I, and those who are with me, call you The Word of God

Recall that The Word of God originated in 1967 when Steven Clark and Ralph Martin, who had begun their partnership at Notre Dame University through activity in the Cursillo movement and who had undergone the Pentecostal Baptism in the Holy Spirit during a weekend retreat with the original Catholic group from Duquesne University, were invited to work at the student parish of the University of Michigan. With two comrades they held their first prayer meetings in a rented apartment, a site that remains a landmark on a Charismatic tour of Ann Arbor. Within a year they had recruited additional members from the local university and from Notre Dame and as was typical for rapidly expanding prayer groups at the time, added a second smaller weekly meeting for the core group. As in most Charistmatic prayer groups, core group participants defined themselves as those who were more committed and who wanted to maintain a setting of spontaneity and intimacy free from the need to "serve" or integrate newcomers. A formal initiation process originated when one bedroom was set aside for an explanation session and another for laying on hands in prayer for Baptism in the Holy Spirit. By 1969 the initiation was formulated by Martin into the Life in the Spirit Seminars, which incorporated the basic Pentecostal religious experience, teaching about Christian life, and integration into the group.

The idea of a covenant that would bind members together was put forward in a community conference that year. The conference also established a council of twenty, centered around the community's founders, with vaguely defined leadership responsibilities. A dimension was added to the group's ritual life with the visit of Don Basham and Derek Prince, leaders of the nondenominational neo-Pentecostal Christian Growth Ministries of Fort Lauderdale. They instructed the community on the disruptive effects of evil spirits on interpersonal relationships and on "God's work" and taught the practice of deliverance from evil spirits. During a prayer session that became known as Deliverance Monday the two preachers cast out demons, which exited their hosts in a paroxysm of screaming, crying, and coughing. The reported effect for those who were not frightened away was freedom from "relationship problems" and a "bottled up" feeling, in a situation in which the inten-

sity of interpersonal relationships was already having a transformative effect on participants' mode of dealing with the world and each other. Other early covenant communities were also discovering deliverance at this time, and it frequently became a required experience for people entering community life.

At a second community conference in 1970, the name "The Word of God" was formally adopted, based on prophetic messages uttered by group leaders. In addition, the leaders put forward a conception of covenant as a formal written commitment among members. Understood to be desired and sanctioned by the deity, it would be publicly accepted by each member in a solemn ceremony. The covenant has four elements: all must attend community assemblies, all must contribute some service to the welfare of community members, all must respect the community order (i.e., the accepted way of doing things and the accepted pattern of authority), and all must support the community financially by tithe. At the conference Clark and Martin outlined their plan for restructuring the group to facilitate community growth. The Life in the Spirit Seminar was subsequently revised to emphasize community living, and members were required to take or retake an additional twelve-week Foundations in Christian Living course. Prospective members could make a preliminary or underway commitment, but only after completing all the courses and being invited by community leaders could they make a "full commitment" to the covenant. "Growth groups," small-scale spiritual development groups that were characteristic of Charismatic prayer groups from the movement's beginning, were reorganized on geographic lines within subcommunities.

The functions of community leaders were categorized by specialty, including charismatic gifts such as prophecy, services in support of the community, and offices such as elder. Those specializing in service received the title "Servant" if male or "Handmaid" if female. The former were charged largely with administrative responsibilities, while the latter's functions included limited pastoral responsibility for other women. Invoking biblical justification for a principle of "male headship," women were excluded from the position of community elder. To eliminate the possibility that outsiders would interpret their actions as aimed at starting a new church, Clark proposed the term "coordinators" instead of elders for those male leaders who, with increased authority under the covenant, would replace the loosely structured council. Martin and Clark became overall coordinators with authority over the others. The local bishop received a proposal outlining this "pastoral experiment."

