Five—

The "Achieve" and "Mastery":

Hopkins's Poetry

Duns Scotus's Oxford

Towery city and branchy between towers;

Cuckoo-echoing, bell-swarmèd, lark-charmèd,

rook-racked, river-rounded;

The dapple-eared lily below thee; that country and town did

Once encounter in, here coped and poisèd powers;

Thou hast a base and brickish skirt there, sours

That neighbour-nature thy grey beauty is grounded

Best in; graceless growth, thou hast confounded

Rural rural keeping—folk, flocks, and flowers.

Yet ah! this air I gather and I release

He lived on; these weeds and waters, these walls are

what

He haunted who of all men most sways my spirits to

peace;

Of realty the rarest-veinèd unraveller; a not

Rivalled insight, be rival Italy or Greece;

Who fired France for Mary without spot.

(Poem 44)

Neither the syntax nor the diction of "Duns Scotus's Oxford" is difficult, and the sense, therefore, of the poem is easily accessible. The poem suspends its mood between celebration and lament. The celebration is for Duns Scotus himself and an Oxford which retains and triggers memory of him, and the lament is for the gracefulness of the past, a past still at the heartfelt center of Oxford. But

the lament, nostalgic as it may be, is oddly submerged in the celebration; and when it surfaces, it is transformed into something harsher, not a loss per se but more a criticism of a modern Oxford which defies the harmony between city and country, a harmony of old. The poem then venerates memory, memory whose power and energy render her more immediate than the actual baseness of nineteenth-century Oxford.

The value system is rendered through metaphor—predominantly architectural and natural—through rhyme and rhythm: when nature and architecture are integrated, Oxford is celebrated; when they are at odds, an Oxford of the past is longed for. The opening stanza describes the city, but—as one finds out only in the subsequent stanza—only the city center, what comes to be its essence.

Towery city and branchy between towers;

Cuckoo-echoing, bell-swarmèd, lark-charmèd,

rook-racked, river-rounded;

The dapple-eared lily below thee; that country and

town did

Once encounter in, here coped and poisèd powers;

The opening line establishes the condition of harmony, that architecture be natural and nature be architectural. Towers frame the view, opening and closing the verse line and receiving its stresses; "branchy" and "towery" so go together, by virtue of rhyme and placement, that trees and towers seem to share each other's qualities, together a woven or patterned interlacing network. While the first image, "towery city," seems to establish the foreground of our visual field, Hopkins throws the background—"branchy between towers"—also to the fore, as if harmony requires and depends on a frontality of

forms which are reciprocally architectural and natural ("towery" and "branchy"), equal in importance to each other. The exchangeability, even confusion, of forms is rendered complete in the next line, in which bells and birds occupy the other's roost, take on the other's sound; and we almost have the sense that the "dapple-eared lily" hears them. "Coped" may be architectural and ecclesiastical, "poised" an abstract quality and a mechanical one, too. The contrasting present-day Oxford is the brickish Victorian Oxford whose shapeless suburbs extend into nature and defy harmony: base and brickish appear the harsher juxtaposed with towers, powers, flowers , with weeds, waters, walls . The stress we feel, rhymed and constructive, is in the gathering and releasing, in breathing; and harmony almost seems linked to and like that natural process. Mental peace, like architectural harmony, also requires and results from an integration of weeds, waters, and walls; "insight," the special quality which Hopkins selects to distinguish Duns Scotus, constitutes a pun on visual perception, suggesting that the ability to integrate the natural with the man-made, the religious with the organic, Oxford as city with Oxford as country, is a quality rare and worthy. At once visual perception becomes a moral and religious act, one which the poem supports.

While "Duns Scotus's Oxford" seems to build from city to man, from image to action, "Spelt from Sibyl's Leaves" seems to unbuild.

Spelt from Sibyl's Leaves

Earnest, earthless, equal, attuneable, | vaulty, voluminous,

. . . stupendous

Evening strains to be tíme's vást, | womb-of-all, home-of-all,

hearse-of-all night.

Her fond yellow hornlight wound to the west, | her wild

hollow hoarlight hung to the height

Waste; her earliest stars, earlstars, | stárs principal, overbend

us,

Fíre-féaturing heaven. For earth | her being has unbound; her

dapple is at an end, as-

tray or aswarm, all throughther, in throngs; | self ín self

steepèd and páshed—qúite

Disremembering, dísmémbering | áll now. Heart, you round

me right

With: Óur évening is over us; óur night | whélms, whélms,

ánd will end us.

