriedly from a twist version of "La cucaracha" to a waltz. Though Guzmán's rocanrol group is denounced by the league all the same, a sympathetic judge throws out the case for "lack of evidence." Determined to entrap him, a young female ideologue from the league (Rita) sets out to film Enrique dancing the twist—considered immoral—but the plan backfires, and her spying is exposed. Later apologizing for her actions, Rita says to Enrique, "I had a different idea of you. I thought you were a bad student who just wanted to have fun." To which he replies, "And what's wrong with having fun?" Rita decides that Enrique is right and joins his cause. Declaring that "each generation has its rights ... above all those regarding its own music," Rita

renounces all ties to the League of Spiritual Health and joins the world of youth and diversion, exclaiming, "Long live the twist!" The film ends with everyone from all generations, including the conservative members of the league, dancing the twist.

In another film, La juventud se impone (La nueva ola) (Youth Take Over, 1964),[73] via rocanrol intergenerational differences are resolved, and the family unit itself is strengthened. In this film, the modern metropolis of Mexico City symbolizes a country caught in the throes of progress. Rocanrol has the city enveloped; there is no escape from it on the radio and television. The plot revolves around attempts by César Costa and Enrique Guzmán to match their single parents with one another. Meanwhile, the sons' own romantic pursuits benefit enormously from their status as rising rocanrol stars. Costa's father, a widower, is an opera lover with great hopes that his son "can only make it to the Fine Arts Palace" by becoming an opera singer. The father, however, is completely inept with women and openly receives advice from his son on how to date. Guzmán's mother is also widowed, but with more modern habits and tastes (such as dancing the twist) and with a morbid fear of aging. Her image as a "modern woman" directly challenges the traditional view that widows must shield themselves from immoral distractions, forever mourning the death of their husband.[74] Yet at the same time, each parent is single as a result not of divorce but of circumstance; there is modern-day tinkering but no major affront to buenas costumbres. In an effort to set their parents up with one another, the sons deceive them by claiming that each is interested in what the other enjoys, that is, opera and twist. On their first blind date the parents immediately clash over musical tastes (symbolic of their traditional versus modern lifestyles) but decide they like each other anyway. Meanwhile, Costa and Guzmán become embattled in a fierce musical competition, a fight that embroils the entire city. Rocanrol is ultimately presented as a modern dance style that an older generation—even ardent opera lovers—can learn to appreciate. In the end, the dueling sons reconcile their differences by performing a ballad duet at the wedding of their respective parents, reflecting not only the moderation of youth but also the place of modern values in society.

After 1964, a spate of films with names such as Fiebre de juventud (Youth Fever, 1965), Amor a ritmo de go go (Love to the Rhythm of Go Go, 1966), and Los años verdes (The Wonder Years, 1966) continued their "cult of the rock and roll youth style," as Emilio García Riera characterized one such film.[75] Casting aside all associations with the real-life conflicts then

emerging, these films instead presented an image of youth in which generational and gender conflicts are resolved through mediation by the family and, where necessary, figures of higher authority.

In Los años verdes,[76] for example, the themes of sexuality, parental guidance, and benevolent authority are all tied together against the backdrop of rocanrol. The film takes place at an unnamed private university where men and women are kept from socializing, a situation that a young philosophy professor suggests to the school director needs changing. "There isn't a single reason [for the policy]," he tells the also young female director. "The kids get along in open comradeship without any other notion than healthy diversion. Sometimes I wonder if it isn't we the adults that, with our many prejudices, don't complicate the lives of adolescents, placing obstacles in their path when we should be removing them." The professor wins the director over to his side, leaving only an old woman administrator (dressed in black mourning) as a symbol of resistance to the new liberal order. Although the school brings together students from different social backgrounds by offering scholarships, the image of students presented is nevertheless one of luxury. None is truly destitute, and the line "a poor student, like me" uttered by one character suggests a notion of relative, rather than absolute, poverty as the main problem of society. When two students from different family backgrounds fall in love and are falsely accused by the old woman of having had sexual relations, they run away from the school out of shame. Finding them, the female director is forgiving and states that their real crime was not their feelings but their method of expression, that is, breaking the law by running away. Referring to the female student, Luisa, as "My child," the director instructs them both to "return without fear" to the symbolic family represented by the school. In a metaphor for the stern benevolence of the ruling regime, the director calls in Luisa's parents (her mother and stepfather who had "abandoned" her while they traveled the globe) and berates them for not being more attentive to the love and attention required by their daughter. The film ends with Los Hooligans performing a waltz in tribute to the benevolence of the director. Symbolizing the mediating role of music and the coherence of the larger societal family, the director accepts an invitation to dance with the philosophy teacher. The film closes with all couples, young and old, dancing a waltz together.

