Chapter One

The Revolutionary Cult of Law

David's drawing The Tennis Court Oath gives little evidence of the controversy that attended the birth of France's first constitution (Plate 1). A swarm of outstretched arms converges on the president of the National Assembly as he leads his colleagues in their pledge of unity. Only one figure, cringing in the lower right corner like an allegory of damnation, refuses to participate. He is Martin Dauch, representative to the Estates-General from the bailiwick of Castelnaudary, who refused to take an oath he felt would compromise his allegiance to the king. His resistance sets in relief the enthusiasm of the patriots, who seem spiritually and physically invigorated as they surrender their will to the national cause. Embodied in David's rigorously choreographed demonstration of unanimity is a cherished revolutionary belief, proclaimed in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen: "Law is the expression of the general will. All citizens have the right to contribute personally, or by their representatives, to its formation."[1]

The revolutionary equation of lawmaking with national sovereignty, persuasively visualized by David, challenged one of the most venerable French monarchic traditions. Prior to the Revolution, the French king was invested with a legislative supremacy articulated by the seventeenth-century theorist of absolutism, Charles Loyseau: "Il n'y a que le Roy seule, qui puisse faire des loys" (Only the King can make laws.)[2] In practice, the absolute monarch's legislative power was limited. It could transgress neither the dictates of religion nor the "fundamental laws of the kingdom," a body of custom and written law that, among other things, prescribed the royal succession, forbade abdication of the throne, and

attributed the power to vote on taxes to the Estates-General.[3] Monarchic legislative power was also limited to the administration of justice and the maintenance of custom.[4] And so arbitrarily was the law executed that "for men of the Old Regime," Alexis de Tocqueville complained, "the place that the idea of law should occupy in the human mind was vacant."[5]

A new perspective on the law opened during the second half of the eighteenth century when the legislator's role in improving human society emerged as a prominent topic in literature.[6] The dialogue On Legislation (1776) by the philosophe Abbé Gabriel Bonnot de Mably (1709-1785) is an example. "Nothing is impossible for a capable legislator," Mably's principal interlocutor maintains; "he holds, so to speak, our hearts and our minds in his hands; he can make new men."[7] Here is a foreshadowing of the optimism with which David's Tennis Court Oath is charged. For those touched by this Enlightenment current, the roles of lawgiver and moral preceptor were indistinguishable. Accordingly, the Encyclopédie emphasized the role of the lawgiver in directing the education of children so as to inspire "humanity, benevolence, public virtues, private virtues, love of honesty, [and] passions useful to the state."[8] The cult of the lawgiver was given especially solemn expression by the author of The Social Contract .[9] Rousseau's fascination with the figure of the lawgiver was informed by a belief that good laws could inculcate virtue.

The legislator's prestige was never more inflated than during the French Revolution, when Rousseau's lofty speculations seemed on the verge of realization. For Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (1748-1836), the leading theorist of the National Assembly, the legislator's function was to "enlighten men about their happiness" and to "correct the evils caused by nature and by men."[10] "The legislator commands the future," proclaimed Saint-Just, that stern advocate of the Reign of Terror. "It is his role to desire good and to perpetuate it; it is his role to make men what he wishes them to be."[11] In the words of "(Ça Ira," the song that filled the air at the great Paris Festival of the Federation, July 14, 1790: "Du législateur tout s'accomplira" (The legislator will accomplish everything).

Such unbounded confidence in the benevolence of the law speaks of the revolutionary legislators' unfamiliarity with their role. To them a constitution was an electrifyingly novel thing. Before the late eighteenth century the French rarely used the word constitution in the modern sense of a body of law instituting and regulating the political order of a society.[12] Most of the deputies to the National

Assembly initially understood their charge to be the restoration of monarchic tradition to the financially and politically bankrupt nation. Thus in anticipation of the salutary effect of their constitution, the participants in the Tennis Court Oath pledged to "maintain the true principles of monarchy."[13] Amid controversy, an audaciously comprehensive notion of the nation's constituent (i.e., constitution-making) power eventually prevailed.[14] Respect for monarchic tradition gave way to a decision to create a new government that would rule and regenerate France.

