Natural History

Some fifty million years ago, the Pacific Northwest had a tropical climate. At that time, the landmass that later became the Willamette Valley lay completely submerged under the warm waters of the Pacific Ocean, whose tides lapped at the base of the ancient western Cascade Mountains. Roughly thirty million years ago, the ocean's waters began to subside to the west as huge basalt flows and folding and faulting uplifted new mountains, the Coast Range, from the floor of the Pacific.

The submerged Willamette Valley now lay between two mountain chains, acting as a catch basin for eroding sediment. During the next twenty-five million years, the Willamette Valley landmass slowly rose, the inland sea that covered it drained, and the present river valleys formed (map 1).[3]

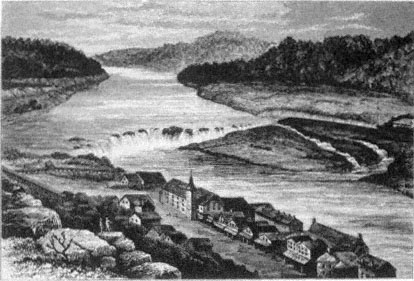

About ten million years ago, basalt lava flowed and solidified across the northern outlet to the valley. The relatively modest flow of the Willamette River has been unable to breach this impediment, and thus over the millennia rich river alluvia of clay, silt, sand, and gravel collected behind it in the huge trough that is now the Willamette Valley. The ancient basalt flow forms a cliff over which the Willamette River plunges some fifty feet (figure 2).[4]

Roughly one million years ago, the earth's surface cooled, creating in North America a continental ice sheet that spread southward from the Arctic zone into the northernmost reaches of the Pacific Northwest. In high mountainous zones of the region, such as in the Cascades east of the Willamette, large alpine glaciers formed. Although these glaciers did not descend to the Willamette Valley lowlands, streams issuing from them carried yet more sediment down to the valley. At the end of this cool cycle, glaciers and the continental ice sheet retreated, releasing huge quantities of water and inundating the entire Willamette Valley with inland seas up to one hundred feet deep. By the time of the next glacial advance some sixty thousand years ago, however, the Willamette had once again been drained of its waters.[5]

During this next ice age, the advancing continental glacier dammed a fork of the Columbia River far to the northeast of the Willamette Valley, in what is now northeastern Washington and northern Idaho. Behind it formed a large lake. Several times as this ice sheet retreated, weakened, and broke before forming again, huge floods swept down the Columbia River. Because precipitous banks restricted the Columbia's flow downstream from its confluence with the Willamette River, floodwater carrying chunks of glacial ice washed all the way back to the southern portion of the Willamette Valley. Each time floodwater backed up into the Willamette, it destroyed the natural vegetation and deposited huge amounts of silt and even some large boulders.[6]

While the land was still marshy, only slowly draining from this cycle of flooding, a warming and drying period in the climate encouraged the growth of tree species such as Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii ), Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis ), and western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla ) in

Map 1.

The Willamette Valley.

Figure 2.

Willamette Falls, 1878. Source: Wallis Nash, Oregon: There and Back in 1877 .

higher areas and along the edges of the Willamette Valley. On the well-drained foothills surrounding the valley grew grand fir (Abies grandis ) and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa ).[7]

Beginning about eleven thousand years ago and continuing until about four thousand years ago, the Northwest's climate became yet drier and warmer. During this period, marshlands and lakes on the Willamette Valley's floor receded farther, more grasses appeared, and the more drought-tolerant western white oak (Quercus garryana ) and California black oak (Quercus kelloggii ) became the dominant tree species. Today, western white oak naturally occurs from Vancouver Island south into California's central valleys, and thus grows throughout the Willamette. The California black oak's range, however, extends only as far north as the very southern portion of the Willamette Valley. It does not occur naturally north of there.[8]

About six thousand years ago, the valley became dry enough to inhabit, and humans descended to the valley floor from the surrounding hills, which they had occupied for at least two thousand and possibly as much as four thousand years.[9] Although these people did not know it,

their very act of moving from foothills to valley floor revealed a tension between human occupation and the natural features of the Willamette's landscape. Recognizing this tension, especially with regard to the role of foothills and valley floor, is central for understanding the life and thought of nineteenth-century Euro-American settlers.

