Chapter Three—

Father Knows Best about the Woman Question:

Familial Harmony and Feminine Containment

Lora: " . . . Yes I'm ambitious, perhaps too ambitious, but it's been for your sake as well as mine. Isn't this house just a little bit nicer than a cold-water flat? And your new horse, aren't you just crazy about it?—"

Susie: "Yes, but—"

Lora: "And that closet of yours—"

Susie: "Has all the dresses fit for the daughter of a famous star."

Lora: "Now just a moment young lady. It's only because of my ambition that you've had the best of everything. And that's a solid achievement that any mother can be proud of."

Susie: "And how about a mother's love?"

Lora: "Love! But you've always had that!"

Susie: "Yes, by telephone, by postcard, by magazine interviews, you've given me everything . . . but yourself."

—Imitation of Life, 1959

As we've moved from the thirties through the wartime years, we have seen that the representations of mothers and daughters underwent profound shifts. Fundamentally, the move was from an idealized dream of the mother as sacrificial lamb to her daughter's social ascendancy to a much harsher nightmare of the mother as malevolent force on her daughter's struggling psyche, particularly as the war came to a close, and the specter of a more permanent working mother provoked anxiety. Moving now to the years after the war, to the late forties and fifties, we face the question of how the culture industry "handled" the personal and social turmoil that now characterized almost any discussion containing the terms "woman" or "mother."

The years after World War II are crucial to any examination of

the mother/daughter relationship, for it is roughly between 1945 and the early 1960s that we witness the hardening and solidifying of what Betty Friedan was to call "the problem that has no name." Indeed, Friedan's ground-breaking book, The Feminine Mystique , detailed for the first time the tremendous backlash experienced by women during the postwar years. Her chronicle of middle-class, white women gone slightly mad under the pressures of suburban isolation and severely circumscribed lives opened the door for both a resurgence of women's activism in the seventies and a reexamination of what was hidden under the pleasant facade of fifties consensus.

It is a particularly important period for the history of women generally, as many feminist historians have documented. If the war brought women into the work force and into public life with a vengeance, then the postwar period (really beginning midwar) attempted to shunt them back off into the domestic, familial world from which they had been recently liberated. As Mary Ann Doane argues: "'Rosie the Riveter'" was conceived from the beginning as a temporary phenomenon, active only for the duration, and throughout the war years the female spectator-consumer was sold a certain image of femininity which functioned to sustain the belief that women and work outside the home were basically incompatible."[1]

Women entered the labor force in unprecedented numbers during the war, often at the urging of an enormous government campaign that exhorted women to give their all for the war effort. But as the men began to return home from Europe and the Pacific, many women were also forced to return "home," literally: by 1946, four million fewer women were working than had been at the peak of the war.[2] In fact, the retrenchment started midwar: "Government propaganda, midwar, did an about-face. Because the original exhortations to women to do war work had never challenged the core of ideas about femininity, because no one had suggested that work was more than a sacrifice women had willingly made for the most motherly of reasons, the shift was an easy one. The message was clear: although women could do anything, authentic women would choose to be at home with their families."[3] Yet government officials and labor leaders alike began to realize that many women would not simply step down from their jobs and offer them up to

the returning GIs. A 1944 Department of Labor survey showed that 80 percent of former working women, 75 percent of former students, and 50 percent of former homemakers hoped to continue working.[4] Clearly, the work of ousting women from the public sphere was going to be work indeed.

Numerous feminist historians have pointed out how the late 1940s and most especially the 1950s represented a period of regression for women when many of the gains and freedoms experienced during the war years were lost or, more accurately, wrenched from women in the name of a newly constructed familialism. As many historians have demonstrated, the familialism of the postwar years was not a "return" to a more "traditional" ethos but was instead a fundamentally new phenomenon: "The legendary family of the 1950s . . . represented something new. It was not, as common wisdom tells us, the last gasp of 'traditional' family life with roots deep in the past. Rather, it was the first wholehearted effort to create a home that would fulfill virtually all its members' personal needs through an energized and expressive personal life."[5]

It need not have turned out the way it did. Traditional gender roles had been challenged both by the depression and, much more extensively, by the experience of the war and women's work during those years. In addition, growing access to birth control and higher education could have encouraged a more progressive attitude toward the position of women in American society. The domestic containment of the postwar years was thus not a simple continuation, or even a resurgence, of an already existing ethos. It was a backlash of significant proportions related not only to establishing the nuclear home as the paradigmatic social/personal site, but also to establishing an ethic of consumerism as a vast bulwark against the threat of communism abroad and the internal "other" within. As Elaine Tyler May reveals, the famous 1959 Nixon-Khrushchev "kitchen debates" used women as central elements in their respective visions of the "good life." Anti-Communist writers in the United States ridiculed the "unfeminine" (working) Soviet women, implying "that self-supporting women were in some way un-American. Accordingly, anticommunist crusaders viewed women who did not conform to the domestic ideal with suspicion." The policy of containment was thus always something more than externally motivated. "In Nixon's vision, the suburban ideal of home

ownership would diffuse two potentially disruptive forces: women and workers."[6]

The growth of the suburbs in the postwar expansion played no small part in this backlash, as women were ousted from their public, work environment and relocated in the relative isolation of the new suburban tract home, now itself symbolizing the changed ideal of the American Dream. As Cowan points out in her work on household technology, the relationship between the new home products, the suburbs, and the nuclear family ideal was close indeed: "The move to the suburbs carried with it the assumption that someone (surely mother) would be at home to do the requisite work that made it possible for someone else (surely father) to leave early in the morning and return late at night, without worrying either about the welfare of his family or the maintenance of his domicile."[7]

Warren Susman observes that the term "family" itself came to define not only a new media emphasis (the domestic sitcom) but a whole range of commodities and modes of existence: "The new medium of television found its function in domestic-centered television shows, from 'I Love Lucy' to 'I Remember Mama,' all seen in the 'family room.' (Indeed, think of all the family words enveloping the new suburban lifestyle: family-size carton, family room, family car, family film, family restaurant, family vacation.) In essence, one can represent the new affluent society collectively in the image of the happy suburban home."[8]

Certainly, the fifties are most often remembered as the period in which the ideal of the traditional nuclear family with 2.4 kids, a suburban tract home, station wagon, and assorted barbecue grills, pets, and home appliances restructured the social and cultural terrain. The mass media played a central role in this restructuring, for not only was the new medium of television filling up the "family room" and occupying a larger and larger space in the social body, but the images themselves were crucial to orienting both women and men to the new social and sexual order, which was organized to a great extent around the new consumerism born of the postwar economic boom.[9] As Lipsitz points out, early television production was an influential addition to the more "official" discourses of domesticity and consumerism: "Commercial network television emerged as the primary discursive medium in American society at the precise historical moment that the isolated nuclear family and

its concerns eclipsed previous ethnic, class, and political forces as the crucible of personal identity. Television programs both reflected and shaped that translation, defining the good life in familycentric, asocial, and commodity-oriented ways."[10]

If women had previously been targeted by the mass media as potential workers, "Rosie the Riveters" hammering away at the hulls of fighter planes while their noble menfolk were off fighting fascism, they now were targeted as "happy homemakers," suburban wives and mothers keenly attuned to the newest home products, eagerly reading their Dr. Spock, and supporting their husbands' climb up the company ladder.

A sample from an episode of the classic fifties sitcom, "Father Knows Best," typifies the explicit ideological work of popular culture in orienting men and women toward traditional sex roles. In this episode, teenage daughter Betty hears a lecture from a vocational counselor in her high school and decides she wants to be an engineer. When she gets a summer job working on a highway surveying team, her family is appalled at the idea of a girl doing that sort of work. Betty goes ahead, citing a "changing world," and meets up with a sexist (but handsome) foreman on her first day. He constantly berates her ("Why are you doing this?" "What are you running away from?"), and Betty runs home in frustration. The young man comes to the house that evening, gives a passionate speech about the need for women to be in the home, and wins over the chastened and enamored Betty.

