5—

Failing to See on Contested Ground

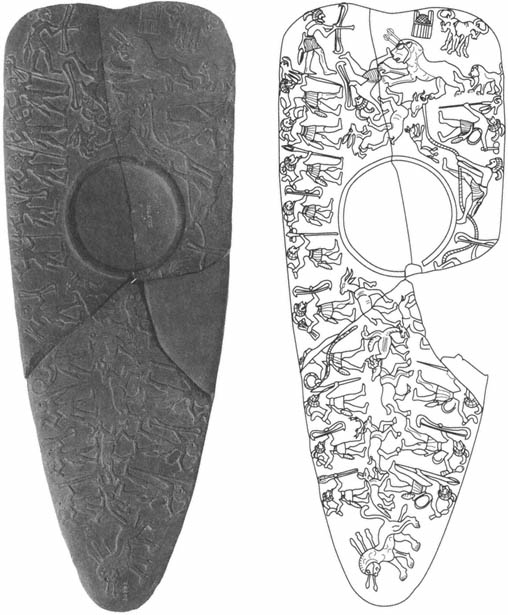

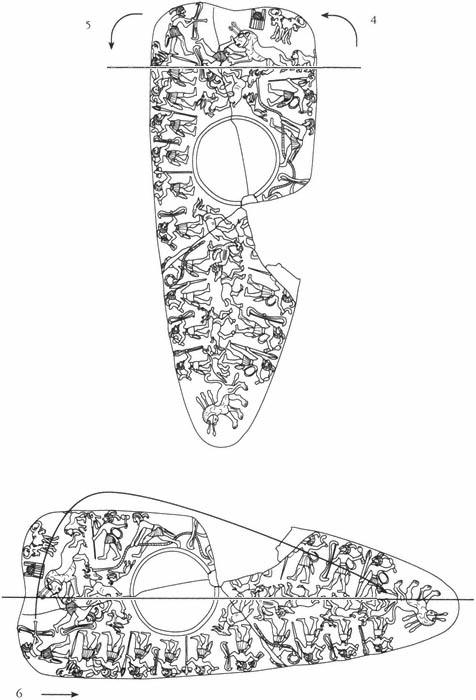

The Hunter's Palette (Fig. 28) was one of the first carved palettes to be discovered. Since it looked substantially different from canonical Egyptian images, it was thought initially to have a Mesopotamian origin. On typological grounds we can reasonably assign it to the Nagada IIc/d or IIIa period, roughly contemporary with the Oxford Palette (Fig. 26). In terms of the history of the chain of replications, however, it makes sense to take it as a later work: its metaphorics seem to require the preexistence of works like the Ostrich and Oxford Palettes.

Two Grounds

The image depicts a group of human hunters, not literally masked but costumed in garb that includes adornments like wild animals' tails hanging from their belts and ostrich feathers in their hair, setting out to hunt desert animals—a deer, an antelope, an ostrich, and so forth (see generally Tefnin 1979 for a penetrating analysis). Several of these creatures appear in ways that might have reminded a viewer of works like the Ostrich and Oxford Palettes (Figs. 25, 26)—for example, an ostrich runs along the ground, lifting its wings before launching into its peculiar hopping flight. The animals all have a distinctive place in the novel metaphorics and narrative of this ingenious image, however, and the hunters themselves are literal representations of the masked human hunters who appear completely outside or only at the edges of the natural world earlier in the chain of replications.

Evidently by stumbling across the den where its young cub resides, the hunters provoke and do battle with a desert lion. On the Oxford Palette two

Fig. 28.

Hunter's Palette: carved schist cosmetic palette, late predynastic (Nagada III).

Photograph courtesy British Museum, London; drawing from Smith 1949.

lions at the top of the reverse attack two gazelles in a scene of nature hunting; the animal-masked hunter observes from the sidelines at the bottom of the same side of the image. On the Hunter's Palette the hunters march from the direction of the bottom of the palette, where they first enter the scene, to the top, where the lion turns away from its expected victims—such as an antelope positioned just below, at right angles to it—to face these human antagonists.

Not masked but rather bedecked in animal finery, the hunters march in two files along the two long, left and right sides of the palette. This arrangement can be seen both as a prototype of the later bands of figures in canonical representation (Figs. 1, 2) and as an echo of the rows of animals on earlier or contemporary decorated knife handles and combs. But there are two important revisions in the new image on the Hunter's Palette. First, whereas the rows of animals depicted in earlier images had been interrupted by anomalous beasts and shadowed by the human presence outside the scene, here the beast, the fierce lion, interrupts rows of human beings depicted within the image. Second, the two long rows of hunters replace the wild dogs announcing the theme and framing the narrative on the Oxford Palette and related works (for example, Fischer 1958; Asselberghs 1961: figs. 129–30, 133–34, 138, 142[?], 170); the wild dogs of the earlier works had masked the hunters who appear here, without masks, in the wild dogs' place. In both of these replicatory revisions, the hunter's mask has been advanced somewhat further into the scene.

The two files of hunters are separated from one another by various other figures. Some of the right-hand hunters carry small round shields, whereas none of the left-hand hunters is so equipped (see Tefnin 1979: 224–25). Both right and left files of hunters carry the same standards, however, which may imply that the groups share a common totem, moiety, or territorial affiliation. Since the minor differences between the two files may be fortuitous, I do not assume that they represent two social groups, however defined, although the finding would not be incompatible with my interpretation, only slightly rewritten. As we will see, the two files do play different parts in the narrative.

