| • | • | • |

During the publicization process, in a wide variety of human activities, groups of spectators formed and swelled and separated from actors, while, reciprocally, the latter made their activities more distinctive in order to try to attract and appeal to the new, larger, and more distant audiences. Actors in the nontheatrical sense became actors in the theatrical sense, indeed actors of a particular kind of theatricality. They gave their activities éclat—brilliance, flash, fanfare, zip, flamboyance—that is, they turned their activities into spectacles.

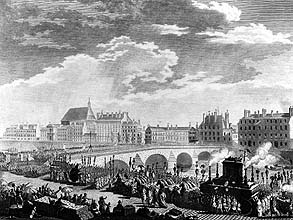

The Revolution was a gigantic spectacle. Its principal events consisted in large part of crowds of people coming together in public, whether to demonstrate for political and economic goals in the streets, to debate and enact legislation in the new representative assemblies, to celebrate and forge national unity in parks and gardens, to drill and fight as soldiers and national guardsmen in fields, or to witness executions in town squares.

Particularly characteristic of the Revolution were its fêtes, celebratory gatherings organized by the government with programs of parades, music, speeches, banquets, dedications of monuments, and other ceremonies that took place in the Grands Boulevards, the Jardin des Tuileries, the Champ de Mars, and other large public spaces of Paris, as well as in provincial cities and towns. Assemblies of one hundred thousand or more people were not uncommon at the Paris fêtes. In La Fête révolutionnaire, 1789–1799, Mona Ozouf argues that, in spite of the variety of their occasions, a funeral, an anniversary, a military victory, or religious worship, these fêtes had a certain unity of design—the enactment of a vision of utopia—and that this design was also that of the Revolution itself.

Ozouf acknowledges her indebtedness to Jules Michelet, the great nineteenth-century nationalist historian of the Revolution, who believed, as she puts it, in the “consubstantiality of the fête with the Revolution.” But Michelet, she observes, rather than focusing on the official government celebrations, assimilated a variety of different kinds of public gatherings, especially spontaneous formations of activist crowds, into the meaning of the word “fête.” In Michelet’s view, as the Revolution unraveled, veritable fêtes devolved into contrived fêtes, fêtes staged by the government that did not reflect popular feeling, however well attended they might have been.[18]

Michelet’s view of fêtes, in turn, was influenced by Rousseau, drum major of the Revolution, who wrote in his “Lettre à d’Alembert sur les spectacles” that “the only pure joy is public joy.” In the same work Rousseau expressed his disapproval of theater and his approval of programless outdoor fêtes in which large numbers of people participate: “Put the spectators into the spectacle; make them actors themselves; allow everyone to see oneself and love oneself in others, that all may be more closely united.” [19]

But as the Revolution proceeded, fewer and fewer public assemblies were spontaneous, and in fewer and fewer of them were the crowds real participants. Public activities were superseded by public spectacles.

Jacques-Louis David is best known today as the foremost French neoclassical painter, somewhat less well known as a leading revolutionary, and hardly known at all as a designer of fêtes. Although under the Old Regime he had been accepted into the exclusive Académie Royale de Peinture et Sculpture and been given a studio in the Louvre, he still felt stifled by the patronage system of the art establishment. He turned into an outspoken advocate of the publicization of art, arguing for open exhibitions of new works and open competitions for government commissions. With the advent of the Revolution he became not only the official image maker of such important events as “Le Serment du Jeu de paume” (The Oath of the Tennis-Court) and “Marat assassiné,” but also, as one historian has called him, the pageant-master of the republic. David designed the costumes, the plaster monuments, the stage sets, the parade vehicles, and other props for several of the most important government-sponsored fêtes of the early years of the Revolution. For example, when the revolutionaries decided to transfer Voltaire’s remains to a recently completed neoclassical church that they had rechristened the Panthéon, David conceived a Roman procession for the occasion, designing with motifs from antiquity a huge horse-drawn hearse, and outfitting its attendants with togas, lyres, spears, helmets, poles topped with eagles, even a few sedan chairs. As many as one hundred thousand people, not all of them in Roman attire, marched in the procession, and perhaps another one hundred thousand watched.[20] The route was clear: neoclassicism first as art of the privileged, then as public art, and finally as public spectacle.