The authority of the coordinators was consolidated during 1971–1972, as was the structure of the community and its self-conception as a "people." A series of "teachings" on the theme of "repentance" sobered members' attitudes toward their collective project. The coordinators' decision that it was within their power to expel a woman accused of "false prophecy and unrepentant homosexuality" highlighted both their increasing authority and the existence of boundaries between the community and the outside world. The generality of the covenant allowed coordinators gradually to appropriate authority over more aspects of members' lives, and they regarded it as part of their divine mission under the covenant to do so. A decision-making process emerged based on consensus among coordinators as to "what the Lord was telling them" through discussion, prayer, and prophecy, with the ultimate authority residing in Steven Clark.

Input from the community at large was formalized via "community consultations." These were called for by the coordinators when major changes were under consideration, such as adoption of the covenant or formation of the Sword of the Spirit. Five such consultations were held between 1968 and 1990. Each Iasted for several weeks or months, during which members "prayed about" the matter and communicated insights, opinions, or prophecies to the coordinators. In less focused periods, the coordinators expected a general flow of "prophecy mail" from members. The content of prophecy mail was understood as the outcome of members' personal efforts to "listen to the Lord" and receive prophetic inspiration that would propose, comment on, or confirm ideas and trends in group life. Along with these changes, a strict notion of "community order" evolved. This order was exercised in 1975 when a man was excluded from the community after taking his complaints about the hierarchical/authoritarian (and decreasingly "spontaneous") direction of group development directly to the local bishop, rather than through "proper channels," namely, the coordinators themselves.

The consolidation of coordinators' authority in 1971–1972 placed them at the apex of four distinguishable hierarchical systems, based on living situation, personal headship, prophecy, and community service.

The cornerstone of the living situation hierarchy was the "household," organized on a model adopted from the Episcopalian Charismatic Church of the Redeemer in Houston. The household ideally consisted of one or more married couples, their children, and one or more unmarried people. The primacy of intimacy as a goal is evident in the possibility for individuals who did not share a common domicile still to be members of a

"nonresidential household." Following the principle of male headship, the eldest married man was pastoral head of his household. As the community grew into as many as fourteen geographic "districts," each household head was made subordinate to one of several "district heads," who were in turn responsible to a "district coordinator." In 1972, a year after the institution of households, coordinators assumed authority for assigning people to households. In 1976 three higher-level "head coordinators" were ceremonially consecrated to oversee communitywide affairs, with Steven Clark remaining as overall head coordinator, a structure that with minor variations remained in effect until 1990.

The "personal head" is similar to a spiritual adviser, except that he is not necessarily ordained and that "full headship" (required of those publicly committed to the community covenant) entails obedience to the head in matters related to morality, spirituality, and community order.[3] Although formally distinct from the headship of living situations, the same persons often function as heads in a variety of contexts. Furthermore, a household head was often the personal head of most members of that household, and a husband was always personal head of his wife. The coordinators' heads were the head coordinators, who in turn were each other's heads in a fight circular relationship.

In a culture that emphasizes the value of individual autonomy, headship was perhaps the most controversial of covenant community practices, from the perspective of both outsiders and other Charismatics. At the same time, the cultural logic in defense of headship was implicitly framed in terms of the psychocultural themes I have identified as central to Charismatic self process. With respect to control, members were quick to argue that only the most advanced and committed were "under obedience" to their heads. For average members, it was said that heads typically gave advice rather than orders, although given the divinely sanctioned nature of the relationship, such advice had an implicitly coercive overtone. This potential for coercion was dealt with not only by invoking benevolence and attributing divine guidance to the head but especially by appealing to the theme of intimacy. People would describe their relationship as one of deep "sharing" and say "My head really knows me." Finally, the theme of spontaneity was relevant in that although most members typically met with their heads by appointment, there was a sense that they were always available when needed.