Since the hunters surround the lion on all sides, the hunter's place on the encircling outsides or sidelines of nature in the animal-row images conforming to the formulas and on the Ostrich and Oxford Palettes (Figs. 25, 26) has been advanced on the Hunter's Palette literally to enclose nature. The hunters frame

the scene; and in the context of replications like the Oxford Palette, the topmost group of hunter and lion, to be considered in more detail momentarily, can be understood to announce its central theme. Like hunting scenes produced in the later canonical art of the Old Kingdom, several centuries later, where animals are often depicted as driven into fenced enclosures to be hunted for sport by a courtier and his dogs (for example, Vandier 1964: 787–815; Davis 1989: figs. 4.6a, 4.9a, and compare figs. 4.15a–b, 4.16, 4–17a), the files of hunters on the Hunter's Palette could be driving game. No fences are actually depicted in the scene, however, and the figure of a sporting master is not singled out as he would be in canonical hunt scenes; furthermore, the dogs in the central band of the design on the Hunter's Palette are wild rather than domesticated. (Inasmuch as the Hunter's Palette replaces the Oxford Palette hunter, masked by dogs who actually perform the kill, with huntsmen who carry out their own killing with spears, throwsticks, maces, and bows-and-arrows, the hunting mastiffs need no longer be included in the scene of the hunt.) On balance, then, the maker of the Hunter's Palette probably meant to depict a lion and cub surprised in the wild open landscape—indicated by the row of fleeing wild animals pursued by a wild dog—in the course of a hunting expedition rather than the quasi-ritual killing of a previously captured lion and cub in ceremonial combat or sport. Instead of framing an enclosed stretch of ground, the hunters must be advancing through the brush in two files or—depending on how we decipher the composition—trapping animals between two files of men coming together from two directions.

The round-topped building (a "shrine"?) and "double-bull" signs (Fig. 30) at the top right of the image suggest—if we are to take them, like later hieroglyphs, as informational labels or captions—that the entire episode bears some relation to a particular, perhaps sacred building or locality (Vandier 1952: 577–78). The implication is not necessarily that the hunt takes place within this building or locality; instead, the hunters may be affiliated with it, or, among other alternatives, might have dedicated their activities or trophies to it. Another reading could conclude that the signs label the temple to which a palette of this kind was supposedly dedicated. It hardly matters for our general analysis of the narrative structure exactly how we decide these questions. What-

ever their other representational functions might have been, the signs have a role to play in the internal metaphorics and narrative of the image itself.

With the human hunters at the edges of the palette—like the anomalous animals at the ends of rows in the animal-rows formula—the hunt that takes place within nature occupies the central band of space remaining on the palette. In this central passage the scene of nature hunting is presented as less visible than the details around the periphery; it is squeezed between the human hunters and disposed on either side of the cosmetic saucer. Here three jackals are pressed farther into the center of the image from the former place of such scavenging creatures (for example, the wild dogs on the Oxford Palette; see Chapter 4) by the arrival of the human hunters from their former place at the edges of and outside the depicted scene altogether. In keeping with the core formula in which they are often presented, the jackals attack a group of non-carnivores—a wild deer or stag, two antelopes, a gazelle, an ostrich, and a hare—that flee from and either see or fail to see their pursuers. Like the top and bottom and side-by-side zones of the Oxford Palette, the central zone on the Hunter's Palette, containing the scene of nature hunting, is specifically related to the side zones, folding around the top of the image, containing the scene of confrontation between nature and human hunters.

The literal mimesis of nature by the hunters on the Ostrich and Oxford Palettes retreats literally to the sidelines on the Hunter's Palette—to a marginal place in the space or to a former place in the time of the depicted scene; the episode depicted on the Ostrich Palette, the stalking and capture of an ostrich, presumably to acquire its plumes, has clearly already occurred for the hunters on the Hunter's Palette, and the outcome of that episode now appears in their hair. In the central passage of the image, however, the depiction of three jackals and an ostrich taking flight recalls that hunters and animals are intertwined in a continuous cycle of contests, with the hunter's blow (never quite depicted) always decisive.

The animal masks depicted as actually used by the hunters on the Ostrich and Oxford Palettes are removed from the faces of the hunters on the Hunter's Palette. The real site and force of the hunter's blow is advanced into the depicted scene: in their outstretched arms the hunters carry bows, spears, single- or

double-headed maces, and curved throwsticks, and some wear shields or game bags slung over their shoulders. Whatever the symbolic meaning of the insignia (Vandier [1952: 578] and Baumgartel [1960: 98] wish to take them literally, if anachronistically, as territorial emblems of early provinces of Egypt), the standards carried by several of the hunters seem to identify them as heavily armed members of a ruler's retinue. They have evidently marched from their village, as one or more groups, into the wilderness, entering nature not—as the image directly reminds us—for the first time.

