PART FOUR

THE WORKERS’ COMPANY

Seven

An Industrial Labor Force

Large companies like the PGC were primarily responsible for the transition from an artisanal to an industrial work force.[1] The results of the transformation require more investigation than they have yet received, since most labor studies have been concerned with craftsmen and their responses to changes at the workshop. Though historians no longer portray factory workers simply as the victims of the "dark, satanic mills"— utterly atomized, regimented, and undifferentiated—the present state of knowledge about the group is largely a matter of negative statements: industrial workers did not serve as the activists in the labor movement; they comprised a minority within the French working class; they were usually quiescent; when they did act, their protest was generally ineffective and poorly focused.[2] The industrial army that emerged at the gas plants was complex and underwent dramatic changes even in the absence of technological upheaval. Its evolution provides an opportunity to see factory workers in a more positive light.

[1] For an effort to conceptualize these types of work, see Michael Hanagan, "Artisans and Skilled Workers: The Problem of Definition," International Labor and Working-Class History, no. 12 (November 1977): 28-31.

[2] William Sewell, "Artisans, Factory Workers, and the Formation of the French Working Class, 1789-1848," in Working Class Formation: Nineteenth-Century Patterns in Western Europe and the United States , ed. Ira Katznelson and Aristide Zolberg (Princeton, 1986), pp. 45-70; Géard Noiriel, Les Ouvriers dans fa société française: XIX -XX siècle (Paris, 1986); William Reddy, Money and Liberty in Modern Europe (Cambridge, 1987), p. 208. Among the recent studies that will lead beyond the negative statements are William Reddy, The Rise of Market Culture: The Textile Trade and French Society, 1750-1900 (Cambridge, 1984); Donald Reid, The Miners of Decazeville (Cambridge, Mass., 1986); Michael Hanagan, Nascent Proletarians: Class Formation in Post-Revolutionary France (Oxford, 1989).

The Stokers

One reason for the failure to come to grips with the shift from artisanal to industrial labor is the complexity of the process. Occasionally employers were able to install machines and obliterate in a single blow craft-based production methods. This seems to have happened at the bottle plant in Carmaux, brilliantly described by Joan Scott. Supine machine tenders suddenly took the place of skilled glassblowers, who had trained for fifteen years to do their jobs.[3] Such a clean break was exceptional. Indeed, em-ployers even today have rarely succeeded in whittling down labor to a ho-mogenized, easily replaceable body of operatives doing simple, repetitive work.[4] Nineteenth-century factory work usually involved skilled workers doing crucial operations. Sometimes these were "industrial craftsmen," who had nearly complete control over the work process. More commonly, employers were able to subdivide craft work into simpler, but still skilled, activities. They also took control of hiring and training, usually leaving supervisors with these responsibilities.[5] Some new industries had never known an artisanal phase but revolved around skilled work of the latter sort. The replacement of artisans and industrial craftsmen by skilled workers was a long and gradual process. It was surely the central development in French labor history between the Commune and World War I.[6] The stokers who produced gas for the PGC provide an example of the type of factory laborer then coming to dominate production and protest.

The PGC was born rather advanced in terms of the social evolution of the labor force. A process-centered industry, gas production did not re-quire the fine shaping and fitting that assembling industries did. Though stokers performed the manual operations that were crucial to gas production, there was nothing intricate about their performance. Nor were there preindustrial traditions to stoking; the job arose with the nineteenth-century gas industry. Stokers did not have to adapt basic operations to particular circumstances, innovate at the job, or complete a multiplicity of

[3] Joan Scott, The Glassworkers of Carmaux (Cambridge, Mass., 1974).

[4] Patrick Fridenson, "Automobile Workers in France and Their Work, 1914-83,' in Work in France: Representations, Meaning, Organization, and Practice, ed. Steven Kaplan and Cynthia Koepp (Ithaca, N.Y., 1986), 514-547; Roger Penn, "Skilled Manual Workers in the Labor Process, 1856-1964," in The Degradation of Work? Skill, Deskilling, and the Labor Process , ed. Stephen Wood (London, 1982), pp. 90-108.

[5] Michael Hanagan, "Urbanization, Worker Settlement Patterns, and Social Protest in Nineteenth-Century France," in French Cities in the Nineteenth Century , ed. John Merriman (New York, 1981), p. 218; Lenard R. Berlanstein, The Working People of Paris, 1871-1914 (Baltimore, 1984), pp. 92-100.

[6] Reid, Miners of Decazeville , p. 72.

complex operations. They did the same task repeatedly and had only a small degree of autonomy too little for the concept of craft control to be relevant. Engineers and foremen set the parameters of the tasks and modified them at will.[7] The distinguishing feature of stokers, as skilled workers, was their market power. Not many humans could perform the strenuous work of stoking in the torrid distillation moms. And this was not the sort of work that an employer could allow to stop for very long. If pressure fell and air entered the gas mains, then the danger of catastrophic explosion was great,[8] Stokers found strategies for exploiting their market power in ways that differentiated them from common laborers and gave shape to the emerging industrial labor force.[9]

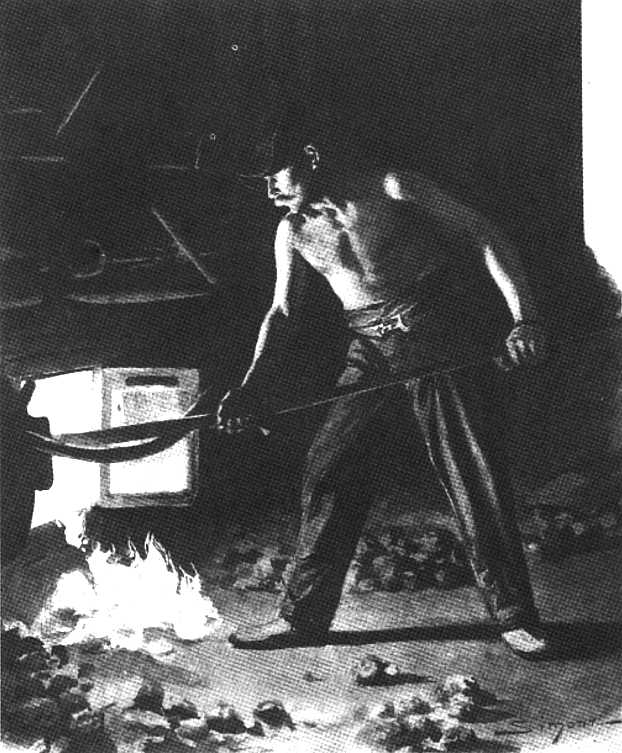

The banner of the union newspaper portrayed the stokers as barrel-chested, muscular giants, stripped to the waist and covered with coal dust and sweat. Outsiders who occasionally visited a distillation room never failed to be impressed by stokers at work. The oppressive heat, the strength required to fill a retort, the dexterity necessary for a neat job, and the physical dangers stokers abided filled visitors with admiration. The journalist Gustave Babin waxed eloquent at the sight of the PGC's stokers in action: "Athletes, for the most part, as they need to be to do such labor, these workers are superb to watch in action, in the play of reflexes they reveal. They have their special skills, their professional dexterities, which are marvelous. With great precision the stokers . . . know how to throw the shovelful of coal into a burning furnace, withdrawing their unprotected arm just as flames are about to lick it. With equally great poise they empty coke from the retort, projecting their heavy iron hooks into the incandescent tube."[10]

[7] AP, V 8 O , no. 764, "Main-d'oeuvre de distillation (26 avril 1870)"; "Etude des modifications à introduire dans la réorganisation dans le régime du personnel ouvrier de la distillation (29 avril 1870)." These two reports by the head of the factory division are the starting points for understanding the work situation of the stokers.

[8] Ibid., no. 161, report of Euchène, March 18, 1907.

[9] The industry-specific skills of the stokers made their positions analogous to those of the elite of mining teams, the hewers and timbermen, as well as to puddlers in the steel industry. See Rolande Trempé, Les Mineurs de Carmaux , 1848-1914, 2 vols. (Paris, 1971), 1:112; Reid, Miners of Decazeville , pp. 72-78; lean-Paul Courtheoux, "Privileges et misères d'un métier sidérurgique au XIX siècle," Revue d'histoire économique et sociale 37 (1959): 159-189. For the argument that nineteenth-century industry created many new types of skilled workers, see Raphael Samuel, "Workshop of the World: Steam Power and Hand Technology in Mid-Victorian Britain," History Workshop 3 (1977): 6-72.

[10] " Le Gaz d'éclairage," L'Illustration, no. 3084 (April 5, 1902): 251-253. An-other admiring observer was Léon Duchesne, Hygiène professionnelle: Des Ouvriers employes d la fabrication du gaz de l'éclairage (Paris, n.d.).

