3.

Promoters and Seers I: Antonio Amundarain and Carmen Medina

Mary's sorrowful opposition to the Second Republic was the central interest of believers and seers at the Ezkioga visions in the summer of 1931. Press and public nudged along the evolving political message in a collective fashion. Simultaneously, another process, less collective, ensured that the seers produced messages for particular constituencies. Socially powerful organizers sought divine backing for various programs. After the summer of 1931 their projects absorbed much of the seers' attention.

In early August 1931, in the absence of a confirming miracle, the people of San Sebastián and Bilbao and their newspapers got over their first, sharp interest in the visions. Reporters tired of the same seers and the same messages. In any event the seers lost their forum. For the government, fearing a rightist military uprising, suspended most newspapers in the north on August 22. El Día, which printed the most about Ezkioga, only came out again at the end of October.[1]

La Constancia resumed publication on September 22 and El Día on October 25.

By then the tide had turned against the visions. After early August there was little detailed reporting of the visions and visionaries.This decline in publicity coincided with the Radical Socialist Antonio de la Villa's attack on the visions in parliament and military exercises in the area. For whatever reason, the visionaries subsequently shied away from overt political messages.

Diaries, letters, books, and circulars by literate believers are our main sources for the following months and years. They show the extent to which the visions, like those at Limpias a decade earlier, served as a sounding board for movements and new devotions within Spanish Catholicism. This is not surprising. Catholics came to Ezkioga from all of Spain and southern France, many of them with prior agendas. A large number of visionaries continued to provide messages of great variety. Many seers were open to suggestion. Highly literate emissaries from the urban world of devotional politics latched onto particular rural visionaries or were actively sought out by them. This kind of symbiosis points us toward the mystical side of these Catholic movements and to principles governing alliances across boundaries of class, gender, age, and culture.[2]

For Limpias see Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 82-118.

The next three chapters recount the principal alliances of promoters and seers. Pressure from the increasingly hostile diocese, counsel from spiritual directors, and rivalry among seers and among promoters affected these alliances. Seers attempted to convince observers. Observers had to decide whom to believe. Or, if observers believed in several, they had to decide who had the most important messages. Those believers who sought to influence or to gain inside information from seers had to win them in some way. Believers drove the most convincing seers to the site, gave them gifts, and spread their vision messages. Over time, as these seers gained an ample public, they tended to address issues that were more general—at first political and later apocalyptic. Coming from the most convincing seers, such dramatic messages more easily passed the severe scrutiny they provoked. At the other end of the spectrum, the less theatrical, less convincing visionaries nonetheless each had a band of followers (called a cuadrilla ) which principally included persons who had known the seer previously—friends, family members, and neighbors—and who therefore trusted the seer. These less virtuosic visionaries spent more time attending to the spiritual and practical needs of constituents with less ideological interests.

As the popularity of the visions as a whole rose or fell, individual seers might move from one mode of response to another. A number of seers, when they started, addressed personal questions. When they became more popular, they supplied a more general public with news about political developments and the Last Judgment. If the visions then lost favor and only die-hard supporters remained, the seers responded once again to believers' personal needs.

Such relationships between seers and critical believers have affected the lives and work of virtually all Catholic mystics who achieved fame, for what is at stake is fame itself. Promoters are critically important for seers whose access to literate, urban culture can only be achieved through others. We know the nobleman

Francis of Assisi primarily through the eyes of those around him. We depend even more on chroniclers and promoters to learn about the day laborer Marcelina Mendívil of Zegama. As we look at particular learned believers and their contacts with particular seers, we gradually become aware of a far more general process by which the parties creatively combine suggestion and inspiration. As they court and separate, promoters like Antonio Amundarain, Carmen Medina, Manuel Irurita, Magdalena Aulina, Padre Burguera, Raymond de Rigné and their seers show us one way societies create new religious meaning.[3]

On St. Francis see Kleinberg, Prophets.

Antonio Amundarain

The first, crucial link between visionaries and influential believers was between the girl from Ezkioga who was the first seer and the parish priest of Zumarraga, Antonio Amundarain Garmendia. Apparitions with a broad public appeal can be halted with ease only at the very start. The parish priest, usually the first authority to deal with the matter, is of utmost importance. If he is indecisive or reacts positively, the visions can build up momentum before newspapers and diocesan officials notice them. So it was fortunate for the Ezkioga visions that the girl seer found her way to Amundarain, a clergyman influential in the diocese and fascinated by mystical experiences. The parish priest of Ezkioga and the curate in charge of Santa Lucía were far less famous and far more hardheaded.[4]

For the critical role of the parish priest at Oliveto Citra (a vision site in southern Italy) see Apolito, Dice, 1-175 and 57: "Tutto evidentemente si gioca nei primissimi giorni."

Amundarain heard about the Ezkioga visions from the woman who brought him milk. Antonia Etxezarreta, then twenty-three years old, had found out from Primitiva Aramburu, who brought milk from the farmhouse nearest the site of the visions. Primitiva had heard about them from her sister Felipa, who had been with the girl and her brother when they had their first vision.[*] Antonia was a curious, lettered woman who contributed reports in Basque to Argia . She stopped by the school in Santa Lucía to talk to the seer girl and then took her with mule and milk to Zumarraga. At the rectory she presented the girl to a curate she trusted and liked. He was inclined to dismiss the matter, but it was Amundarain who was in charge. The next day, July 2, when Antonia brought the milk, Amundarain had her tell him what had happened and that evening he went to observe the visions.[5]

Antonia Etxezarreta, Ezkioga, 1 June 1984 and 6 February 1986; Etxezarreta, Eup! April 1994; and Felipa Aramburu, Zumarraga, 7 February and 14 May 1986.

Amundarain's past and character are vital to this tale. They explain why he did not dismiss the visions but instead nursed them into a mass phenomenon in the first week. A priest with intense energy and drive, Amundarain was a born organizer who was also a photographer, musician, and author of religious dramas. In Zumarraga he supervised six clergymen and three houses of nuns. He

As in the case of other seers who are or who may be alive at the time of this writing, I do not refer to the original brother and sister by name.

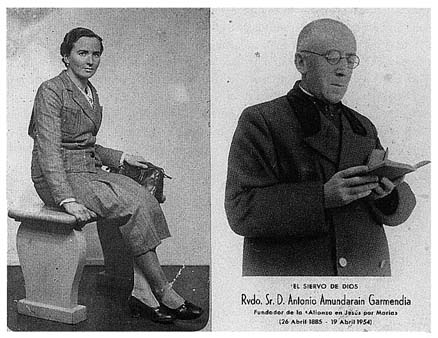

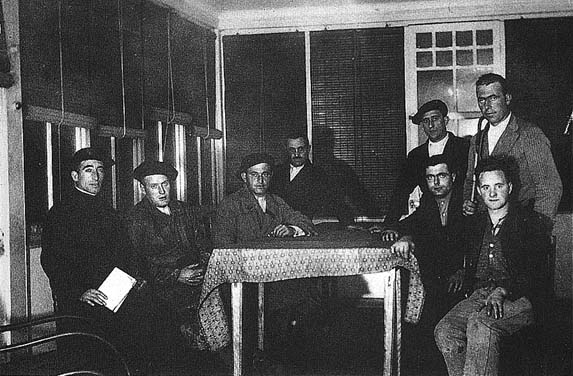

Left: Antonia Etxezarreta, the milkmaid who connected the first seer with Antonio Amundarain.

Photo ca. 1931. Courtesy Antonia Etxezarreta. Right: Antonio Amundarain Garmendia, 1948

came from the rural town of Elduain, and his father had been a Carlist soldier in the Carlist War half a century earlier. Amundarain's mother had bad memories of the Liberal household in which she had worked in San Sebastián, and her son had no yearning for the easy life of the city. One of his brothers was a Franciscan missionary in South America, a nephew became a priest, and two nieces were nuns. Amundarain himself was a Carlist-Integrist. He received La Constancia, La Gaceta del Norte , and Euzkadi . Occasionally he contributed to Argia and La Constancia . He considered La Voz de Guipúzcoa sinful. He read standing up so as not to enjoy the activity too much or waste time.[6]

Juan María Amundarain Legorburu (Amundarain's nephew), San Sebastián, 3 June 1984. Antonio Amundarain and the priests of his movement were opposed to the subsequent Basque Nationalist alliance with the Republic. In the 1980s this fact colored the attitude toward him of many men in Zumarraga and of the many priests sympathetic to the Nationalist cause.

