"We're Not Working":

The Strike Begins

Although the Filipinos had issued a strike statement, they had not made any strike preparations. They did not even have a fund to cover food expenses for striking laborers. Since no Filipinos in the islands were successful enough to give financial help to the strikers, they sought aid from the Japanese Chamber of Commerce of Honolulu, which rebuffed them. On the evening of January 17 Manlapit issued an order to postpone the strike planned for January 19, stating that he had failed to get assurances of cooperation from the Federation of Japanese Labor of Hawaii. But on January 19 Terasaki noted in his diary, "Filipinos at Ewa, Waipahu, Aiea, Kahuku start their strike. At Ewa Portuguese and Puerto Ricans join in. There may be a total of 3,000 people." Why did the strike start even though it was to have been postponed?

It began when a Hawaiian luna sneered at Filipino laborers at Kahuku Plantation, "No can strike, you, Filipino, hila hila [cowards]." At the close of work on January 18, the agitated workers gathered at the Filipino camp at Kahuku Plantation. Ignoring Manlapit's order, at 6:00 P.M. they made an independent announcement that they were on strike. This action spread immediately to other plantations on Oahu, and all the Filipino laborers left the cane fields the following morning.

Ironically, the Filipino workers had been brought in great numbers to Hawaii as strikebreakers during the first Oahu strike in 1909. They had arrived in Hawaii to control Japanese laborers who were "dangerous and didn't know their place." At the time, the HSPA noted, "The outcome of this strike movement, while calling for great expense to the Planters' Association and the territory, has the promise of proving a blessing in disguise. Too long have the vested interests of the territory permitted the dominating nationality to insidiously dispossess others in the varied lines of higher grade work."[10] Ten years later, however, the Filipinos, now the second-largest labor force after the Japanese, were ready to take on the HSPA with all its power.

Most Filipino laborers were single. About 40 percent had wives and families, whom they had left in the Philippines. Although many looked forward to being reunited with their families, statistics show that only 48 percent actually returned to their homeland. Under these circumstances cockfights and "three-minute dances" were their only fleeting pleasures. They eagerly looked forward to the arrival in camp of dance troupes from the Philippines. For the price of a ticket they could dance

the tango, pressing their bodies against the dancers for three minutes. Some Filipino workers were also said to engage in homosexual activities, and for that reason Japanese immigrants held them in contempt. At festivals and celebrations Filipino workers sometimes danced with each other to the beat of the rumba whose intense rhythm blended the native music of Cuba with the music of the African slaves taken to work in Cuban sugarcane fields.

The example of the Filipino strike that began on January 19 stirred the Japanese laborers but they were slow to take action.

"Japanese cane workers threaten general strike" ran the lead headline in the January 20 Honolulu Advertiser . From the start of the strike the English-language press focused attention on the Japanese. Indeed, they treated the strike by the Filipinos as though it had been instigated by the Japanese. In fact, the Federation of Japanese Labor had announced that if the Filipinos went on strike, "Our position and intentions are wholly legal and orderly. If a strike of Japanese labor shall be called, [the laborers are] cautioned to quit their places in a quiet and peaceable manner." The Japanese plantation workers in Oahu were equally cautious. Flatly refusing to follow the Filipinos, whom they looked down on, they chose to work in the fields even though the Filipinos were on strike.

"Pau hana, no go work "

The Filipino laborers, who had never doubted that the Japanese would stand with them, were enraged. At Waipahu Plantation several dozen Filipinos attacked Japanese workers boarding a train to go to the cane fields on the morning of January 21. The anger of the Filipino workers was so intense that the Filipino Labor Union was hard-pressed to calm them down. The Japanese workers, fearing that the Filipinos were ready to pull out knives at any provocation, returned to their camp houses with their lunch boxes in hand. At Ewa Plantation, six kilometers west of Waipahu, Filipino workers wielding scythes and knives swarmed around a train traveling through the cane fields. The Japanese engineer and the Hawaiian plantation guard fled into the field of tall sugarcane and hid there until the sun went down. A similar incident occurred at Aiea Plantation near Pearl City between Honolulu and Waipahu. Special officers from the Honolulu police force were rushed to these plantations to arrest numerous Filipinos.

Hiroshi Miyazawa, the federation's man in charge of relations with the Filipinos, went to the large Waipahu Plantation for a workers' rally

at noon the same day. Fearing that harm might come to their families, many Japanese workers concluded that things had come to such a pass that they had no choice but to back the Filipinos and to stop work. Noboru Tsutsumi, who had returned from a trip to Maui, and the other directors, who had returned from observation trips to the other islands, met immediately. After hearing reports from the four islands, they decided to issue a work lay-off order to all the plantations on Oahu—Ewa, Aieia, Waialua, Waipahu, Kahuku, Waianae, and Waimanalo.