The ideological impetus of this episode is forthright and explicit. Betty's mother plays the part of a rather passive sex-role socializer while her father plays the central role of arbiter of values and morality. The running joke throughout the episode centers around Betty's refusal to be interested in the new dress her mother has purchased for her now that she is concerned with her career. The mother continually tries to entice her with the dress, to lure Betty away from her egalitarian fantasies and toward the replication of her mother's life. The episode ends with a newly coquettish Betty running upstairs and slipping on the new dress to entice the young male engineer who has come to woo her away from work and toward romantic love and domesticity.

The engineer's speech is filled with references to the new expanding world of the fifties (the new highway system, the housing

boom) and the desire to have a lovely "sweet girl" to come home to. The sainted image of the wife and mother is here clearly depicted as the legitimation of postwar growth ("We do it all for her"). Betty, overhearing the speech (made to the father, of course), runs upstairs to transform herself from strident girl-engineer in jeans and boots to beguiling teen angel in dress and bows. Father looks on happily. By the show's end, the realities of a "changing world" are safely contained within the rhetoric of both essential differences and romantic love. The idea of the working woman is put down firmly and vigorously.

During this period, social messages became vehement in opposition to the enhancement and development of work opportunities for women, pervading all areas of popular culture: "A survey of women's roles as portrayed in magazine fiction in 1945 showed careers for women depicted more unsympathetically than since the turn of the century."[11] Yet the contradictions of this period are legion. The recuperation of women as primarily domestic was facilitated by playing up the images of "hearth and home" and celebrating the virtues of motherhood and family, particularly as the decade came to a close and the domestic ideologies of the fifties began in earnest. The old language of biology as destiny often merged with the new language of functionalist social science to provide ample evidence for the ineluctability of rigid gender positionings. In a 1956 article in Parents' Magazine , the well-known psychiatrist Bruno Bettelheim echoes his Parsonian colleagues in arguing for a "thinking based on . . . inherent function" in which "the completion of womanhood is largely through motherhood, but fulfillment of manhood is not achieved largely through fatherhood."[12]

This image of the fifties, as a period of happy and fulfilled homemakers waxing freshly washed floors and beaming brightly at their brood through their suburban picture windows, is one we strongly identify with the TV sitcoms of that period, particularly such shows as the hugely popular "Father Knows Best" and "Leave It to Beaver." If any one TV image says fifties, it is that of June Cleaver, ever patient mother, loving wife, and cheerful consumer, dispensing love and cookies to husband and madcap sons alike.

This concerted effort to regain a sense of stability about women and their place was clearly motivated by a felt concern over the realities of change, struggle, and confusion:

Despite its adoption of historical conditions from the 1950s, the suburban family sitcom did not greatly proliferate until the late 1950s and early 1960s . . . while the women's movement was seeking to release homemakers from this social and economic gender definition. This "nostalgic" lag between the historical specificity of the social formation and the popularity of the suburban family sitcom on the prime-time schedule underscores its ability to mask social contradictions and to naturalize woman's place in the home.[13]

In many senses, the postwar years were marked first and foremost by the reorganization and restructuring of sexual roles and ideologies. The anger and moralism of popular antiwoman texts such as Lundberg and Farnham's Modern Woman: The Lost Sex only attest to the extreme unease of these years, the sense that something had begun that could not wholly be kept under wraps, not entirely contained under the happy mask of hearth and home.

At the same time these ideologies of maternal beneficence were blossoming, the specter of Philip Wylie's malevolent mom reared her ugly head. Wylie's description of a society gone soft, ruined and shriveled by hordes of devouring, emasculating moms, is as much a part of the familial discourse of the forties and fifties as are the happy homemakers and cake-baking mothers.

These two aspects of postwar ideology — the glorification of motherhood and its simultaneous denigration by the exponents of "momism" — may seem to be in contradiction. But this double message, this insoluble paradox, is itself the defining discourse of mothering in the fifties, most especially of mothering daughters. The images of the devouring mother and the virtuous mother are part of the same double bind. Both are mystifications, both the haloed idealization and the vicious demonization, that further distance mothers and daughters from their own complex, lived reality. The fear, anger, and misogyny found in popular texts such as Wylie's Generation of Vipers and in many of the melodramas of the period are not an aberration, minor, or inconsequential. Rather, the attempt to erase mom, to find her guilty and responsible not only for her children's miserable failures, but for the failures of society as well, is part of the same ideological moment that locates June Cleaver and Mrs. Anderson as the ultimate examples of virtuous motherhood. As Ann Kaplan notes, this pattern was already beginning by the thirties:

But 30s filmic narratives already show increased attention to the Mother's responsibility for the child's psychic, as against social, health. The emphasis shifts in an interesting way from the 20s focus . . . on the mother as moral (Christian) teacher, to the greater burden of creating happy, well-adjusted and fulfilled human beings. Instead of being the agent for shaping the public, external figure (the man/citizen) the Mother is now to shape the internal, psychic self. By the 40s, aberrations in the grown-up child are her fault.[14]

This theory cannot simply be reduced to "two sides of the same coin." Rather, the more appropriate metaphor might be a mirror: but this time not Lacan's mirror, into which the male child gazes, signifying his own reality and his own otherness, but the funhouse mirror into which the anxious mother stares. This mirror splits and fractures her image, distorts it, bends it. There is no single image, no reflection of the self she believes herself to be. All images are freakish, all contorted, yet unified by their shared abstraction, joined by their fictiveness.

Many of the critiques of motherhood that emerged during the 1940s and 1950s (and reemerged with the new right/moral majority of the 1980s) draw a very firm connection between the evils of mothers and the evils of the developing mass society. Mass culture (and most writers include in this concept the new home technologies) is here seen as replacing the intimate familial environment in which a mother's love and nurture provided the sustenance and growth for the entire community. Women have lost their place in the world and now, having been made redundant by the new technologies, are looking for gratification in all the wrong places: "With the coming of an industrial civilization, woman lost her sphere of creative nurture and either was catapulted out into the world to seek for achievement in the masculine sphere of exploit or was driven in upon herself as a lesser being. In either case she suffered psychologically."[15]

This almost preindustrial yearning for a return to a time when men were men and women were mothers manifests itself in the attacks on working women made in films like Mildred Pierce . Mildred has tried to be "both a mother and a father" (a line echoed later by Faye Dunaway in her portrayal of Joan Crawford in Mommie Dearest ) and, in so doing, has created a monster child.

As we move into the 1950s and firmly into a postwar world, many

themes from the malevolent mother era of the 1940s remain the same, but the specific depiction and narrative resolution change significantly. There were two primary and simultaneous responses to the changing roles of women. The first can be seen in such films as I Remember Mama and Little Women and such TV shows as "Father Knows Best," "Mama," and "The Donna Reed Show." These images yearned for the (always fictional) good old days when mothers were all-tolerant and all-sacrificing. In many ways, these nostalgic images of traditional family life refer back to depression era films such as Stella Dallas in that they posit a benign and loving mother who is unproblematically governed by a maternal instinct of sacrifice and familial devotion. These images were often set in either a pseudo-Victorian past or a new suburban idyll, thus alluding not only to the benign vision of maternal sacrifice, but also to nineteenth-century ideals of true womanhood: "With their stress on manipulative femininity and the importance of purchasing marital harmony at the cost of a woman's individuality, the postwar themes closely resembled those of the nineteenth-century cult of domesticity."[16] Women's magazines consistently advocated not only the psychological dictum of maternal responsibility for the growth and development of husband and children, but the social doctrine of maternal responsibility for the growth and development of Western civilization:

They hold human happiness in their hands. Theirs is the power to make or mar human personalities, to supply a core of warmth and security for husband and children, or to withhold this. Theirs is the responsibility, as homemakers, to see that the same values are found throughout the community . . . a mother's responsibility for human living does not end with her home. Her home is not a desert island. It is part of a larger community, responsible for it and dependent on it. As members of this larger group, mothers must see to it that all the children of the community have good schools, good recreation, good training in democratic living.[17]

In these nostalgic representations, mothers and daughters are seen as united in their domestic orientation as well as in their position within the family. In both "Father Knows Best" and "The Donna Reed Show," the teenage daughters are seen as extensions of the mother—they help out in the kitchen, participate in mother's household chores, and laugh knowingly along with mother when dad and the boys act up.