Amundarain's first post had been as chaplain to the Mercedarian Sisters of Charity in Zumarraga from 1911 to 1919 and directing female religious remained his true calling. In San Sebastián, where from 1919 to 1929 he was a curate, he served as confessor to several communities of nuns.[7]

Pérez Ormazábal, Aquel monaguillo, 73.

There in 1925 he founded the Alliance in Jesus through Mary (La Alianza en Jesús por Maria), a lay order in which young women and older teenage girls took temporary vows of chastity and poverty, followed a rigorous dress code, and helped in parishes. By 1929 there were 207 Alliance members (Aliadas ) in twenty chapters in Gipuzkoa, Alava, Bilbao, and Madrid. By then an eighth of the young womenhad gone on to become nuns. The Mercedarian Sisters came to know the Aliadas well; numerous Aliadas joined the order and the sisters helped to set up Aliada centers in the towns where they had houses.[8]

LIS 50 (September 1932): 246-261. Amundarain eventually wrote a history of the order. He was also favorable to the installation of the Passionists, Artola, Martín Elorza, 37 n. 3.

In the next two years the lay order quintupled in size, spreading to most Spanish regions. In the Basque Country Aliadas were established mainly in the provincial capitals, but there were centers in six other towns, including Zumarraga. Each section had a local spiritual director, so in 1931 Amundarain had a network of priests with whom he was in close contact. At that time the Basque Aliadas were largely from kaleak , the town centers. In the eyes of the farm people they were "señoritas [young ladies]," and I have the impression that in more rural areas many were sisters of priests. For all of the Aliadas Amundarain was a charismatic figure.[9]

LIS 17 (February 1929): 6; LIS 50 (September 1932): 238-239. Basque Aliadas: San Sebastián (174), Eibar (44), Zumarraga (34), Pasaia (34), Zumaia (33), Mondragón (21), Bilbao (125), Baracaldo (41), Vitoria (156).

With this order Amundarain worked to preserve women frrom corupt modern society, especially its sexual side. And he tried to ensure that these women at least would not make modern society more corrupt. Some women have told me that in those years in the confessional he concentrated heavily on the sins of impurity. And in this sense the Alianza was an extreme expression of a reigning preoccupation.[10]

Amundarain, LIS 19 (May-June 1929): 57; Sobrino, Amundarain, 275-291.

Members kept close count of their rosaries, Our Fathers, masses, novenas, and mortifications, and Amundarain reported the totals in the journal Lilium inter Spinas . While the idea of an order of devout laywomen working in the world was unusual for the 1920s, it was not new in Spain. Prior to the Council of Trent women known as beatas had taken temporary vows and many had led lives in contact with the world. In 1926, however, Amundarain's concept of a lay institute was new again. Two years later, in 1928, José María Eserivá y Balaguer founded another lay institute, Opus Dei.Even for his time, Amundarain's religion was stern and rigorous. This was the Catholicism of the amulets of the Sacred Heart of Jesus which read, "Detente Enemigo [Stop Enemy]." This was a Catholicism wounded and angered by the anticlericalism in much of Spain. Yet this was also a Catholicism bound to the profane world it opposed. In San Sebastián in 1921 Amundarain instituted weekly prayer meetings on Friday afternoons during the summer as atonement for the sins on the nearby beach, and this session became a fixture of the Aliadas. The Aliadas themselves were a defense against the enemy of God. As Amundarain wrote in early 1931, the Alianza was an army of virgins, "of victim souls, a host of love, an oasis of purity, a legion of chaste Judiths and valiant Jeannes d'Arc." Their goal was to "placate" and "discharge the wrath of God" in the face of "irreligion, libertinism, immorality, corruption," and "pillage, anarchy, atheism, and destruction." All this took place, he wrote, on "the eve of a worldwide cataclysm."[11]

Pérez Ormazábal, Aquel monaguillo, 83-84; Amundarain, LIS 6 (January-February 1931): 9-10.

Mateo Múgica, bishop of Vitoria, shared this strict Catholicism. We see him posed in photographs with the Aliadas. The strategy of Múgica, Amundarain, and many of their peers was essentially defensive. They retreated to the high

ground of rural religiosity and the protected zones of the upper class and defended them tooth and nail from the surrounding world. They considered the urban working class almost irredeemably lost. For Amundarain only supernatural help could soften the hardened heart and regain those lost to the church.

To maintain and deepen the faith of practicing Catholics, Amundarain placed great value in the spiritual exercises of Ignacio de Loyola. These were a directed series of prayers and meditations with vivid use of the imagination to draw people out of the everyday world and focus their minds and emotions on the life, passion, and resurrection of Christ. He himself performed the exercises annually. In 1928 he organized them for 700 girls in San Sebastián. When he went to Zumarraga in 1930, he held them first for 300 teenage girls, then for 150 boys, and in early 1931 for adult men and women. No parish priest in the diocese made more energetic use of the exercises at this time; at least no one else published the statistics in the diocesan bulletin. When Amundarain brought parishioners to the Ezkioga visions, they were well prepared in spiritual imagination.[12]

BOOV, 1930, p. 372; Pérez Ormazábal, Aquel monaguillo, 93-108.

Amundarain also promoted local shrines. A devotee of the Virgin of Aranzazu and a leader of pilgrimages to Lourdes, in Zumarraga he composed a hymn to the local devotion of Our Lady of Antigua and began an annual novena at her ancient shrine above the town. In June 1931 he dedicated the novena to atonement for the burning of religious houses, and an Aliada present remembers him saying when they came to the Litany, "Now, with great devotion, put your arms in the form of the cross." He also started an annual mountaintop rosary on May 1 at the iron cross of Beloki above the town; nine meters tall, the cross was lit on the nights of special feasts.[13]

Sobrino, Amundarain, 86. The cross was erected 1 May 1900 and again in 1926; for the cross in 1932 see La Cruz, 24 April; LC, 27 April, p. 8; and A, 12 May, p. 1.

Amundarain's collaborator and biographer, Antonio María Pérez Ormazábal, referred to him as "excessively credulous—as credulous as he was pious." In the 1920s in San Sebastián, says Pérez Ormazábal, Amundarain was "the paladin of all the movements of a spiritual and supernatural nature that emerged at the time." When the Mercedarians completed their convent chapel in 1929 under his supervision, they installed a bust of the Christ of Limpias. In early 1931 he published in the Alianza journal excerpts of a message from a French mystic nun. In 1932 we find Amundarain passing out the first Spanish pamphlet about the apparitions of Fatima. And he was a devotee of Madre Marí Rafols of Zaragoza and gave his nephew a picture of her as a talisman in the Civil War.[14]

On Amundarain's credulity see Pérez Ormazábal, Aquel monaguillo, 110; Pérez Ormazábal, Así fue, 83; on Limpias see Amundarain, Vida congregación mercedarias, 329; on Fatima see Salvador Cardús to the Piarist Rimblas, 21 April 1932; on Rafols see Juan María Amundarain, San Sebastián, 23 June 1984; on the French mystic nun, Sulamitis, see Amundarain, LIS 35 (June 1931): 1-11.

I learned much about Amundarain from this nephew, Juan Marí, who grew up with Amundarain in Zumarraga. Juan María's sister Teresa was an Aliada and Amundarain's favorite. Juan María was one of the last weavers of wicker furniture in Gipuzkoa, and I talked with him as he worked in a cool, dark loft in the old quarter of San Sebastián. There he sang "Izar bat [A Star]," a hymn

composed for the Ezkioga visions. That year a church commission considering the beatification of his uncle had interviewed him for three days. One sticking point for the commission was precisely Antonio Amundarain's enthusiasm for the visions.[15]

The beatification proceedings opened 27 November 1982.

