Bibliothèque Royale, Ms. 9249–50

The minute contains 112 leaves, 41 × 28.5 cm., with a text block of 29 × 19 cm., of twenty-two lines, on a fine sturdy paper.[5] It is handsomely encased in a modern binding of burgundy red leather, quarter-bound, with oak boards, and clasps in heavy brass.

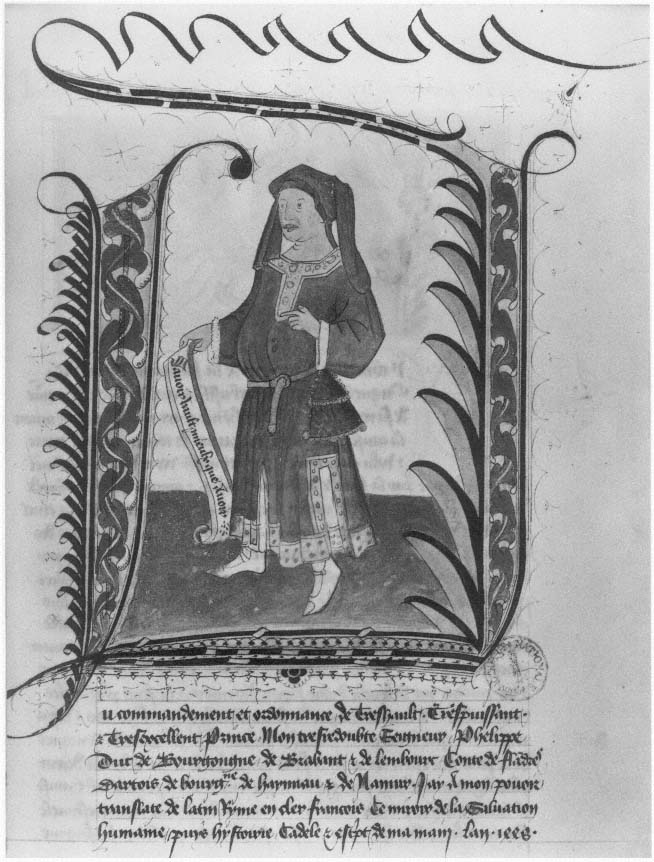

The first page displays a giant decorated M with a face on both sides, suggesting a mirror, over the letters I N U T E, each in a different style of capital (Plate III-3). The title page, on the verso (Plate III-4), is a full-page illuminated letter with a winged dragon forming an initial S above the calligraphed "Ensieut le miroir de la saluation humaine" (Here follows the mirror of human salvation). On the next recto Miélot describes the commission (fig. III-1). A large D encloses a modest self-portrait of the pot-bellied translator in a bejewelled robe. Miélot holds a banderole inscribed with the motto "Savoir Vault mieulx que Avoir" (To know is worth more than to have). Beneath is his text, translated as follows:

At the command and order of the very high, very powerful, very excellent prince, my most honorable lord Philip, Duke of Burgundy, of Brabant and of Limburg, Count of Flanders, of Artois, of Burgundy, of Hainaut and of Namur, I have to the best of my ability translated from rhymed Latin into clear French The Mirror of Human Salvation , then pictured, ornamented, decorated and written it in my hand. The year 1448.