The second response was far more interesting in that it obliquely acknowledged that women were not solely domestic and set out to explore the issues that arose from this "new paradigm" of work and family for women. This would include such films as Imitation of Life and Peyton Place and, surprisingly, many articles in women's magazines that began to discuss the new working mother and often (tentatively) supported women in their desire to remain in the labor force after the war had ended. More significantly, this second line of response continued the often vitriolic attacks against working mothers found in such 1940s films as Mildred Pierce , referring back to these complex wartime representations. Popular texts helped exacerbate this distress over the working woman.

This tension between the nostalgic image of the domestic mother and daughter and the tormented image of the working mother and neglected daughter characterizes this period. Yet these seemingly disparate representations are united not only by their shared hyperbole but also by their insistent emphasis on domesticity as the happiest possible route for women. Both sets of representations convey the feeling of a familial world in crisis. Both the nostalgic response and the angry response are so widely drawn, almost comical in their outlandishness, that the answers they propose are almost always fractured, unsteady, and not quite believable.

I Remember Who? Nostalgic Domesticity

Two films of the early fifties explicitly harken back to an earlier era when ideologies of the companionate marriage and scientific management merged in the public consciousness. Both Cheaper by the Dozen and Belles on Their Toes tell the story (based on fact) of the rather large Gilbreth family, ruled with engineering efficiency by the pioneer of industrial management, Frank Gilbreth, who dies suddenly toward the end of Cheaper by the Dozen . The mother, a "lady engineer" herself, vows to carry on Frank's pioneering work; thus there is a 1952 sequel, Belles on Their Toes .

Opening with a grayed mother attending her last child's college graduation, Belles on Their Toes then goes entirely into flashback, beginning where the first film left off, with mother trying to keep the family together despite financial woes and the sexism of potential employers. In a portrait typical of the romanticized fifties im-

ages (even those set in an earlier period, as is this film), young adult daughter is depicted as her mother's confidante, a "little mother" to her younger siblings. But for all the lightness and cheery aspect of this breezy comedy, the underlying fear of daughter's "spinsterhood" and the desire to reconcile her to her femininity cannot be completely evaded. Eldest daughter Ann (Jeanne Crain) finally meets the man of her dreams, the brash young doctor, Bob. Bob, in true fifties fashion, wants them to get married right away. Ann at first agrees, but then she puts Bob off to allow her mother to take a teaching position at Purdue, vowing she'll care for the younger children. But mother will have none of this sacrificial nonsense. Upon discovering the source of discontent between Ann and Bob, she sets out to confront Ann:

Mother: "Why do you have to wait?"

Ann: "Oh mother, it's just that you have this wonderful opportunity to go to Purdue and I ought to stay home so the others can have the chance I've had."

Mother: "And how long did you figure that would take?"

Ann: "I don't know. A year, two."

Mother: "Why not 15 or even 20? By that time we may have Jane married off. Or maybe she'll decide never to get married. And you'll both be old maids and live with me forever. Is that why I've kept this family together? So I can have spinster daughters around the house? Is that why?"

Thus the intersection of this problematic double bind for mothers of daughters is how to empower them to think that life is not only wife and motherhood, yet make them fully understand that they will be somehow freakish or pitiful if they do not become wives and mothers.

Nostalgic representations of mothers and daughters continued in a variety of media throughout the decade. An interesting case is that of I Remember Mama, noted for both its warm invocation of "old-time" family values and its negotiation of ethnicity in an age of consumerism. As Serafina Bathrick notes, I Remember Mama has a long and unusual media history: "I Remember Mama was originally written as a novel. It was serialized in a popular magazine, and was soon adapted for Broadway. It played a long and successful run during the late war years, and was finally bought for the screen rights

to a high-budget movie released in 1948. The RKO film was not the end, for "I Remember Mama" was among the most successful early TV series, and was again revived on Broadway in 1979 as a musical."[18] Told from the point of view of Katrin Hansen, the young writer who lovingly details the trials and tribulations of an immigrant family in the city, I Remember Mama proposes the sturdy and no-nonsense Old World mother as muse to the developing daughter of modernity. Mama Hansen is here the mediator between the Old World and the New World, reconciling emerging adult daughter Katrin to the ways of the new mass society without propelling her into a world wholly nondomestic:

Within the discourse of the day, I Remember Mama steered a middle way between hysterical anti-feminist tirades (like Philip Wylie's Generation of Vipers ) that charged domineering mothers with destroying the independence of American children, and the emerging war and postwar feminist consciousness stimulated by women's success in securing and maintaining war production jobs. The film featured Mama as a source for reconciliation, as a means of proving that threatening changes could be resisted while one accommodated to progress.[19]

The TV series, "Mama," which ran from 1949 to 1956 on CBS, replicated the essentially nonconfrontational relationship between mother and daughter, albeit with a greater focus on consumerism and the nuclear ideal. As Lipsitz notes: "Over two decades and five forms of media, the Hansens changed from an ethnic, working-class family deeply enmeshed in family, class, and ethnic associations, to a modern nuclear family confronting consumption decisions as the key to group and individual identity."[20] What is stressed in representations like these is the essential continuity of mother and daughter, not far from the continuity assumed in nineteenth-century representations and writings. Although daughter might move out of the maternal orbit by choosing different work, her way there is paved by her mother's skills and the preeminent values of home and family: "Mama's old-fashioned female identity provides the key breakthrough for Katrin's aspirations to become a professional writer. When Katrin despairs because her stories have been rejected and complains that she needs the critiques of an expert, Mama uses her traditional skills to launch her daughter's career."[21] Here, as in the film Little Women and the TV series "The Donna

Reed Show," is a world unlike that of the tortured melodramas of the 1940s, one in which mothers and daughters seemingly exist in carefree harmony, disrupted only occasionally by the angst of adolescence. But this nostalgic move was itself contradictory, for even classic fifties happy-family sitcoms such as "Father Knows Best," while ostensibly benign in their depiction of the mother/daughter relationship, created in no uncertain terms an ideological context in which the attempts of either mother or daughter to escape the confines of suburban domesticity were soundly put down. The tendency toward a more refined and glitzy version of "momism" was stronger than its nostalgic counterpart.

Momism Revisited: "Be a Real Woman and Like It"

The publication in 1942 (before America had entered the war and thus before large numbers of women had entered the wartime work force) of Philip Wylie's classic attack on American women, Generation of Vipers , signaled the beginning of one of the darkest periods in the history of ideologies of motherhood. Wylie's thesis, that American women had become omnipotent "moms" damaging the psyches of their offspring, the masculinity of their mates, and the vitality of their country, was the initial salvo in a barrage of mom bashing that took hold of the popular imagination, soon followed by the publication in 1943 of David Levy's Maternal Overprotection and in 1947 of Ferdinand Lundberg and Marynia Farnham's popular and vicious Modern Woman: The Lost Sex . Although written in the forties, these texts provided the backdrop to the continued psychologization of the mother/daughter relationship. The language of both overprotection (Levy) and neglect and malevolence (Wylie and Lundberg and Farnham) continued into the fifties, albeit with less rancor and vehemence.