Prophecy was originally uttered within and outside of prayer meetings by anyone who felt inspired, but in 1971 a "word gifts group" composed of those recognized for exercising this charism began to meet

regularly. As the community grew in size, public prophecy began to be restricted to members of this group, and a hierarchy of prophets emerged, including both men and women. In 1975 the office of prophet was created within the community and one of the head coordinators, Bruce Yocum, was consecrated as its holder. Under his direction, members of the word gifts group cultivated their capacity to listen to the Lord and took responsibility for distilling and screening the divine word as it came to the coordinators from the collectivity in the form of prophecy mail. In addition, prophecy at community gatherings came to be dominated by this group, and regular members wishing to prophesy would have to clear their message before uttering it to the assembly. This development shows clear compromise between themes of control and spontaneity: although universal access to spontaneous divine inspiration was preserved in prophecy mail and in public gatherings (as well as in smaller service groups, families, and interpersonal relationships), it was subject to control by being filtered through the word gifts group and the community prophet.

While all Charismatic prayer groups have a variety of "ministries" in which members can participate, the requirement of covenanted members to contribute some service to community life led to development of multiple "services." By 1972 an anthropology dissertation on the community recorded forty-four formal services such as evangelization, child care, music, pastoral leadership, healing, initiations, guest reception, or "works of mercy" (Keane 1974: 98–99). These services generated their own hierarchy of headship, again with its apex among the community coordinators.

In 1972 the conservative Belgian Cardinal Suenens paid an incognito visit to The Word of God, subsequently announcing his endorsement of the group and encouraging its members to expand the international horizons of their work. The other principal development in 1972 was the founding of a "brotherhood" of men under Clark and Yocum. These men dedicated themselves to greater discipline and asceticism in service to the community. Living communally in the state of "single for the Lord," or celibate bachelorhood, they became the shock troops of the international expansion encouraged by Suenens. Christened the Servants of the Word, the brotherhood held a ceremonial public commitment for its members in 1974. A "sisterhood" of women living single for the Lord called the Servants of God's Love was not established until 1976, and remains less developed than the parallel brotherhood.

In 1974 a series of teachings by the coordinators reemphasized the

principle of male headship in outlining acceptable gender roles. The office of handmaid was discontinued, perhaps because its holders expected more pastoral responsibility than the coordinators were prepared to grant. The office of handmaid was reinstituted only some years later, after the community's conservative and male-dominated definition of gender roles was firmly entrenched. Also in 1974, the ritual practice of "loud praise" was borrowed from the covenant community in Dallas, transforming collective prayer of praise to the deity from quiet speaking or singing in tongues to loud vocalization and hand clapping. A second visit by the ministers who had in 1969 introduced the practice of deliverance from evil spirits prepared community members to be transformed by divine power through prayer and revelation.

Events accelerated dramatically in 1975. A more apocalyptic tone characterized prophecies and coordinators' teachings. The coordinators decided that the community must become reoriented to a worldwide sense of mission. To emphasize the importance of this mission, each publicly committed member was required to retake the advanced initiation seminars and make a formal recommitment to the covenant. Adapting a practice that Martin had observed in a French covenant community, at the recommitment ceremony each male member was vested with a mantle of white Irish linen, and each female with a veil of white Belgian linen (see photo insert following this chapter). These were to be worn at community gatherings as a symbol that members belonged to a "people" with a divine commission. Internal resistance to adoption of ritual clothing, to the increased demand for commitment of time and finances, and to the additional increase in coordinators' authority led to the first major crisis in the community. For the first time, there was a substantial loss of members—or "pruning" in the biblical metaphor of the faithful—as some declined to make the recommitment and others were excluded from it by the coordinators. Extracommunity developments were highlighted by three events: the annual community conference, which was held jointly with the People of Praise in anticipation of a coming merger; the establishment of the movement's International Communication Office by Ralph Martin and Cardinal Suenens in Brussels; and the utterance of the Rome prophecies at the movement's international conference.