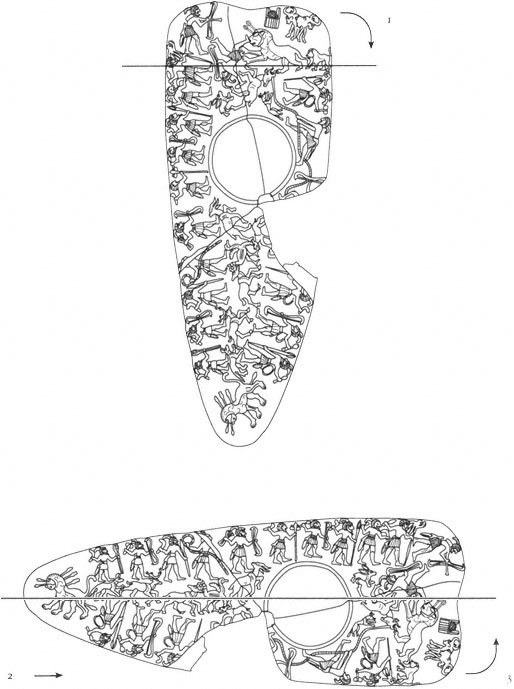

With three exceptions, each figure of a hunter is constructed in the manner that will later become canonical in Egyptian art (see Fig. 2): the head and legs of the human body are displayed in profile, while the torso is displayed frontally. But we should not look at this technique of rendition only in the terms of later standards of canonical representation; instead we should observe that the twisting movement on the Oxford Palette in and through which the presence of the hunter appears there has been brought, on the Hunter's Palette, into the depicted aspect of the hunters' figures. Moreover, the viewer does not flip the palette around itself, as with the Oxford Palette, to understand the rendition of figures and the composition of the scene—but rather turns it on a central pivot.

The canonical construction of the aspect of the human figure, in which component parts of the body are pivoted around a central vertical median (Iversen 1975: 33–37; Davis 1989: 28), can thus be seen as a replication of a certain technique of rendition that serves in late prehistoric image making as a metaphor for the way the hunter's identity is present in or introduced into the natural and the human worlds. Although I do not explore the topic further in this book, the entire pictorial mechanism of late prehistoric representation is advanced into the depicted body of an individual human figure drawn according to the canonical rules of components, proportions, and aspects (Davis 1989: 10–29). In canonical representation, then, the human body becomes the site of late prehistoric metaphors for and narratives of the masking of the ruler's blow. It is for this reason, I suspect, that canonical Egyptian portrayals do not depict the particular physiognomic, ethnic, and sexual characteristics of the individual body, but instead develop stereotypes or symbolic markers for them.

The body of canonical image making is not the physical body, the body with passions, appetites, and desires, but the corporate or social body, the body politic, the body under rule, the body that traces or indexes the order of the state legitimated in its transcendental theodicies—embodying the metaphor for and narrative of the institutions of the hunter's or ruler's mastery of nature (see also Davis 1989: 36–37, 221–24).[1]

Back and Forth, up and down

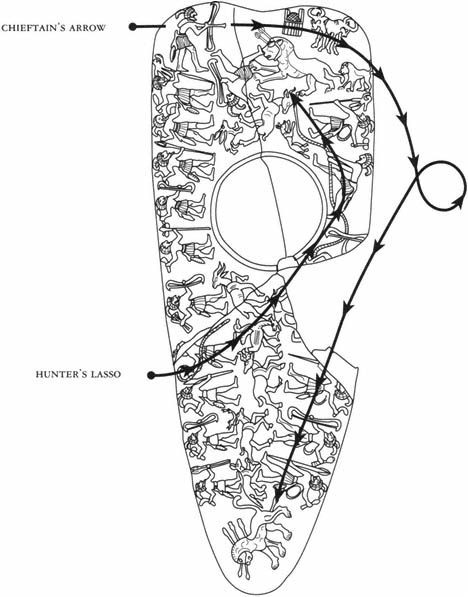

Although the action of the hunt depicted on the Hunter's Palette (Fig. 29) is somewhat obscure, it appears to show the two files of hunters as hunting the noncarnivores being attacked by the three jackals—creatures that disguise the approaching hunters from the other animals, and serve literally, then, as the hunters' forward masks (recalling the jackal-masked human hunter on the Oxford Palette [Fig. 26]). Only one animal, the antelope directly below the cosmetic saucer, sees the human hunters.

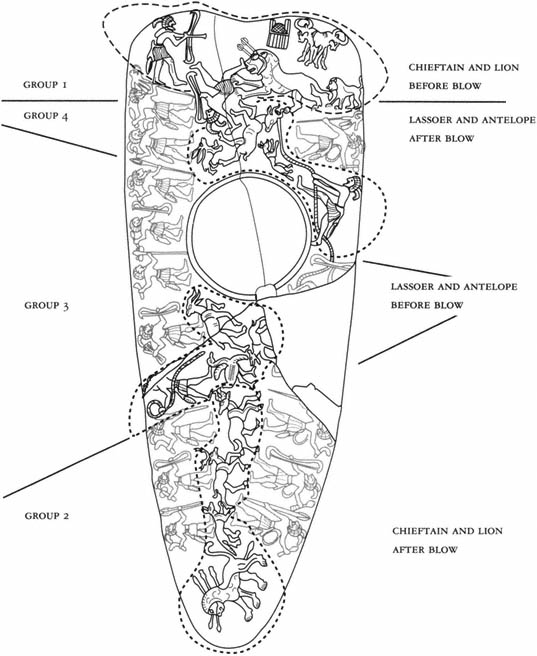

During this action one unfortunate hunter, carrying a bow and a mace, stumbles across the lion cub's hideaway. As is indicated by the position of the cub at the extreme right edge of the scene, the den was apparently across the hunter's line of march rather than in the area, depicted in the central zone, to the hunter's "left." The cub's sire leaps ferociously to defend his offspring and surprises the hunter (see Fig. 29, Group 1). Since there are ten hunters in the left row, a "full complement," and only seven in the right (restoring two in the missing fragment), it would seem that the fallen hunter comes from the shorter, right-hand row. Therefore the lion is breaking into that row from its right—that is, altogether from outside the scene. He is constituted, then, like an anomalous beast entering a row of identical animals or like a carnivore attacking its prey in the basic formulaic images earlier in the chain of replications. From the outside he pounces into the center of the scene. But the hunters, although they are like a row of identical animals in the earlier formula, are not the same as animals; and the lion's fate will be, precisely, that of an anomaly to be suppressed by the order in which the hunters are arrayed and for which they stand. The narrative on the palette unfolds this moral.