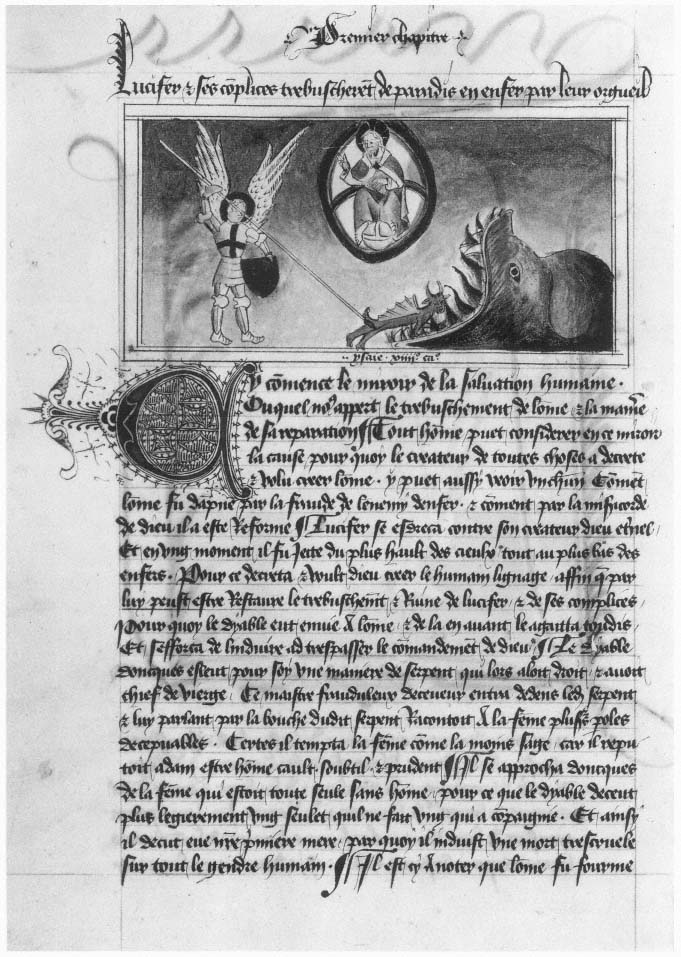

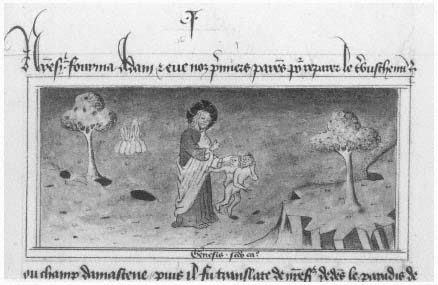

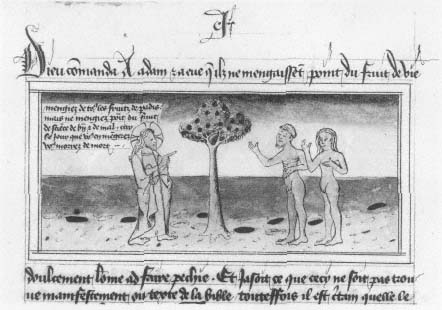

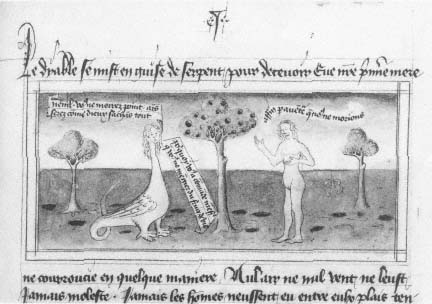

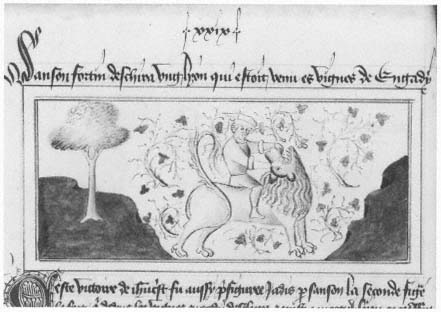

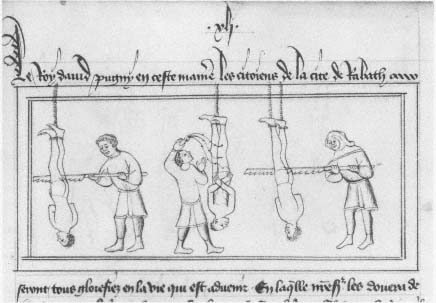

The text of the Speculum translation begins on folio 2 verso, below a miniature, and is written across the page in a single column (fig. III-2). The caption above the miniature explains the subject, the fall of Lucifer and his accomplices from Paradise into Hell because of their pride. The picture appears to be finished. Lucifer's accomplices are not depicted, God is seated in a mandorla in the heavens, and Lucifer is shown as a winged bull being prodded into the mouth of Hell by an armored angel. This miniature was probably not made by Miélot although he might have copied it from the Latin manuscript he was translating. The illustrations near the beginning have the base coat of paint (figs. III-3-a, b, c, and 4-a) but are unfinished. Later in the minute they are line drawings (figs. III-4-b and c). Beneath the first two are written the chapter and verse of the Bible to which the text and illustration refer, but this is not continued beyond Chapter I. Miélot was a good decorator, translator, and scribe, but he was not a miniaturist and if these sketches are his, they were intended to show the subjects to the artist.

[5] C. M. Briquet, Les Filigranes , edited by Allan Stevenson (Amsterdam, 1968), watermark 3544.

III-1.

Illuminated D with commission and date, 1448.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine .

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. 9249–50, fol. 2 recto.

III-2.

The Fall of Lucifer.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine , Chapter I.

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. 9249–50, fol. 2 verso.

III-3.

a. The Creation of Eve, fol. 3 recto.

b. The Admonition, fol. 3 verso.

c. The Temptation, fol. 4 recto.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine , Chapter I.

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. 9249–50.