In 1976 the two goals of establishing an Association of Communities and establishing an international evangelistic "outreach" based in Belgium were finally realized. Community coordinators promulgated a series of teachings on "getting free from the world." Community ritual

life was augmented by household "Sabbath ceremonies" adapted from the Jewish seder by a born-again Jewish member. Teachings the following year elaborated community standards of "honor and respect" for one another, between people of different ages and genders, for coordinators and others in positions of authority, and for God. Solemn respect for God was emphasized in ritual life by the new practice of prostration, lying prone or kneeling with one's face to the floor in deeply silent prayer that came to alternate with periods of loud praise. Honor and respect for others was ritualized by the adoption of foot washing, and children began to be taught not to address adults by their first names.

The trend toward world renunciation gained momentum when the public prayer meeting, a feature of the group's ritual throughout its ten-year career, was restricted to members and their guests or prospective members and rechristened a general community gathering. Members were to further simplify their lifestyles, use less meat in their diets, and contribute more to the financial support of the community's mission. In 1979 the community instituted four denominational "fellowships," each with its own chaplain to provide liturgy and church services for members from the Catholic, Free Church, Reformed, and Lutheran traditions. A majority of members, representing approximately twenty denominations, withdrew from local congregations into the community fellowships. This move caused some controversy in the broader Ann Arbor Christian community, given that they took both their volunteer energies and the half of their tithe that they had been contributing to their churches. Also in 1979, a rural district of the community was established on a 260-acre farm purchased by The Word of God.

In spite of the latter development, the community's distinctive style of world renunciation has consistently entailed economic self-sufficiency and sharing of personal resources, rather than withdrawal to rural poverty. Members who own businesses such as a computer firm and a grocery store often employ other members. Members recognize that skilled and white-collar work outside the community both strengthen its financial position and provide opportunities for recruitment. The world renunciation that characterizes this "college-educated community of yuppies," as one of its officials described it, is of a kind that is financially sound.

Yet world renunciation it is. This was nowhere more evident than in the efforts by coordinators to endow their people with a distinct and disciplined culture adequate to the community's perceived mission, by instituting an intensive series of teachings in 1980–1981. Known as

the Training Course, the teachings were based on a massive tome by Steven Clark entitled Man and Woman in Christ (1980). Clark's course made minutely explicit prescriptions for proper comportment, gender-appropriate dress, child-rearing practices, and the domestic division of labor. In addition, it identified global trends presumed to threaten the community mission of building the Kingdom of God—Islam, communism, feminism, and gay rights. With knowledge of its contents withheld from the majority of publicly committed members, the Training Course was initially given only to coordinators and district heads and their families. This strategy for the first time created explicit recognition of the existence of a true elite within the community—and stirrings of apprehension about the coordinators' motives for secrecy. The greatest immediate repercussion of the new formulations was not discontent within the community, however, but the already described split from the People of Praise and the breakup of the Association of Communities, whose members were unwilling to follow the "vision" and "mission" of The Word of God.

Retreat from the "ways of the world" continued in 1982 with the founding of a community school encompassing grades 4 through 9, judged to be the most formative years for community children's morality and spirituality. Partly because many families now had young children, multiple-resident households became less pragmatic and began to be replaced by nuclear family dwellings organized into "household clusters." Meanwhile, The Word of God's distinct vision was promulgated to the broader Catholic Charismatic Renewal through the series of FIRE rallies (see chap. 1 n. 3) conducted independently of the national movement organization, in which the People of Praise remained prominent. Most important, leaders reconstituted around themselves a new network of like-minded communities and formally inaugurated the supercommunity the Sword of the Spirit. Member communities came under the jurisdiction of a translocal governing council with Steven Clark at its apex, and the communities' word gifts groups became a single translocal "prophecy guild" under the headship of Bruce Yocum. In the following year, the Servants of the Word brotherhood built the International Brotherhood Center as their global headquarters in Ann Arbor. The brotherhood zealously assumed the bulk of training and cultivating those affiliated groups who aspired to become full Sword of the Spirit branches.