Fig. 29.

Principal groups of figures on the Hunter's Palette. After Smith 1949.

The doomed bowman is depicted as completely detached from the two regular files of his companion hunters. It is implied in the orientation of his baseline in relation to the other figures that he lies spread-eagled beneath the lion, whose decisive blow has just taken place. Like the dying lion at the bottom of the palette (for the viewer initially holding the palette upright, with long axis vertical), the doomed hunter's grounding is utterly torn from him: neither on his companions' ground nor in the lions', he is inserted "upside down" in the right angle formed by the intersection of the two groups.

The fallen bowman managed to shoot the arrow from his bow at the lion as it approached and pounced. One of his companions, the third hunter back in the right-hand file, apparently did the same; although his figure is now partly missing, he appears to run forward—toward the scene of confrontation—holding up his bow. At any rate the lion is depicted as having been hit by two arrows before mauling the surprised hunter.

At the top left curve of the palette, another hunter attempts to rescue or avenge his fallen companion. Leaning forward to fit an arrow to his bow, the approaching hunter reveals his right shoulder in profile and the quiver on his back, details not rendered for any other hunters in this image. Consistent with his status as the hunter who successfully kills the lion, he exposes more of the real site and force of his blow than the others—a force precisely to be found behind his back, on the other side of the usual side of representation. Furthermore, in confronting the lion the approaching hunter must strike out on his own ground, "twisting away" from his companions: on first glance he appears to turn sharply right out of the left-hand file of hunters. In fact he is now on the lions' ground; his baseline runs parallel with lion and cub. Evidently, then, the temporal and spatial unity formed by the four figures at the top of the palette—cub, lion, surprised hunter, and approaching hunter—is expressed in their disposition along the same baseline.

Supplanting the lion's natural victims presented in the carnivores-and-prey formula of other images (such as gazelles and lions on the Oxford Palette [Fig. 26]), the approaching hunter is the lion's antagonist in a confrontation (in time) following upon and (in space) replacing the first antagonists confronting each other—namely, the lion cub and the surprised hunter. This narrative sequence

breaks apart and interleaves the separate, symmetrical pairs of carnivores and prey of earlier images (like the two pairs of lions and gazelles on the Oxford Palette; Zone 1, Fig. 27). Viewing from right to left, the earlier and later confrontations appear as a continuity from before to after—namely (1), the lion cub (2) is defended by the lion (3), who attacks a hunter (4) rescued by the approaching bowman. But viewing from left to right, the story is not so much reviewed as understood to move on to the next stage of the action: after entering the lions' ground from his erstwhile place among the hunters (4), the rescuer shoots his arrow (3) over the body of the fallen hunter (2) into the head of the lion (1) attempting to defend its cub. Placed immediately above the four figures, the shrine with closed door, "to be opened and entered," and the joined foreparts of two wild bull oxen or buffalo "looking both ways" (Fig. 30) seem to indicate how this two-paired group is to be viewed—namely, from right to left (one "door") and from left to right (the other "door"), back and forth, producing the characteristic "mobility of internal elements" that establishes a pictorial narrative's "summation in time" (Lotman 1975; for discussion of this understanding of pictorial narrative, see the Appendix).[2]

Although stooping visibly, the hunter approaching to rescue his fallen companion is the tallest figure in the composition, like the ruler in the Decorated Tomb painting (Fig. 5) or like Narmer on the Narmer Palette (Fig. 38). He is also the topmost and the only "upright" human figure. It is he who is depicted about to shoot his arrow at the lion, to strike the decisive blow. Not counting the fallen hunter, the two huntsmen closest to him carry Falcon and Feather standards (royal standards of the West, if interpreted anachronistically, but otherwise simply emblems of the group's social affiliation).[3] On all these grounds, the topmost hunter is almost certainly the leader, the "ruler" of the group. "The rather clumsy way in which the bowman has been represented has often been pointed out" (Baumgartel 1960: 97); like the bobbing, masked hunters on the Ostrich and Oxford Palettes (Figs. 25, 26), he ducks, twists, and insinuates himself into the proper position rather than marching straight into things. His stooping profile aspect, ignored in all existing commentaries, seems a literal depiction of his sideways entry into the lions' ground.

By contrast, with two exceptions all the hunters unengaged with the lion march fully upright on a more or less straight baseline along the side edges of

Fig. 30

The "shrine" and "double bull" on the Hunter's Palette. After Smith 1949.

the palette. They fail to see the lion cub and the danger posed by the lion, for they are oriented at right angles to the scene of confrontation. They are also at right angles to the viewer's initial view of the image (holding the palette vertical). To bring them upright the viewer does not just look right or left but must literally turn the palette downward to the right or the left; in doing so the viewer will, like the hunters, fail to see the decisive blows of the principal antagonists, the lion (who has already struck) and the ruler (who is about to strike). Turned to the right or to the left with its long axis horizontal, the image depicts what is before, what is after, or what is simultaneous with the scene of confrontation—and moving it to the upright will be to see what the hunters on the edges, moving into the scene of nature, could not themselves see awaiting them there. The viewer's position, then, shifts depending on how the palette is held and the image spread across it is viewed: the viewer oscillates from being like the ruler to being like the other hunters and vice versa.