III-4.

a. Samson Rends the Lion Asunder, Chapter XXIX, fol. 59 verso.

b. The Sufferings of the Damned in Hell, Chapter XLI, fol. 82 verso.

c. How King David Punished his Enemies, Chapter XLI, fol. 83 recto.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine .

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. 9249–50.

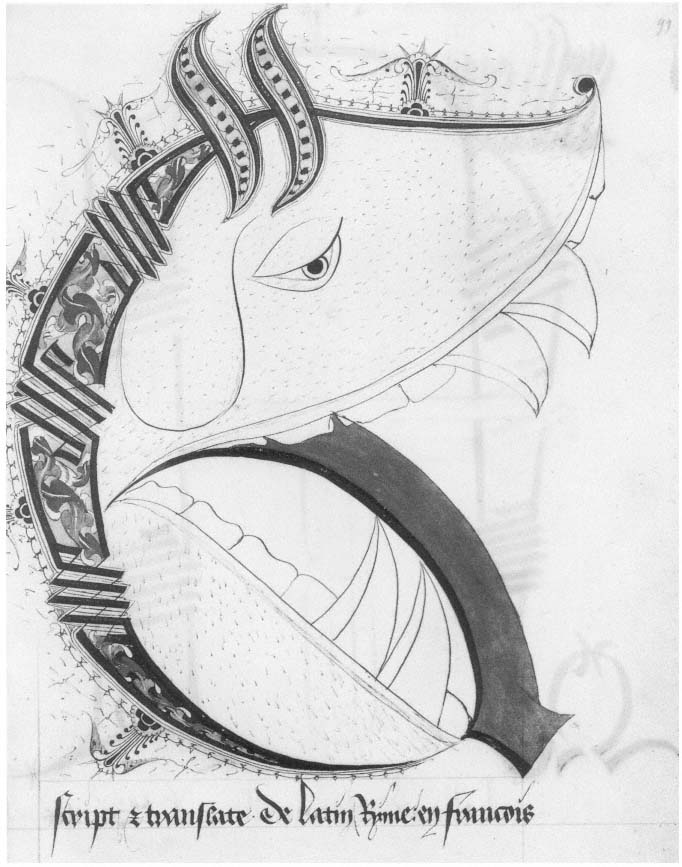

The end of the text of the translation is followed by three full-page decorated, colored and gilded initials, like those at the beginning. Folio 98 verso is a large decorated C enclosing another self-portrait of Miélot above the lettering "y fine le Miroir de la salvation humaine" (fig. III-5). In Middle French the word for "here" was "cy," not "ici." Facing the initial is a letter E in the form of a toothed dragon or sea monster, similar to the one shown as the mouth of Hell (figs. III-2 and 6 ) above the letters "script & translate de Latin Ryme en francois" on 99 recto.