Two thousand years after humans arrived on the Willamette's floor, the climate again changed, initiating a cooler and moister pattern that has persisted up through and beyond the arrival of Europeans in the Pacific Northwest at the end of the eighteenth century. This climatological pattern has continued to the present, though indications are that the Willamette Valley, like much of the West, is entering another drying and warming period. During the last four thousand years, a strong marine influence has marked the region's climate. Winters are especially wet, though coastal mountains to the west protect the valley from severe winds and driving rains that blow in from the ocean. Storms coming in off the Pacific drop much of their precipitation as they pass over the coastal chain. The valley, left with gentle yet persistent rains that fall from mid autumn to late spring, receives as little as thirty inches of rain on the Coast Range's eastern slopes, but as much as sixty inches along valleys such as the Calapooia that reach back into the foothills of the Cascade mountains on the eastern margin of the Willamette. As the warm, wet winter winds push up the high Cascades, they cool and drop their remaining moisture as rain and snow in annual amounts of up to 120 inches. The Cascades also act as a cordon against the dry, frigid continental winds that influence the winter over much of the North American landmass to the east of the Willamette. This barrier, coupled with the Pacific's warm winter storms, keeps valley temperatures moderate in winter, with a mean of forty degrees Fahrenheit during the coldest months. Snow does occasionally fall on the valley floor, though it rarely lingers. The predominantly southwest winter winds off the Pacific shift to the north in late spring, bringing a drier and warmer period when little if any precipitation falls and the mean temperature reaches sixty-seven, with occasional hot spells resulting in daily temperatures of over one hundred. This pattern continues until the rainy season begins again in mid autumn.[10]

Precipitation falling on the Willamette's bordering foothills and mountains eventually finds its way to the valley floor, whose great expanse slopes gently, almost imperceptibly to the north. Native Americans and early European settlers witnessed how the absence of relief in

the Willamette Valley forced streams, creeks, and rivers, after breaking out of the foothills, to meander sluggishly across the valley in a series of braided channels, oxbows, sloughs, and sandbars, depositing their sediments on banks that rose slightly above the surrounding plain. Choked with debris, vegetation, and mud islands, streams and rivers of the Willamette often overflowed onto nearby flood plains, leaving standing water for many months of the year. Lack of relief and drainage, coupled with occasional winter snows in the valley and foothills that melt quickly, caused major floods at least every tenth season, sometimes as often as every fifth season during prehistoric times.[11]

This moderate, seasonally moist climate, along with the marshy conditions that have characterized the Willamette Valley for four thousand years, has in large part determined the flora that grow there and that greeted the earliest Euro-American settlers. These first settlers found along the Willamette River and its tributaries on the flat valley floor extensive gallery forests—often up to two miles wide—composed of Oregon ash (Fraxinus latifolia ), cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa ), willows (Salix spp.), red alder (Alnus rubra ), and bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum ), with Douglas fir and western red cedar (Thuja plicata ) sprinkled throughout. Along smaller streams such as the Calapooia, the gallery forests narrowed. Along the foothills of the Willamette Valley flourished Douglas fir, grand fir, ponderosa pine, and incense cedar (Calocedrus decurrens ), with western hemlock and western red cedar thriving in moister and cooler yet well-drained areas along upper foothills and streams. Hardwood trees such as bigleaf maple, western white oak, and madrone (Arbutus menziesii ) also grew in the foothills. Their understory consisted of shrubs such as hazelnut (Corylus cornuta ), ocean spray (Holodiscus discolor ), and snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus ), and along prairie edges, smaller plants such as cheat grass (Bromus vulgaris ), Oregon grape (Mahonia nervosa ), and tarweed (Madia spp.). Between the foothills and the gallery forests of the Willamette Valley grew extensive meadows composed mostly of grasses, flowers, and scattered oak trees, or oak savanna.[12]

Ecologists apply the term climax to the theoretically highest stage of ecological succession, or evolution, of a plant-animal community or ecosystem. At climax, the ecosystem is stable and self-perpetuating. Climax does occur in nature, but other natural factors, such as disease and fire, limit the stability, persistence, and extensiveness of a climax community. Had the Willamette Valley been left to "nature," its gal-

lery and foothill forests of maple, Douglas fir, and grand fir would theoretically have eventually covered the valley floor as a climax community. However, the Native American inhabitants of the Willamette, in order to ensure an abundance of the plants and animals essential to their diet and culture, used fire to keep the valley's flora in a fire-maintained subclimax state of grasslands and oak groves for hundreds of years.[13]