9—

Urban Renewal: Political Skill and Constituency Pressures

One major strategy to overcome the obstacles to concentrating resources in the older cities is the use of semiautonomous functional agencies. One of the region's most influential governmental institutions—the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority—was organized as an independent functional agency operating entirely within the boundaries of New York City, as was the New York City Transit Authority.[1] The use of such functional agencies within older cities has been particularly extensive for public housing and urban renewal. All of the public housing in the region's older cities has been developed by housing authorities. Functional agencies of one kind or another, usually operating with considerable financial and policy independence from city hall, also undertook urban renewal in the cities, with the same agency often responsible for both public housing and redevelopment.

In this chapter we focus on urban renewal in the older cities, and in particular on the ability of renewal agencies to concentrate resources on their development objectives. Although the federal urban renewal program largely expired in the mid-1970s, urban renewal deserves serious attention in any examination of the impact of government on the distribution of jobs and residences in metropolitan regions.[2] For a quarter of a century the renewal program was the major source of funds, plans, and programs for the revitalization of older cities. Through urban renewal and associated programs, the region's cities sought to redevelop their commercial centers, augment the supply of high-quality housing within their boundaries, stimulate economic development, and otherwise increase their share of jobs and better-off families in the region. Taken as a whole, urban renewal has had less impact on the distribution of jobs and residences than the region's transportation programs and zoning policies. Urban renewal has, however, exerted

[1] As indicated in Chapter Seven, in 1968 both Triborough and the NYC Transit Authority were incorporated into the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, an agency whose jurisdiction reached far beyond the boundaries of New York City.

[2] Federal grants for urban renewal were consolidated into the community development block grant program by the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974. Henceforth, funds for slum clearance and rehabilitation of cleared areas were no longer allocated by Congress and distributed by the Department of Housing and Urban Development to local urban renewal agencies on the basis of project application. Instead, renewal activities were funded by city governments out of their community development block grants, along with a wide range of other community and housing investments that can be financed by the federal block grants.

an important influence in some of the region's cities by modifying "private market" decisions regarding the location of office buildings, apartments, and other development.[3]

The Federal Framework

Urban renewal was created by the federal government. As a result, the roles and capabilities of the participants were strongly influenced by federal laws, regulations, and policy determinations. The Housing Act of 1949 sought to halt the spread of "slums and blight" through slum clearance and redevelopment. Under Title I of the 1949 legislation, federal aid would be given to cities to encourage clearance of blighted areas, and redevelopment of the cleared areas for housing, industry, or other purposes. The financing arrangements assured that private developers as well as public agencies would be actively involved in carrying out the purposes of the new program. A local public agency would purchase and clear the land, and provide sewers and other facilities. The public agency then would sell or lease the land to a developer, who would construct housing or other mutually agreed-upon projects. And the federal government would repay the city for two-thirds of the net cost of the total project package.[4]

In effect, Title I of the Housing Act of 1949 required renewal projects to meet the perceived goals of private developers, as well as those of local governments. Federal insistence on close cooperation between developers and public agencies resulted partly from congressional reluctance to allocate large amounts of public funds directly to such a vast field—in contrast, for example, with the reliance on direct public construction in the more narrowly defined public housing program. This reluctance to engage in massive government construction was reinforced by intensive lobbying by the housing industry, whose demands were bolstered by the nation's long tradition of private action in constructing housing, industrial plants, and office buildings.[5] As a result, governmental action in urban renewal has been much more actively influenced by the preferences of specific private firms—particularly large-scale developers capable of undertaking renewal projects—than has been the case in, say, the development of the regional highway network. And the independent role of governmental actors in shaping re-

[3] Most close observers concur with this overall assessment of the impact of the urban renewal program on the pattern of settlement. For the New York region, see Robert C. Wood, 1400 Governments (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1961), pp. 155 ff. For more general assessments, see Charles Abrams, The City Is the Frontier (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), Chapter 9; and the commentators whose views are collected in James Q. Wilson, ed., Urban Renewal: The Record and the Controversy (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1966).

[4] For a detailed discussion of the evolution of federal urban renewal legislation, see Ashley A. Foard and Hilbert Fefferman, "Federal Urban Renewal Legislation," in Wilson, Urban Renewal, pp. 71–125. The basic operation of the urban renewal program is explained in William L. Slayton, "The Operation and Achievements of the Urban Renewal Program," in Wilson, Urban Renewal, pp. 189–229; Slayton, at the time, was head of the Urban Renewal Administration in the U.S. Housing and Home Finance Agency.

[5] See Scott Greer, Urban Renewal and American Cities (Indianapolis, Ind.: Bobbs-Merrill, 1965), pp. 17 ff.

newal programs is more difficult to sort out from other influences than is the case, certainly, with mass transportation, or suburban zoning.

Before any portions of the urban landscape could be cleared and redeveloped, the differing priorities of private developers, federal agencies (the Federal Housing Administration and the Urban Renewal Administration), and the local renewal authority would have to be reconciled. Initially, cities sought to use urban renewal programs to clear slums and replace blighted housing with moderately priced homes. Newark's experience was typical. The staff of the Newark Housing Authority (NHA) perceived slum clearance under Title I primarily as a means of providing middle-class families with new apartments. But NHA officials soon learned that unless a private firm could make a profit on middle-income housing, "no redeveloper would buy the site," and "no FHA official would agree to insure mortgages for construction there."[6] Developers invariably demanded choice sites and higher rents than those originally planned by NHA. In the face of the constraints imposed by the requirements of private involvement, NHA shifted its attention to less blighted areas and a higher-income clientele for the new apartments. Under skillful leadership that maximized the authority's autonomy from much of the local political system, NHA pursued its revised goals with considerable success. As Harold Kaplan notes, "high-priced apartments on sites immediately surrounding the central business district" rather than the original goals of "slum sites" and "moderate rents" were the principal product of Newark's first decade of urban renewal.[7]

New York City's Slum Clearance Committee also quickly discovered that the economics of urban renewal under Title I facilitated the construction of luxury apartments and other high-value projects rather than the middle-income units initially promised by the program. Under the aggressive direction of Robert Moses, New York launched a monumental Title I program which by 1960 had redeveloped more land than all other cities in the nation combined. In place of moderately priced housing in the cleared neighborhoods rose luxury apartment buildings, a $22 million exhibition hall, office buildings, hospital and university facilities, and the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.

Out of the framework provided by the Housing Act of 1949 came a set of relationships among three major participants. One was the federal Housing and Home Finance Agency—which in 1965 became the Department of Housing and Urban Development—whose officials would have to concur in the plans of any project before federal funds could be reserved or paid to the city. The second was the private developer, whose willingness to purchase the land for specified uses would be required if any renewal was to occur under Title I. The third was the local public agency, which under the federal law could be the city government itself or any agency designated by the city. In order to avoid local debt limitations, as well as to combine the renewal function with existing public housing responsibilities, the local agency chosen was frequently a public authority.

[6] Harold Kaplan, Urban Renewal Politics: Slum Clearance in Newark (New York: Columbia University Press, 1963), p. 16.

[7] Ibid., p. 25.

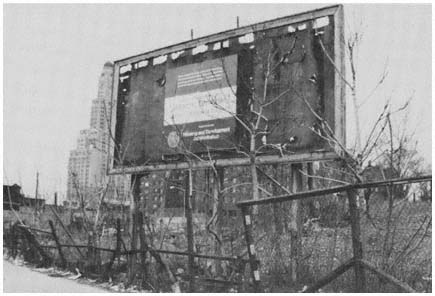

The site of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal

Project in Brooklyn, one of a number of renewal

schemes in the region that never progressed

beyond the clearance stage.

