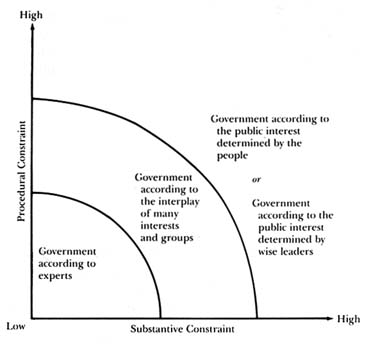

Regions of the Map

Four perspectives on citizen ability have now been translated into a viewpoint on the proper degree of bureaucratic discretion, and each may thus now be located on the map. I will call these perspectives government according to experts, government according to the public interest determined by wise leaders, government according to the public interest determined by the people, and government according to the interplay of many interests and groups. If the map is interpreted as a set of concentric bands starting at the lower left-hand corner, with the farthest band signifying the greatest constraint, then our

[34] Douglas Yates calls this the pluralist logic for bureaucracy (Yates, Bureaucratic Democracy [Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1982], chap. 1). Aberbach, Putnam, and Rockman call it the politics model (Bureaucrats and Politicians , pp. 141–42). Stephen H. Linder similarly finds a rationale for discretion and bargaining in bureaucracies in pluralist thought (Linder, "Administrative Accountability: Administrative Discretion, Accountability, and External Controls," in Scott Greer, Ronald Hedlund, and James L. Gibson, eds., Accountability in Urban Society: Public Agencies Under Fire [Beverly Hills CA: Sage Publications, 1978], pp. 181–96. Vincent Ostrom's model of democratic administration is also premised on dispersion of authority (Ostrom, The Intellectual Crisis in American Public Administration [University AL: University of Alabama Press, 1974]), chap. 4.

[35] Dahl and Lindblom, for example, contend that "no one should suppose that by administrative fiat they can possibly overcome the fundamental lack of coordination inherent in the American political process; and to any person who believes polyarchy is desirable, the solution should be a repugnant one even if it were possible" (Politics, Economics and Welfare , p. 351).

Figure 3. Public Ability and Bureaucratic Constraint

four perspectives take their places as shown in Figure 3. As with most terrains, the topography of democratic control of bureaucracy is not marked by abrupt changes in geology. The bands are not intended to demarcate radical shifts in discretion but rather gradual shadings. Similarly, assumptions about citizen abilities blend at the fringes. Thus, while graphically the bands appear as sharp borders, they are not intended to signify such.[36]

[36] I have described and located what may be thought of as pure positions on the map. Many, of course, may take somewhat less pure stands and think competence varies depending upon the circumstances involved. Some, for example, may think citizens are more competent to judge substantive ends than

procedural issues, or vice versa. These people would alter their preferred location on the map according to the particulars of the circumstances they were considering. I discuss a major of variation in competence—differences among policy areas—in chapter 5.

The bands do, however, represent substantially different normative regions. For those who see the people as competent, the critical question is whether this competence lies in their collective capacity or in the results of their individual and group pursuits of their own wants. If the former, then the outermost band is occupied; if the latter, the central one. For those who do not see the people as competent, the issue becomes how well their elected representatives can fulfill the function of serving the people's interests.[37] The innermost band reflects the position that they cannot; the outermost stands on the assumption that they can very well. In the center, representatives are presumed to be one of many able participants in government decision making.