Colonial Agents and the Constitution of Moro Identity

An inconsistency may be evidenced in American colonial policy toward Philippine Muslims that was at least partly occasioned by the "self-liquidating imperialism" that formed the basis of America's overall Philippine colonial policy. After their brief experiment with indirect rule, American colonial authorities explicitly refused any formal recognition of the aristocracies of the Philippine sultanates or of indigenous legal systems. Muslims were not to be excepted from direct colonial rule; close American supervision was required in order for Philippine Muslims to achieve a level of "civilization" sufficient to allow their integration with their Christian counterparts in an eventual Philippine republic. Despite the official denial of traditional rights of rule, however, American colonial agents came to place great emphasis on the Muslim nobility as implementers of colonial policies intended specifically for Philippine Muslims.

Throughout the course of American rule in the Philippines, a particular set of policies was formulated in reference to a category of colonial subjects denominated as "Moros." Although official American attitudes toward Philippine Muslims lacked the holy war complex that prompted the Spanish use of that designation (and despite the fact that the term was well established as a pejorative among Philippine Christians), American authorities adopted the usage "Moro," with all of its conglomerating and epithetic connotations, as the exclusive term of reference for the entire thirteen Muslim ethnolinguistic groups of the Philippines. It is nearly impossible to find in official documents, even among the writings of the most sensitive American observers, any clear indication of the distinct histories and cultures possessed by the various subject peoples designated as "Moros."[21]

One of the most influential agents in the early American colonial administration of Philippine Muslims was Najeeb Saleeby, a Syrianborn physician who came to the Philippines as a U.S. Army doctor in 1900 (Thomas 1971). Saleeby was assigned to Mindanao and became fascinated with its Muslim inhabitants. He made the acquaintance of numerous prominent Muslims and learned two local languages—Magindanaon and Tausug. He used his knowledge of those languages, and of Arabic, to translate entitling genealogies (tarsila, salsilah ) and law codes (Luwaran) for the main sultanates of the region, including the Magindanaon and Buayan Sultanates. Saleeby was quickly recognized

by colonial authorities as the resident American specialist on Philippine Muslims and in 1903 was appointed Agent for Moro Affairs. In 1905, the same year he published his Studies in Moro History, Law, and Religion (the first scholarly work on Muslim Filipinos published in English), he became the first superintendent of schools of the Moro Province.

Saleeby opposed the move to direct administration of the Muslim regions of the South and, though overruled, he was instrumental in conditioning official attitudes about the governance of Philippine Muslims, and particularly about the utilization of traditional Muslim elites to implement colonial policy. Saleeby's views on the "development" of the Muslims of the Philippines were expressed most cogently in a 1913 essay entitled The Moro Problem .[22] In that work he disputes the popular perception of Moros as savages and religious fanatics. Moros, he observes, "have so little religion at heart that it is impossible for them to get enthusiastic and fanatic on this ground" (1913, 24). Moros do, however, possess relatively sophisticated, if "feudal," political communities ruled by datus. "The datu is God's viceregent on earth. He is of noble birth and the Prophet's blood runs through his veins. The people owe him allegiance and tribute" (1913, 17). He notes further that, for the most part, the datus had not been actively opposed to American aims and that "religion has never been a cause of conflict between Americans and Moros"(1913, 24). Moreover, "the Moros are greatly disunited . . . [E]ach district is inhabited by a different tribe and these tribes have never been united" (1913, 15). It is in the Americans' interest, in fact, to unite the Moros under their traditional leaders in order to initiate a "process of gradual development" (1913, 17). In furtherance of such a goal Saleeby, himself a Christian, declares that "religion" (meaning Islam) "can be encouraged and promoted" for the benefit of both the colonial government and the Moro people (1913, 24). As envisioned by Saleeby, with the reestablishment of "datuships" and "Moro courts," "the individual Moro would find himself well protected and would become more thrifty and intelligent. Moved by a natural tendency to imitate superior civilization, he would unconsciously reform his customs and home life and gradually acquire American ideas and new ambitions. An enlightened Moro community, wisely guided by efficient American officials, would undoubtedly work out its own destiny, and following the natural law of growth and development would gradually rise in wealth and culture to the level of a democratic [meaning Philippine Christian] municipality" (1913, 30).