Credit: Michael N. Danielson

Elements of Success and Failure

In order to make an impact on land use patterns in its city, the renewal agency had to forge effective relations with both federal officials and developers. This required the local agency to be able to concentrate resources on specific projects that would satisfy the other key participants. To achieve this goal, urban renewal agencies needed some insulation from the mayor's office and from other city elected officials and local constituencies, all of whom were likely to press in diverse directions, complicating relations with Washington and with private developers. In addition, leadership skills were required to seek out the opportunities and constraints inherent in Title I, and to deal with other elements of the city political system, both at city hall and in the affected neighborhoods.

In this section we explore the interplay of these factors in two of the region's older cities, Newark and Trenton, which had very different experiences with the urban renewal program during its first dozen years. Our comparison focuses on the period from 1949 to the early 1960s, when both cities had housing authorities serving as their urban renewal agencies. Thus two public authorities are compared, and the relative impact of their urban renewal efforts and the factors that underlie their differential impacts are examined. "Impact" on development is measured in terms of the number of urban renewal projects completed or initiated during the period, the percentage of city

land directly involved in authorized projects, and federal funds expended or allocated in the two cities.[8]

In these terms, the differences between the Newark Housing Authority and the Trenton Housing Authority (THA) are dramatic. The Newark agency had completed two renewal projects by 1961, and had received federal grant approval for 10 additional projects. Trenton's housing authority had received funding for only two projects, and neither had been completed. The Newark projects encompassed nearly 1,000 acres, or close to 7 percent of the city's land area.[9] The Trenton total was 133 acres, about 3 percent of the city. Even greater were the differences in federal urban renewal funds, both expended or reserved. By 1961, the Newark Housing Authority's total was more than $60 million, placing it in the nation's top 10 renewal agencies in terms of total federal funds received. Trenton, on the other hand, had been allocated only about $2 million. Newark's population was about four times that of Trenton, so Newark's per capita federal funds were approximately seven times as large as those for Trenton.[10]

In accounting for the very different impact of urban renewal in the two cities, areal scope and functional breadth are not helpful variables. Both the Newark Housing Authority and the Trenton Housing Authority operated within the boundaries of their cities, and their functional scopes were similar, with each agency responsible for urban renewal and public housing. Nor were differences in "objective" need for renewal projects significant, since deteriorated commercial and residential structures were widespread in both cities. The two agencies also were similar in their fairly high degree of political and financial independence. Commissioners of both authorities were appointed by the mayors, but they all were private citizens rather than officials of other city agencies. The federal government was the primary source of funds, which gave the agencies potential leverage in obtaining the necessary one-third matching funds from their city governments.[11] On the other hand, neither of these renewal authorities could match the financial independence—in relation to local and state governments—of the highway

[8] Similar measures of impact are used by Wood, 1400 Governments, pp. 155 ff; Kaplan, Urban Renewal Politics, pp. 2 ff; and Raymond Vernon, Metropolis 1985 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1960), pp. 142 ff. It would also be possible to include other factors in an assessment of impact—for example, the effect of the urban renewal program on economic development in the city. Because of problems of definition and difficulties in sorting out the interrelated causal factors, we do not include these measures here. We are not arguing, however, that these indices, or even broader measures of impact on economic development, are definitive ways of measuring whether an urban renewal agency is "successful," either in terms of the broad objectives stated in the Housing Act of 1949 or other social welfare goals. At this point, we are simply concerned with the following: When two agencies are created with similar overall goals, project objectives, and organizational structures, what factors account for the differences in the ability of the two agencies to achieve their purposes?

[9] The proportion of Newark's city-controlled land that was involved in urban renewal was even greater, since the Port of New York Authority uses about 20 percent of Newark's land area for Newark Airport and other facilities.

[10] The totals are calculated from the annual reports of the two authorities. See also U.S. Housing and Home Finance Agency, Urban Renewal Administration, Urban Renewal Project Directory (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1962).

[11] The argument was often made in these cities as in others that to obtain two dollars in outside funding for every one dollar in local money was an "efficient" and attractive way to use local funds.

agencies, where the proportion of federal funds reached nine-to-one in the interstate highway program.

What was distinctly different between the Newark and Trenton agencies was the political skills of renewal officials in the two cities, particularly in their ability to handle constituency demands. Leadership and constituency factors were crucial to the contrasts in program results of the two authorities. These factors can usefully be compared through a brief review of the development of each of the agencies.

Conflicting Pressures in Trenton

The Trenton Housing Authority was created in 1938 to construct public housing under the federal Housing Act of 1937. During the next 10 years, THA built three projects. In constructing its first two projects, the authority was criticized by protest groups involving black and white residents of the designated areas, was attacked for its decisions by both Trenton newspapers, found its plans temporarily halted by a vote of the city council, and finally built the housing projects only after the reluctant intervention of the federal housing administrator. Underlying these constituency problems was the initial attempt by THA to exercise its powers in a truly independent fashion. Sites for public housing had been chosen by the staff, the decisions based mainly on whether the land was vacant and land values low, without any negotiation with city leaders or neighborhood groups prior to public announcement. As Duncan Grant concludes, "THA's early years demonstrated its inability to accommodate opposing interests through private, covert negotiations, and thereby to maximize its chances for success in the public housing arena."[12]

When the federal urban renewal program was initiated in 1949, the Trenton Housing Authority was designated the city's Local Public Agency (LPA) for urban renewal. The first project, redevelopment of the Coalport Yards, was announced in 1952, with public support from the mayor and the city's daily newspapers. Relocation and clearance proceeded slowly, however, and demolition of the last buildings was not completed until six years later. During this period, THA experienced difficulties in its relations with Washington and with the city government. At one point, the housing authority found itself in violation of federal requirements regarding the number of professional planners on its staff. Progress on Coalport was also delayed while THA stumbled through negotiations with city agencies regarding complex technical problems relating to ownership and improvement of sewers, and other public facilities in the urban renewal area. Then, once the land was cleared, THA was unable to enlist enough private developers to complete renewal. In the summer of 1958, THA announced that 20 firms had shown a serious interest in Coalport. But this interest evaporated as commitments were sought. By 1961 only two commercial firms had signed contracts, and most of the land was still without prospective users.

Meanwhile, in 1955 THA had proposed a second renewal project for the Fitch Way area, which included about 100 acres near downtown Trenton. The

[12] M. Duncan Grant, "Housing Authority Politics in Trenton and Newark," Senior Thesis, Princeton University, April 1972, p. 67. The analysis of the Trenton Housing Authority draws particularly on the perceptive discussion in Grant's research paper.

mayor, however, disagreed with the scope of the proposal, urging that it be expanded to encompass planning of the entire downtown area. The authority's commissioners found themselves divided on whether to broaden the project area, and activity on the project largely ceased for nearly a year. In 1957 the federal Urban Renewal Administration threatened to cut off all federal planning funds for the project if THA did not move forward. Early in 1958, the city government expressed its displeasure with the authority's inaction by taking the Fitch Way project away from THA, leaving the agency responsible only for Coalport. While unhappy with the action of the city commissioners,[13] THA staff also felt relieved. Already having difficulty carrying out Coalport, and lacking vigorous leadership and effective relationships with the city government, private developers, and the federal Urban Renewal Administration, THA officials were on balance glad to be free of the complex political and economic problems of the Fitch Way-downtown area.