Both external and internal difficulties arose in 1985–1986. Externally, an episode occurred that marked the moment of greatest tension

between the Catholic church hierarchy and the Charismatic Renewal in the nearly twenty years of the movement's history. The episode concerned, not Pentecostal ritual practices such as speaking in tongues, faith healing, casting out of evil spirits, or resting in the Spirit, but ecclesiastical jurisdiction over communities bound by covenant to the authority of the Sword of the Spirit. Branches in Akron, Miami, Steubenville, and Newark all encountered difficulties with the bishops in their local dioceses, but it was the latter that drew the broadest attention. The episode originated with the aforementioned creation within The Word of God of denominational fellowships equivalent to parishes but entirely contained within the covenant community. The Catholic fellowship was approved by the local bishop in the Ann Arbor case, and with the formation of the Sword of the Spirit as a single international community its governing council petitioned the Pontifical Council for the Laity in Rome for official recognition of such "fellowships" for Roman Catholics within covenant communities. Since in effect this was a request for creation of an entirely new ecclesiastical category, the Church moved slowly in its deliberations on the petition, and in the meantime each Sword of the Spirit branch had to request independent approval from its own local bishop.

When in 1985 the People of Hope branch submitted the statutes for their Catholic fellowship for approval to the bishop of Newark, they were rejected. Prominent among the reasons were irreconcilability between "submission" to any transdiocesan authority and the expectation of a bishop for authority over all Catholics within the geographic territory of his diocese. Also of concern was the ambiguous meaning of a "covenant" between Catholic and non-Catholic members of a community. The People of Hope appealed to Rome, which deferred to its yet incomplete consideration of the overall Sword of the Spirit petition. In the process the Newark bishop resigned, but a new bishop adopted essentially the same position, and the situation remained in a stalemate. Ten years earlier Clark (1976) had written that based on the precedent of "renewal communities" in earlier centuries of Church history, a covenant community challenged by a local bishop should consider moving to a more receptive diocese. However, the eventual possibility of a favorable outcome, combined with the practical dilemma of disposing substantial community property and moving more than a hundred adults, militated against this solution.[4] The People of Hope partially acquiesced, formally withdrawing from the Sword of the Spirit while continuing to send its coordinators as observers to meetings of the supercommunity's leadership.[5]

Internally, tensions provoked by implementation of the Training Course mounted. The intensity of behavioral restrictions created family tensions, particularly in two respects. First was the increasingly specific prescription of male headship and gender discipline. Second was the requirement on parents to supervise community children and teenagers, who were expected to refrain from worldly activities such as attending dances, listening to rock and roll music, or wearing blue jeans. The result was an exodus of community members comparable to that during the recommitment of 1975. One community district whose coordinator was especially strict in implementing Training Course teachings lost not only rank-and-file members but also the majority of its district heads. Ultimately even one of The Word of God's longtime head coordinators resigned and left the community. Circumstances were such that for the first time coordinators publicly "repented" for the secrecy and speed at which they had implemented the Training Course, though notably not for any of its contents or intended goals. In an effort to protect the community's reputation, Martin also held a meeting for "reconciliation" with former community members and formally repudiated what had become a de facto practice of shunning those who had renounced their public commitment.

However, the crisis over the Training Course had left a mood of self-assessment about the community's effort to create a culture for itself as a people. The interpersonal demands created by household clusters proved unworkable, and a return was made to small interpersonal groups, now segregated by gender, as the principal mechanism of intimacy. Certain elements of community practice perceived as isolating it and inhibiting its growth began to be modified. There were no longer community-sponsored block parties with evangelistic intent. Opposition to women working outside the home and to marriages outside the community began to ease somewhat. The term "head" was replaced (in official terminology if not in popular usage) by "pastoral leader" or "long-term elder." The stated reason for this change was the archaism of "headship," and, in the words of one head coordinator, its connotation to outsiders of "more substantial directive authority than we see in pastoral relationships." The physical aspect of the domestic environment was also moderated, with the decline of inscribed wall banners and the reintroduction of televisions, stereos, and videotape players, even if used only for religiously acceptable programming.