The revolutionary spectacle par excellence was oratory. The representatives to the new assemblies ruling France had no experience or connections in government, were unknown to the public, and did not know each other. Those who acquired fame and power did it through successful public speaking, whether in the assemblies, in the streets, or in the political clubs. The speeches judged to have made the biggest impact were reproduced in summary or at length in the many newspapers that suddenly sprang up after the abolition of privilèges. These newspapers were expedited from Paris to all corners of France, and of Europe, where they were eagerly read. Oratory, like theater, became a mania. “Who isn’t an orator?” asked Sébastien Mercier. “Who doesn’t dream of being an orator, with this great and pleasant prospect?” [21] The quality of the oratory increased with practice and with increasing danger. Immediately before and during the Reign of Terror, what one said in public determined whether or not one stayed alive, encouraging prudence in choice of words. If one kept one’s head, one kept one’s head. Nevertheless, from the obscene, wildly gesticulating, unkempt and uncouth Hébert to the erect, wigged and powdered, self-controlled in manner if not in matter Robespierre, both of whom lost theirs, the Terror was one continuous fountain of crimson prose—and, of course, blood.

The guillotine repeated the same scene again and again, but never bored the audience. On a succession of increasingly spacious public squares in Paris, the Place de Grève, the Place du Carrousel, the Place de la Concorde, the Place du Trône, and in analogous locations around France, the whoosh, thwack, thud of the blade and head remained constant while the subsequent cheers of the increasingly large and more frequently assembled multitude grew wilder. Eighty thousand armed men lined the route between his prison and the Place de la Concorde when the deposed King Louis XVI made the short trip to his “shortening” in January 1793. After he was executed and the twenty thousand attending troops dispersed, there was jubilation and dancing around the scaffold.[22] Those who wanted to watch the enemies of the Revolution perish in greater numbers could travel to the borders of France, where a protracted series of wars against the monarchies of Europe began in 1792.

Figure 11. Two revolutionary spectacles. Spontaneous: Burning of the Pope in effigy at the Palais-Royal (top). Planned: Triumphal procession designed by Jacques-Louis David for the transfer of Voltaire’s remains (bottom). Author's collection. Photographs by J. Craig Sweat/Photographer.

Napoleon’s proclamation of the Empire in 1804 suspended public government, but not government-sponsored public spectacles. In fact, the Em-pire began with a grandiose neo-medieval ceremony in which Napoleon crowned himself emperor in the presence of the pope, a ceremony whose official representation was painted by Jacques-Louis David on a canvas thirty feet long and twenty feet high.[23] The fêtes of the Empire were predominantly military: reviews and parades featuring artillery, cavalry, and infantry in showy dress uniforms abundantly decorated with gold braid and embroidery and topped with bicorn hats, fur bonnets, Roman helmets, and shakos with tall plumes; presentations of crosses of the Légion d’Honneur and other medals; and distributions of neo-Roman regimental eagles, also the subject of an enormous painting by David, who had already used such eagles himself in Voltaire’s funeral procession.

The greatest spectacles of the Empire were not the fêtes of Paris and other French cities, however. They were instead Napoleon’s monumental battles, which had exotic locales for their theaters, which were the subject in France of exalted journalistic accounts and exalted pictorial representations, and which exhausted the Revolution’s spectacle of blood. As Napoleon himself said: “My power depends on my glory, and my glory on my victories. My power would fall if I did not sustain it with more glory and more victories.…A newly established government must dazzle and astonish. As soon as it stops throwing sparks, it falls.” [24] Thus, government became spectacular.

So did theater. Napoleon and his contemporaries loved theater but they adored spectacle. The emperor often attended performances of François-Joseph Talma, the foremost French tragedian of his day, engaged him in conversations about acting, and considered awarding him the cross of the Légion d’Honneur.[25] But it was Madame Saqui, the tightrope walker, whom he invited to participate in the celebrations of his name day, to entertain his soldiers in their camps, and to add variety to his military fêtes. He even summoned her to Vienna when he captured that capital. Her biographer writes:

After the collapse of the Empire, she bought a theater on the Boulevard du Temple, where her performances maintained their popularity for many years.[26]During that epoch of military glory, her great popularity increased even more when she thought of miming, on the tightrope, by herself, the battles and victories of the Empire.…Armed with a saber, she pretended to lead a furious charge whose momentum forced the imaginary enemy to retreat, or…stopping to shoot, she kneeled to fire, then fixed a bayonette on her rifle, and advanced irresistibly, or suddenly fell, as if she were wounded, flinging herself up again to plant on the pole a flag she carried wrapped around her waist.