City Hall found itself no better able to make progress with Fitch Way than THA, however. After a year the city commissioners returned the project to the authority, which proceeded to hold a blight hearing. But THA was soon torn by dissension within its ranks, as one member of the authority charged the agency with delay, waste of funds, and general incompetence. A group of local businessmen joined in the attack, urging that the city remove THA from all responsibility for urban renewal. The mayor agreed and the city fathers in 1960 ended the authority's role in the Fitch Way and future urban renewal activities. When THA was unable to produce firm contracts with developers for the use of land in the Coalport renewal area, that project also was taken from the agency in 1963. Thus, weak leadership cost THA whatever opportunity urban renewal provided for a role in shaping development in Trenton. Fourteen years after the bright beginnings of Title I, the authority was back at "square one"—limited to providing and maintaining public housing for the city.

Building an Autonomous Base for Renewal in Newark

A striking contrast is provided by the Newark Housing Authority's renewal strategies and negotiations during the same period.[14] Like its Trenton counterpart, NHA was created in 1938 to construct and manage public housing projects. During the next decade it maintained close and effective relations with City Hall, and constructed seven projects without encountering any significant opposition. This relatively positive record—compared with the turbulent early years of THA—was somewhat marred by charges of political interference in site selection and awarding of contracts in 1948, and NHA's executive director resigned under fire.[15]

[13] At the time both Trenton and Newark employed the commission form of government, with city commissioners exercising both legislative and executive authority.

[14] The discussion of the Newark Housing Authority in this section draws primarily on Kaplan, Urban Renewal Politics . See also David Marshall, "Urban Renewal in Newark," Senior Thesis, Princeton University, April 1971: and James Schoessler, "Housing and Urban Renewal in Newark, New Jersey," Senior Thesis, Princeton University, April 1970.

[15] The city commissioners' "close relationships" with the NHA apparently included an active role in deciding sites and all other NHA activities. The Essex County prosecutor had planned to bring charges of illegal interference before a grand jury, but suspended his investigation when NHA's executive director departed; see Kaplan, Urban Renewal Politics, pp. 39–40.

The new executive director, Louis Danzig, took over shortly before the passage of the Housing Act of 1949. When NHA was designated as Newark's renewal agency, Danzig and his staff moved quickly to meet what they perceived as the city's major redevelopment problem—the need for middle-income housing. Their early experience in attempting to fulfill this objective was much like that in Trenton. In 1952, having announced the agency's first project, to be located in Newark's North Ward, NHA encountered great difficulty in attracting developers. Active efforts to generate bids finally resulted in a contract in 1957, but the developer then withdrew. Not until 1958 was a firm agreement made with a developer for the site.

The difficulties encountered in this first project led the NHA staff to adopt a different strategy. Unlike the Trenton agency, which selected a massive 100-acre site and became enmeshed in complex political and economic debates on how to proceed, NHA decided to focus on parcels of 10 to 30 acres. NHA also altered its strategies to ensure that projects would in fact be built and that public criticism and debate would be muted. Rather than attempting, within NHA, to decide what specific types of projects—middle-income housing, luxury apartments, light industry, office complexes, etc.—should be located at each site and then seeking a developer, Danzig and his aides now defined their mission more broadly. NHA's goals would be to "tear down substandard housing" and attract capital for new construction, with the expectation that these efforts would serve as "significant steps to reverse Newark's decline." With these revised objectives, authority officials then began negotiations with private developers, and after "long months of pressure" were able to overcome Newark's negative image and persuade developers to undertake projects in the city.[16]

It is important to note that the characteristics of particular projects—housing, office buildings, etc.—were substantially shaped by the developers, within the broad guidelines of federal statutes. But the role of the local NHA staff was also crucial. In contrast with the Trenton authority, Danzig and his aides were able to use political skills to attract wary developers, build an alliance, and insulate that alliance from a range of diverse constituencies, thus permitting them to attract millions of dollars of investment into Newark. In the absence of these activities, the pattern of housing and commercial development would have been far different.[17] In shaping the renewal system, NHA's public entrepreneurs were motivated far less by a desire simply to "support" the private market than by a broader concern with Newark's future as a city—and by the lively and perhaps essential interest in enhancing their own power and reputation.

Once tentative agreement had been reached between these two central actors—NHA and a private developer—Danzig's staff negotiated with the

[16] Ibid., pp. 26, 28.

[17] From the vantage point of 1980, two students of Newark—no friends of NHA—underscore the beneficial impact of urban renewal on the city: "In the absence of the efforts that have gone into development the city would be far worse off than it is. The thousands of units of public housing, the improvement of transportation systems, and the economic growth that development has involved—not to mention the impact of physical construction on employment in the city—all these are and have been important to the city and kept bad from being the worst." Robert Curvin and Duane Lockard, "Newark: Another American Tragedy," typescript, 1980, p. 297.

Urban Renewal Administration and other federal funding sources. The regional URA office was under some pressure to support NHA proposals, since the New York and Philadelphia areas were strewn with vacant sites and incomplete renewal projects during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Even so, on some projects NHA spent several months working out detailed plans to meet the requirements of the private developer, URA, and other federal agencies.

At this stage, an agreed-upon project was taken to City Hall for ratification by the mayor and other officials. Local rejection at this time was "extremely unlikely," as Kaplan points out, since any effort to alter the project would "disrupt the balanced network of negotiations and probably stop the flow of capital into Newark."[18] Often the mayor was given the project plan shortly before a federal deadline for action, increasing the pressure for him to agree. The mayor also was permitted to announce the project, thus taking credit for the benefits expected to flow from the redevelopment activity. And by letting local political leaders get credit for its projects, NHA built support for its future efforts.

As a result of these complex, low-visibility operations, NHA was able to announce two or three new projects every year between 1957 and 1965. Underlying these results was a high level of planning and technical skill within the NHA staff, combined with considerable political sophistication. Equally important was the authority's deference to the basic imperative represented in the federal renewal laws: Urban renewal projects would have to meet the preferred goals of developers, and those goals generally involved central location, an attractive and relatively safe environment, and—crucial for most developers—the likelihood of making substantial profits. Consequently most of NHA's projects involved high-priced apartments or commercial and educational buildings in the downtown area.

The importance of political skill to NHA's activities can be seen most clearly in the way the authority staff dealt with constituencies other than those with which it was closely allied. One of the primary factors in determining whether an organization will be able to achieve its goals is its ability to restrict the intervention of other groups whose interests are affected by its actions. For NHA and other functional authorities, this task is made easier by narrow functional scope and often by access to external sources of funds. Nevertheless, as the Trenton Housing Authority experience shows, the urban renewal process offers considerable opportunities for outside intervention. NHA's staff devoted substantial amounts of energy to neutralizing potential sources of intervention. A large part of Harold Kaplan's book is devoted to describing these efforts, which included five major dimensions:

Neutralizing the NHA commissioners. Before 1948, NHA's commissioners frequently intervened both in project details and in the authority's general policies. During those years, executive directors at times "came to Board meetings without carefully prepared proposals, permitted aimless and chaotic debate among the commissioners, and often proved unable to answer questions" on NHA activities.[19] These conditions ended when Danzig took

[18] Ibid., p. 30.

[19] Ibid., p. 47.

over the authority, just when the agency prepared to expand into urban renewal. Danzig and his aides prepared the agenda, brought project proposals to the board after obtaining commitments from developers and federal agencies, and had a detailed knowledge of all issues that might be brought up at board meetings. Between 1948 and 1962, NHA's commissioners never modified a staff proposal, and its endorsements of the staff's recommendations were usually unanimous.