Only the beakleaved boughs dragonish | damask the tool-

smooth bleak light; black,

Ever so black on it. Óur tale, O óur oracle! | Lét life, wáned,

ah lét life wind

Off hér once skéined stained véined varíety | upon, áll on twó

spools; párt, pen, páck

Now her áll in twó flocks, twó folds—black, white; | right,

wrong; reckon but, reck but, mind

But thése two; wáre of a wórld where bút these | twó tell, each

off the óther; of a rack

Where, selfwrung, selfstrung, sheathe- and shelterless, |

thóughts agaínst thoughts ín groans grínd. (Poem 61)

Unlike "Duns Scotus's Oxford," where evocation of Scotus himself is linked to city and to air preserved almost hermetically, in "Spelt from Sibyl's Leaves" there is no such evocation of the past but rather a "disremembering," appropriate, as we will see, to the unbuilding, the "dismembering" in the poem.

For earth | her being has unbound; her

dapple is at an end, as-

tray or aswarm, all throughther, in throngs; | self ín self

steepèd and páshed—qúite

Disremembering, dísmémbering | áll now.

20

Earnest, earthless, equal, attunable, | vaulty,

voluminous, . . . stupendous

Spelt from Sibyl's Leaves

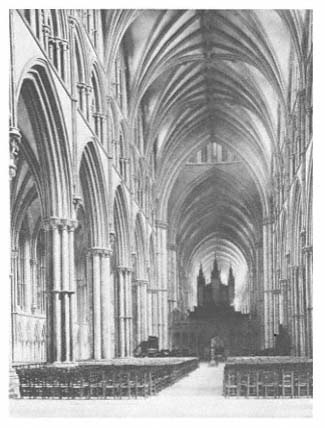

Here in the Lincoln Cathedral we see the hollow

center, the building space of literary architecture

as an art of rhythmed enclosure.

Nature does engender: Sibyl's leaves spell and spill, a proliferation verbal, cognition depending upon verbalization; and in a circular way, it is a cognition of that very proliferation. Does wording render idea concrete, accessible? Does nature, not man, spell—that is, word—and make concepts apprehensible?

The first long stanza of "Spelt from Sibyl's Leaves" opens with the struggle for description and definition of something not concrete: space. If Hopkins cannot define it by activating it or filling it—as in "branchy between towers," "branchy" giving substance to "between" in "Duns Scotus's Oxford"—he does so by enclosure: space may be defined as "content" if something else gives it peripheries and appropriate shape; something may be empty if it is enclosed:

Earnest, earthless, equal, attuneable, | vaulty, voluminous,

. . . stupendous

Evening strains to be tíme's vást, | womb-of-all, home-of-all,

hearse-of-all night.

The first adjectives seem beyond physical rendering; but "vaulty" gives extension, cathedral shape; "voluminous" gives mass, weight. Similarly, birth, life, and death are rendered in images also of enclosure, images again suggesting contents and outside limits; definition, verbally sought, of what is abstract and conceptual is in fact accomplished by physical delineation which is implicitly architectural, having spatial dimension, weight, and size. So, too, the movement of the poem seems to involve a locating or placing of ideas made substantial: light may be "wound," thread-like, or "hung"; it has dimensions, position, so that nature, tortured on Judgment Day, is some oddly cathedral-like structure, built, demolished

and rebuilt again within the life-span of the poem. Images of roundness run through the first stanza: "wound," "overbend," "round"; and the emotion in response to the event is rendered, potentially at least, in the terms or shape of the event itself, "Óur évening is over us; óur night | whélms, whélms / ánd will end us." "Whelming," as something partial, attracts its natural partner "over"; and our emotion, "overwhelming" takes on the literalness of enclosure. Evening seems to move literally, mechanically, into night. And structuring seems to be remembering, "spooling" in contrast to the unstructuring or architectural "dismembering" and "disremembering." Nature acts on what is man-made, on definition or "thinging," on light which is "tool-smooth":

Only the beakleaved boughs dragonish | damask the tool-

smooth bleak light; black,

Ever so black on it. Óur tale, O óur oracle!

If definition is a way of rendering and making accessible what is abstract, so, too, is winding a kind of organizing what is random and disordered. The poem's end seems enclosureless: the Last Judgment, what amounts to "undoing," is imaged by the absence of peripheries, night being no longer a "hearse" but now "sheatheless" and "shelterless." That final night cannot be enclosed or have perceptual limits suggests that it cannot therefore be grasped, worded, or defined. Instead, we have an image of sacrifice on a torture rack, but no saint, not even Christ, is being tortured: "self" is. And, crucially, "self" is defined, figured forth, "selved," as thought substantialized or concretized. Hopkins, though, goes still further: even torture is, in a sense,

potentially generative. In the poem's end, thought retains its substance and, therefore, its mechanical capabilities: "thóughts agaínst thoughts ín groans grínd" as if thoughts have weight, direction, position. [Plate 18] And grinding, while a wearing down, also suggests a productive and generative friction: metaphor pruned, worn down, shaped, releases the intellectual and poetic energy of probing, defining, rendering or transposing. In this way, the end of the poem is almost affirmative: thoughts have taken on the architectural, physical characteristics that syllables had in Hopkins's "Rhythm and other structural parts," and we have the sense that although all else may be destroyed in the end, the artist, perhaps Hopkins as artist, can create poems so long as thoughts can generate other thoughts, syllables other syllables, poems other poems.