Leading this radical movement was Deputy Sieyès, who declared in his famous pamphlet Qu'est-ce que le Tiers état? that the will of the nation "is always legal; it is the law itself." Elsewhere he maintained that the nation, in exercising the constituent power ("the greatest, the most important of its powers"), must be unconstrained.[15] In accord with this bold idea of the nation's constituent power, David conceived The Tennis Court Oath as a massive demonstration of coordinated muscular force and included the irreverent detail of lightning striking the royal chapel of Versailles.

Severed from the person of the king, revolutionary law was at once depersonalized and venerated as the expression of the general will. This veneration was expressed in representations of the constitution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen in the roundheaded form traditionally associated with the Ten Commandments.[16] At the same time, the depersonalization of the law can be associated with a taste for certain objects, such as the insignia of the Legislative Assembly (Plate 2).

Having provided France with the means to its regeneration, the Constituent Assembly was succeeded, in 1791, by the Legislative Assembly, mandated to make laws in accordance with the constitution. The Legislative Assembly decreed on July 12, 1792, that its insignia would take the form of tablets of the law inscribed RIGHTS OF MAN and CONSTITUTION , to be worn on a tricolored ribbon, draped across the chest, by deputies engaged in official business.[17] The roundheaded white enamel tablets set in gilded copper demonstrated the Legislative Assembly's pompous taste. "The Triumph of the Law," a song commemorating Jacques-Guillaume Simoneau, the mayor of Etampes killed in a food riot on March 3, 1792, and honored three months later by a Festival of the Law, was in a similar spirit: "Hail . . . to the law! Honor to the citizen who remains loyal to it! Triumph to the magistrate who knows how to die for it! . . . May one cherish it, may one fear it! New French people, march, march under its sign!"[18]

It is tempting to view the tablets worn by the Legislative Assembly as a transposition of the Christian doctrine of grace triumphant over law. For the era of constitutional law had superseded the rule of the monarchy by divine grace. Reference to the tablets of Moses was all the more appropriate in that revolutionary law was intended to share the brevity and immutability of the Ten Commandments. The president of the Conventions Committee of Legislation, Jean-Jacques-Régis Cambacérès, declared regarding his project for a Civil Code (1793) that "few laws suffice for honest men; there are never enough for the wicked." Once these laws were written, "one must dread touching this sacred deposit."[19] As Michelet pointed out, the simple rhyme of the song "Ça Ira" mimicked the simple form in which the Ten Commandments were taught to French children.[20] Behind the lofty rhetoric of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen the constitutional historian Maurice-Charles-Emmanuel Deslandres discerned the self-image of the Constituents as "nouveaux Moïses."[21]

The revolutionaries' veneration of tablets addressed the emotional void opened when the law was dissociated from the person of the monarch and attached to the written text. When Gilbert Romme and his Tennis Court Society celebrated the first anniversary of the Tennis Court Oath, a bronze tablet, inscribed with the oath and borne like a "sacred ark" by four Bastille combatants, was carried onto the holy ground of the Versailles tennis court and affixed to the wall.[22] The patriotic newspaper Révolutions de Paris reported that the procession at the festival held in the spring of 1792 to honor the mutinous Swiss guards of Châteauvieux "opened with the Declaration of the Rights of Man, written on two stone tablets as the Decalogue [i.e., Ten Commandments] of the Hebrews is represented to us, though it is no match for our Declaration." "Four citizens," according to the paper, "proudly carried this venerable burden on their shoulders."[23] On July 14, 1792—two days after the Mosaic insignia was decreed for the Legislative Assembly—a bronze tablet inscribed with the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen was placed in a chest with a copper-bound volume of the constitution and other revolutionary memorabilia and deposited in the foundation of a monument to Liberty being built at the former site of the Bastille.[24]