Offering minor concessions to local political leaders. Soon after he assumed the leadership of NHA, Danzig developed a working arrangement with Newark's elected officials. The city commissioners tacitly agreed not to interfere with general policies such as site selection and naming of redevelopers. In return, NHA's staff gave considerable weight to political sponsorship in making appointments to minor positions, as well as on matters having constituency impacts such as tenant selection and eviction. Many of these latter activities concerned NHA's public housing projects rather than urban renewal. Thus the authority was able to use its resources in one policy area to help maintain general control over another activity that NHA's staff regarded as more essential.[20]

Denying the city planners a role. Under state law, Newark's Central Planning Board (CPB) had important responsibilities in the field of urban renewal, since it was required to determine whether blight existed in a renewal site, and to certify that the redevelopment plan was consistent with the city's master plan.[21] Consequently, the city planners expected to be involved in the early stages of all NHA renewal planning. Danzig and his aides viewed the situation quite differently. Like Robert Moses and many other leaders of functional agencies, NHA's top staff viewed citywide planning as an infeasible, utopian ideal. Moreover, they recognized that to include the CPB as part of the main negotiating alliance would add both to the complexities of the process and to the range of interests that would have to be accommodated. Also, during this period the CPB lacked staff resources and thus could not be expected to add much to the renewal agency's analyses of complex economic or technical issues. Thus the NHA decided to confer with the planners only after a project had been formally announced, a position that was maintained despite occasional CPB grumbling.

Winning the support of other city agencies. As the Trenton Housing Authority learned to its dismay, renewal projects require support from local agencies involved in sewer relocation, street widening, and other public construction activities. NHA used the need for cooperation as an opportunity to

[20] Compare the similar strategy of the Tennessee Valley Authority in electrical power generation and agricultural development; see Philip Selznick, TVA and the Grass Roots (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1949), pp. 57 ff. For a discussion of comparable activities by the Port Authority, see Jameson W. Doig, Metropolitan Transportation Politics and the New York Region (New York: Columbia University Press, 1966), pp. 67 ff.

[21] These powers were conferred on the Central Planning Board by the New Jersey Redevelopment Agencies Act of 1949, which empowered local agencies to take part in the federal renewal program.

strengthen its own position. NHA staff members pointed out to the Department of Public Works and other city agencies that they could expand their own activities if they participated in the growing, federally funded renewal program. The Board of Education was willing to cooperate in projects that included new schools, since part of the capital cost would be paid by the federal government. Such cooperative efforts between the NHA and local agencies made it more difficult for City Hall to control the NHA by direct manipulation of the one-third local share, or by encouraging dissension among the various city bureaucracies. Before the elected officials were brought into project planning, a complex net of mutual financial and psychological obligations had been woven by Danzig and his aides. And these other city agencies, having less concern than NHA with overall planning and development issues, left the formulation of particular projects in the hands of the executive director and his staff.

Muting those to be displaced. Many of NHA's projects required the demolition of residences and small business properties. Recognizing that the people who would be displaced formed an important potential source of opposition, the authority neutralized this threat in several ways. Most important was the strategy of silence—a lack of publicity about new projects until support had been obtained from the Urban Renewal Administration, developers, other city agencies that would be involved, and the elected officials. When a project was announced, NHA was required by the federal government to provide detailed information on relocation requirements, but this information—some of which suggested ways tenants could resist vacating renewal sites—was conveyed in only cursory fashion. Moreover, NHA kept in close contact with leaders of the black community, where most of the displacement occurred, and authority officials were able to convince them that on balance NHA efforts were helpful to their constituency. Vocal critics from the affected neighborhoods sometimes were given NHA jobs and other rewards. Because of these efforts, little effective opposition to authority projects developed during the first 15 years of renewal in Newark. Other constituencies, such as the downtown business community, also were attended to by NHA's politically sensitive leaders without hampering the basic structure of the authority-URA-developer alliance.

Thus its political skill enabled NHA to restrict the variety and intensity of constituency demands. While its counterpart in Trenton—with similar structural characteristics—succumbed to onslaughts from local interests in the early 1960s, the Newark agency kept these pressures at bay. Working in close alliance with private developers and federal funding agencies, NHA steadily expanded its renewal activities. By the end of 1966, the urban renewal alliance had produced 18 projects in Newark—either completed or in process—covering more than 2,400 acres. NHA's program ranked fifth in the country in terms of federal funding, and as the authority exclaimed in a brochure entitled City Alive!: "the strength and vision generated by this alliance of government and business have enabled Newark to undertake more urban renewal, on a per capita basis, than any other major city in the nation."[22]

[22] Newark Housing Authority, City Alive! (Newark: 1966), p. 6.

The Fragile Structure of Newark's Success

"In the world of urban renewal," Harold Kaplan commented when the Newark Housing Authority was riding high in the early 1960s, "project building seems to yield more project building. . . . After a certain point successful agencies can do nothing wrong. They are rarely involved in political skirmishes because they are rarely challenged."[23] In a few short years, however, the world of urban renewal in Newark collapsed. Constituencies that had been quiescent became active and influential. Ghetto blacks, whose previous role in renewal had been only an occasional irritant, became a major force. This challenge to NHA's policies—sparked by an ill-conceived proposal to use a huge tract of land in the ghetto for a state medical college, and dramatized by a devastating riot in 1967—fundamentally altered the politics of redevelopment in Newark. Faced with new and intense pressures, the alliance that had shaped urban renewal shivered and fell apart. Federal and state roles altered sharply; private developers faded in importance; Danzig, the skillful public entrepreneur who had molded and maintained the renewal alliance in Newark, departed. And the most "successful" urban renewal program in the New York region lost much of its capacity to make a significant impact on the pattern of development in Newark.[24]

Underlying these changes was increased dissatisfaction and political activism on the part of Newark's black residents. Rapid escalation of ghetto demands for more relevant programs and a meaningful role in the development process occurred in cities across the nation in the early 1960s. In Newark as elsewhere, blacks began to question programs that provided neither benefits nor a meaningful role for community and minority interests. By the mid-1960s, Newark's urban renewal had cleared nearly 6,000 dwelling units in neighborhoods selected by NHA for redevelopment. Yet 40,000 of the city's 136,000 housing units remained below national standards, giving Newark the highest proportion of substandard housing of any major city in the United States. From the perspective of NHA, "housing conditions in Newark [were] better than they have been in our time."[25] But for ghetto dwellers, housing conditions were "indescribably bad."[26] Moreover, urban renewal reduced the amount of housing available to poor families. A tight housing market, poverty, and racial discrimination compromised the ability of NHA to relocate the uprooted in the "decent, safe, and sanitary" dwellings called for in the Housing Act of 1949. As a result, large numbers of those displaced by redevelopment were resettled in slum housing, where they often paid higher rents and soon were uprooted again by the public bulldozer. To a state investigating

[23] Kaplan, Urban Renewal Politics, p. 35.

[24] The discussion below is based mainly on the following sources: M. Duncan Grant, "Housing Authority Politics in Trenton and Newark"; Robert Curvin, "Black Power and Bureaucratic Change," Graduate Seminar Paper, Princeton University, December 1971; David Marshall, "Urban Renewal in Newark"; New Jersey, Governor's Select Commission on Civil Disorder, Report for Action (Trenton: 1968); and Harris David and J. Michael Callan, "Newark's Public Housing Rent Strike," Clearinghouse Review, 7 (1974), p. 581.

[25] Louis H. Danzig, executive director, Newark Housing Authority, quoted in New Jersey, Governor's Select Commission on Civil Disorder, Report for Action (Trenton: 1968), p. 55.