Other priests, family members, friends, and the people of Zumarraga describe Amundarain as righteous, rigid, discreet, and extremely pious. He traveled throughout the diocese to give sermons and was famous as an effective confessor. By 1931 he was a leader among the clergy who knew how to act with energy and authority. In the absence of Bishop Múgica, known to be his friend, he organized and supervised the Ezkioga visions in the first months. His presence gave the visions a credibility and legitimacy they would otherwise have lacked.

We can follow much of Amundarain's involvement at Ezkioga in the press. He took the first seers to find the exact spot where the Virgin appeared, led the rosary, managed the news that reached the crowd, confided to a reporter his hope for a miracle, and retained the children's declarations in written form. On July 28, a month after the first visions, he instructed the public, through the newspapers, how to behave at the site, as if the Ezkioga hillside was his parish church. This note provoked a public rebuke from the diocese. Thereafter Amundarain kept a lower profile and let his subordinates lead the vision prayers.[16]

All 1931: LC, 7 and 9 July; GN, 17 July; PV, 18 July; ED and LC, 28 July.

In correspondence and in the Alianza journal Amundarain revealed some of his more private thoughts and hopes about the visions. On July 6 he wrote to María Ozores, head of the Aliadas in Vitoria: "Soon you will all find out about alarming prodigies that we are witnessing here these days. Tell the sisters to pray a lot …" To an ally in Vitoria he wrote on July 25: "The Ezquioga affair is something sublime, the most solemn act of atonement that Spain now offers to God. The Virgin cannot abandon us." On September 13 he took three hundred Aliadas to Ezkioga in a heavy rain "to pray for the Alianza … the church … the bishop in exile, for our poor Spain, and for everyone." "Two little virgins in ecstasy" had visions while the Aliadas prayed and sang. One seer told the Aliadas afterward:

The Virgin was down close. I have never seen her so low, almost touching the ground and in the midst of the Sisters. She wore her black mantle very loose, and let her white interior tunic be seen, tied at the waist with a white cord, and showing the tips of her bare feet, and with a very pleasant and happy expression on her lovely face, and with a very sweet voice she spoke … and said that she was very pleased with the Alianza, and that the Sisters have much, much confidence in her, and her powerful protection will guard the Obra.

It is possible that one of these seers was Ramona Olazábal, but by September a number of seers delivered this kind of tailor-made message.[17]

Amundarain to Ozores, Zumarraga, 6 July 1931, and to A. Pérez Ormazábal, 25 July 1931, AAJM. I thank the then director general of the Alianza, Andrea Marcos, for her help. For September pilgrimage see Amundarain, LIS 39 (October 1931): 24-27. To this message he added, "Can this be true, my little Sisters?"

Amundarain believed the first seers. He then turned to others, like Ramona. Why was he so soon distracted? Let us look at the seers.

The First Seers

The sister was born in 1920, the brother in 1924. (In this account they shall remain anonymous.) When they had their first vision she was eleven and he was seven years old. Their father had a small roadside bar and they lived upstairs with their four brothers and sisters. The girl was quiet and introverted. The Irish traveler Walter Starkie wrote, "I have rarely seen such a tragic expression on a child's face. She looked as if she had already borne the brunt of a whole life's sorrow." When Starkie was at Ezkioga at the end of July, he noted that "she had stopped seeing the Virgin, and she shut herself up in her room and refused to play with the other children." In all, the girl had sixteen visions. She never fell into a trance when doing so, she remained impassive, and her pulse did not vary. She never heard the Virgin speak.[18]

S 127.

Her brother was more lively. Starkie described him as mischievous and impudent. Newspapers reported him as "unruly," "brusque," "alert," "smart," and "simpático." After the visions were discredited, they called him "bold," "brazeen," and "wild." The Ezkioga parish priest wrote, "The boy is pure rebellion." According to some reports he did not speak Spanish. A San Sebastián writer commented at the beginning of August: "He is a terrible rebel, and by now he is used to the vision and does not attribute it the least importance, and he is sick of being questioned."[19]

S 126; for Ezkioga priest see L 24; the San Sebastián writer, Lassalle in PN, 6 August 1931.

The boy rarely fell into anything like a trance. He would simply stop playing, extend his arms and pray during his vision, then go back to playing. He might climb trees as people prayed on the hillside or run off into the woods when people wanted to talk to him. His visions occurred in various places, especially in apple trees behind his house. He did not hear the Virgin speak. By early September he had had thirty-one visions and believers claimed that he continued having them daily for at least two years. In early 1934 he had them during family prayers at night. By then he went to school in Zumarraga.[20]

Delás, CC, 20 September 1931; R 8; EE 2 (February-March 1934): 6; Rigné, Ciel ouvert, p. C.

An older neighbor followed the events closely from 1931 to the present. She told me that this family "was very simple, the simplest family around here, so modest and humble. They never liked to stand out. A family always unassuming."[21]

Antonia Etxezarreta, Ezkioga, 1 June 1984, p. 16.

And despite snide allusions to the contrary in the press, the family and seers profited little if at all from the visions. Older Ezkioga residents distinguish the sister and brother from the later, more famous seers and emphasize the children's innocence and lack of ulterior motives. They feel that older seers "messed it up." But people hungry for answers to religious and political questions and aching personal problems could hardly rest happy with the sister and brother,especially while other, more theatrical and more attractive seers were delivering the desired goods.

For others were hearing messages from the Virgin and providing answers to the public. The voluble seers, not the silent ones, led Amundarain and many others to expect a great miracle in mid-October. Two seers in particular convinced him. One was an Aliada from San Sebastián who had had visions at Ezkioga. She had another on about 6 October 1931. In "a pleasant conversation," the Virgin told her, as Amundarain reported to a colleague,

that within a few days there will be a prodigy (in this she coincides with the visionary of Ataun) and three times She insisted to her that all the Sisters be that day at Ezquioga, and each one with her emblem on display; that the Alianza has been called to save many souls in the world.[22]

Amundarain to A. Pérez Ormazábal, Zumarraga, 10 October 1931, AAJM.

An even better reason to expect a portent on October 15 was a semiprivate prophecy by Ramona Olazábal.

Ramona Olazábal, the Girl with the Bleeding Hands

Ramona Olazábal was fifteen when she had her first vision on July 16 at Ezkioga. Born and raised on an isolated farm in Beizama, about twenty kilometers away, she was one of nine surviving children. Before the visions she stood out for her vivacity and her fine dancing more than her piety. At age nine she had gone to live with her sister in Hernani, and by age thirteen she was working in aristocratic households in San Sebastián. When she began to have visions in July 1931 she had spent much time away from the farm and had had some contact with the upper classes.[23]

R 8 gives Ramona's birthdate as 13 August 1915; PV, 18 October 1931, p. 5; Juan de Urumea, El Nervión, 22 October 1931; R 11.

Like other visionaries in July, Ramona wanted to know if there would be a miracle and when it would be. By the end of the month, she was "one of the best known seers," for newspapers had reported nine of her visions. At the beginning of September a Catalan pilgrim wrote that "her prayer consists of an insistent clamor for pardon and mercy for everyone" and that of the seers she was "the only one who sees the Virgin as happy."[24]

All 1931: LC, 17 July, p. 2; ED, 18 July, p. 12; and 31 July, p. 7. Also reports in ED, 24 and 26 July, and PV, 24 July. Delás, CC, 20 September 1931.