Theater historian Marie-Antoinette Allevy summarizes the first half of the nineteenth century as “that era of French theater during which an extreme consideration was accorded, in every genre of drama, to the ‘spectacle.’” In that era, she argues, the mise-en-scène—the sets, props, costumes, lighting, and sound effects—gradually overwhelmed the literary aspects of drama—the dialogue, characters, and plot. “In the boulevard theaters, the division into acts disappeared in favor of the division into pictures [tableaux]. Ten, fifteen, twenty pictures succeeded one another in a single piece, each necessitating an appropriate decor.” It was the era of melodrama, of fantastic ruins, gothic palaces, pirate ships, nature at its wildest, the city at its rawest, of violence everywhere. “The technicians, the machinists, the decorators, the builders of props and sets exercised their imaginations to create new and original contrivances and devices: representations of the sea, of shipwrecks, drownings, fires, floods.” Like the actors, the technicians came out on stage at the end of the play to receive their applause, sometimes the loudest and longest ovations. The contemporary critic Théophile Gautier announced, “The era of purely ocular theater has arrived.” [27]

The fêtes of the Revolution contributed to this development. “We owe to Jacques-Louis David,” acknowledges Marian Hannah Winter, another theater historian, “usable scenery made to be climbed up, into and over to a degree not previously imagined. We also owe to him the marshaling and management of those hordes of extras who appeared in battle, ballroom, parade and harvest scenes, filing through the streets, squares and public gardens, and finally onto the stage itself.” Other spectacles also invaded the theater. In 1768 the Englishman Philip Astley “was the first to introduce acrobats, rope-dancers, and short mimed or dialogued scenes into what had been purely equestrian spectacles.” In 1782 he built on the Boulevard du Temple Paris’s first permanent circus—literally, “circle”; commonly, a mixed equestrian spectacle in a circular space. The Amphithéâtre Astley evolved into the Cirque Olympique in 1810 and began incorporating its feats of horsemanship and acrobatics into whole, connected stories, for example Murat, a dramatization of the life of Marshal Murat, the head of Napoleon’s cavalry. This subject allowed for the re-presentation in the heart of Paris of some of Napoleon’s most spectacular battles, the occasion of Gautier’s remark quoted above. Other boulevard theaters featured trained dogs, monkeys, lions, and tigers in their plays. Rope-dancers and mimes, led by Jean-Baptiste Deburau of the Théâtre des Funambules, expanded their vignettes into full-length dramas.[28] All this represented the French Revolution of the stage. Before the Revolution, in order to evade the restrictions imposed on them by the privileged theaters, the theaters of the fairs and the boulevards had cultivated these “lesser” theatrical arts, the arts du spectacle, as the French call them; after the Revolution abolished the system of privileges, the arts du spectacle began to take over theater proper.

Theater evolved into spectacle and/or spectacle invaded theater. Any way one looks at it, theater became spectacular. The same thing happened to painting, to science, to technology.

The incidents in the career of Jacques-Louis David that have already been mentioned indicate one way painting became spectacular. Another was through experimental kinetic picture shows, several with names ending in “-orama” (Greek for “sight”), which became extremely popular in the first half of the nineteenth century. A panorama had an outdoor scene painted on the wall of a rotunda, so that it encircled the spectators. Sometimes the spectators stood or sat in darkness and watched while lights played on the painting, animating a sunrise or a thunderstorm, or while actors used the painting as a three-dimensional backdrop. Sometimes the spectators walked around the rotunda, enhancing the three-dimensional appearance of a painting done in relief or with sculptural forms included. Louis Daguerre, before he invented photography in the late 1830s, created the Diorama, a series of large paintings on transparencies lit from behind. The transparencies were set in frames so that they could be lowered to and raised from the stage in sequence. One popular sequence depicted the eruption of Vesuvius. E. G. Robertson produced a much imitated magic lantern show called the Fantasmagorie. He entombed his theater in a disused Paris monastery where the ancient stone walls, musty smells, flickering candlelight, and the eerie strains of a glass harmonica reinforced the effect created by his projection of indistinct images, which he convinced his spectators were ghosts of their deceased relatives or of martyred revolutionaries such as Jean-Paul Marat.[29] But the revolution in this kind of spectacle did not take place until the end of the century, when the Lumière brothers invented cinematography.