This image of a contained youth culture was promoted at all levels, from films, to radio, to the numerous fanzines of the period. The latter served a large teenage audience not only throughout the republic but, in the case of México canta, for instance, reaching Central and South American countries and parts of the United States as well. It is perhaps unsurprising to find that

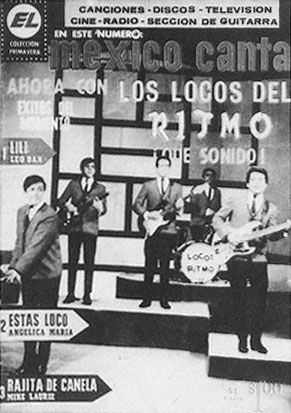

Figure 4.

México Canta featured the buttoned-down look

of refrito groups like Los Locos del Ritmo during the mid-

1960s. Source: México Canta, October, 1965, in the author's

personal collection.

these magazines presented a clean-cut image of rock 'n' roll, both Mexican and Anglo, which, after all, matched the global teenybopper fad (see Figure 4). As was true more generally, for instance, the pages of these magazines served as a medium for juvenile communication about such concerns as finding opposite-sex pen pals, discovering tidbits about the private and public lives of local and Hollywood stars, and learning the lyrics of the latest songs (often translated into Spanish). México canta was, in sum, "a magazine dedicated to youth gossip,"[77] a statement (sent in by a reader) that was no doubt apt for all magazines of this genre. Still, there was almost an exaggerated effort by writers to present an image of rocanrol as non-threatening, healthy entertainment. In an article on the twist, for instance,

one writer noted that while prohibited in certain places around the world, "every generation has its own craziness." He concludes by stating, "We are for the Twist because it is a healthy and fun dance."[78] In another example, a feature article on Los Locos del Ritmo opens by declaring, "They're not crazy! They're just four dynamic, happy, and enthusiastic young students in pursuit of a dignified career which provides them a clean and honest living."[79]

It is revealing, nonetheless, to witness efforts by the government's Qualifying Commission of Magazines and Illustrated Publications, which, at least in one case, sought to suppress the spread of magazines that openly exploited the public's taste for rocanrol. Dating from a licensing petition in January 1962, the magazine La Historia del Rock 'n' Roll y el Twist, was denounced for its very title which, according to the commission, "contains foreign words which have no grammatical significance whatsoever,"[80] a dubious attack, given that rock 'n' roll and twist were both part of the vernacular by that time. In fact, the magazine's title had mutated since its first issue. It started with the name La Historia del Rock 'n' Roll in November 1961; then Es la Historia de la Juventud was added in December; and it finally settled on La Historia del Rock 'n' Roll y el Twist for its fourth issue.[81] In a second petition for licensing, also denied, the commission noted that "this is a publication which directly exalts persons who have reached notoriety as singers of rock 'n' roll and twist ... such as Elvis Presley, Bill Haley, Paul Anka, Bobby Darin, Chubby Checker, etc." The magazine therefore "promoted customs foreign to our own" and fell within the limits set by the commission guidelines on censorship: "In that which is referred to as its literary content, this publication is dedicated to promoting the life and successes of artists and pseudo-artists who interpret recently created melodies, known by the names of 'Rock 'n' rol' and 'twist' which in recent days have reached a surprising and ephemeral popularity and that, in sum, are nothing but musical turns which directly damage proper taste and propose to eradicate authentically Mexican popular music."[82] Moreover, the magazine "utilized texts which systematically employ expressions which offend the correct use of the language, as is the actual title of the publication ... and, as is natural when dealing with foreign songs which, when translated employ vulgarized equivalents, the publication in question employs diverse words that are not Spanish."[83]

Although the commission's battle was ultimately a lost cause, the language and obstacles raised in these debates reveals the important presence of conservative influences that helped shape a contained discourse of youth rebellion. By the latter half of the decade, however, as the content and im-

agery of rock music became bolder (a point explored in the next chapter), the task of containment itself took new turns.