About this time Ramona stopped working and moved to Zumarraga, closer to the vision site. There she stayed with her cousin Juan Bautista Otaegui, one of Amundarain's curates, who boarded in the house of Amundarain's brother. She had many followers and for some she provided special messages. Amundarain's niece, the Aliada Teresa, often accompanied Ramona shopping, for Ramona had money from believers. Ramona gave a sealed letter to Otaegui saying that on October 15 the Virgin would give her a rosary. Amundarain took the prediction seriously, no doubt because it coincided with the visions of the San Sebastián Aliada. Ramona sent a similar letter to a prominent family in San Sebastián. And on October 13 and 14 she told many people to bring handkerchiefs, for the Virgin was going to wound her.[25]

On Ramona's shopping see Juan María Amundarain, San Sebastián, 3 June 1984, p. 3. Otaegui was certain the miracle would occur, according to Pío Montoya, San Sebastián, 7 April 1983; B 212. Ramona informed the San Sebastián family of Luis Zulueta, a Republican deputy in the Cortes on good terms with Múgica and Echeguren: LC, 17 October 1931, p. 2, and 17 May 1932, p. 1.

On October 14 Amundarain wrote to the Aliada leader María Ozores in Vitoria: "It seems the Virgin is calling you here; we are in historic days, and we have to give heaven strength." He assigned Ozores and another Aliada to stay with Ramona the next day and search her before she went up the hill. Amundarain had a family lunch to celebrate the saint's day of his mother, and then he, his brother, and his nephew went to the apparition site.[26]

Amundarain to Ozores, Zumarraga, 14 October 1931, AAJM; one of the Aliadas, María Angeles Montoya, San Sebastián, 28 April 1984, p. 7, who was with Dolores Ayestarán, the sister of a priest who worked with Amundarain; for family lunch: Juan María Amundarain, San Sebastián, 3 June 1984, p. 4.

After the Aliadas searched her, Ramona went into an outhouse before going up the hillside. Fifteen to twenty thousand persons, the largest crowd since July 18, had been attracted by the predictions she and Patxi Goicoechea had made about a miracle. Ramona emerged at about 5:15 P.M. with her close friend, a girl from Ataun who was also a seer. When Ramona neared the fenced area for visionaries, she lifted her hands. Blood spurted from the backs of both. "Odola! Odola! [Blood! Blood!]" shouted the crowd. Men carried Ramona into the enclosure, and there a doctor found a rosary twisted around the belt of her dress. In an atmosphere of awe and anguish men carried her downhill seated in a chair, like an image in a procession. All the time people collected her blood on their handkerchiefs. Alerted by phone, pilgrims poured in from all over the Basque Country well into the night.[27]

R 17-18; L 13. See SC E 83-94 for eyewitness. News on 16 October 1931 in PV (San Sebastián), PV (Bilbao), DN, Easo, and LC, and on 17 October 1931 in PV, VN; for excitement that night: Casilda Arcelus, Ormaiztegi, 9 September 1983, p. 3.

The Aliadas Amundarain had detailed to observe Ramona were totally convinced. When María Angeles Montoya arrived at her home in Alegia, she told her brother Pío that a miracle had happened. Pío, a priest who was cofounder of El Día , immediately called Justo de Echeguren, the vicar general of the diocese and an intimate family friend. Pío emphasized that unless Echeguren investigated Ramona's wounding at once there would be no stopping the matter.[28]

For Echeguren's involvement: Pío Montoya, San Sebastián, 7 April 1983, pp. 4-8.

The next morning Echeguren arrived by train at Zumarraga, where he met Montoya, Amundarain, and Julián Ayestarán, a priest who worked with Amundarain on the Aliadas and whose sister had watched Ramona the day before. Amundarain reported what had happened and spoke favorably about the innocence of the original seers. Echeguren was skeptical about the miracle, but the fact that María Angeles Montoya, who was like a niece to him, believed in it gave him pause. So he immediately formed an ecclesiastical tribunal consisting of himself, Montoya, and Ayestarán to interview witnesses.[29]

Montoya's detailed recollection of the hearing coincides with what Echeguren wrote José Antonio Laburu, Vitoria, 13 April 1932.

Before starting the proceedings, Echeguren had in hand the letter that Ramona had given her cousin Otaegui. He also talked to a man whom Ramona had told to bring a handkerchief and to her friend from Ataun, whom Ramona had told she would receive stigmata. He then asked Ramona whether she had told anyone about what would happen. She denied three times that she told anyone, and Echeguren became so angry that he broke his pencil. He confronted her with the conflicting evidence, including the letter, and she admitted that she had indeed told people and named still others. He told her she had been lying and sent her off.

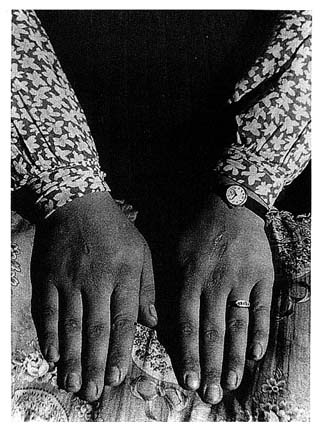

Crowd at Ezkioga, mid-October 1931

At that point a man from Lezo asked to speak to Echeguren in private. He said that the day before he had been next to Ramona when, stunned by seeing the blood coming out of her hands, he had lowered his eyes in awe and seen to his surprise a razor blade on the ground. He had come back to look for it. To settle the matter, Echeguren asked Montoya to find two doctors, one Catholic and the other, if possible, a non-Catholic, to examine Ramona's wounds. Montoya called in Doroteo Ciaurruz, later the Basque Nationalist mayor of Tolosa, and Luis Azcue from the same city and both examined Ramona that afternoon. That night they reported to Echeguren at Montoya's house that they thought Ramona had inflicted the wounds on herself, most probably with a razor blade. Echeguren immediately drew up a note for the press that said there was positive evidence of natural, not supernatural, causes for Ramona's wounds.

At some time in the fall of 1931 Echeguren instructed priests not to lead the rosary at the site and, according to one source, reprimanded Amundarain for his involvement in the apparitions. On November 4 Amundarain sadly wrote to María Ozores:

Ezquioga continues to wind down. New prophecies of something extraordinary, new dates, new preparations, new failures. I continue to believe in a

Scars on Ramona Olazábal's hands, late October 1931.

Photo by Raymond de Rigné, all rights reserved

powerful, extraordinary intervention and presence in these mountains of Our Mother, but among the seers there is a lot to be purged.[30]

Amundarain to Ozores, Zumarraga, 4 November 1931, AAJM.

I find no more reports of Amundarain at Ezkioga. But he continued to hear the effects of the visions in the confessional. On December 14 a group of Catalan believers visited him. One of them wrote:

The parish priest of Zumárraga spoke to us of the beautiful spiritual fruit harvested at Ezquioga. There have been countless general confessions, he told us, and they still continue. Even today, he added, there were some in this church. Even men eighty years old have wanted to make a general confession.

He said he believed 80 percent of the seers, but that Freemasons had become involved to discredit the apparitions. By this time both he and Otaegui had broken with Ramona.[31]

Gratacós, "Lo de Esquioga," 14-16. ARB 9-10 also mentions the visit. Suspicion of Freemason plots to make the church look ridiculous may derive from the Leo Taxil affair, in which an anticlerical freethinker feigned conversion to Catholicism, got church leaders to believe preposterous stories, and then revealed the hoax (Ferrer Benimeli, El Contubernio).

A year later, on 16 December 1932, due to stress and ill health, Amundarain resigned as parish priest to devote himself fully to the Alianza, which he did for

the rest of his life. But he did not renounce his hopes for Marian apparitions or his hopes for the role the Aliadas would play. In his copy of a book of prophecies published in 1932, the following passage from the prophecy of Madeleine Porsat is underlined and "¿Alianza?" written in the margin:

The church is preparing everything for the glorious coming of Mary…. It forms a guard of honor to go out and meet the angels that come with her.

The arch of triumph has been erected. The hour is not distant.

It is she herself in person, but she has her precursors, holy women and apostles, who will heal the wounds of the body and the sins of the heart.[32]

Sobrino, Amundarain, 93-94. Echeverría Larrain, Predicciones, 62. Amundarain loaned his copy to a fellow priest, Juan Ayerbe, whose niece kindly showed it to me. See also below, chap. 14, "The End of the World."