Behind the Back

So far we have dealt only with the first group in the image (Fig. 29, Group 1) and its relation to the two files of hunters along the edges. At first glance the ruler appears to turn sharply "right" out of the left-hand file of hunters to confront the lion directly, face-to-face. The apparently straight lines of his straight arrows do not fly straight ahead, however, as they would if hunter stood directly before lion. Rather, they twist or angle in a visibly downward, rightward direction into the lion's ground. Their trajectory figures, or prefigures, the viewer's own next move—namely, to turn the palette down from the upright (long axis vertical) to the right (bringing the long axis to the horizontal). Despite appearances, then, the ruler—perhaps because he is not masked by the features of an animal—is on the lion's ground only in an oblique position. In fact, although the ruler appears to confront the lion face-to-face, the fallen hunter masks him from the lion, who is actually killed from behind. Facing to the "right" at the topmost position in the composition, the ruler is not the eleventh person in the left-hand row of hunters but rather the eighth and foremost in the right-hand row, almost matching the full complement of ten in the other file.[4]

The scene of representation on the Hunter's Palette incorporates on its one and only side the twisting flip required to interpret the two-sided image on the Oxford Palette (Fig. 27). The lion breaks into the right-hand file of hunters from its "right"—that is, from outside the scene altogether—and the ruler, in turn, backs out of the right-hand file so as not to turn and face the lion but to go around behind it. The ruler's arrow flies, as it were, around the palette, taking an elliptical path through a "wild" space unrepresented in the image before hitting the target decisively; in passing out of and back into representation, the arrow masks the depiction of the blow literally falling (see Fig. 32). The ruler's motion and the act of killing the lion are unfolded by moving the palette: when the viewer twists the upright palette (long axis vertical) down to the right, tracking the downward trajectory of the ruler's arrow and moving into the "next" unit of the narrative, the ruler appears to move downward to be brought up, as it were, behind the lion at the "bottom" (now left) of the palette. Here the beast is shown "upside down," placed on the same long horizontal axis as the files of hunters but facing away from them—that is, not seeing

the ruler "behind" him (see Fig. 29, Group 2). The two arrows fired earlier at the lion's head, presumably one by the fallen hunter and one by his running companion in the right-hand file (third hunter back), are now reinforced by three more arrows shot at and into the back of the lion's head. It is probably not the ruler who fires these three arrows; the sixth hunter back in the left-hand file—who could also be "behind" the lion—is depicted as entering the scene carrying precisely three arrows. But making six shots in all, a fourth and final arrow fired during the "rescue," the only fully straight shot along the line of the ground and evidently the ruler's decisive shot, plunges into the lion's anal-genital region.[5]

There could hardly be a more explicit depiction of the lion's unfortunate fate. His natural ability to strike his own blow—in the top scene (Fig. 29, Group 1) his powerful legs and claws and open jaws appear to be a match for the hunters' weapons—was, it turns out as the viewer unfolds the narrative, pointed in utterly the wrong direction. As on the Ostrich and Oxford Palettes (Figs. 25, 26), the hunter's mastery of nature takes place where nature cannot see it, moving up from the sidelines, "behind its back," to close a deadly circle. When the hunter enters the scene, even the clearest sightlines and straightest shots take a deadly turn.

A Natural Interlude

So far we have seen the story of the lion's death in two episodes—first, the lion's attack on the surprised hunter to defend its cub and, second, the ruler's corresponding attack on the lion to rescue or avenge his companion. Although the story follows the "natural" chronological order of events, the pictorial text presents them elliptically. The ruler's blow is not directly depicted; instead, in the first unit of story-text (Fig. 29, Group 1), the ruler prepares to strike his blow (fits an arrow to his bow) and in the second unit of story-text (at the bottom of the palette), the blow has fallen (the lion has been killed). As in other images in the chain of' replications, the spatiotemporal and causal relations of the narrative, its logic of before and after, can be rearranged in the sequence of presentation into alternative, complex combinations at the very same time as the pictorial text offers its oblique representation of the episodes in the sequence.

On the Hunter's Palette the relation between the actual chronological and causal logic of events and their presentation in the composition of the image is not entirely clear. The other zones of the image (Groups 2, 3, and 4) do not seem to depict additional episodes in the death of the lion (Groups 1 and 2), although they might be regarded as variously before or after that main event. Rather, they repeat or rehearse its general theme in a context that depicts different actors and events, like a second narrative running alongside the main story. Whether or not they are events literally continuous with or before or after the lion's death, they have been folded into the pictorial text of the story of the lion's death and must be viewed along with it as a kind of metaphorical shadow.

It is likely that the Hunter's Palette relates a single large-scale narrative of various events of the hunting expedition as a whole, broken into two "chapters" in the presentation. These chapters relate either sequential or simultaneous and—a more interesting point—metaphorically associated episodes (the lion's death in Groups 1 and 2, and the wild animals' hunt in Groups 2, 3, and 4), each chapter containing two scenes (therefore four scenes in all) related to the story in such a way that one of the most crucial events in the full narrative, although presented in its preconditions and results, drops into ellipsis. This structure seems to be a revising replication of the structure to be observed on the Oxford Palette (Fig. 27), where each of the two sides includes two zones (top and bottom), or four textual zones in all. Turning now to the other zones of the image on the Hunter's Palette, we find (in Group 2) an antelope in the row of animals on the same baseline as the defeated lion turning its head to see a confrontation—a jackal pouncing on its prey—it successfully manages to evade. The jackal and the fleeing deer or stag (which does not see its enemy) form a typical carnivore-and-prey pair, framed on the "left" by the doomed lion, defeated by his own flawed sight, and on the right by the escaping antelope, saved by proper sight.