The sanctity of the law was repeatedly belied by the relentless political instability and violence of the 1790s. The king played an integral role in the governmental mechanism defined by the Constitution of 1791. But that document, unable to survive the increasingly radical course of the Revolution, became obsolete less

than a year after its acceptance. In September 1792 the Legislative Assembly was dissolved, the monarchy abolished, and France declared a republic. The National Convention was assembled to write a new constitution, which, unlike that of 1791, would be submitted to a nationwide vote of confidence. Even the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen was not spared: the new Constitution of Year I (June 24, 1793) was headed by a longer, more truculent version of it than that adopted by the Constituents in 1789. In a print by Louis Laurent after Jean-Jacques-François Lebarbier, the thirty-five articles of the new declaration are inscribed on the familiar roundheaded tablets (Fig. 2).[25]

To lend prestige to the new constitution, the government held the Festival of Unity and Indivisibility on August 10, 1793, the anniversary of the monarchy's collapse. Organized by Jacques-Louis David and conducted by Hérault de Sé-chelles, the president of the National Convention, the festival expressed a bold vision of regenerated France radically different from that which had inspired the Constituent Assembly. The spectacle was at once steeped in a serene primitivist vision of rebirth and aflame with regicidal anger, thus anticipating the coupling of lofty civic zeal with unthinkable crime during the Reign of Terror. Far from unified as it confronted the armed might of the monarchic powers of Europe, France was torn by civil war. But as Mona Ozouf has pointed out, the Festival of Unity and Indivisibility made no reference to the conflicts that imperiled the nation.[26]

The festivities commenced at the former site of the Bastille before a fountain of regeneration, represented by a colossal Egyptoid figure of Nature from whose breasts flowed water. This drink was shared by members of the nation's Primary Assemblies—the regional assemblies that, according to the new constitution, would vote on laws as well as choose the citizens who would elect the national legislature. These delegates carried bouquets of wheat and fruit to symbolize the "sublime alliance . . . between agriculture and legislation" of the ancient republican peoples who had regarded Ceres as "the legislator of societies."[27] They proceeded to the Boulevard Poissonnière, where an arch of triumph had been erected honoring the women who had marched on Versailles demanding bread in October 1789. The crowd assembled at the Place de la Révolution (now the Place de la Concorde) before moving on to the Place des Invalides, where a colossal allegorical sculpture, The French People Crushing the Hydra of Federalism , was displayed.[28]

Fig. 2.

L. Laurent after J.-J.-E Lebarbier, Declaration of the Rights

of Man and Citizen, c. 1793. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Fig. 3.

J.-B.-M. Louvion, The Dagger of Patriots is the

Axe of the Law , c. 1793. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Fig. 4.

L.-J. Allais, print commemorating the Festival of Unity

and Indivisibility, 1793. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

At the site where Louis XVI had been executed, the president of the Convention proclaimed: "Here the axe of the law struck the tyrant."[29] Such a reference to the guillotine expresses the fearsome aspect of the law under the Terror (Fig. 3);[30] here the Enlightenment concept of law as creative and regenerative yields to the Old Regime and biblical notion of law as retributive and lethal. The phrase "axe of the law," moreover, could have been uttered only when the law had been resolutely depersonalized, severed from the person of the king, as it had been, gruesomely, with the decapitation of Louis XVI, January 21, 1793.

The festivities concluded at the Champ-de-Mars where, only three years earlier, the Festival of the Federation had celebrated the fidelity of the king and the nation to the previous constitution. Documentation of France's acceptance of the new constitution was placed on the Altar of the Fatherland and the constitution was enclosed in a cedar ark, as if it bore the very words of Jehovah. The event was commemorated in a print by Louis-Jean Allais that compares the Constitution of 1793 with the tablets Moses received on Mount Sinai (Fig. 4). The caption below

Fig. 5.