A stoker firing the furnace. From L'Illustration, no. 3084 (April 5, 1902).

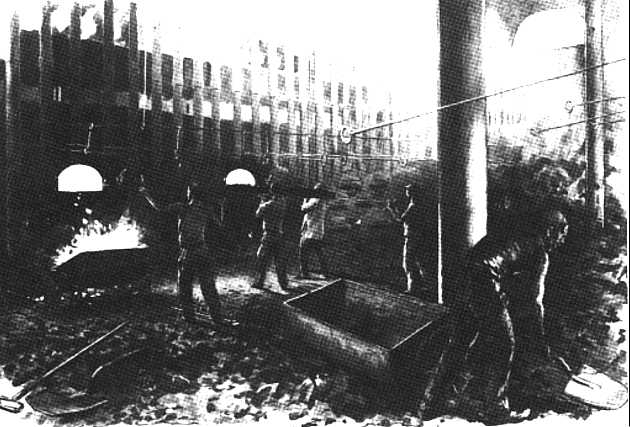

The entire operation of stoking consisted of several distinct activities, none of them easy and each with its particular physical demands and threats. First, the workmen brought several hundred kilograms of coal from the coal yard to the distillation room and pulverized it. The preparation of a hot retort for charging could be hazardous or at least noxious. Gas that had not escaped into the evacuation pipes might back up into the stokers' faces and burn or suffocate them. To prevent that, workers would open the mouth of a retort carefully and ply a glowing piece of coke so as to burn off the remaining gas. Then shoveling could commence. This op-

Stokers at work: shoveling, loading coal with a scoop, and

emptying the retorts. From L'Illustration, no. 3084 (April 5, 1902).

eration involved propelling heavy shovelloads of coal into a retort in such a way as to fill it evenly. Obviously, practice and dexterity were needed. During the four to six hours of roasting, a special stoker, the fireman, kept the furnace filled with fuel (usually coal or coke). In the meantime, other stokers had to pay attention to the evacuation pipes. When they became clogged with condensed residues (especially naphthalenes), a stoker had to clear them—quickly—with steam. Blockage produced frequent emergencies and not a few incidents of scorched skin. When distillation ended, the job of the stokers was to clear the retorts of the coke that carbonization had produced. This operation, one Babin especially admired, was per-formed with a heavy iron pole that had a ring on the end. It weighed eighteen kilograms, and workers had to manipulate it in the long, hot tube in such a way as to remove the coke without unnecessarily scratching the surface of the retort. They used the pole to push the burning coke into a wagon, which they then wheeled to the yard, where it could be extinguished,[11] In the opinion of some observers, transporting the burning coke was the most hazardous activity stokers did since occasions for being burned were numerous. Reports on work accidents confirm the assessment of danger. At the PGC's largest factory, La Villette, stokers were ob-

[11] AE V 8 O , no. 764, "Etude des modifications."

ligated to push wagons of coke seventy meters back and forth eighteen times during each charge.[12]

Stokers also had maintenance chores that complicated the job. Firemen were responsible for the care of their furnaces and had to remove the cinders after each charge. Such upkeep had to be done faithfully for the state of the furnace determined how hard the work was and how much stokers earned.[13] Stokers checked the retorts for fissures in the walls between charges and repaired them by spreading molten earthenware with an iron pipe. The inspection of evacuation pipes was also an important part of the maintenance activities.

Such labor was all the more difficult in that it was performed under debilitating circumstances. Temperatures in the distillation rooms rarely fell below 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and stokers were continually exposed to heat radiated from glowing surfaces. Director Camus cited the heat as the principle reason the job was beyond the capacity of most wage earners.[14] Work in the distillation rooms during the summer was reputed to be especially painful, but it did have one advantage over winter work: when stokers wheeled coke into the yard during the cold weather, the sudden change of temperature contributed to illness.

For obvious reasons the PGC needed men of rare physical endurance. Ideally, the physical giants who did stoking should also have had the dexterity for packing coke tightly.[15] In all probability the company could not insist on perfection in packing the retorts and had to settle for men who could do the work with minimal competence. One factory manager used the term "apprenticeship" to describe the training of a potential stoker. The exercise entailed setting up a retort in the courtyard and having the fledgling practice filling it with the shovel. The superintendent went on to

[12] Ibid., no. 717, 'Voles ferrées"; no. 151, report of Aline to director, May 11, 1897; no. 718, report no. 120, June 21, 1873. There were easier and less dangerous ways to handle the burning coke, but the company chose the method that would preserve the most value for its sale to domestic customers. For the work accident records of the La Villette plant, see AP, V bis 19 Q6 .

[13] AE V 8 O , no. 764, "Etude des modifications"; no. 151, report of Euchène, November 11, 1898.

[14] Compte rendu des travaux de la commission nominee par Monsieur le Ministre de l'Intérieur le 31 janvier 1890 en exécution de l'article 48 du traité entre la ville de Paris et la Compagnie parisienne de l'éclairage et du chauffage par le gaz (Paris, 1890), p. 139.

[15] One superintendent wrote, "The proper or improper execution of charging determines the yield of gas from a given quantity of coal and at a given temperature." Inexperienced stokers raised the cost of production 20 percent during the strike of 1890. AE V 8 O , no. 148, report of Cury to director, June 25, 1865; report of Gigot to director, October 8, 1892.

underscore the overwhelming importance of endurance by pointing out that such an apprenticeship was "as much physical as manual."[16] He no doubt meant that building stamina was crucial. The superintendents did not expect more than one in ten common laborers to be able to perform the infernal work.[17]

The harsh conditions meant that a stoker could not grow old in this line of work. The PGC's engineers professed to know hardly any who worked at the job for more than fifteen years or beyond the age of fifty.[18] Stokers inevitably spent the last third of their working lives as common laborers. If they tried to extend their careers at the furnace a year or two beyond their capacity, they paid dearly. One stoker wrote poignantly and from experience that "the last years on the job are the hardest times in a stoker's life."[19]

The evolution of stoking within the PGC illustrates how a job characterized by stable production methods could undergo profound transformation. A stoker of 1850 would have been disoriented by the work his comrade performed thirty years later. The very meaning of the stokers' work in relation to the rest of their lives had shifted over that generation. We can understand the transformation as a change from relative independence from the gas industry as a source of employment to dependence on the industry, and on the PGC in particular, for a livelihood.[20]

By any standards and under the best of circumstances the stoker's work was debilitating, yet it became far more so during the PGC's first decade of operation. The rationalization of production during the 1860s was responsible for the deterioration of conditions (see chapter 4). At that time the company became aware of the benefits of hot roasting. Raising the temperature of distillation allowed the firm to increase the number of charges per day, the size of the retorts that had to be filled, and the amount of coal in each retort while still producing gas of sufficient quality for lighting. The implementation of hot roasting caused unit labor costs to plummet and output per stoker to soar, all achieved without any mechanization whatsoever. When the PGC began operations in 1855, its factories completed only four charges in a twenty-four-hour period. Each furnace had no more than four retorts, and sometimes only one, to heat.

[16] Ibid., no. 148, report of Jones, April 26, 1865.

[17] Ibid., "Chantiers à coke"; "Union des agents principaux des chantiers h coke (19 novembre 1892)," p. 6.

[18] Ibid., no. 151, "Etat nominatif des chauffeurs ayant été conservés tout I'été."

[19] Ibid., no. 150, "Affaire Mercier."

[20] I have borrowed the concept of dependency from David Brody, Steelworkers in America: The Nonunion Era (New York, 1960).

Those vessels were short (two meters in length) by later standards.[21] Stokers did not have an easy job, but the demands of work were far less than they would soon become. An indication of the endurable pace of labor before 1860 was that stokers did twenty-four-hour shifts, working every other day. They were able to do so because they had time to rest and sleep (on piles of coal) between the six-hour roasting periods.[22]

The rationalization of production initiated by factory chief Arson soon brought the number of charges per day up to six, one every four hours. Stokers packed 100-120 kilograms instead of 75 kilograms of coal into each retort for each charge. Thus, with hot roasting the amount of coal stokers handled per day nearly doubled between 1860 and the late 1870s and continued to increase through 1905:[23]

Year | Kg. Coal per Stoker | Year | Kg. Coal per Stoker |

1860 | 1,460 | 1879 | 2,868 |

1864 | 2,131 | 1889 | 3,098 |

1867 | 2,526 | 1891 | 3,140 |

1868 | 2,572 | 1893 | 3,120 |

1877 | 2,874 | 1899 | 3,206 |

1878 | 2,891 | 1905 | 3,250 |

Maurice Lévy-Leboyer has argued that gains in productivity during the Second Empire usually resulted from intensified deployment of labor rather than from an increase in capital, and such was the case for stoking at the PGC.[24] The higher quantities of coal roasted depended entirely on the stokers' exertions.