Antonio Amundarain was prudent in public about the visions. As far as I know, he had little personal contact with the seers, but his sharp attention, foresight, and careful use of the media were critical to the pace and momentum of the visions. Many people thought he was acting on behalf of the diocese. El Pueblo Vasco reported that "it was [Amundarain] who was charged by Vitoria to gather testimony of the events." If this was the case, Amundarain's role would have been unofficial. Such a procedure was not unusual. Both at Limpias and at Piedramillera bishops instructed the parish priests to take down testimony of seers as if at their own initiative. When Amundarain issued the note on July 28 referring to the commission of priests and doctors as "official," the vicar general immediately issued a denial, disavowing any diocesan connection. Given the vicar general's subsequent total skepticism, it would seem that Amundarain was on thin ice from the start. But at least in some matters he seems to have worked for Echeguren. That Amundarain had matters in hand probably contributed to the diocese's relaxed attitude in the first months.[33]

EZ and PV of 18 July 1931; Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 52, 126; ED and PV, 29 July 1931; Echeguren wrote to Rigné, 22 December 1932 (typed copy in private archive), that it was on his instructions that the Aliadas watched Ramona on the day of the miracle. Amundarain may have told him about Ramona's letter, and he must have let Amundarain choose the women.

Carmen Medina y Garvey

Amundarain's cool distance contrasts with the active engagement of most of the other key believers at Ezkioga, including the second leader to arrive on the scene, Carmen Medina y Garvey, whose close contacts with seers—including Lolita Núñez, the girl from Ataun, Patxi Goicoechea, and Evarista Galdós—lasted for at least three years.

At the Casa de Pilatos in Seville I learned about Carmen from her nephew, Rafael Medina y Vilallonga, the former mayor of the city.[34]

Sevilla, 23 October 1989; Medina, Memorias.

He estimated that Carmen was about sixty years old in 1931. One of the ten children of the marquis of Esquivel and Dolores Garvey, she was very wealthy, for she inherited land from her father and money from the sherry fortune of her bachelor uncle, José Garvey. She became a nun in the convent of the Irlandesas in Seville, which she helped to restore with her money. She later left this convent and founded another of her own, but the new convent apparently did not survive.

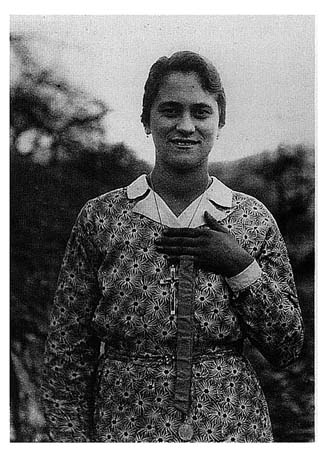

Carmen Medina at the base of the Ezkioga hill before an automobile with diplomatic plates

and the stand of the photographer Joaquín Sicart, 1932 or 1933. Photo by Joaquín Sicart

Two of Carmen's sisters became nuns and a sister-in-law entered a convent when widowed. Carmen's sister María Josefa and her brother Luis married, respectively, the son and daughter of the couple, Rafaela Ibarra and José Vilallonga. In 1894 Rafaela Ibarra founded an order, the Instituto de los Santos Angeles Custodios, dedicated to the care of young women in danger of becoming prostitutes. Indeed, Rafaela has been beatified, and when I asked to speak to the family about a relative involved in religious visions, they thought I referred to her. José Vilallonga was the founder in Bilbao of Spain's biggest iron works. In the early twentieth century the alliance of Andalusian aristocrats with Basque industrialists was not unusual. The women of both families in this particular alliance had enduring religious interests and a social conscience. Carmen had other powerful relations, including the leader of the monarchist Unión Patriótica, who was the minister of public works under Primo de Rivera.

Carmen Medina's nephew and niece remember her as loving, high-spirited, and generous, but they were somewhat wary of talking about her, for they also thought her a little unstable and feared her enthusiasms might reflect badly on the family. It was my understanding, although this was left rather vague, that

she herself had had visions at some time in her life. The family, I gathered, thought of her as a beloved, credulous eccentric. They remember, for instance, when she announced to her nieces in San Sebastián that on a certain day a tidal wave would wipe out the city. She had learned this from a male seer, who had it from the Virgin. When the tidal wave failed to materialize, she went back to the seer, who told her (and she told her nieces) that when he saw the Virgin again, he noticed a tail sticking out from under her mantle and recognized the devil in disguise.[35]

Carmen Medina had over fifty nieces and nephews and provided them with swimming pools and tennis courts. On 18 March 1932 Luis Irurzun had a vision of the sea wiping out San Sebastián (B 657).

In late July Walter Starkie found Medina already ensconced in an Ezkioga fonda with two female companions.

Doña Carmen, in the intervals of putting Gargantuan morsels into her mouth, pontificated about everything. She apostrophized the girls who were serving the dinner; she abused the cook; she asked for the priests; she criticized the behavior of some of the young people at the religious service: her resonant voice echoed and reechoed through the house. I tried to crouch in my corner, but I knew that sooner or later I should be dragged within her sphere of influence and become a butt for her inquisitive questioning.

… she was one of those imperious women who declare their views but never wait for an answer. Such people's whole life is so rooted in assertion, that they only hear their own voices. Destiny fortunately deafens them to any other sound.[36]

S 121-122.

Medina assumed that Starkie was a pious Irish pilgrim, so she made no secret of her politics. She told him the Republic was a force of Satan.

Though [Carmen Medina] was a daily communicant and spent a great deal of the day in prayer, she was a very active and practical woman, and directed many organizations connected with the church and the exiled monarchy…. The Basque province and Navarra, in her opinion, would rise before long in defence of their religion. In my own mind I felt quite convinced that she was doing her best to use the Ezquioga apparitions as a political lever…. "Our Lady is appearing in order to inspire people to defend their religion. And I tell you that in many cases she is appearing, holding a sword dripping with blood."[37]

S 124-125.

Starkie saw a kind side as well. Carmen Medina was generous with the poor and spoke easily to everyone she met. But:

she was a fighter … she should have been fighting Moors at Granada and raising the Silver Cross above the minarets of the Prophet…. She longed for battle, and I saw her nostrils dilate like those of a war-horse when she described how civil war might come in a few weeks, with the Basques as the leaders of the revindication of the Church of Rome.

Carmen's family had a tradition of rebellion against liberal governments. Her paternal grandfather was a Carlist general. Her father, Francisco, and an uncle participated in the Carlist rebellion of 1873 and as a result her family spent two

years in exile in Portugal. From "Casa Blanca," the home in Seville of Carmen's widowed sister, General José Sanjurjo attempted to launch a monarchist coup in August 1932. One of Carmen's nephews was an active participant, and one of her brothers had to take refuge in France.[38]

For the Carlist past see the biography of Carmen's sister, Padron de Superioras, 17-18. For the Sanjurjo affair see S 125; Esteban Infantes, La Sublevación; Arrarás, Segunda República, 1:505-515; and Rafael Medina, Memorias, 131-135. For arrest of her brother Luis see VG, 19 November 1932.

María Dolores (Lolita) Núñez

Doña Carmen knew the original child seers and introduced them to Starkie, but by that time her interest, like that of Amundarain, had shifted to those who could provide messages. Her first great interest was in María Dolores Núñez, known as Lolita. Medina took Starkie in her car to pick up the eighteen-year-old seer and take her to the vision site.

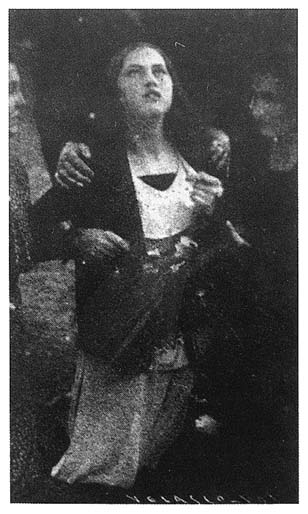

Núñez was educated and refined; according to Starkie, she and her family were "poor members of the bourgeois class" who lived in a small second-floor apartment on the main street of Tolosa. By the time Starkie met her at the end of July, she had had seven visions and her name had appeared in print a dozen times. Her blurry and poignant photograph in El Pueblo Vasco was the first of a seer in vision. She would cry out to the Virgin to save Spain—it was probably this aspect that attracted Carmen Medina—and afterward she would report the Virgin's reaction.