For an image maker or viewer who had seen the Oxford Palette (Fig. 26) or similar images, the jackal could presumably be a deliberate metaphor for the human hunter who wore its mask in the earlier replication. But even if this equivalence was not intended, a direct association between the story of the lion's death (Groups 1 and 2) and the wild animals' hunt (Groups 2, 3, and 4) is

clearly made, for Group 2 also presents the jackal's attack, repeated, in turn, in other ways in Groups 3 and 4. Thus the viewer can unfold the entire image as a set of possible metaphorical relations that function independently as a continuous narrative.

The center of the image, around the cosmetic saucer, includes two extraordinary groups (Groups 3 and 4) tying together the principal top/bottom and left/right axes of the composition. In the pictorial metaphorics they juxtapose the hunters' mastered ground and the ground of nature, containing its own contests but contested by the hunters.

Immediately below the cosmetic saucer (Group 3), a gazelle—on the Oxford Palette the prey of the lions—runs in the same direction as or even "toward" the left-hand file of hunters; the gazelle looks back over its shoulder at a hunter there about to throw a lasso at the melee of animals. Running past the gazelle in the other direction, a jackal directs a backward glance at it. Like the bowmen and lions at the top of the palette (Group 1), this group (Group 3) depicts the moment just before the blow.

Immediately above the saucer and below the bowmen and lions (Group 4) is the moment just after the blow: the scene below the saucer (Group 3) is literally flipped over from bottom to top and left to right and advanced a moment in time beyond the decisive strike, like the depiction of the defeated lion at the bottom of the palette (Group 2) in relation to the figure of the ruler at the top (Group 1). The antelope is caught by the horns with a lasso thrown by a hunter in the right-hand file who now leans forward to pull in his victim. Unlike the fleeing gazelle, the antelope above the saucer turns its head around to look back only to mistake its real pursuer, for it is depicted as turning back to see the jackal instead; the jackal is now flipped over and reversed in direction running toward and along the "right" side of the antelope about to pounce on it. Precisely as it did on the Oxford Palette, the jackal running along the ground line of the lasso masks the deadly power of the antelope's real enemy—the hunter—who, wearing the tail of the carnivore, comes up behind the antelope as it looks at the jackal.

Groups 2, 3, and 4, then, present a continuous story ranged along the baseline established by turning the palette down to the right and bringing its

long axis to the horizontal. First (Group 2) the jackal chases the stag while the antelope, turning its head, flees ahead of it. Next (Group 3) a gazelle in the melee of beasts—fleeing their pursuers but at the same time encountering the files of human hunters moving through the brush—sees the hunter in the left file preparing to throw his lasso at the animals. Running past the gazelle in the other direction, "toward" the antelope in Group 2, a "twin" of the jackal—that is, the "same" jackal—from Group 1 in turn sights the gazelle. Finally (Group 4) a "twin" of the antelope—that is, the "same" antelope—from Group 2 turns its head around to the other side to see the jackal coming toward it, as depicted in Group 3, but in so doing fails to see the hunter, in the right file, throwing the lasso that catches it (Group 4). The gazelle presumably escapes—after all, the gazelle's antagonist in the earlier replication, the lion of the Oxford Palette, is otherwise occupied—for in the terms of the narrative image, the action from Groups 2 through 3 and 4 passes it by.

Group 3 is separated from Group 2 by the figure of an ostrich running along the ground and flapping its wings; Group 4 is separated from Group 3 by the figure of a bounding hare. In the literal depiction these creatures are presumably part of the melee of wild animals being pursued by the jackal(s) and human hunters. But like the shrine and double bull at the top of the image, they also indicate, for these portions of the image, how the narrative image should be read—that is, at least for this central passage (as it is brought into view by having turned the palette down to the right), not by going back and forth or right and left but instead by "flying" or "hopping" to the next, "later" piece of ground, from Group 2 to Group 3 to Group 4 as the stages of a continuous action. Certainly the ostrich in Group 3, if the image maker or viewer had seen the Oxford Palette (Fig. 26), would have had an established textual function of this kind, and the hare, placed in the same position in the next group (Group 4), could be construed likewise. Once the viewer comes to the end of the central passage of depiction along the long horizontal axis, the top scene (Group 1) is reencountered; the first instructions of the "double door" and bull—go back and forth, right and now, presumably, left—apply again.

In the entire central passage of the image (Groups 2, 3, and 4), the hunter's blow is not depicted. It falls between Groups 3 and 4, just as occurs between

Groups 1 and 2, where the cosmetic saucer intervenes in the composition of the image as a whole—that is, in a wild, unrepresented place where the human owner of the palette reaches down to mix eye paint and mask his or her own face before entering the scene. It does not matter here whether the palette was used to prepare for an actual or a ritual, ceremonial hunt, to recall or commemorate one, or to depict something else altogether for which "hunting" and "masking" are the appropriate metaphors. Its pictorial mechanics and internal metaphorics dictate in the central passage of depiction the metaphor of masking the blow: the huntsman's lasso takes the same angling turn, coming around and out from behind what masks it, as the ruler's deadly arrow fired at the lion.

Two Turns, Looking One Way and the Other

The figures of the hunter lassoing the antelope and the figures of the lion mauling the fallen hunter are clearly meant to be viewed in relation to each other. They may be either successive or simultaneous episodes in the narrative chronology, perhaps arranged as above and below although the pictorial text—the site of metaphorical linkages—requires that they be viewed together. Both groups appear in the portion of the image above the cosmetic saucer, the zone the viewer is first likely to inspect and ordinarily where late prehistoric images of this sort begin to unfold. Moreover, it seems to be no accident that the viewer cannot quite distinguish the fallen hunter from the doomed antelope, their arms and legs tangled together and both oriented "upside down" in the scene to which they belong: both have been destroyed by what they did not see. In fact the fallen hunter in Group 1, the viewer might now conclude after having surveyed the central passage of depiction (Groups 2, 3, and 4), stumbled across the lion cub and provoked its sire precisely because he was watching or helping his companion lasso the antelope that failed to see its danger; there is, certainly, a narrative (re-)connection between Group 4 and Group 1, completing the movement or circle of the entire viewing. We can also see now that the viewer is constituted as akin to fallen hunter and doomed antelope. Lured by the apparent order of the image, the viewer falls to see the decisive blows occurring

outside, around, or deep within it—placed, in the image, where the depiction goes blank at the point of its interruption by the cosmetic saucer.