Not only were stokers working much harder; they were doing so under increasingly adverse conditions. Hot roasting raised the heat under which stokers had to exert themselves, all the more so when Siemens furnaces were introduced. Superintendents reported temperatures of 120 degrees Fahrenheit in the distillation rooms when it was only 56 degrees outside.[25]

[21] AP, V 8 O , no. 709, report of Servier to director, May 7, 1860.

[22] Ibid., no. 148, report of Letreust, April 29, 1865.

[23] Ibid., no. 763, "Tirage des cheminées (28 avril 1869)'; nos. 148, 151, 159, 163, 709, 711, 716, 768, 1520.

[24] Maurice Lévy-Leboyer, "Capital Investment and Economic Growth in France, 1820-1930," in The Cambridge Economic History of Europe (Cambridge, 1978), 7 (1): 267.

[25] AP, V 8 O , no. 675, deliberations of May 8, 1872. Another report put the temperature at 115 degrees Fahrenheit when it was 75 degrees outside. Ibid., no. 768, "Usine de Saint-Mandé" report of April 18, 1869.

Moreover, the greater number of charges per day necessitated quicker emptying of the retorts and unloading of the coke. It also made the job of clearing the retorts more difficult because the burning coke dung to the sides.[26] At the same time, maintenance chores became more troublesome and time-consuming. Hot distillation caused a much more frequent clogging of the evacuation pipes. Furnaces and retorts were also harder to keep in good repair. Rest time between the more closely spaced charges was thus severely squeezed. Indeed, some observers asserted that there was no longer any rest time.[27]

The company contrived to rearrange work patterns so as to derive all the benefits it could from hot roasting. It broke down some of the stoker's work into specialized operations. Up to the 1850s stokers, working in teams, would take turns charging, clearing, moving the coke, and firing the furnace. Each of these steps had its distinctive demands, and stokers tried to even the burdens by exchanging tasks. The company forced the stokers to specialize in one of these operations.[28] The introduction of the Siemens furnace was another way the company gained more control over production. With simple furnaces the temperature of distillation de-pended entirely on the firemen: they could sabotage hot roasting at will by withholding fuel from the furnaces. The Siemens furnaces, however, were not really under their control.[29] Another change in the stoker's work pattern was the abandonment of the twenty-four-hour shift. Workers could not exert themselves for so long over so many consecutive hours, and the twelve-hour shift became the rule (except in one or two plants). Workmen resented this change because the twenty-four-hour shift had allowed them to rest or take other jobs on their off days.[30]

Thus, by 1870 the work of stokers had deteriorated drastically. Indeed,

[26] Compte rendu des travaux de la commission nominée . . . le 31 janvier 1890 , p. 39. The engineers who authored this report affirmed that stokers much preferred to work with ordinary furnaces.

[27] AP, V 8 O , no. 670, deliberations of May 25, 1864. Babin, the journalist who observed the stokers at work, remarked on the absence of a rest period. "Gaz de l'éclairage," p. 14. Even a superintendent was skeptical that stokers had much of a rest between charges. See AP, V 8 Oé, no. 160, report of superintendent of Ivry plant to Euchéne, July 16, 1899.

[28] AP, V 8 O , no. 764, "Main-d'oeuvre de distillation (26 avril 1870)"; no. 709, report of Servier to director, May 7, 1860.

[29] Ibid., no. 711, report no. 43, "Règlement du salaire de la distillation"; Compte rendu des travaux de la commission nominee le 4 février 1885 en execution de I'article 48 du traité intervenu le 7 février 1870 entre la ville de Paris et la Com-pagnie parisienne de I'éclairage et du chauffage par le gaz. Procès-verbaux (Paris, 1886), p. 189.

[30] AP, V 8 O , no. 764, report of April 29, 1870 (fols. 18-21); no. 768, "Usine Passy,' report of December 2, 1860.

it is hard to find a similar tale of deterioration in the annales of French labor history Skilled workers were not usually passive as their work be-came degraded. They fought and usually drew employers to a standoff long before their work load had increased to the extent the stokers' had. Were stokers an anomalous case, or did they exemplify the helplessness of industrial workers—even skilled ones—in the face of a determined employer?

To the extent that historians have examined that industrial work force, they have concluded that the group was helpless either to resist employers' demands or to find an organizational and ideological basis for the resistance.[31] The sociologist Craig Calhoun provides a theoretical argument that purports to explain the malleability of the factory operative in contrast to the craftsman. Calhoun's formulation shifts the emphasis from resistance to adaptation.[32] He posits that skilled industrial workers, unlike artisans, were not inalterably opposed to industrial development by their very way of life. Whereas artisans had to defend the craft basis of production, skilled factory workers could use their ability to create bottlenecks at crucial steps in production to bargain with their employers. Calhoun believes that industrial workers naturally took advantage of capitalistic development to obtain improvements in their earnings and living conditions. Calhoun's model of bargaining is applicable to the stokers, who were not at all helpless before their bosses. They did use their market power to obtain immediate material gains in exchange for greater output. Such comportment, however, characterized stokers in a particular phase of their development. The model of adaptation was not relevant under all circumstances, and stokers altered their strategies as the role of work for the PCG in their lives changed. Calhoun did not see that skilled industrial workers, French ones at least, had the capacity to become more like craftsmen in their confrontations with managerial authority.

The shop floor in and of itself provides too narrow a perspective for understanding how stokers evaluated their options on the job. Their re-action to the rationalization of gas production depended, at least in part, on their way of life.[33] Stokers were one example of the sort of factory

[31] Scott, Glassworkers of Carmaux, chap. 7; Yves Lequin, Les Ouvriers de la région lyonnaise (1848-1914), 2 vols. (Lyon, 1977), 2:242-348; Michael Hanagan, The Logic of Solidarity: Artisans and Industrial Workers in Three French Towns, 1871-1914 (Urbana, Ill., 1980).

[32] Craig Calhoun, The Question of Class Struggle (Chicago, 1982).

[33] Michael Hanagan demonstrates the importance of integrating a consideration of the workers' private lives into their work histories in "Proletarian Families and Social Protest: Production and Reproduction as Issues of Social Conflict in Nineteenth-Century France," in Work in France , ed. Kaplan and Koepp, pp. 418-456.

workers who did not rely on one and only one kind of labor for permanent, year-round employment. The gas industry was highly seasonal be-cause of the limited contours of consumption: the number of stokers needed for production in July was only about 55 percent of that required in January. Stokers were very much part of a floating population that alternated between factory work and other activities, often rural employment. In 1865 the assistant chief of production, Servier, stated that "nothing attaches the stokers to the company. Our jobs are for them a pis aller, and they often prefer to earn less while working in the open air."[34] Three decades later the journalist Babin was still able to describe the stokers as "Bretons and Auvergnats, for the most part, who come to spend winter in the hellfires of Paris, when the earth enters its annual sleep, and who, at the first springtime sun, return to a much healthier life in the country."[35] This description, a rough approximation of reality at best, captures an important truth: stoking was only a part of the working lives of the stokers.

As members of a floating population, the stokers were by no means a special case of industrial workers. The convention of dividing social phenomena into urban and rural is often highly misleading. Yves Lequin has shown that temporary transfers of population between the countryside and the city provided a major part of industrial labor through most of the nineteenth century. "Industry founded its takeoff" Lequin writes, "on the periodic use of a circulating labor force more than on the assembling of a fixed force."[36] The phenomenon was a consequence of a pattern of rural proletarianization that was quite pronounced in France. The countryside had long known a proliferation of very small holdings, and cultivators had to supplement their incomes, often through temporary emigration and seasonal industrial activity Rural population growth also produced underemployed village artisans, who sought seasonal work in cities. On the demand side, small and irregular markets for industrial goods made a large, permanent industrial labor force unnecessary. In the end, gas production was unexceptional in its seasonality and its use of a floating labor force. The stokers were not at all peculiar as peripatetic proletarians.

The stokers' acquiescent response to the rationalization of production until the 1880s must be understood in the context of their relative independence from the PGC. The good pay that the gas firm offered for part of

[34] AP, V 8 O , no. 148, report of Servier, June 20, 1865.

[35] "Le Gaz de l'éclairage," p. 252. On the seasonality of gas production, see Frank Popplewell, "The Gas Industry," in Seasonal Trades , ed. Sidney Webb and Arnold Freeman (London, 1912), pp. 148-209.

[36] Lequin, Ouvriers de la région lyonnaise , 1:vii; Noiriel, Ouvriers dans la société française , pp. 44-55.