Nina Leibman has argued that fifties films continued the evil mother motif from the forties, presenting a very different version of motherhood than is typically associated with the period. She sees a much less rosy discourse, one, in fact, in which mothers represented a quite malevolent force in their children's lives: "The cinematic family melodramas of the 1950s, then, seem to exhibit an attachment to Wylie's Momism. Mothers are accused of being too

smothering and are then relegated to a marginalized existence within the narrative, where they can witness (with admiration) the blossoming of the crucial familial bond, that between father and son." Leibman argues that this erasure, this marginalization, links fifties television to its filmic counterpart: "Both media depend on a systematic erasure of the mother in order to ensure an emphasis on the father's role in raising his children."[22]

This erasure is certainly apparent in the television sitcoms of the period, as "Father Knows Best" amply illustrates. Sitcom mothers seem absent, anonymous, or inconsequential: "It is possible to discern in domestic comedy programming of the period a concerted effort to deemphasize the mother's importance in the lives of her children; indeed, she is presented primarily as a domestic servant."[23] Interestingly, in an era that both celebrated and derided the mother, it was the father (or often the symbolic father figure in film melodramas such as 1959's Imitation of Life ) who reigned as head of household and pivotal figure in his children's lives. The father/child interaction also proved the most substantive, in terms of both narrative structure and ideological weight.

Fathers seem to have been brought back into the picture as a result of the "realization" (promoted by Wylie, et al.) that mothers were ruining their children. If maternal instinct was now aggressive and predatory, if moms ruled the earth and made their children rue the day, then fathers needed to reenter the family fray and set things straight. "Father Knows Best," for all its innocuousness, implied in its very title that Moms may be cute and addle-brained (or mean and malevolent), but when it really comes down to the important issues of child rearing and family life, father really does know best. As many critics have noted, the father-centered family sitcoms of the late 1950s and early 1960s were perhaps a concerted response to what was seen to be a surfeit of "bumbling dads" in the media:

"Father Knows Best" and "Leave it to Beaver" . . . shifted the source of comedy to the ensemble of the nuclear family as it realigned the roles within the family. "Father Knows Best" was praised by the Saturday Evening Post for its "outright defiance" of "one of the more persistent cliches of television and scriptwriting about the typical American family . . . the mother as the iron-fisted ruler of the nest, the father as a blustering chowderhead and the children as being one crack removed from juvenile delin-

quency." Similarly, Cosmopolitan cited the program for overturning television programming's "message . . . that the American father is a weak-willed, predicament-inclined clown [who is] saved from his doltishness by a beautiful and intelligent wife and his beautiful and intelligent children."[24]

The title of the popular 1950s melodrama, Imitation of Life , implies that the life of a career woman (Lana Turner's character, in this case) is only an "imitation" of the real thing, presumably Mrs. Anderson's life. Directed by Douglas Sirk, one of the great melodrama auteurs , the film exemplifies the double bind mothers in the fifties faced in both the narratives of popular culture and, I would venture, the experience of their everyday lives. Imitation of Life was a 1959 remake of a popular Fannie Hurst novel originally produced in 1934, starring Claudette Colbert. It is the story of two mother/daughter couples: one black and one white. This racial theme is vitally important here, not only for what it reveals about the racial dynamics of American society in the 1950s but for the part it plays in this specific narrative and in the melodrama genre in general. If in the 1930s films such as Stella Dallas played out class conflict through the mother/daughter relationship as metaphor, then in the 1950s, in a film like Imitation of Life , the racial "issue" was refracted through familial interactions. Under the booming, "happy days" exterior of 1950s life, beneath the contemporary surge of rose-colored nostalgia, life was much more fraught, much more complex and disturbing, than popular memory would have it constructed.

The impact of McCarthyism on all areas of popular culture has been well documented.[25] Not only were producers, screenwriters, actors, and directors blacklisted, but the culture industry itself initiated anti-Communist imagery and narratives. These films and TV shows were often overtly anti-Communist, portraying an FBI agent or U.S. spy engaged in a holy war against the Eastern European infidels or a brave scientist battling invaders from another planet. But more often than not the ideology of anticommunism manifested itself in more subtle and oblique ways and was implicitly connected to other ideological agendas, particularly ones concerning the family, with which the red scare found common ground. As Elaine Tyler May notes, the relationship between the cold war and domesticity was close indeed: "With security as the common thread, the cold

war ideology and the domestic revival reinforced each other. The powerful political consensus that supported cold war policies abroad and anticommunism at home fueled conformity to the suburban family ideal. In turn, the domestic ideology encouraged private solutions to social problems and further weakened the potential for challenge to the cold war consensus."[26]

As usual, the melodrama was a central site for the production of domestic ideologies. Imitation of Life is an exceedingly complex and contradictory melodrama, its overpowering, glitzy style often drowning out the more explicit ideological implications. Although the role of Lora Meredith is certainly similar in many ways to the career woman equals maternal deprivation theme of earlier films like Mildred Pierce , the presence of another mother/daughter couplet and the racial theme complicates this otherwise routine story of a mother's climb up the ladder of success and the havoc it wreaks on her home life. Fundamentally, this is another film highly critical of career women, particularly as seen in the context of them as parents. The very title and theme song, Imitation of Life , attest to the "falseness" of a working woman's life ("What is love without the giving? Without love, you're only living . . . an imitation, an imitation of life").[27]

There are two central narrative strands—two parallel stories—in this film that unify around the core issue of "mothering." Lana Turner plays Lora Meredith, a widow recently moved to New York who is trying to make it in the theater and raise her daughter, Susie. The story of Lora's rise is joined early on with that of another mother and daughter, Annie and Sara Jane Johnson (played by Juanita Moore and Susan Kohner), who come to live with/work for "Miss Lora" before she has made it and stay on with her through her success.

Certainly, this success and its repercussions construct a central ideological moment of the film. Lora, like Mildred, wants to give her daughter everything; and it backfires, as Annie lets Lora know after they've moved into a glamorous new house and Susie has been sent to boarding school:

Annie: "Did you see those bills from Susie's new school?"

Lora: "Uh huh. And it doesn't matter."

Annie: "But Miss Lora—"

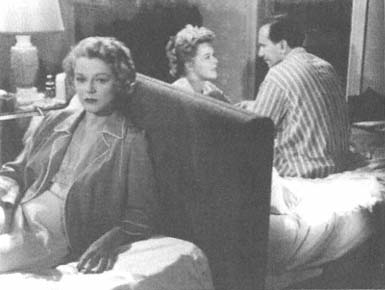

Fig. 11.

Guess who's the good mother in this film? Lana Turner as Lora Meredith

chastises little Susie while good mother Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore)

looks knowingly on in the 1959 Douglas Sirk remake of Imitation

of Life . (Universal Pictures, 1959; photo courtesy of Photofest)

Lora: "No matter what it costs, Susie's going to have everything I missed."

Annie: "From her letters, she misses you more than she'd ever miss Latin. . . ."

As in Mildred Pierce and even Stella Dallas , upward mobility is the province of fathers, not mothers. Later Annie reveals to Lora that Susie is in love with Steve, Lora's own hardworking but unglamorous lover. Lora, in shock, says, "Why didn't I know about this, why didn't she come to me?" Annie replies, "Maybe you weren't around." Lora, of course, gets the message: "You mean I haven't been a good mother." The next scene reiterates the evil career-mother theme, with an angry and love-struck daughter, Susie (played with a sort of wide-eyed adolescent glee by Sandra Dee), further condemning the mom who "gave me everything, but herself." Even Lora's dramatic attempt to make amends with her daughter by sacrificing Steve for the sake of their relationship back-

fires, as Susie pleads with her not to "act" because "I'm not one of your fans." Quite early in the film, when Lora is still living in near poverty and trying to break into the theater, Steve also tells her "not to act" in a fight they were having over her relationship to her work life. The repetition here reinforces the alignment of the daughter with the current patriarchal position on women's labor (its destructiveness and falseness—"acting") and places the mother on the receiving end of their scorn. Lora soon enough sees the light and settles down with the decent, hardworking Steve.