The top area of the palette above the cosmetic saucer is both the "beginning" of the image and a passage of depiction (re-)encountered after working through all four groups—for example, when the palette is brought upright again after the central passage, with long axis horizontal, has been surveyed. Thus, as a passage of metaphorical and narrative relations between what the viewer unfolds as Groups 1–2 and Groups 2–4, the top area of the palette measures human success, the hunter's victory over the antelope, against human defeat, his companion's destruction by the lion. But the forces of man and nature are not equally matched; there is much more to the story. Whereas man can imitate nature, nature cannot imitate man. Whereas nature, in the pair of a carnivore and its prey, must literally confront itself in its contests, therefore always having opportunity to see its danger (the narrative message of the Oxford Palette), man stands back and strikes from the sidelines. He fills the gap between the unseeing target at a distance from him and the real ground of his deadly force, an advancing edge coming into the scene, with all manner of costumes, lures, traps, projectiles, and masks—in general, with representations.

Like the decorated knife handles (Figs. 8, 9, 11, 20–23) and the Oxford Palette (Figs. 26, 27), the image on the Hunter's Palette has a tight structure (Fig. 31). "We are in the time and space of the sign, a sign that brings into play a representation of each of the orders of life—carnivore, herbivore, and human—and establishes among them a relation of combat" (Tefnin 1979: 225). Although our interpretation cannot be confirmed by independent external evidence, it seems that no figure is left out of the representational mechanism pivoting around the wild space of the cosmetic saucer—its central node—upright, down to the right, back upright, down to the left, and repeated, just as many individual figures throughout the image pivot on their own axes.

As with the ostrich launching its flight and the gazelle with twisted horns on the Oxford Palette (Fig. 27), a series of cipher keys, four in all and corresponding to the four groups of the image, guide—by representing—the motions of and for the viewing of the Hunter's Palette. We can choose to understand them as symbols activating or "narrativizing" the otherwise static image

(for this quality of pictorial narratives, see the Appendix). The "shrine" and the joined foreparts of two wild bull oxen or buffalo at the top right curve of the palette (Fig. 30) should probably be read to say "go through the door on the left and look back and forth, left and right, up and down," while the flying ostrich and leaping hare should be read to say "jump to the next stage." In their preliminary position within the pictorial text, like the wild dogs on the Oxford Palette, the topmost signs probably also announce the theme of the image—to be provided with metaphorical and narrative substance in the very viewing they prescribe for the viewer. The open door of the "shrine" is on the left, while its right side is a closed, blank facade, corresponding to the positions, the actions, and the fortunes of the two chief actors in the tale, ruler on the left and lion on the right. The bulls look in both directions at once, but as individuals the bull on the left cannot see what is to the right and the bull on the right cannot see what is to the left—a condition corresponding generally to all the identities in the image, except for that of the ruler, who is precisely in the place of or able to go through the door and become the "double bull," that is, able to see in both directions at once.[6]

Having surveyed the various elements of the image, we can now review the "looking one way and the other" constructed by the pictorial mechanism (Fig. 31) by going through the ordered temporal activity of viewing.[7] Initially holding the palette upright (long axis vertical), the viewer sees, on the short horizontal baseline at the top of the image, the lion just after striking down the doomed hunter but also just before the ruler strikes his decisive blow against the lion. That blow is not literally depicted in the scene; at the bottom of the palette the lion is shown as defeated, the decisive blow having fallen. Here, like the hunter he had destroyed, the lion has been pivoted from his earlier horizontal axis and turned "upside down" to represent his own death.

In examining this scene of confrontation and following the instructions of the "double bull," the viewer traces the implied trajectory of the ruler's arrow and turns the palette down to the right, moving the ruler "down," "around," and "behind" the lion. The palette is now reoriented in the viewer's hands with its long axis horizontal to the viewer's line of sight. With the bottom lion now appearing on the left side of but facing away from the files of hunters, the viewer

Fig. 31.

Viewing the Hunter's Palette. After Smith 1949.

begins to see properly how the beast was slain. (In other words, from Group 1 to Group 2 the pictorial text shows the viewer how the lion was killed after showing it about to be killed; it moves from a "present" to a "past" tense.) In particular, the viewer notices the arrows penetrating the lion from behind, three arrows in the back of its head and one arrow in its anal-genital region.

Scanning from the doomed lion on the left, from left to right along the long horizontal back into the scene, the figures turning up next in the time of the viewing—the jackal, the unseeing stag, and the escaping antelope (Group 2)—represent the victim's alternatives: namely, seeing the force coming up behind (and escaping) or failing to see (and being destroyed). Next on the horizontal as viewed from left to right, the following figures (Group 3) depict the moment just before the lassoing, while the final figures (Group 4), on the other, right side of the saucer, depict the moment just after the lasso has coiled over the antelope's horns. Both groups around the saucer represent the attack from behind and mistaking the mask for the blow—that is, they metaphorically, re-present the death of the lion.