Table 18. Geographical Origins of Stokers, 1898a | ||

Region | No. | % |

Auvergne | 40 | 29.0 |

Brittany | 27 | 19.6 |

Centerb | 15 | 10.9 |

Limousin | 14 | 10.1 |

Alsace-Lorraine | 12 | 8.7 |

Champagne | 9 | 6.5 |

Normandy | 8 | 5.8 |

Paris (city) | 7 | 5.1 |

Paris (region) | 6 | 4.3 |

Total | 138 | 100.0 |

Sources: AP, V 8 O1 , nos. 151, 160; electoral lists for the thirteenth, fourteenth, fifteenth, and nineteenth arrondissements. | ||

a The available sources limited the sample to stokers at the lvry, Vaugirard, and La Villette plants. | ||

b Departments of Nièvre, Saône-et-Loire, and Cher. | ||

the year was an attractive option for the stokers, but it was not their only option. Their commitment to stoking as an occupation was conditional on being able to earn more than through other lines of work. Such was the instrumental logic of their employment with the PGC.

The stokers were essentially rural people in background and in habits. The earliest electoral lists for the neighborhoods they inhabited show that the vast majority came from the provinces, usually the deep provinces (table 18). Almost all were born in villages. They could not follow the pattern of some industrial workers, who settled near factories and begat a second generation of laborers sur place. The special "skills" stokers had, unusual strength and endurance, could not become a family legacy; and stokers might have wanted less demanding jobs for their children, anyway. Thus, each generation of stokers was constantly renewed from rural France, not from established factory communities.[37]

In the early years of the gas industry stokers seem to have organized

[37] For the more common case of immigrants who eventually established a community around the factory, see Lenard R. Berlanstein, "The Formation of a Factory Labor Force: Rubber and Cable Workers in Bezons, France (1860-1914),' Journal of Social History 15 (1981): 163-186.

their lives in a manner similar to that of the better-known "Limousins,' or building workers from that province. These masons left home each year to spend the winter in Paris and rarely renounced being cultivators. Their ultimate goal was to put aside money to survive as farmers or to save up enough to round out their plots.[38] The geographical origins of the stokers tied them to the same world of proletarianized peasants. As we have seen, Babin assumed that most stokers were still peasant-workers who, even at the dawn of the twentieth century, returned to their farms each spring. That might have been true at one time, but growth and change in Paris during the Second Empire interrupted the pattern. The PGC's engineers noted agricultural labor as one alternative for stokers, but construction in Paris provided another option, probably a more important one by the 1860s. Various building activities were viable for stokers because of the seasonal patterns, the relatively high pay, and the physical requirements. Some stokers also went into the brickyards for work during the warm season. Most often the PGC expected to lose stokers to masonry, ground clearing, and foundation work.[39] Opportunities to take jobs in construction were plentiful in the Paris of Baron Haussmann.

Because stoking was not a permanent occupation but rather a part of an economy of makeshifts, often with an agrarian component, stokers acted with a great deal of independence regarding their employer. Thus, the Auvergnat Pierre Garrigoux had to be rehired eight times between July 1876 and March 1880. He had departed voluntarily seven times and was laid off only once. His leadership in the 1880 strike effort finally cost him his job with the PGC.[40] The most visible manifestation of this independence vis-à-vis the gas industry was the paradox that the PGC had a shortage of stokers during the season it needed the fewest. The difficulties in recruiting a sufficient number of stokers were greatest in July and August, when gas consumption was at its lowest point of the year. At the root of the paradox was the stokers' practice of leaving gas plants to take jobs in construction or returning to the farm, both of which were then at their peak of activity. During the moments of especially powerful demand for labor in construction, gas engineers complained that stokers left even before winter ended so as to get the best-paying jobs at building sites. There they

[38] Alain Corbin, Archaïsme et modernité en Limousin au XIX siécle (Paris, 1975); David Pinkney, "Migrations to Paris during the Second Empire," Journal of Modern History 25 (1953): 1-12; Gabriel Désert, "Aperçue sur l'industrie fran-çaise du bâtiment du XIX siècle," in Le Bâtiment: Enquête d'histoire économique, XIV -XIX siècles, ed. Jean-Pierre Bardet et al., (Paris, 1971), 35-119.

[39] AP, V 8 O , no. 148, report of Jones, April 26, 1865; report of Gigot, April 30, 1865; report of Letreust, April 29, 1865; report of Servier, June 20, 1865.

[40] Ibid., no. 150, "Affaire Garrigoux."

could earn as much, or almost as much, as in the distillation rooms while escaping the frightful physical toll of a summer near the furnaces.[41] Stokers further asserted their independence from the gas company by resisting the shift from a twenty-four-hour to a twelve-hour day. As late as 1870 a particularly acute shortage of stokers forced the PGC to offer a return to the old schedule to attract more workers.[42]

The independence signals what stokers cared about most in working for the PGC—earnings. Stokers did not constitute an occupational community rooted in a craft. They did not define their status in terms of mastery at the workplace. Distilling coal was a way of scraping together income. Alain Corbin has identified the "ferocious will to save" as the guiding rule of the Limousins, and the same point applied to the stokers.[43] The quest to maximize earnings was the focus of their working lives, and it created both areas of compromise and areas of conflict with the company. On the one hand, managers were eager to raise productivity and the stokers were willing to accommodate, for a price. On the other hand, the engineers' moral view of wages did not honor the principle that harder work necessarily deserved greater compensation.[44] Thus, there was a large potential for conflict between management and the workers even though the latter accepted the tradeoffs inherent in the logic of capitalism.

<><><><><><><><><><><><>

The reports of factory superintendents to their superiors during the 1860s place the role of labor into perspective. The managers apparently regarded neither the supply of workers nor their malleability as major concerns. Superintendents rarely noted that workers refused to increase their output or alter their routines. Even complaints about shortages of stokers were sporadic, not chronic. The manager of the Ivry plant pointed out in 1862 that the booming construction industry for the most part helped the PGC find stokers, for it attracted many hands to Paris, and they needed work in the winter. Other problems preoccupied the superintendents far more than labor: the quality of the coal, the supply of well-

[41] Ibid., no. 674, deliberations of April 30, 1870; no. 148, report of Jones, June 26, 1865; report of Philippot, April 25, 1865. The stokers could have remained with the PGC, working in the courtyard, if they had been content to earn only 3.25 francs.

[42] Ibid., no. 674, deliberations of April 30 and May 4, 1870. The Belleville plant ran on twenty-four-hour shifts until 1874. See no. 677, deliberations of December 12, 1874.

[43] Corbin, Archaïsme et modernité, p. 205.

[44] See chapter 4. For a theoretical perspective on consensual relations in industry, see Michael Buraway, Manufacturing Consent: Changes in the Labor Process under Monopoly Capitalism (Chicago, 1979), which underscores the contingent nature of workers' consent.

constructed retorts, and the state of the equipment. Labor agitation occurred from time to time, but managers would hardly have been inclined to define industrial relations in terms of a crisis, as they would in 1899.[45]

The distilling halls of the PGC were disturbed by strikes or by serious threats of strikes roughly every other year between 1859 and 1869. Peasant-workers though they may have been, the stokers had no trouble cooperating with one another and making the company aware of their discontents. In each biennial action they forced the company to give them a raise. Between the founding of the PGC, in 1855, and the Franco-Prussian War stokers had obtained a 70 percent increase in their pay. Several forces were driving their agitation. The cost of living had risen sharply in Paris, and stokers were in part safeguarding their purchasing power.[46] At the same time, stokers were demanding compensation for their greater exertion on the job. Inflation and harder work may have formed the basis for the common understanding that allowed stokers to take collective action, but they did not determine the timing or the form of the strikes. These aspects of collective protest derived from the stokers' independent status. Stokers struck when they could take advantage of their attachments to the construction industry.

The labor agitation in the PGC up to the 1880s coincided with peaks in building activity.[47] Through the nature of their strikes the stokers re-minded the company of their independence from it. In "classic" strikes, workers withhold their labor and inform their employer what it would take to bring them back to the factory. The stokers instead staged a collective act of quitting and left en masse for jobs on construction sites. That is why all the strikes of the 1860s took place in the spring or summer, at the time of hiring for construction but in the dead season for gas production. Apparently, the stokers did not always specify the conditions that would keep them at the plant.[48] Such practices might appear "archaic," the action of workers who were not fully inured to the industrial process or who possessed a "preindustrial mentality"; but they were nothing of the

[45] See the collection of reports from the plant superintendents, AP, V 8 O , no. 768; no. 148, report of Gigot, April 30, 1865.