Some of Hopkins's poetic terms, such as pitch and stress , are both musical and architectural, and as much may be said of the images in "Spelt from Sibyl's Leaves" and in another poem, "On a Piece of Music."

(On a Piece of Music)

HOW all's to one thing wrought!

The members, how they sit!

O what a tune the thought

Must be that fancied it.

Nor angel insight can

Learn how the heart is hence:

Since all the make of man

Is law's indifference.

[Who shaped these walls has shewn

The music of his mind,

Made known, though thick through stone

What beauty beat behind.]

Not free in this because

His powers seemed free to play:

He swept what scope he was

To sweep and must obey.

Though down his being's bent

Like air he changed in choice,

That was an instrument

Which overvaulted voice.

What makes the man and what

The man within that makes:

Ask whom he serves or not

Serves and what side he takes.

For good grows wild and wide,

Has shades, is nowhere none;

But right must seek a side

And choose for chieftain one.

Therefore this masterhood,

This piece of perfect song,

This fault-not-found-with good

Is neither right nor wrong,

No more than red and blue,

No more than Re and Mi,

Or sweet the golden glue

That's built for by the bee.

[Who built these walls made known

The music of his mind,

Yet here he has but shewn

His ruder-rounded rind.

His brightest blooms lie there unblown,

His sweetest nectar hides behind.]

(Poem 148)

Here the same concretizing takes place that occurred in the other poems; and "mind" itself looms an architectural structure such that inside and out seem to define self and not-self:

Who shaped these walls has shewn

The music of his mind,

Made known, though thick through stone

What beauty beat behind.

So, too, definitions of values, aesthetic and ethical, hinge on an architectural image. Harmony, or discord for that matter—the mind's character and the artist's—are revealed by an architectural analogue, the artifact or structure, either as mind or as product.

What makes the man and what

The man within that makes:

Ask whom he serves or not

Serves and what side he takes.

It is not surprising if, on reflection, the mind as structure, so imaged in "On a Piece of Music," makes us think that God's mind, gigantic yet structural or architectural, was also figured forth in "Spelt from Sibyl's Leaves," a mind extending into nature the way God's mind does in "The Wreck of the Deutschland." Just so, order in "On a Piece of Music" is imaged by architectural members, and that order testifies to divine or ethical control:

How all's to one thing wrought!

The members, how they sit!

O what a tune the thought

Must be that fancied it.

We may well recall Robert Browning's "Abt Vogler" where, in the same way, music takes the form of a piece of architecture; but for Hopkins, the artifact, not only as an extension of the artist, but as an emblem of him, is imaged by construction. We sense both an internal and an external pressure, man shaped and shaping; and "what

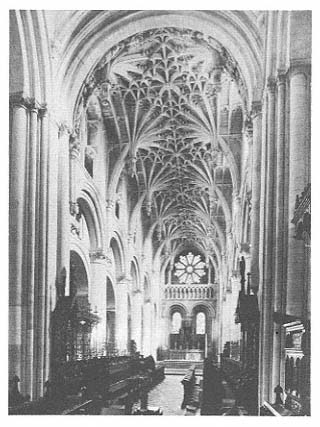

21

How all's to one thing wrought

The members, how they sit!

O what a tune the thought

Must be that fancied it.

On a Piece of Music

(Wells Cathedral: Nave Looking West)

side he takes" assumes a literalness of actual position. By contrast, that over which the artist exerts no control is imaged as organic growth, defined not as the tree-steepled Oxford was but as was modern Oxford and her shapeless suburbs.

For good grows wild and wide,

Has shades, is nowhere none;

But right must seek a side

And choose for chieftain one.

Architecture may embody nature, but more important, it should offer structure to nature, not miming a structure-less opulence and variety. [Plate 22] Here again Hopkins's value system reminds us of that in his schoolboy poem, "The Escorial," in which poet-architect rejects Gothic forms with their "engemming rays," their "foliag'd crownals" all "in a maze of finish'd diapers" (Poem 1) of a nature untended. We also have the sense that, for Hopkins, structure protects; while soul may be imaged organically, as flower, as nectar, the creating and created mind walls it in, over-bending the flower of soul or idea, that it be safe from destruction.