P.-M. Alix after Boissier, The Triumph of the Mountain , c. 1794. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

reads: "The republican constitution, like the tablets of Moses, comes from the heart of the mountain in the midst of thunder and lightning."[31]

Such biblical rhetoric struck a common chord with the Constitution of 1793, whose final article states that the text of the constitution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen are "engraved on tablets in the midst of the assembly and in public places." Similarly, the new Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen includes the fearsome commandment, reminiscent of Old Testament prescriptions for summary justice, that "any individual who would usurp sovereignty shall instantly be put to death by free men" (art. 27). And the Mount Sinai allusion flattered the radical section of the Convention popularly known as the Mountain because its members sat on the highest benches of the assembly hall.[32] A color print by Pierre-Michel Alix (Fig. 5) treats the same theme: in it a pair of fiery tablets (not visible in the photograph) send down bolts of lightning against the enemies of the Revolution while a patriotic multitude make merry around a liberty tree.[33] The author of a contemporary broadside entitled The Mountain of Liberty; Mountain of Sinai, Source of French Regeneration, Protected by the Supreme Being professed to "believe in the holy constitution, accepted by the French people August 10, 1793."[34]

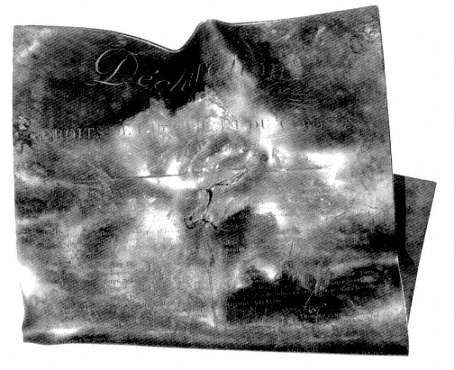

Such was the value the revolutionaries placed on tangible representations of the law that objects bearing the imprint of outdated laws, viewed as abominations, were subject to official vandalism. On April 25, 1793, the Convention ordered the exhumation and mutilation of the tablet with the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen and the volume of the Constitution of 1791 deposited in the foundation of a projected monument on the former site of the Bastille. These objects were now deemed "contrary to the general system of liberty [and] equality of the one and indivisible Republic." On May 3 the decree that this act be performed in two days was presented in the name of the Committee of Public Instruction by Gilbert Romme, whose Tennis Court Society had so passionately honored the authors of these tainted laws. The exhumed objects, Romme specified, "will be broken at the site and the fragments deposited in the national archives as a historical monument."[35] The violated book and broken tablet, now in the National Archives, resonate with morbid pathos (Plate 3 and Fig. 6). Like David's Tennis Court Oath the monument to national unity that could not be completed in the face of political discord—these forlorn objects negate the revolutionary myth of the permanence and sanctity of the law.

Fig. 6.

Bronze tablet inscribed with the 1789 Declaration of the Rights

of Man and Citizen, vandalized in 1793. Archives Nationales, Paris.

The Constitution of 1793 was never put into effect following its poetic consecration at the Festival of Unity and Indivisibility. In the final act of a popular theater spectacle written by two members of the Convention and based on the festival of August 10 a citizen sang: "Oh holy constitution! Your salutary influence will soon dissipate the illusions of the peoples of the earth!"[36] But the perils of war and subversion seemed to necessitate the postponement of this salutary influence. The survival of the Republic of Virtue demanded a stronger executive power than that defined by the new constitution. While France suffered the despotism of the

Fig. 7.

J. Chinard, La République , 1794. Louvre, Paris.

Committee of Public Safety, the Constitution of 1793 was kept in reserve. It remained in the Convention's assembly hall, safely enclosed in its cedar ark.