[46] On price levels in Paris, see Alain Plessis, De la fête impériale au tour des fédérés (Paris, 1979), p. 93.

[47] On building activity in Paris, see Françoise Marnata, Les Loyers des bourgeois de Paris, 1860-1958 (Paris, 1961), and Jacques Rougerie, "Remarques sur l'histoire des salaires à Paris au XIX siècle," Le Mouvement social, no. 63 (1971): 71-108.

[48] For examples of early strikes, see AP, V 8 O , no. 148, "Grève et réclamations"; no. 1286, report of superintendent of Ternes plant to Arson, April 26, 1867.

kind.[49] The stokers' form of striking was a rational strategy arising from their position vis-à-vis the gas industry. The action might also have been designed to avoid the harsh treatment that the company reserved for strikers. Instead of firing them for making trouble, the superintendent had to convince them to remain by offering concessions, so

The object of collective action was not yet a complex matter of control but rather a matter of pay. The stokers were willing, perhaps eager, to labor harder provided they received higher compensation (table 19). Whether they were paid by the day or by the amount of coal distilled did not seem to make a difference to the stokers; they preferred the mode that would bring them the most income. The rationalization of gas production met with little opposition from the skilled workers because they aspired to maximize gains from lucrative work that was available for only part of the year The raise did not even have to be proportional to the increase in exertion. When the PGC took over a gas plant near the suburb of Saint-Mandé, stokers demanded the pay level that prevailed in the company's other plants, which meant a raise of twenty-five centimes a day (6.7 per-cent). The new superintendent yielded to the demand only after he reorganized teams so that five men would have to do the work that six did formerly. Despite the imbalance between the raise and the increased labor extracted, no further trouble occurred. Indeed, the superintendent re-ported that the stokers were quite happy with the arrangement.[51]

Superintendents were often surprised by the amount of work they could extract from stokers by according a small raise. The manager of the Passy plant had not been happy about giving the stokers twenty-five centimes more per day in 1859, for it meant they were escaping the internal labor market he had aspired to construct. Nonetheless, he appraised the results of the raise with satisfaction. Not only was the superintendent able to replace the popular twenty-four-hour shift, but he was also able to introduce charges every four hours. Thus, the 7 percent raise yielded a 55 percent increase in coal distilled.[52] At the same factory nine years later, another acute labor shortage compelled the superintendent to offer the stokers a choice of work routines. They could continue at the same pay and load short (2.5 meter) retorts, requiring seventy-five kilograms of coal

[49] For intriguing efforts to link the form of collective protest to workers' culture, see Reddy, Rise of Market Culture, chaps. 7, 10; Michelle Perrot, Workers on Strike: France 1871-1890 , trans. Chris Turner (New Haven, 1987).

[50] Organizers of collective protest were inevitably fired, if not at once, then at a convenient moment.

[51] AP, V 8 O , no. 768, "Usine Saint-Mandé."

[52] Ibid., "Usine Passy." The manager reported producing 249,000 cubic meters of gas a day in 1861 and only 160,000 in 1859.

Table 19. Average Daily Pay of Stokers (in francs) | ||

Year | Mode | Wage |

1855 | By day | 3.50 |

1859 | By day | 3.75 |

1863 | By day | 5.00 |

1866 | By day + 50 c. bonus | 5.50 |

1869 | 5 f./day + 20 c. per 100 kg over 2,500 + bonus | 5.95 |

1879 | 5 f./day + 20 c. per 100 kg over 2,500 + bonus | 6.20 |

1881 | 3 f. per 1,000 kg + bonus | 8.95 |

1889 | 3 f. per 1,000 kg + bonus | 9.30 |

1893 | 3.3 f. per 1,000 kg | 10.30 |

1899 | 3.3 f. per 1,000 kg | 10.50 |

Sources: AP, V 8 O1 , nos. 148, 711, 748. | ||

per charge, or they could load long (2.75 meter) retorts, taking a hundred kilograms of coal, and receive a raise of twenty-five centimes. The stokers chose the higher pay even though they were not going to be fully compensated for their exertion.[53] On two occasions at least, in 1865 and 1870, top production managers believed that stokers had reached the limits of human endurance and that productivity could climb no higher without basic changes in the work process.[54] Yet output per worker continued to rise without resort to mechanization, though more slowly than in the past. The incentive bonus introduced in 1869, twenty centimes per hundred kilograms of coal over twenty-five hundred kilograms distilled, apparently motivated stokers to boost output.

Though wages were the stokers' principal focus at the time, there were other issues that could unite them. Cury, the ancient superintendent of the La Villette plant, once sought to improve the lighting power of coal by treating it with heavy oils derived from coal tar. The stokers refused to abide the experience because the odor of the oil made them ill and the treated coal stuck to their shovels. Curd had to abandon the initiative.[55] Likewise, firemen occasionally resisted the endless experiments with dif-

[53] Ibid., no. 749, report of superintendent of Passy plant to Arson, April 6, 1869.

[54] Ibid., no. 764, "Main-d'oeuvre de distillation (26 avri11870)"; no. 148, report of Gigot, April 30, 1865.

[55] Ibid., no. 768, "Usine de La Viilette,' report of December 15, 1861.

ferent sorts of fuels.[56] The work routine on Sunday was another source of friction. The company attempted to make the stokers on the day shift work a full night shift too. The stokers successfully united to compel the company to accept four charges on Sunday instead of six.[57] These incidents suggest that stokers had the potential to stop or at least curtail the dramatic changes that management made in the work routine during the 1860s, but the workers did not apply their collective power to that goal.

In addition to seeking more pay, even at a high cost to themselves, the stokers held the company to a rudimentary sense of justice entailing equal pay for equal work. Rumors that stokers at another plant were earning more sparked some agitation. But the stokers were never completely successful in standardizing wages among the different plants because work routines and output differed from one to another. Furthermore, the company often succeeded in keeping them ignorant about pay levels outside their small spheres.[58] On the other hand, the stokers quickly disposed of corporate plans to impose on them the career-based pay under which unskilled workers suffered. The company tried in 1858 to create three "classes" of stokers, with twenty-five-centime differences for each step, but agitation forced management to back away from the attempt within a few months.[59]

Lacking from the stokers' repertoire of collective protests were con-frontations with supervisors over unwelcome interference, insults, tests of will, and the like. The records on labor from the 1860s and 1870s, ad-mittedly incomplete, contain no reference to such conflicts.[60] The absence is all the more noteworthy in that the stokers' increasing productivity was achieved through closer supervision, badgering, and pressuring from fore-men. The number of immediate supervisors increased significantly. In 1858 there was one foreman for every thirty-seven distillation workers; in 1884 the ratio was one to twenty-three. Stokers may have resented the increased supervision but they had to deal with it as individuals, quitting or standing up for themselves. In view of the trouble that foremen would cause by the end of the century, the absence of such conflicts is telling.[61]

[56] Ibid., "Usine Ternes,' reports of September 16 and 23, 1860.

[57] Ibid., "Usine Beileville,' report of April 14, 1861; no. 717, report no. 95, Rigaud to Arson.

[58] Ibid., "Usine Passy,' report of April 14, 1861; no. 151, report of Arson to director, May 1, 1890.

[59] Ibid., no. 666, deliberations of August 3, 1858, and March 9, 1859.

[60] Ibid., no. 768; no. 148, "Rdponses aux demandes concernant le personnel." Engineer Audouin reported no more than two or three suspensions a year for rebellious behavior.

[61] Ibid., no. 665 (fols. 500-514); no. 153, "Personnel." On agitation against the authority of the foreman at the end of the century, see chapter 8.

The stokers clearly created consternation among management by defeating its plans for an internal labor market. Nonetheless, these physical giants proved pliant in serving the larger interests of the firm. The managers' complaints about "outrageous" demands were a sign of having been spoiled by fortunate circumstances.[62] Ultimately, engineers implicitly recognized their good fortune and showed it by tolerating wage demands without seeking to weaken labor's power through technological displacement. Over the long run, however, the firm's advantageous position was destined to disappear. It was not that stokers suddenly became "class-conscious." Rather, the conditions that kept them independent, interested primarily in higher wages, and responsive to the carrots and sticks that managers chose to wield ended during that prime transition point in Parisian social history, the economic crisis of the mid-1880s.

<><><><><><><><><><><><>

Historians have long recognized the quickening pace of structural change within the French labor force in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Machinery challenged handicraft production; international competition compelled managers to reorganize and intensify work routines.[63] One further force creating a "proletariat" in France was the curtailment of temporary migrations to urban industry from the country-side. Industrial workers settled in cities.[64] The stokers participated in the last pattern of change, which entailed far more than taking up new residences. It called into question all the ways the stokers had heretofore related to their employer.