The Social Uses of Rocanrol

While the image of youth presented on the screen and in magazines was overwhelmingly one of conformity, the reality of rocanrol's impact on everyday life was often more decisive. Though the majority of songs from this early period dealt with themes of teenage romance and leisure time, they were written in such a way as to not offend adult morals. Yet in a society where girls were still prohibited from attending social events unescorted, where teenage dating was regarded as a trajectory toward marriage, and where children lived with their parents until—and even after—marriage, such songs staked out an important space for youth apart from, and even at times against the sensibilities of, conservative parents. In the song "La chica alborotada" (The Wild Girl, a cover of Freddy Cannon's "Tallahassee Lassie") by Los Locos del Ritmo, for example, teenage flirting is intimately tied to the new youth culture:

|

In an examination of several songs from this period one finds various references to the connection between rock 'n' roll and youth liberation that, if sanitized by the media presentation of the groups themselves, undoubtedly created important "slippages" that were exploited by young consumers. For example, in the refrito of "Good Golly Miss Molly," originally performed by Little Richard, Los Teen Tops' version, "La plaga," becomes:

|

|

Knowing how to dance is thus directly associated with being wild and breaking the rules, even if the lyrics return to marriage as the endpoint of the relationship. Interestingly, in the original lyric by Armando Martínez jefes (literally, old men, as in "my old man") is as padres, (parents), while the line "Vamos con el cura" (Let's go see the priest) is as "Esto ya va en serio" (This is getting serious). On the one hand, therefore, we see a transformation of a respectful discourse into colloquialisms; on the other, we see the substitution of a nonreligious referent for one with explicit ties to Church-sanctioned marriage. Still, this was a far more wholesome version of the song than Little Richard's, which also centered on the theme of the wild girl. The first stanza, for instance, goes:

Good golly Miss Molly,

sure likes to ball.

And when she's rock'n and a-rolling,

can't hear your mama call.

In other refrito recordings many of these groups consciously mimicked the linguistic intonations of Elvis Presley (while refraining from his patented pelvic thrust), Chuck Berry and others; though performed in Spanish, guttural references to the original were obvious. Presley's influence, especially, was strongly evident. This was reflected, for example, in a refrito of his song "King Creole," the title of the film that was the setting of the 1959 riot in Mexico City. In recording the song, Los Teen Tops directly referenced the ill-fated showing of the film two years earlier. And while there are noticeable similarities between the original and the refrito lyrics, significant differences are also present. The original goes in part:

There's a man in New Orleans

who plays rock and roll.

He's a guitar man with a great big soul.

He lays down a beat like a ton of coal.

He goes by the name of King Creole.

You know he's gone, gone, gone,

Jumpin' like a catfish on a pole.

You know he's gone, gone, gone,

Hip-shaking King Creole.

When the king starts to do it,

it's as good as done.

He holds his guitar like a tommy gun.

He starts to growl from 'way down in his throat.

He bends a string and "that's all she wrote."

You know he's gone, gone, gone....[87]

In the Spanish version, "King Creole" is not only a source of authenticity—as he is in the original—but, moreover, a site of knowledge, suggesting that those who have "seen him" (that is, in the film) really know what's going on:

|

What is notable about these songs is the fact that, despite a commercialized image of rocanrol as intergenerational (or at least inoffensive to adults), the

lyrics make explicit the connection with youth. Despite parental guidance and even participation, ultimately this was music for and by youth.