Coincident with the reaction to the Training Course, however, these years also saw the infusion of new energy into the ritual life of the community. As Derek Prince and Robert Mumford had done earlier in the

community's history, around 1985 Protestant evangelist and healer John Wimber visited The Word of God, bringing the practice of "power evangelism."[6] Wimberite prayer encourages manifestations of divine power in the form of "signs and wonders" such as healing, spontaneous waves of laughter or sobbing that spread through an assembly, and the falling in a sacred swoon known as resting in the Spirit. Wimber's emphasis on participants' laying on of hands for each other initiated a renewed interest in healing prayer among the community rank and file. This enthusiasm extended beyond already typical practices of informal healing prayer in households, within the personal headship relation, or by district heads and coordinators visiting the sick in their biblically defined role of community elders. Advocacy for making spiritual gifts of power more accessible to the rank and file also played a part in the initiation in 1986 of Charismatic prayer meetings for children at some Sword of the Spirit branches. Perhaps encouraged by the Wimberite influence, and acting on a longtime awareness that their retreat from the world to consolidate a Charismatic culture would make them less accessible to the general public and slow their rate of growth, the coordinators in 1987 also once again began to hold an open prayer meeting.[7] A new experiment was inaugurated in 1989 as several members of The Word of God relocated to Colorado to live alongside members of John Wimber's Vineyard Ministries, developing an order of life synthesized from covenant community pastoral forms and power evangelism forms of access to divinity.

By 1990 The Word of God branch of the Sword of the Spirit included fifteen hundred adults and an equivalent number of children, first among equals within the Sword of the Spirit and a powerful voice within Charismatic Christianity (see tables 6–8). In 1990, however, enduring tension within the international leadership of the Sword of the Spirit surfaced over, in the words of one community official, "differing visions of community structure and differences between strong, zealous personalities." Ralph Martin and Steven Clark represented the two factions, with Martin proposing that those communities who wanted more local autonomy but who wanted to remain within the supercommunity be allowed to assume a new status of "allied" communities. Through the traditional means of a "community consultation," the plan was submitted to The Word of God members, who reportedly had little forewarning that a serious rift had developed within the community elite. The majority of members and coordinators agreed on the move to allied status. However, Clark's brotherhood, the Servants of the Word, announced that they were an autonomous body not bound by

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

the community decision and that they would remain within the Sword of the Spirit. Several of the coordinators and a core of rank and file rallied around them and reconstituted as a new branch of the Sword of the Spirit. A schism had occurred.[8]

In 1991, of the presplit membership of approximately 1,500 adults, the Sword of the Spirit branch claimed 230 members. The Word of God claimed somewhere between 600 and 800. Perhaps reflecting the family tension over personal conduct associated with the Sword of the Spirit Training Course, it appeared that families with older children tended to remain in The Word of God and those with younger or grown children constituted the bulk of the new Sword of the Spirit branch. It also appeared that the diminished Word of God membership was roughly evenly divided among Protestant and Catholic (see table 9 for presplit proportions). The smaller Sword of the Spirit appeared to become predominantly Catholic in reaction to a perception of inordinate Protestant influence in The Word of God.[9] Rank-and-file Catholics from both communities continued to attend the denominational Christ the King fellowship, which as a result of the schism had been removed by the local bishop from within the community and declared to be a kind of non-geographic floating parish under direct diocesan jurisdiction. Perhaps 150 former community members chose to remain active in the fellowship without allegiance to either The Word of God or the Sword of the Spirit. From all indications the remaining four hundred to five hundred members, disaffected and disillusioned, terminated participation in any community-related activity.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Several issues underlie the overt split in the Sword of the Spirit over local autonomy versus centralized government. Most appeared to be a legacy of the crisis over the Training Course. The stance of Martin and The Word of God leadership was to "repent" for elitism and arrogance relative to other Christians. They also "repented" for internal abuses of authority in enforcing practices that, because of their rigor and the difficulty of conforming to them, led to unhealthy feelings of inadequacy among members. The stance of Clark and the Sword of the Spirit was