[26] Committee of Concern, a black civic group, quoted in "Asks Study of Violence," Newark News, July 18, 1967.

commission reporting in 1968, it seemed "paradoxical that so many housing successes could be tallied on paper and on bank ledgers, with so little impact on those the programs were meant to serve."[27]

Significant black opposition to NHA first emerged about 1960, in connection with the authority's effort to renew the Clinton Hill area of the black Central Ward. The Clinton Hill Neighborhood Council fought to protect the interests of the area's black residents. Also during the early 1960s, the Congress of Racial Equality and the Students for a Democratic Society generated protests on housing and other problems, such as job discrimination and police brutality. But these early efforts were sporadic, and made little impact on NHA and its allies. Newark's urban renewal alliance continued its normal pattern of decisionmaking well into the decade, with no significant involvement by the city's growing and increasingly alienated black community.

The Medical College

Business as usual for NHA and its allies led to a spirited effort to persuade the trustees of the New Jersey College of Medicine and Dentistry to locate the state medical school in Newark. From NHA's perspective, the prospect of attracting the $60 million educational facility was another potential milestone in the process of converting "badly used land to higher and better uses," another step in making Newark a "city alive."[28] Danzig, Mayor Hugh Addonizio, and other city officials met privately with the medical school's trustees, while the city's newspapers and downtown business leadership waged an intensive public campaign during 1966 to convince the college that central Newark was a better site than suburban Madison in Morris County, the location preferred by most of the school's officials.

Initially, NHA and the city government offered the medical school a 20-acre site in the Fairmount Urban Renewal Project. The trustees responded by praising Newark as a potential home for the medical school, but insisted that the college needed 150 acres, presumably much more land than could be made available in crowded central Newark. NHA and City Hall were dismayed, but not ready to quit despite the college officials' obvious desire for a suburban location. If the medical school had to have 150 acres, Newark would provide 185 acres in the black Central Ward. A city official later explained the strategy developed by Newark in the fall of 1966:

We thought we would surprise them . . . and we drew a 185-acre area which we considered to be the worst slum area. It included Fairmount and surrounding areas, which was clearly in need of renewal, and we were going to proceed with the renewal in any case in that area. . . . We felt in the end they would come down to 20 or 30 acres in Fairmount, or in a battle we might have to give up some more acreage. We never felt they would ask for 185. We felt it was a ploy on their part.[29]

[27] Governor's Select Commission on Civil Disorder, Report for Action, p. 55.

[28] Newark Housing Authority, City Alive! p. 8.

[29] M. Donald Malafronte, assistant to Mayor Hugh J. Addonizio, quoted in Governor's Select Commission on Civil Disorder, Report for Action, pp. 12–13.

Responding to Newark's bold offer, the medical school continued to demand 150 acres. The trustees then upped the ante by specifying that the college would come to Newark only if NHA and the city government were able within 10 weeks to "complete legal and financial assurances that will provide the college with a site of some 50 acres upon which it would begin initial construction by March 1, 1968 . . . [and] irrevocably commit approximately 100 additional acres for future college use to be promptly cleared and deeded to the college as the need for the land is determined . . . solely by the trustees."[30] To make things even more difficult for the city, the initial fifty acres was not to come from cleared land in the Fairmount urban renewal site. For city officials, the trustees' demand for uncleared land "was a slap in the face. . . . It was our opinion that they were attempting to get out of the situation. . . . What they wanted was across the street from cleared land. This to us was insanity and enraging because they knew this was not an urban renewal area. They knew that the urban renewal process is three years and perhaps five."[31]

Despite the dismay over the trustees' intransigent position, Newark's leaders were determined to secure the prize of the medical college. The medical school's offer was accepted in December, with the mayor expressing confidence that "we can meet all the provisions set by the trustees."[32] To ensure quick assembly of the initial 50-acre parcel, the city was prepared to use its power of condemnation, and NHA was ready to cut back other urban renewal projects to make funds available to underwrite land acquisition for the medical school. Trenton offered a helping hand, as the state legislature with the blessing of Governor Hughes authorized Newark to condemn land for the college, and to extend its debt limit by $15 million to provide the funds for the initial land acquisition. Support also came from NHA's allies in Washington. Officials at the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)agreed to the methods employed by Newark in shortcutting the normal urban renewal procedures for the medical college. They also, in Mayor Addonizio's words, assured "us it will qualify as an urban renewal project."[33]

During the complicated bargaining that brought the medical college to Newark, none of the principals paid much attention to the views of the several thousand black families living in the 150-acre target area. For proponents of the project, replacement of a ramshackle black neighborhood by the medical school meant new vitality for Newark, $15 million in new jobs, and the elimination of a slum that was estimated to cost the city $380,000 more annually in public services than it generated in taxes. But from the perspective of the Central Ward's black dwellers, a medical school "in the heart of the ghetto," like Newark's "vast programs for urban renewal, highways, [and]

[30] Statement of the Board of Trustees of the New Jersey College of Medicine and Dentistry, quoted in Malcolm M. Mamber, "Newark Is Given March I Deadline to Provide Medical Center Land," Newark Sunday News, December 11, 1966.

[31] Malafronte, quoted in Governor's Select Commission on Civil Disorder, Report for Action, pp. 13–14.

[32] Mayor Hugh J. Addonizio, quoted in Bob Shabazian, "City Pledges Land Med School Asked," Newark News, December 23, 1966.

[33] Quoted in "Council Pledges Med School Funds," Newark News, December 27, 1966.

downtown development . . . seemed almost deliberately designed to squeeze out [the] rapidly growing Negro community that represents a majority of the population."[34]

In NHA's vast renewal projects of previous years, grass-roots protest had been haphazard and ineffective. But by 1967, the black population in Newark had grown to a majority, and the increasing political sophistication of black citizens and their organizations made it possible to develop sustained opposition to this latest renewal scheme. Resistance to the medical school plan mounted rapidly in the Central Ward during the spring of 1967. Residents of the target area enlisted the support of many black leaders in organizing the Committee Against Negro Removal, which argued that the medical college's benefits to the city "would be less than the misery it would cost."[35] Newark's antipoverty agency, the United Community Corporation, publicly opposed the project. Underlying black opposition to the medical college was a lack of communication between official Newark and the ghetto, development priorities that largely ignored the poor, and the pervasive fear of relocation. Commenting on the third factor, a state commission later emphasized:

Many residents did not believe official reassurances on this subject. People hear that in the past families have been displaced by urban renewal and forced to live wherever they could, and they see few vacant apartments of decent quality in which they know they can afford to live. The statistics on the quality of vacancies support the view of the people in the area. . . . The Medical College case simply brought these fears to a head.[36]

The rising chorus of black protest made little impression on NHA and City Hall, which focused their energies on the difficult task of meeting the medical college's stipulations. Negotiations between HUD representatives and city officials led to a federal agreement to rush $15 million to Newark to aid the project. Mayor Addonizio and NHA then pressed for City Planning Board approval of the large area as blighted, and the board held blight hearings in May and June. Despite vociferous opposition from blacks at the hearings, NHA was ready to move forward rapidly with clearance.

But NHA's opponents did not fade away as they had in the past. Discontent over the medical college combined with another racial controversy—in school politics, where the appointment of a white official to a top Board of Education post drew vigorous black protests—to make black Newark a tinderbox. The spark was provided by a confrontation between blacks and the police, and a devastating six-day riot erupted in July 1967. When the smoke cleared from the Central Ward, 26 were dead and over $10 million in property had been destroyed. Black dissatisfaction with the medical school project in particular, and the city's renewal process in general, had been tragically underscored.[37] Business as usual was over for the Newark Housing Authority.

[34] Tom Hayden, Rebellion in Newark (New York: Vintage, 1967), p. 6.