Perhaps the most significant song from this period and one of the only original tunes actually recorded was "I'm No Rebel" (Yo no soy un rebelde) by Jesús ("Chucho") González of Los Locos del Ritmo. By directly referencing the public furor over rebeldismo, the song encapsulated the controversy over delinquency while promoting native rocanrol as a defining vehicle for youth:

|

Not only did the song incorporate the imagery of rebellion, but its use of certain street slang—jalón, melenas, vacilar —directly commercialized a grammar of youth rebellion as well. The song, of course, was an exception, though an important one. As the novelist José Agustín would later comment, it became a "quasi-hymn among youth."[90]

In general, however, lyric content was largely devoid of generational conflict. All the same, the songs were belted out with the same rhythmic

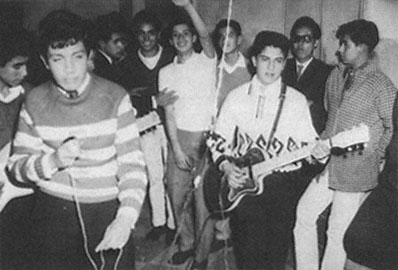

Figure 5.

Scores of Mexican bands emerged by the early 1960s to meet the de-

mand for rocanrol, as in this unidentified photograph, probably taken at a private

party. Source: "Concentrados: sobre 2206, 'Rock and Roll,' n.d.," Hermanos Mayo

Photo Archive, Archivo General de la Nación. Used by permission.

ferocity of their imported originals (see Figure 5). It was rock 'n' roll, after all, and the emphasis was on playing it at the highest possible volume. Describing conflicts with her parents over playing the music at home, one informant recalls: "There always arrived a point when your parents told you to turn it off. Not for the lyrics, which were in Spanish, but because of the noise. That was the [only] problem we really had. It's not that your parents were shocked by the lyrics, like they are today, but more because of the scandal the noise created. For them it was something new, because none of the music from their era was so noisy as rock 'n' roll."[91] Of course, it was not just the noise that was problematic. Rocanrol, despite its domestication, still implied a disruption of social control for many adults. This was especially true, for example, when it was introduced into social spaces marked by traditional hierarchies. In one anecdote, an informant recalls what happened when a group of students brought a recording to their secondary school:

Being a good girl from an intellectual and traditional family, I was a very good student, very well behaved. All of the teachers loved me. And one day I was with a group of girlfriends studying and they put on

a tape. I guess one of them had parents who had brought them a tape player from who knows where—that was quite extraordinary for a kid of that age to have a tape recorder—and she brought it to school and put on a cassette of Mexican rocanrol. Suddenly the director of the school chanced to pass by and it became a huge deal. She reacted so sharply, so irrationally, it was as if she had caught us taking drugs or something. She called our parents and made a big scandal. She even mentioned in at the school assembly.[92]

Nor were other socially sanctified spaces immune to the rocanrol invasion. For example, concerns of an older generation were also reflected in criticism of the transformation of the posadas, a traditional religious celebration held for nine days leading up to Christmas. A communal reenactment of the biblical story of Joseph and Mary's quest for shelter, the posadas had a long cultural heritage in Mexico and were a focal point for community celebration. Each night members of the community piden posada (ask for shelter) from their neighbors in a ritual of call-and-response singing. Gathering in numbers after being "turned away" by each household, the wandering choir finally receives posada, which culminates in the breaking of a piñata and a night of festivities. But these festivities were not isolated from the new youth culture, which began to introduce its own set of values to the event. One writer's reaction to this transformation provides a sense of the contradictions experienced by an older generation that both embraced the country's modernization process and yet felt threatened by the implications of such change. "We don't want to fall into the opinion that all that belongs to past epochs is better than the present," the author began. "The customs and systems are changing and we believe that today life is more practical and comfortable." He continued: "However, it is regrettable that certain customs, deeply rooted in tradition, are transforming, are changing radically and are losing their form and spirit unnecessarily.... Today the 'posadas' only retain a superfluous aspect—the adornments, wreaths, Nochebuena [poinsettia], colored lights—and are converted into carousals, with 'aggressive' dancing and swinging legs and hips in the 'twist,' without anyone recalling the original and genuine spirit of these traditional fiestas." In an accompanying photograph showing a young couple dancing together, contrabass and drumset in the background, the text reads: "The 'posadas' that are organized today by young people do not have any of the traditional characteristics and end in 'twist' exhibitions and other contortions of the modern dances."[93] The permeation of a religious festivity by rock 'n' roll thus suggested the ways in which the youth culture had begun to transform traditional cultural relations at an everyday level.