The visions exhausted Lolita, but the excitement prevented her from sleeping at night. She told a reporter, "There is no human force that could resist so much magnificence and splendor. One feels a thousand times more blinded than when one looks at the sun." Her mother and older sister worried for her and opposed her visits to the site. One night in the room where the seers recovered Lolita declared, "Our Lady has told me that I must come here the next seven days, and I must depart from here and sing for joy in the streets." Starkie was disenchanted when Lolita came down to dinner afterward: "She had dwindled again to the fair typist with a good dose of coquettishness and pose" who confided that she had a boyfriend who knew nothing about the visions. Starkie played his violin for her that night and left early the next morning. Lolita's name appeared no more in the press after July 31; no one made postcards of her. If she returned the seven times the Virgin requested, I find no record, nor, alas, do I know if she sang in the streets. Her name meant nothing to the old-time believers left in Tolosa in the 1980s.[39]

PV, 14 July 1931, p. 7; S 141-142, 145-150.

Lolita was one of several seers that Carmen promoted among friends and relatives. At Ezkioga Starkie met Medina's elderly cousin, the duke of T'serclaes. The duke was a fixture of the San Sebastián summer set and Mateo Múgica used to stay in his house on the Calle Serrano on his trips to Madrid. Carmen's sister María, the duchess of Tárifa, went to pray for her husband, and one seer, after consulting the Virgin, assured the duchess that he would recover. A sister-in-law, the countess of Campo Rey, was at Ezkioga in December.[40]

S 130; Moreda, "Mateo Múgica," 222; L 10; R 56, 4 December 1931.

María Dolores Núñez, 12 July 1931, the night of her

first vision. From El Pueblo Vasco, 14 July 1931.

Courtesy Hemeroteca Municipal, San Sebastian

Carmen is almost certainly the grand dame a visitor described in early August as "the confidante of the most interesting seers" who assured visitors that the great miracle would come soon. She took particular interest in two seers from Ataun, both of whom learned "secrets" from the Virgin and claimed knowledge of the timing and content of the upcoming miracle.[41]

Lassalle, PN, 9 August 1931.

Ramona's Friend, the Girl from Ataun

By early October a girl seer, age eighteen, from Ataun had become inseparable from Ramona. Like Ramona, she too was from a farm and had worked as servant

to a prominent family in Ordizia. Her hands were those of señorita, and there is a photograph of her sitting at a Singer sewing machine. Her visions had started on July 12, four days before those of Ramona. They were quite detailed and received wide publicity. The Virgin first spoke to her, she said, on July 16. At the end of the month she was seeing the Virgin several times daily.[42]

Picavea, PV, 6 and 11 November 1931; ED, 17, 26, and 29 July 1931; PN, 22 July 1931.

In August she gave a special blessing from the Virgin to a Catalan cleric who had singled her out of the mass of seers. She claimed to have a vision every time she went to the hillside; by September 27 she had had them on forty-one days. Like Ramona she was conspicuously good-natured and felt no call to the cloisters.[43]

Elías, CC, 19 August 1931; Farre, EM, 8 October 1931; Cardús to Rafael García Cascón, 13 October 1931; PV, 20 October 1931.

This girl, Ramona, and an unnamed Tolosa seer helped one another when in trance. They stayed together on the morning of October 15. When Ramona's hands started to bleed, the Ataun girl was probably the seer who announced to the crowd, "The Virgin has cut her with swords and now places a rosary around her waist!" The next morning as the public pressed to kiss Ramona's hands, she, the Tolosa seer, and Ramona talked to reporters together.[44]

Detailed accounts of events on October 15 in Easo, 16 October 1931; and in my interview with Pío Montoya, San Sebastián, 7 April 1983, p. 7.

At that time a family from Bilbao was pampering both the Ataun girl and Ramona. Julio de Lecue was a stockbroker and his brother José was a painter and sculptor. They had nieces the age of Ramona and her friend. José in particular was close to Ramona, and in mid-October she began to dictate to him what she saw in her visions.[45]

R 60; PV, 17 October 1931.

On the morning of Ramona's miracle José de Lecue refused to leave her side, which prevented an effective search by the Aliadas. He was one of the two men who carried Ramona down the hill in a chair. On the days after the miracle some reporters briefly suspected him of having made the wounds on her hands. Another suspect was a confidence man and pickpocket who had allegedly boasted how he could arrange a miracle at Ezkioga.[46]The pickpocket was Isidoro Arpón Jaime; suspicious reporter: Juan de Urumea, in PV, 20 and 21 October 1931, p. 2, and in El Nervión, 22 and 23 October 1931.

On October 16 after the diocesan inquiry into Ramona's wounds, attention shifted to the girl from Ataun. Over sixty thousand persons had gathered on the hillside, and for the first time the seers used a stage Patxi Goicoechea had been building with lumber and manpower from the owner of the land. Only family members, priests, and reporters could go with the seers on the stage. The seers lined up in late afternoon, and many fell into trance. A medal of the Daughters of Mary on a blue ribbon appeared in the Ataun girl's hands, as if out of nowhere, and shortly thereafter another appeared in the hands of a seven-year-old girl from Ormaiztegi.[47]

SC E 94-97, 101-104; LC, PV, Easo, and DN, 17 October 1931.

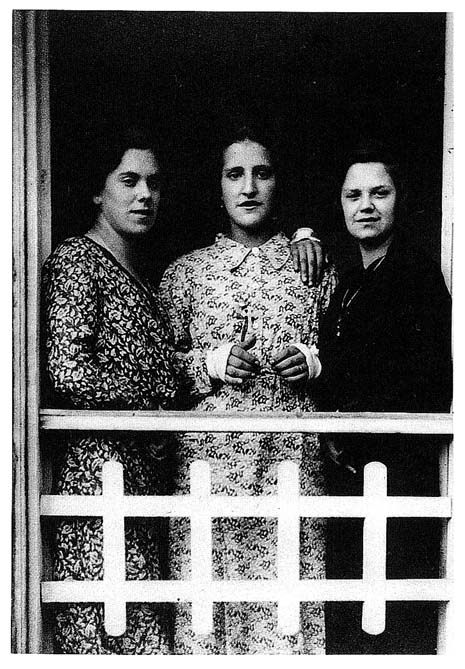

On Saturday, October 17, yet more people came, most of them unaware of the vicar general's finding about Ramona. The Ataun girl suddenly lifted one of her hands, which had a little scratch, and said that the Baby Jesus had left the mark with a dagger. We see her the next day in a proud pose with Ramona, both of them discreetly displaying their bandages from a window of the fonda. Shortly after this high point, Carmen Medina began to look after the Ataun girl.[48]

Teresa Michelena, Oiartzun, 28 March 1983; SC E 101-106, 169; Castellano, PV, 20 October 1931; Rigné photography of crowd, plates 33, 261, 262, collection of author; PV and LC, 18 and 20 October 1931; Easo, 19 October 1931; for Medina's interest in the Ataun girl see L 14.

Ramona Olazábal and the girl from Ataun, 18 October

1931. Photo by Raymond de Rigné, all rights reserved

Francisco (Patxi) Goicoechea, the Convert

Carmen Medina also took an interest in Francisco Goicoechea, known as Patxi or "the lad from Ataun." At the end of July Medina told Starkie that Patxi (pronounced Patchi) had become a veritable Saint John of the Cross in his piety. His parents were tenant farmers and he was a carpenter on construction jobs. His first vision occurred on 7 July 1931, as he was making fun of the visions of others. His deep trances became a highlight of the vision evenings. Stern young men from Ataun generally went with him; they would carry him semiconscious down to the recovery room. He became the central figure in the apparitions from early July and was, in the words of the industrialist and deputy Rafael Picavea, "the most famous youth in the entire region."[49]

S 130; Picavea, PV, 13 November 1931. Except for the two-day parenthesis of Ramona's wounds, the press treated Patxi as the central figure from late July to mid-November.