[35] See Douglas Eldridge, "Displacees Fight Med School Site," Newark News, January 11, 1967.

[36] Governor's Select Commission on Civil Disorders, Report for Action, pp. 61–62.

[37] The riot and its causes are summarized in Report for Action, especially Chapter One. On the evaluation of protests against the medical school project, see Grant, pp. 126–131.

The Collapse of the Urban Renewal Alliance

Of the Newark riot's many lessons, one of the clearest was the hostility of the city's black population to urban renewal and the kind of "successes" produced by NHA and its allies. With their opposition to the medical school and NHA's approach traumatically dramatized, black interests were able to enlist new allies in their opposition to the renewal alliance, and to exercise increasing influence within the city. The state government abandoned its passive role, and became an active participant in the effort to redesign the medical school project. Federal policy also changed, placing more emphasis on relocation needs and on community involvement in the renewal process. Within three years of the riot, the growing numbers of blacks and increased political sophistication resulted in the election of a black mayor in Newark. These and related changes eroded the independent power of the Newark Housing Authority, and thus destroyed the basis for the alliance which NHA had so skillfully constructed in the 1950s.

Traditionally, state officials in Trenton had deferred to the federal/local alliance in determining the direction of renewal programs, becoming active only to facilitate agreements already made by the alliance when legislation or other state concurrence was required. As noted above, this approach had been followed on the medical school, as Governor Hughes signed legislation in March permitting Newark to condemn, buy, and sell the land needed for the 150 acres demanded by the trustees. Two weeks after the riot, however, the state administration began to reverse its course. Hughes and his aides pressed the medical school to reduce the campus to 50 acres. They sought to convince the city to use the remaining land for low-income housing, child care, health centers, and other community projects. State officials also urged the city to ensure that representatives of the renewal area take part in planning for the projects. Little support for the state's proposal came from NHA and City Hall, which were fearful of losing the medical school, and of sharing their power over redevelopment decisions with the rebellious ghetto. Equally unresponsire was the medical college, whose president continued to insist that "we have a contract for 150 acres," and whose trustees responded to pressure by threatening to seek a site outside Newark in the suburbs.[38]

The resistance of NHA and elected Newark officials to the state initiatives ensured that state officials would become central participants in working out a compromise between the city, the medical school, and the host of local interests now seeking a piece of the action. At this juncture the state's efforts received a powerful assist from Washington, for HUD would not approve the use of urban renewal funds to clear the site in the face of strong community protests, and in the absence of an acceptable relocation plan. Responding to these pressures, the city and the medical school reduced the campus to 98.2 acres, and shifted the site slightly to reduce the number of families to be relocated.

These proposals, however, did not satisfy black demands on relocation and participation. At this point, Washington sided with the neighborhood forces. Early in 1968, HUD and the Department of Health, Education and Wel-

[38] Dr. Robert A. Cadmus, quoted in Ladley K. Pierson, "Med School Debate Seen 'Historic,'" Newark News, March 3, 1968.

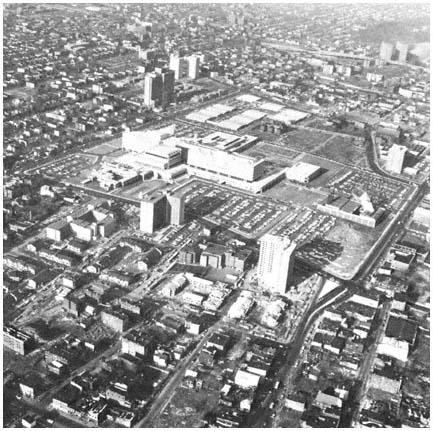

The completed campus of the New Jersey College

of Medicine and Dentistry. Even though the plans

for the campus were scaled down after

the Newark riot, a large amount of land still was cleared for

the project, displacing low-income blacks from housing

similar to that surrounding the campus.

Credit: New Jersey Housing Finance Agency

fare—which provided much of the funding for construction of the medical college—indicated that the $43-million in urban renewal and medical facility grants would be approved only if there were agreement with the community on seven issues: (1) the amount of land to be used by the college; (2) community health services to be provided by the medical school; (3) relocation of residents from the campus site; (4) employment practices during construction of the school; (5) employment and training policies of the college; (6) future housing programs in Newark; and (7) community participation in the federal Model Cities program, which was just getting underway in Newark.

In the face of these federal, state, and community pressures, Newark officials and the medical college had no alternative but to compromise. The college agreed to limit its campus to 57.9 acres, and to provide a wide range of community and medical training services. City Hall and NHA agreed that

neighborhood representatives would have a veto over development programs in the area surrounding the college, as well as a role in planning the construction of new housing in the city. In addition, the state promised to provide rent supplements where necessary for the 580 families on the site, each of whom was guaranteed relocation.[39]

NHA emerged from these negotiations a much weaker organization. In the future, it would have to share important powers with neighborhood interests, most of whom were hostile to the agency. Equally important, NHA could no longer count on the support of federal renewal officials. As we have seen, NHA's central role in urban renewal was closely linked to the financial support and program concurrence of the agency's federal allies. Before the riot, HUD had rushed to provide $15 million in support of the medical school project. Now, HUD was dealing directly with representatives of Newark's black and Puerto Rican communities, supporting their demands for improved relocation practices, and insisting that these groups be represented in NHA decision making. Moreover, as the complex negotiations over the medical college evolved after the riot, the role of state and community representatives became increasingly important, and NHA faded into a relatively minor role. The traditional pattern of NHA leadership was broken.

Not long after the medical school negotiations were completed, Louis Danzig resigned as NHA executive director. Danzig cited reasons of health, but he obviously was dissatisfied with the restricted role of his Authority in the medical college project and other programs in the post-riot era. In any event, the most important individual in making the renewal alliance work was gone. Moreover, his successor, promoted from within the agency, lacked the basic ability and political skills of a Louis Danzig.

At the same time that NHA was losing its control over the renewal process, the agency came under attack from the residents of its housing projects. NHA's tenants traditionally had been submissive, and had acquiesced in the authority's strategy of creating and controlling "tenant" groups. But the rising political consciousness of Newark's poor blacks and Hispanics, combined with their success in the medical school negotiations, led to increased militancy among residents of NHA's massive public housing projects. Independent tenants' associations were organized in 1968 and the following year a rent strike was initiated in protest against inadequate NHA facilities, repair programs, and safety measures. A second rent strike began in 1970 and continued for more than four years. The second strike had a particularly devastating effect on NHA's financial position, as several million dollars in rent payments were withheld from the agency during these years.

As the second rent strike began, NHA's ally in City Hall, Mayor Hugh Addonizio, was challenged at the polls by a black candidate, Kenneth A. Gibson, who was supported by a broad coalition of community and minority interests. One of Gibson's major campaign themes was to attack NHA's renewal policies and housing management programs. Gibson also endorsed the rent

[39] The state also pledged that at least one-third of the journeymen and one-half of the apprentices employed in the construction of the college would be black or Puerto Rican. For the details of the final agreement, see Paul N. Ylvisaker, "What Are the Problems of Health Care Delivery in Newark?," in John Norman, ed., Medicine in the Ghetto (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1972), pp. 108–116.

strike. His election in June 1970 as Newark's first black mayor severed another tie that had supported NHA policies and independence. City Hall now joined the federal government, state officials, and community groups in insisting that NHA pursue different objectives and be more responsive to lower-income needs.