Another important social space for rocanrol were private parties at home, which acquired the name tardeadas from the word for afternoon . Following the midday meal, which in Mexico is an important family function, youth had the late-afternoon hours to dispose of their leisure time as they pleased, as long as parents approved (or were eluded). Hopefully, someone offered his or her home for the gathering. Even in the more conservative homes, youth discovered ways of being daring, such as one woman's description of tardeadas that took place in her own home: "My [older] sister formed a neighborhood 'club' and even made up club IDs. They organized various games centered around dancing. One was a 'strip game' [juego de prendas ], where you throw the dice or spin a plate ... and if you lose you throw in a watch or a ring, something. And then you danced what the group says. Like, "Imitate Elvis Presley," and so [the losers] had to do it."[94] Taking off one's clothes (as shown in a juego de prendas in the movie Juventud desenfrenada ) would have passed the boundaries of respect; squirming around like Elvis was bold enough. Under the watchful eye of parents, these parties stayed far within the boundaries of excess. As another informant described the tardeada, "It was a youth get-together exclusively to listen to music and, of course, to dance. No one even considered drinking alcohol at that time. It was unheard of that a party got out of hand."[95] However, for women, especially, even these parties could be deemed off limits by anxious parents. As the first informant continued, "But my family was so traditional that I wasn't able to participate much in that either. I just didn't have permission to go to such things. Imagine, [these parties] brought men and women dancing together!"

Rocanrol as a musical style had infiltrated popular culture at various levels, appearing, for example, at birthday parties and even quince años (a coming-out-to-society celebration for girls turning fifteen). Yet while many parents may have accepted the rhythm itself, the fashion statements that accompanied it revealed the underlying conflicts between the generations. As Conchita Cervantes recalls,

You know, for example, the way of dressing was very difficult for my parents to accept. That guys would arrive at a party without a tie or without a jacket, for instance. That was a big problem in my home: that the neighborhood kids arrived in pullover sweaters and tight pants, styles of the rock 'n' roll culture.... I remember my father even chasing boys from my home because they did not arrive in a tie at our birthday parties. If it was an informal party, they could come in a shirt and sweater, but if it was a more formal party then everyone had to come in a tie. No one entered in a regular jacket, none of that.[96]

Thus rocanrol may not have been subversive of buenas costumbres on the face of it, but in its usage it became a wedge against the dictates of parents and other voices of authority.

Actual performance spaces for live rocanrol ranged from organized concerts for the public, to private parties, hotel nightclubs, and the numerous cafés cantantes that began to dot the capital landscape. But other than Bill Haley at the start of the decade, few foreign performers actually appeared during this period. In 1962 reports again circulated that Elvis Presley would be coming to Mexico City, a rumor that proved to be untrue.[97] When Frankie Avalon appeared in 1965, the audience became so enthusiastic that Variety would afterward call the resulting chaos a "riot."[98] In fact, keeping the crowds away from local rocanroleros was sometimes trouble enough. At a performance in Puebla for César Costa, former leader of the Black Jeans, police reportedly resorted to throwing photographs of the artist into the crowd to avoid a melee.[99] Yet commercial sponsorship of bands led to tours throughout the republic (and in certain cases beyond), where artists performed in concert halls, cinemas, and even bullfighting rings. One of the more important sponsorship tours was organized by the Corona Beer Company, which joined together bands and solo artists from various record companies. Ranchera performers thus shared the stage with younger stars, although the rocanroleros were distinguished by their separate travel accommodations: the "Camión a go-go" (Go-Go Bus).[100] Record companies also organized musical competitions in conjunction with radio and television stations, which attracted listeners and viewers with trophies for contestants and giveaways for audiences.[101]