Who built these walls made known

The music of his mind,

Yet here he has but shewn

His ruder-rounded rind.

His brightest blooms lie there unblown,

His sweetest nectar hides behind.

Stress, grind, and density of syllables are notably absent from the neatly mellifluous stanzas of "On a Piece of Music," so that it is more obscure than the strenuously mannered "Sybil's Leaves."

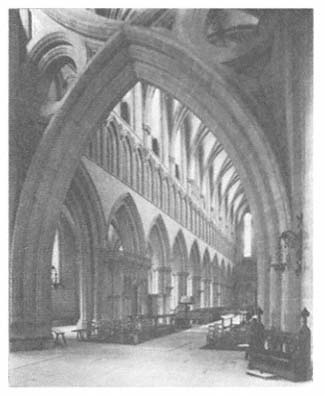

22

Nature vaulted and traced: Oxford Cathedral. Here we can

also see what Ruskin called an elastic tension which

communicates "force from part to part."

It should not surprise us, after looking at these three poems, to find that Hopkins, when doubting his own generative, creating capacity, images that capacity or lack thereof architecturally. In one of his most personally poignant poems, the structure, built from nature, the stuff of nests and twigs, is architecturally laced and fretted:

Oh, the sots and thralls of lust

Do in spare hours more thrive than I that spend,

Sir, life upon thy cause. See, banks and brakes

Now, leavèd how thick! lacèd they are again

With fretty chervil, look, and fresh wind shakes

Them; birds build—but not I build; no, but strain,

Time's eunuch, and not breed one work that wakes

Mine, O thou lord of life, send my roots rain.

(Poem 74)

While the imagery suggests the procreative, it seems more the fathering forth of an artifact-child that Hopkins so desires. The sought-for rain almost suggests a need for growth in order to build, the need for sustenance in order to create rather than sustenance of which the direct product is the artifact. For Hopkins the nest, the structural home for offspring, suggests that poems house ideas, that they are constructed nature monuments; and we have the sense that, for Hopkins, his recasting of nature constitutes a survival or preservation effort. For this purpose, as poetic metaphors, art, science and nature, music, architecture, mechanics and optics, are all potentially compatible. Throughout his oeuvre, Hopkins varies the theme, but for the most part, in all he images construction—whether of body, artifact, created world of human mind—as architectural struc-

ture. Man's body not only houses but grounds, substantiates, his spirit: in "The Caged Skylark," we find both ideas, momentarily perhaps, compatible: potentially, the bird's nest is no prison.

As a dare-gale skylark scanted in a dull cage

Man's mounting spirit in his bone-house, mean house,

dwells—

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Man's spirit will be flesh-bound when found at best,

But uncumberèd: meadow-down is not distressed

For a rainbow footing it nor he for his bónes rísen.

(Poem 39)

So, too, does Hopkins figure mind as structurally limited and delimiting: in "The Lantern out of Doors," he writes,

Death or distance soon consumes them: wind

What most I may eye after, be in at the end

I cannot, and out of sight is out of mind.

Christ minds: Christ's interest, what to avow or amend

There, éyes them, heart wánts, care haúnts,

foot fóllows kínd,

Their ránsom, théir rescue, ánd first, fást, last friénd.

(Poem 40)

Here again, mind is defined by the literal peripheries of perception, distance. We have, in a sense, a double idea, that projection is out of the mind, "out" meaning from out of, generated from inside and projecting out; that which is deduced, understood from sight is also "from" the mind, and sight itself is an act of the mind. To "eye after," to sight—we are prepared for what happens in the poem: the mind is defined by and becomes its own action, and appropriately is transformed from noun into verb.

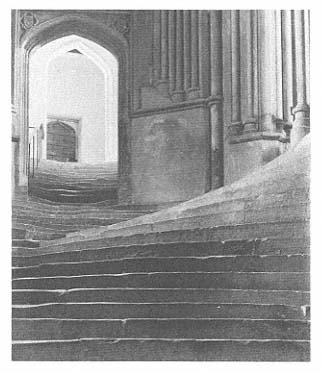

23

Architecture at its softest; it is not for this that Hopkins turns

to architecture. (Compare with Plates 3 and 17, above.) Here the

architecture—its stone stairs—registers transformation from

accurate use. The sea of stairs, while structurally so different

from Hopkins's preferred architectural forms, does suggest

Hopkins's lines on vision—death and distance:

Death or distance soon consumes them: wind

What most I may eye after, be in at the end

I cannot, and out of sight is out of mind.

The Lantern out of Doors

(Wells Cathedral)