We have seen that it was Patxi, a Basque Nationalist, who came out and said that the Virgin called for the overthrow of the Republic. He took the initiative in other ways as well. He put up a wooden cross at the site in August, the stage in October, and stations of the cross the following February. Patxi repeatedly predicted miracles, including ones for July 16 and mid-October. The Ataun girl and Evarista Galdós from Gabiria normally supported him.[50]

Construction, ARB 19-21; miracle predictions, ED, 23 July 1931, p. 8; SC E 13; García Cascón to Francisco de Paula Vallet, 31 October 1931, AHCPCR 10-A-27/2; Picavea, PV, 6 and 8 November 1931.

Patxi made a large and varied number of friends. He allegedly had the use of the automobiles of a devout Bilbao heiress, Pilar Arratia, and the Traditionalist physician Benigno Oreja Elósegui, brother of a deputy in the Cortes.[51]

L 14. Arratia gave 3,000 pesetas to the seminary fund in 1931 (BOOV, 1931, p. 354) and provided a house for the Ave Maria schools in Bilbao whose director, Doroteo Irízar, was also an Ezkioga sympathizer. She visited the German mystic Thérèse Neumann in the winter of 1931-1932. María Recalde had a vision in Bilbao at the house of "P. A.," 18 January 1932, allegedly in the presence of the brother of Cardinal Segura, B 601-602.

Because of his prestige, believers took him to observe the visions of little girls in the riverbed by Ormaiztegi, which he judged diabolical, and those of children in Navarra. Carmen Medina took him to Toledo at the beginning of October so he could attend the visions of children in the village of Guadamur.[52]Ormaiztegi (August 31): Easo, 17 October 1931. Navarra (Bakaiku): Picavea, PV, 6 November 1931. Guadamur: Cardús to García Cascón, 5 October 1931, and Picavea above. Patxi traveled to Bilbao, SC E 111, and in 1933 observed Luis Irurzun in Iraneta (Navarra), according to Pedro Balda, Alkotz, 8 April 1983, pp. 21-22.

By November Patxi had tried to pass on divine messages to the Basque deputies Jesús Leizaola, Marcelino Oreja, and José Antonio Aguirre. When he heard that Patxi had a message for him, Leizaola replied, "Message from the Virgin? I know her too. If she has something important she wants me to know, she will give it to me herself." In early December it had become clear that the vicar general of Vitoria rejected all the Ezkioga visions, and Patxi, Carmen Medina, and the other believers could only hope that the exiled bishop felt differently. Rumor had it that on December 14 Patxi had given Bishop Mateo Múgica, by then in the village of La Puye near Poitiers, a sealed letter that said the miracle would take place on December 26.[53]

On deputies, Picavea, PV, 8 November 1931; on rumored trip to France, J. R. Echezarreta to Cardús SC E 249, and Clotilde Moreno Eguiguren to a correspondent at Ezkioga, Bilbao, 15 January 1932.

I am not certain that Patxi went to France, but in any case he passed on the Virgin's instructions for Carmen Medina to take a group of seers to see the bishop. Medina went with Ramona Olazábel, the girl from Ataun, the child Benita Aguirre, Evarista Galdós, and a fifth seer on December 19. Bishop Múgica spoke to each seer separately for half an hour and allegedly told Carmen Medina that, whatever the origin of the visions, he did not think the seers were knowingly lying.[54]

ARB 44; R 29; B 290, 320, 717; Múgica, "Declarando," 242, 244; Echezarreta to Cardús, 24 December 1931 (SC E 263-264), and 7 January 1932. Declaration by Ramona to Rodríguez Dranguet, 18 November 1932, from private archive. Sources give the fifth seer as Juana Ibarguren of Azpeitia or María Luisa of Zaldibia.

Francisco Goicoechea (second from left) and friends at Ataun,

October 1931. Photo by Raymond de Rigné, all rights reserved

For the people of Ataun Goicoechea was "Patxi Santu [Holy Patxi]." They remember lines of cars parked in front of his farm and people kissing his hand and leaving presents. The nickname probably came after his apotheosis on 1 August 1931, when newspapers reported that he had levitated. After that he received large numbers of letters. In the summer of 1931 or 1932 Carmen Medina organized a bus excursion to Ezkioga for her many nieces and nephews living or vacationing in San Sebastian; they also went to Ataun, where Patxi obligingly entered into a trance. When they asked what the Virgin had said, one of Patxi's friends said she wanted them to leave the bus in Ataun for the use of the village.[55]

For levitations see chap. 10 below, "The Vision States"; correspondence, Rodríguez Ramos, Yo sé, 15; bus excursions, Rafael Medina y Vilallonga, Sevilla, 23 October 1989.

Patxi was a complex individual, and those who knew him offer conflicting testimony. Some say he drank a lot; others say he did not. They agree that he attended church, both before and after the visions, and that for a while during the visions he went to church daily. He was tall and handsome and spoke Basque better than Spanish. With some reporters he was camera shy and defensive, especially when there were questions that implied his vision state might have a component of mental illness or epilepsy. Some remember him as messianic. In the

projected reconquest of Spain, they recall, he was going to be the captain. Like some of the other more dramatic seers, he asked to die for his sins to save the world: "Mother, mother, do not weep, kill me, but forgive the rest, for they know not what they do."[56]

Lassalle, PN, 9 August 1931.

Patxi had his cuadrilla, a friend who answered his mail, and a schoolteacher who took down his messages. He also had the support of priests, at first from his parish, then from elsewhere. Therefore he did not need the kind of patronage that the younger or poorer seers did. From the end of August 1931 and continuing through early 1933 at least, he usually went to Ezkioga on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday nights with his friends. By the beginning of 1932 he was no longer the center of attention, and by May 1933 his nocturnal visions were almost furtive, his small band quite separate from the daytime seers. Formerly he arrived in a chauffeured car; now he came and went on bicycle after work.[57]

García Cascó to family in Bejar, September 1931, in García Cascón, "Algo más"; Picavea, PV, 3 November 1931; Ducrot, VU, 30 August 1933, p. 1365.

I do not know whether the subsequent absence of news about Patxi was the result of his rejection by others or his own self-exclusion. Perhaps the Carlist-Integrist believers, who predominated after 1931, rejected him for his nationalism. Or perhaps he was burned by bad publicity. His public downfall began with that of Ramona. As Catholic newspapers began to feel freer to print negative information, they pointed out that Patxi had made many false predictions. Rafael Picavea in El Pueblo Vasco exposed Patxi's inconsistencies. And when Patxi protested, Picavea ridiculed him for social climbing with Carmen Medina. As Patxi, Ramona, and the girl from Ataun fell from grace, the other seers also began to turn on them. Benita Aguirre reported that the Virgin had told her that the decline of a seer named F (almost certainly Patxi) should be an object lesson for seers, that they should shun worldly honors: "They spoiled him, and now what is left for him?"[58]

Goicoechea, ED, 12 November 1931; Picavea, PV, 13 November 1931; vision of Benita Aguirre, date not given, B 568.

The diocese early identified Patxi as a troublemaker. In August 1931 he refused to remove the cross he had put up on the hillside. And on December 26 Bishop Múgica of Vitoria sent his fiscal, or magistrate, to take testimony in Ormaiztegi that Patxi predicted a miracle for that day. Patxi had convinced Carmen Medina, who had imprudently spread the word. Patxi lost further credibility when he predicted a miracle for January. His clerical support in Ataun dropped away. He probably made his nocturnal visits to Ezkioga in late 1932 and 1933 in spite of explicit, personal diocesan orders not to go. Like most prominent seers, he also had trouble with the Republic, and in October 1932 the governor sent him for observation to the Mondragón mental hospital.[59]

For prophecy and investigation: Cardús to Ramona, 16 and 30 December 1931; Múgica, "Declarando," 241; and R 41-42. For Patxi in Mondragón: Burguera to Cardús, 22 October 1931; B 380; ARB 163; R 32-33. He was released 13 November 1932.