But the most significant social spaces that merged around rocanrol were the cafés cantantes, also identified as cafés existencialistas and cafés a go-go. These places served as focal points for youth reunions, and, both in practice and in representation on film, they came to have a mixed reputation. While they varied in size and category, ranging from fancier nightspots such as the Chamonix, which served upper-class youth in Polanco, to danker holes such as the Sótano (Basement), which catered more to the middle classes, all featured live music (frequently by the same bands) playing songs from the hit charts. These were not clubs in the traditional sense: no alcohol was served, and generally they were not for dancing. Rather, they provided an escape for youth from the watchful eyes and ears of adults, organized around the language of rock 'n" roll: "The atmosphere conformed somewhat to the notion of rock itself, in that there was a rejection of the established norms. For example, back then the seats and tables were really low. The lighting was very, very dim.... In general, basically

one went to those places to get picked up, or to go there with your date and have a good time. There in the darkness nobody knew who was who and so it was really comfortable."[102] In films from this early period, the cafés are depicted variously as modern nightspots (in La edad de la violencia a Picasso painting hangs on the wall) or shady hangouts (as in Juventud sin ley ) and were generally associated with malevolent deeds. Later films sought to adjust this image, as in Twist, la locura de la juventud , where the well-lit café doubles as an ice-cream parlor. Johnny Laboriel, who performed in numerous clubs with Los Rebeldes del Rock during this period, argues that prior to 1965 an atmosphere of "healthy entertainment" unmarred by drugs or alcohol prevailed.[103] If this was the atmosphere on the whole, it did not stop police harassment, and in 1963 many of the cafés were shut down on the pretext that they fomented criminal activities.[104] Moreover, parents looked with concern on such unsupervised social spaces, and with the shift from rock 'n' roll to the more irreverent style of rock performance around 1965, these clubs faced even greater repression.

A Hegemonic Arrangement

The containment of rock 'n' roll during the early 1960s was part of a broader movement of self-policing the boundaries of media representation. Such efforts to "clean up" the representation of modern Mexico did not originate with agents of the media, but, under the pressure of conservative watchdog groups and the 1960 law regulating broadcasting, every effort was made to demonstrate a willingness to conform rather than provoke. Thus in July 1963 the National Chamber of Broadcasting Industries addressed a letter to President López Mateos reaffirming its commitment to "elevate the cultural, civic, and social level of our transmissions in order to comply faithfully with the social function which the law requires."[105] The letter prefaced an agreement drawn up between the chamber and various advertising and commercial interest groups to "autolimit ourselves ... in the production of radio and television soap operas, as well as other ethical and moral norms that should be observed by the people who directly or indirectly participate in the transmission of radio and television." The origins of the pact were an explicit response to what the letter alluded to as an "impending threat ... derived from a definitive current" of conservative media watchdogs, such as the Mexican League of Decency. This "current" was continuing to accuse the radio and television industry of "transmitting themes which offend morality and family values" and thus not complying strictly with the Radio and Television Law of 1960.

The new pact in actuality simply reaffirmed many of the basic provisions established in the 1960 law (see chapter 1). For example, in terms of language any "impudent, obscene expressions [and] sentences using double-meaning" were to be eliminated. With regard to the image of "matrimony, family [and] home," it was agreed to "maintain a consistent practice with respect to matrimony as the fundamental [element] of the family, the home and society." Suicide would be "proscribed as a solution to any problem." Significantly, music and dance received special mention. To be eliminated were "transmissions of every musical selection whose lyrics might offend even the most open-minded persons." The censorship of music underscored the broadcasters' commitment "to orient the transmissions in a way that complies wholly with their social function as cooperating with the resolution of problems in Mexico, fortifying democratic convictions, national characteristics, cultures and traditions of the country, and combating the influence of ideologies which undermine and are contrary to our Institutions." Also covered by the pact was the self-censorship of "imprudent and lewd attitudes and scenes [on television] taking special care with dances," a reference to the often risqué shots in youth films of underage females' legs and undergarments when dancing. "All 'close ups' or 'takes' that concentrate attention in a way that is intentional and improper will be eliminated," the pact stated plainly.

This document suggests several things. For one, it reflected an attempt by commercial interests to fortify their position in the face of continued attacks against them by conservative interests. Second, it suggested the ineffectualness of the federal government in enforcing the 1960 law, since the pact largely repeated, though in greater detail, the same themes covered by the earlier law. Third, it underscored the importance the broadcasting industry placed on not wanting to create problems with the government over media content. By expressing directly to the president their intentions to "comply faithfully with the social function" assigned to them by law, broadcasting interests sought to preempt any excuse for broader censorship by the regime. The larger picture that thus emerges is a hegemonic arrangement between the ruling regime and the major figures of the mass media in which the latter operated under relative autonomy in exchange for a policy of self-censorship. It was under these conditions that a contained youth culture was successfully commercialized for the first half of the 1960s. However, as the logic of this movement later changed—as psychedelia emerged as the leit motif of the youth culture abroad—the cultural industries would find themselves constrained by a hegemonic arrangement that restricted commercializing new gestures of rebellion.