Another blow fell on NHA from the agency's one-time allies in HUD. Increasing concern on the part of federal officials about the administrative and financial capacity of the authority led to an investigation of NHA by HUD in early 1971. The resulting report criticized management inefficiency in the authority and urged that NHA be split into two separate agencies, one for public housing management and the other for urban renewal programs. The authority resisted dismemberment, and HUD retaliated by threatening to cut off all federal funds unless NHA complied.[40] This impasse gave Mayor Gibson an opportunity to act as mediator. He persuaded HUD to provide emergency funds to meet utility bills and other immediate costs, and to drop its demand for complete separation of housing and renewal functions. In return, NHA consented to accept a "consultant" designated by Gibson, providing the mayor a means to exercise considerable influence over the authority's decision making. Thus, power over NHA actions shifted toward the mayor's of-rice, although conflict between Gibson and the city council prevented the mayor from exerting commanding influence over the authority.[41] Meanwhile, the rent strike continued until 1974, and NHA limped along, little more than a pale shadow of its former position as one of the nation's preeminent renewal authorities.

In the years since 1974, the mayor's office has used its appointing power, federal guidelines, and its negotiating skills to increase its control over NHA activities, turning the authority into an arm of City Hall's development efforts. Those efforts, which have included several housing, commercial and industrial projects, have had a modest impact on economic vitality and housing quality in Newark.[42] But the evidence bearing on the central theme of this discussion—the impact and strategies of a functionally autonomous development agency—ends with the NHA's collapse in the early 1970s.

The NHA's Urban Renewal Program in Retrospect

At each point in the series of events that reduced NHA's capacity to influence development, one might ask, would the urban renewal alliance have survived had this or that factor not been present? For example, would Newark's development still be shaped by a vigorous, relatively independent renewal alliance if there had been no medical school project? Or if there had been no major riot in 1967? Perhaps, but in view of the broader demographic and political changes in Newark during the 1960s, the nature of that alliance

[40] See U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, (Newark Area Office), "Comprehensive Consolidated Management Review Report of the Newark Housing Authority" (Newark: January 1971).

[41] During 1971–1973, the city council turned down three of Gibson's five nominees to the NHA, and as Gibson's first term drew to a close at the end of 1973, only three of the six NHA commissioners were Gibson appointees.

[42] See Newark Redevelopment and Housing Authority, 1977 Annual Report (Newark: 1978) and Greater Newark Chamber of Commerce, The Newark Experience, 1967–1977 (Newark: 1978).

probably would have been significantly changed, and the pace of renewal greatly slowed. Similar forces were at work elsewhere in the region's older cities, with similar overall impact on urban development, as illustrated in the discussion of New York City in the next section.

The rise and fall of the Newark Housing Authority underscores some general points that are important to an understanding of the variables that determine whether a governmental agency will be able to concentrate resources over time to influence urban development. NHA's experience emphasizes the crucial role an organization's leaders can play in determining the impact of constituency factors and the availability of funds. Robert Dahl's comments on urban renewal in New Haven apply to Newark as well. "Changes in the physical organization of the city," he notes, "entail changes in social, economic, and political organization." To develop a coalition that can continue to operate effectively amid such changes demands unusual leadership abilities. A strategic plan must be "discovered, formulated, presented, and constantly reinterpreted and reinforced." The skills required to identify the grounds on which coalitions can be formed, the "assiduous and unending dedication to the task of maintaining alliances over long periods, the unremitting search for measures that will unify rather than disrupt the alliance: these are the tasks and skills of politicians."[43] In Newark's successful urban renewal program, these political dimensions were located in the authority's headquarters rather than at City Hall. Because of these skills, the alliance grew and prospered, federal funds flowed in, and Newark like New Haven won a national reputation for urban renewal productivity.

As necessary as it is to construct a supporting coalition, the strategies used to neutralize potential opposition are equally crucial. The events recounted above illustrate the importance of these strategies. They also suggest the impact of constituency changes, which can generate serious resistance and undermine an apparently firm alliance. Opposition stemming from alterations in constituency factors may affect an agency or an alliance only in minor ways, or more centrally. An area of agency policy may be attacked, to be followed by remedial efforts that reaffirm or even strengthen the organization and its ability to achieve its goals. But other attacks from aroused constituencies can go to the "heartland" of an institution, fundamentally altering its direction and effectiveness, and perhaps impairing its ability to function at all. The Newark Housing Authority is a "heartland" case as far as its urban renewal program is concerned.

The NHA case in particular illustrates the potential importance of new constituencies that arise and become politically relevant to an agency. The ability of these groups to exert political influence may depend not only on increased numbers, wealth, and other "internal" resources, but also on dramatic incidents —or more precisely on a group's ability to link its concerns with such dramatic incidents which can generate support among other constituencies that are already influential in the policy arena. The leaders of successful functional agencies and alliances are often vulnerable to such strategies, being more likely than most political leaders to develop a "trained

[43] Robert A. Dahl, Who Governs? Democracy and Power in an American City (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1961), pp. 201–202.

incapacity" to perceive and respond to these new constituencies. Compared with leaders of less "successful" agencies and with elected officials, their ability to scan the political horizon for new threats and challenges becomes attenuated. They come to believe, with Kaplan, that "after a certain point successful agencies can do nothing wrong." This was the fatal weakness of Danzig and his allies in the late 1960s, just as it was a limitation of Robert Moses in his slum clearance activities in New York City a decade earlier, and of the leaders of the Port Authority in the early 1970s. Thus, we see that "some princes flourish one day and come to grief the next"; for such a leader, "having always prospered by proceeding one way, . . . cannot persuade himself to change."[44]

Enlarging the Renewal Arena

Mobilization of new constituency interests also brought fundamental changes to urban renewal in New York City during the 1960s. New York's urban renewal program was initially directed by Robert Moses, who brought his distinctive entrepreneurial style to the city's Slum Clearance Committee. As indicated earlier, Moses undertook a vast renewal program, clearing hundreds of acres for the construction of luxury apartments and a variety of educational, cultural, and health facilities. Particularly devastating for the poor were the relocation practices of the Slum Clearance Committee. Responsibility for relocation was turned over to the private sponsor, along with title to the property to be redeveloped. In one project:

82 percent of the tenants received neither moving nor rehousing assistance or payments. Many residents had been handed eviction notices without court orders. Others were merely "relocated" to remaining buildings on the site (thus continuing the sponsor's income), although the buildings had no heat, hot water, or basic maintenance, and in spite of the fact that such rerenting was against City laws.[45]

Moses' relocation practices, along with urban redevelopment's conspicuous failure to improve housing conditions for the poor, produced increasingly vocal demands for fundamental changes in New York City's renewal program. Of the many battles fought in the city, perhaps the most significant was the prolonged struggle on Manhattan's West Side between representatives of the poor and New York's urban renewal alliance.[46] Conceived in the mid-1950s, urban renewal on the West Side was designed to restore a rapidly deteriorating neighborhood to its former role as a bastion of the upper middle class. The city's original plan for the West Side Urban Renewal Area called for 5,000

[44] Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince, translated by George Bull (Baltimore: Penguin, 1961), Chapter 25.

[45] Jeanne R. Lowe, Cities in a Race with Time (New York: Random House, 1967), p. 83. Moses's urban renewal activities also are discussed in Robert A. Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (New York: Knopf, 1974), pp. 703 ff.

[46] For a detailed discussion of urban renewal on the West Side, and particularly the role of neighborhood groups, see J. Clarence Davies, Neighborhood Groups and Urban Renewal (New York: Columbia University Press, 1966), pp. 110 ff.

luxury apartments and 2,400 middle-income units. For the West Side's poor, urban renewal planners offered a pittance—only 400 of the 7,800 apartments would be low-income public housing. To clear land for the project, 6,000 families would have to be relocated. Most of these were Puerto Ricans and blacks, and many had previously been displaced by Moses's upper-income Manhattantown renewal project to the north, and his largely nonresidential Coliseum and Lincoln Center projects to the south.