The popularity and convincingness of Robertson’s Fantasmagorie owed as much to his reputation as a scientist as to his brilliant staging. For in his shows he not only raised specters but also gave demonstrations illustrating recent discoveries in acoustics, mechanics, and electricity. When Alessandro Volta, the inventor of the battery, came to Paris, Robertson be-friended him and helped him win recognition for his research on the nature of electricity by giving public lectures and expériences and a joint presentation before the Académie des Sciences, which awarded Volta a silver medal. The word expérience was ambiguous, meaning either “experiment, test,” the basis of science, or “experience, apprehension by the senses,” the basis of spectacle. Which were the expériences of Comus, who discharged electricity into gemstones and lodestones, sensitive plants and neurasthenic people, curiosity seekers and cadavers, and who presented his findings both in reputable scientific journals and in his hall on the Boulevard du Temple? Which were Franz Anton Mesmer’s expériences of “animal magnetism” that found so receptive an audience in Paris after the Viennese medical establishment had censured the inventor/discoverer of what became known, first, as mesmerism and later as hypnotism? And which were Georges Cuvier’s reconstruction of mastodons, pterodactyls, and saber-toothed tigers for museum display at the Jardin des Plantes? The popularity and convincingness of Cuvier’s public lectures, in which he predicted that comparative anatomists would soon be able to deduce the complete appearance and lifestyle of extinct animals from the discovery of a single bone, owed as much to his brilliant staging as to his reputation as a scientist.[30]

E. G. Robertson was also an early aeronaut who flew in both balloons and parachutes,[31] two late-eighteenth-century French inventions the tests of which often took place above large audiences in such public places as the Jardin des Tuileries and the Champ de Mars. But the main stage for technology was the industrial exposition, the nineteenth-century forerunner of the twentieth-century world’s fair. In France, the first Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie took place in a temporary building erected in the Champ de Mars in 1798. Ever larger and more lavish expositions took place in 1801 and 1802 in temporary buildings in the courtyard of the Louvre, in 1806 on the esplanade of the Hôtel des Invalides, in 1819, 1823, and 1827 in the Louvre itself, and beginning in 1834 at regular five-year intervals in various public spaces.[32] Technology’s successful siege of the Louvre meant its conquest of a status equal to that of fine art as a public spectacle. Everything converged in spectacle.

Virtuosity converged in spectacle. Mechanicians had built automata for scientific purposes, for sale to the wealthy, for the amusement of princes. Mechanicians had also built automata for spectacles in Paris, showing them in rented rooms, at the annual fairs, and in permanent exhibition halls on the Boulevard du Temple and in the Palais-Royal. Robert-Houdin presented several inventions at the exposition of 1839 and then his automaton Writer-Sketcher at the exposition of 1844, gaining a silver medal from the judges of applied science, attention from King Louis-Philippe, admiration from the public, and a sale to P. T. Barnum.

Music and technology converged in spectacle. Adolphe Sax also won a silver medal at the exposition of 1844, for his saxhorns, instruments resembling flügelhorns. But musicians resisted using them, so he went to the army to argue for their adoption in place of French horns and bassoons in marching bands. In 1845 the Champ de Mars was the scene of a battle between an army band of forty-five musicians and a band of thirty-eight assembled by Sax, an encounter witnessed by twenty thousand spectators. Sax won the audience’s applause and a military contract. At the exposition of 1849 he received both a gold medal and a medal of the Légion d’Honneur for his new invention, the saxophone.[33]

A public concert is inherently a kind of spectacle, so it is not always easy to determine where musicianship stops and showmanship begins. Paganini made his audience wait for him while he watched from the wings so as to be able to appear just when expectation had reached a peak. While he excoriated the tales of his pact with the devil, he also exploited them. The violinist Ole Bull told of Paganini coming on stage with his long black hair, a black swallow-tail coat, and a small box in his hand:

One of the few things outside of music that made an impression on Paganini was the magic show of Bosco. As for Liszt, according to Heinrich Heine, “no one in the world knows as perfectly as our Franz Liszt how to organize his successes, or rather how to stage them. In this art, he is a true genius, a Philadelphia, a Bosco, a [Robert-]Houdin.” Robert-Houdin described his own art as that of “an actor playing the role of a magician.” According to the newspaper Illustration:He then opened the box and took out a pair of spectacles, meditated a moment, apparently considering the next move, and finally, taking the bow in his right hand, and bending a little, put the spectacles on and looked about in a complacent manner. But how changed he was! The glasses were dark blue, giving a ghastly appearance to his emaciated face; they looked like two large holes in his countenance. Raising his foot and bringing it down promptly, he gave the signal to begin. It had been announced as his last concert in Paris for the season, and a true foreboding seemed to thrill through his listeners that they would not again see that lank, angular figure, with its haggard face, or hear again the wondrous witchery of his violin.