No hint of this state of affairs is given by Joseph Chinard's austere terra-cotta known as La République (Fig. 7), produced a little more than two months before the execution of Robespierre and the end of the most radical phase of the Revolution. Apparently a model for a monument that, like so many revolutionary projects, was never realized, Chinard's coldly placid figure in a Phrygian cap holds roundheaded tablets, inscribed RIGHTS OF MAN and LAWS, and an oak branch, emblematic of strength.[37]

The dictatorship of the legislature, initiated by the Constituents and brought to a terrible climax during the Terror, ended with the reaction of Thermidor. Robespierre was guillotined, and France was given yet another constitution. The Constitution of Year III (August 22, 1795)—it lasted almost five years, longer than any other revolutionary constitution—opened with a Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man and Citizen, among which was the pronouncement that "no one is a good man if he does not frankly and religiously observe the laws" (art. 5). This homage to the revolutionary cult of law, however, was not backed by confidence in the nation's legislators. A five-member Directory held executive authority, and the legislature was cautiously divided into two separate assemblies. A Council of Five Hundred proposed laws to the 250 members of the Council of Ancients. Identification medals by Nicolas-Marie Gatteaux (1751-1832), distributed to members of the two legislative chambers, display the familiar revolutionary iconography of the law: Mosaic tablets, inscribed with the title of the new constitution, are superimposed on the level of equality and encircled by a serpent biting its tail, emblematic of "the long destinies of the republic and the stability of its legislation" (Fig. 8).[38] This conventional panoply ignored the turmoil of Directory France, beset by financial collapse, brigandage, and rebellion.

Hatred of the legislature had shadowed the development of representative government in France since the days of the Constituent Assembly. But popular French anti-parliamentarianism reached a new intensity during the summer and fall of 1795, when the Convention was purged of its radical element and the directorial Constitution of Year III was instituted.[39] How could there be respect for the law under the Directory when the government relied on measures so exceptional that this phase of the Revolution has been characterized as a permanent coup d'état?[40]

From the outset, the revolutionary legislative record was the subject of a formidable literature of denunciation.[41] It is ironic, in this regard, that detractors of the Constituent Assembly found ammunition in the very passages from The Social Contract that most exalted the legislator. For these critics Rousseau's lofty notion of the lawgiver set into relief the weakness of the Assembly.[42]

The most resounding attack came from across the English Channel. Edmund Burke, in Reflections on the Revolution in France , reprinted eleven times within a year of its appearance in 1790, established a position that became a mainstay of the French Right. Burke denied that a constitution could be "made," insisting

Fig. 8.

N.-M. Gatteaux, membership medal for the Council

of Ancients (obverse), 1797. Musée de la Monnaie, Paris.

that it had to evolve slowly and organically out of social institutions and history, as it had in England, where liberty "has its gallery of portraits, its monumental inscriptions, its records, evidences, and titles." Ignoring this principle, the legislators of France, behaving "like the comedians of a fair before a riotous audience," have given their nation a "monster of a constitution."[43]

Burke's Reflections were applauded by the counter-revolutionary French journal Acts of the Apostles .[44] With an anti-parliamentarian bile that prefigures La Caricature in the 1830s, this satirical royalist paper (November 1789-October 1791) denounced the "debased tigers" of the Constituent Assembly who had forced

Fig. 9.

Opening of the Club of the Revolution , from Acres des apôtres, 1790. Widener Library, Harvard University.

Louis XVI to submit to their "ghastly laws."[45] In Opening of the Club of the Revolution (Fig. 9), published with an explanatory text as the frontispiece to the second volume, the nation's legislators display none of the dignity David would give them in The Tennis Court Oath (see Plate 1). This caricature engages the revolutionaries in a grotesque stage farce, complete with orchestra and fanciful Asiatic scenery. Atop a ladder, Sieyès hands an unwieldy constitution (the inverted pyramid) to Guy-Jean Target, who, because he often served as orator for the Constitution Committee, was malevolently viewed as father to the constitution by the counter-revolutionary press.[46] "Persuaded that a competent juggler could hold it in equilibrium," Sieyès has entrusted the constitution "to the dexterity of the academician Target." Deputy Antoine Barnave is said to be costumed as the Rights of Man: "a shark snout, & decrees in the form of principles in every buttonhole, give him a very expressive air." The bizarre display at the center of the

Fig. 10.