Ceasing to be rural laborers who sought winter work with the PGC was one aspect of a broader alteration in the stokers' independent status. They became dependent on the firm for year-round employment. No longer were they workers who put together a livelihood through varied tasks, among them stoking; they became gas workers, pure and simple. By the 1890s, 45 percent stayed in the distillation room during the summer. Most of the rest struggled for the now coveted "privilege" of having year-round work with the PGC and took jobs as common laborers in the courtyards to be on hand when stoking jobs became plentiful in the fall. Superinten-

[62] For the internal labor market, see chapter 4. For a fine example of a factory manager spoiled by fortunate circumstances, see AE V 8 O , no. 749, report of superintendent of Passy to Arson, April 6, 1869.

[63] Jean-Marie Mayeur, Les Débuts de la III République (Paris, 1973), pp. 66-72; Michelle Perrot, "The Three Ages of Industrial Discipline in Nineteenth-Century France," in Consciousness and Class Experience in Nineteenth-Century Europe , ed. John Merriman (New York, 1980), pp. 149-168.

[64] Lequin, Ouvriers de la région lyonnaise , 1:123-156; Noiriel, Ouvriers dans la société française, p. 83.

dents were now pleased with the number of job seekers available. Indeed, the assistant head of the factory division maintained that some of those applicants took the trouble to procure letters of recommendation from influential people.[65] The sources of this transformation into dependent workers were manifold. Some causes reached back into the deep provinces where the stokers had originated. The heavy rural exodus from Brittany, Auvergne, and Savoy, after centuries of overpopulation and temporary migration, affected the fate of the stokers. The decline of rural industry, the reconstitution of larger farms in response to more commercialized agriculture, and the broadening of peasants' cultural horizons sent thousands of rural hands to Paris and the other metropolises, where they remained permanently.[66] Like the stonemasons who began to settle in Paris some decades earlier, stokers no longer considered returning home. The demo-graphic shifts assured a plentiful work force for the PGC, all the more so because of two crucial changes in Paris.

The local changes undermined the stokers' independence by calling into question their ties to the construction industry as an alternative to the PGC. First, the wages of stokers pulled decisively ahead of building workers by 1880 at the latest. Pay for skilled masons stagnated at around eight francs a day through the rest of the nineteenth century.[67] In the meantime, stokers had taken advantage of the PGC's critical labor short-age in 1880 to strike and win a pay rate of three francs per thousand kilo-grams of coal distilled. That rate assured them a daily wage of almost nine francs and eventually more. Even if stokers were willing to settle for the lower pay of construction workers, jobs would not have been easy to find. The golden era of building had passed by that time. The Parisian housing market was in recession after 1882: Paris had too many apartments, and rents stabilized until the century ended.[68] Baron Haussmann's projects had once made it possible for stokers to escape their painful work for part of the year; alternatives to stoking now became much more problematical. Stokers were likely to remain in gas production as long as the company needed them or as long as their stamina allowed. It is not surprising that when two stokers were fired in 1895 for having ruined a retort through

[65] AP, V 8 O , no. 162, report of Euchène to director, April 10, 1906; no. 163, report of superintendent of Ivry plant to Euchène, March 23, 1902; no. 148, "Re-vendications. Service des usines," responses of Gigot.

[66] Françoise Raison-Jourde, La Colonie auoergnate ti Paris au XIX siècle (Paris, 1976), pp. 179-190; Maurice Agulhon et al., Histoire de la France rurale, vol. 3, Apogee et crise de la civilisation paysanne , 1789-1914 (Paris, 1976), pp. 469-487.

[67] Rougerie, "Remarques sur l'histoire des salaires," p. 99-100.

[68] Michel Lescure, Les Sociétés immobiliéres en France au XIX siècle (Paris, 1980), p. 78.

Table 20. Stokers' Years of Work with the PGC | ||

1878 | 1888-1889 | |

Seniority | No. | % | No. | % |

<1 | 25 | 12.0 | 13 | 2.9 |

1-3 | 67 | 32.1 | 78 | 17.7 |

4-5 | 23 | 11.0 | 91 | 20.6 |

6-10 | 39 | 18.7 | 152 | 34.5 |

11-15 | 27 | 12.9 | 72 | 16.3 |

15+ | 28 | 13.4 | 35 | 7.9 |

Total | 209 | 100.1 | 441 | 99.9 |

Sources: AP, V 8 O1 , nos. 1290, 1293. | ||||

negligence, their immediate concern was whether the superintendent would take them back next year.[69]

The consequences of the stokers' dependency were soon visible in pat-terns of labor turnover (table 20). The changes after just a few years of the new conditions were quite dramatic. The portion of stokers who had remained with the PGC three years or less dropped by more than half. More stokers were staying on the job longer. The figures also attest to a reduction in purely seasonal employment. That is why the portion of stokers who lasted fifteen years was actually a good deal higher in 1878 than in 1888; men who stoked year round could not have lasted so long. Most would have been incapacitated after a decade of year-round work.

Another consequence of dependence on the PGC was an end to the paradoxical shortage of stokers during the slow season. Plant superintendents confidently reported having a surfeit of applicants during the 1890s.[70] Though stokers had once hastened to return to the countryside or snatch a good construction job when the warm weather approached, those options were no longer attractive or available. After 1880 stokers maneuvered to avoid seasonal layoffs. Indeed, the PGC's policies regarding layoffs now became a major source of grievance and frustration.

Not surprisingly, the issue surfaced first in the mid-1880s, when the stokers' dependency became manifest. The PGC had granted a large wage increase to stokers on the occasion of a strike in 1880 and then attempted

[69] AP, V 8 O , no. 150, report of Hadamar, July 10, 1895.

[70] Ibid., no. 148, report of Gigot to director, October 8, 1892. The assistant head of the factory division asserted that each factory received about forty applications a day.

to reduce its wage bill by hiring Belgians and Italians at lower pay. By 1887 more than 40 percent of the stokers at the La Villette plant, the company's largest, were foreigners.[71] French stokers complained that the foreigners were retained at the plant during the slow season whereas they were sent away and then not always rehired in the fall. Pressured by the city and by the national administration to favor French workers, the company announced a formal policy of layoffs based on seniority. The concession settled very little, however, for the PGC altered its interpretation in a mercurial manner and never clarified it in detail. Was seniority determined on a plant-by-plant basis, or was it companywide? Did a stoker who worked two full years have more or less seniority than a stoker who had returned for five consecutive winter seasons? The director allowed plant superintendents to apply the rules as they wished and to improvise. He undoubtedly did not mind that arbitrary layoff procedures sowed dissention among stokers even as they darkened relations with the company.[72]

The shift to dependency brought prominence to the distinction between stokers with the newly acquired right to work all year and those subject to layoffs. Superintendents reported that at least three years of employment with the company were necessary to establish that right, and the slow expansion of gas consumption in the 1890s must have lengthened that term. In the meantime, misunderstandings over rules were numerous, and fights among stokers, each defending his rights, broke out.[73] The solidarities promoted by common frustration with the company were partially eroded by jealousies among stokers over the issue. That these tensions could cut deep is demonstrated by the aftermath of the wildcat strike of March 1899 (see chapter 4). The company it will be recalled, agreed to take back all strikers, but it was necessary to put them to work in plants other than the ones in which they had been employed. The stokers already at those plants protested the strikers' presence as a threat to their own layoff status. Thus, comrades-in-arms one day became squabbling job seekers the next.[74] The irony was that the March strike had been triggered by a foreman's arbitrary application of rules on layoffs. The quest for se-cure, year-round work had come to color relations among workers and relations between workers and the PGC in ways it could not have during the 1860s.

[71] Ibid., no. 90, letter of Camus to consul general, October 1, 1887.

[72] Ibid., no. 151, "Règlement à l'ancienneté pour toutes les catégories"; letter of Lajarrigue to Hadamar, November 8, 1901; Le Journal du gaz. Organe officiel de la chambre syndicale des travailleurs du gaz, no. 108 (June 5, 1897): 2.

[73] AP, V 8 O , no. 163, report of superintendent of Ivry plant to Euchène, March 23, 1902; no. 151, letter of Lajarrigue to Hadamar, November 8, 1901.

[74] Ibid., no. 159, report of Gigot, March 25, 1899.