For the viewer holding the palette with right side down, the last figure on the long horizontal, the doomed antelope, is now "upside down." That is, the antelope is in the same position of "death" as was the doomed lion when the palette was upright. Once the viewer brings the palette back upright to its original position, with its long axis in vertical and its short axis in horizontal orientation, Group 1—ruler, fallen hunter, lion, and cub—comes into view again so that it can be more fully understood. The text returns—now in a "past" tense—to the episode it had already partially related; the viewer now sees the lion's danger clearly and knows in advance what its consequences will be, because the text has enabled (in Group 2) a "look ahead" at the lion killed from behind.

But the action of viewing does not end here. To bring the fallen antelope upright, the viewer must continue to turn the palette on its pivot downward to the left. Holding the palette in this orientation, with the left side down and the top of the palette to the viewer's left, the real truths of the scene are made fully visible. The text goes through the narrative chronology of events one more time with complete retrospective clarity. The doomed antelope and lassoing

hunter now become upright for the viewer. At the same time the jackal running "upside down" beside the antelope reveals itself to be intervening between antelope and hunter; it becomes a forward mask for the antelope's true danger, what the antelope manages to see when to save itself it should see its human enemy. In parallel the doomed hunter mauled by the lion is equally revealed as what masks the ruler, coming up behind the lion, from the lion's sight; while the lion faces the fallen hunter, the ruler edges into position behind the beast to shoot the fatal arrow. The remainder of nature, for the viewer now on the right side of the saucer along the long horizontal axis, is entirely "upside down"; that is to say, it is revealed as target and victim of the hunters' blows—as what has died or will do so—like the antelope and the lion itself. At the beginning of the story the hunters march into a nature that does not observe them. In the viewer's first viewing orientation the animals engage only themselves, upright and at right angles to the hunters. But now, at the end of the story in the viewer's final viewing orientation, the hunters march out of nature, having mastered it. The "upside-down" lion at the far right end of the image, facing out of the scene altogether, is returned, destroyed, to the place outside the files of hunters whence it first advanced.

Finally the true directions and targets of the hunter's lasso and the ruler's arrows become visible. The lasso, snaking out from the file of hunters with the jackal running along it (a visual conceit employed on the Oxford Palette, Fig. 26), figures the double twist required to interpret the image (Fig. 32); holding and moving the palette upright, down to the right, upright, and down to the left unfolds the narrative. The hunter employs the lasso to wrest the antelope onto his own ground; the throwing of the lasso is one of the main events of the narrative. In the pictorial text—in the formal functioning of the image itself—it is a literal ground line along which the human hunters' forward masks are advanced; it takes possession of the represented world, contested unsuccessfully by the lion. Natural master in nature, and even threatening the regularity of human order as he tears the doomed hunter from his baseline, the lion still lacks the force of representation. Unlike the human ruler, the lion cannot assume a distance from his target and advance a representation against it, and consequently he is mastered by the ruler's arrow fired from behind.

Fig. 32.

The ruler's arrow and the hunter's lasso on the Hunter's Palette. After Smith 1949.

The spatiotemporal logic of the events related in the image requires that the ruler's arrow fly straight from his bow to strike its target; but in the story as it is depicted, we are given only the preconditions (Group 1) and the consequences (Group 2) of this action. In the pictorial text, the literal depiction within the image, the arrow must in fact fly "outside," "over," and "around" the scene to get from its initial to its target position. In the first viewing orientation (long axis vertical), the arrow launched by the ruler (Group 1) must fly "around and behind" the lion and "down" the palette itself (to Group 2); and in the final viewing orientation (long axis horizontal, left side down), the arrow must fly "over" the scene of the hunters' mastery of nature (reading from left to right, "over" Groups 1, 4, 3, 2) to hit the lion. The lasso, by contrast, is thrown in the other direction; it moves up from below (in the first viewing orientation), from left to right (in the next orientation, with long axis vertical and right side down, it is thrown by the hunter in the left-hand file), and from right to left (in the final orientation, with long axis vertical and left side down, it is thrown by the hunter in the right-hand file). Since the flight of the lasso is directly depicted while the flight of the ruler's arrow is not—in the final viewing orientation the arrow crosses "over" the lasso going in the other direction—the lasso, like the jackal running along it, is in itself a metaphor for the ruler's blow.

The flight of the ruler's arrow links the top and bottom of the image just as the lasso ties together the left and right. Indeed, to link the first (top) and second (bottom) stages of the scene of the lion's destruction—to connect before and after—the path of the arrow about to come around behind the lion, at the top, and then plunged into him, at the bottom, is to take the very twist the image literally provides for the end of the lasso representing the ruler's decisive force within the depicted scene. In fact, like the end of the lasso, the arrow must make a complete circle, equivalent to turning the palette all the way around its pivot. But this circle, the flight path of the ruler's arrow, could never be literally depicted. In the first viewing orientation (long axis vertical), the arrow can fly "down" the right side, but cannot hit the lion at the bottom, who is "upside down" in relation to the orientation of the ruler at the top; and in later viewing orientations (short axis vertical), the arrow can plunge into the

lion at the bottom, who is hit from behind, but cannot at the same time be seen as coming from the ruler, never depicted as standing "behind" the lion on the long horizontal axis but always necessarily at right angles to it, "upside down," from the vantage point of a lion who is not able to see him. Thus the arrow's flight, the deadly circle enclosing and destroying the lion, hovers somewhere above and outside the depiction. In this wild space the oblique force of the ruler's blow, advancing behind representations, escapes representation. It is here too that the viewer twists the palette back and forth, pivoting it around itself, in mastering the depicted scene of mastery.