that they would remain faithful to the original divinely inspired community "vision," adhering to the substance of the Training Course while continuing to admit that it was awkwardly implemented. They see themselves as maintaining the structure of a covenant community, including headship, and The Word of God as retreating to the status of a sophisticated prayer group.

The Wimberite influence also proved to be a point of controversy. From the perspective of many members, this influence marked a kind of spiritual renewal within the community. However, Clark's faction construed the embrace of Wimber's power evangelism by Martin and Head Coordinator James McFadden as an abandonment of Catholicism. McFadden's collaboration with the Wimberites in founding a sub-community of The Word of God in Colorado was seen as an abandonment of the covenant community model in favor of Wimber's Vineyard congregations.[10]

A third issue is the recent popularity among rank-and-file members of twelve-step support groups based on the model of Alcoholics Anonymous and related "codependency" theory. Community interest in these groups coincided with their popularity in the broader North American society during the 1980s.[11] The Sword of the Spirit perceived them precisely as alien influences, incompatible with the pastoral structure of the covenant community and potentially creating "confusion" by offering support based on competing principles. Indeed, another branch of the Sword of the Spirit explicitly declared that anyone who joins such a group cannot be in the community. The Word of God saw the popularity of support groups as a sign of inadequacy and need for reform in their own structure of interpersonal support. They speculated that perhaps members were seeking support from tensions generated by community life itself, or that perhaps their mode of life attracted (or at least keeps) the kind of people who are in need of such support. In fact, twelve-step groups are by definition "anonymous," and may thus constitute not only a search for additional support but also reaction against the intense communitarian elaboration of the psychocultural theme of intimacy.

In 1992 The Word of God, while remaining an allied member of the Sword of the Spirit, adopted a dramatic set of reforms. Moreover, rather than use the old community consultation format, these changes were instituted as a result of direct democratic vote. The sweeping changes can be divided into categories of community life and membership, leader-

ship, and symbols of groups identity. I will summarize the changes in each category.

First, in an effort to restore mature responsibility for personal decision making to members, the community abolished the institution of pastoral leadership (headship), long a cornerstone of group organization. The system of "pastoral care" was to be replaced by one of "fraternal support." The Training Course was officially "set aside" as an "ill-advised venture" with much associated "bad fruit." Although its fundamental values were reaffirmed, members were advised to judge for themselves which elements to keep and which to reject. Even beyond this, the long series of initiation/indoctrination courses that prepared people for "public commitment" as full community members was to be modified and streamlined. The community in effect repudiated Steven Clark's formulation of group life by abandoning the key Living in Christian Community course, codified in Clark's book Patterns of Christian Community (1984). In the new model, the basic Life in the Spirit Seminar was to be followed only by a course on the Charismatic spiritual gifts and a course on community membership. Members voted to decrease the demands on the amount of participation and activity required of them. Leaders were to retain the ability to terminate members for denial of "Christian truth" or offense against "Christian righteousness," but termination for inadequate participation was reserved to a board the majority of which was to be rank-and-file members.