This narrative is contrasted with the story of Annie Johnson and her daughter, Sara Jane, whose desire to be white—and the "passing" that accompanies it—is the other central narrative element in the film. One way to understand this film is that it sets up a good mother/bad mother, good daughter/bad daughter split, with the white daughter and the black mother paired as the virtuous couple. Numerous scenes depict Susie's reliance on Annie as surrogate mother, just as Sara Jane's "passing" is witnessed through her running away to become a dance hall girl, narratively linking her to the white actress mother, whose career is just a sort of "passing" as well. The strange aspect of the film is that, in this case, the daughter who "goes bad" (Sara Jane) is the product of some obviously devoted and healthy mothering. Mildred Pierce blames Mildred for her daughter's badness, but no such blame can possibly be attached to Annie's mothering in Imitation of Life .[28] Rather, Sara Jane's rejection of her mother seems to be the result of a combination of factors: first, the rebellious/alienated teenager theme beloved of fifties filmmakers, second, and more to the point, the effects of a real and present racism. Sara Jane is the way she is not because of Annie's failures as a mother, but because of social failures. Because of the "naturalization" of black maternity (the "mammy" image beloved of Hollywood filmmakers), Annie cannot be condemned as a "bad mother"; that would bring into the narrative the mother/woman dichotomy reserved for white women.

Indeed, both Lora and her daughter are presented as enmeshed within that racist system. Although Lora is depicted as essentially good and loving to both Annie and Sara Jane, there are several significant moments in which the unthinking insensitivity of a white person toward a black person emerges and is critically examined. In one scene, Lora realizes Annie has a life outside her employ and

Fig. 12.

A lovestruck Sandra Dee is less than pleased with mom's announcement

of her engagement to old boyfriend Steve Archer in Imitation of Life .

(Universal Pictures, 1959; photo courtesy of Museum of Modern Art Film Stills Archive)

says, "I didn't know you have friends," to which Annie gently replies, "Miss Lora, you never asked." Even Sara Jane's complacent mother recognizes this insensitivity at one point, and the brutal beating Sara Jane receives from a white boyfriend reinforces the social construction of her rebellion rather than the psychological construction via the mother.

This narrative of maternal beneficence and social injustice places the more traditional narrative of maternal neglect and deprivation on shaky ground because it then sets up two separate rule systems for each mother/daughter pair. If Sara Jane is "bad" because of the way a racist society has treated her, it becomes more difficult to validate Susie's anger and resentment toward her career mother. It almost appears as if Sirk didn't really have his heart in it: the confrontation scene between mother and daughter is mild compared to Mildred Pierce , and after speaking harsh words, the daughter immediately falls into the mother's arms and begs her forgiveness.

The prodigal daughter, Sara Jane, returns to the (white) fold after breaking down at the funeral of her heartbroken mother.

The fact that Lora has decided to give up her career and marry Steve before this confrontation scene reverses the traditional cause and effect narrative movement (bad mother realizes her neglect and repents). If Lora "repents" and settles down prior to the confrontation with the daughter (and thus prior to the full realization of her supposed negligence as a mother), then perhaps this resolution can be read as somewhat self-determined, not wholly in response to her guilt feelings. Thus for many reasons, Imitation of Life is not completely believable as a melodrama of maternal neglect.

The difference between the original version and the 1959 remake is instructive. In the original, Claudette Colbert plays a working mother, carrying on her dead husband's syrup business in a valiant attempt to support her daughter. Her rise to success is predicated on the pancake recipe of Delilah, the obsequious black maid who pleads to work for "Miss Bea" and stays with her until her own death, many years later. The work that propels Miss Bea to the top is thus domestic in origin, beginning in a do-it-yourself diner and moving up to a nationally famous pancake recipe (with Delilah's "Aunt Jemima" picture on the box).

This plot in itself places the film on radically different ground because the 1959 version turns the white mother into a glamorous actress whose neglectfulness as a mother is linked to her own ostentation and narcissism as a (sexualized) "star." Claudette Colbert, as Bea Pullman, is a paragon of virtue; never do we doubt her motherliness or compassion. Even when her daughter unwittingly falls for mother's intended (fish researcher Steven Archer), this is seen less as mother's neglect than as benign circumstance; indeed, they are thrown together when Bea has accompanied Delilah on her search for her runaway daughter.

The differences between the two films can be understood as exemplifying precisely that shift away from discourses centered on extrafamilial realities (race, class) to a psychologically centered melodramatic crisis. Although the racial theme is certainly more vividly and candidly expressed (and, one could argue, more socially responsive) in the 1959 version, it is narratively in the service of the

repetitious discourse of bad working mothers. The 1934 version, although more explicitly racist in its blatant and appalling use of stereotyped images of black women, refuses to indict the working (white) mother and rather foregrounds her working classness (as in Stella ) and her motherly devotion. The figure of the male savior, so crucial to the reconstruction of the domestic unit in the 1959 version (particularly in his alliance with the black mother), is almost incidental in 1934, peripheral to the narrative and, really, to the women's lives.

The 1959 version ends with a soundly reconstructed nuclear family after the tragic death of Annie, but the 1934 film continues past that moment and ends with the white mother giving up the lover (at least temporarily) and remaining bonded with the daughter. The wayward daughter, Peola, whose denial of her blackness and "passing" breaks her mother's heart and causes her death, is returned to the fold and reenrolled in a black college. Both mothers have (successfully) sacrificed for their daughters.

The beginnings are significantly different as well. The earlier version opens with a beneficent image of Bea Pullman lovingly washing and dressing her daughter; the 1959 version opens with Lora Meredith searching wildly for the daughter she has "lost" at Coney Island. It is Annie who "finds" little Susie, thus early on establishing her as the "good (sacrificial) mother" to Lora's self-involved actress/mom. As different as these two versions are, certain aspects remain the same. For instance, all the names of the characters change except that of the male figure, Steven Archer. More important, both films completely occlude the possibility of representing the black woman: she is either a stereotyped, sacrificial mother (sacrificing for her own daughter as well as playing surrogate mother and surrogate husband to the white women) or a stereotyped "tragic mulatto" whose desire to "pass" for white is rarely placed in a context that affords it any real meaning. Although white motherhood becomes problematized with the onslaught of popular psychology and the postwar rush to domesticity, black motherhood remains completely "natural" and assumed to be inevitably beneficent. Lora Meredith plays out the mother/woman split in the narrative, but Annie Johnson is denied one side of this admittedly limited dichotomy. Her sexualized daughter can play it out, although

only on the basis of her "whiteness," itself made more complex by the fact that a white actress actually played that part (unlike in the earlier version).

Susan Hayward, another tortured actress similar in both style and substance to Lana Turner, tried her hand at another mother/daughter melodrama about the theatrical life as one of sin and decadence keeping wayward women from their hardworking husbands. I'll Cry Tomorrow is the rage to riches to rags saga of Lillian Roth, poor daughter of immigrants who is pushed by her striving mother (Jo Van Fleet) to acquire fame and fortune as a stage singer. The film begins by firmly establishing the stage mother theme as mother accompanies young Lillian to an audition, then beats her viciously on the street when she fails to butter up the director as mama instructed. Lillian moves to semistardom (not quite as ostentatious as Lana Turner, but then this film was black and white and directed by Daniel Mann, not melodrama magician Douglas Sirk), and mama is always close by her side, pushing her reluctant daughter forward.

When childhood friend David Tredman shows up in Hollywood, Lillian's thoughts turn to romance, and marriage plans are in the wings. Mother, of course, tries to disrupt the happy couple and invites David over for a little chat. As she tries subtly to get him away from her daughter, he calls her bluff and thereby sets himself up as the voice of male-defined integrity against self-interested (s)mothering in a way reminiscent of Dr. Jacquith's homilies of independence. David says, "You and I want Lillian to be happy. And she wants us to be happy. But we're three different people. Each of us has the right to decide where we belong. Or if we belong at all. Without that there's nothing. Now you may want one thing and she may want another and I may want a third."