Even at this stage, the federation's work lay-off order was considered to be quite different from a strike order. Continuing to negotiate with the planters, the federation sent Goto[*] and Miyazawa to the HSPA to give Mead, the HSPA's secretary, a third written demand for wage increases. The two men also requested that they be allowed to attend the regular meeting of the HSPA to explain the laborers' position. Mead turned them down. It was "no use," he said.

The federation's first delegates' meeting, composed of representatives from plantations from all the Hawaiian Islands, was held on January 25 at the Palama Japanese-language school. At about 4:00 P.M. it went into a secret session closed to outsiders under tight security, guarded by directors carrying pistols. At 10:00 A.M. on the morning of January 26 the Federation of Japanese Labor in Hawaii resolved unanimously to "carry out a walkout by the Federation as of February 1" if there was no change in the attitude of the HSPA.

Secretary Noboru Tsutsumi, as representative of the participants, read aloud the resolution. After waiting for the applause to die down, he explained the organization of federation headquarters. He said that the three secretaries, Tsutsumi, Miyazawa, and Goto, would remain in their positions as agreed upon when the federation was established. The meeting also reconfirmed that the strike would be held only on the island of Oahu, with workers on the outer islands raising support funds. They also needed to be prepared to assist in covering the strike expenses of the Filipinos.

On the following day, January 27, the HSPA gave its final response. The planters' association said that it did not recognize the laborers' union or its right to collective bargaining and that it would not respond to "any demands." In response, the usually moderate Nippu jiji printed a large headline, "110,000 comrades, carry out collective duty; we have an obligation to support the laborers who stand on the front lines so that they may be free of anxieties." The Hawaii hochi[*] also showed its

support of the federation's strike resolution in an editorial with the title "A Courageous Struggle."

On January 30, at a noontime rally at Waipahu, the three federation secretaries were in attendance. In response to Miyazawa's speech in English to the Filipinos, Manlapit appealed for unity between the Japanese and the Filipinos. Goto[*] then explained the procedures and cautions to be followed by federation members. Speaking last, Tsutsumi urged the workers on, "We'd like you to settle in and treat this as a five to six month vacation and hang on until your promised wages are paid."[11] To a man, the laborers in their denim overalls rose with a long and vigorous round of applause. Noboru Tsutsumi had become the indispensable man at rallies on every plantation.

At 2:00 P.M. on January 31 an official strike declaration for "realization of wage increase demands" was issued for the plantations on Oahu island. Beginning on the morning of February 1, Japanese and Filipino laborers, who together made up 77 percent of the plantation workforce on Oahu, boycotted the cane fields.

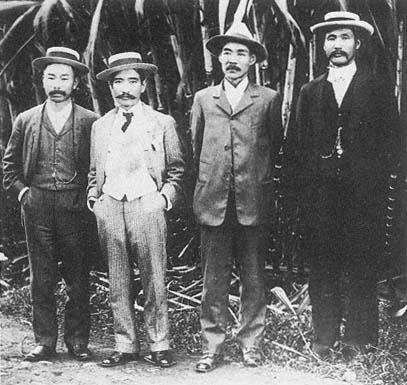

Figure 1

Juzaburo[*] Sakamaki (second from left); Jirokichi Iwasaki (fourth from left).

(Courtesy of Bishop Museum)

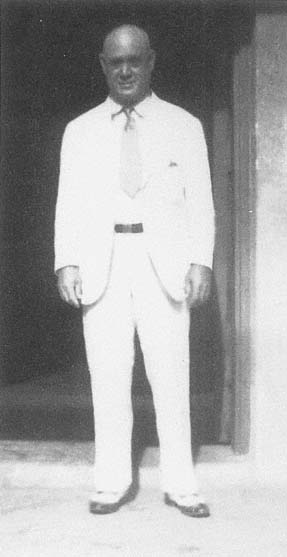

Figure 2

"Fred" Kinzaburo[*] Makino.

(Courtesy of Hawaii hochi[*] sha)

Figure 3

Noboru Tsutsumi.

(Courtesy of Tsutsumi family)

Figure 4

Leaders of the Federation of Japanese Labor. First row: Ichiji Goto[*] (second from left),

Tokuji Baba (third from left), Honji Fujitani (fourth from left), Chuhei[*] Hoshino (sixth from left);

third row: Yasuyuki Mizutari (first on left); fourth row: Shoshichiro[*] Furusho[*] (first on left),

Noburo Tsutsumi (second from left), Hiroshi Miyazawa (fourth from left).

(From Tsutsumi, 1920 Hawaii sato[*] kochi[*] rodo[*] undoshi[*] )

Figure 5

Posters distributed by the Hawaiian planters during the 1920

strike: (top) Filipino strike leader leaving Hawaii with a sack of money;

(middle) striking Japanese worker receiving a pittance from "agitators"

versus worker on the job receiving regular wages; (bottom) cigar-smoking

Federation of Japanese Labor leaders riding in a rented touring car.

(From Tsutsumi, 1920 Hawaii sato[*] kochi[*] rodo[*] undoshi[*] )

Figure 6

Guilty verdict in the Sakamaki dynamiting trial.

(In author's possession)