Nonetheless this was rocanrol's Grand Era, a term used to this day. While several of these bands continued to perform throughout much of the 1960s, around 1963 the record companies found that steering star performers away from group efforts and into the modern baladista (romantic soloists) style then emerging in vogue internationally (led by artists such as Paul Anka and Connie Francis) was both more manageable and equally, if not more, profitable. Johnny Laboriel was an exception to this (remaining faithful to his Rebeldes del Rock), but César Costa of the Black Jeans and Enrique Guzmán of Los Teen Tops joined the ranks of female performers Julissa and Angélica María to begin solo careers. "The end result," writes Roura, "was a ballad that was less perturbing, less committed, more tranquilizing"[106] than music with a backbeat.

Spanish-language rocanrol had been promoted by commercial interests and adopted by mainstream society as a metaphor for modernity: an exuberant, nonthreatening vehicle for the expression of liberalism and leisure consumption. Indeed, in the aftermath of the 1958 student and union conflicts, rocanrol appeared as a convenient distraction for youth, one purged of its direct ties and associations with rebeldismo. Repackaged as a product of the modernizing Revolution, Mexican rocanrol and the baladista style that followed were proffered by the cultural industries as the embodiment of familial harmony and social progress, a medium for improved communications between the generations and a moderator of youthful restlessness. Containing this image, however, proved increasingly precarious after mid-decade. With the arrival of the Beatles and the new wave of British (and in turn, U.S.) bands that they heralded, rock 'n' roll shed whatever lingering charm it once retained for adults and became simply rock. With the resultant change in musical expression came renewed fears of youth disorderliness and the coincident reality of political crisis.

The interests responsible for producing and distributing native rocanrol were keenly aware of conservative and xenophobic currents in Mexican society and thus sought to avoid provoking a possible backlash by presenting a contained version of the youth culture. This version glossed over themes of juvenile delinquency and social alienation to present an image of youth as the modernizing agents in a society of benign paternalism. Via the promotion of a native rocanrol movement a different self-image of Mexico, one that contrasted with the stereotyped vision of campesinos sleeping lazily under their sombreros, emerged. Thus bilingual liner notes from an album by Los Rebeldes del Rock not only indicated the group's marketing in the Anglo world but also highlighted the transformed image of Mexico that the industry and the band hoped to project: "Music is the and [sic ] result of

the animated status of the multitudes[.] Musically we have liverd [sic ] several cycles, the Waltz, the Charleston, the Swing, the Fox-trot, the Boogie-boogie [sic ], etc.; leading todays [sic ] modern craze[,] the product of youths [sic ] search for new horizons in music—Rock! Rock 'n' Roll, authentic symbol of modern youth, represents their anxieties in a new musical sense with which they have not only revolutionized rythm [sic ] but also musical techniques. This current has also affected Mexico."[107] The global tours by groups such as Los Locos del Ritmo and Los Loud Jets (known as The Mexican Jets abroad) underscored for Mexican society, if perhaps less so for the world at large, the transformation of Mexico from a Third World nation targeted for consumption to an exporter of global popular culture. Appearing in a photograph at the 1964 World's Fair in New York City, the Mexican Jets came to represent the cosmopolitan aspirations of the country's elite and middle classes alike.[108] As long as the record companies and television producers had virtually complete control over the musicians' recorded performances, the transmitted image of rocanrol was closely cropped for any gestures of defiance that might violate the established norms—and laws—governing the representation of youth, family, and nation. Thus for Víctor Roura, this period was characterized by nothing less than a "simulated rebellion"[109] that served the interests of an older generation as much as it did the young. However, in spite of its circumscription by the media, the movement had a profound impact on society. Containing the strategies of consumption of this music—its relationship to the transformation of cultural values and its spatial conquests—was a less tenable proposition.