David knows what he wants: a "wife who will bawl him out for not being ambitious enough." When Lily walks in, she falls right into place after a brief moment of anguished ambivalence: "Whatever David wants . . . is what I want. Whatever makes David happy makes me happy. You see Mama, I want to be David's wife." As mama pleads with her not to throw it all away, Lily rhapsodizes on the joys of wifedom, the plenitude of her future with David, her desire to be a "real wife."

But it is not to be, and poor Lillian doesn't regain love until the end of the film. David dies, sending Lily into a bout of depression and mother-blame: "You always know what's good for me. How to dance, where to sing, what to wear, who to go out with. So what I'm doing now it's not for my own good. And I'm doing it!" Her anger builds, and her mother leaves in a defeated, martyred sort of way ("All I ever wanted was for you to be happy . . . that's what I want now so maybe it's better . . . if I'm not here for a while").

Lily starts on a downward spiral of booze and parties and ends up marrying a man while drunk, then divorcing him after a year of boozy nights. The next man, who looks to be her savior, ends up marrying her for her money and keeping her hostage as he beats and robs her. After escaping from her tyrant husband, Lily hits bottom, then finally finds her way back to mother. Now a frantic alcoholic, Lily plays cards in her mother's house, begging for booze and flying into rages when it is not immediately forthcoming. The requisite confrontation scene between overinvolved/underinvolved mother and victimized daughter is now played out in its full melodramatic potential. Mother, reluctant to go out and buy more liquor, has been stalling an ever more hysterical daughter. As she finally heads for the door, she breaks and gives her version of their relationship:

Mother: "All right, it's my fault huh? I made you become an actress. You didn't want to. All right. I've been a bad mother. You had to support me. All right, all right, all right—everything! (shaking Lily now) But just this and for once in your life you're going to hear it! You know at all why I did it, do you? No you don't. Do you know what kind of a life I had? Do you know what it was like to live with your father, put up with his mistakes and afterwards to be left with nothing. No money, no career, not young anymore, nothing to fall back on. No you don't. You don't know at all what I tried to save you from. The kind of freedom I never had I tried to give to you by making you Lillian Roth."

Lillian: "So you admit it. You invented Lillian Roth. All right. Now look at me! I said look at me! Don't turn your face away. I'm the looking glass you created to see yourself in. All right, all right see yourself now in me. Look at this ugly picture and

Figs. 13 and 14.

Susan Hayward gets to play yet another drunken ruin in I'll Cry Tomorrow (1955).

This time she plays Lillian Roth, the victimized daughter of a stage mother who plots

to keep her from the man she loves and, predictably, turns her into a needy wreck living

back at home with dear old mom. (MGM, 1955; photos courtesy of Museum of Modern

Art Film Stills Archives)

then get out of here. But keep this ugly picture before your face as long as you live!"

Mother: "It's true. Oh god help me. I owe you this. Every single word of it is true."

Now that the evil done to daughter is out in the open and mother has owned up to it, the prodigal daughter can reclaim the broken mother. She holds her on the couch, saying she didn't mean it, and gets rather apologetic, in a brisk sort of way. Lily leaves the apartment, contemplates suicide in a hotel room, and finds her way to Alcoholics Anonymous and the strong arms of Eddie Arnold, a "survivor" like her. She dries herself out, starts singing again, falls in love with Eddie, and culminates her reclamation with an appearance on "This Is Your Life," telling the world her tortured tale.

Another guilty mom—doomed by her desire to give her all for her little girl—popped up several years earlier in a rather sporty twist on the overinvolved mother paradigm. Ida Lupino's 1951 film, Hard, Fast and Beautiful , is yet one more cinematic rendering of the talented but benighted daughter manipulated by the climbing, striving "stage mother." The film opens with the mother's voice narrating as the tennis whiz daughter steadfastly bangs a ball against a garage door: "From the moment you were born, I knew you were different. . . . I always wanted something better for you and I made up my mind to get it, no matter what I had to do." What she has to do is scheme dishonestly with a rather unscrupulous tennis promoter to propel her innocent daughter to the top, leaving behind the well-intentioned but hapless and weak father and the daughter's honest, working-class boyfriend.

Conniving mom, in a manner reminiscent of later Mommie Dearest scenarios, frames her obviously self-serving martyrdom in terms of giving her daughter all that she never had. In a crucial scene where mom's evil is clearly established, she is in the bedroom she shares with her hopelessly kind husband and informs him, "My

Fig. 15.

Mom may hold the pursestrings of daughter's tennis career, but it's daddy

who holds her heartstrings in Ida Lupino's Hard, Fast and Beautiful . (RKO,

1951; photo courtesy of Museum of Modern Art Film Stills Archive)

daughter's going to have everything, everything I missed. She's going to go places." As she speaks with her husband, they are literally separated by one of the strangest twin bed arrangements to hit the silver screen: the beds are placed head to head so that the supposedly intimate couple does not actually look at each other while they speak. Mother does her nails on one bed, and father first tries to stick up for the daughter and then falls into a pathetic plea: "Every year she was growing up, you were growing away from me. Why, Millie? Can't you love us both?" But in these representations, the love for the daughter must always be at the expense of the love for the father.

After the daughter's predictable rise up the ladder of women's sports, she becomes (predictably) hard and self-serving like her mother. As boyfriend Gordon tells her, "Your mother's done a first class job on you, honey. You're getting to be more like her every day." When Gordon leaves her, she becomes harder and faster (hence the title) and confronts her mother with her duplicity and

unsportsmanlike pursuit of fame and fortune. The daughter briefly tries to emulate the mother's ruthlessness, but she is brought back to life by the efforts of a dying dad and a firm boyfriend who comes to take her away from the high-powered, sleazy world of women's tennis and into the haven of suburban domestic bliss. As she leaves in victory from center court at Forest Hills, she gives the victory cup to mom ("This is yours, you've earned it") and goes off with Gordon. The last shot shows mom alone, at night, watching the garbage blow over the darkened tennis court.

Six years later Lana Turner did a warm-up for her performance in Imitation of Life by playing another working mother neglecting the emotional/sexual life of both herself and her teenage daughter. The notorious melodrama Peyton Place (later to be followed by a television soap opera version) included two mother/daughter pairs—the virtuous Salina (Hope Lange) living in squalor with her mother, who works as a maid for Mrs. MacKenzie (Lana Turner) and her daughter Alison (Diane Varsi). In an early scene (the first between Alison and her mother), the existence of the absent father rears its ugly head. Supposedly, he is dead (a war hero); but because this is a soap opera, he turns out to be a married man with whom Mrs. MacKenzie had an affair. The daughter worships the father she has never seen. When the mother objects to the daughter kissing his picture before she goes off to school, Alison replies, "It's not my fault that he died before I was two." Alison lacks a father—a male presence—and it is this lack that motivates the mother/daughter conflict, as the mother replies angrily, "Stop talking about fathers and husbands and marriage." So an opposition is set up between careerist, unloving, perfectionist, cold mother and daughter's desires for male attention and approval. This is spelled out in a later scene in which mom catches the daughter kissing at a party held in their house:

Mother: "I don't want you to be like everyone else in this town. I want you to rise above Peyton Place."

Daughter: "I don't want to be perfect like you, Mother. I don't want to live in a test tube. I just want to be me. . . . I'd rather be liked than be perfect."

In the ensuing battle, the mother tries to make up by saying that she wants the daughter to fall in love, to meet the right man, and

so forth; but the daughter will have none of it, "You want! Is that all you can say? Well if any man would seriously ask me I'd run away and become his mistress." The daughter's need to be sexually desired is thrown in the face of the mother's fear and denial of her own sexuality. This is reiterated in a later scene where mother accuses daughter of having been swimming nude with a boy:

Alison: "Mother, if you keep this up someday I will do what you keep accusing me of."

Mother: "I wouldn't doubt it. You're just like your father when it comes to sex."

The daughter is again identified with sexuality, freedom, and father, and the mother is clearly the force of repression.