In these remarkable passages, Saleeby outlines nothing less than the colonial genesis of Morohood. Saleeby was more knowledgeable about the history, culture, and contemporary political culture of the separate Muslim peoples of the Philippines than any other colonial administrator. He knew that the various Muslim ethnolinguistic groups were in no sense united, nor did they possess—jointly or individually—a politically potent oppositional Islamic consciousness. He urges the promotion of Muslim unity, not through the preservation or restoration of individual traditional polities (i.e., by means of straightforward indirect rule), but through the formation of a new transcendent Philippine Muslim identity: through the development of Morohood.

In his essay, Saleeby proposes the creation of Muslim unity for the sole purpose of propelling Philippine Muslims along a path of development parallel to that of Christian Filipinos in order to prepare their eventual integration into an inevitable postcolonial Philippine nation. They should be led on that path by members of their traditional nobility because, regardless of American attitudes toward aristocracies, the Muslim populace affirms their indefeasible right to rule by fact of their hallowed ancestry.[23] Saleeby's account of Muslim political culture accentuates the myth of sanctified inequality and couples it with Morohood. Islam should be encouraged by colonial authorities because it is that which binds the Muslim populace most indelibly to their leaders—leaders who for the most part have been inclined toward cooperation rather than confrontation with the American regime. Moro religion, law, and customs do, of course, require rationalization by imitation of "superior" culture. Through that process of rationalization by imitation, American principles working on this distinct Philippine population—unique primarily because it had not experienced three hundred years of Spanish colonial rule—would achieve an outcome analogous to that devised for Christian Filipinos.

Although Saleeby's specific proposals were never formally incorporated into colonial policy toward Filipino Muslims, many of his recommendations substantially influenced the attitudes and practices of key colonial administrators.[24] Among those was Frank Carpenter, the first governor of the Department of Mindanao and Sulu, who took office in 1914 shortly after the publication of Saleeby's essay. Carpenter expressed his views in a 1919 letter to the colonial secretary of the interior requesting that Princess Tarhata Kiram, the adopted daughter of the Sultan of Sulu, be sent to the United States as a government student. After reporting the "generally accepted" conclusion that it is "practically

futile to attempt the conversion of "a Mohammedan people as such to Christianity," Carpenter restates Saleeby's suggestions about guided development through the agency of Muslim notables.

[It] is essential to the efficiency, commercially as well as politically, of the Filipino people that all elements of population have uniform standards and ideals constituting what may well be termed "civilization"; and as the type of civilization of the Filipino people in greatest part is that characteristic of the Christian nations of the world, the bringing of the Sulu people from their primitive type of civilization to the general Philippine type may be stated as the objective of the undertaking of the Government in its constructive work among them. No more effective and probably successful instrumentality appears for this undertaking than the young woman who is the subject of this communication.

In suggesting particular arrangements for the American education of the princess, Carpenter goes on to list two considerations of "fundamental importance":

That she be not encouraged nor permitted to abandon her at least nominal profession of the Mohammedan religion, as she would become outcast among the Sulu people and consequently her special education purposeless were she to become Christian or otherwise renounce the religious faith of her fathers. . . .

That she be qualified to discuss intelligently and to compel respect from the Mohammedan clergy she should be encouraged to read extensively and thoroughly inform herself, so far as possible from the favorable point of view, not only the Koran itself and other books held to be sacred by Mohammedans, but also the political history of Mohammedanism.[25]

James R. Fugate, the American governor of Sulu from 1928 to 1936, also acted upon Saleeby's suggestions by implementing colonial policies through individual Sulu datus (Thomas 1971, 189). No colonial administrator was more apparently influenced by the views of Saleeby than Edward M. Kuder, who, beginning in 1924, spent seventeen years as superintendent of schools in the three Muslim provinces of Cotabato, Lanao, and Sulu. Like Saleeby, Kuder endeavored to learn local languages and eventually gained proficiency in Magindanaon, Maranao, and Tausug, the languages of the three main Muslim ethnolinguistic groups of the Philippines.

