The Federal Framework

Urban renewal was created by the federal government. As a result, the roles and capabilities of the participants were strongly influenced by federal laws, regulations, and policy determinations. The Housing Act of 1949 sought to halt the spread of "slums and blight" through slum clearance and redevelopment. Under Title I of the 1949 legislation, federal aid would be given to cities to encourage clearance of blighted areas, and redevelopment of the cleared areas for housing, industry, or other purposes. The financing arrangements assured that private developers as well as public agencies would be actively involved in carrying out the purposes of the new program. A local public agency would purchase and clear the land, and provide sewers and other facilities. The public agency then would sell or lease the land to a developer, who would construct housing or other mutually agreed-upon projects. And the federal government would repay the city for two-thirds of the net cost of the total project package.[4]

In effect, Title I of the Housing Act of 1949 required renewal projects to meet the perceived goals of private developers, as well as those of local governments. Federal insistence on close cooperation between developers and public agencies resulted partly from congressional reluctance to allocate large amounts of public funds directly to such a vast field—in contrast, for example, with the reliance on direct public construction in the more narrowly defined public housing program. This reluctance to engage in massive government construction was reinforced by intensive lobbying by the housing industry, whose demands were bolstered by the nation's long tradition of private action in constructing housing, industrial plants, and office buildings.[5] As a result, governmental action in urban renewal has been much more actively influenced by the preferences of specific private firms—particularly large-scale developers capable of undertaking renewal projects—than has been the case in, say, the development of the regional highway network. And the independent role of governmental actors in shaping re-

[3] Most close observers concur with this overall assessment of the impact of the urban renewal program on the pattern of settlement. For the New York region, see Robert C. Wood, 1400 Governments (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1961), pp. 155 ff. For more general assessments, see Charles Abrams, The City Is the Frontier (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), Chapter 9; and the commentators whose views are collected in James Q. Wilson, ed., Urban Renewal: The Record and the Controversy (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1966).

[4] For a detailed discussion of the evolution of federal urban renewal legislation, see Ashley A. Foard and Hilbert Fefferman, "Federal Urban Renewal Legislation," in Wilson, Urban Renewal, pp. 71–125. The basic operation of the urban renewal program is explained in William L. Slayton, "The Operation and Achievements of the Urban Renewal Program," in Wilson, Urban Renewal, pp. 189–229; Slayton, at the time, was head of the Urban Renewal Administration in the U.S. Housing and Home Finance Agency.

[5] See Scott Greer, Urban Renewal and American Cities (Indianapolis, Ind.: Bobbs-Merrill, 1965), pp. 17 ff.

newal programs is more difficult to sort out from other influences than is the case, certainly, with mass transportation, or suburban zoning.

Before any portions of the urban landscape could be cleared and redeveloped, the differing priorities of private developers, federal agencies (the Federal Housing Administration and the Urban Renewal Administration), and the local renewal authority would have to be reconciled. Initially, cities sought to use urban renewal programs to clear slums and replace blighted housing with moderately priced homes. Newark's experience was typical. The staff of the Newark Housing Authority (NHA) perceived slum clearance under Title I primarily as a means of providing middle-class families with new apartments. But NHA officials soon learned that unless a private firm could make a profit on middle-income housing, "no redeveloper would buy the site," and "no FHA official would agree to insure mortgages for construction there."[6] Developers invariably demanded choice sites and higher rents than those originally planned by NHA. In the face of the constraints imposed by the requirements of private involvement, NHA shifted its attention to less blighted areas and a higher-income clientele for the new apartments. Under skillful leadership that maximized the authority's autonomy from much of the local political system, NHA pursued its revised goals with considerable success. As Harold Kaplan notes, "high-priced apartments on sites immediately surrounding the central business district" rather than the original goals of "slum sites" and "moderate rents" were the principal product of Newark's first decade of urban renewal.[7]

New York City's Slum Clearance Committee also quickly discovered that the economics of urban renewal under Title I facilitated the construction of luxury apartments and other high-value projects rather than the middle-income units initially promised by the program. Under the aggressive direction of Robert Moses, New York launched a monumental Title I program which by 1960 had redeveloped more land than all other cities in the nation combined. In place of moderately priced housing in the cleared neighborhoods rose luxury apartment buildings, a $22 million exhibition hall, office buildings, hospital and university facilities, and the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.

Out of the framework provided by the Housing Act of 1949 came a set of relationships among three major participants. One was the federal Housing and Home Finance Agency—which in 1965 became the Department of Housing and Urban Development—whose officials would have to concur in the plans of any project before federal funds could be reserved or paid to the city. The second was the private developer, whose willingness to purchase the land for specified uses would be required if any renewal was to occur under Title I. The third was the local public agency, which under the federal law could be the city government itself or any agency designated by the city. In order to avoid local debt limitations, as well as to combine the renewal function with existing public housing responsibilities, the local agency chosen was frequently a public authority.

[6] Harold Kaplan, Urban Renewal Politics: Slum Clearance in Newark (New York: Columbia University Press, 1963), p. 16.

[7] Ibid., p. 25.

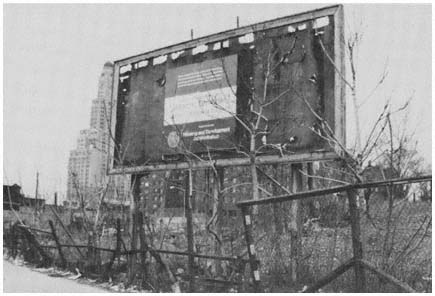

The site of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal

Project in Brooklyn, one of a number of renewal

schemes in the region that never progressed

beyond the clearance stage.

Credit: Michael N. Danielson