The claustrophobia of the suburban idyll, the endless repetition of actions and reactions, is expressed through the mother/daughter relationship. Alison confides in the maid Nellie after a fight with her mother in much the way Susie confided in the maid Annie when her working mother was "unavailable":

Alison: "Nellie, you've been both a daughter and a mother, which one is worse?"

Nellie: "Being a mother."

Alison: "Why?"

Nellie: "You find yourself doing the same thing you hated your own mother and father doing."

Alison: "That's very interesting. Somewhere along the line doesn't somebody get intelligent and realize that the children have to grow up their own way?"

Here are shades of Dr. Jacquith's theme of "growing free and blossoming." Yet these ideas of letting children grow up "their own way" emerge in the context of a society in which the professionalization of motherhood and the rise of the expert have inserted themselves into every nook and cranny of social life: "Whether or not all Americans read or believed the professionals, there can be little doubt that postwar America was the era of the expert. . . . Science and technology seemed to have invaded virtually every aspect of life, from the most public to the most private. Whether in medicine, child rearing, or even the intimate areas of sex and marriage, ex-

pertise gained legitimacy as familiar, 'old-fashioned' ways were called into question."[29]

As Clifford Clark and others have noted, there existed in the fifties competing discourses of maternal incompetence and natural maternal functioning that make it difficult to decipher the dominant ideology of maternal behavior: "The tension between self-sufficiency and ineptitude which was expressed in Dr. Spock's contradictory emphasis on both personal self-reliance and professional expertise, placed women in an ambivalent position."[30] Indeed, the venerable town doctor in Peyton Place is the voice of professional authority: he advises the victimized Salina, reveals the truth of her rape by her stepfather, and informs Mrs. MacKenzie that it isn't healthy to have only one child.[31]

The mother eventually blurts out her confession (the daughter's illegitimacy), and the daughter leaves Peyton Place and moves to "The City," only to be reunited with her mother when mom proves her "goodness" at Salina's trial for accidentally killing her drunk stepfather. The reunion, though, occurs only after a man (the handsome new schoolteacher) has broken down mom's icy reserve, and she becomes an available object of the gaze. The ending is thus similar to Imitation of Life in that the mother and daughter can be brought back together only when a man enters the picture and "balances it out," thus legitimating the connection, now safely ensconced in a nuclear-family context, and eliminating any suggestion of self-defined mother/daughter intimacy.

Containing the Crisis, Domesticating Dissent

In many of the films of the late fifties, in contrast to the dominant images of mothers and daughters in the forties, the women are reunited by film's end. Whereas Veda is arrested and Charlotte gets rid of her mother by a convenient death, these later films leave us with the sense of a relationship maintained, albeit with chastened mothers. This should not be surprising, given the dominance of family ideologies in the fifties. The drastic separation entailed in a film like Mildred Pierce implied trouble in the domestic nest. But the vision of familial harmony produced by the culture industry and

Fig. 16.

Lana Turner stars as the repressed working mother who fears that her

acting-out daughter will repeat her own (sexual) mistakes in the suburb

an potboiler Peyton Place . (20th Century-Fox, 1957; photo courtesy of

Photofest)

supported by government policies simply could not tolerate so drastic a rift in the domestic landscape.[32] In both Now, Voyager and Mildred Pierce , the families we are left with at film's end are strange and fractured: Charlotte becomes the keeper of her lover's daughter, suppressing her own sexuality in the service of this awkward arrangement. Mildred is reunited with her first husband, Burt, but is rendered childless—one daughter lost to her neglect and another to her obsessiveness. Neither is a simple vision of a domestic idyll.

Although Peyton Place revealed the underside of the suburban paradise (tellingly set right at the beginning of the U.S. entry into World War II), it ended up arguing that the family can be internally cleansed. By film's end, mother and daughter walk into their beautiful bourgeois home together as father/lover figure (the schoolteacher) and Alison's boyfriend look on proudly. You can almost

hear them saying, "Gosh, it's good to have our girls back together again!"

Images of mothers and daughters in the forties, for all their meanness, expressed and explored the turmoil of a world in crisis, a world amazed at the horrors of fascism and unsure of what the future would bring. But in the fifties, popular culture was passionately enjoined in the effort to acclimate and orient Americans to the "brave new world" of mass consumption, tract housing, and ideological homogeneity. Peyton Place could expose the contradictions, but it could not let them exist. Imitation of Life could present mother/daughter conflict, but it had to reestablish a familial harmony by film's end.

Even the conflicts between mothers and daughters that went on in both films of the fifties seem more like a rather benign generational struggle than a profound psychological disharmony, reflecting perhaps the popularization of "youth rebellion" as a legitimate social category. When Alison threatens to run off with a lover, we can picture the mothers in the audience smiling gently at her youthful naiveté, sure that, as the psychologists say, this is only a stage she is going through. And Susie's "you've given me everything but yourself" speech is shot through with a sort of humor, as when she asks her mother pertly if she has worded her college application correctly.

The rifts between mothers and daughters could now be managed, worked out, rectified. But this working out was intimately tied to the reconstruction of the harmonious (patriarchal) nuclear family. Representations of the mother/daughter relationship in the postwar years presented a vision of an endlessly malleable nuclear family, able to withstand problems and disagreements, secure in the knowledge that everything can be worked out eventually. Although conflict between mother and daughter remained central to the narratives, it was interpreted not so much as the imposition of the neurotic mother on the victim/daughter, but rather as part of a "life stage" or even generational rebellion. As in the films of the mid and late forties (Mildred Pierce, Now, Voyager ), psychology eclipses class as a mediating theme. But the type of psychological offering here is a bit different, a psychology now searching for continuity and conformity, resolution and adjustment.

So the mother and daughter are reunited in many of these fifties images; yet it is a problematic reunion. Without acknowledgment of class and history, the reunion is rather sterile. More important, the reunion in both films discussed here depends on the reconstruction of the nuclear family and the reestablishment of a dominant male presence, a reestablishing that is also performed in terms of genre. Perhaps this return of the male presence signals the end to the female-centered "women's films" and a resurgence of more male-defined generic formulas, particularly in the "rebel" films of the fifties and early sixties.

The fifties and early sixties remain marked by the rigorous attention of popular culture to an explicit and rarely wavering ideological agenda of familial harmony and feminine containment. Turning again to "Father Knows Best" we see how an unambiguous ideology permeates the very fabric of cultural design. In a 1958 episode entitled "Medal for Margaret," the subject is trophies and medals. As father and the kids busy themselves building a case to hold their symbols of achievement, mother, who has none, is made to feel lacking, yet assures her concerned brood that she is "perfectly happy cooking all of the meals to keep all you champions hale and hearty."

But, to keep the family happy, Margaret secretly takes up fly casting in order to compete in a women's contest and thus win the admiration of her husband and progeny. True to sitcom logic, Margaret breaks her arm and is unable to compete in the contest. Finding out her plan, her touched family entertains her with a "This Is Your Life, Margaret Anderson" ceremony. Each member of the family recounts an event in which resourceful and reliable mother/wife Margaret has exhibited exemplary maternal behavior. Eldest daughter Betty begins by recalling the time when she was nine years old and her mother valiantly dashed off a new, prize-winning costume after she had fallen and ruined hers on her way to a party: "I thought that she was the greatest, smartest mother in the whole world. Of course now that I'm older I'm sure of it. And so, Mrs. Anderson, I award you this plaque for most valuable mother," giving her a frying pan with "Most Valuable Mother" written on it. Each child continues—"Boy's best friend," and so forth—and father finally pops in with a medal for "being the best darn wife I ever had."

First Margaret is mocked for her lack of achievement. Then, when she does try to learn a skill, she is terrible at it and, finally, taken out of the running. Ultimately, Margaret is compensated for her lack of official recognition by the recognition of her family: her maternal/wifely nurture and caretaking have allowed her family to excel. This vicarious success, the show implies, is all that she should ever need or want.