In the domain of leadership, it was voted that the current coordinators resign in favor of a newly constituted leadership team of five to eight members. This team would be chosen, advised, and overseen by a council of twenty-five members elected by the general membership. A proposal granting the "senior leader" of the leadership team a veto over team decisions was explicitly defeated in the vote. The most momentous change, however, was that women were to be included as voting members of both the leadership team and the council (six women were subsequently chosen as council members). A male was still to be the senior leader of the leadership team, of the council, and of small-scale support groups ("men's and women's" groups or "growth" groups), "as a way of expressing the leadership of men seen in the New Testament." Nevertheless, the importance of the change was evidenced in the inclusion of a vote about whether to delay inclusion of women as leaders, pending a ruling by the international governing council of the Sword of the Spirit as to whether the proposal would undermine the allied status of The

Word of God. The membership voted not to wait. In the words of one male leader, the consensus was that "in this time and place, it's appropriate to have women as leaders." The time and place, it will be noted, coincided with the confrontation in American society between Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas over the latter's Supreme Court nomination and with the confrontation between Desiree Washington and Mike Tyson over the latter's rape of the former, events that led to the emergence of the political scene of many prominent women as candidates for national office in the 1992 election.

The most profound change in symbols of community identity was abandonment of mantles and veils, which had been worn as a sign of public commitment. These items of ritual garb, which had distinguished members from outsiders and different classes of members within the community, were to be turned in "so that they can be disposed of respectfully." In addition, the members voted to consider whether to keep, modify, or drop the formal community covenant. Until such a decision was made, new members were given the option of committing to "simple membership" rather than "full commitment." Finally, members voted to consider changing the community name from "The Word of God" to something like "The Word of God Community." These latter two issues can be understood only by recalling that both the covenant and the community name were understood to have been bestowed directly by the deity and were therefore considered essential to the community's divine mission and its identity as a "people of God." To consider becoming merely a community named The Word of God, rather than continuing to be The Word of God, was anything but mere semantics.

What the possibility of a change in name indicated, along with the other changes in 1992, was the reversal of the rhetorical involution to which I referred earlier in this chapter. For years the community had avoided the process identified by Weber as the routinization of charisma with an ever-escalating rhetoric embedded in practice and performance. The schism in The Word of God was a kind of apocalyptic break, a crisis of the sacred self in which Clark's faction remained on the tightening spiral of charisma while for Martin's faction the tightening discipline, authority, and apocalyptic tension snapped like an overwound watch spring. In the next chapter we will examine the rhetorical process leading up to this apocalyptic break, filling in our ethnographic/historical sketch with a detailed account of the radicalization of charisma and the ritualization of practice.

Plate 1.

Community gathering of The Word of God in 1987. Participants are

arranged in concentric circles, with the central circle visible in the top

center of the image. The disposition of bodies in space retains the original

emphasis in Charismatic prayer meetings on the intimacy of

face-to-face interaction among participants seated in a circle. The

addition of concentric circles as gatherings grew in size, with community

leaders occupying the central one, did not replace the original sense of

intimacy but added that of the center as locus of authority toward which

participants were oriented.

Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Peter Yates photograph.

Plate 2.

Head coordinator Ralph Martin addresses the community gathering from

the center of the circle. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan,

Peter Yates photograph.

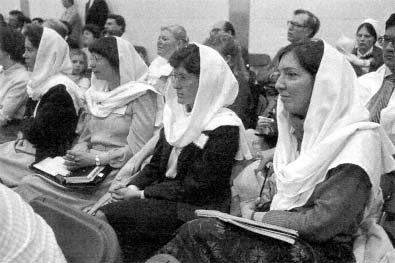

Plate 3.

Publicly committed women at the community gathering wearing veils

of Belgian linen.

Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Peter Yates photograph.

Plate 4.

Publicly committed men at the community gathering wearing mantles

of Irish linen. Following the community schism in the early 1990s,

use of mantles and veils was discontinued by The Word of God faction

on the grounds that it had contributed to exaggerated exclusivity, isolation,

and elitism. It was retained as a symbol of commitment by the Sword of

the Spirit faction.

Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, Peter Yates photograph.

Plate 5.

Community members engaged in loud praise, 1990.

Courtesy of Philip Tiews, The Word of God.