To the Friends of the Constitution , c. 1791. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

proscenium (a balloon filled with flammable air, a lighted lantern, and "the agreeable sound of little bells") symbolizes the "patriotic fire that exalts our divine legislators, the enlightenment and talents that they have shown, and the noise that their eternal operations make in the universe."[47]

Counter-revolutionary caricaturists treated the revolutionary motif of the roundheaded tablets of the law with similar derision. Consider, for example, a curious allegorical tondo dedicated to the radical Jacobin Club, originally called the Society of the Friends of the Constitution (Fig. 10).[48] At the foot of a pyramid

Fig. 11.

Homage to the National Assembly , c. 1791. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

encrusted with portraits—its prototype can be found in a revolutionary print Homage to the National Assembly (Fig. 11)—a chorus of frogs croak in praise of the revolutionary legislators. Its summit obscured by clouds, this monument to folly stands amid an oppressive clutter of emblems. Flames rise from an altar whose serpent of eternity bears a suspiciously goose-like head. The tablets of the Ten Commandments and a bound volume that probably represents the Constitution of 1791 are pressed close to the adoring amphibians.

Fig. 12.

Attributed to M. Webert, The New Calvary ,

1792. Bibliothèque Nationalc, Paris.

Fig. 13.

The French Constitution , 1791.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

A more ominous transformation of the tablets of the law occurs in The New Calvary (Fig. 12), a print sold and perhaps created by Michel Webert (b. 1769), an engraver and dealer in pornographic and royalist prints condemned to the guillotine in 1794.[49] This print contrasts with a revolutionary image of 1791, The French Constitution (Fig. 13). There, a stately personification of the nation uses the scepter of legislative power to engrave a roster of revolutionary reforms on colossal roundheaded tablets of the law suspended from a fasces. The New Calvary transforms these revolutionary emblems into instruments of torture. Flanked by his brothers, the future Louis XVIII and Charles X, Louis XVI is crucified above

Fig. 14.

J. Gillray, The Apotheosis of Hoche , 1798. Yale Center

for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, New Haven, Conn.

roundheaded tablets that bear the names of those banished and anathematized by the Revolution. As the queen pleads for vengeance and the prince of Condé draws his sword, the king is offered a bitter sponge.[50]

The roundheaded tablets of revolutionary law served as a butt for the black humor of the British caricaturist James Gillray (1757-1815) in The Apotheosis of Hoche , an apocalyptic travesty of Hoche's funeral, September 19, 1797 (Fig. 14).[51] The republican anglophobe general, who on July 21, 1795, annihilated a counterrevolutionary assault force that attempted to land at the western coastal town of Quiberon, is cast in the dual role of Orpheus and Antichrist. In a grotesque mimicry of the civilizing legislator-poet Orpheus, Hoche plays a guillotine-lyre above a devastated landscape amid a satanic host of sans-culotte cherubim. Between two apocalyptic beasts are roundheaded tablets inscribed with a satanic inversion of the Ten Commandments.

Burke's attack on the Revolution was seconded in loftier terms by Joseph de Maistre in Considerations sur la France (1796), a book then little known in France but esteemed by the exiled aristocracy.[52] Maistre's fervent devotion to absolute monarchy and revealed religion was informed by a cruel wit worthy of Voltaire. "The more one examines the most apparently active figures of the Revolution," he asserted, "the more one finds in them something passive and mechanical." Maistre viewed the Revolution as a providential purification and punishment that would culminate in the triumph of the French monarchy: "Never has Divinity shown itself more clearly in any human event." And if Providence "employs the most vile instruments, that is because it is punishing in order to regenerate."[53] Such regeneration was hardly of the kind anticipated by those who took the Tennis Court Oath.