Paganini and Liszt were among the first musicians regularly to give concerts from memory, a common practice today. Their reviewers frequently mentioned it, although there is no inherent relationship between playing from memory and the quality of the playing. But it is always more impressive to see airialists perform without a net. In popularizing the performance of pieces whose chief interest for the audience consists of watching and hearing musicians meet the challenge of their technical difficulties, Paganini with his caprices and G-string solos and Liszt with his own and others’ piano études made perhaps their greatest impact on performance practices. Scheller and Clement and Dreyschock went to such extremes that they could be dismissed, and Mozart could renounce his own youthful excesses, but the showmanship of Paganini and Liszt was so integral to their musicianship and their musicianship was of so high a caliber that despite repeated efforts by some to purge it from the Western classical music performance tradition, and a virtually uninterrupted effort by others to deny its existence there, spectacle survives, even thrives.M. Liszt is not only a pianist, he is above all an actor.…Everything he plays is reflected on his face; one sees depicted in his physiognomy everything that his music expresses and even everything he thinks it expresses. He makes movements appropriate to each piece; he has postures, gestures, and glances for every phrase; he smiles at the graceful passages, and furrows his brow whenever he hits a diminished seventh. All of this is obviously lost for those of his listeners facing his back, so that it is out of a sense of justice and so as not to be unfair to anyone that he employs alternately two pianos facing in opposite directions.[34]

Neither chess nor cooking nor crime-detection is inherently spectacular. Philidor and the Café de la Régence masters made chess spectacular by playing several games at once without looking at any of the chessboards. They did not invent simultaneous blindfold play: Three-game demonstrations given by an Arab visiting Florence in the thirteenth century, by a Syracusan in the sixteenth century, and by an Italian in the early eighteenth century are mentioned in writings of their contemporaries.[35] What Philidor, Labourdonnais, and Kieseritzky did was to translate something eccentric into something central, to make an obscure achievement into a public spectacle and to establish it as a continuous tradition that has persisted for two centuries.

Carême made cooking spectacular by disregarding the old rule that whatever a chef sent to the dining table, with the exception of containers, should be food. He made his four-foot models of classical temples, Gothic towers, Indian pavilions, Chinese pagodas, and Turkish fountains not out of the pastry cook’s traditional pastillage (“paste”) of gum tragacanth, wa-ter, sugar, and powdered starch, which are all edible ingredients, but out of a mastic (cement or putty) of gum arabic, gum tragacanth, water, sugar, powdered starch, calcium carbonate, and marble shavings! “Finally, after having made several experiments in this matter, I succeeded in compounding this mastic, out of which I constructed, nine years ago, two large trophies, which are intact today, and still as splendid as they were on the first day.” [36] Carême’s inedible edifices formed the centerpiece of what amounted to a whole program for making a spectacle out of cooking, which included increasing the number and variety of dishes served in each course, piling up garnishes on top of large roasts and whole fish with the help of hâtelets, and commissioning serving implements with neoclassical ornamentation designed by himself. Carême made his preparations less to sate the stomach than to dilate the eye.

Vidocq, who as a youth had worked for the physicien Comus,[37] strove to make a spectacle out of crime-detection. He preferred to arrest suspects in a crowded tavern, bursting in suddenly with a group of Sûreté agents and shouting orders, than to apprehend them in a less risky but more isolated location. He liked to appear at Bicêtre for the ceremonial chaining of recent convicts at the start of their long march to the galleys, a semiannual event that drew as many as a hundred thousand spectators to this suburb of Paris for a day of edifying Schadenfreude, particularly piquant for Vidocq, since twice in his earlier life he had been among the participants, whom he now took the opportunity to berate publicly. In courtroom trials, Vidocq stole the show from the lawyers, using the witness box as a stage from which to recount his feats as a detective.[38] He finally got his chance to appear on a real stage at the age of seventy when he gave demonstrations of his disguises and other detective apparatus for two seasons at a London exhibition hall. But it was only with the creation of the detective story, out of Vidocq’s career and his account of it in his Mémoires, among other materials, that a largely private activity could be approximated to a spectacle.

The necessity or desirability of appealing to the public led to spectacularism in politics, theater, art, science, technology, automaton-building, musical performance, chess, cooking, crime-detection, and many other social activities. Spectacularism involved emphasizing those aspects of an activity that had intrinsic immediate eye- or ear-appeal or adding extrinsic features to an activity to give it that appeal. An institution specifically designed for appeals to the public—that is, for publicity—already existed. Not surprisingly, the prodigious progress of publicization and spectacularism was accompanied by a commensurate development of the press, a development that can only be described as spectacular.