The dependent status of stokers had not yet solidified by 1880, but al-ready the strike of that year was different from earlier ones because of the change. The defiant stokers sent a delegation to management, not to announce a collective departure for construction sites, but rather to make specific demands regarding their situation at the PGC. Moreover, stokers were now determined to profit from their higher productivity to a greater extent than earlier. They pushed managers to accept piece-rate pay, which the engineers had been postponing for a decade.[75] Still another novel element of the stokers' strike was the nonwage grievance. To restore labor peace, the company took its first step to lighten stokers' burdens. It agreed to hire workers to carry coal from the yards to the distillation hall and to break the coal into small pieces suitable for charging. Eventually management would turn this concession to its own advantage by converting the new crew into a cadre of potential replacements for stokers, but initially it was a benefit stokers won through collective action.[76] The strike of 1880 was a relatively minor outburst—quickly settled because the company had no choice except to yield—but it did portend a reshaping of the stokers' protests.

In the end, the stokers' new status owed very little to the PGC's conscious labor policies. Management had long resisted the demand for piece rates in 1880 that eventually drove stokers' wages decisively above those in competing lines of work. The company had never offered benefits, like housing or pensions, that might have made workers cut their ties with rural life or with alternate urban jobs. Dependency came about, as we have seen, through the operation of impersonal forces. Nonetheless, the new status of labor did offer the PGC important strategic tools for dealing with its most obstreperous workers, and the company was not slow to exploit them.[77]

It would be a serious mistake to confound dependency with submissive-ness. To the contrary, dependency eventually forced on stokers a new and potentially explosive set of issues that would create confrontation with the firm. The previous independent situation of stokers had reconciled their interests with the business calculations—though not the moral sensibili-

[75] Ibid., no. 716, "Rapport sur les primes," no. 66, March 1880; Préfecture, B/a 176, reports of March 15-20, 1880.

[76] AP, V 8 O , no. 151, "Communications faites à la presse parisienne"; no. 695, deliberations of June 8, 1899. It should not come as a surprise that the PGC took the step of creating a pool of potential replacements for stokers when labor tensions heightened in 1899.

[77] By contrast, David Brody, Steelworkers in America , pp. 74-102, depicts the classic example of the United States Steel Corporation explicitly encouraging de-pendent status among its skilled workers.

ties—of management. Under these conditions Calhoun's model for skilled industrial workers approximated reality. But as we shall see in chapter 8, dependency brought an end to these circumstances. A brief comparison of strikes of the 1860s with those of 1890 and 1899 illustrates the changes in protest that were about to ensue. In 1890 the stokers' work stoppage won them a raise, but they still defined the outcome as a failure. In 1899 their strike demands allowed for a sharp reduction in pay. In effect, dependency gave stokers a set of demands that were more, not less, difficult for the company to satisfy. The stokers started to behave more like craftsmen, conscious of control over the workplace, than anyone would have hereto-fore imagined possible.[78]

The Common Laborers

The multifarious business activities of the PGC created a demand for general laborers to perform a wide variety of simple tasks. Unlike stoking, these jobs could be mastered quickly and most any worker could do them. Taken together, the many sorts of common hands comprised a corps more than three times as large as the stokers. Wage earners of this kind have not had much of a presence in labor history owing to their silence. By and large they accepted the conditions offered them, either because it was the best they could hope for or because they were powerless to do otherwise. One of the noteworthy features of industrial relations within the PGC was that the common laborers acquired their own voice, for a time a clearer one than that of their comrades with market power.

With the company recognizing sixty-seven categories of unskilled workers, the diversity defies easy categorization.[79] Whatever grounds these laborers had for collective action did not derive from common work conditions. A large group of unskilled laborers was composed of coke handlers—nearly 850 of them in 1890 (table 21). These workmen took the extinguished coke from the stokers and processed it for residential use. This task involved piling the coke in large heaps, filling burlap bags with it, carrying the bags on their backs to delivery wagons, and loading the wagons. Obviously, there was nothing intricate about such work, but it was exceptionally taxing. The PGC did not begin to mechanize these op-

[78] For confirmation of this tendency among skilled workers of modern industry, see Reid, Miners of Decazeville , pp. 130-139; Margot Stein, "Working to Rule: The Social Origins of a Labor Elite. Engine Drivers, 1837-1917" (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1977), pp. 246, 278-292.

[79] AP, V 8 O , no. 159, report of Bodin to Euchène, March 3, 1899.

Table 21. Common Laborers at the PGC, 1889-1890 | |||

Category | Approximate No. | Daily Pay (francs) | |

Distillation plants | |||

Coal handlersa | 400 | 5.00 | |

Purification workers | 150 | 4.50 | |

Courtyard workers | 680 | 4.00 | |

Others | 60 | 4.50 | |

By-products plants | |||

Machine operators | 70 | 4.25 | |

Laborers | 120 | 3.75 | |

Coke service | |||

Coke handlers | 850 | 3.75 | |

Carters | 290 | 4.50 | |

Lighting service | |||

Lamplightersb | 1,050 | 2.40 | |

Greasemen, waxers, repairmenc | 275 | 3.75 | |

Ditch diggers | 180 | 3.50 | |

Total | 4,125 | ||

Sources: AP, V 8 O1 , nos. 148, 149. | |||

a These laborers were supposed to be capable of replacing stokers on a temporary basis. | |||

b Lamplighters were paid 65, 70, or 75 francs a month, depending on seniority. cGreasemen were paid 1,200-1,400 francs a year. | |||

erations until the last years of the century. By the company's own estimates a coke handler carried each day 186 sacks weighing (altogether) eight thousand kilograms for a total of thirteen kilometers.[80] This toil brought the handlers a meager wage of 3.75 francs a day in 1890. The ten-hour day was often extended by the irregular arrivals and departures of the delivery carts.

Nearly three hundred coke deliverymen completed the labor force attached to this department. They formed a highly problematical service. Every year the company had a dozen or so prosecuted for theft or fraud. At one point the PGC hired undercover agents to spy on the delivery carts as they made their rounds but finally decided that the expense of such surveillance was too great and that it was easier to rely on customers' complaints to detect fraud. The record of criminality gives substance to the assertion made by the chief of the coke department that the company

[80] Ibid., no. 148, "Examen des réclamations concernant le service des cokes (4 avril 1892)."

paid too poorly to attract carters of higher integrity.[81] For their part, carters had their own grievances against the firm. They bore civil and criminal responsibility for any accidents they may have caused on the crowded streets. A majority of carters affirmed their willingness to contribute two francs a month from their meager pay for a mutual insurance fund, but the company refused to help them organize one. Moreover, management forced high standards of punctuality on these workers, who were accustomed to the more casual schedules characteristic of outdoor workers. If one was five minutes late for the 5:00 A.M. call, the company assigned his wagon to another worker, and he lost a day's pay.[82]

Almost seven hundred common laborers worked in the courtyards of the distillation plants. Their jobs included unloading shipments of coal, packing by-products, and performing general maintenance chores. The company made an important distinction between the few courtyard men who could replace absent stokers and those who could not. It attempted to retain as many of the former as possible by paying them an extra fifty centimes a day.[83]

In close proximity to the courtyard workers were the two hundred or so who operated the by-products plant. Their jobs were particularly unpleasant because of the stench or fumes from the chemicals they worked with. Some had to stand all day knee deep in pools of noxious liquids. Others operated the machinery or fueled the furnaces. Eye ailments and skin rashes were common occupational hazards for these laborers. Despite these hardships, the by-products workers were among the poorest paid in the company.[84]

Another large group worked not in production but in the distribution service, as lamplighters, greasemen, waxmen, and repairmen. Because their labor was fixed, regular, and predictable, the company commissioned them after a probationary period. The thousand or so lamplighters came closest to thinking of themselves as quasi-municipal workmen: part of their pay came from a municipal subsidy (three centimes per streetlight per day), and their labor was directly related to a public service. The municipal council could alter their work routine by changing its regulations

[81] Ibid., no. 90, report of Hallopeau to director, January 14, 1867. The deliberations of the comité d'exéution contain a large number of decisions to prosecute carters for theft or fraud.

[82] Ibid., no. 148, "Revendications. Service des cokes (17 septembre 1892)"; re-port of Montserrat, December 23, 1891; report of Montserrat, April 27, 1892.

[83] Ibid., no. 151, "Revendications générales—personnei ouvrier."

[84] Ibid., no. 157, "Conditions du travail et d'hygiène des ouvriers des anthracènes"; "Procès-verbaux de la commission administrative de la Caisse de prévoy-ance," deliberations of March 11, 1864.

concerning street lighting. The PGC regarded its lamplighters as part-time laborers. It contended that the rounds of lighting, cleaning, and extinguishing the sixty-five or so assigned streedamps required at most five hours a day. It noted that the majority of the lighters had secondary occupations, as concierges, street peddlers, shoemakers. The lighters them-selves asserted that their work demanded an eight-hour day. At one point the company had a spy follow a union leader on his rounds and found that the tasks did indeed require eight hours—but only because of frequent stops in pubs or other breaks. The lamplighters, maintaining a preindustrial conception of their work routine, did not wish to define these breaks as external to the job.[85] In any case, the lighters' secondary occupations gave them some independence from the company and they used it to be among the most turbulent of unskilled laborers.