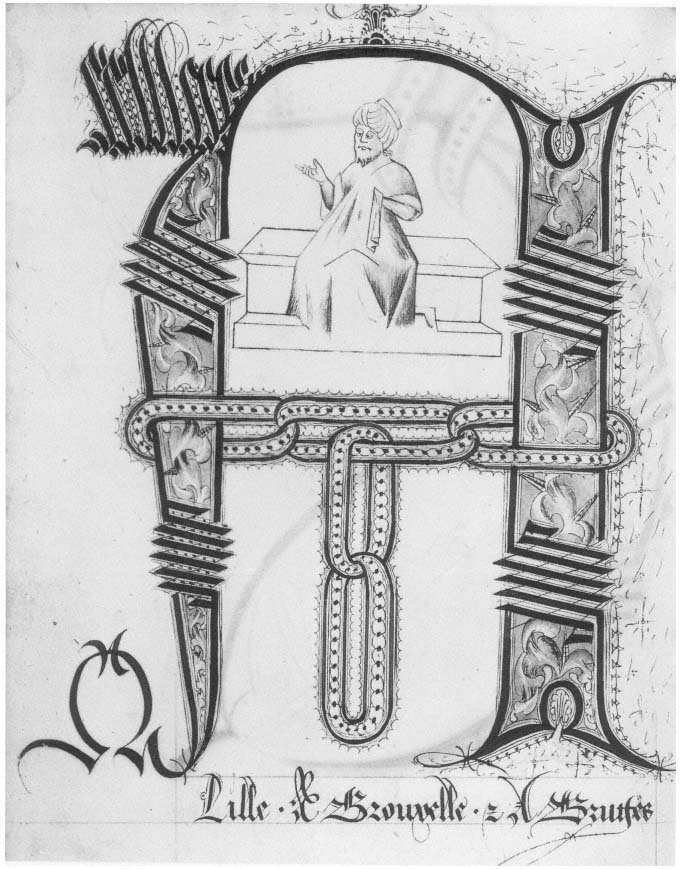

On the verso is an A (for "at") with a crossbar and two hanging links of decorative chain over the words "Lille à Brouxelle et à Bruges" (fig. III-7). The Duke of Burgundy had courts in the three cities, and Miélot must have worked on his translation in the three places. Seated in the letter A, on a coffer, is a robed and turbaned man; possibly the chains refer to the capture of Christians by Moslems in the Holy Land, as Philip's father, Jean the Fearless, had been in the crusade of 1396. Philip is known to have planned a crusade and, in fact, it is recorded that, as a boy, he dressed in Turkish costume and wandered in the grounds of the ducal palace, perhaps plotting the future campaign.[6]

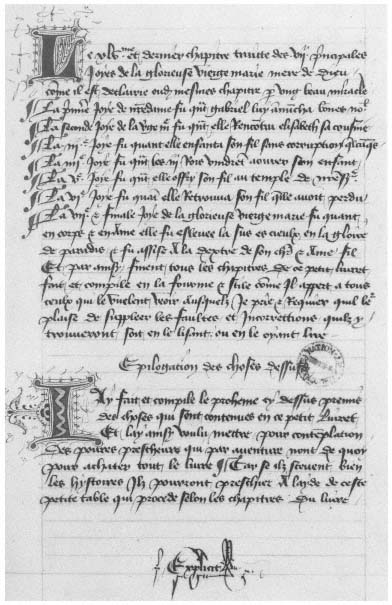

The manuscript ends with a Prohemium (fig. III-8) in which each of the forty-five chapters is summarized, followed by an Explicit entitled Epilogation des choses dessus (Epilogue of the matters above) which states, translated from the French:

I made and compiled the prohemium here above, explaining the things which are contained in this little booklet (ce petit livret). I have wished to do it for the contemplation of poor preachers who by chance do not have the means to buy the complete book. Because the stories are well-presented they will be able to preach with the aid of this little index which proceeds according to the chapters of the book.

Miélot finished his minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine in 1449 and it was in April of that year, probably as a result of the Duke of Burgundy's approval of it, that Miélot was attached to the Ducal court with regular wages. The archives show that the Duke reimbursed him rectroactively for the eighteen months he had worked on Ducal commissions before this, presumably including the preparation of the minute .[7]

In his manuscript of the Debat de noblesse , Miélot refers to himself as "indigne chanoine de St. Pierre de Lille et le moindre des secretaires dicelluy seigneur et prince" (humble canon of St. Pierre of Lille and the least of the secretaries of this lord and prince), but, in fact, he was one of the most educated, talented, and accomplished men in the service of the court, at once copyist, illuminator, historiographer, and translator.[8]

[6] Johanna Hintzen, De Kruistochtplannen van Philip den Goede (Rotterdam, 1918). See also Charles de Terlinden, "Les Origines religieuses et politiques de la Toison d'or," in Publications du Centre Européen d'Etudes Burgondo-Médianes, V (1963), pp. 35–46.

[7] Alexandre de Laborde, Histoire des Ducs de Bourgogne , I (Paris, 1849), p. 400.

[8] J. W. Bradley, A Dictionary of Miniaturists, Illuminators, Calligraphers and Copyists (New York, 1958), p. 324.

III-5.

The first page of Miélot's three-page colophon.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine .

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. 9249–50, fol. 98 verso.

III-6.

The second page of Miélot's colophon.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine .

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. 9249–50, fol. 99 recto.

III-7.

The final page of Miélot's illuminated colophon.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine .

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. 9249–50, fol. 99 verso.

III-8.

The Explicit of the Prohemium.

Minute for Le Miroir de la Salvation humaine .

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels,

Ms. 9249–50, fol. 112 recto.

We find from the Explicit of the Traité de vieillesse et de jeunesse which he wrote at Lille in 1468, dedicated to Louis of Luxembourg, that he was born in a village in the bishopric of Amiens.[9] Nothing is known of his early life, but his education, both secular and religious, must have been thorough, for, in the archives of the church of St. Pierre at Lille, Miélot was entered as a Canon from 1453 to 1472. He was probably not required to remain in residence, but he exercised his canonical functions properly.[10] He was concurrently in the service of Philip the Good until the latter's death in 1467. Records show that he worked afterward for Louis of Luxembourg, Count of St. Pol, as well as for Charles the Bold, Philip's son and successor.[11]

[9] Lutz and Perdrizet, Speculum Humanæ Salvationis (Leipzig, 1907) Vol. I, p. 107.

[10] Ibid. , p. 108.

[11] Bradley, op.cit. , p. 325.