Announcement of these plans provoked immediate neighborhood demands for more low- and middle-income housing. In response, urban renewal officials changed the housing mix from 5,000-2,400-400 to 3,600-3,600-600. Opponents rejected these modifications, which increased the low-income share by only 200 units, as inadequate in the light of the area's housing needs and the dislocations that urban renewal would cause. To press their case more effectively with the city, local resources were mobilized through the organization of the Strycker's Bay Neighborhood Council, a coalition of block associations, ethnic groupings, parent-teacher organizations, and political clubs. As Davies points out, the campaign was facilitated by the presence of middle-class residents, who supported a wide range of community organizations. Foremost among these were the liberal, issue-oriented, reform Democratic clubs that dominated political life on the West Side during the second decade after World War II. Most of the poor in the target area were Puerto Ricans, and their influence in negotiations with the city was enhanced by the assistance of representatives from the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, whose officials commanded more attention at City Hall than did local Puerto Rican leaders. After three years of intensive political activity, the West Side coalition won substantial compromises from the city, with the final plan calling for 2,000 luxury apartments, 4,900 middle-income dwellings, and 2,500 units of public housing, a more than sixfold increase in the number of low-income homes over the city's original proposal.

Virtually every renewal project developed in the region's older cities in the 1960s reflected the increased political influence of the poor, and the greater willingness of renewal agencies to respond to minority and low-income city dwellers. Other grass-roots interests also were listened to, making urban renewal no more easy to undertake in working-class ethnic neighborhoods than in impoverished black or Hispanic communities. Greater involvement of the heterogeneous constituencies of the older cities has had a predictable impact on the ability of urban renewal agencies to concentrate resources on development goals, as Jeanne Lowe points out in an analysis of renewal in the 1960s:

The more the city tried to please the people, the slower execution of the program became, and the more government subsidy was required. In fact, so much time was spent listening to the people and trying to make plans acceptable to diverse community and citywide groups that it was hard to advance projects. The city agency had to deal not only with the officially recognized local renewal councils; self-appointed spokesmen for various communities and independent citizens committees also would spring up in project areas. Often the latter developed plans which, they maintained, more truly represented what the community

desired, and the newspapers were quick to pick up the protests of any articulate critic.[47]

Moreover, citizen groups urged that housing programs be used to advance a great variety of social goals, including "balanced neighborhoods, community preservation, integration or deghettoization." As Lowe comments, few city officials or community advocates were willing to admit, however, that "these goals could not coexist within one project area, or perhaps were impossible to realize," given financial constraints and sharp divisions in priorities and attitudes within local communities.[48]

Many of these problems were illustrated by the efforts of the Lindsay administration to focus redevelopment resources in the poorest areas of New York City, and to involve residents of target areas in the planning and development of renewal projects. Awaiting John Lindsay when he took office in January 1966 was a $3.25 million planning commission study of housing and renewal which urged City Hall to concentrate its renewal activities where they were needed most, "in the Harlems and Bedford-Stuyvesants of the city."[49] Immediately after the report's release, HUD indicated that all future renewal projects in New York City would be evaluated in terms of the ghetto priorities established by the planning commission. Within six months, the Lindsay administration had moved to concentrate its urban renewal resources in Harlem, Central Brooklyn, and the South Bronx. One of the first neighborhoods chosen for renewal was Fulton Park in Bedford-Stuyvesant, a black community where 60 percent of the housing units were unsound. Another new target area was a section of Central Harlem with residential densities in excess of 150,000 people per square mile. The last of the three neighborhoods chosen was Bronxchester, a blighted industrial area lacking a single adequate home among more than 900 dwelling units.

Lindsay's renewal priorities were strongly endorsed in a 1966 report prepared for the mayor by Edward J. Logue, who had directed large redevelopment programs in New Haven and Boston, and who soon would become director of New York State's Urban Development Corporation. To bring renewal closer to the people, Logue urged the creation of area administrators to direct redevelopment within the target areas. Area administrators were named in 1967 as part of the reorganization of the city's housing agencies into the Housing and Development Administration. The new Housing and Development Administrator called "decentralization . . . essential to the effectiveness of urban renewal,"[50] while his deputy believed that the poor should control the redevelopment of their communities.[51]

Despite these changes and the commitment of top officials, renewal strategies focused on the needs of the poor proved extremely difficult to

[47] Lowe, Cities in a Race with Time, pp. 104–105.

[48] Ibid., p. 105.

[49] New York City, City Planning Commission, Community Renewal Program, New York City's Renewal Strategy/1965 (New York: 1965), p. 44.

[50] Jason R. Nathan, quoted in Steven V. Roberts, "City to Decentralize the Administration of Urban Renewal," New York Times, January 16, 1967.

[51] The official was Eugene S. Callender, who headed the New York Urban League before joining the Lindsay Administration; see Steven V. Roberts, "Top Role for Poor in Housing Urged," New York Times, December 17, 1967.

implement. A basic problem was the nature of urban renewal. The federal program, with its heavy dependence on the private developer, was not designed with the poor in mind, a reality that no amount of rhetoric by local or federal officials could alter. Without substantial public subsidies beyond those involved in the acquisition and improvement of land for redevelopment, the economics of urban renewal's public-private partnership were not easily met. Moreover, private developers were wary of investing in an urban renewal project that included substantial amounts of low-income housing. In the West Side renewal area, only 1,500 of the negotiated 2,500 low-income units were built, largely because developers persuaded city officials that too much public housing would jeopardize the market for the project's luxury and middle-income apartments.

Involving a wide range of interests in renewal—particularly in poorer areas where a variety of new groups and leaders jockeyed for influence—inevitably delayed the development and implementation of projects. Community participation is a confusing and time-consuming process. "A community always comes up with 60 different ideas," a New York official points out; "there is never any unanimity."[52] Complicating the process further was the emergence in the late 1960s of a group of community participants skilled in the politics of development, many of whom were employed in antipoverty, Model Cities, and other inner-city programs. To satisfy these varied constituencies, renewal agencies tended to propose more projects than they could handle, to promise more than they could deliver, and to find themselves enmeshed in ever more complex funding, policy making, and administrative arrangements. Perhaps a bit wistfully, New York's top housing and renewal official told a reporter in 1969 that there was no turning back the clock to the less complex and more productive arrangements of urban renewal's early years: "You can't do it any other way today. The old Moses approach of condemning 700,000 units of housing and expecting everybody to sit still—those glorious unsophisticated days are gone."[53]

The Lesson of Urban Renewal

Urban renewal provided the region's older cities with a potential means of concentrating resources on development objectives. Federal renewal funds increased the resources available to the city for shaping the pattern of development. But the Housing Act of 1949 predicated renewal on the involvement of private developers, which meant that local renewal objectives had to be congruent with those of developers. Within this context, skillful leaders such as Danzig in Newark or Moses in New York could concentrate substantial resources on whatever objectives were shared by the renewal agency and developers. The result was a set of activities in some of the region's cities that indeed did shape development—by improving downtown areas, increasing

[52] Eugene S. Callender, deputy administrator, Housing and Redevelopment Administration, quoted in Roberts, "Top Role for Poor in Housing Urged."

[53] Jason R. Nathan, Housing and Development Administrator, quoted in David K. Shipler, "Urban Renewal Giving the Poor Opportunity to Increase Power," New York Times, November 9, 1969.

the supply of upper-income housing, and adding important cultural and educational facilities.