But mother's caretaking and functioning (as the positivist sociologists would have it) is at the same time presented as inadequate to the task of preparing her children for the major moral and social issues that will confront them in their adult years: "Philip Wylie's presence in Fifties television is felt not in a preponderance of violent or evil mothers; rather, the programs 'solve' the 'problem' of mother's all-powerful and harmful influence within the family by decisively reconfiguring the father as the crucial molder of his children's psyches, while simultaneously suggesting that the mother is fundamentally inadequate to this and other familial and household tasks."[33] "Father Knows Best" is quite literally what it says it is: mother is the family (she is intimately aligned with the domestic) yet she is strangely insignificant. Here again is that double message of the fifties: extolling the virtues of motherhood and domestic femininity while promoting fathers as primary socializers. The background to this seemingly antinomous message is the lingering scent of the rabid misogynists, Wylie, Strecker, Lundberg and Farnham, and others.

In a 1959 episode entitled "Kathy Becomes a Girl," the role of the father as both the figure of knowledge and moral guidance and the educator into appropriate femininity is made explicit. In a reversal of what would typically have been a dialogue between mother and daughter, father now supplants mother as the one most able to educate their daughter in the realities of adult femininity. The episode begins with mother's concern about youngest daughter's tomboyish behavior ("Kathy, don't you think you're getting a little old to be wrestling boys and playing football?"). Kathy's initial resistance ("What else is there to do?") quickly turns into concern over her lack of girlfriends and her status as "oddball." Mother informs her that "there comes a time when girls like girls who act more, well, more like girls." Kathy continues, objecting, "You mean I should act the way they do and be a stuffed shirt?" Mother replies,

"No! Just be a normal, average girl." Kathy replies, "I don't think I'm the type." Mother here is able to express the desire for conformity but has not the power to create it; that job is left to father.

The inculcation of appropriate femininity into Kathy is painful to watch. Kathy's inappropriate behavior is signified by her physicality: roughhousing with boys and swinging and hugging her girlfriends. Part of the breaking of Kathy, of constructing the feminine in a little girl, involves restricting the body and producing a repertoire of "feminine" deceit and manipulation.

This episode of "Father Knows Best" puts to rest any doubts concerning the authenticity of Simone de Beauvoir's comment that "woman is made, not born." The entire family becomes engaged in making a woman out of Kathy. When Kathy is ignored by her girlfriends as a party is being planned, the tension heightens, and father legitimizes mother's exasperated (and rather comical) concern by pointing out the implications of this problem for Kathy's "development": "If she feels rejected at school this can become a big problem for her. We've got to find a solution." When sister Betty suggests that the solution lies in a gender switch, Kathy runs down the stairs to concur with her joking sister, "I wish I was a boy!"

Although mother buys Kathy a frilly dress in the hopes that it will "encourage her to be more careful and ladylike" and big sister initiates her into the world of feminine appearance ("I'll turn her into a girl if I have to black her eye doing it"), father finally gets through to the still reluctant Kathy in a little talk they have on the steps. The reference point in his pitch is mother; he's going to let Kathy in on the little tricks mother uses that make her so wonderful: "Oh, I mean cute things. Like, uhh, being dependent, a little helpless now and then, expecting me to take over. You see, men like to be gallant. All you have to do is give them the opportunity." He convinces Kathy that little tricks are a part of being a woman, and she concludes, "We girls have got it made. All we have to do is sit back and be waited on." But father is quick to point out (and here is the nod to the reality of women's lives, including participation in the labor force) that "it's very important for a girl to be capable and self-sufficient." But Kathy continues to get it wrong, and more work is needed to set her straight:

Kathy: "I am! I can beat Eroll wrestling any day!"

Father: "Worst thing you can do. Never try to beat a man at his own game. You just beat the women at theirs."

Fig. 17.

All eyes (and hearts and minds) are on dad in that classic of domestic

sitcoms, "Father Knows Best." (CBS; photo courtesy of Photofest)

Kathy: "I'll remember Daddy. But are you sure it'll work?"

Father: "Your mother's worked it on me for over twenty years."

In the end, Kathy accedes to her feminization. She successfully seduces the boys by acquiring the trappings of "girlness" and employing the "womanly" arts of deception. The final scenes show her rendered prone and helpless by a (false) broken ankle and thus rewarded by the attention of admiring boys. Kathy wins over the girls as well, who now find in her a successful sister who is finally able to attract the sought-after males.

This induction into appropriate femininity is also the subject of an appalling article written in 1956 by Constance Foster entitled "A Mother of Boys Says: Raise Your Girl To Be a Wife." The author here is clearly angry at the "confused" roles in contemporary society and wants to get wayward women back on the right path to wife and motherhood: "The one essential qualification for a satisfactory daughter-in-law is the ability to be a real woman and like it. For such a girl having children is the most natural thing in the world because it's what everything is all about." Foster cites Farnham and

Lundberg in stating her case against willful mothers who would lead their daughters into the never-never land of female independence: "Long before it's time for Mom to help plan the wedding or Dad to give the bride away, it's time to be raising a future wife in your home. Because wives aren't born—they are made. Your daughter is born a female, but she has to learn to be feminine."[34]

This strange twist on de Beauvoir, like its "Father Knows Best" counterpart, encourages mothers to be diligent in their education of their girl children. Bolstering dads seems to be a principal ingredient in the construction of a wife: "Sometimes a mother harms her daughter's chances of future happiness in marriage by deprecating men in general and the girl's father in particular. If she is the one who 'runs' the family she then gives her daughter the feeling that men need to be managed." Those important "inner patterns of femininity" are almost solely contingent on daughter's worship of father and mother's ability to access those for the daughter: "I hope my daughters-in-law are lucky enough to have Dads who rave over their first fumbling attempts to bake a cake and make dresses for their dolls. The fonder they are of their fathers, the better they will be someday for my sons."[35]

Mothers of daughters are not only urged to prepare them for the dubious distinction of wife/helpmate/mother but are also often informed of the intractability of generational struggle and the necessity of remaining forgiving and accessible throughout. In an article on how to be popular with your daughter (a very common theme in the fifties age of conformity), Marjorie Marks urges mothers to be endlessly malleable in relation to their daughters' teenage angst: "Never be too busy when Daughter talks or too pressing if she is reticent. It's normal procedure for her to prefer Friend Irma to yourself as confidante. This is proof that the apron strings are lengthening as they should be. Some day she will come back of her own free will. A girl's best friend is her mother—on request only."[36]

Yet Jo Wagner is not so sure that what goes around will, in fact, come around: "There is a theory that a teenage girl, once she herself has grown up and becomes the mother of a teenage girl, will say, 'Mother was right!' Comforting, that theory—if you can subscribe to it. I can't. I am sure that she will do no such thing. My daughter will look at her daughter in amazement and consternation. She'll wonder, What is the matter with kids these days? She'll be saying, 'Now when I was your age—'"[37]

One thing remains clear in both these statements and the issues previously discussed: the fifties continued the process of constructing the mother/daughter relationship as a series of double bind discourses. On the one hand, mothers are to be endlessly available and responsive to the caprices of their teenage daughters. Indeed, the inevitability of generational struggle (or, more accurately, "irritation") is produced here as a natural category and a prerequisite for development (lengthening of those apron strings as they should be). The theme in many women's magazine articles was one of a sort of benign tolerance toward rambunctious daughters. Yet mothers were simultaneously condemned for not being attentive and diligent enough with their kids and thus urged to exert a more substantial maternal influence on both their wayward youth and their wayward society.

The double binds continue. Mrs. Anderson is held up as the epitome of well-adjusted womanhood; yet she is not even deemed competent enough to teach her daughters the "necessary" lessons of womanhood. Mothers are to initiate their daughters into appropriate femininity (turn them into wives, as the article states), but how can Mrs. Anderson reproduce herself if dad has taken over that job as well? Mothers continue to be held responsible for their daughters' psyches and personalities yet are given little narrative power to make that responsibility meaningful.