Kuder expressed his views on the education of Philippine Muslims in a 1935 report to the Educational Survey Committee on "the present education of the non-Christian Filipinos," observing that "[t]he chief value . . . of education among the non-Christians has been the

establishment of a linking element among them, very close in thought, feeling and national identity with the country as a whole, while still conscious of the good things in its own cultural background."[26] Writing as the Philippines were about to be granted partial independence (see below) and amid growing Western concerns about Japanese aggression in Asia, Kuder proposes an additional potential political benefit (one not articulated by Saleeby) to be obtained from the education of Muslims. "Through the proper treatment and education" of Philippine Muslims, valuable ties may be established with neighboring Malay nations (all still under Western colonial tutelage), forging a regional compact able to withstand "alien" (i.e., Japanese and Chinese) forces: "And here lies the hope of the Philippines for survival—coalition into eventual Malay solidarity . . . And here lies the value of . . . maintaining . . . by means of education, that linking element of non-Christian Filipinos . . . [F]or this Non-christian Filipino element is largely Mohammedan and the great Malay races . . . are overwhelmingly Mohammedan—not the gloomy and fanatic faith of Arabia, but tempered and moderated by the genial Malay hospitality and courtesy and hence compatible, through a proper and common education, with the Christian Philippine civilization."[27]

Kuder put Saleeby's ideas about datu-led development into practice by undertaking personally the training of a generation of Philippine Muslim leaders. In his travels throughout the Muslim provinces he sought out honors students (all of them boys) from various Muslim groups, most usually the sons of datu families, and fostered them, bringing some of them to live under his roof to be tutored by him. In this manner, Kuder personally educated a considerable number of the second generation of Philippine Muslim leaders of the twentieth century. Datu Adil, who had a distinguished career as an officer in the Philippine Constabulary, was one of Kuder's students. He recalled with fondness his time spent as Kuder's "foster son" fifty years earlier, recollecting that he was "strengthened by Mr. Kuder's discipline." In the course of one of our conversations Datu Adil produced a treasured keepsake, a beautifully bound volume of Burton's translation of The Thousand and One Nights . Mr. Kuder had presented the complete set to him when he left the University of the Philippines, telling him it was important that he appreciate his religion.

In a scholarly paper (entitled The Moros in the Philippines ) published in 1945 on the eve of full formal independence, Kuder looked back on his accomplishments. He observes initially that the term "Moro" is an exotic label affixed by Europeans to Philippine Muslims

in general and one not used among them. He also notes, echoing Saleeby, that more than three centuries of Spanish hostility had failed to bring about an overall alliance among the separate Muslim societies of the Philippines. There follows a revelatory passage: "Within the decade and a half preceding the Japanese invasion of the Philippines increasing numbers of young Moros educated in the public schools and collegiate institutions of the Philippines and employed in the professions and activities of modern democratic culture had taken to referring to themselves as Mohammedan Filipinos" (Kuder 1945, 119). Kuder is here referring indirectly, but with detectable pride, to his protégés, the Muslim students he brought together and personally trained in his seventeen-year career prior to World War II. These young men, he avers, are the very first generation of Muslims in the Philippines to possess a shared and self-conscious ethnoreligious identity that transcends ethnolinguistic and geographical boundaries. Kuder's statement is an oblique assertion that he had accomplished in less than two decades what Spanish aggression was unable to provoke in more than three centuries. He had developed a core group of "Mohammedan" Filipinos. The use of that most emblematic of Orientalist terms suggests that the content of this new shared identity had been at least partly formed by his instruction.

It is apparent that Kuder, following Carpenter's lead, not only educated his students in the arts of "modern democratic culture" but also encouraged them to approach Islam (in Carpenter's words) "from the favorable point of view"—that is to say, through the eyes of Western arts and sciences. That at least some of Kuder's students referred to themselves as Mohammedans is attested to by the formation in 1932 of the "Mindanao and Sulu Mohammedan Students' Association," a small organization composed of Philippine Muslim students at the University of the Philippines in Manila, many of them former students of Edward Kuder. In a 1835 letter to Joseph Ralston Hayden, the then vice-governor general of the Philippines, Salipada Pendatun, Kuder's star pupil (see below) and a principal organizer of the association, described its aims: "Our primary purpose in view is to act as the unofficial representative of our people at home; in order to protect their rights and interests, to help them realize the value of education; to inculcate in them the value of cooperating with the leaders of Christian Filipinos in working for the common welfare of the country."[28]

Kuder's aim was to create an educated Muslim elite trained in Western law and government and able to represent their people in a single Philippine state—a cohort ready to direct Muslim affairs through

enlightened forms of traditional rule. That goal was realized in great measure in the careers of Kuder's students. Most became lawyers, civil servants, and politicians; married Christians; and remained formally monogamous. At the same time, they conserved their traditional roles as Islamic adjudicators in what were now nongovernmental tribunals and as sources of moral authority.