We catch a final glimpse of Patxi's complexity when on 15 March 1935 he appeared as a witness in a traffic case in San Sebastián. There reporters learned that the government had indicted him for taking part in the October 1934 uprising. Socialists had led the rebellion and took over much of the province of Asturias. In the Basque Country the more radical nationalists participated by trying to organize a general strike. When a reporter asked Patxi about his

involvement in the rebellion, he complained, "If I had known that they brought me here to bother me with questions about my private life, I would not have come. Whose business is it that I am the fellow involved with Ezquioga and at the same time an advanced republican?"[60]

Gil Bare, PV, 16 March 1935. For 1934 uprising see Fusi, "Nacionalismo y revolución," and Granja, Nacionalismo, 491-505.

I do not know how Carmen Medina's friendship with Patxi ended. Surely his crossover from the revolutionary right to the revolutionary left would have alienated her had they maintained contact. Her family remembers that Carmen dropped one youthful male seer when he told her that he and she should get married, by order of the Virgin.

Evarista Galdós

A final seer in whom Carmen Medina took special interest was Evarista Galdós y Eguiguren. Evarista was seventeen years old when she began to have visions in early July 1931. She came from a farm in Gabiria, not far from the vision site, and when the visions started she was in service in the home of a journalist in San Sebastián. The press described her visions in early July but did not mention her again until the fall. By that time she had had over thirty visions and went to Ezkioga on Thursdays and Sundays, presumably her days off from work.[61]

Her employer, Díaz Alberdi, alleged that she claimed she too would see the Virgin at Ezkioga: Juan de Urumea, El Nervión, 23 October 1931. First visions, ED and PV, 14 and 15 July 1931; also B 32, 714-715; Boué, 23-24. For October 1931 see SC E on 4 October, Rigné photo 261 on 17 October, PV and Easo, 20 October, and LC, 21 October.

The believers heeded Evarista more from mid-October. On October 18 and 19 the Jesuit José Antonio Laburu filmed her and Ramona having visions.[62]

Hermano Rafael Beloqui, Urretxu, 15 August 1982; Easo, 20 October 1931, p. 8; L 10.

On October 19 she told a reporter that both she and Patxi knew when the big miracle would be and that it would be soon: She predicted a miracle for the next day, which attracted a large crowd that was duly disappointed; with the seer girl from Ataun she predicted another for November 1 between 4:00 and 4:15 P.M. On December 4 she claimed to receive from heaven a medal on a ribbon like those others received previously. She announced this event in advance to a sympathetic priest and had herself searched beforehand. By this time she was important enough for Carmen Medina to take her to the bishop in France.[63]R 55; B 717.

On 17 January 1932 Evarista, Ramona, the Ataun seer, and six other girls from the district attended the spiritual exercises offered by the Reparadora nuns in San Sebastián. Carmen Medina may have paid for them. Her family patronized this elite order, whose first house in Spain was in Seville. Carmen's sister Dolores had founded the houses in San Sebastián and Madrid. Antonio Amundarain might have suggested the exercises; he had been the confessor of the Reparadoras in San Sebastián, and the Aliadas went for exercises there. Whoever was responsible probably also had a hand in the spiritual exercises at Loyola for male youths who were seers and converts. The Reparadoras based their rules on those of the Jesuits, and the Jesuits worked closely with them. Like the exercises of the Jesuits, those of the Reparadoras emphasized atonement, in which "a detailed contemplation of the scenes of the Passion … poses the question of acting and

Evarista Galdós with ribbon and medal that on 4 December 1931 fell

to her from the sky. Photo by Raymond de Rigné, all rights reserved

suffering for Christ in return." Immediately subsequent to these exercises Evarista and other seers began to have visions in which they experienced the crucifixion.[64]

For exercises see SC E 278, citing letter from J. R. Echezarreta of 18 January 1932; for Dolores see the anonymous biography Padrón de Superioras, 173-185. Carmen's sister Concepción and a niece were also in the order. On Amundarain see the chronicles in LIS, passim. In Vitoria the Aliadas used the Reparadora house for ceremonies in 1929 and 1931. For Loyola exercises see SC E 278. Amundarain did exercises there in early 1920s: Pérez Ormazábal, Aquel monaguillo, 73-74, 85-86. Quote is from Édouard Glotin, "Réparation," DS 13 (1988), col. 385. Émilie d'Oultremont founded the Reparadoras in Strasbourg in 1857.

In 1932 Evarista and Ramona stayed for a time in Azkoitia in the house of a wealthy woman, who paid a driver to take them back and forth to Ezkioga daily. But the two seers had a bad falling-out. Only the concerted efforts of José de Lecue, the Bilbao artist, and Patxi in a meeting in Bilbao in April led them to make peace. In the fall of 1932 and early 1933 a young male convert recorded Evarista's visions. This friendship cost Evarista some of her more prudish followers. She lived for most of 1933 in Irun. There she convinced a priest after having a vision in his house, and he started taking down her messages. Many of these visions had to do with the adventures of the believing community. She saw specific churchmen conspiring against the visions, other seers having their final visions, the hostile clergy changing their minds and believing, and other mystics making prophecies.[65]

On Evarista's trouble with Ramona see SC E 279, 434-435; on José Atín, the male convert, see Surcouf, L'Intransigeant, 19 November 1932; Rigné to Olaizola, 2 October 1932; Rigné to Ezkioga believer, 29 January 1933. For Evarista in Irun and priest, B 312, 726; García Cascón visited her there 7 December 1933. For community visions, B 714-717.

In January 1934 Carmen Medina spirited Evarista off to Madrid. There Medina hoped to set up a refuge from the coming revolution for a "high dignitary," who was in all likelihood the papal nuncio, Federico Tedeschini.[66]

Ayerbe to Cardús, 18 January 1934. She and Carmen lived at Calle Alfonso XII 32, 3° (López de Lerena to Ezkioga believer, 19 April 1934, private collection). More on Evarista and Tedeschini below in chap. 6, "Suppression by Church and State."

Carmen Medina was in the class of grandees, enjoying powerful ecclesiastical, political, social, and financial connections. She was untouchable, even unmentionable. When the diocesan investigator went to Ormaiztegi to document Patxi's false prediction, his investigation included Medina, but he nonetheless accepted her hospitality and ate with her. The bishop and vicar general had no qualms about attacking other key figures openly, but they steered clear of Medina. Even in private correspondence Ezkioga believers mention her circumspectly. Only a complete outsider, Walter Starkie, could be frank about her.[67]

When Burguera referred to her he often called her C. M.; Picavea wrote obliquely about a "dama aristocrática"; and Laburu even in his private lecture script wrote C. Med., though he spelled out all other names (e.g., L 14).

The most overtly political of the Ezkioga patrons, Carmen Medina needed no one to tell her a civil war was imminent, and she knew which side she was on. Nor did the other patrons have any doubt about their sympathies. But they considered politics a distant second to religion. Amundarain is a case in point: what was foremost for him was the saving of souls and the spiritual mission of his new order in the unfolding divine plan. In the June 1931 issue of Lilium inter Spinas he put politics in its place:

Say it, dear Sisters. Hail Jesus in our hearts and in those of all others as well! Hail Jesus in those who love us and those who persecute us! Hail Jesus in those who rule and those who obey! Hail Jesus in the Republic, in its governments, and its laws! Hail Jesus in the Church, in its ministers, and in its faithful! Hail Jesus in the heavens, on earth, and in the depths! Hail Jesus now and forever, Amen, Amen![68]

Amundarain, LIS 35 (June 1931): 1-11.