Maistre, who later wrote an essay condemning the very idea of written law, had unbounded contempt for revolutionary legislation.[54] The Revolution had created many laws, he argued, because it lacked a legislator. Although he considered Rousseau "perhaps the most mistaken man in the world," Maistre agreed with the author of The Social Contract that durable institutions must have a divine basis.[55] Like other counter-revolutionary polemicists, he invoked the ancienne constitution of France—the unwritten laws and customs by which monarchic France had been ruled for centuries—at the expense of the revolutionary legislators:

France, it is by the noise of infernal songs, the blasphemies of atheism, the cries of death and long groans of innocence with its throat cut, by the light of conflagrations, on the debris of the throne and altars, watered by the blood of the best of kings and an innumerable crowd of other victims . . . that your seducers and your tyrants have founded what they call your liberty .

Against these horrors Maistre held up divine Providence, which would lead France back to its ancienne constitution .[56]

Maistre's caustic brilliance had a ponderous counterpart in the theoretical writing of Viscount Louis-Gabriel-Ambroise de Bonald (1754-1840).[57] In Théorie du pouvoir politique et religieux dans la société civile, demontrée par le raisonnement & par l'histoire (1796), written in exile in Heidelberg, he anathematized the political heresies of modern France. In accord with pre-revolutionary usage, Bonald defined constitution as the traditional, patriarchal, and Catholic order of monarchic society. He regarded the very idea of a man-made constitution as absurd. He presented this position in uncompromising terms at the opening of Théorie du pouvoir :

I believe it possible to demonstrate that man can no more give a constitution to religious or political society than he can give weight to the body or extension to matter and that, far from being able to constitute society, man, by his intervention . . . can only delay the efforts that society makes to arrive at its natural constitution.[58]

Bonald held up Catholicism and monarchy as the foundations of an immutable social order revealed by God ("the supreme Legislator") through the miracle of language. One of the few copies of Théorie du pouvoir to escape confiscation by the Directory fell into the hands of General Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon was supposedly so impressed by the treatise that he wrote to Bonald, offering to have the government pay for a new edition.[59]

Revolutionary law received its ultimate insult on 19 brumaire, Year VIII (November 10, 1799), the day after the abrupt transfer of the two legislative councils from Paris to Saint-Cloud. In response to General Bonaparte's defiance of the Constitution of Year III, a dissident faction among the Five Hundred shouted "Hors la loi!" To be deemed "outside the law" was a crime punishable by immediate execution. Lucien Bonaparte, president of the Council of Five Hundred, saved both the coup d'état and his impetuous brother by having his recalcitrant

Fig. 15.

I.-S. Helman after C. Monnet, Day of Saint-Cloud ,

18 Brumaire, Year VIII, c. 1801. Bibliothéque Nationale, Paris.

colleagues removed from the premises at gunpoint. Madame de Staël received with sorrow the news that "General Bonaparte had triumphed, the soldiers having dispersed the national representation; and I . . . felt in that instant a difficulty in breathing that has since become, I believe, the malady of all those who have lived under the authority of Bonaparte."[60]

The official interpretation of Bonaparte's confrontation with the legislature is represented in a print by Isidore-Stanislas Helman that shows the general beset—like Julius Caesar or the betrayed Christ—by a mob brandishing daggers (Fig. 15).[61] Less respectfully, the last moments of the Constitution of Year III

Fig. 16.

J. Gillray, Exit Libertè a la Francois ! 1799. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

were commemorated by Gillray in a print published November 21, 1799, Exit Libertè a la Francois! or Buonaparte Closing the Farce of Egalitè (Fig. 16).[62] This act of anti-parliamentary violence—whose brutishness Gillray conveys—closed definitively the period of buoyant optimism represented by the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, by David's drawing The Tennis Court Oath , and by the revolutionary festivals.