The greasemen, waxers, and repairmen had an advantage that most wage earners would have welcomed. As "fixed workers," they were paid by the month, and their employment was permanent. Their pay was very low, however, twelve hundred to fourteen hundred francs a year The manual workers put in thirteen-hour days, outside, painfully exposed to the elements.[86]

There were another two hundred workmen who practiced a trade— plumbers, wheelwrights, fitters, turners, and others. These laborers were not easily categorized. They were not affiliated with the Parisian crafts. Perhaps because their jobs were ancillary to the PGC's central production concerns, the tradesmen were never able to take a directing role in any protest. There was nothing about their comportment that exemplified the proud, contentious craftsmen. For the most part their fate was more closely linked to the common hands than to the stokers.[87]

In important ways the differences between stokers and common laborers was artificial, or at least superficial. Bargaining power on the job was one of the few social distinctions between stokers and common hands. The social background of the two groups could not have been more similar. Both participated in the temporary rural immigration to the capital as long as it lasted. The rural exodus from the deep provinces supplied an

[85] Ibid., no. 151, report of Saum to director, June 3, 1893; reports of Saum to director, April 2, 14, and 17, 1892; "Revendications des allumeurs"; "Renseignements sur les professions des allumeurs (24 mars 1900)." In 1900, 846 of 1,028 lamplighters were reported to have second occupations.

[86] Ibid., no. 148, "Syndicat. Service extérieur."

[87] Mechanics who worked for the company making motors, stoves, and valves did so at piece rates under sweated conditions. They were the sort of degraded hand-workers that fully trained mechanics called "small hands." See ibid., no. 151, re-port of Maubert, August 25, 1897.

increasing portion of both sorts of gas workers. Most stokers had roots in both camps. The company recruited them among the common hands; the stokers spent summers in the courtyards, working as general laborers. Stokers eventually returned to unskilled labor when they could no longer endure the work.[88] In a sense, stoking was not much more than a stage in the life cycle for the minority of physically qualified common laborers.

Nonetheless, the common laborers had a distinctive set of problems on the job—above all, being caught in the internal labor market that managers created for them.[89] That situation meant, as we have seen, low and uneven pay. Table 21 must be read in this context. As a result of the step system of pay which the company imposed on them, a third to a half of each category earned twenty-five centimes less than the average par and a like portion earned twenty-five centimes more. Managers hoped to impart moral lessons as well as divide workers through segmented pay, and they probably achieved the second goal. In 1892 a union delegate from the coke department admitted that "young and older workers do the same job at different pay and there results an antagonism between the two ."[90] Unlike stokers, the common hands could not mount a successful offensive against unequal pay for equal work.

When, after 1890, convincing the public that its pay scales were generous became important to the PGC, it could do so by publicizing the stokers' rates alone, even then neglecting to mention the seasonal quality of the pay. Average wages of common hands were less than half of the stokers' in 1889. The comparative data that engineers gathered from neigh-boring firms showed that the PGC's compensations were in line with the lowest-paying industries—fertilizer, animal-rendering, and glue companies. Engineer Audouin, who led the fact-gathering mission, was surprised to learn that the Lebaudy and Sommier sugar refineries, notorious exploiters of Italian and Belgian labor, paid the unskilled as well as the PGC. Refinery workers were hired at 3.75 francs a day and could earn 4.50 to 5.50 francs with experience.[91] A clearer understanding of market wages came as something of a revelation to the PGC's managers. Up to this point they had hoped to be able to ignore the market. Whether the new aware-ness undermined their self-righteousness about labor policies is doubtful. The low pay that the gas company offered inevitably generated a rapid

[88] Ibid., no. 163, "Assimilation des ouvriers (4 février 1903)."

[89] On the efforts to create an internal labor market, see chapter 4.

[90] AP, V 8 O , no. 148, "Procès-verbaux de la quatrième audience donnée le 3 mars 1892 aux délégués" (remarks of Gabanon).

[91] Ibid., "Renseignements sur les salaires journaliers des ouvriers pris chez différ-ents fabricants."

turnover of the labor force. After all, common hands could earn more elsewhere, suffer no less from seasonal layoffs, and often have tasks that were less painful. Even the greasemen, who were commissioned, had a resignation rate of 7 percent in a year of recession, like 1889, and 19 per-cent in a year of dramatic labor shortages, like 1881.[92] Wage earners, how-ever, were by no means committed to a peripatetic existence by preference or by life-style. Michelle Perrot has correctly identified an "aspiration for rootedness and for security of employment and retirement" among common hands, and it is dear that an appreciable portion of those at the PGC sought those arrangements.[93] They became possible when political pressures and bourgeois reform altered the wage policies of the firm. Average pay rose 16 percent, to 5.63 francs, by 1895, not counting the profit-sharing bonus introduced in 1893 (30-38 centimes a day).[94] Furthermore, the small pensions of 360-600 francs promised by the company in 1893 made employment more attractive.[95] Such remuneration still did not attain the level of largesse the PGC publically proclaimed, but the unskilled nonetheless seized on the improvements to construct an element of stability in their own lives. Twenty-nine percent of the ditchdiggers in the distribution department, 36 percent of the workers in the mechanical shops, and 54 percent of the chemical-products laborers accumulated at least ten years of seniority by the end of the century. Despite the grueling routine in the coke department, 52 percent of the laborers stayed on the job at least ten years.[96] One greaseman aptly expressed the new outlook on the PGC as employer. Admitting to having committed a serious error on the job, he begged the director to inflict no more than a long suspension. "Being fired—that would be death" he lamented.[97] General laborers seemed eager to define themselves as the personnel of one firm and make long-term commitments to it as soon as competitive pay made that situation viable. Like stokers, common hands came to depend on the PGC for steady employment.

The intervention of the city of Paris in the labor affairs of the gas com-

[92] Ibid., no. 148, report of Perrin to director, December 24, 1881; no. 90, report of Arson to director, January 11, 1889. Up to 1890 the PGC seemed to hire roughly fifteen hundred new workers a year.

[93] Michelle Perrot, "Une Naissance difficile: la formation de la classe ouvrière lyonnaise," Annales : Economies, sociétés, civilisations 33 (1978): 834-835.

[94] AP, V 8 O , no. 148, "Etat comparatif des salaires."

[95] So eager were wage earners for the benefits of a pension that they offered to contribute to the pension fund through a withholding of pay. See ibid., no. 155, "Règlement relatif aux versements à effectuer par le personnel ouvrier (1892)."

[96] Ibid., no. 151, "Personnel des ouvriers'; "Ouvriers des travaux chimiques"; no. 156, "Augmentation des salaires depuis 1 mai 1890."

[97] Ibid., no. 162, letter of Le Blais to director, n.d.

pany ended a prolonged period of helplessness. The unskilled may have admired the ability of the stokers to force wage concessions on management, but they had rarely been able to duplicate the success. Hence the earnings gap between the two sorts of laborers widened continuously. When the company was founded, general laborers received two-thirds of the stokers' daily pay; by 1890 the former received less than half.[98] Only in the very few years of exceptional labor shortages in the capital did the unskilled acquire the bargaining power that the company could not easily resist. Common hands found such power only in 1867, 1876, and 1881. Otherwise, the few job actions that occurred ended in repression.[99]

The lamplighters were the most aggressive of the general laborers. The second jobs that they held gave them some independence; furthermore, they knew that the disruption of public lighting even for a brief time would create public ire against their parsimonious employer. These advantages, real though they were, profited lamplighters not at all in 1865. Inspired by a successful strike among coach drivers, lighters demanded a raise from 65 francs to 90 francs a month and threatened to desert their rounds if it was not conceded. This threat made managers organize one of their acts of "salutary intimidation." They created a substitute corps of lighters, composed of inspectors, greasers, and auxiliary lighters (those still in the midst of their probationary periods). On the day before the threatened strike the director sent the substitutes to meet the regular workers with letters of dismissal. Eventually the company took back most of them, excluding only the perceived agitators. The rehired lighters had to accept a loss of their seniority in step pay and of their annual bonuses. If the potential strikers of the 1860s expected the municipal council to plead for leniency on their behalf, they received no support whatsoever from that quarter.[100] The exquisite stagecraft choreographed by the com-pany in response to the strike threat told unskilled laborers that they could expect neither success nor clemency.

Even the modest wage gains that laborers were able to win during the boom of 1876-1882 came at a price. The PGC soon compensated for the raise by hiring foreign workers in large numbers. The result was new ten-