Datu Salipada K. Pendatun

The most prominent of Kuder's former students in Cotabato, and one of the most successful of any of his "foster sons," was Salipada K. Pendatun.[29] Datu Pendatun (more commonly known as Congressman Pendatun) became one of the most nationally prominent and influential of the postcolonial datus of Cotabato. Pendatun was born in 1912 at Pikit, Cotabato, of noble parentage. His father, the Sultan of Barongis, a small upriver sultanate, died when he was still a boy and Pendatun was brought to live with Edward Kuder, becoming one of his first students. Pendatun retained a close relationship with his former teacher until Kuder's death in the early 1970s.

After leaving Kuder's tutelage, Pendatun studied law at the University of the Philippines in Manila. In 1935, the Philippine Islands were granted partial independence under Commonwealth status by the United States, with the promise of independence in ten years' time. In that year, Pendatun, still a law student, wrote another letter to Vice-Governor General Hayden noting the rush of immigrants to Cotabato induced by the Commonwealth's new road-building policy and the increasingly disadvantaged position of Muslims vis-à-vis Christian settlers in attempting to acquire public lands. He urged (unsuccessfully) that a special agent be appointed to help Muslims with the registration process (Thomas 1971). Datu Pendatun graduated from the University of the Philippines in 1938 (the first Magindanaon to do so) and was appointed by Philippines President Quezon to the Cotabato Provincial Board to replace Datu Sinsuat, recently elected to the National Assembly. Pendatun was elected to the same post in 1940 (Glang 1969).

The transitional Commonwealth period of American sovereignty in the Philippines was profoundly disrupted in 1941 by the Japanese invasion and occupation. During the war against the Japanese, Pendatun led one of the most active guerrilla units in Mindanao, a group that included Americans and Christian Filipinos as well as Magindanaons. In 1942, his fellow guerrilla leaders selected him as their "General"

5.

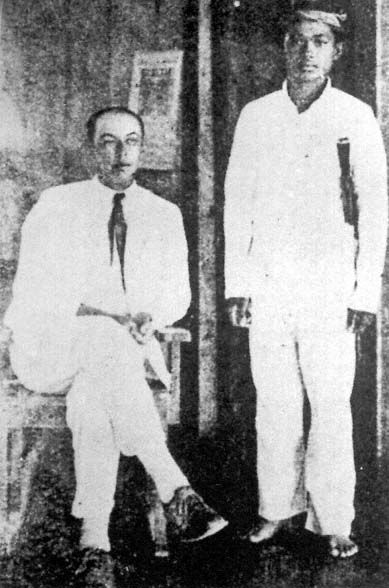

Edward Kuder (seated) with the young Salipada Pendatun, 1927. Pendatun,

shown here in the simple garb of a Muslim schoolboy, was the son of the Sultan

of Barongis, as well as Kuder's foster son and star pupil. He went on to become

the most prominent and influential Philippine Muslim politician in the post-

independence period. Courtesy of Phillipines Free Press .

(Thomas 1971, 301). In recognition for his war efforts, Pendatun was appointed governor of Cotabato in 1945 by President Sergio Osmena.

Datu Pendatun's early career was one of the most successful of any of the second-generation colonial datus. He is representative, however, of a number of other Philippine Muslim political figures of his generation (some of them also former students of Edward Kuder). By the founding of the Philippine republic in 1946 they were politically well established with ties to the apparatus of national rule in Manila and able to command local allegiance on the basis of traditional social relations. This new Western-educated Muslim elite had also begun to develop a self-conscious transcendent identity as Philippine Muslims. That consciousness derived not from opposition to American rule but rather from studied adherence to its objectives.

The peculiar form of direct colonial rule established by the Americans for Philippine Muslims—combining official repudiation of the authority of traditional rulers with a wardship system for certain Muslim elites specifically designed to enhance their abilities as "Mohammedan" leaders—produced effects inverse to those found in another Southeast Asian colonial system attempting to rule Muslims. The Dutch development of adatrecht for colonial Indonesia was intended to de-emphasize Islam by "constituting local particularisms in customary law [and] favoring the traditional authority structures linked to them."(Roff 1985, 14). While Dutch policies fostered (indeed created) ethnic divisions among Indonesian Muslims, the attempts by various American colonial agents to rationalize and objectify the Islamic identities of a generation of Muslim leaders provided the basis for ethnicizing Islam in the Muslim Philippines. As we shall see, that newly cultivated Muslim ethnic identity acquired particular saliency when Muslim political leaders found themselves representing a small and suspect religious minority in an independent nation dominated by Christian Filipinos.